An fMRI study on the generalization of motor learning after brain actuated supernumerary robot training

Introduction

Motor learning is one of the crucial abilities throughout human life, enabling the acquisition of new skills or recovery from injuries through practice1. Previous research has also indicated that the acquisition of one skill can facilitate the subsequent learning of new skills, and the attribute related to this phenomenon is generalization. Generalization is defined as the ability to apply what has been learned in one context to other contexts, influenced by training schedule and similarity of skill sequences2. However, current studies on the generalization of motor learning abilities primarily focus on the effects of varying training intensities and intervention times on human limb training performance3,4,5. With the advancement of human-machine interaction technologies6, investigating the generalization of motor learning abilities under collaborative human-machine training presents a worthwhile area for exploration.

Previous research has indicated that human-machine collaborative training yields significant benefits in the field of disease rehabilitation7,8,9. Patients with impaired limb motor function can undergo motor relearning through devices such as electrical stimulation10, mobile robots11, and exoskeletons12, thereby reshaping central motor pathways while achieving functional recovery of limb movement. Additionally, apart from directly stimulating the limbs and their corresponding central nervous system, scientists have also shown considerable interest in novel “brain-limb” interaction approaches13,14,15,16. In the field of surgery, a novel “brain-limb” connection has been established by surgeons through transferring the C7 nerve from the non-paralyzed side of cerebral injury patients to the paralyzed side. Through long-term motor learning, patients regain grip capability in the paralyzed limb, which operates independently from the healthy side13. Polydactyly represents a congenital form of “brain-limb” interaction, where patients exhibit enhanced single-hand grip functionality while establishing a direct “sixth finger” “brain-limb” neural connection, and forming a unique “sixth finger” brain region in the brain14. In the engineering domain, robotics experts have designed novel limb form—supernumerary robotic finger (SRF)—for compensating grasping deficits in hemiplegic patients and enhancing hand grip functionality in able-bodied individuals15,17,18,19. Post-training, the neural representation of the biological five fingers and the sensorimotor network in the brain undergo reorganization15,19,20. However, current control methods for these systems often rely on arm or toe movements15,21, EMG signals18, lacking direct brain-to-SRF mapping connections.

In recent years, with the advancement of brain-computer interface (BCI) technology, significant progress has been made in understanding how the brain adapts to external stimuli and device manipulation22. Visual induction, motor imagery, and similar techniques induce changes in the brain’s physiological electrical signals8,23,24,25. Specifically, motor imagery involving biological limbs activates brain neurons akin to those engaged during actual limb movement26. Building on this understanding, the collection and decoding of brain signals from patients with motor impairments via BCI technology, directly connected to rehabilitation devices, bypasses the normal neural pathways between the brain and biological muscles, facilitating direct control training8,25. By harnessing the independent control advantages of BCIs and linking them with SRF devices, a direct connection between the brain and the SRF in a biomimetic fashion is established. Previous study has also demonstrated that BCI can manipulate supernumerary robotic limb device and has the potential for motor enhancement27.

The study of motor learning involves bilateral sensorimotor networks in the brain, including the sensorimotor cortex, cerebellum, basal ganglia, and thalamus1,28,29,30. Specifically, Toni et al. through task-based fMRI analysis found that motor sequence learning mainly involves activation of the prefrontal and sensorimotor networks like the premotor, parietal cortex and cerebellar areas31. And Rachel Seidler et al. also found that transcranial direct current stimulation of the M1 brain region in the sensorimotor network promotes sequence learning and relearning32. These studies indicate the major role of sensorimotor network in motor sequence learning. Existing neuroplasticity findings in human-machine operation skill learning also predominantly focus on the sensorimotor networks. Specifically, functional connectivity increases between sensorimotor regions have been observed in BCI controlled shoulder-elbow movement machines11, hand exoskeletons12, and wrist stimulation rehabilitation devices10. Moreover, physiological novel “brain-limb” training has also found changes in the activation of the sensory motor cortex13. However, existing research on SRF robots primarily focuses on motor augmentation, yet lacks investigation into the neuroplasticity mechanisms of the brain. Additionally, there is a notable absence of studies addressing the ability of novel skill generalization learning under human-machine interaction skill training driven by brain-actuated SRF.

This study aims to investigate the generalization of motor sequence learning ability and the corresponding neuroplasticity mechanisms under brain-actuated SRF training. We hypothesize that brain-actuated SRF training can enhance the generalization ability of motor sequence learning by enhancing the functional reorganization of sensorimotor network. To test our hypothesis, we constructed a brain-actuated SRF robot system33, proposing a “ six-finger” motor imagery paradigm34 to achieve direct brain control of the SRF. Subsequently, participants were recruited to undergo a 4-week brain-actuated SRF training (BCI-SRF) or inborn finger training group (Finger). Behaviorally, participants underwent daily SRF-Finger training sequences, selecting untrained novel SRF-Finger opposition sequences at pre-, post-training, and follow-up assessments as measures of generalization of motor sequence learning ability. In terms of imaging, we collected task-based (tb-fMRI) and resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) data, focusing on the sensorimotor network, to observe changes of functional connectivity pre- and post-training. Finally, we explored the correlation between behavioral changes and network connectivity changes, thereby elucidating the neuroplasticity mechanisms underlying the enhancement of motor sequence learning ability.

Results

Demographic characteristics

There is no significant difference in demographic characteristics of the participants among 2 groups in age, gender and handedness are shown in Table 1. A brief survey was conducted on BCI-SRF system, and all participants expressed satisfaction with the comfort and safety of the SRF finger.

Results of behavioral analysis

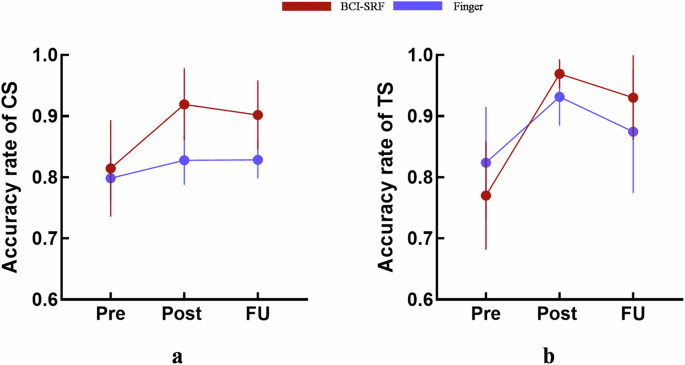

The behavioral assessment with control sequence accuracy rate (CS) and training sequence accuracy rate (TS) in the timepoint of Pre, Post and FU were listed in Table 2. There were no significant differences in the CS (p > 0.99) and TS (p = 0.367) at pre stage among 2 groups (Table 2).

A significant TIME × GROUP interaction effect was found (mixed-design ANOVA, F (2, 34) = 6.318, p = 0.0046) in the CS performance. Significant difference in CS score (Post, p = 0.0016; FU, p = 0.0139) was witnessed at Post and FU among 2 groups in Table 2. Post-hoc tests showed a significant increase after training for the BCI-SRF group (Post vs Pre: p = 0.001, FU vs Pre: p = 0.0182) but not for the finger training group (Post vs Pre: p = 0.0613, FU vs Pre: p = 0.052). In the BCI-SRF group, CS score showed significant improvement from 0.815 ± 0.08 at Pre to 0.919 ± 0.06 at Post, and 0.902 ± 0.07 at FU (p < 0.05). While in the Finger group, CS score remained a slight improvement from 0.799 ± 0.04 at Pre to 0.828 ± 0.04 at Post, and 0.836 ± 0.03 at FU (p > 0.05) without significant changes. BCI-SRF subjects improved by 0.105 ± 0.02 rate [-0.005, 0.182] after training (post vs pre), whereas finger subjects did only by 0.03 ± 0.01 rate [-0.01, 0.1] (Fig. 1a). After calculation, the ratio ({R}_{Delta {CS}}) is 350% which indicated the improvement in novel sequence learning ability before and after BCI-SRF training is 350% times to the improvement in finger training group.

The accuracy rates are reported at Pre, Post and FU points. a The changing trend of control sequence accuracy rate (CS). b The changing trend of training sequence accuracy rate (TS).

In the TS performance, there was also a significant TIME × GROUP interaction effect (mixed-design ANOVA, F (2, 34) = 4.794, p = 0.0147). But there were no significant differences at Post and FU among 2 groups in Table 3 (Post, p = 0.8375; FU, p = 0.3342). Post-hoc tests revealed a significant increase not only for the BCI-SRF group (Post vs Pre: p = 0.0001) but also for the finger training group (Post vs Pre: p = 0.0045). However, improvement in FU vs Pre was found only in the BCI-SRF group (FU vs Pre: p = 0.0003), but not for the finger training group (FU vs Pre: p = 0.418) (Fig. 1b).

Results of tb-fMRI Analysis

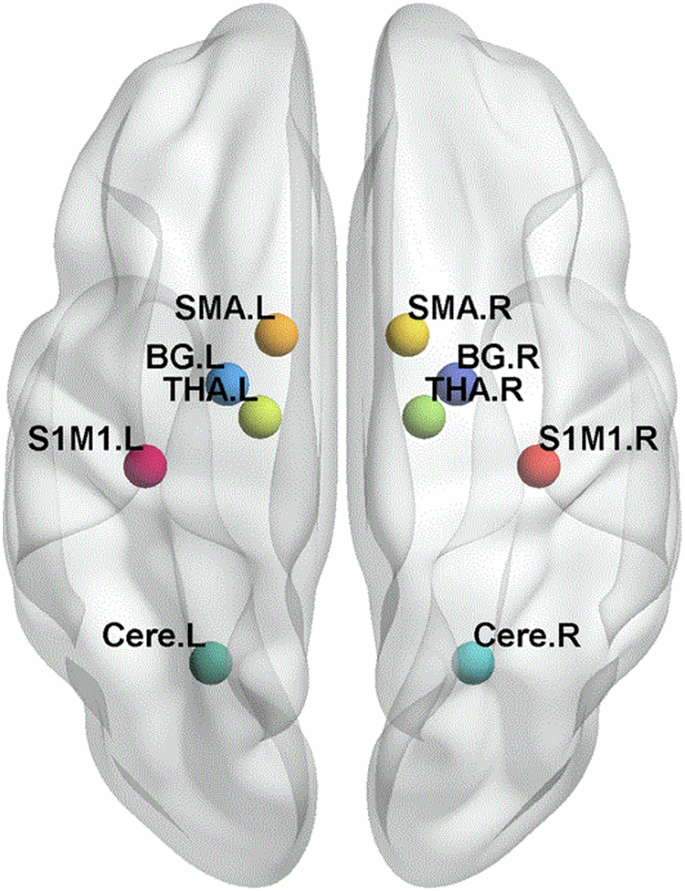

The whole sensorimotor network including S1M1, SMA, thalamus, basal ganglia and cerebellum was screened through tb-fMRI group-level activation (Fig. 2 and Table 4).

The visual depiction of the regions of interest (ROIs) of sensorimotor network after task-based fMRI data analysis. BG, basal ganglia; THA, thalamus; Cere, cerebellum, S1M1, the primary sensorimotor cortex; SMA, the supplementary motor area; L corresponds to the left hemisphere, and the R corresponds to the right hemisphere.

Results of resting-state FC analysis and correlation with the behavior performance

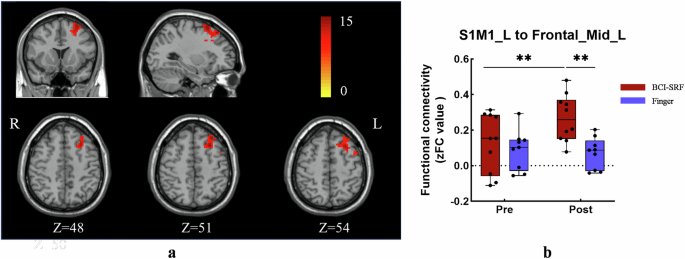

1) Seed-Based Whole-Brain Analysis: The S1M1_L, SMA_L, S1M1_R, SMA_R were set as seed to explore the whole-brain FC at Pre and Post sessions. A significant TIME × GROUP interaction effect was found in the FC between S1M1_L and Frontal_Mid_L (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 1) (F (1, 17) = 10.45, p = 0.0049). Post-hoc tests showed a significant increase after training only for the BCI-SRF group (Post vs Pre: p = 0.0041). Additionally, significant changes were observed at post stage compared in the two groups (p = 0.0014) (Fig. 3b).

Significant increase in FC between S1M1_L and Frontal_Mid_L. a Seed-based whole brain FC found the Frontal_Mid_L was the significant change area when seed was S1M1_L. The color-coded are illustrates the significant clusters of Frontal_Mid_L. b A two-way repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significant increase of FC between S1M1_L and the Frontal_Mid_L for the BCI group (red) as compared to the finger group (light blue). FC: functional connectivity. S1M1: the primary sensorimotor cortex; L corresponds to the left hemisphere, and the R corresponds to the right hemisphere.

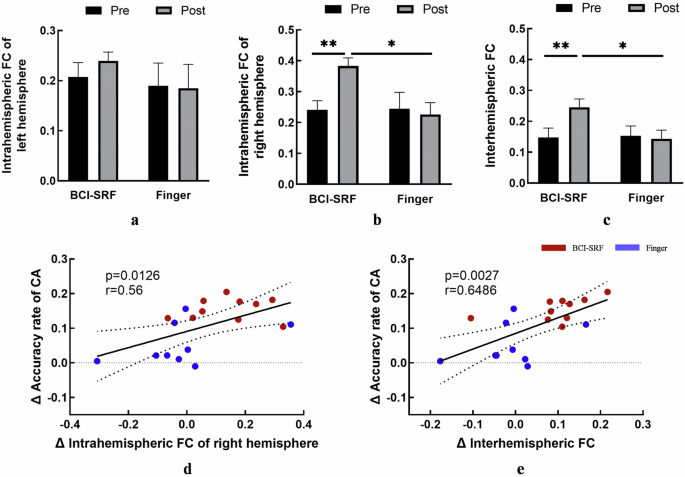

2) FC Changes within Sensorimotor Networks: In the analysis of intrahemispheric FC, the left hemispheric FC had no significant interaction effect (F (1, 17) = 0.2347, p = 0.6342) (Fig. 4a), while the right hemispheric FC showed TIME × GROUP interaction effect (F (1, 17) = 5.452, p = 0.0321). Post-hoc tests showed a significant increase after training only for the BCI-SRF group (Post vs Pre: p = 0.0061). Additionally, significant changes were observed at post stage compared in the two groups (p = 0.0106) (Fig. 4b). Moreover, the interhemispheric FC also showed a significant TIME × GROUP interaction effect (F (1, 17) = 7.395, p = 0.0146). Post-hoc tests showed a significant increase after training only for the BCI-SRF group (Post vs Pre: p = 0.0046). Additionally, significant changes were observed at post stage compared in the two groups (p = 0.0379) (Fig. 4c).

BCI-SRF group exhibited a significant increase in inter- and intra-hemispheric FC of the sensorimotor network, and these increases were significantly correlated with the changes of CS accuracy rate. a Comparison of intrahemispheric FC in the left hemisphere between the BCI-SRF group and the Finger group at pre- and postintervention. b Comparison of intrahemispheric FC in the right hemisphere between the BCI-SRF group and the Finger group at pre- and postintervention. A two-way repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significant change between two groups. c Comparison of interhemispheric FC between the BCI-SRF group and the Finger group at pre- and postintervention. A two-way repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significant change between two groups. d Significant correlation was found between the change of intrahemispheric FC in the right hemisphere and control sequence accuracy rate (CS) change. e Significant correlation was found between the change of interhemispheric FC and control sequence accuracy rate (CS) change. FC: functional connectivity; CA: control sequence accuracy rate; Error bars indicate SD.*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

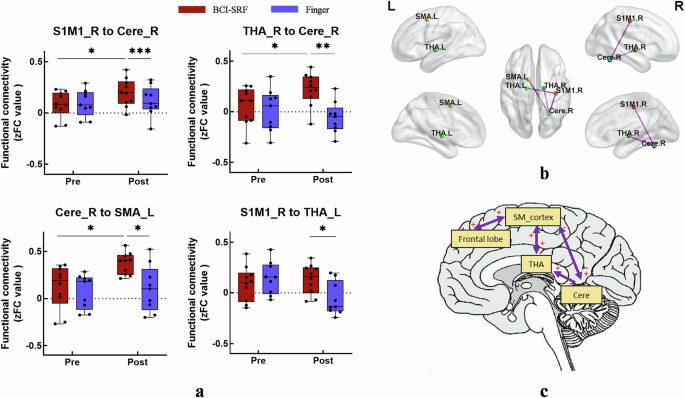

The inter-group comparison of each pair FC within sensorimotor network at pre and post stage were assessed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA. A significant TIME × GROUP interaction effect was found between these 4 connections (S1M1_R with Cere_R: F (1, 17) = 4.527, p = 0.0483; THA_R with Cere_R: F (1, 17) = 4.817, p = 0.0424; Cere_R with SMA_L: F (1, 17) = 4.623, p = 0.0462; S1M1_R with THA_L F (1, 17) = 6.182, p = 0.0236) (Fig. 5a, b). Post-hoc tests showed significant changes at post stage between the two groups in these above connections (p < 0.05). Additionally, a significant post vs pre increase only for the BCI-SRF group in the S1M1_R to Cere_R (p = 0.03), THA_R to Cere_R (p = 0.004), Cere_R to SMA_L (p = 0.012).

The BCI-SRF group showed enhanced FC in the cortical and subcortical brain regions and increased causal effects in the frontal-parietal circuit and the cortical-subcortical circuit. a Comparison of each pair FC between the BCI-SRF group and the Finger group at pre- and postintervention. A significant TIME × GROUP interaction effect was found between these 4 connections. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 see text for results). b The effective connectivity was visualized with the BrainNet Viewer. BG, basal ganglia; Cere, cerebellum; THA, thalamus; S1M1, the primary sensorimotor cortex; SMA, the supplementary motor area. L corresponds to the left hemisphere, and the R corresponds to the right hemisphere. c A model showing the distinct causal connectivity of frontal-parietal (SM_cortex) circuit and the SM_cortex-cerebellar-thalamus cortical-subcortical circuit between the two groups. “+/-” represents BCI-SRF group was significant higher/lower than finger group in causal connectivity, and the arrow indicates the direction of connection. SM_cortex: the integration of S1M1_R and SMA_L; THA: thalamus; Cere: cerebellum; S1M1: the primary sensorimotor cortex; SMA: the supplementary motor area; L corresponds to the left hemisphere, and the R corresponds to the right hemisphere.

3) Correlation Between intra/inter-hemispheric FC Changes and CA Scores: Results showed the correlation was significant for intrahemispheric FC of right hemisphere between pre and post sessions to the changes of CA scores (r = 0.56, p = 0.0126) (Fig. 4d). Moreover, the interhemispheric FC was also showed significant correlation with the changes of CA scores (r = 0.6486, p = 0.0027) (Fig. 4e).

Results of GCA analysis

From the results of functional connectivity analysis, the S1M1_R, SMA_L, THA_L, THA_R, Cere_R and Frontal_Mid_L were selected as the ROIs for GCA analysis. Here, the S1M1_R and SMA_L were integrated into the SM-cortex to explore the causal effect of the cortical with subcortical circuits. Compared with the finger group, the BCI-SRF group showed significant bi-directional increase of causal effect between the SM_cortex with the THA and frontal lobe. (SM_cortex to THA: p = 0.01; THA to SM_cortex: p = 0.023; SM_cortex to Frontal: p = 0.02; Frontal to SM_cortex: p = 0.015). Meanwhile, a significant unidirectional increased causal effect was found from the SM-cortex to the Cere (p = 0.012), from the Cere to the THA (p = 0.027). Furthermore, the Cere to the SM-cortex showed significant decreased causal effect (p = 0.024). It was found that the flow of information across these brain regions was mainly along the SM_cortex-cerebellar-thalamus cortical-subcortical circuit. In addition, the frontal-parietal circuit interaction was also significantly enhanced. (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

We observed generalization to a novel SRF-finger sequence after 4 weeks of BCI-SRF training. Furthermore, compared with finger training group, BCI-SRF training significantly increased intrahemispheric FC of the right hemisphere and the interhemispheric between the two hemispheres. And the increase of FC is significantly related to the improvement of motor sequence learning ability. Moreover, a significant causal effect between SM_cortex-cerebellar-thalamus and frontal-parietal loops was found after GCA analysis. And these results revealed that under longitudinal BCI-SRF training, the improvement of motor sequence learning ability is accompanied by functional integration of sensorimotor network and local circuit specialization. These results also validate our initial hypothesis, indicating that BCI-SRF training enhances the generalization ability of motor sequence learning through functional reorganization of sensorimotor networks.

In terms of motor sequence learning ability, the BCI-SRF training resulted in a statistically significant and lasting improvement in control (novel) sequence accuracy compared with the inborn finger training. We speculate that BCI-SRF system transform weak intervention, such as finger training, into an effective one by strengthening motion control efferent pathway and tactile feedback afferent pathway. This finding opens the door to a variety of functional enhancement ways to combine brain-machine-body in which the active involvement of the brain plays a key role compared with the traditional passive human-machine interaction. Previous study has found that motor learning recruited the cortical-subcortical circuits and activated the sensorimotor regions to improve motor performance1,30. Therefore, we speculate that the intervention of brain-actuated SRF can improve motor learning behavioral performance by affecting the activation and the connectivity of sensorimotor network. This speculation was further confirmed in subsequent imaging analysis. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the accuracy rate of the CS showed a slight decrease during the follow-up period after BCI-SRF training, similar to the trend observed in the finger training group (Fig. 1a). This suggests a natural decline in skill retention over time35. Previous research on cognitive and motor skill learning indicates that regular reinforcement training is effective in consolidating and preserving learned skills, thereby sustaining optimal performance levels36. Therefore, we speculate that periodic reinforcement training after BCI-SRF training may alleviate the observed performance decline and maintain the improvement in motor sequence learning ability. Motor sequence learning involves the functional integration of brain’s sensorimotor network1,37,38. The global activation of sensorimotor networks underlies the occurrence of muscle movements and behaviors28,29,39,40,41,42. This study also determined the coordinates of the cortical (S1M1 and SMA) and subcortical (thalamus, cerebellum and basal ganglia) sensorimotor networks through task-state fMRI activation. Specifically, the sensorimotor cortex is connected to muscles through the corticospinal tract (CST) and is responsible for movement planning and coordination. Humans wearing the SRF will rapidly reshaped the CST output pattern and quickly encoded the new SRF morphology into the user’s body schema19, thereby updating the limb’s movement path planning and coordinating the limb’s movement pattern. Therefore, the use of BCI-SRF increases the conduction of efferent and afferent sensorimotor nerve information, thereby increasing activation of cortical and subcortical areas.

Compared with the finger training, the BCI-SRF training showed a significant increased FC in frontal cortex and the S1M1_L. Furthermore, a significant bi-directional increase of causal effect between the SM_cortex and the frontal lobe after GCA analysis indicated the enhanced interaction between the frontal-parietal network. The frontal lobe, as the part of largest volume change in brain evolve from primate to human, plays a key role in the coordination and execution of motor movements via its involvement in cognitive control, goal-oriented behaviors and working memory43,44. Furthermore, direct anatomical connections between the frontal-parietal network further demonstrated the integrated function of high-level cognitive behavioral control and motor performance45. In this study, we speculate that the SRF, as a novel additional limb morphology, will recruit additional cognitive resources from the frontal lobe to complete the goal-oriented coordination task of SRF and innate fingers. This speculation is also consistent with the results of our previous research on the sixth finger motor imagery. Specifically, the event-related desynchronization (ERD) phenomenon in the frontal lobe of the brain was found only in the sixth finger motor imagery rather than the innate limbs, indicating that the frontal lobe specific activation34. The increase in frontal-parietal area functional connectivity further proves that BCI-SRF training will induce broader functional reorganization, thereby improving motor learning performance.

It was interesting to note that the increase in FC occurs not only within the intrahemispheric regions but also in the interhemispheric regions, and this increase is significantly correlated with the improvement in behavioral performance. Previous studies has shown that increased FC in multiple cortical regions is critical for the acquisition of BCI skills46. Clinical studies have also proven that the increase FC in intra-hemispheric47 and inter-hemispheric48 is closely related to better motor function recovery. Therefore, we can reasonably predict that BCI-SRF training will increase the connection between the two hemispheres and make the brain a closer whole, thereby improving the performance of motor learning. It is worth noting that the cerebellum, as an important area of the sensorimotor network, shows a significant in functional connectivity increase with SMA_L, S1M1_R and THA_R, and this increase is not only reflected in the comparison of two group at post stage but also showed before and after training in the SRF group. The cerebellum exhibits supervisory learning function which guided by error signals from the inferior olive. When errors occur during motor learning, it corrects errors by forming a network with the thalamus and cortex49. In this study, the SRF did not reach the trigger threshold of BCI and therefore did not move, which can be used as a kind of error feedback to gradually strengthen the supervised learning function of the cerebellum and continuously repair the learning process by enhancing the activation and cortical connections of the cerebellum. This is consistent with the finding of the specific activation of the cerebellum in our pilot study50. Although we cannot provide further direct evidence of structural plasticity effects, functional plasticity has been proved to be associated with cortical neuro reorganization51. This triggered us to further explore the reorganization of cortical-subcortical circuits in sensorimotor network.

Most notably, the SM_cortex-cerebellar-thalamus network loop exhibited a significant causal effect. Previous research on motor skill learning has identified that different cortical-subcortical network loops, such as the cortical-basal ganglia–thalamus and cortical-cerebellar–thalamus networks, not only employ distinct strategies to enhance learning performance30 but also participate in various stages of the learning process52. Importantly, the interactions of the SM_cortex-cerebellar-thalamus exhibited directed effects. Jaime et al. found the interaction from the cortex to the cerebellum was found to be linked with the supervised (false) learning53. The directional interaction from the cerebellum to the thalamic nucleus can affect the speed of sequence learning49. Furthermore, the directional interaction from the thalamus and cortex is essential for recalling of stored motor representations1,54. Consequently, we speculate that during BCI-SRF training, the directional interaction from the cortex to the cerebellum facilitates supervised learning of motor sequence, the interaction from the cerebellum to the thalamus enhances learning speed, and the interaction from the thalamus to the cortex supports to store and recall motor learning memory. While we believe that the effects of these neural circuits may occur simultaneously and contribute to the learning of human-machine interaction skills, our data are insufficient to elucidate the exact role of each effect or their combination. Furthermore, clinical studies have also found that the causal interaction between cortical and subcortical brain regions is weakened in stroke patients compared to healthy subjects55. Therefore, we speculate that enhancing sensorimotor network loop causal interaction through BCI-SRF training will have a certain effect on rehabilitation for stroke patients.

It is worth noting that the thalamus not only receives projection from cerebellum and integrates information into the cerebral cortex, but also receives further regulation from the cortex. A reasonable explanation for this result is the impact of BCI-SRF training on CST projection enhancement. The CST runs through the entire nerve conduction process from the cortex to the subcortical spinal muscles, and is an important neural transmission circuit for human motion generation and sensory feedback49. The BCI-SRF system includes the SRF motion efferent pathway and sensory feedback afferent pathway, which are synchronously mapped with the CST efferent and afferent pathways, thereby enhancing the aggregation of sensory motor information in the thalamus. The Hebb-like plasticity was amplified through the synchronous activation of the brain sensorimotor areas and peripheral effectors56. Furthermore, tactile cues rely more on the extensive integration of motor memory57. Although we believe that all circuits and projection mechanisms may occur together and contribute to the enhancement of motor learning abilities, our data is insufficient to clarify the exact role of each effect or their combination.

Three properties may explain why our BCI-SRF training produces greater behavioral and neural changes than innate finger training alone. First, the novel limb morphology of hand wearing the SRF will activate the broader neural resources of sensorimotor networks. Second, the efferent and afferent neural pathways of EEG decoding and FES sensory feedback increase CST projections, thereby further enhancing the interaction of cortical-subcortical sensorimotor circuits and improving motor performance. Third, the novel limb morphology and sixth-finger motor imagery paradigms recruit additional frontal resources of the brain. We believe that all three of these characteristics may cooccur and contribute to the ability enhancement of motor learning.

There are a few possible limitations that should be noted. Firstly, the sample size was not very large. Although we collected longitudinal multimodal data with multiple time points, and conducted joint analysis on the multimodal data. But in the future, it is still necessary to recruit more participants to comprehensive understand of the long-term benefits of BCI-SRF training and generalizability. Secondly, the impact of sequence difficulty and sequence length on ability of learning remains to be addressed in future experiments. Thirdly, the sustainability of motor sequence learning ability needs further investigation. Future research should explore the optimal frequency and duration of reinforcement training to maximize the retention and efficacy of BCI-SRF interventions. Fourthly, collecting behavior and MRI data at daily or more time points to further reveal longitudinal changes is valuable. Another limitation of our study, although not critical, is that clinical patients should be recruited to verify the motor relearning and clinical rehabilitation effect of this system in future, considering the potential of clinical application for grasp assist exhibited by the BCI-SRF system.

In conclusion, our results suggest that BCI-SRF training significantly modulates the global integration of sensorimotor networks and the specialization of local circuits, and is accompanied by the improvement of the motor sequence learning ability. This brain-machine-body training may have good potential for motor augmentation and clinical rehabilitation.

Methods

Participants

Twenty subjects with right-handed assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness questionnaire were recruited from Tianjin University. The recruited participants were randomly assigned to the BCI-SRF training group (BCI-SRF) and inborn finger training group (Finger) and gave informed consent. Behavioral and MRI data were acquired for all subjects before (Pre), immediately after (Post) and 1 months after the intervention (FU) respectively. This study was approved by the Tianjin University Human Research Ethics Committee (TJUE-2022-187). One subject in Finger group was excluded from the final analysis due to the scheduling issues after one week of training.

SRF system and intervention protocols

For the BCI-SRF training group, subjects were asked to wear the SRF on the left hand and then imagined the MI paradigm until the system was triggered. Then the SRF finger module will bend four times to complete SRF-finger training sequence task in the order of little-middle-ring-index. For the finger training group, subjects were asked to bend their inborn innate four fingers in the same order of left hand to complete finger bending sequence task. The bending frequency is synchronized with the BCI-SRF group and the training intensity was also taken as the average number of the SRF-finger opposition numbers per week to ensure the generally consistent.

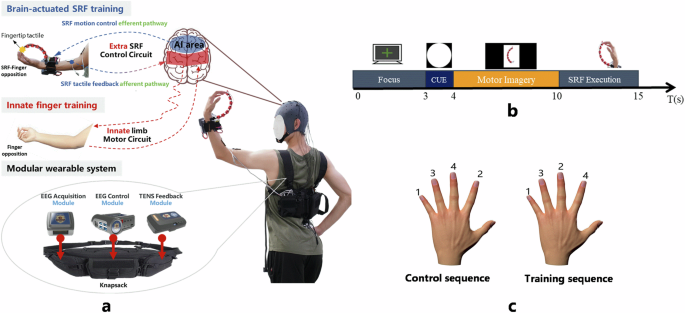

The SRF is a three-dimensionally (3D) printed robotic finger, originally designed to enhance manipulative ability for able-bodied people or supplement the patient’s grasping ability (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Fig. 1). The SRF finger module is worn on the wrist, opposite to the innate middle finger. The control of flexion and extension degrees of freedom is achieved through a single motor drive. The motor is mounted on the human-robot interaction base and powered by an external battery pack worn on the SRF control module. The movement of the SRF finger module is controlled by the brain signal. The EEG signal of “sixth-finger” motor imagery is collected through the EEG acquisition module. This SRF hardware system33 and motor imagination paradigm34 have been reported in our previous article.

The working principle and display of BCI-SRF after wearing, as well as the motor imaginary guidance interface and training and control sequence during the testing phase. a The composition of the wearable hardware system of the BCI-actuated supernumerary robotic finger (SRF). The brain-actuated SRF motion control efferent pathway and the SRF tactile sensory afferent pathway form an extra SRF control circuit. Furthermore, innate limb motor circuit for the finger movement was also displayed. Both circuits are schematic and do not represent actual neurotransmission pathways. (The person gave permission for the use of his image). b The sequence of motor imagery paradigm. c The display of the behavioral measure paradigm.

A wearable signal acquisition system (OPENBCI) is integrated into the EEG acquisition module, which contain 8 electrodes like FC1, FC2, FCZ, etc, covering the motor related areas of both hemispheres and the central region of the brain. Moreover, the Pz was used as the reference and Fpz was grounded. The sampling frequency is 250 Hz. The impedance of each electrode is kept below 5 K Ω by properly filling conductive gel. The 8-13 Hz bandpass filter and 50 Hz notch filer were utilized to remove artifacts and power line noise. The subsequent processing of EEG data includes re-referencing, independent component analysis, and extraction of time-frequency features. Finally, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are used to obtain training models for preprocessed EEG signals, which are used to recognize the dual feature classification states of MI and resting states. The CNN network consists of convolutional layers and fully connected layers. The first convolution kernel has a size of (10,1), aiming to extract the temporal features of EEG signals in each channel and frequency band. The second convolution kernel has a size of (1,8), aiming to integrate the features of 8 channels, extract signal spatial features. Finally, two fully connected layers were used to train a two-feature classification model for resting and MI states.

After being processed by the EEG control module, the control signal is sent to the SRF control module to drive the movement of the SRF finger module to form the control efferent pathway. As the SRF interacts with the natural finger, the capacitive sensor of the SRF fingertip is triggered and the TENS feedback module is driven to send an electrical stimulation feedback signal to the median nerve, forming the sensory afferent pathway. The brain-actuated control efferent pathway and the sensory afferent pathway form an extra SRF control circuit. The time delay of the system is 100 ms.

Both groups received 20 training sessions over 4 weeks, each lasting 60 minutes, excluding preparation and equipment settings. Participants are required to sit at a table during the training process. In the preparation phase of BCI-SRF group, 4 trials were collected and the EEG model was calibrated in about 20 minutes to generate the classifier. During each training trail, the subjects were asked to stare at the cross and relax for 3 s, and then there were 1 s picture prompt for motor imagery. And then the subjects performed motor imagery accompanied by a 6 s video guidance of the SRF bending (Fig. 6b). When the SRF is triggered, the subjects will have 5 s to complete the training sequence in the order of little-middle-ring-index through SRF and finger interaction. In addition, control sequence with the order of little-index-ring-middle was only acquired during data collection to investigate whether training will have any spillover effects on the novel sequence (Fig. 6c). This method has been used in other finger training tasks58.

Behavioral performance

At the Pre, Post and FU period, subjects were asked to wear the SRF on their left hand to perform SRF-finger opposition sequence (training or control sequence) task. And the testing environment was kept consistent with the training environment. Before each sequence testing, two or three sequence of time was given the participants to familiarize the task. Subsequently, the subjects followed the paradigm prompts to perform task as quickly and accurately as possible within 30 seconds. During this time, the number of SRF-Finger opposition was recorded using a handheld camera. In the offline calculation stage, one correct opposition number was counted when the subjects successfully completed once specified sequence. Subsequently, the correct and total opposition number was counted respectively, and used to calculate the control sequence accuracy rate (CS) and the training sequence accuracy rate (TS) by dividing the correct number by the total number, as shown in Eq. (1). Subsequently, as shown in Eq. (2), the improvement in accuracy ((Delta {CS}/Delta {TS})) before and after training for each group will be calculated. Finally, the ratio (({{rm{R}}}_{Delta {rm{CS}}/{rm{TS}}})) of the two groups of accuracy improvements will be calculated, as shown in Eq. (3). Taking the CS as an example, the specific calculation equation is as follows:

Here, N represents the number of control sequence; CS is the accuracy rate of the control sequence; ΔCS represents the CS improvement before and after training; ({R}_{Delta {CS}}) is the ratio of the CS improvement in the BCI-SRF group to the CS improvement of the finger training group.

MRI data acquisition

The MRI data of 19 subjects were acquired at Pre and Post period using a 3 T Siemens MAGNETOM Skyra scanner at Tianjin Huanhu Hospital (Department of Neurosurgery, Tianjin, China). The bold fMRI images (TR/TE = 2000/30 ms, flip angle = 90◦, slice thickness = 3 mm, voxel size = 3.5 × 3.5 × 4 mm3) were acquired gradient-echo planner imaging (EPI) sequence. The T1-weighted structural image was acquired for each participant using the MPRAGE sequence (TR/TE = 2000/2.98 ms, flip angle = 9◦, slice thickness = 1 mm, voxel size 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, acquisition time = 4:26 min).

During tb-fMRI acquisition, subjects were asked to wear the curved SRF finger module on their left hand and move their finger to perform the trained or control sequence with the visual guidance of the screen in blocks of 16 s for task followed by 16 s of rest (Supplementary Fig. 2). A visual display showed a “+” command in rest blocks and the red (train) or blue (control) hand visual cue showed in task blocks to notify subjects performing the training or the control sequence. These visual cues were displayed for 2 s. Four trained-sequence blocks and four control-sequence blocks were randomized and combined with seven rest blocks in each run. And the scan order was maintained consistent among participants. During the rs-fMRI data scanning, subjects keep their eyes closed to stay still and without falling asleep. The rs-fMRI acquisition lasted for 8.06 minutes.

Functional MRI analysis

1) Preprocessing: The SPM12 and RestPlus toolbox were used to preprocess for tb-fMRI and rs-fMRI data59. The preprocessing process60,61,62 of the rs-fMRI includes (1) removing the first 10 time points to make the longitudinal magnetization reach steady state and to let the participant get used to the scanning environment63, (2) slice timing to correct the differences in image acquisition time between slices, (3) head motion correction (4) spatial normalization to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space via the deformation fields derived from tissue segmentation of structural images (resampling voxel size = 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm), (5) spatial smoothing with an isotropic Gaussian kernel with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 6 mm, (6) removing linear trend of the time course, (7) regressing out the head motion effect (using Friston 24 parameter) from the fMRI data[28], and (8) band-pass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz). One participant was excluded from further analysis due to large head motion64 (more than 3.0 mm of maximal translation in any direction of x, y, or z or 3.0◦ of maximal rotation throughout the course of scanning).

The tb-fMRI data preprocessing steps were similar to rs-fMRI. Functional data volumes were slice-time corrected and realigned to the first volume. The mean image of the resultant time series was co-registered with the participant’s temporally-unbiased T1 template. The time series was then normalized into MNI space, an MNI brain mask was applied, and the result smoothed with a 6 mm FWHM isotropic Gaussian kernel.

2) Task-based fMRI Analysis: The tb-fMRI data were analyzed at two levels. For the subject level analysis, the GLM model was used for preprocessing data fitting, and the canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF) was used for convolution of each event and used as a regression factor. After subject level statistical analyses, a t-map for each subject was acquired at each session. For group level analysis, the statistical maps (move > rest) from both groups at pre stage were used to do one-sample t-test. Multiple comparisons were corrected using Gaussian random field theory (voxel p < 0.001, cluster p < 0.05). Then the seed points major regions of the sensorimotor network were screened out, including S1M1, SMA, thalamus, basal ganglia and cerebellum. Furthermore, through the symmetry of the X-axis to obtain the whole sensorimotor network coordinates.

3) Resting-state fMRI Analysis: Two stages of analysis were using for the resting-state fMRI analysis. For the first level, we explored the seed-based whole-brain functional connectivity with 4 seeds on the sensorimotor cortical areas, including S1M1_L, SMA_L, S1M1_R, SMA_R. Then the seeds were defined a spherical ball with a radius of 5 mm according to the coordinate of tasked-based fMRI and calculate the FC with every other voxel in the brain using the average time course of the BOLD signal within this seed.

At the second level analysis, we explore the FC within the entire sensorimotor network which determined by tb-fMRI data65. A 5 mm spherical ball was also defined for each seed in MNI standard space. And the average time course of each seed was used to calculate Pearson correlation coefficient with others. And then Fisher r-to-z transformation used to increase the normality to this coefficient. One 10×10 matrix was acquired for all subjects. Then we compared the differences between the two groups for each pair of FC.

Next, we compared differences in FC of inter- and intra- hemispheres. The interhemispheric FC was defined as the average of FC between each pair of interhemispheric regions while intrahemispheric FC was defined as the average of FC between each pair of intrahemispheric regions in right or left hemisphere. Then the correlation between the changes of the interhemispheric and intrahemispheric FC with CS score was analyzed by Pearson correlation test.

4) Granger Causality Analysis: Granger Causality Analysis (GCA) was used to elucidates directional connectivity between brain regions in MRI by determining whether the past value of a time course could correctly forecast the current value of another66,67. Here, the directional connectivity was calculated between the ROIs from the resting-state FC results. The result of functional connectivity was directly used to set the coordinates of ROIs. Finally, the GCA maps were converted to z values and Fisher’s r-to-z was used to improve the normality.

Statistical analysis

The quantitative variables of demographic characteristics were compared with two-sample-t test and qualitative variables were using the Fisher exact test in the two groups. The normality of CS was checked by Shapiro-Wilk tests. Then a two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the influence, within-subjects factor (TIME: Pre, Post and FU) and between-subjects factor (GROUP: BCI-SRF, Finger). The significant statistical difference was set by p < 0.05. Paired t-tests were used in post-hoc tests to compare the before and after the treatment.

A two-way repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the FC Z-maps within-subjects factor (TIME: Pre, Post) and between-subjects factor (GROUP: BCI-SRF, Finger). Paired t-tests were used in post-hoc tests analysis. Multiple comparisons were corrected using Gaussian random field theory (voxel p < 0.001, cluster p < 0.05).

The relationships between the changes of CS improvement and intra/inter-hemispheric FC in all subjects (including BCI-SRF group and Finger group) were analyzed using Pearson correlation test. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. All data are presented as mean ± SD.

Responses