Antenatal Vitamin C differentially affects lung development in normally grown and growth restricted sheep

Introduction

Fetal lung development is under control of oxygen availability, hormones, molecular signaling (including growth factors) and structural/mechanical factors.1,2,3,4,5 Suboptimal intrauterine environments affect the development of the fetal lung, thereby influencing the risk of respiratory complications at birth and susceptibility to lung disease in later life.6,7,8,9 Understanding how pregnancy complications, such as fetal growth restriction, affect the developing lung and optimizing therapies to overcome the effects of suboptimal in utero environments to improve newborn outcomes is critically important.

Fetal growth restriction affects approximately 10% of pregnancies worldwide and most commonly occurs due to reduced oxygen and nutrient transport to the developing fetus.5,10 Fetal growth restriction has consequences on fetal growth and organ development that can have both direct and indirect effects on physiology leading to increased morbidity and mortality in early and later life.11,12,13 Altered oxygen availability and oxidative stress can have individual and synergistic effects on molecular and structural regulation of fetal lung development.6 In normal pregnancy, endogenous antioxidant defense mechanisms mature across late gestation in preparation for exposure to the relative hyperoxic air-breathing environment at birth.14,15,16,17 However, in pregnancies complicated by oxidative stress, insufficient fetal antioxidant defenses to scavenge the enhanced free radical production at the cellular level can lead to poorer infant outcomes.12,15,18,19,20,21

Heterogeneity in the effects of antioxidants in pregnancy is well known. For instance, in humans, deficiency of antioxidant Vitamin C during pregnancy is associated with increased preterm premature rupture of the membranes.22,23 Conversely, maternal supplementation with the antioxidants Vitamins C and E, to reduce the risk of pre-eclampsia, increased the risk of babies being born small24 and had effects on markers of oxidative stress and placental function.25 Follow up of these babies also demonstrated no longer term benefits on asthma at 2 years of age.26 In hypoxic pregnancy in sheep and rats, maternal treatment with Vitamin C protected against fetal growth restriction and the programming of cardiovascular dysfunction in the adult offspring.12,27,28,29,30 Clinically, antenatal Vitamin C treatment to pregnant smokers improved lung function in newborns (ratio of the time to peak tidal expiratory flow to expiratory time [TPTEF:TE] and passive respiratory compliance per kilogram,31) increased forced expiratory flow at 3 and 12 months of age,32,33 and reduced wheeze at 1 year of age. More recently, antenatal Vitamin C supplementation has been shown to ameliorate changes associated with maternal smoking in placental DNA methylation and gene expression of pathways associated with placental function and lung function/wheeze.34 This diversity in effects is not unique to antioxidant treatment in pregnancy, with many documented differences in the effects of other pharmacological interventions in the healthy versus growth-restricted fetus, including maternal treatment with antenatal glucocorticoids, sildenafil and melatonin.7,12,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 Therefore, there is a clear fundamental need for pre-clinical investigation of potential therapeutics in models of complicated pregnancy with heterogeneous causes to ensure that interventions have the desired molecular effects and do not cause unintended harm to individuals.

While clinical studies have provided insights into the heterogeneous incidence and risk of growth restricted newborns experiencing respiratory complications,7 they are unable to provide detailed mechanistic insights into factors regulating altered lung development. We have previously demonstrated that exposure to chronic fetal hypoxia44 and antenatal antioxidant treatment in normal pregnancy45 both have significant effects on molecular regulation of fetal lung maturation. Specifically, exposure to maternal chronic hypoxia increased expression of genes regulating lung liquid reabsorption (sodium and water movement), surfactant maturation and lipid transport and hypoxia signaling.44 Antenatal Vitamin C exposure in normal pregnancy increased fetal lung gene expression of antioxidant enzymes, hypoxia signaling, sodium movement, surfactant maturation and airway remodeling.45 In this study, we have compared the effects of maternal treatment with antioxidant Vitamin C on lung development between the normoxic normally grown fetus and the hypoxic growth restricted fetus. The study was carried out in sheep, as sheep and humans share similar prenatal milestones of lung development.46 We used a dosing regimen of Vitamin C previously validated to protect against oxidative stress in hypoxic pregnancy in this species.27 We focused on molecular pathways involved in normal fetal lung development, including surfactant maturation, lung liquid movement, glucocorticoid signaling and hypoxia signaling.

Methods

All procedures were approved by the University of Cambridge Ethical Review Board and were performed in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. In this study, 34 pregnant Welsh mountain ewes carrying singleton pregnancies were used.

Surgery and experimental protocol

At 100 ± 1 days gestation (term, ~145 d), all ewes underwent a sterile laparotomy under general anesthesia (1.5–2.0% isofluorane in 60:40 O2:N2O) to determine fetal sex and catheterization of the maternal femoral artery and vein, as previously described.27,47,48 To control for sex differences only male fetuses were included in this study. Female fetuses were assigned to a postnatal study49. At 105 d gestation (when the fetal lung is in the canalicular phase of development; equivalent to ~21 weeks human gestation, term = 40 weeks),50,51 ewes were randomly assigned to one of four experimental groups. Pregnant ewes assigned to the hypoxic group (n = 17) were housed in bespoke isobaric hypoxic chambers (Telstar Ace, Dewsbury, West Yorkshire, UK) from 103 d gestation under normoxic conditions and exposed to ~10% O2 from 105 d gestation by altering the incoming inspirate mixture as previously established.48 Ewes allocated to the normoxic group (n = 17) remained housed in individual floor pens of the same size as the hypoxic chambers and with access to the same nutritional regimen for the duration of the experimental protocol.27 While the Control ewes were not housed in the same chambers as the hypoxic group, we controlled for as many factors as possible, including the pen floor surface area, humidity, temperature, noise levels and the feeding regimen.48 Critically, animals in both groups were always able to see other sheep, thereby minimizing stress. Within the hypoxic chambers, the inspirate air mixture was passed via silencers able to reduce noise levels within the hypoxic chamber laboratory (76 dB(A)) and inside each chamber (63 dB(A)) to values lower than those necessary to abide by the Control of Noise at Work Regulations. This not only complied with human health and safety and animal welfare regulations but also provided a tranquil environment for the animal inside each chamber. All chambers were equipped with an electronic automatic humidity cool steam injection system (1100-03239 HS-SINF Masalles, Barcelona, Spain) to ensure appropriate humidity in the inspirate (55 ± 10%). Ambient PO2, PCO2, humidity and temperature within each chamber were monitored via sensors, displayed and values recorded continuously via the Trends Building Management System of the University of Cambridge through a secure Redcare intranet. In this way, the percentage of oxygen in the isolators could be controlled with precision continuously over long periods of time, while minimizing maternal stress.48 Measurements of stress hormones in maternal plasma during chronic hypoxia confirmed lack of any change from baseline.48 This model of maternal chronic hypoxia also does not affect maternal food intake.48

At 105 d gestation, ewes were further split into 2 groups; receiving either a daily bolus (between 09:00 and 10:00) of intravenous Saline (0.6 mL/kg; Normoxic + Saline, NS, n = 8; Hypoxic + Saline, HS, n = 8) or Vitamin C dissolved in saline (200 mg/kg i.v. daily Ascorbate; A-5960; Sigma Chemicals, UK; 1.14 mmol/kg/day dissolved in 0.6 ml/kg saline; Normoxic + Vitamin C, NVC, n = 9; Hypoxic + Vitamin C, HVC, n = 9) from 105–135 d gestation. Vitamin C was chosen for administration in this study due to it being a commonly used water-soluble antioxidant supplement that can cross the placenta.27,52 We have previously established powerful antioxidant protection in the offspring by Vitamin C in several species, including the sheep.12,27,28,29,30,53,54,55 While Vitamin C can be easily administered both orally and daily in humans, the maternal i.v. route was chosen in sheep in this study to better control delivery into the maternal circulation. The rationale for a higher dose of Vitamin C used in this study versus that used in clinical trial (14.3 mg/kg/day24) was derived from previous studies in sheep pregnancy in our laboratory, which achieved elevations in circulating ascorbate concentrations within the required range for Vitamin C to compete effectively in vivo with nitric oxide in ovine pregnancy.53,56,57 To characterize effects in this model, maternal blood samples were taken at baseline (before infusion at 09:00–10:00 on 104–105 d gestation) and post treatment samples were taken 24 h after the first bolus at 106 d and then every 5 days thereafter (09:00–10:00) to measure plasma ascorbate concentration. Maternal Vitamin C treatment in both control and hypoxic ewes produced similar increments from baseline in maternal plasma Vitamin C, doubling and sustaining the circulating concentration over the period of treatment from 105 to 135 days of gestation.27 This dose effect is similar to the effect of Vitamin C treatment in human clinical trials, which also lead to a doubling of ascorbate concentrations in maternal plasma.24 We have previously demonstrated that this model of maternal chronic hypoxia44 and chronic Vitamin C exposure in normal pregnancy45 confers significant effects molecular regulation of fetal lung development.

Post-mortem and sample collection

Fetuses were exposed to either maternal normoxia or chronic hypoxia from 105 d gestation until postmortem. Fetuses were evaluated near-term at 138 d gestation when the lung is in the alveolar stage of development similar to human late preterm birth (36–37 week of gestation; term = 40 weeks50,51). Immediately prior to euthanasia, a maternal blood sample was collected for analysis of plasma Vitamin C concentration. All ewes and their fetuses were euthanized by overdose of sodium pentobarbitone (0.4 mL/kg, slow intravenous administration, Pentoject; Animal Ltd, York, UK) and fetuses were delivered by hysterotomy. A fetal umbilical arterial blood sample was taken at post-mortem for measurement of plasma Vitamin C concentration. Fetal body and organ weights were recorded. A piece of left fetal lung tissue was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for gene and protein expression analysis. A section of right fetal lung tissue was immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed to paraffin for immunohistochemical analysis.

The tissues generated in this study were part of a program of work designed with the primary objective of investigating cardiovascular physiology.27 This study used the tissues generated to address additional important scientific questions retrospectively, thereby making best use of the valuable experimental material. This scientific approach is strongly recommended by the UK Home Office 3 R principle of Replacement, Reduction and Refinement designed to ensure more humane animal research.58 Consequently, no developmental trajectory time points, lung tissue stereological analysis or prospective functional respiratory outcomes were performed.

Maternal and fetal plasma Vitamin C analysis

Plasma concentrations of Vitamin C were measured by a fluorimetric technique using a centrifugal analyzer with a fluorescence attachment, according to the method of Vuilleumier and Keck,59 in collaboration with the Core Biochemical Assay Laboratory, Cambridge, UK as previously described.27,45

Quantification of fetal lung mRNA expression

RNA was extracted and cDNA synthesized from fetal lung tissue samples ( ~50 mg; NS, n = 8; HS, n = 8; NVC, n = 9; HVC, n = 9) as previously described45,60,61,62 and following the MIQE guidelines.63 The expression of target genes regulating surfactant maturation, lung liquid secretion and reabsorption (regulated by chloride, sodium and water transport across the pulmonary epithelium), glucocorticoid signaling and hypoxia signaling6,37,64 were measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR; Table 1), as previously described.45,60,61,62,65,66 The abundance of each transcript relative to the abundance of stable reference genes (beta-actin, peptidylprolyl isomerase, tyrosine 3-monooxygenase) was calculated using DataAssist 3.0 analysis software and is expressed as mRNA mean normalized expression (MNE) ± SD.45,60,61,62

Quantification of fetal lung protein expression

Protein was extracted by sonication of fetal lung tissue ( ~100 mg, NS n = 6, NVC n = 7, HS n = 7, NVC n = 7;45,61,67,68). Protein content was determined by a MicroBCA Protein Assay Kit (PIERCE, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, Illinois) and samples were then diluted to the same concentration so that a consistent volume is loaded into each well on the Western blot. Primary antibodies of interest were SP-B (1:1000, in 5% BSA in TBS-T, #WRAB-48604, Seven Hills Bioreagents; 8 kDa band); ENAC-β (1:1000, in 5% BSA in TBS-T, #PA5-77817, Invitrogen; 87 kDa band); Na+-K+-ATPase-α1 (1:1000 in 5% BSA in TBS-T, #MA3-929, Invitrogen; 110 kDa), Na+-K+-ATPase-β1 (1:1000 in 5% BSA in TBS-T, #MA3-930, Thermofisher; 50 kDa band); 11βHSD-2 (1:1000, in 5% BSA in TBS-T, #10004303, Cayman Chemical; 44 kDa band), GLUT-1 (1:1000, in 5% BSA in TBS-T, #CBL242, Chemicon Millipore; 46 kDa band). The primary antibodies were chosen based on genes that changed in response to antenatal Vitamin C administration in the fetal lung to determine if the transcriptional changes observed translated into protein abundance differences. Following incubation with the primary antibody, the blots were washed and incubated with the relevant species of Horse Radish Peroxidase labeled secondary IgG antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Enhanced chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Australia) was used to detect the blots. The Western blot was imaged using ImageQuant LAS4000 and the protein abundance was quantified by densitometry using Image quant software (GE Healthcare, Victoria, Australia). Total target protein abundance was then normalized to total protein (Ponceau S) or to a reference protein, β-actin (1:10,000 in 5% BSA in TBS-T, ATCB HRP conjugate, #4967, Cell Signaling Technology; 42 kDa band), β-tubulin (1:10,000 in 5% BSA in TBS-T, Beta TUBULIN (9F3) HRP conjugate, #5346, Cell Signaling Technology; 55 kDa band) or COX1V (3E11) (1:10,000 in 5% BSA in TBS-T, COX1V (3E11) HRP conjugate, #5247 P, Cell Signaling Technology; 17 kDa band).

Quantification of surfactant producing cells within lung tissue

To determine the effect of chronic fetal hypoxia and antenatal Vitamin C administration on the surfactant-producing capacity of the lung at the structural level, immunohistochemistry was performed (NS = 8; NVC = 9; HS = 8; HVC = 9) using a rabbit anti-human mature surfactant protein B (SP-B) antibody (1:500, WRAB-48604, Seven Hills Bioreagents, Ohio), as previously described.44,45 Sections were examined using Visiopharm new Computer Assisted Stereological Toolbox (NewCAST) software (Visiopharm, Hoersholm, Denmark) and point counting was used to determine the numerical density of SP-B positive cells present in the alveolar epithelium of lung tissue, as previously described.44,45,69

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v8). All data were evaluated for outliers ± 2 SD from the mean for each treatment group (only 1 round of outlier removal was performed). Data in figures and table are presented as Log2 fold change of mean normalized expression ± SD to demonstrate the effect of Vitamin C compared to respective saline Control group for both Normoxic (n = 9; NVC vs mean of NS group) and Hypoxic (n = 9; HVC vs mean of HS group) fetuses.

All data were checked for normality and if normally distributed data were compared using the Student’s t-test for unpaired data and if not normally distributed data were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Statistical analysis was undertaken firstly to determine if there was a significant effect of Vitamin C within each treatment group (i.e. NVC vs NS group and HVC vs HS group) and secondly to determine if there was a significant difference between the effect of antenatal Vitamin C between Normoxic and Hypoxic fetuses. For all comparisons, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Plasma Vitamin C and fetal growth

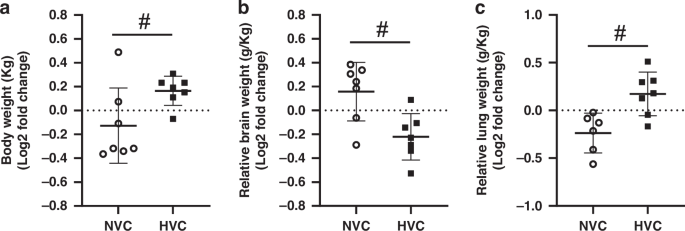

Maternal plasma Vitamin C levels did not differ between groups at baseline (105 d gestation; N: 38.0 ± 3.9 µmol/L; H: 36.2 ± 3.1 µmol/L; HVC: 44.1 ± 4.5 µmol/L; NVC: 43.8 ± 3.3 µmol/L). Maternal treatment with Vitamin C significantly increased plasma Vitamin C concentration to similar levels in samples taken just prior to post-mortem in the treated Normoxic (81.4 ± 12.8 µmol/L) and Hypoxic pregnant ewes (71.6 ± 6.0 µmol/L), approximately doubling basal levels (P < 0.05). Plasma levels of Vitamin C measured in the sample taken from the fetal umbilical artery at post-mortem were also similarly elevated in fetuses from Normoxic and Hypoxic ewes treated with Vitamin C compared to those from pregnancies treated with saline alone (N: 20.2 ± 1.2 µmol/L; H: 22.3 ± 3.8 µmol/L; NVC: 30.1 ± 1.4 µmol/L; HVC: 33.1 ± 1.2 µmol/L; P < 0.05). There was no significant effect of antenatal Vitamin C on fetal body, relative brain weight or relative lung weight in both normally grown and growth restricted fetuses (Fig. 1a–c). However, there was, a significant effect of exposure to maternal chronic hypoxia, which is driven by the induction of asymmetric fetal growth restriction compared to normally growth fetuses (Fig. 1a–c).

Fetal body weight a, relative brain weight b and relative lung weight c. Data presented as Log2 fold change (compared to respective saline group) mean ± SD in the Normoxic Vitamin C (NVC; white circles, n = 9) and Hypoxic Vitamin C (HVC; black squares; n = 9) fetal lung. All data were evaluated for outliers ± 2 SD from the mean for each treatment group. Positive or negative mean values indicate induction or repression of gene expression, respectively. #P < 0.05; significant difference between Vitamin C effectiveness in the normally grown vs. growth restricted fetal lung (i.e. NVC vs. HVC).

Regulation of surfactant maturation

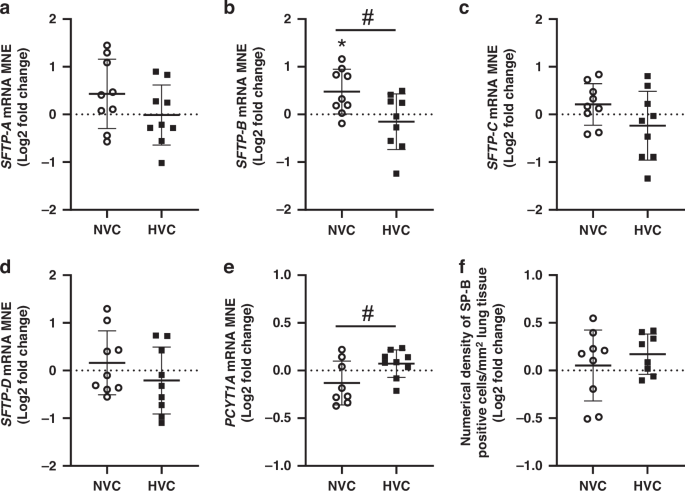

There was a significant effect of antenatal Vitamin C treatment increasing SFTP-B mRNA expression in the lung of Normoxic but not Hypoxic fetuses (Fig. 2b). There was a differential effect of antenatal Vitamin C treatment between Normoxic and Hypoxic fetuses, with increased expression of SFTP-B (Fig. 2b) and decreased surfactant phospholipid marker PCYT1A (Fig. 2e) in the lung of Normoxic compared to Hypoxic fetuses. There was no significant effect of antenatal Vitamin C treatment on expression of SFTP-A, SFTP-C and SFTP-D or numerical density of SP-B positive cells in the alveolar epithelium between Normoxic and Hypoxic fetuses (Fig. 2a, c, d, f).

Mean normalized gene expression (MNE) of surfactant protein (SFTP)-A a, -B b, -C c, -D d and phosphate cytidylyl transferase 1, choline, alpha (PCYT1A; e). Surfactant protein-producing capacity of the lung was determined by quantitating the numerical density of SP-B positive cells in the alveolar epithelium of lung tissue f. Data presented as Log2 fold change (compared to respective saline group) mean ± SD in the Normoxic Vitamin C (NVC; white circles, n = 9) and Hypoxic Vitamin C (HVC; black squares; n = 9) fetal lung. All data were evaluated for outliers ± 2 SD from the mean for each treatment group. Positive or negative mean values indicate induction or repression of gene expression, respectively. *P < 0.05; compared to respective control group, i.e. N vs. NVC or H vs. HVC. #P < 0.05; significant difference between Vitamin C effectiveness in the normally grown vs growth-restricted fetal lung (i.e NVC vs. HVC).

Expression of genes regulating fetal lung liquid movement

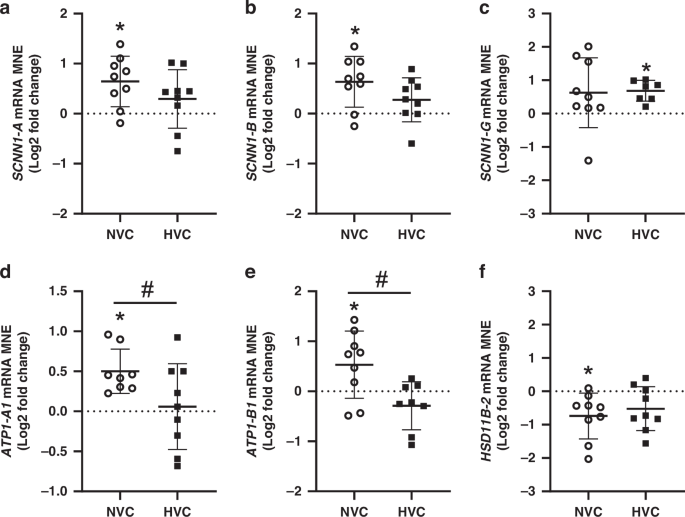

There was a significant effect of antenatal Vitamin C treatment increasing SCNN1-A, SCNN1-B, ATP1-A1 and ATP1-B1 in the lung of Normoxic but not Hypoxic fetuses (Fig. 3a, b, d, e). Conversely, antenatal Vitamin C treatment significantly increased expression of SCNN1-G in the lung of Hypoxic, but not Normoxic fetuses (Fig. 3c). There was a differential effect of antenatal Vitamin C treatment on expression of ATP1-A1 and ATP1-B1 between Normoxic and Hypoxic fetuses (Fig. 3d, e). In contrast, there was no effect of antenatal Vitamin C treatment on the expression of genes regulating chloride movement (CFTR or CLCN2) or water movement (AQP-1, AQP-3, AQP-4 or AQP-5) in the lung of Normoxic and Hypoxic fetuses (Table 2).

Epithelial sodium channel (SCNN1)-A a, -B b and -G c subunits, sodium potassium ATPase-A1 (ATP1-A1, d) sodium potassium ATPase-B1 (ATP1-B1, e) and glucocorticoid activating enzyme HSD11B-2 f. Gene data presented as Log2 fold change (compared to respective saline group) mean normalized expression (MNE) ± SD in the Normoxic Vitamin C (NVC; white circles, n = 9) and Hypoxic Vitamin C (HVC; black squares; n = 9) fetal lung. All data were evaluated for outliers ± 2 SD from the mean for each treatment group. Positive or negative mean values indicate induction or repression of gene expression, respectively. *P < 0.05; compared to respective control group, i.e. N vs. NVC or H vs. HVC. #P < 0.05; significant difference between Vitamin C effectiveness in the normally grown vs growth-restricted fetal lung (i.e NVC vs. HVC).

Expression of genes regulating glucocorticoid signaling

There was a significant effect of antenatal Vitamin C treatment decreasing the mRNA expression of glucocorticoid deactivating enzyme HSD11β-2 in the lung of Normoxic but not Hypoxic fetuses (Fig. 3f). In contrast, there was no significant effect of antenatal Vitamin C on the mRNA expression of the glucocorticoid activating enzyme HSD11β-1 or the receptors for downstream glucocorticoid signaling (NR3C1 and NR3C2) or on the glucocorticoid responsive gene NKX2-1 in the lung of Normoxic or Hypoxic fetuses or the magnitude of effect between them (Table 2).

Expression of genes regulating hypoxia signaling

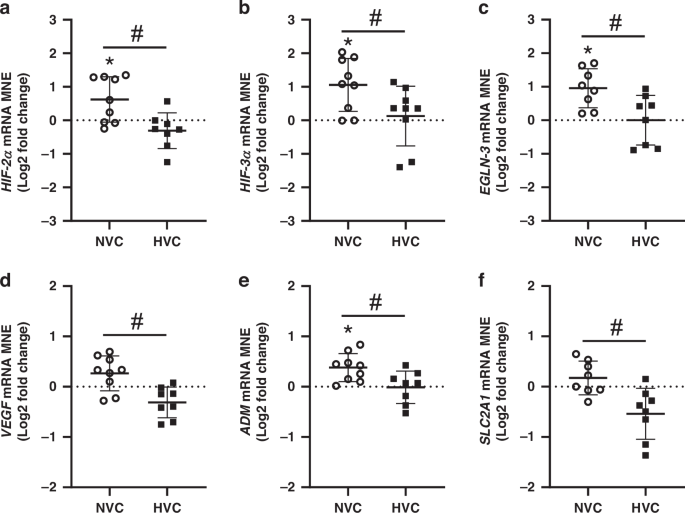

There was a significant effect of antenatal Vitamin C treatment upregulating the expression of genes regulating hypoxia signaling (HIF-2α, HIF-3α, EGLN-3) and the hypoxia responsive gene ADM in the lung of Normoxic but not Hypoxic fetuses (Fig. 4a–c, e). There was a significant differential response to antenatal Vitamin C in the lung expression of HIF-2α, HIF-3α, EGLN-3, VEGF, ADM and SLC2A1 between Normoxic and Hypoxic fetuses (Fig. 4). Conversely, there was no significant effect of antenatal Vitamin C or exposure to Hypoxia on expression of HIF-1α, HIF-1β, EGLN-1, EGLN-2 or KDM3A (Table 2).

Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-2α a and -3α b subunits, prolyl hydroxylase domain (EGLN)-3 c and hypoxia-responsive genes vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, d); adrenomedullin (ADM, e) and facilitated glucose transporter 1 (SLC2A1, f). Gene data presented as Log2 fold change (compared to respective saline group) mean normalized expression (MNE) ± SD in the Normoxic Vitamin C (NVC; white circles, n = 9) and Hypoxic Vitamin C (HVC; black squares; n = 9) fetal lung. All data were evaluated for outliers ± 2 SD from the mean for each treatment group. Positive or negative mean values indicate induction or repression of gene expression, respectively. *P < 0.05; compared to respective control group, i.e. N vs. NVC or H vs. HVC. #P < 0.05; significant difference between Vitamin C effectiveness in the normally grown vs growth-restricted fetal lung (i.e NVC vs. HVC).

Protein expression of genes in lung signaling pathways that changed in response to antenatal Vitamin C treatment

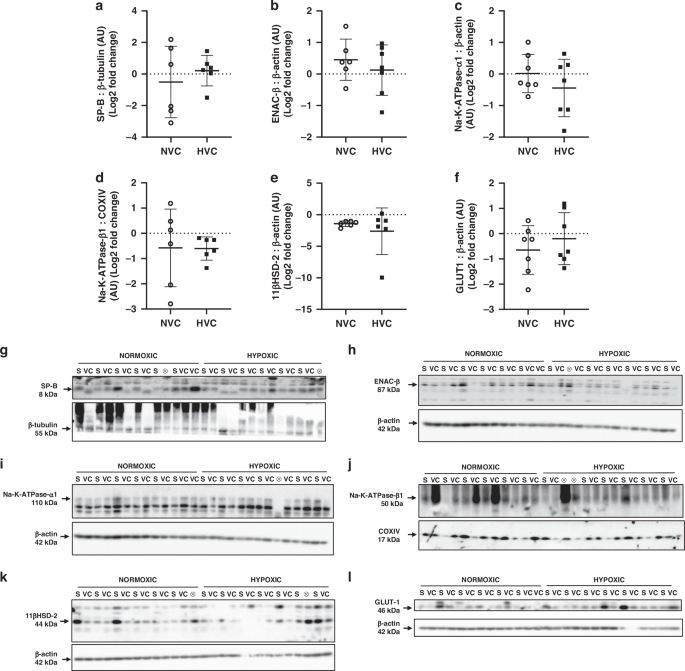

To investigate if there were effects on translation potential in the fetal lung, we investigated the protein expression of a panel of genes from signaling pathways that changed in response to antenatal Vitamin C exposure. There was no significant effect of antenatal Vitamin C treatment or hypoxia on the lung protein expression of SP-B, factors regulating sodium movement (ENAC-ß, Na-K-ATPase-α1, Na-K-ATPase-ß1), glucocorticoid activity (11ßHSD-2) or on the hypoxia-responsive factor GLUT-1 (Fig. 5).

Data presented as normalized protein expression in arbitrary units (AU) for SP-B (a; 8 kDa band), ENAC-ß (b; 87 kDa band), Na-K-ATPase-α1 (c; 110 kDa band), Na-K-ATPase-ß1 (d; 50 kDa band), 11ßHSD-2 (e; 44 kDa band), GLUT-1 (f; 46 kDa band). Western blot images represent target protein (upper panel) and reference protein (lower panel) for fetuses in normoxic + saline (NS), normoxic + Vitamin C (NVC), hypoxic + saline (HS) and hypoxic + Vitamin C (HVC) fetuses. ⊗ = Outliers (all data were evaluated for outliers ± 2 standard deviations from mean of each treatment group) not included in analysis. Beta actin (ß-actin; h, i, k, l; 42 kDa band), Cytochrome oxidase IV (COXIV; j; 17 kDa band), and beta-tubulin (ß-tubulin; g; 55 kDa band) are obtained from the same gel. Positive or negative mean values indicate induction or repression of gene expression, respectively. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

The data show a differential effect of maternal Vitamin C treatment on regulation of genes involved in surfactant maturation, sodium movement and hypoxia signaling between the normoxic normally grown sheep fetus and the chronically hypoxic growth restricted sheep fetus. We demonstrate variability in the magnitude, and in some cases the direction, of the effects of maternal treatment with Vitamin C on the gene expression of pathways involved in lung development between the Normoxic and Hypoxic sheep fetus.

In normoxic fetal sheep, maternal treatment with Vitamin C during late gestation significantly increases the lung gene expression of factors regulating surfactant production, sodium transport (key regulator of lung liquid movement in fetal life), glucocorticoid availability and hypoxia signaling45 (see summary in Table 3). Here, we show that maternal treatment with Vitamin C in the hypoxic growth restricted sheep fetus compared to the normoxic sheep fetus has very limited effects in the magnitude (except for an increase in SCNN1-G expression) and, in some cases, differential effects in the direction of changes in gene expression pathways involved in lung development compared to the normally grown fetus (see summary in Table 3). Using this model of maternal chronic hypoxia for a month in late gestation to induce fetal growth restriction,27 we have also reported that the chronically hypoxic sheep fetus compared to the normoxic sheep fetus in untreated pregnancies shows increased expression of molecular markers regulating surfactant maturation and lipid transport, lung liquid movement (markers of sodium and water movement) and hypoxia signaling in the fetal lung44 (see summary in Table 3). Therefore, rather than signifying resistance to the antenatal Vitamin C treatment, the most likely explanation for a lack or very limited effect of maternal treatment with Vitamin C in the hypoxic fetus in this study is that molecular signaling pathways in the lung are maximally upregulated in response to the chronic hypoxic insult in this model; thus, added exposure to Vitamin C is unable to upregulate the system further. Indeed, this hypothesis is supported by the findings from this study and our previous studies whereby molecular marker SFTP-B expression was increased by 53% in response to maternal chronic hypoxia (0.85 ± 0.22 NS vs. 1.30 ± 0.44 HS MNE; P = 0.02) and increased 46% in response to antenatal Vitamin C in normoxic pregnancy (0.85 ± 0.22 NS vs. 1.24 ± 0.40 NVC MNE; P = 0.03). However, in the lung of the chronically hypoxic fetus exposed to Vitamin C, there was a similar increase from Control values (47%; 0.85 ± 0.22 NS vs. 1.25 ± 0.46 HVC MNE; P = 0.04), but when compared to the lung exposure to maternal chronic hypoxia alone there was only a 4% difference (1.30 ± 0.44 HS vs 1.25 ± 0.45 HVC MNE; P = 0.83). Hence this study provides evidence that there is no synergistic upregulation of surfactant markers in the lung of fetuses exposed to both maternal chronic hypoxia and antenatal Vitamin C, supporting a maximal upregulation of the system in response to the chronic hypoxia insult alone. In addition, this study highlights that while antenatal Vitamin C exposure has differential effects on molecular regulation of the lung in both normally grown and growth-restricted fetuses, in this cohort there was no effect of Vitamin C exposure on fetal body, relative lung weight, or the number of SP-B producing cells in the alveolar epithelium of fetal lung tissue.

The analysis in this study highlights a significant difference between responsiveness of the normally grown and growth-restricted fetal lung to antenatal Vitamin C treatment in key molecular developmental pathways. There was a differential response to Vitamin C with higher gene expression of SFTP-B, ATP1A1, ATP1B1, HIF-2α, HIF-3α, EGLN-3, VEGF, ADM, SLC2A1 and lower gene expression of PCYT1A in the lung of the normally grown fetus compared with the growth restricted fetal lung. It is clear that exposure to a single insult in this sheep model, either maternal chronic hypoxia44 or antenatal Vitamin C administration in healthy pregnancy,45 can promote upregulation of genes regulating fetal lung development, but synergistic exposure to both insults did not confer further benefit (see summary in Table 3). We have previously shown benefits of maternal chronic hypoxia (decreasing expression of prooxidant maker NOX-4 and increasing antioxidant marker CAT44) and antenatal Vitamin C treatment in normoxic pregnancy (increasing expression of antioxidant marker SOD-145). However, due to lack of sample availability, in this study we were unable to investigate the impact of exposure to maternal chronic hypoxia and antenatal Vitamin C treatment on molecular regulation of oxidative stress in the fetal lung. While there were significant effects of either exposure to antenatal chronic hypoxia or Vitamin C on gene expression in the fetal lung in this study, there were no differences in the expression of a panel of proteins involved in surfactant maturation, sodium movement, glucocorticoid availability, and hypoxia-responsive proteins. Therefore, the increase in gene expression may serve as a local reservoir of molecular regulators that can be drawn upon in response to developmental challenges, such as acute hypoxic challenge or preterm exposure to the air-breathing environment at birth. Conversely, while beyond the scope of this study, there may be epigenetic posttranscriptional changes programmed by exposure to maternal chronic hypoxia on translation of genes in these signaling pathways. Future studies generating new tissue cohorts are required to specifically investigate these mechanisms.

Table 3 provides a direct comparison between studies investigating gene expression markers of fetal lung development using this sheep model of exposure to maternal chronic hypoxia and/or antenatal Vitamin C. Of interest, there is considerable overlap in the expression of genes that are upregulated in the fetal lung by Vitamin C treatment in normoxic pregnancy (10 genes; those regulating hypoxia signaling and feedback = HIF-2α, HIF-3α, EGLN-3, ADM; glucocorticoid availability = HSD11B-2; sodium movement = SCNN1-A, SCNN1-B, ATP1-A1, ATP1-B1; and surfactant maturation = SFTP-B45) and in the expression of genes that are upregulated in the fetal lung by exposure to chronic hypoxia alone in untreated pregnancy (10 genes; those regulating hypoxia signaling and feedback = HIF-3α, EGLN-3, KDM3A, SLC2A1; sodium movement = SCNN1-B, ATP1-A1, ATP1-B1; water movement = AQP4; and surfactant maturation = SFTP-B, SFTP-D44). However, there are several changes within these signaling pathways that are unique to either exposure to chronic hypoxia in untreated pregnancy or treatment with Vitamin C in normoxic pregnancy. Therefore, exposure of the fetal lung to different stimuli in normoxic and hypoxic fetal sheep can generate individual molecular signatures regulating fetal lung maturation.

While there is limited understanding of the effect of antenatal Vitamin C on the fetal lung, there is further evidence of the complex direct and indirect regulatory role and interaction between growth restriction, oxidative stress and antenatal antioxidants in postnatal life. In a sheep model of growth restriction induced by single uterine umbilical artery ligation at 105 d gestation, chronically hypoxic growth-restricted lambs (at 24 h of age) had altered structural lung development but daily antioxidant melatonin treatment did not protect against this.70 In a further study, antenatal melatonin treatment for the last third of gestation modulated pulmonary responsiveness, antioxidant capacity and prooxidant status in the lung of chronically hypoxic fetal sheep at 12 days after birth.40 These studies provide insights into the differential effects of growth restriction models on the postnatal lung and considerations for the role of antenatal antioxidants in developmental programming of responsiveness to hypoxic/hyperoxic challenges in postnatal life. Indeed, at the cellular level, a differential effect of chronic or intermittent hypoxia-hyperoxia on mitochondrial structure and function in fetal airway smooth muscle cells highlights the importance of physiological balance between overloading the system with antioxidants and removing reactive oxygen species below physiological levels.71

There is a critical need to investigate candidate antenatal interventions extensively in pre-clinical studies taking into account obstetric subpopulations prior to therapeutic use clinically to avoid unintended consequences on the fetus and organ systems as a result of heterogeneous causes of pregnancy complications.5,12,72,73,74 In a model of intrauterine inflammation in a premature mouse model, antenatal melatonin normalized markers of inflammation, SP-B expression in the fetal lung (E18) and lung structure in the neonatal lung (d1) and showed visual differences in magnitude of effect between Control and mice with intrauterine inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide exposure.75 When investigating antenatal therapeutics, it is also important to consider interaction with other commonly administered antenatal treatments, for example exposure to antenatal glucocorticoids in extremely preterm newborns has some antioxidant effects, reducing postnatal oxidative stress and endogenous antioxidant activity with a greater effect observed in females.76

While our findings provide further mechanistic insights into the role of antenatal Vitamin C on regulation of lung development of the normally grown and growth restricted sheep fetus, there are some important limitations of this study. First, while we controlled for as many factors as possible (including, pen floor surface area, humidity, temperature, noise levels, feeding regimen, remote monitoring systems, mitigating exposure to excessive noise and visibility of other sheep to reduce stress), Control ewes were housed in floor pens while the animals exposed to hypoxia were housed in the bespoke chambers. However, we believe this did not have a significant effect on maternal stress between groups, evidenced by no change from baseline in maternal stress hormones or food intake.48

Secondly, while the dose of Vitamin C administered to ewes in this model to achieve antioxidant effects in the fetus is significantly higher than the dose used in human clinical trials, the relative dose effect resulting in doubling of maternal plasma ascorbate concentrations is consistent with human clinical studies.24,27,53 While the values achieved for ascorbate concentrations are lower in the fetus than in the mother, little is known about the transport of Vitamin C in the ovine placenta or the factors affecting it. This is an area worthy of deeper investigation and consideration towards clinically applicable and translatable outcomes. Particularly as when investigating interventions to overcome the effect of oxidative stress in pregnancies complicated by growth restriction, poor placental development and/or function will likely contribute to heterogeneity in transport and therefore impact on responsiveness at the organ level.

Thirdly, as the tissues generated were part of a program of work designed with the primary objective of investigating cardiovascular physiology,27,48 only molecular studies were able to be undertaken and as such we do not know the lung structural and functional effects on the transition to air-breathing or lung function. As such we are unable to compare fetal lung function outcomes after antenatal Vitamin C exposure with the existing clinical studies during infancy. Fourth, only male fetuses were used in this study (females were assigned to a postnatal study) so we are unable to interrogate potential sex differences. Finally, this study has focused on characterizing antenatal Vitamin C exposure in one model of fetal growth restriction induced by maternal isobaric hypoxia and it is well documented that effects of chronic hypoxemia are regulated by the timing, severity and duration of the insult.5,6,10 From a mechanistic understanding, it would be interesting to investigate if the effect of antenatal Vitamin C exposure would have a more significant effect at the molecular level in the fetal lung in a model of early growth restriction such as placental restriction induced by uterine carunclectomy or single uterine artery ligation, which in itself downregulates molecular markers of lung maturation.6,10 Such studies would help elucidate further if the capacity for Vitamin C to maximally upregulate molecular signaling in the fetal lung is different between hypoxic fetuses produced by different types of adverse intrauterine conditions.

In summary, the data presented in this study provide molecular insights into the heterogeneity of the lung’s response to antenatal Vitamin C treatment in fetuses from normal pregnancies and those from pregnancies complicated by chronic hypoxia and fetal growth restriction. Specifically, the effectiveness of antenatal intervention with Vitamin C in complicated pregnancy may depend on the timing, severity and duration of the suboptimal gestational condition. Variable molecular responses to antenatal interventions in normally grown and growth restricted fetuses highlight the need for further investigation of antenatal interventions in preclinical animal models of fetuses of compromised pregnancy prior to human use to ensure benefits of effective therapeutic intervention outweighs potential harm.

Data avaliability

All data supporting the results are presented in the manuscript.

Responses