Anti-obesity effect of irreversible MAO-B inhibitors in patients with Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

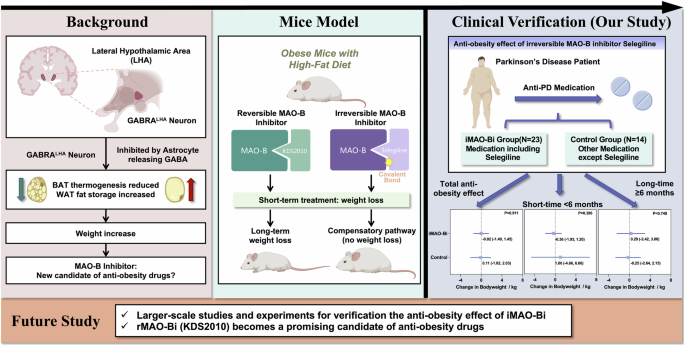

Obesity is related to chronic over-nutrition and imbalanced energy expenditure, and neuron activities in the hypothalamic area may have a causal role in the pathogenesis of obesity [1, 2]. Moonsun et al. recently published a report on GABRA5-positive neurons in the lateral hypothalamic area as a new therapeutic target for obesity, suggesting a potential anti-obesity effect by inhibiting GABA with monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors (MAO-Bi) [3]. Among MAO-Bi, irreversible MAO-B inhibitors (iMAO-Bi), e.g., selegiline, have been widely used in treating Parkinson’s disease (PD) and have been researched in treating other neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and stroke [3,4,5]. According to a recent study by Park et al. [4], iMAO-Bi may destroy the MAO-B enzyme and further activate compensatory gene expression. In contrast, reversible MAO-Bi (rMAO-Bi) can competitively occupy the active site of MAO-B enzyme, resulting in intact MAO-B enzyme without activating compensatory gene expression. These animal studies showed that Selegiline only had a short-term reduction in the body weight of animal models. However, the effect of iMAO-Bi has not been thoroughly studied in humans.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to investigate the anti-obesity effect of iMAO-Bi among PD patients admitted to the neurology department in Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) from 2018 to 2023. The cohort was collected by following the inclusion and exclusion criteria: we included the patients (1) firstly diagnosed as PD at PUMCH; (2) hospitalized in the department of Neurology during 2018–2023 with at least two admissions; (3) having detailed medical history including height, weight, and laboratory test records; and (4) having no weight-loss medication or other specialized weight-loss treatments before the first visit to PUMCH. We excluded the patients who had taken MAO-B inhibitors, including selegiline and rasagiline before the first visit to PUMCH. We reviewed all medication histories and collected characteristics such as sex, age, height, and body weight. The outcome variables were changes in body weight and body mass index (BMI). Patients who took iMAO-Bi, including selegiline and rasagiline, were assigned to the iMAO-Bi group. The initial dose of selegiline was 5 mg qd, and could be increased up to 10 mg qd according to the treatment effect. The initial and maximum dose of rasagiline was 1 mg qd. The control group consisted of patients who were not administrated with iMAO-Bi.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to evaluate the changes in BMI and body weight among groups. We adjusted ANCOVA models with sex and follow-up time, as both factors might have potential influences on body weight and BMI. We calculated the least-squares means and two-sided 95% confidential intervals (CIs) from ANCOVA models. We also compared BMI and bodyweight differences between the iMAO-Bi and control groups with the two independent sample t-tests. We conducted a subgroup analysis to explore the potential BMI and bodyweight changes after short-term and long-term observations of iMAO-Bi treatment. As the median treatment duration of iMAO-Bi was six months, we defined patients treated with iMAO-Bi for less than six months as short-term therapy and those who received iMAO-Bi for equal to or more than six months as long-term therapy. The statistical software that was used for statistics in this study was IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, version 27.0.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 37 eligible participants were included in this cohort, 23 of whom were treated with iMAO-Bi. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The iMAO-Bi group had an average age of 65.87 years, and 71.4% were male patients. In the control group, the average age was 61.36 years, 52.2% of whom were male. The baseline BMI was 24.73 kg/m2 in the iMAO-Bi group and 22.79 kg/m2 in the control group (P = 0.090); the average body weight was 67.78 kg in the iMAO-Bi group and 64.46 kg in the control group (P = 0.395). Except for iMAO-Bi, other medication histories appeared similar between the two groups. The median administration duration of the iMAO-Bi group was six months; 47.8% (11/23) had a short-term iMAO-Bi therapy.

Weight loss outcomes in the iMAO-Bi and control groups

Table 2 shows BMI and body weight for patients in the iMAO-Bi and control groups at baseline and follow-up. According to the ANCOVA models, the least-squares mean change from baseline BMI was a 0.09 kg/m2 decrease. The transition from baseline body weight decreased by 0.15 kg in the iMAO-Bi group, as compared with a reduction in BMI of 0.03 kg/m2 and an increase in body weight of 0.07 kg in the control group. The least-squares mean difference in follow-up BMI between the iMAO-Bi group and control group was −0.07 kg/m2 (95% CI: −1.08 to 0.96; P = 0.897), and the least-squares mean difference in follow-up bodyweight was −0.22 kg (95% CI: −2.97 to 2.52; P = 0.868) (Table 2). The two independent sample t-test showed similar results. The mean BMI reduction in the iMAO-Bi group was 0.03 kg/m2 more than the control group (95% CI: −0.87 to 0.80; P = 0.936); mean bodyweight reduction in the iMAO-B group was 0.02 kg, while mean weight was slightly increased by 0.11 kg in the control group, yet having no significant difference between the two groups (−0.13 kg; 95% CI: −1.82 to 2.03; P = 0.911). In the short-term follow-up subgroup, the mean BMI and body weight were reduced by 0.17 kg/m2 (95% CI, −0.77 to 0.42) and 0.36 kg (95% CI: −1.93 to 1.20), respectively; in contrast, both BMI and bodyweight showed a slight increase in the long-term subgroup. Although the differences between the two subgroups were insignificant, the trends of reducing body weight and BMI in the short-term subgroup still could be recognized.

Discussion

The background of previous studies on the anti-obesity mechanism of MAO-B inhibitors and the clinical verification of our study were comprehensively illustrated in a schematic diagram (Fig. 1). In general, we observed a slight but insignificant trend of weight loss by iMAO-Bi among PD patients by multiple verifications. We reported for the first time the anti-obesity effects of iMAO-Bi in both short-term and long-term administrations. According to our small-scale cohort study, iMAO-Bi did not show a significant anti-obesity impact in patients with PD, which was consistent with the results of animal experiments [3]. However, it may be too early to draw a conclusion. Previous studies have reported that selegiline can significantly reduce astrocytic reactivity in the short term in AD model mice by markedly suppressing hypertrophy and astrogliosis in addition to astrocytic GABA, which may also be applied to weight loss mechanisms in humans [6,7,8]. Furthermore, selegiline has protective effects against inflammatory response, oxidative stress, and hepatic lipid metabolism by reducing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines [9]. Our study showed a possible trend of weight loss in a short-term iMAO-Bi treatment compared with the long-term treatment. Moonsun et al. also suggested that selegiline caused a transient reduction in body weight before the turning-on of the GABA-synthesizing enzyme diamine oxidase [3, 4]. Thus, more comprehensive large-scale studies and experiments should be performed to verify the clinical anti-obesity effectiveness of iMAO-Bi, either in a short-term or long-term treatment. On the other hand, rMAO-Bi is becoming a promising alternative anti-obesity drug by reversibly occupying the active site of MAO-B without inducing compensatory mechanisms [3, 4], which should be verified in further study.

This diagram summarizes previous research in the sections “Background” and “Mice model”. Our study, which verifies the potential anti-obesity effects on humans, is presented in the “Clinical verification” section. Key points for future research are highlighted in the lower section.

There are several limitations in our study. One concern about the findings was the limited sample size in our study. We only included patients with multiple admissions, as they had comprehensive clinical evaluations in medical history and laboratory results. Additionally, we only included patients with PD in our study, while patients with other neurological disorders administrated with iMAO-Bi should also be involved. This study may also be limited by potential confounders, which could not be fully corrected in a retrospective study. Despite these, our results shed light on how iMAO-Bi can affect human body weight and pave the way for larger scales of clinical research and the development of anti-obesity drugs.

Responses