Anti-obesity medication for weight loss in early nonresponders to behavioral treatment: a randomized controlled trial

Main

Current obesity management guidelines recommend a ≥6-month course of behavioral treatment (BT) that includes a reduced-calorie diet, increased physical activity and behavioral strategies to facilitate goal adherence as the first intervention for improving weight and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk1,2. On average, patients lose 5–8% of initial weight after 4–6 months of high-intensity BT (that is, ≥14 sessions in 6 months), with smaller mean losses in less intensive programs2. A loss of ≥5% of initial weight is a common criterion for clinically meaningful weight loss and is associated with improvements in CVD risk factors3. However, 35–50% of patients fail to lose this amount with high-intensity BT4,5.

Slow early weight loss in the first 1–2 months of BT is a strong predictor of limited total weight loss after 6–12 months of treatment5,6,7. Approximately one-third of participants lose <0.5% of body weight per week in the first month of intensive BT, and the majority of these early nonresponders (53–70%) do not achieve a loss of ≥5% initial weight after 6 months of treatment5,7. Some investigators have suggested that BT nonresponders be provided an additional therapy or a different intervention altogether as early as possible, rather than spending ≥6 months in a treatment that is unlikely to facilitate a clinically significant weight loss5,6,7. Early nonresponders to BT can become discouraged about reaching their desired weight loss goals and are more likely to drop out of treatment6,8.

Several studies have examined the efficacy of stepped-care approaches for obesity treatment in which BT is intensified for patients who do not meet early weight loss milestones. The baseline treatment offered in these programs has typically been of low intensity, consisting of self-help, internet-based or monthly BT visits, and treatment has primarily been intensified by increasing provider contact rather than by offering an adjunctive intervention9,10,11. To our knowledge, no studies have investigated whether a rapid step-up approach improves weight loss in early nonresponders who are already receiving 6 months of intensive BT.

Expert panels have recommended the addition of anti-obesity medications (AOMs) approved for chronic weight management for individuals with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg m−2 (or BMI ≥ 27 kg m−2 with comorbidity) who are unable to lose weight or sustain weight loss with BT alone1,2. For example, the 2014 updated guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for the management of overweight and obesity stated that the addition of medication should be considered for adults ‘only after dietary, exercise, and behavioral approaches have been started and evaluated, and a target weight loss has not been reached or a plateau has been reached’2. Multiple studies have shown that the addition of AOM to either high- or low-intensity BT significantly increases mean weight loss, as compared to BT with placebo12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Studies evaluating the efficacy of AOMs have either initiated medication simultaneously with BT16,17,18,19,20, or have only randomized patients to AOM or placebo (for maintenance) if they first achieved a certain weight loss criterion (for example, ≥5%) with BT12,13,14,15. Remarkably, the recommendation to offer AOM to individuals who are unable to successfully lose weight with BT alone has never been tested in a randomized trial.

Phentermine hydrochloride is a sympathomimetic amine thought to reduce appetite and food intake by increasing norepinephrine and possibly catecholamine levels in the hypothalamus20,21,22. Phentermine was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1959 and by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 1996 for ‘short-term’ use, commonly interpreted as 12 or fewer weeks. In 2012, the FDA also approved the combination of phentermine (7.5–15.0 mg d−1) plus topiramate for long-term weight management (for example, ≥12 months20). (The EMA, however, declined approval for this combination medication.) Phentermine (monotherapy) is the most widely used AOM in the US and is frequently prescribed in clinical practice for periods longer than 12 weeks21,22. Patients without diabetes achieve average placebo-subtracted weight losses of 3.6–7.4 kg after 12–28 weeks of treatment with phentermine (15.0–30.0 mg d−1 (refs. 19,20,21,22,23)).

‘Assessing BEhavioral Traits and Tracking Early Response to Find Individualized Treatments’ (A BETTER FIT) was a single-center, double-blinded, parallel-group design randomized controlled trial. This proof-of-principle study tested whether augmenting intensive BT with AOM (phentermine = 15.0 mg) would improve 24-week weight loss, as compared to BT with placebo, in participants identified as early nonresponders to behavioral weight control. All participants completed an initial 4-week BT run-in intervention delivered individually in 20–30-min weekly sessions (phase 1). Participants who lost <2.0% of initial weight during the BT run-in were considered early nonresponders and were randomly assigned to an additional 24 weeks of (1) BT plus placebo (BT + P) or (2) BT plus AOM (BT + AOM; phentermine = 15.0 mg d−1; phase 2). Intensive BT was provided to both groups so that we could compare this early step-up approach to the recommended standard of ≥6 months of BT that participants would have received if early weight loss had not been evaluated. Early responders who lost ≥2.0% during the 4-week run-in continued to receive BT alone during phase 2 and were not considered part of the randomized trial.

Results

Patient disposition

Phase 1: 4-week BT run-in

Between July 30, 2019, and November 15, 2021, 942 individuals were prescreened for eligibility by phone, 203 of whom underwent in-person screening. The 147 participants who passed the screening and enrolled in the 4-week BT run-in were predominantly female (87.1%, n = 128); 80 (54.5%) self-identified as white, 57 (38.8%) as Black and 5 (3.4%) as Asian; 7 (4.8%) identified as Hispanic. Participants had a mean baseline age of 48.5 years (s.d. = 12.4), weight of 104.6 kg (s.d. = 19.8) and BMI of 37.7 kg m−2 (s.d. = 6.4; Extended Data Table 1).

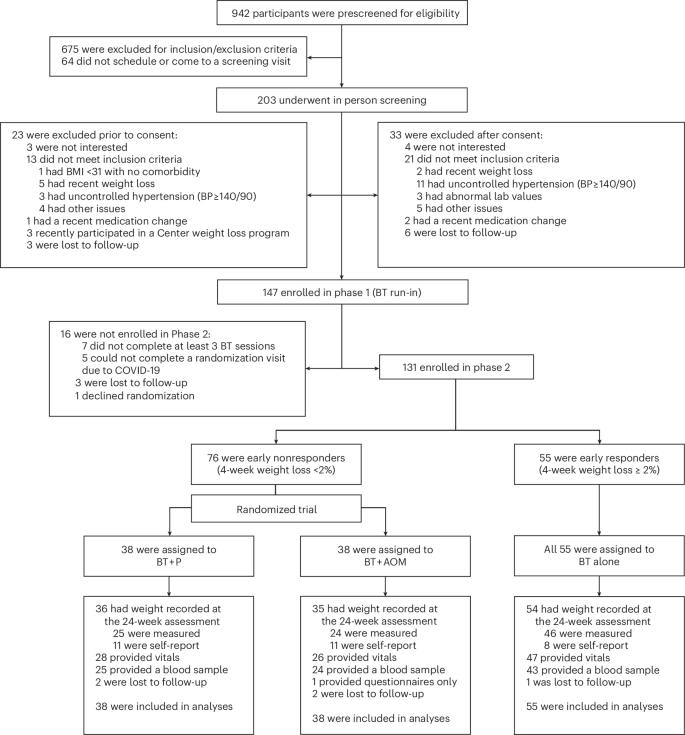

Figure 1 shows the progression of participants through the study. Sixteen participants did not enroll in phase 2, leaving 131 who did. Of those, 76 (58.0%) were categorized as early nonresponders, losing <2% of initial weight in phase 1, and 55 (42.0%) as early responders (losing ≥2%). On average, early nonresponders lost 0.6% (s.d. = 1.1) of initial weight in phase 1, and early responders lost 3.1% (s.d. = 1.0, P < 0.001). Extended Data Fig. 1 shows individual participants’ phase 1 weight losses.

Flow chart describing participant recruitment and progression through the study. CONSORT, consolidated standards of reporting trials.

Phase 2: 24-week randomized trial

Table 1 shows the 76 early nonresponders’ characteristics at the time of randomization (week 0) to BT + P (n = 38) or BT + AOM (n = 38). Those assigned to BT + P had lost 0.9% during phase 1, compared with a 0.3% loss for those assigned to BT + AOM.

Overall, 93.4% (71/76) of early nonresponders provided a weight measurement at week 24 (Fig. 1). Weight was measured remotely using digital scales provided by the study for 19 early nonresponders due to a 3-month suspension of in-person activities in response to the novel coronavirus, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Five of these individuals returned later to provide in-person measurements of weight and vital signs. Vitals were missing for the 14 nonresponders (18.4%) who completed only remote measures, and laboratory outcomes were missing for all 19 (25.0%). These data were considered missing completely at random. An additional three early nonresponders elected to complete the week-24 assessment remotely after our site reopened. Thus, a total of eight (10.5%) nonresponders had missing vitals and laboratory outcomes that were attributable to noncompletion of some or all portions of the week-24 assessment for reasons unrelated to the COVID-19 suspension. Most participants (16/22; 72.3%) who were missing week-24 vitals had provided those measurements during at least one postrandomization BT visit.

Primary outcome

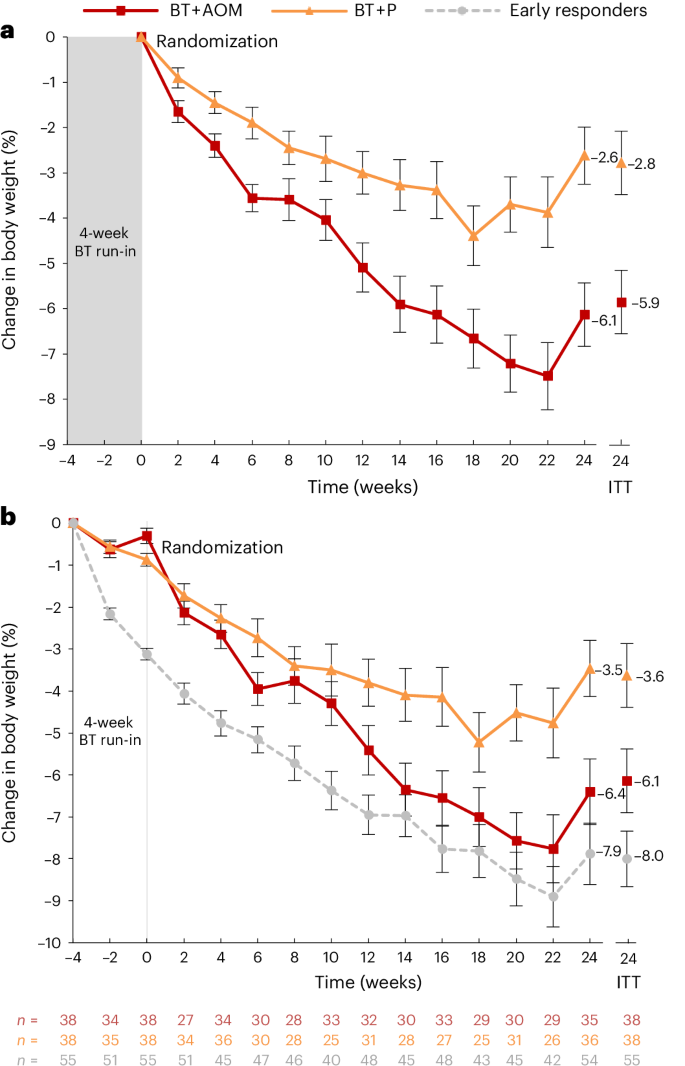

From randomization (week 0) to week 24, early nonresponders assigned to BT + AOM had a significantly greater mean (±s.e.) percent reduction in randomization body weight of 5.9 ± 0.7% (95% confidence interval (CI) = 4.4–7.2%) compared to the 2.8 ± 0.7% (95% CI = 1.4–4.1%) reduction in those assigned to BT + P (estimated mean difference = 3.1 ± 1.0%, 95% CI = 1.1–5.1%; Table 2, Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2). We re-ran the primary outcome models controlling for phase 1 weight loss and results were similar to those presented in the text (Supplementary Table 1).

a, Mean (±s.e.) percent changes in body weight as measured from randomization to week 24 in the 76 early nonresponders randomized to BT + AOM (phentermine = 15.0 mg d−1) or BT plus placebo. b, Mean (±s.e.) percent changes in body weight as measured from baseline of the 4-week BT run-in in the 76 early nonresponders randomized to BT + AOM or BT + P, as well as changes in the 55 early responders who were not randomized. Weekly values include participants who both completed the BT session and provided a weight measurement. The body weights of all enrolled individuals were captured at the assessments at weeks −4, 0 and 24. The uptick in measured weight at week 24 is likely attributable in whole or in part to the inclusion of individuals whose weights were not consistently captured before week 24. Week 24 intention-to-treat values were obtained from linear mixed model analyses. Modeled estimates for all time points can be found in Extended Data Fig. 2.

Secondary outcomes

From week 0 to week 24, 53.9% of BT + AOM participants lost ≥5% of body weight compared to 25.3% of participants assigned to BT + P (χ2(1) = 6.32, P = 0.012). The groups did not differ significantly in the percentage that achieved a postrandomization loss ≥10% at week 24 (19.2% and 5.5%, respectively; χ2(1) = 3.11, P = 0.078). Table 2 shows additional weight change outcomes and waterfall plots are included in Extended Data Fig. 3.

BT + AOM participants had a mean increase in systolic blood pressure (BP) of 6.6 ± 1.9 mm Hg from randomization to week 24, which was significantly different from the 0.7 ± 1.8 mm Hg reduction in the BT + P group (Table 3). Group differences in diastolic BP and heart rate did not reach statistical significance but followed a similar pattern. The groups did not differ significantly in change from randomization in any other secondary endpoint (Table 3). Collapsing across the two groups, there were significant improvements from randomization in triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.

Safety

Overall, 23 (60.5%) BT + AOM participants and 27 (71.1%) BT + P participants reported at least one adverse event (AE), with no serious AEs during the trial. Events that appeared more frequently in BT + AOM than BT + P were headache (18.4% versus 5.3%), dry mouth (10.5% versus 0%) and difficulty in sleeping (7.9% versus 0%). A full list of AEs affecting >5% of participants in either group can be found in Extended Data Table 2. Treatment was not terminated nor was phentermine/placebo downtitrated in any participant at the recommendation of the study physician, and no AEs likely to be related to study participation or medication usage resulted in treatment discontinuation. Five BT + P participants and three BT + AOM participants were off-drug for other reasons at the time of their last study contact (Extended Data Table 2); all but one of these provided at least partial outcome data at week 24.

Exploratory outcomes

There were no significant differences between the randomized groups in any exploratory endpoint (Table 3). Collapsing across the two groups, there were significant improvements from randomization in weight-related quality of life (QOL), cognitive restraint, hunger and physical activity level.

Exploratory analyses revealed that early responders who received BT alone lost 5.1 ± 0.6% of their body weight from week 0 to week 24 of phase 2 (the period of the randomized trial), which was significantly more than early nonresponders assigned to BT + P (2.8%) but did not differ significantly from the weight loss of nonresponders assigned to BT + AOM (5.9%; Extended Data Table 3). A postrandomization loss at week 24 of ≥5% was achieved by 46.5% of early responders and 14.7% lost an additional 10% during that time (Extended Data Fig. 4). Total weight loss as calculated from baseline of the BT run-in (week −4) was 4.4 ± 1.0 percentage points larger in early responders as compared to BT + P (8.0% versus 3.6%); the difference of 1.9 ± 1.0 percentage points compared to BT + AOM did not reach statistical significance (8.0% versus 6.1%; Fig. 2b). Comparisons between the three groups in secondary outcomes can be found in Extended Data Table 4.

Post hoc analyses

Because we had expected only 33–40% of the sample to be classified as early nonresponders, we conducted a post hoc analysis comparing BT + AOM with BT + P in the subset of 50 participants (38.2% of the phase 2 sample) who lost <1.25% of baseline weight in phase 1. Postrandomization weight loss was 3.6 ± 1.2 percentage points greater (95% CI = 1.2–6.1%) in BT + AOM (n = 30) than BT + P (n = 20) in this subsample (P = 0.004; Extended Data Table 5).

Discussion

The study’s principal finding was that the addition of the AOM, phentermine of 15.0 mg d−1, more than doubled the mean weight loss at 24 weeks postrandomization in individuals receiving intensive BT who had suboptimal weight loss in the first month of that treatment. Overall, the postrandomization weight loss of early BT nonresponders treated with phentermine was 3.1 percentage points higher than that of placebo-treated nonresponders. Only 25.3% of early nonresponders achieved a weight loss of ≥5% from randomization to week 24 with the current standard of care of 6 months of intensive BT (with placebo), whereas over half (53.9%) achieved this target when AOM was added. The present results strongly support clinical guidelines that recommend the addition of AOMs for patients who do not achieve clinically meaningful weight loss with BT alone1,2. They also suggest that AOMs can be introduced early in treatment once lack of response to behavioral intervention has been observed rather than waiting ≥6 months to modify therapy.

The present study also established that a stepped-care approach can benefit patients who are already receiving intensive BT. The results demonstrated that individuals at risk of suboptimal response, as defined by their loss of <2% of initial weight in the first 4 weeks, can achieve a weight loss similar to that of early (strong) BT responders if provided with adjunctive AOM at that time. Although not significantly different, the postrandomization weight loss of early nonresponders treated with AOM was slightly higher (0.8 percentage points) than that of early responders and the two groups did not differ significantly in total weight loss as measured from the start of the 4-week BT run-in (6.1% and 8.0%, respectively). On the other hand, placebo-treated early nonresponders lost less weight than early responders throughout both phases of the trial. A great majority of early BT nonresponders (75%) did not achieve a clinically meaningful weight loss of ≥5% from randomization with 24 more weeks of intensive BT (combined with placebo). These outcomes question whether it is clinically appropriate to continue to recommend ≥6 months of BT as the standard of care for patients with obesity without also stipulating that early weight loss should be evaluated and alternative treatments considered for those with suboptimal early weight reduction.

The ability to establish recommendations for clinical practice will be further enhanced by optimizing the timing and weight loss thresholds used to identify individuals in need of additional intervention. The 2% threshold applied at week 4 in the present study classified 58% of participants as early nonresponders, whereas we expected that 33–40% would be so characterized5,7. This may have been because the format of the treatment (brief, individual sessions) differed from that of previous studies of early weight loss thresholds5. It is also possible that some randomized individuals were not at high risk of suboptimal weight loss, given that 25% of placebo-treated participants did go on to lose ≥5% of their randomization weight. A lower 4-week weight loss threshold may have allowed us to more accurately classify such individuals. However, we did not find evidence that differences between the randomized groups were driven by the inclusion of participants with moderate early weight loss. Post hoc analyses showed that the addition of AOM was also beneficial for the 38% of participants who lost <1.25% during the BT run-in. Assessing weight loss progress at more than one timepoint may better differentiate slow starters who will later achieve a clinically meaningful weight loss from those who are truly at risk. Multistage assessment also could provide the opportunity to modify later treatment for the minority of early responders who do not ultimately achieve a ≥5% reduction in body weight.

We also could not determine whether the structure and features of the initial BT run-in influenced which patients lost weight early in treatment. Consistent with other BT protocols modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program24 and Look AHEAD25, the first month of the present program focused on initiating self-monitoring and making self-selected dietary changes designed to produce a 500–750 kcal d−1 deficit. We do not know whether the population of early nonresponders selected would have differed if an alternative dietary strategy had been recommended (for example, a less energy-restricted diet) or if physical activity or other behavioral strategies had been more prominently emphasized early in treatment. Thus, the generalizability of the present findings may be limited to nonresponders in BT programs with similar early features.

Our study demonstrated that the AOM phentermine was an effective method of improving 24-week weight loss in early BT nonresponders. Further study, however, is needed to determine whether these effects are maintained in the long-term and to establish the benefit of other AOMs in this population. In particular, recommendations to first undergo a course of BT may need to be modified in the context of newer AOMs (for example, semaglutide and tirzepatide) that produce mean weight losses that are substantially greater than those of even strong responders to BT26,27,28. Additional methods for rapidly stepping up care for nonresponders to intensive BT also should be evaluated, including behavioral methods such as intensifying support, adding psychological intervention strategies, modifying dietary targets, or providing meal replacements. These strategies remain important even in the context of newer AOMs given that not all patients with obesity are willing, eligible, or able to access pharmacotherapy or other medical interventions (for example, metabolic-bariatric surgery28). Identifying differences in treatment engagement and response other than early weight loss that predict treatment outcomes might ultimately be used to individualize the selection of an adjunctive intervention from a broader list of strategies.

Consistent with the known safety profile of phentermine19,20,21,22,23, headache, dry mouth and difficulty in sleeping were reported by a minority of AOM-treated participants (8–18%) and occurred more commonly than with placebo. The medication was generally well tolerated. However, phentermine-treated participants experienced larger-than-expected mean increases from randomization in systolic and diastolic BP of 6.6 and 4.9 mm Hg, respectively. Placebo-treated participants experienced small reductions in systolic BP that differed significantly from the increases observed in the AOM group. Diastolic BP increased from randomization in both treatment groups (as well as in early responders), whereas we had expected a small decrease with weight loss3. This overall increase does not explain why the effect was (nonsignificantly) larger with phentermine. Although uncontrolled hypertension is a contraindication for phentermine use, most studies have reported a decrease in BP during treatment19,20,21,22,23. In one of the largest controlled trials, participants randomized to 28 weeks of phentermine 15.0 mg d−1 had reductions of 3.5 mm Hg in systolic BP and 0.9 mm Hg in diastolic BP that did not differ from placebo-treated participants20. Heart rate also appeared to increase with phentermine in the present study, although the comparison to placebo did not reach statistical significance. This finding is more consistent with previous studies, which have reported mean increases of 1–2 beats per min20,22. The elevated BP readings in our study could be related to our small sample size or to unexpected effects resulting from the provision of a 4-week behavioral run-in before participants received phentermine. Nonetheless, the BP and heart rate values both represent potential safety concerns for which we recommend regular monitoring in patients treated with phentermine.

The primary limitation of this study was the relatively small sample of randomized participants, which was not adequately powered to detect group differences in outcomes other than percent reduction in body weight. Comparisons between the randomized groups in changes in secondary outcomes measuring CVD risk, QOL and depression, which tend to improve more in patients with larger weight losses3, did not reach statistical significance. Collapsing across groups, participants experienced significant improvements from randomization to week 24 in HDL cholesterol, triglycerides and QOL. Exploratory outcomes including cognitive restraint, disinhibition, hunger and physical activity also improved across the groups with no significant group-by-time effects. It will be important to conduct a longer-term follow-up study that is fully powered to evaluate between-group differences. For example, the numerically greater increase in physical activity after randomization in the AOM group as compared to placebo did not reach statistical significance in this sample. However, this preliminary signal is worthy of follow-up in a larger study that could also evaluate whether the increase in physical activity contributed to additional weight loss in the AOM group or alternatively was a consequence of the greater weight loss achieved with the addition of phentermine.

The present study also could not determine whether the provision of ongoing BT to the early nonresponders was clinically useful after the AOM was initiated. Although studies suggest that the effects of BT and some AOMs are additive in the general population16,17, weight loss with the combination of BT and AOM has not been compared to therapy with AOM alone in an early nonresponder population, in which the benefit of ongoing BT is expected to be small. Given that BT is a resource-intensive treatment, a follow-up study that includes treatment arms that provide early BT nonresponders with AOM/placebo with no or minimal ongoing BT would help to identify the most cost-effective standard of care for these patients.

Our study’s strengths included the use of an innovative 4-week run-in program to identify BT nonresponders, followed by randomization to treatment. The trial also had high retention that resulted, in part, from efforts to mitigate the untoward effects of COVID-19 on both treatment delivery and the completion of in-person outcome measurements. We minimized the impact on the study’s primary outcome by using a uniform body-weight scale and self-weighing procedure. Self-reported weights were evenly distributed between randomized groups and our analyses suggested that the impact of remote measurement on weight loss outcomes was likely to be minimal. However, the suspension of in-person activities resulted in an additional 18–25% of participants not providing vitals and laboratory data, which may have further limited our ability to detect between-group differences in those outcomes.

In conclusion, the present study found that for individuals who had suboptimal weight loss with four initial weeks of BT, ‘stepping up’ treatment by adding an AOM (phentermine) to continued BT significantly increased 24-week weight loss as compared to 24 more weeks of intensive BT alone (plus placebo), the current standard of care for weight management. Safety signals suggested that BP and heart rate should be monitored regularly in phentermine-treated participants.

Methods

Study design

‘A BETTER FIT’ (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT03779048) was a single-center, double-blinded, parallel-group design randomized controlled trial, conducted at the University of Pennsylvania, whose institutional review board approved the study protocol (available at https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.pex-2526/v1). The trial was supervised by an independent data monitoring and safety committee. This proof-of-principle study had two phases. Phase 1 was a 4-week, nonrandomized BT run-in used to identify early nonresponders to BT. Phase 2 was the randomized trial in which those early nonresponders were then assigned to 24 more weeks of BT combined with either placebo or the AOM phentermine 15.0 mg d−1.

Participants

Individuals were eligible for phase 1 if they were aged 18–70 years and had a BMI ≥ 31 kg m−2 (or ≥28 kg m−2 with an obesity-related comorbidity). These BMI criteria were selected so that participants would still have a BMI appropriate for initiating AOM if they lost up to 2.0% of their weight during the BT run-in. Exclusion criteria included type 1 or type 2 diabetes or fasting blood glucose >126 mg dl−1 (upon second assessment); hyperthyroidism; other uncontrolled thyroid disease; narrow-angle glaucoma; use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; renal, hepatic or recent CVD; BP ≥140/90 mm Hg; medications that substantially affect body weight (for example, corticosteroids); substance abuse; current severe major depression, current suicidal ideation or history of suicide attempts within 5 years; bariatric surgery; use of weight loss medications or products; weight loss ≥5% in the past 6 months and pregnancy/lactation. Other chronic medications were permitted, provided they had been dose-stable for ≥3 months.

Procedures

Participants were recruited between July 2019 and November 2021 via print and social media advertisements. Applicants completed an initial phone screening, and those who appeared eligible then completed a screening visit with a psychologist (J.S.T.), who obtained written informed consent and assessed applicants’ behavioral and psychological eligibility. Individuals who passed this screening next met with a nurse practitioner who completed a medical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, fasting blood draw and urine pregnancy test (for females of child-bearing age) to determine final eligibility.

Phase I: BT run-in

Phase 1 (week −4 to week 0) was a 4-week, nonrandomized intervention used to identify early nonresponders to BT. Participants attended four weekly, 20–30 min individual weight loss sessions led by a psychologist, psychology postdoctoral fellows or upper-level predoctoral trainees. All interventionists had previous experience delivering BT and were trained and supervised by J.S.T. and T.A.W. The treatment protocol was modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program and Look AHEAD, adapted for brief individual session delivery29. During phase 1, participants were instructed to initiate self-monitoring and to consume a self-selected diet of 1200–1500 kcal d−1 for those who weighed <113 kg or 1500–1800 kcal d−1 for those who weighed ≥113 kg.

Randomization

To be eligible for phase 2, participants had to attend at least three of four BT run-in sessions (including makeup visits) and complete a randomization assessment at week 0. At that assessment, early nonresponders—who lost <2.0% of baseline weight—were randomly assigned 1:1 to the AOM phentermine (15 mg d−1) or placebo in permuted blocks of 2–4 participants via random number tables. Randomization was performed by Penn’s Investigational Drug Services, which provided the study medications in blinded capsules. All participants, including early responders who were not eligible for randomization, were offered BT for 24 additional weeks.

The selection of a 2.0% weight loss to define early treatment response was based on a study that evaluated the accuracy of different early weight loss thresholds at 1 and 2 months in predicting 1-year weight loss in participants in the Look AHEAD study who received intensive BT5. These findings indicated that a 2.0% cutoff yielded the highest specificity (78%), or lowest false positive rate (22%), in predicting achievement of a ≥5% loss at 1 year (that is, only 22% of individuals who had a weight loss <2.0% at 1 month had a ≥5% loss at 1 year), which matched our goal of selecting participants at highest risk of not achieving a clinically meaningful weight loss with BT alone5. A threshold of 3.0% at month 2 had marginally higher specificity, but the potential costs—both in terms of resources for extending the initial BT treatment and the risk that more participants who were dissatisfied with their weight loss progress might drop out if randomization was delayed—were thought to outweigh the marginal improvement in our ability to identify high-risk patients.

Phase 2: randomized trial

In phase 2, all participants continued to attend individual, 20–30 min BT sessions weekly for 12 weeks, then every other week until week 24 (a total of 18 sessions). They were instructed to continue following their calorie goal and to self-monitor their food intake, physical activity and weight. Participants were instructed to engage in low-to-moderate intensity physical activity (for example, walking), gradually building to a goal of ≥180 min per week. They were provided a curriculum on behavioral weight control that included stimulus control, goal-setting, problem-solving, cognitive restructuring and relapse prevention29. By matching our BT treatment protocol and program duration to the recommendations of current guidelines for the treatment of obesity1,2, we sought to be able to compare the standard of care that these participants would otherwise have received (with placebo) to a new, rapid step-up approach.

Early nonresponders were assigned to take study medication (phentermine or placebo), beginning at randomization and received a 30-day supply on six occasions. Phentermine was provided as 8.0 mg d−1 for the first 2 weeks to facilitate its acceptance. The dose was then increased at week 2–15 mg d−1 (or further placebo). Phentermine (or placebo) could be downtitrated to 8.0 mg d−1 or terminated in individuals who reported that they could not tolerate the medication. The FDA did not require an Investigational New Drug application to use phentermine for 24 weeks in the present study.

No additional treatment was provided after week 24. All participants received counseling in their final sessions that included resources for ongoing weight loss, including an overview of phentermine and other AOMs. Participants were offered a letter that summarized the study treatment they had received, which could be used to discuss treatment options with other health professionals.

Outcomes

Outcome assessments were completed at baseline (week −4), randomization (week 0) and week 24. Participants received $75 for completing the final assessment. Participants’ demographic information, including their age, sex assigned at birth, race and ethnicity was collected via a self-report questionnaire at baseline. For all categorical classifiers (for example, race), a list of terms was provided by the researchers, but participants could select to write in a different response. Participants could select one or more categories or could decline to respond.

The randomized trial’s primary outcome was the percentage change in initial body weight as measured from randomization (week 0) to week 24. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg by trained staff using a digital scale (Tanita, BWB800) with participants dressed in light clothing, without shoes. Body weight and vital signs were also measured at all in-person BT visits using this method. Two measurements were taken on all occasions.

Secondary endpoints included the portion of nonresponders who achieved a postrandomization loss of ≥5% and ≥10% of body weight, as measured from randomization to week 24, as well as 24-week changes in resting BP, pulse, fasting glucose, triglycerides, lipids, QOL and mood. The Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite30 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (ref. 31) were used to assess the latter two outcomes. Exploratory endpoints included changes in cognitive restraint, disinhibition and hunger as measured by the Eating Inventory32 and in physical activity minutes per week, assessed by the Paffenbarger Physical Activity Survey33. An additional exploratory aim was to compare the randomized groups to the nonrandomized early responders in percent weight loss from randomization. Monitoring for AEs was conducted through systematic queries at the assessments. Participants were also instructed to report any changes in health to study personnel at any clinic or BT visit. Medical personnel followed up on reported AEs to assess the severity and possible relatedness to the study.

Impact of COVID-19

From March 16 to June 8, 2020, in-person activities were suspended for nonessential clinical trials in response to the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. At that time, 47 participants were actively enrolled in the trial. All BT sessions were offered remotely via secure videoconferencing (or phone) thereafter, consistent with the study’s original protocol for makeup visits and subsequently adopted as the primary delivery method. The five participants who were enrolled in phase 1 on March 16 could not complete a randomization visit and therefore were ineligible for phase 2. Participants completing treatment were shipped digital scales (EatSmart, ESBS-01) and instructed to measure body weight for their remote 24-week assessment using a uniform procedure.

There were no significant differences in the postrandomization weight losses of patients with self-report versus measured weights (Cohen’s d = 0.10). Mean weight was 0.21 kg (s.d. = 0.24, median = 0.15 kg, interquartile range = −0.37 to 0.002) lower with home-measured weights in a subset of participants who were asked to self-weigh using the assessment procedure before their in-person assessment. We conducted a sensitivity analysis using pattern mixture models34 in which measurement source (measured, self-report or missing) was included in the mixed model. Results were similar to those reported in the text (Supplementary Table 2).

A priori power calculation

We predicted that the BT + AOM group would lose 4.5% more of body weight than the BT + P group from randomization to week 24, with expected s.d. of 5.5% in both groups (effect size, d = 0.82 (ref. 20)). Assuming a 20% attrition rate, a randomized sample of 50 nonresponders (25 per group) was expected to provide 81.5% power to detect between-group differences at week 24 in the primary outcome (two-tailed α level = 0.05). We anticipated that at least 33% of phase 1 participants would be categorized as early nonresponders5,6,7. Therefore we planned to enroll 150 participants in phase 1 to achieve a randomized sample of ≥50 early nonresponders.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted in SPSS Statistics v.28.0.1.1. Mean percentage reductions in initial weight in the intention-to-treat population were compared using mixed-effects models, which estimate missing data via residual maximum likelihood. Treatment group was entered as a between-subjects factor and time (week) was a within-subjects factor. The model’s shape (quadratic) and variance-covariance structure (unstructured) were selected based on the −2 log likelihood and Akaike’s information criterion. The group x time interaction was used to test differences in weight change from randomization to week 24 (primary endpoint) at a two-tailed α level of 0.05 and least squared means were compared to interpret significant effects. Similar mixed-effects models were fit to compare changes in BP and heart rate. Sensitivity analyses including baseline demographic covariates (age, race, sex and starting weight) and completer analyses yielded similar results (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

In mixed-effects analyses with only two time points, individuals with missing data do not contribute to slope estimation, resulting in a completer analysis. Thus for laboratory and questionnaire data, which were only collected at the assessments, we first applied multiple imputations using chained equations with predictive mean matching to estimate missing values. Twenty iterations were determined to be sufficient based on the fraction of missing data35. The above demographic characteristics, treatment condition, percent weight loss from baseline of the run-in (week −4) to randomization and postrandomization weight loss were included as predictors in the imputation model and an outcome’s values at baseline, randomization and week 24 were both predictors and outcomes of the imputation. Mixed-effects models were then applied, and results were pooled using Rubin’s rules36. For secondary and exploratory outcomes for which there was no significant group x time interaction (that is, indicating that the randomized groups did not differ significantly in change over time), the main effect of time, collapsing across groups, was evaluated.

Multiply imputed end-of-treatment weights also were used to calculate whether participants with missing data achieved a postrandomization loss ≥5% and ≥10% of initial weight at week 24. Treatment groups were compared on these categorical outcomes using chi-square tests, and results were pooled using R (v.4.2.2) package miceadds37. Because the study was not powered to detect differences in secondary endpoints, no α correction was used and these results should be interpreted with caution.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses