Angelicae dahuricae radix alleviates simulated microgravity induced bone loss by promoting osteoblast differentiation

Introduction

It is well known that gravity is the main force for maintaining the normal function of bones on Earth. With the increasing space exploration by humans, the bone health of astronauts has become one of several critical problems to be addressed in space flight. Long-term exposure to microgravity environment results in significant bone loss. Numerous studies have shown that the bone mineral density in astronauts decreases by 1% to 2% each month in a microgravity environment, particularly affecting weight-bearing bones. This is roughly equivalent to the amount of bone loss in a post-menopausal woman for one year1,2,3, and recovery from bone loss after returning to the ground is notably difficult4. The process of bone remodeling relies on the dynamic regulation between osteoblasts, which secrete bone matrix and promote bone mineralization to form new bone tissue, and osteoclasts, which secrete acids and enzymes to dissolve the bone matrix and reabsorb aged or damaged bone tissue5,6,7. In general, the activities of these two types of cells remain in relative balance, enabling the skeleton to maintain a stable structure and function in ground gravity environment. However, under microgravity environment in space, due to the weakening of osteoblast differentiation, bone formation is reduced while osteoclast activity is enhanced, thus bone resorption is increased. Consequently, the effect of microgravity in space disrupts the balance between bone resorption and osteogenesis, causing bone homeostatic equilibrium imbalance, ultimately leading to the occurrence of microgravity induced bone loss8,9,10,11. Notably, osteoblasts respond to mechanical stimuli in a gravitational environment, and synthesize and secrete components such as collagen and osteocalcin under the influence of various growth regulators. These secretions form a network in the bone matrix and promote the deposition of calcium and phosphate, thereby forming mature bone tissue. Therefore, osteoblasts play a very critical role in maintaining and promoting the health and function of the skeletal system. In contrast, under weightlessness conditions, osteoblasts lack sufficient mechanical stimulation, leading to alterations in the expression patterns of genes related to osteogenesis, which in turn affects osteoblast differentiation, reducing osteogenic capacity. Thus, activating osteoblast differentiation could prevent microgravity-induced bone loss via its bone-forming functions during the process of bone remodeling.

Current clinical treatments for microgravity-induced bone loss mainly include physical exercise, mechanical stimulation, and pharmacological interventions12,13,14. However, the variety of drugs available for treating weightlessness-induced bone loss is limited. The bisphosphonates and denosumab were found to have significant protective effects against microgravity-induced bone loss12,15,16. Although these drugs have been proven effective, prolonged use may lead to serious side effects17,18,19. Thus, it is still necessary to find effective and safe therapeutic drugs to prevent microgravity-induced bone loss.

Angelica dahurica Radix (AR) belongs to the umbelliferae family, and its root is utilized as both a traditional Chinese medicine and food additive. AR contains over 70 biologically active components, which are mainly classified into alkaloids, phenolic acids, flavonoids, lignans, coumarins, and volatile oils, etc.20,21. Previous studies have demonstrated multiple benefits of AR, including anticancer22, bactericidal, anti-inflammatory23, analgesic24, and hepatoprotective activities25. Cannabinol isolated from AR has been shown to inhibit COX-2 activity and block excessive pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), thereby decreasing the inflammatory reaction26. Besides, recent research indicates that the water extract of AR attenuates bone resorption by inhibiting osteoclast differentiation27, suggesting its potential role in the prevention of osteoporosis. However, it remains unclear whether the alcoholic extract of AR can promote osteoblast differentiation and exert protective effects against microgravity-induced bone loss. In this study, we utilized alcohol to extract AR and investigate its role in promoting osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Our findings indicate that AR could effectively mitigate bone loss in mice subjected to simulated microgravity conditions, employing a hind limb unloading (HLU) mouse model, without inducing significant hepatic or renal toxicity. Furthermore, the active components in AR-medicated rat serum were subsequently identified through widely targeted metabolomics. Additionally, by intersecting acted targets of key compounds in AR with candidate treatment targets based on the osteoporosis disease, we identified prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) as a significant target. Moreover, we also analyzed the molecular pathways involved in the targets of action through the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) clustering and found the arachidonic acid metabolism pathway may be a potential pathway through which the key components of AR exert their pharmacological effects. Our study provides AR as a promising new drug candidate for preventing microgravity-induced bone loss.

Results

Angelicae dahuricae Radix alleviated the loss of BMD under simulated microgravity conditions

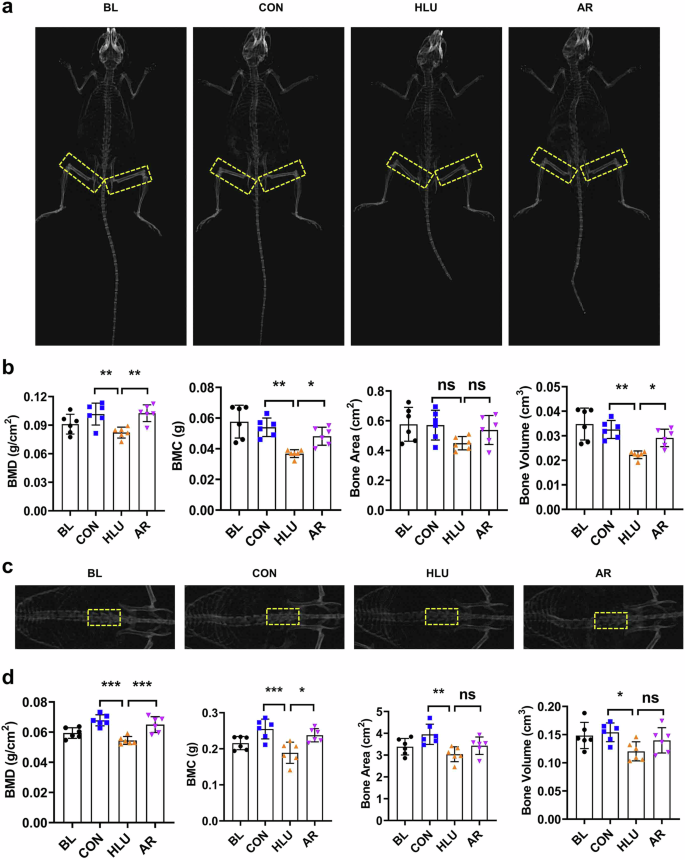

The HLU mouse model was first established, and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) was employed to assess bone mineral density (BMD) in the HLU mice (Fig. 1a). The BMD of the femur in HLU mice was found to be reduced compared to the ground control group. However, this decline was ameliorated with the administration of AR (2 g/kg). Besides, bone mineral content (BMC), bone area, and bone volume of femur all exhibited significant increases after oral administration of AR (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Fig. 1b). In HLU mice, the 3rd, 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae, as another load-bearing bone, were also analyzed through DEXA, and quantitatively assessed for various bone-related parameters (Fig. 1c). It was observed that HLU also resulted in a significant decrease in the BMD in vertebra, while the treatment of AR improved BMD to a similar level as the ground control group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Fig. 1d). The above results indicate that AR can significantly prevent the loss of bone mass in the femur and vertebrae induced by simulated microgravity.

a Representative DEXA images of femurs in HLU mice. The yellow dotted line represents the femoral region. b Quantitative analysis of BMD, BMC, Bone Area, Bone Volume of femurs in HLU mice. c Representative DEXA images of vertebrae in HLU mice. The yellow dotted line represents the 3rd, 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae region. d Quantitative analysis of BMD, BMC, Bone Area, Bone Volume of vertebrae in HLU mice. Bone Mineral Density (BMD), Bone Mineral Content (BMC). Values are mean ± SD (n = 6). * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001.

Angelicae dahuricae Radix mitigated the adverse effect of simulated microgravity on bone microstructure

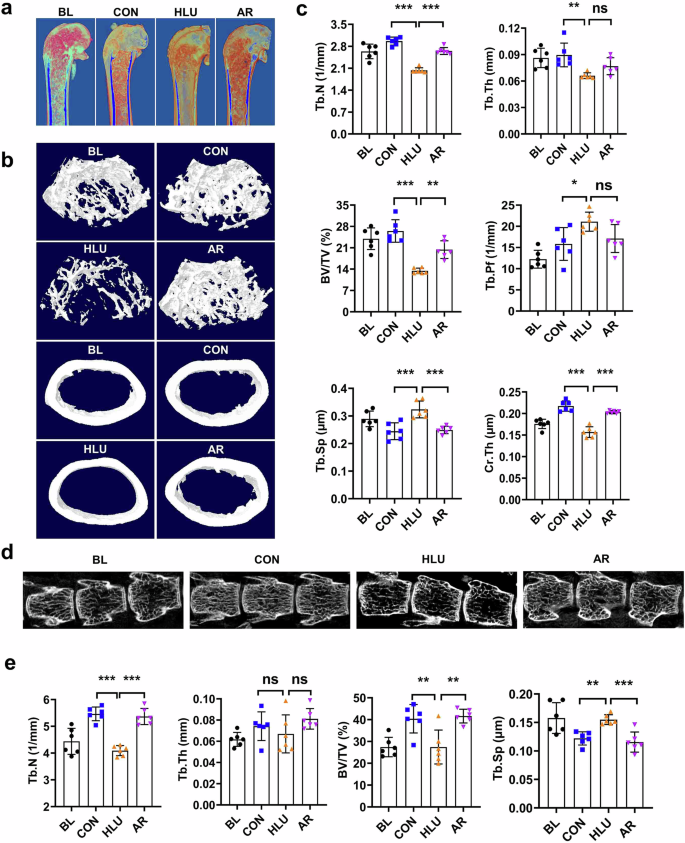

To elucidate the protective effect of AR on bone microstructure, the femurs of HLU mice were analyzed using micro-CT. Compared to the ground control group, HLU resulted in significant decreases in Tb.N, BV/TV, Tb.Th and Cr.Th indices in the femur, while Tb.Sp was significantly increased. In contrast, oral administration of AR markedly improved bone microstructure, as evidenced by significant increases in BV/TV, Tb.N, and Cr.Th in the femur, alongside a decrease in Tb.Sp (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Fig. 2a, b, c). Additionally, HLU also decreased Tb.N and BV/TV in vertebrae while increased Tb.Sp. However, the treatment of AR improved the BV/TV, Tb.N, and Tb.Sp indices in vertebrae (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Fig. 2d, e). This indicates that AR can partially rescue degeneration of trabecular bone.

a Representative 3D reconstructed images of trabecular bone of distal femurs in HLU mice. b Representative 3D reconstructed microstructural images of trabecular bone and cortical bone in HLU mice. c Quantitative analysis of trabecular bone and cortical bone of femurs in HLU mice. Values are mean ± SD. d Representative 3D reconstructed microstructural images of the 3rd, 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae in HLU mice. e Quantitative analysis of trabecular bone of the 3rd, 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae in HLU mice. Bone volume per tissue volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular bone pattern factor (Tb.Pf), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), cortical bone thickness (Cr,Th). Values are mean ± SD (n = 6). * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001.

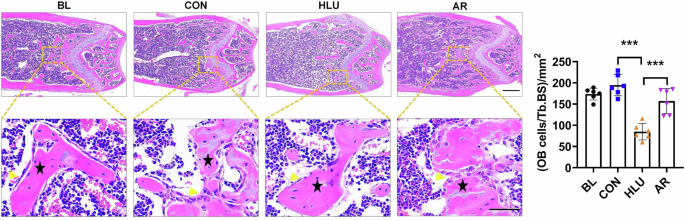

Angelica dahurica Radix inhibited the negative effects of simulated microgravity on femur histomorphometry

In order to assess the formation of trabecular bone and the number of osteoblasts distributed, the morphology of the femoral tissue was observed by H&E staining of bone tissue sections. The results showed that compared with the control group, the trabecular bones were sparsely distributed in the HLU group, the number of osteoblasts at the trabecular edge was significantly reduced, while in the AR group, the trabecular bones were densely distributed, and the number of osteoblasts at the edge of the trabeculae was increased (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Fig. 3). This implies that AR has a protective effect on microgravity-induced bone loss by promoting osteoblast differentiation.

Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin staining of femoral tissue sections in HLU mice. Scale bar, upper 500 μm, lower 50 μm. The black pentagram represents the area of trabecular bone distribution, and yellow arrow indicates osteoblasts surrounding the edge of trabeculae. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6). * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001.

Angelicae dahuricae Radix attenuated the inhibitory effect of simulated microgravity on tibial biomechanical properties

The effect of AR on the mechanical properties of the tibia under simulated microgravity was examined through a three-point bending experiment (Fig. 4a). The results showed that the mechanical properties, specifically stiffness and maximum load, in the AR administration group were significantly enhanced compared to the HLU group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Fig. 4b). The above results indicate that AR can attenuate the inhibitory effects of simulated microgravity on tibial mechanical properties, thereby improving the ability of bones to resist external forces.

a Schematic diagram of three-point bending test of bone mechanical properties. b Results of measurements of maximum load, modulus of elasticity, stiffness, and load-deflection curves of the tibias in HLU mice. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6). * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001.

Angelicae dahuricae Radix attenuated the negative effects of simulated microgravity on osteoblast differentiation

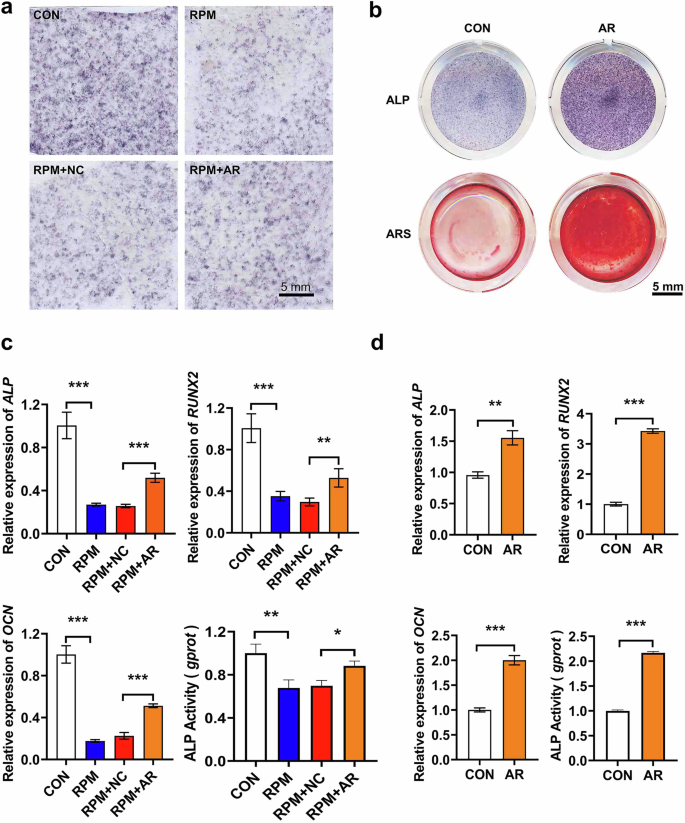

To further investigate the rescue effect of AR on osteoblast differentiation under simulated weightlessness condition, we cultured osteoblasts MC3T3-E1 for 48 hours in AR-medicated serum medium at a concentration of 10% under both normal gravity and RPM conditions. The results of ALP and ARS staining showed that AR increased the number of mineralized nodules, effectively restoring the differentiation capability of osteoblasts (Fig. 5a, b). In addition, AR medicated serum inhibited the downregulation of osteoblast differentiation marker genes and suppressed the decrease in ALP enzyme activity induced by RPM condition as well (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Fig. 5c). In the ground group, AR also enhanced the expression levels of osteoblast differentiation marker genes, such as Alp, transcription factor-RUNX2 (RUNX2), and osteocalcin (OCN), as well as the enzyme activity of ALP (**P < 0. 01, ***P < 0.001. Fig. 5d). The results suggest that AR promotes osteoblast differentiation under normal gravity conditions, and attenuates the negative effects of the simulated microgravity condition on osteoblast differentiation.

a Representative images of ALP staining of osteoblast under RPM simulated microgravity conditions. Scale bar = 5 mm. b Representative images of ALP and ARS staining of osteoblast under normal gravity conditions. Scale bar = 5 mm. c Quantitative analysis of the mRNA expression levels of Alp, RUNX2, OCN, and ALP enzyme activity in osteoblasts under RPM simulated microgravity conditions (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SD. P values less than 0.05 were considered as significant, * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001. d Quantitative analysis of the mRNA expression levels of Alp, RUNX2, OCN and ALP enzyme activity in osteoblasts under normal gravity conditions (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SD. P values less than 0.05 were considered as significant, * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001.

Screening of active components in Angelicae dahuricae Radix

A widely targeted metabolomics analysis was conducted using AR-medicated serum from rats to identify the active ingredients present in AR extract, which were absorbed in blood and subsequently exerted pharmacological effects. The overlapping display analysis of Total Ion Chromatography (TIC) from QC samples confirmed the excellent repeatability of metabolite extraction and detection (Supplemental Fig. 1). A total of 224 components in AR-medicated serum were identified using UPLC-MS/MS (Fig. 6a and Supplemental Table 1). The detected components included alkaloids (30.122%), phenolic acids (24.844%), flavonoids (1.309%), quinones (0.291%), lignans and coumarins (13.574%), terpenoids (0.004%), and other components (29.857%) (Fig. 6b). Among the identified components, the representative compounds with the highest concentrations were vanillylamine (alkaloids, 1.58 × 105), blumenol C (terpenoids, 6.54 × 104), dihydroseselin (lignans and coumarins, 1.97 × 105), 1-naphthol (phenolic acids, 1.03 × 105), 3,4’-dihydroxyflavone (flavonoids, 3.66 × 105), decursinol (Others, 3.30 × 104), 7,8-Dihydroxy-4-phenylcoumarin (lignans and coumarins, 1.01 × 105), and chrysophanol-9-anthrone (quinones, 5.17 × 106) (Fig. 6c), indicating the medicated serum contains most of the reported active ingredients of AR28. The components of AR were primarily composed of alkaloids and phenolic acids, followed by lignans and coumarins, with smaller amounts of flavonoids, quinones, and terpenoids. This composition aligns with previously reported active ingredient profiles of AR29, suggesting that the test results are reliable, and the active ingredients in AR extract were effectively absorbed into the blood, thereby exerting significant pharmacological effects.

a Representative multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) chromatograms for the UPLC-MS/MS analysis of AR-medicated serum. N, Negative ion mode, P, Positive ion mode. b Types and proportions of the identified ingredients in AR-medicated serum. c Representative MRM chromatograms of ingredients in AR-medicated serum. The horizontal axis represents the retention time for metabolite detection (min), the vertical axis represents the ion flow intensity for metabolite ion detection (cps), and the peak area represents the relative content of the substance in the sample.

Target screening and molecular pathway analysis of effective components of Angelicae dahuricae Radix in anti-osteoporosis

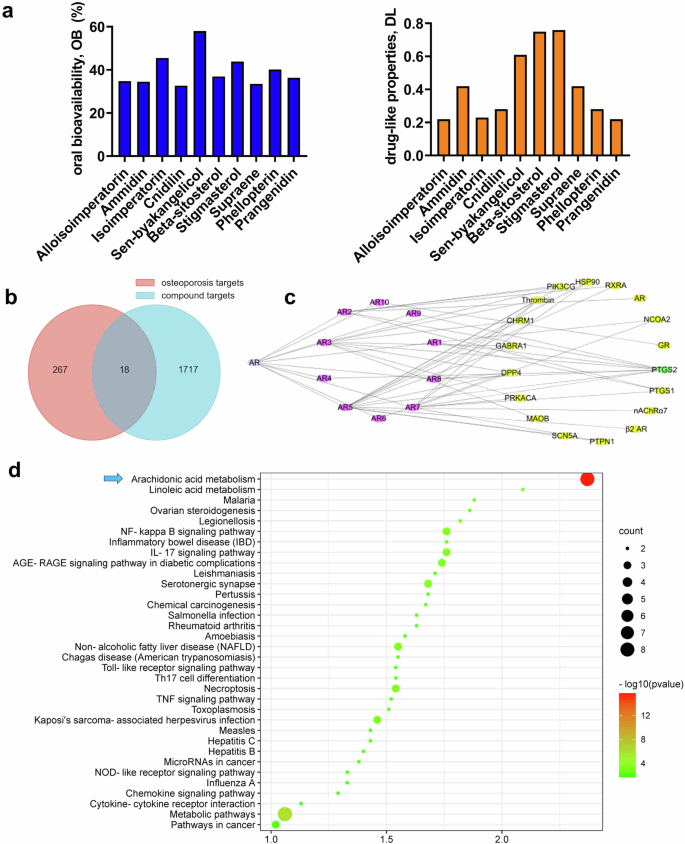

The Traditional Chinese Medicines Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) online database was utilized to explore the active ingredients of AR. Ten key active ingredients amongst all components in AR were identified through TCMSP analysis, based on oral bioavailability (>30%) and drug-like properties (>0.18) scoring (Fig. 7a). Among these 10 key components, 10% were terpenoids (supraene), 20% were alcohols found in volatile oil (beta-sitosterol, stigmasterol), and 70% were coumarins (alloisoimperatorin, ammidin, isoimperatorin, cnidilin, sen-byakangelicol, phellopterin, and prangenidin) (Supplemental Table 2). The majority of coumarin compounds are classified, which corresponds to the proportion of coumarin-like compounds in the active ingredient types of AR as detected by LC-MS/MS. To identify potential targets of the 10 key active compounds in AR for the treatment of osteoporosis, we intersected the targets of compounds with those related to bone diseases. Initially, 1717 candidate targets for 10 compounds were identified, with 267 candidate targets based on the osteoporosis disease model. The construction of a Venn diagram revealed a total of 18 common target genes between the compounds and osteoporosis disease (Fig. 7b and Supplemental Table 3). By constructing an interaction network of the 10 active ingredients in AR and the 18 action targets, the results indicate that most active ingredients in AR primarily act on PTGS2, which has the maximum number of nodes in the interaction network of active ingredients and action targets (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, the molecular pathways of the targets in the treatment of osteoporosis were analyzed through KEGG cluster analysis, revealing that the compounds exert their anti-osteoporosis effects primarily through the arachidonic acid metabolism pathway, characterized by the highest number and smallest P value of the involved genes (Fig. 7d). It was speculated that AR exerts its therapeutic effects on osteoporosis by acting on PTGS2 via the arachidonic acid metabolic pathway.

a Oral bioavailability and drug-like properties of top 10 key components in AR from TCMSP database. b Venn diagram of targets for active compounds in AR and osteoporosis-related targets. c Diagram of visualization network of compounds-targets, composed of 18 target nodes (diamond, purple), 10 compounds nodes (diamond, yellow) and 1 Chinese herbal medicine node (round, blue). d Enrichment of KEGG pathways of the 10 key active ingredients in AR.

Angelicae dahuricae Radix exhibited minor toxicity in HLU mice

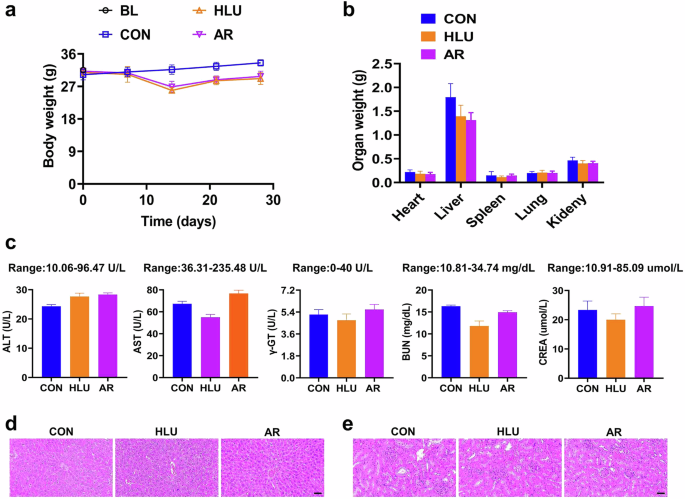

To evaluate the potential side effects of AR on HLU mice, we measured liver and kidney function indices as well as body weight. The body weight of mice in the HLU group was slightly lower than that of the control group, however, no significant difference in body weight was observed between the AR administration group and the HLU group (Fig. 8a). The organ weight indices for the liver and kidneys did not reveal any significant differences among the groups (Fig. 8b). Notably, all measured indicators, including AST, ALT, γ-GT, CREA, and BUN, were within normal range as determined by the blood chemistry profile (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) across all groups (Fig. 8c). Additionally, H&E staining of tissue sections showed clear structures in both liver and kidney tissues, with no abnormalities (Fig. 8d, e). These results suggest that AR does not produce significant toxic effects in HLU mice.

a Results of body weight in HLU mice. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6). b Results of organs weight in HLU mice. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6). c Results of blood chemistry profile of ALT, AST, γ-GT, BUN, CREA in HLU mice serum. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). d Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver tissue sections in HLU mice. Scale bar = 200 µm. e Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin staining of kidney tissue sections in HLU mice. Scale bar = 200 µm.

Discussion

Ground gravity plays an irreplaceable role in the development of skeletal structures, the problem of microgravity-induced skeletal disorder has been extensively studied and emphasized in future space mission exploration. Studies have demonstrated that bone loss caused by microgravity in space poses a serious health risk for astronauts30. With differences between the space and Earth environments, the space environment provides a unique experimental condition to observe the physiological responses of organisms under microgravity environment. For instance, it has been shown that in the Bion-M1 space mission, a month-long spaceflight resulted in trabecular disconnection and cortical thinning in adult male C57/BL6 mice31. Although spaceflight is the most ideal method for studying weightlessness-induced bone loss, the limited number of launch missions restricts opportunities for such experiments. Consequently, we opted to establish a simulated microgravity environment on Earth to study weightlessness-induced bone loss. Research has indicated that Dipsaci extract can prevent bone loss in a hindlimb unloading model rat32. The hindlimb unloading rat or mouse serves as an ideal animal model for examining the effects of long- or short-term weightlessness on the organisms.

The exercise has been demonstrated to be beneficial in combating bone loss caused by microgravity environment33, however, due to the inherent limitations of space conditions, such as the inconvenience associated with certain activities, some pharmacological treatments for bone loss are restricted to merely supplementing calcium or are effective only for osteoporosis. In contrast, Chinese herbal medicine offers several advantages, including multi-targeting capabilities, extensive drug delivery potential, low toxicity, and systemic conditioning. These properties have led to its extensive research in the treatment of bone diseases. For example, Cnidium perforatum has been widely used in clinical Chinese medicine to promote osteoblast differentiation and inhibit osteoclast activity34, Additionally, Cistanche has been shown to regulate bone metabolism by enhancing osteoblast activity and suppressing osteoclast activity without significant adverse effects35. Thus, Chinese herbal extracts provide a new approach and strategy for treating microgravity-induced bone loss. Furthermore, Angelicae dahuricae Radix, an important natural herbal medicine documented in the Chinese pharmacopoeia, exhibits liver-protection, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory pharmacological activities28,29. In this study, AR was administered to HLU mice for treatment, and we found that AR can effectively prevent BMD loss caused by microgravity, inhibit the degeneration of the microstructure of bone trabeculae, and promote bone formation, Therefore, AR significantly prevented weightlessness-induced bone loss. Previous research demonstrated that the water extract of AR had a therapeutic effect on OVX-induced osteoporosis mice27. Additionally, we performed functional validation, but we used the alcoholic extract of AR and chose different doses of AR for treatment in the OVX mice model as well. The results showed that compared with low and medium doses, the high-dose AR extract significantly prevented the loss of femoral and vertebral BMD (Supplemental Fig. 2), inhibited the degradation of bone microstructure (Supplemental Fig. 3), and promoted osteoblast differentiation and bone formation in a dose-dependent manner (Supplemental Fig. 4). Furthermore, AR also improved the biomechanical properties of the tibia in OVX mice (Supplemental Fig. 5). These results indicate that AR has therapeutic effects on various types of osteoporosis. Importantly, no toxic effects were observed following AR intragastric administration, as indicated by assessments of body weight, organ indices, and blood chemistry. Additionally, tissue section analyses revealed no abnormalities in the liver and kidneys, consistent with the findings in the OVX mice (Supplemental Fig. 6). Thus, AR could be considered a promising drug candidate with a high safety profile.

Previous studies have demonstrated that three-dimensional random position machine, which simulates weightlessness and mechanical unloading conditions, significantly inhibits osteoblast differentiation36,37, this suggests that a decrease or loss of mechanical load reduces the differentiation capacity of osteoblasts, ultimately leading to a loss of bone mass. In this study, the results of ALP and ARS staining indicated that AR-medicated serum promoted osteoblast differentiation and mineralized nodule formation. In addition, AR containing serum alleviated the adverse effects of the RPM environment on osteoblast differentiation, enhanced ALP enzyme activity, and increased the expression levels of key osteogenic marker genes such as ALP, RUNX2, and OCN in osteoblast. Therefore, AR effectively prevents weightlessness-induced bone loss by promoting osteoblast differentiation.

The mechanical properties of bone pertain to study the biological effects of external mechanical forces on bone, which are directly related to bone fragility. Studies indicate that 73.3% of long-term bedridden patients experience a significant decrease in skeletal mechanical properties, resulting in increased bone fragility38,39. In addition, the microgravity environment of spaceflight inhibits bone formation, and leads to bone loss, ultimately causing the reduction of bone hardness40. In this study, AR significantly mitigated the biomechanical decline of the tibia caused by a simulated microgravity, with maximum load, elastic modulus, and stiffness index increasing to levels comparable to normal conditions after AR treatment. Thus, AR can effectively counteract the decline in bone mechanical properties induced by simulated weightlessness.

Various types of active ingredients are extracted from traditional Chinese medicine, including flavonoids, glycosides, coumarins, terpenoids, and phenolics. To date, more than 300 chemical components have been isolated and identified from AR, such as alkaloids, phenols, sterols, benzofurans, polyacetylenes, and polysaccharides, which exhibit broad-spectrum pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and anti-oxidant41,42. In this study, quantitative LC-MS/MS detection of AR-medicated serum revealed a total of 224 components, comprising alkaloids (30.122%), phenolic acids (24.844%), flavonoids (1.309%), quinones (0.291%), lignans and coumarins (13.574%), terpenoids (0.004%), and other components (29.857%). Thus, the active ingredients in AR are dominated by alkaloids, phenolic acids and lignans, and coumarins. Studies have shown that certain potential active components in traditional Chinese medicine exhibit significant therapeutic effects on bone diseases. For instance, coumarin compounds facilitate the differentiation of osteogenic stem cells and enhance bone formation43. Flavonoids have been shown to alleviate bone loss in OVX-induced osteoporosis rats, and improve the trabecular microstructure and biomechanical properties of the fourth lumbar spine44. Given that AR is effective in treating both microgravity-induced bone loss and osteoporosis, we infer that this efficacy is attributable to the various active ingredients present in AR, despite the differing mechanisms underlying osteoporosis and weightlessness-induced bone loss.

The results of the interaction network involving 10 active ingredients in AR and 18 action targets, which represent the common target genes between the compounds and osteoporosis, indicate that the majority of the active ingredients in AR primarily act on PTGS2. Molecular pathway clustering was analyzed using KEGG for the targets of compounds against osteoporosis, and the predicted results revealed that the most likely pathway is the arachidonic acid metabolism pathway. Previous studies showed that PTGS2 is a key enzyme in the synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) from arachidonic acid, which is regarded as a potent synthetic metabolic regulator of bone growth45,46. The hypothalamus regulates bone remodeling by sensing the concentration of PGE2 in bone, PGE2 enhances the sensitivity of weight-bearing bone to mechanical stimuli. Conversely, blocking the synthesis of PGE2 results in bones being unable to respond to mechanical stimuli, thereby reducing bone formation47,48. Gao et al. found that in hindlimb tail suspension mice, variations in skeletal PGE2 concentration correlated with changes in their weight-bearing capacity. The deletion of PGE2 in osteoblast lineage cells or the knockout of Ep4 in sensory nerves diminished the response of weight-bearing bone to mechanical loading49,50. Thus PGE2 serves as a mechanotransduction signal that converts external mechanical loads into biochemical responses. This suggests that the compounds in AR probably treat microgravity-induced bone loss through the arachidonic acid metabolic pathway by targeting PTGS2.

In summary, AR has the potential to counteract bone loss induced by a simulated microgravity environment, improving bone biomechanical properties, recovering BMD, and enhancing the microstructure of bone trabeculae. It also increases cortical bone thickness and effectively promotes bone formation. Meanwhile, AR alleviated the suppression effect of simulated microgravity on osteoblast differentiation. The primary components of AR are alkaloids and phenolic acids, followed by lignans and coumarins. Furthermore, it is speculated that the active ingredient of AR interacts with PTGS2 through the arachidonic acid metabolism pathway, thereby reducing the inhibitory effect of simulated microgravity on osteoblast differentiation. In addition, AR demonstrates high biological safety, exhibiting no significant toxic effects. These findings reveal the effective efficacy of AR in combating microgravity-induced bone loss.

Methods

Preparation of AR extract

AR was finely crushed, and 1000 g of powder that could pass through a No. 3 sieve was accurately weighed. Subsequently, 8 L of 95% ethanol was added, and the mixture was extracted under reflux for 2 h. This extraction process was repeated three times following filtration. The mixture was then distilled under reduced pressure to yield 250 mL of a 1:4 condensed extract (where 1 mL of concentrated extract is equivalent to 4 g of the original herb), which was stored at −20 °C.

Establishment of hindlimb unloading mouse model

2-month-old male C57/BL mice were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of the Fourth Military Medical University of China (Xi’an, Shaanxi, China). Prior to establishing the HLU model, all mice were acclimated to the household environment for a duration of 7 days, during which they were maintained at room temperature under a 12 h light/12-hour dark cycle. A total of 24 mice were randomly assigned to the following groups: baseline group (BL), ground control group (CON), HLU + NC group (HLU), and HLU + AR group (AR), with N = 6 mice per group. The baseline group represents the relevant characteristics and health status of the experimental animals (e.g., body weight, microbial status, medication, etc.) prior to treatment or testing. For the baseline group, whole blood was collected via cardiac puncture prior to HLU, and organs such as femurs and tibiae were harvested for subsequent testing. The mice in the control group were allowed free movement, while those subjected to HLU were raised for four weeks. Following the design requirements of Morey et al. for the HLU animal model51,52, an elastic tape was attached to the rear edge of each mouse’s tail, with the clip at the other end fixed to the top slider for free sliding. The mice were held in place at a 30° angle, with their hind legs elevated from the floor of the cage, allowing them to access food and water freely. The mice’s dietary intake and tails were examined daily. In the HLU + AR group, mice were administered AR at a dosage of 2 g·kg-1·day-1 via gastric irrigation once daily, while those in the CON and HLU groups received an equivalent volume of 0.5% CMC-Na through gastric irrigation once daily. Whole blood was collected from the heart by puncture, and the serum was stored at −80 °C. Furthermore, other samples of the mice were collected, including femurs, tibias, livers, and kidneys. All experimental procedures used in this study were approved by the Lab Animal Ethics & Welfare Committee of Northwestern Polytechnical University.

Establishment of ovariectomy mouse model

2-month-old female C57/BL mice were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of the Fourth Military Medical University of China (Xi’an, Shaanxi, China). The mice were housed under a 12 h light/dark cycle at room temperature throughout the study. Ovariectomy was performed to establish a postmenopausal osteoporosis mouse model. After anesthetizing the mice, their backs were disinfected with 70% alcohol, the hair was shaved, and a small incision of approximately 0.8 cm was made at the level of the spinal rib angle along the lumbar region. The muscle was incised to access the posterior peritoneum, where the ovaries are located adjacent to the uterus. In the sham group, a piece of fat was excised at the fallopian tube, while in the remaining groups, the ovaries were completely removed. The remaining fallopian tubes were gently returned to their original position, followed by suturing. After a week of incision healing and recovery, the baseline group (N = 6 mice per group) had whole blood samples and other samples collected prior to ovariectomy, including mouse femur, tibia, and other organs. The mice in the OVX + AR group were administered AR at doses of 0.5 g·kg−1 (as low dose, AR-L), 1 g·kg−1 (as medium dose, AR-M), and 2 g·kg−1 (as high dose, AR-H) for 8 weeks (N = 9 mice per group). In the sham and OVX groups, the mice received a daily dose of 0.5% CMC-Na equivalent in volume to the AR doses (N = 9 mice per group). The whole blood was obtained by puncturing the heart and stored at −80 °C. All animal experiment procedures were approved by the Lab Animal Ethics & Welfare Committee of Northwestern Polytechnical University.

Analysis of bone mineral density

The BMD of the femur and vertebrae in mice was measured using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) (InAlyzer, MEDIKORS, South Korea) following a 4-week oral administration of AR to HLU mice and an 8-week administration to OVX mice, respectively. The mice were initially anesthetized intraperitoneally with 1.5% sodium pentobarbital and then positioned on a testing bench for bone scanning. Subsequently, the BMD values for the femur and the 3rd, 4th, and 5th lumbar vertebrae of HLU mice were analyzed using INALYZER Dual-ray Digital Imaging Software.

Analysis of micro-CT tomography

To detect the microarchitecture of mouse femurs and vertebrae, samples were scanned using a micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) device (General Electric, Milwaukee, 80 kPV, 80 μA, 3000 ms). Following blood collection from the model mice, animals were euthanized. The hind femur and tibia of each group of mice were collected. The right femoral tissue was then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for subsequent analysis. Micro-CT was employed for detection, and the samples were secured on the analysis rack. The internal structures were scanned longitudinally to obtain continuous micro-CT images at various levels. Subsequently, the three-dimensional structure of the femoral sample was reconstructed, and the trabecular bone and cortical bone areas were delineated based on specific criteria, with an analysis area set at 1 mm below the bone growth plate. CTan software was then utilized to quantitatively analyze the spatial structural parameters of the femoral trabeculae and cortical bone, while CTvol software was employed to establish and construct three-dimensional structural images of the trabeculae and cortical bone. Detailed procedures were conducted in accordance with previously published literature53.

Testing of tibia mechanical properties

The tibia was wrapped in moist gauze, and a three-point bending instrument (UniVert, Canada) was utilized to apply a bending force at a fixed displacement rate of 0.6 mm/min at the midpoint of the tibia until fracture. Finally, mechanical data were collected, and parameters such as maximum load and elastic modulus were calculated.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the femur and organ tissue

The femurs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 days, followed by treatment with a 10% EDTA decalcification solution, which was replaced every 2 days until the fragility of the bone disappeared. The decalcified femoral tissue, along with normal liver and kidney tissues, was rinsed with tap water and subsequently dehydrated using a series of alcohol concentrations. The femoral tissue was then soaked twice in xylene for 20 min per session, embedded in paraffin wax for 120 min, and sectioned into approximately 4.2 μm slices using a microtome. The sections were unfolded in warm water, retrieved, and placed onto slides. Following this, the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The stained sections were scanned using a digital sectioning scanner (Science, China). Furthermore, quantitative analysis of the number of osteoblasts distributed on the surface of trabecular bone was carried out as previously described54. Firstly, the surface area of the trabecular bone region was calculated using ImageJ software, and then the number of osteoblasts distributed on the surface of trabecular bone was counted. The final results are expressed as the number of osteoblasts contained per surface area of trabecular bone.

Preparation of Angelicae dahuricae Radix-medicated serum from rats

2-month-old healthy Sprague-Dawley (SD) female rats (200 ± 20 g, 6 rats in total) were randomly divided into control group and an AR treatment group (N = 3). The rats in the AR treatment group received an intragastric administration of AR (2 g·kg−1) for 7 days, while the control group rats were administered an equivalent volume of 0.5% CMC-Na for the same duration. One hour prior to sample collection, sodium pentobarbital at a mass concentration of 1.5% was injected intraperitoneally for anesthesia. Blood was collected from the abdominal aorta, with approximately 8 mL drawn from each rat. The samples were then centrifuged at room temperature at 3000 r·min−1 for 15 min, followed by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter membrane. Subsequently, the serum was incubated in a 56 °C water bath for 30 min to inactivate hormones, complements, antibodies, glycans, and other components. Finally, the serum was stored at −20 °C.

Culture of mouse osteoblast

MC3T3-E1 cells derived from mice were cultured in alpha Minimum Essential Medium (α-MEM) (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA). The medium was supplemented with 2.2 g·L−1 sodium bicarbonate, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biological Industries, 04-001-1 A, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel), and 1% penicillin (Amresco, 0242, Solon, OH) along with 1% streptomycin (Amresco, 0382, Solon, OH). The MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in a 24-well plate at 100% confluency, adhering to standard cell culture conditions in an incubator maintained at 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. The cells underwent treatment with osteogenic medium, which comprised 1% β-glycerophosphate (Sigma, G9422) and 1% ascorbic acid (Sigma, A7631). This osteogenic medium was replaced every 2 days for all groups and was supplemented with 10% rat serum either from a control or AR group.

Random positioning machine

A desktop random positioning machine (RPM) from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Center for Space Science and Applied Research was employed to simulate microgravity conditions55,56. MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded onto a glass culture plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells per square centimeter. Subsequently, the glass pieces were placed into RPM culture containers filled with induction medium (taking care to prevent the formation of growth bubbles). These culture containers were then installed in the RPM, which operated and rotated for 48 h at random speeds. In contrast, the ground control cells were maintained in the same incubator environment at 37 °C without rotation.

Alkaline phosphatase staining and alizarin red staining

Initially, the MC3T3-E1 cells were rinsed three times using PBS and subsequently treated with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. After another three rinses with PBS, the fixed cells were treated with the BCIP/NBT liquid substrate from the BCIP/NBT alkaline phosphatase kit (Beyotime, China) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Once the cells exhibited a color change to blue or purple, the staining process was halted by rinsing with ddH2O, and the staining results were imaged using a scanner.

For alizarin red staining (ARS), the MC3T3-E1 cells underwent the same washing and fixation procedures, followed by staining with a 0.5% solution of alizarin red (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at pH 4.2 for 15 min at room temperature. After the mineralization of the cell nodules, the staining process was concluded with three rinses in ddH2O, each lasting 5 min. Images of the mineralized nodules were captured using a scanner.

Alkaline phosphatase activity assay

Fully confluent MC3T3-E1 cells were induced using osteogenic medium. Subsequently, complete medium containing 10% AR serum was utilized to induce the MC3T3-E1 cells for 48 h. Triplicates were established for each group. The cultured MC3T3-E1 cells were then collected from the culture medium and washed three times with PBS. Subsequently, 100 μL of cell lysate and 1 μL of protease inhibitor were added to each group. Following 15 min of lysis on ice, the samples were resuspended and mixed thoroughly. The samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 g for 15 min prior to protein extraction. The concentrations of protein were quantitatively assessed using the BCA protein detection kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The activity of ALP proteins was measured using the ALP assay kit (Nanjing Jian cheng Technology Co. Ltd., China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Initially, the collected cells were placed on ice, and TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, MA, USA) was added to the stimulated cells for lysis and extraction of total RNA. The RNA samples were then converted into cDNA through reverse transcription using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Japan). Subsequently, gene expression analysis was performed using real-time PCR with the SYBR Premix Ex TaqII kit (TaKaRa, Japan) on the Thermal Cycler C-1000 Touch system (BIO-RAD CFX Manager, USA). The amplification results from all genetic tests were normalized against the internal reference gene, Gapdh. Data were analyzed and expressed as a fold change relative to the corresponding control group using the Ct method (2−ΔΔCt).

UPLC-MS/MS analysis of Angelicae dahuricae Radix medicated rat serum

To analyze the active ingredients of AR that were absorbed in blood, 50 μL of AR-medicated rat serum was vortexed for 10 seconds. Subsequently, 300 μL of 70% methanol internal standard extraction solution was added to the sample. The mixture was thoroughly mixed and vortexed for 3 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 r/min at 4 °C for 10 min. The sample was then placed in a − 20 °C refrigerator for 30 minutes. After this period, the sample was removed and centrifuged again at 12,000 r/min at 4 °C for 3 min. The supernatant was collected and transferred to the corresponding inner liner tube, and then injected into HPLC-MS/MS for analysis. The components in the AR-medicated serum were analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively using the Analyst 1.6.3 software, based on a self-built database (MWDB). (metware database, www.metware.cn).

Analysis of active compounds and targets in Angelicae dahuricae Radix anti-osteoporosis

The Traditional Chinese Medicine System Pharmacology Database, TCMSP (https://old.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php) was utilized to identify the chemical composition and corresponding targets of AR. Targets associated with osteoporosis were identified from the GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/). In addition, the relationship between compounds and targets was analyzed using Cytoscape 3.5.0 software. The regulatory molecular pathways involved in the targets of AR constituents were subsequently analyzed by integrating data from the KEGG database.

Evaluation of the safety of Angelicae dahuricae Radix in HLU and OVX mice

In order to evaluate the safety of AR in mice, following intraperitoneal injection of 1.5% pentobarbital sodium into mice, the blood was collected through cardiac puncture. The functions of the liver and kidneys were measured by blood biochemical analysis instrument (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). The indices of each organ were also estimated. The model mice were dissected, and the different organs were weighed.

Statistical analysis

The mean ± SD was used to express all numerical data. Two groups were analyzed through one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test using GraphPad Prism 8.3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA) software, P value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant in all instances (ns, not significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Responses