An XBB.1.5-based inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine partially protects against XBB.1.5 and JN.1 strains in hamsters

Introduction

Vaccination is the first line of defense against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In May 2023, the WHO Technical Advisory Group on COVID-19 Vaccine Composition (TAG-CO-VAC) recommended the use of a monovalent XBB.1 descendant lineage, such as XBB.1.5, as the vaccine antigen; therefore, we used hCoV-19/Japan/23-018/2022 (Omicron XBB.1.5.19) isolated by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan, for the production of a whole-virus inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

The Omicron BA.2.86 variant and its descendant lineages, including JN.1, which possess more than 30 amino acid substitutions in the spike protein compared to XBB.1.5, have emerged and are rapidly increasing in prevalence worldwide1,2,3,4. In this study, we evaluated whether our whole-virus inactivated XBB.1.5 vaccine provided protection against XBB.1.5 and the antigenically distinct JN.1 variant in hamsters.

Results

Antibody responses induced in whole inactivated vaccine-immunized hamsters

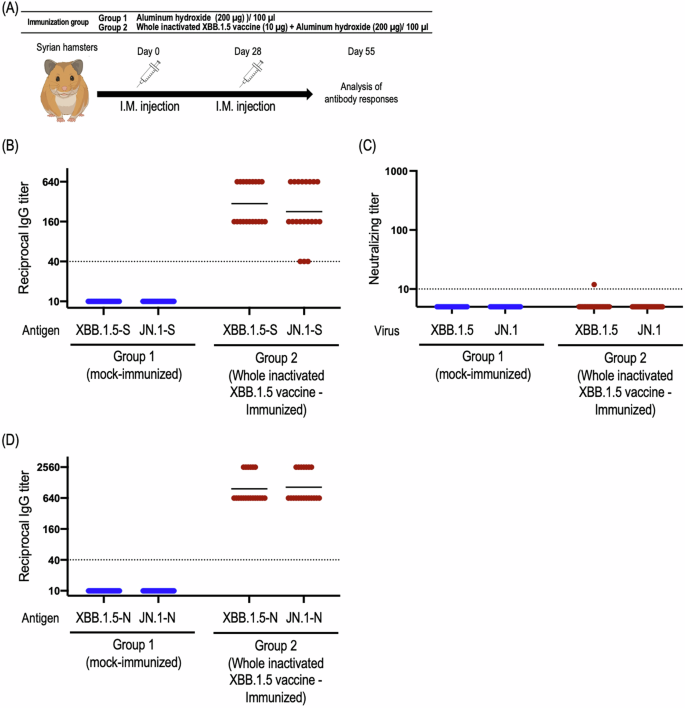

To examine vaccine efficacy, we immunized 6-week-old male hamsters with 10 µg of inactivated whole virions mixed with 200 µg of aluminum hydroxide as an adjuvant in 100 µl of physiological saline or only 200 µg of aluminum hydroxide as an adjuvant in 100 µl of physiological saline. All animals were vaccinated intramuscularly twice, 28 days apart.

First, to assess antigen-specific humoral responses induced by the whole inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine from the XBB.1.5 strain, we performed ELISAs and focus reduction neutralization assays using the ectodomain of the S protein, and authentic SARS-CoV-2, respectively (Fig. 1A). Although all immunized hamsters induced S-specific IgG in serum (Fig. 1B), only one sample from 20 immunized hamsters neutralized authentic XBB.1.5 in our assay (Fig. 1C). Of note, although the antigenicity of the S protein between the XBB.1.5 and JN.1 strains is distinct, IgG titers of serum from immunized hamsters were similar against XBB.1.5-S protein and JN.1-S protein (Fig. 1B). One key feature of inactivated whole virion vaccines is their inclusion of viral proteins other than the S protein. To explore this feature, we examined the presence of anti-N antibodies in immunized hamsters and found that the inactivated whole SARS-CoV-2 vaccine induced N-specific IgG in serum (Fig. 1D). Despite minor amino acid differences in the N protein between the XBB.1.5 and JN.1 strains, the IgG titers in serum against the N proteins of both strains were comparable.

A Schematic diagram showing the experimental workflow. Syrian hamsters were immunized with the whole inactivated XBB.1.5 vaccine by intramuscular inoculation, followed by a booster dose 28 days later. At 4 weeks after the second immunization, sera were harvested from the immunized hamsters. B Titers of spike protein-specific IgG antibodies in the sera were determined by ELISA. Endpoint IgG titers were defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution with an OD450 cut-off value ≥ 0.1. Points indicate data from individual hamsters. Geometric mean titers are shown as vertical bars. C The neutralizing titers (FRNT50 values) of the serum samples were determined in Vero E6-TMPRSS2-T2A-ACE2 cells. Each dot represents data from one hamster. The lower limit of detection (value = 10) is indicated by the horizontal dashed line. Samples under the detection limit (<10) were assigned an FRNT50 of 5. D Titers of N protein-specific IgG antibodies in the sera were determined by use of an ELISA. Endpoint IgG titers were defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution with an OD450 cut-off value ≥ 0.1. Points indicate data from individual hamsters. Geometric mean titers are shown as vertical bars.

Infection with antigenically matched XBB.1.5 and distinct JN.1 strains in whole inactivated vaccine-immunized hamsters

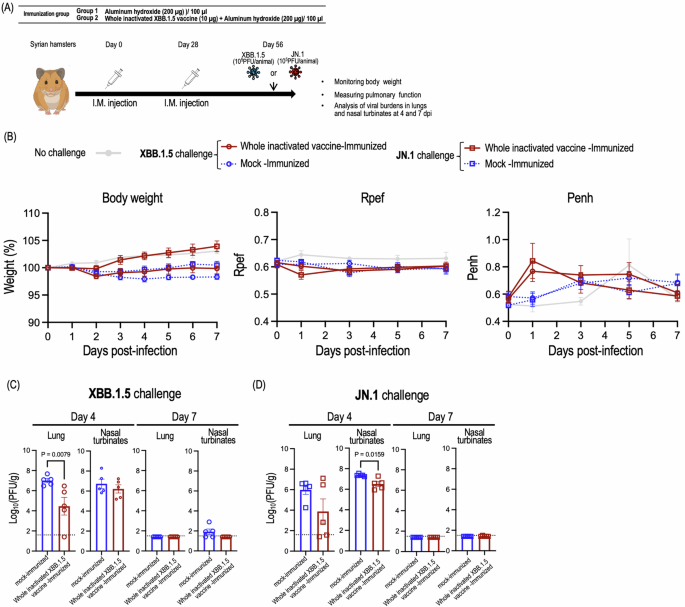

To evaluate the protective effect of the whole inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, we performed challenge studies in hamsters using the XBB.1.5 strain and the antigenically distinct JN.1 strain (Fig. 2A). We monitored body weight and pulmonary functions by measuring Rpef (Ratio of Peak Expiratory Flow) and Penh (Enhanced Pause), which are surrogate markers for bronchoconstriction and airway obstruction, respectively, using a whole-body plethysmography system. We also examined the viral titers in respiratory organs.

A Schematic diagram showing the experimental workflow. Syrian hamsters immunized with the whole inactivated XBB.1.5 were challenged with 105 PFU of XBB.1.5 (HP40900) (B, C), or 105 PFU of JN.1 (Stanford165) (B, D). B Body weights (left panel), Rpef (middle panel) and Penh (right panel) of virus-infected hamsters were monitored daily for 7 days after viral challenge. Data are the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed by use of a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. C, D Five hamsters per group were euthanized at 4 or 7 days post-infection for virus titration. Virus titers in the nasal turbinates and lungs were determined using plaque assays. Data are the mean ± SEM; points represent data from individual hamsters. The lower limit of detection is indicated by the horizontal dashed line. Data were analyzed by using the Mann–Whitney test.

Regarding the XBB.1.5 challenge, both the immunized and control groups of hamsters showed reduced body weight compared to uninfected hamsters. The control hamsters challenged with XBB.1.5 showed slightly greater body weight loss compared to the immunized hamsters although this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 2B, left panel). No changes were observed in the Rpef or Penh of the control or immunized groups compared with the uninfected group at any timepoint after infection (Fig. 2B, middle and right panels). Immunization with the whole inactivated XBB.1.5 vaccine suppressed viral replication in the lungs, but not the nasal turbinate at 4 days post-infection (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that the whole inactivated XBB.1.5 vaccine can protect against homologous virus infection.

After the JN.1 challenge, the immunized hamsters and uninfected hamsters gained body weight, but the control hamsters did not (Fig. 2B, left panel). No changes were observed in the Rpef or Penh across the three groups at any timepoint after infection (Fig. 2B, middle and right panels). Vaccinations led to remarkable reductions in virus titers relative to mock-immunization at 4 days post-infection, although the difference in virus titers in the lungs between the control hamsters and the immunized hamsters did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2D).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a whole inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine derived from the XBB.1.5 strain in a Syrian hamster model. Our findings provide insights into the antibody responses elicited by the whole inactivated vaccine and its ability to protect against homologous and antigenically distinct viral challenges.

The whole inactivated vaccine induced antigen-specific IgG responses against both the SARS-CoV-2 S and N proteins (Fig. 1B, D). While most hamster samples did not show neutralizing activity against XBB.1.5 or JN.1 in our assay (Fig. 1C), challenge studies demonstrated that the whole inactivated XBB.1.5 vaccine provided protection against homologous XBB.1.5 and antigenically distinct JN.1 challenge (albeit partial) (Fig. 2), suggesting that alternative antibody functions, such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, or cellular responses, might contribute to protection. In addition, since we found that N-specific immunity was induced in immunized animals (Fig. 1D), further studies are warranted to assess the extent to which the induction of immunity to the N protein contributes to the suppression of viral titers in the lungs.

We note three limitations in this study. First, since most humans have already been vaccinated or infected with SARS-CoV-2, it is important to study how pre-immunity to SARS-CoV-2 affects the induction of antibodies specific to the newly vaccinated antigens. Second, although the hamster model is one of the best models to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 infection5, laboratory Syrian hamsters are genetically relatively homogeneous compared to humans. In addition, age or underlying health conditions such as obesity have been reported to affect vaccine efficacy6,7. Therefore, additional studies, including clinical trials, would be needed to evaluate the effect of these factors on the efficacy of inactivated vaccines. Third, since XBB.1.5-type mRNA vaccines, which have been used in humans, can induce high levels of neutralizing antibodies3, the efficacy of inactivated whole virion vaccines might be weaker than that of mRNA vaccines. However, inactivated whole virion vaccines offer unique advantages, including a lower incidence of adverse events8. Accordingly, it is crucial to comprehensively assess vaccine efficacy in conjunction with safety and other factors in clinical trials to determine their overall risk-benefit profile.

Overall, our results suggest that whole inactivated XBB.1.5 vaccine can induce antigen-specific antibodies leading to protection from homologous and antigenically distinct strains.

Materials and methods

Cells

VeroE6/TMPRSS2 (JCRB 1819) cells were propagated in the presence of 1 mg/ml geneticin (G418; Invivogen) and 5 μg/ml plasmocin prophylactic (Invivogen) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS). Vero E6-TMPRSS2-T2A-ACE2 cells (provided by Dr. Barney Graham, NIAID Vaccine Research Center) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin, and 10 μg/mL puromycin. VeroE6/TMPRSS2 and Vero E6-TMPRSS2-T2A-ACE2 cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The cells were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination by using PCR and confirmed to be mycoplasma-free.

Viruses

hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP40900-PIDYSWHNUB/2022 (Omicron XBB.1.5: HP40900)9 and hCoV-19/USA/CA-Stanford-165_S10/2023 (Omicron JN.1; Stanford165)10 were propagated in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells in VP-SFM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All experiments with SARS-CoV-2 were performed in enhanced biosafety level 3 (BSL3) containment laboratories at the University of Tokyo and the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan, which are approved for such use by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Japan.

Whole inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine

The SARS-CoV-2 seed strain hCoV-19/Japan/23-018/2022 (Omicron XBB.1.5.19), isolated by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan, was cultured in Vero cells, which were grown in large-scale bioreactors (600 L) at an MOI of 0.01–0.0001. The virus supernatant was harvested 1–4 days after inoculation and then was inactivated with beta-propiolactone, followed by ultrafilter depth filtration and affinity chromatography purification. Alum was added at a concentration of 0.4 mg/mL, yielding a KD-414 drug product.

Animal experiments and approvals

Animal studies were carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Animal Experiment Committee of the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo (approval number: PA19–75). All animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in a temperature-controlled environment with a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle, with 50% humidity and ad libitum access to water and standard laboratory chow. Immunizations and virus inoculations were performed under anesthesia with isoflurane, and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. In vivo studies were not blinded, and animals were randomly assigned to immunization/infection groups. No sample-size calculations were performed to power the studies. Instead, sample sizes were determined based on prior in vivo virus challenge experiments.

Immunization and challenge

For the immunization and protection studies, 6-week-old male wild-type Syrian hamsters (Japan SLC) were anesthetized with isoflurane and intramuscularly immunized with the whole inactivated XBB.1.5 vaccine twice with a 4-week interval between immunizations; 4 weeks after the second immunization, the hamsters were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 [HP40900 (XBB.1.5): 105 PFU/30 µL or Stanford165 (JN.1): 105 PFU/30 µL]. Baseline body weights were measured before infection. Body weights were monitored daily for 7 days. For examination of lung functions, respiratory parameters were measured by using a whole-body plethysmography system (PrimeBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, hamsters were placed in the unrestrained plethysmography chambers and allowed to acclimatize for 1 min before data were acquired over a 3-min period by using FinePointe software. For examination of viral burdens in respiratory organs, hamsters were euthanized by cervical dislocation on days 4 and 7 post-infection, and their lungs and nasal turbinates were collected and examined for virus titers. The virus titers of stocks and those in the nasal turbinates and lungs were determined by use of plaque assays on VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells.

ELISA

ELISA was performed as previously reported11. Briefly, 96-well Maxisorp microplates (Nunc) were incubated with the recombinant HexaPro prefusion-stabilized versions of the S ectodomain or the recombinant N protein (Sino Biological) (50 μl per well at 2 μg/ml), or with PBS at 4 °C overnight and were then incubated with 5% skim milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature. The microplates were reacted for 1 h at room temperature with serially 4-fold diluted hamster serum samples (initially diluted 40-fold) or PBS, followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-hamster IgG antibody (Rockland) for 1 h at room temperature. Then, 1-Step Ultra TMB-Blotting solution (Thermo Fisher) was added to each well, followed by incubation for 3 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 M H2SO4 and the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) was immediately measured. The average OD450 values of two PBS wells were subtracted from the average OD450 values of the sample wells for background correction. A subtracted OD450 value of 0.1 or more was regarded as positive; the minimum dilution to give a positive result was used as the ELISA titer.

Focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT)

Neutralization activities of serum were determined by using a focus reduction neutralization test as previously described12. The samples were first incubated at 56 °C for 1 h. Then, the treated serum samples were serially diluted five-fold with DMEM containing 2% FCS in 96-well plates and mixed with 100–400 FFU of virus/well, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. The serum-virus mixture was inoculated onto Vero E6-TMPRSS2-T2A-ACE2 cells in 96-well plates in duplicate and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, 100 μl of 1.5% Methyl Cellulose 400 (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) in culture medium was added to each well. The cells were incubated for 14–16 h at 37 °C and then fixed with formalin.

After the formalin was removed, the cells were immunostained with a rabbit monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein (Sino Biological Inc., dilution: 1:10,000, Cat #: 40143-R001) followed by a horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., dilution: 1:2000, Cat #: 111-035-003). The infected cells were stained with TrueBlue Substrate (SeraCare Life Sciences) and then washed with distilled water. After cell drying, the focus numbers were quantified by using an ImmunoSpot S6 Analyzer, ImmunoCapture software, and BioSpot software (Cellular Technology). The results are expressed as the 50% focus reduction neutralization titer (FRNT50). The FRNT50 values were calculated by using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). Samples under the detection limit (<10-fold dilution) were assigned an FRNT50 of 5.

Statistics

GraphPad Prism 9 software was used to perform all statistical analysis. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reagent availability

Inactivated vaccine was prepared at KM Biologics Co., Ltd. and used only for this study. Other materials are available from the authors or from commercially available sources.

Responses