Antiageing strategy for neurodegenerative diseases: from mechanisms to clinical advances

Introduction

According to the 2022 World Health Organization (WHO) report, the speed of population ageing in countries around the world is far faster than that in the past, and the number and proportion of elderly individuals are on the rise. From 2020 to 2050, the global population aged 60 years and over is projected to increase from 1 billion to 2.1 billion, while the number of people aged 80 and over is expected to triple to 426 million. Due to the prosperous development of biomedicine, human life and life expectancy continue to rise worldwide, which is not consistent with the healthspan.1 The gap in lifespan and healthspan means that large numbers of older people are living with age-related diseases for long periods, imposing a substantial economic and caregiving burden on families and society. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are proposed, including years lived with disability (YLDs) and years of life lost (YLLs), to quantify the burden caused by diseases. In 2021, for individuals aged 60–79 years, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other forms of dementia ranked second among the top three leading causes of DALYs, whereas Parkinson’s disease (PD) ranked third for those aged 80 years and older.2 Neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, PD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), Huntington’s disease (HD) and others, are major diseases that cause dementia, disability, loss of independence and even death in elderly individuals. The incidence of neurodegenerative diseases is substantially increasing in the elderly population; dementia currently affects more than 55.2 million individuals worldwide, and this number is projected to reach 78 million by 2030 from the World Alzheimer Report 2021.3 AD is the most prevalent type of dementia, accounting for 60–80% of cases.4 PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease, with a rapid increase in incidence after the age of 50 years. According to the 2019 WHO estimates, 850,000 people suffer from PD worldwide. In general, in the context of accelerated global ageing, the global burden of other neurodegenerative diseases, such as ALS, HD and FTLD, is increasing. Society bears a heavy burden of increasing neurodegenerative disease costs.5 For example, the global costs of dementia are expected to increase nearly tenfold to $9.12 trillion from 2015 to 2050,6 and a similar situation is predicted for other neurodegenerative diseases.7,8

The ageing process is accompanied by the accumulation of genetic mutations and epigenetic changes, which gradually disrupt functional homoeostasis at the molecular and cellular levels, leading to loss of proteostasis and abnormal mitochondrial function. In the context of neurodegenerative diseases, proteostasis loss substentially contributes to the abnormal accumulation of various pathological proteins, including amyloid-beta (Aβ), hyperphosphorylated tau, α-synuclein (α-syn), TAR DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43), huntingtin (HTT). These aberrant proteins act as activators for glial cells, triggering neuroinflammation and other pathological events. Subsequent inflammation exerts detrimental effects on neurons, resulting in neuronal injury, disruption of neural circuitry, and eventual manifestation of diverse neurodegenerative disorders.

Regrettably, current therapeutics are severely limited, and no interventions are available to stop or even reverse the course of these diseases. The clinical interventions for PD, FTLD and HD have concentrated on symptomatic treatment and nonpharmacological approaches (e.g., lifestyle modifications, peer and caregiver support), and no efficacious drug has been demonstrated to have disease-modifying effects on patients.9,10,11 Although electroencephalogram-based brain‒computer interface (BCI) technology can help ALS patients communicate with the outside world via real-time speech synthesis and robotic arms,12,13 disease progression cannot be affected. For HD, clinical trials of drugs targeting proximal molecules, namely, HTT DNA, RNA and protein, are underway and may be available to modify the disease course in the future.14 Surprisingly, recent clinical trials of Aβ-targeted immunotherapies have shown their efficacy in slowing cognitive decline.15 Nevertheless, the overall cognitive benefits of these treatments are limited once the dementia stage has taken hold.16,17,18 These realities highlight the urgent need to explore more effective therapeutic strategies for ageing-related neurodegenerative diseases.

Impact of ageing on neurodegenerative diseases

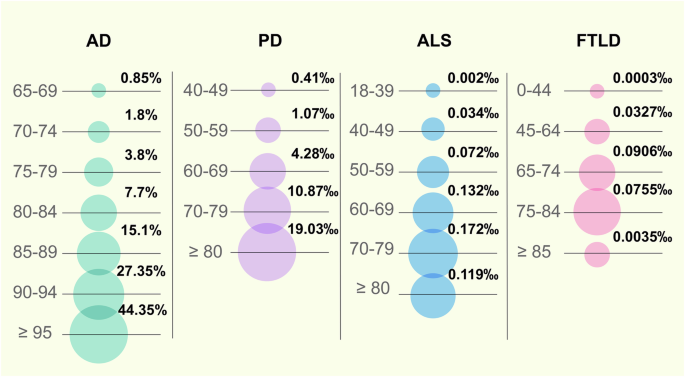

Ageing encompasses suborganismal biological processes leading to declines in organismal survival and function over time,19 which is the basis of many chronic diseases. The incidence of AD increases exponentially after the age of 65.4 Epidemiological studies have documented a significant increase in the percentage of individuals with AD with age, especially women, which were reported as early as 2000.20 In 2022 in the United States, the percentage of individuals with AD ranged from 5% among individuals aged 65–74 years, 13.1% among individuals aged 75–84 years, and 33.2% among individuals aged 85 years and above.21 The incidence of PD also increases with increasing age, and whether this association is linear or exponential is unclear.22 Based on the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases, an analysis was conducted to determine the global prevalence of PD between 1985 and 2010 across different age groups. Comparing the prevalence rate of PD at 41 per 100,000 among individuals aged 40–49 years, it was found that those aged 80 years and older exhibited a significantly higher prevalence rate of PD at 1903 per 100,000.23 As the resource from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, the ALS prevalence rate was the lowest among individuals aged 18–39, with only 0.2 cases per 100,000 people. In contrast, the prevalence rate was highest in the 70–79 year age group, reaching 17.2 cases per 100,000 people.24 Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that usually begins in the late 50 years to early 60 years. The prevalence of MSA increases with age, with a peak occurrence in individuals aged 50–70 years. Recent statistics indicate that MSA affects approximately 4.6 per 100,000 people aged 50–59 years, increasing to 7.8 per 100,000 in those aged 70–79 years.25 Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) typically manifests between the ages of 50 and 70 years. Its prevalence increases with age, with the most common onset occurring in the middle 60 years. Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is another form of tauopathy commonly observed in individuals around their mid-60 years. Its prevalence notably increases with advancing age, often manifesting more prominently in those aged 70 years and older. This condition is characterized by the progressive accumulation of the tau protein in the brain, which becomes more prevalent with advancing age.26 FTLD is commonly identified in individuals between 45 and 65 years of age, yet its risk and occurrence increase with ageing. Research indicates an increased occurrence among older individuals, notably individuals aged 60 years and older.27 A retrospective analysis across Europe revealed that the average incidence of FTLD peaks at the age of 65–74 years, with 9.06 cases per 100000 person-years.28 Furthermore, according to an Italian epidemiological report, the prevalence rate of HD ranges from 4.35 per 100,000 individuals aged 40–44 years to 49.67 per 100,000 individuals aged 65–69 years.29

Given that ageing is a common risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases, a pivotal question arises regarding the mechanisms through which specific neurodegenerative diseases manifest in individuals as they age. Taking AD as an illustrative example, its onset during the ageing process is influenced by multiple factors. According to the widely accepted Aβ cascade hypothesis,30 neuronal Aβ is physiologically produced. However, an imbalance between Aβ production and clearance throughout the ageing process results in cerebral accumulation of Aβ, thereby facilitating the onset of AD. Furthermore, a confluence of genetic predispositions and environmental influences collectively shapes an individual’s unique trajectory towards AD progression, with ageing serving as a catalyst in this complex interplay. Alternative hypotheses for AD have also been proposed, including but not limited to the tau protein hypothesis,31 abnormal lipid32 and glucose metabolism hypothesis,33 inflammation hypothesis,34 oxidative stress hypothesis (mitochondrial dysfunction),35 and the cholinergic hypothesis.36 These frameworks suggest that the pathophysiology of AD is characterized by phosphorylated tau accumulation and propagation,31 heightened inflammatory responses, dysregulation of oxidative stress (related to mitochondrial dysfunction),37 alongside a gradual decline in cholinergic function.38 Notably, these events are intricately linked to the ageing process and synergistically contribute to the pathogenesis of AD.

Therefore, it can be inferred from the above epidemiological evidence that ageing is an accelerator of neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 1). If we envision ageing as a flowing river, neurodegenerative disease is a boat navigating its waters. The flowing river increases the speed of the sailing boat. Comorbidities such as vascular diseases collide. Even if the oars stop moving, the boat continues to drift downstream as long as the river continues to flow. The analogy holds for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Even if pathological proteins such as Aβ, hyperphosphorylated tau, α-syn and TDP-43 accumulation in the brain are effectively cleared, cognitive decline persists as the brain ages and comorbidities continue to interact. Consequently, solely targeting neurodegenerative disease-specific pathologic changes may not be sufficient to achieve the desired outcomes. Halting or reversing the flow of a river would be an effective approach to prevent the boat from moving forwards or even to facilitate it to move backwards. Similarly, a comprehensive approach that prioritizes systemic rejuvenation, alongside interventions targeting disease-specific pathogenic events, constitutes a promising disease-modifying strategy to “press the pause button” on dementia progression.

Prevalence or incidence of neurodegenerative diseases by age. Epidemiological evidence indicates that ageing is an accelerator of neurodegenerative diseases. The prevalence of AD was based on the data of 2000 in the United States and Europe. The global prevalence of PD was based on the data from 1985 to 2010. The prevalence of ALS was based on the data of 2016 in the United States. The incidence of FTLD was based on the data of 2021 in Europe. AD Alzheimer’s disease, PD Parkinson’s disease, ALS Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, FTLD Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

Milestone events of studies on antiageing strategies

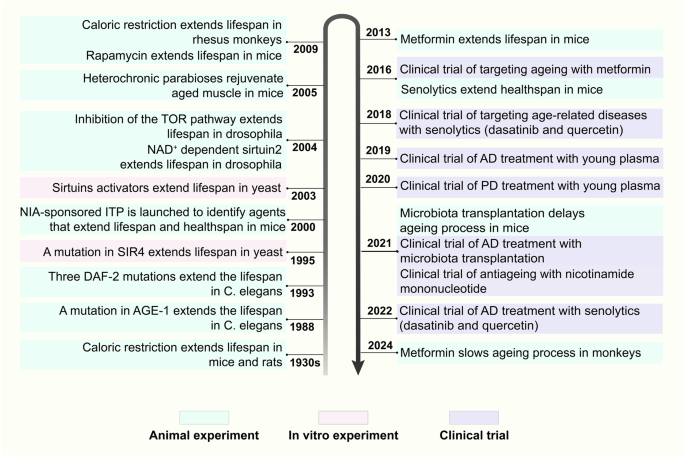

Significant breakthroughs have been made in the ageing and antiageing research fields; here, we review the research history and milestone events. As early as the 1930s, caloric restriction (CR) extended the lifespan of both mice and rats.39 Correspondingly, CR was found to prolong the healthy lifespan of rhesus monkeys in 2009.40 Since the mid-20th century, numerous ageing-related hypotheses and concepts have been proposed. In 1952, Peter Medawar et al. proposed the theory of ageing mutation accumulation, namely, that harmful mutations may continuously accumulate in an organism, eventually leading to ageing.41 In 1954, Denham Harman et al. proposed the free radical theory. In addition, he argued that reducing the production of free radicals could prolong the lifespan of mice by 20%.42,43 Then, George C. William et al. suggested the antagonistic pleiotropy theory that genes are favoured by natural selection if these genes exert beneficial effects on early fitness components as well as pleiotropic deleterious effects on late fitness components throughout life.44 Leonard Hayflick et al. discovered that the number of times a human cell can divide is limited, known as the “Hayflick limit” in 1961.45 Moreover, cellular senescence is defined as permanent growth arrest caused by endogenous and exogenous stress.45 Immunosenescence, a concept developed by Roy L. Walford et al. in 1969, is characterized by a decline in the body’s immune response to internal and external antigens.46 Later, in 1971, Alexey Olovnikov et al. pioneered the end-replication problem, which involves the loss of chromosome end fragments with each cell division, gradually shortening chromosomes.47 At the beginning of the 21st century, Claudio Franceschi et al. proposed the inflammageing theory.48 Moreover, the National Institute on Ageing (NIA) sponsored an intervention testing programme (ITP) to identify compounds that extend the lifespan of mice.49 A novel finding is emerging in this field: the awakening of endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) is a biomarker and powerful driver of cellular senescence and tissue ageing. In addition, targeting ERVs is a promising approach to alleviate ageing.50

In addition, many ageing-related genes and pathways have been identified. In 1988, AGE-1 mutation increased the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans by 40–60%.51 Similarly, the Daf-2 mutation doubled the lifespan of this species in 1993.52 Daf-2 inhibits insulin-like growth factor (IGF) intracellular signalling, which is involved in the regulation of blood glucose levels, suggesting that antiglucose drugs may interfere with ageing. In 2013, metformin prolonged the healthy lifespan of mice.53 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) subsequently approved the clinical trial Targeting Ageing with Metformin (TAME). Moreover, in 1995, a sirtuin 4 (SIR4) mutation in yeast extended the lifespan by more than 30%,54 after which SIRT1 was verified in mammals.55 In 2003, small-molecule activators of sirtuins (SIRTs) extended the lifespan of yeast by 70%.56 Additionally, inhibition of the target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway prolonged the lifespan in a 2004 study.57 In 2009, rapamycin, an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, was shown to significantly extend the lifespan of mammals.58 In 2004, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent sir2 was confirmed to extend the lifespan of Drosophila by 10–20%.59 Similarly, nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) is a direct precursor of NAD+, and the first clinical trial of NMN was conducted in 2021.60 A recent study demonstrated that metformin was capable of decelerating the ageing process of multiple organs in primates.61 In addition to these pathways, many transformations occur at the cellular level. In 1995, senescent cells were confirmed to exist and accumulate in human tissues with ageing, accompanied by senescence-associated secretory phenotypes (SASPs), which were proposed in 2008.62 In 2016, the elimination of senescent cells by senolytics in mice extended the healthy lifespan,63 and the first clinical trial was conducted in 2018.64 At the systemic level, the use of the young plasma to fight ageing was proposed early.65 In 2005, muscle regeneration and muscle stem cell viability in aged mice were restored by exposure to a young systemic environment.66

The concept of biological age emerged in the middle of the 20th century, specifically reflecting the degree of ageing of the structure and function of tissues/organs, and then, it was widely applied in the ageing research field.67 Supported by recent advances in high-throughput omics technologies, the first DNA methylation ageing clock was established in 2011 to assess biological age comprehensively and accurately.68 Later, the metabolomic ageing clock and transcriptomic ageing clock were published to explain ageing-related clinical traits.69,70 Steve Horvath et al. formally proposed the epigenetic clock in 2018. Genomic DNA methylation can be used to evaluate the methylation of a series of genetic loci and estimate the biological age.71

Antiageing strategies are increasingly being implemented in the context of AD and other neurodegenerative disorders. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that growth differentiation factor-11 (GDF11) in young plasma exerts neuroprotective effects by promoting neurogenesis within the hippocampus and enhancing learning and memory in aged mice.72 Two recent clinical trials involving young plasma infusion in patients with AD and PD, respectively, have further validated this intervention strategy for neurodegenerative diseases.73,74 Additionally, transplantation of young fecal microbiota has been shown to reverse age-related alterations in microglial activation while rejuvenating the metabolic profile of the hippocampus, primarily influencing amino acid metabolism. Furthermore, behavioural deficits were alleviated in older mice.75 Subsequent clinical trials have indicated that cognitive and behavioural improvements could be achieved through fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in patients with mild cognitive impairment as well as those suffering from PD.76,77 Moreover, clearance of senescent cells throughout the bodies of older mice led to a reduction in markers associated with neuronal senescence (such as LaminB1, P21, and High Mobility Group Box 1), reversal of age-related microglial activation and inflammation, enhancement of cognitive functions (including spontaneous activity and exploratory abilities), along with an extension of healthy lifespan among these older mice.63,78 The application of senolytics for patients diagnosed with early-stage AD has recently been investigated, yielding preliminary findings that suggest a potential role for these agents in managing neurodegenerative diseases.79,80

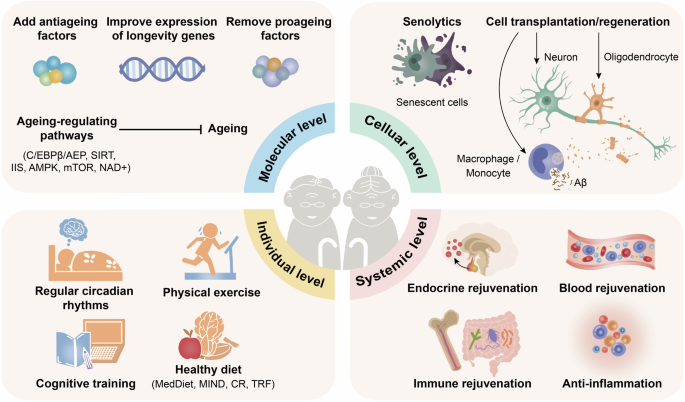

Physiological ageing and neurodegenerative diseases is inevitable and will continue to drive persistent research. In recent years, due to advances in high-throughput single-cell omics technologies and large-scale profiling,81 the research paradigm has shifted. The molecular features and mechanisms of ageing and neurodegenerative diseases have been analysed in unprecedented depth and comprehensiveness. These findings lay the foundation for subsequent studies on precise humoral markers of ageing and neurodegenerative diseases and effective targets for prevention and treatment (Fig. 2).

Milestone events in the history of antiageing research. This figure enumerates key events in the field of antiageing research and pivotal advancements in unitizing antiageing strategies to intervene neurodegenerative diseases from the 1930s onwards. NIA National Institute on Aging, ITP Intervention Testing Program, SIR4 sirtuin 4, NAD+ nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, TOR target of rapamycin, C. elegans Caenorhabditis elegans, AD Alzheimer’s disease, PD Parkinson’s disease

Complex systems view of ageing and neurodegenerative diseases

Ageing, neurodegenerative diseases and their comorbidities are characterized by a multifactorial and complex nature. According to the concepts of complex systems science, the human body is a self-organizing complex adaptive system (CAS), namely, a “network of networks”.82 These networks include horizontal connections among molecules, cells, organs, systems, and individuals, as well as vertical connections within each layer. Through the dynamic regulation of this high-dimensional and multiscale network, the human body actively and adaptively responds to internal or external stimuli to maintain homoeostasis, function and health.83,84 During ageing, adaptive responses are weakened due to deficits in the CAS network.83 When a stimulus is too intense and exceeds the regulatory capacity of the adaptive response or when the compromised adaptive response is insufficient to recover from stimulus-induced perturbations, homoeostasis is disrupted, leading to the onset of disease.83,84,85 The intricate nature of ageing substantiates that ageing constitutes a nonlinear dynamic process characterized by variability across different organs and systems.86

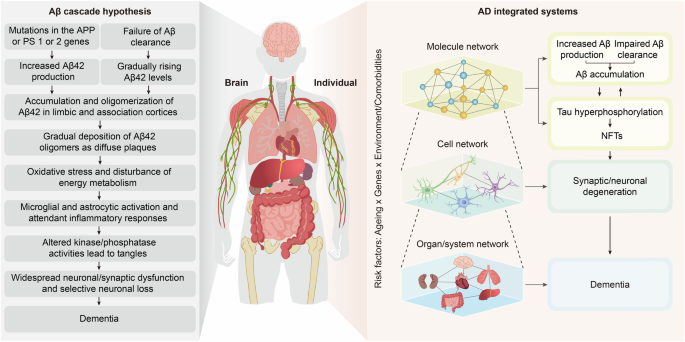

The concept of complex systems science is not foreign to neurodegenerative diseases. Take AD as an example (Fig. 3). The prevailing Aβ cascade hypothesis for AD suggests that an imbalance in the production and clearance of Aβ leads to its deposition. Aβ deposition initiates a series of downstream pathological events, such as tau pathology, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism disorders, ultimately resulting in synaptic or neuronal degeneration and eventually dementia.30,87 This linear hypothesis elucidates the major pathologic outcomes that arise from imbalances in homoeostasis at various scales, from the molecular to the cellular and ultimately to the organ layers, as well as the interconnections among them. In fact, the homoeostatic imbalances at each scale are a result of the dysregulated CAS. For example, Aβ deposition is the result of a homoeostatic imbalance between a continuous and intense stimulus (stressors leading to the overproduction or impaired clearance of Aβ) and an inadequate adaptive response (suppression of responses to inhibit the production or enhance the clearance of Aβ), as discussed below. Tau pathology is the result of an imbalance between tau phosphorylation and dephosphorylation induced by various triggers,88 principally Aβ. Neuronal degeneration involves increased amounts of neurotoxic molecules (e.g., Aβ, hyperphosphorylated tau, and inflammatory factors) and an insufficient supply of energy and neurotrophic factors,89,90 which are derived from various neural cells and tissues or organs other than the brain, as well as defective resistance or resilience of neurons to stressors.91

Overview of integrated systems involved in AD pathogenesis. AD was initially proposed to obey the Aβ cascade hypothesis, with Aβ as its core. Dysregulation of Aβ production and clearance leads to its accumulation, which further induces downstream oxidative stress, NFT formation, neuronal and synaptic degeneration, and ultimately dementia. Here, we propose viewing AD from the perspective of integrated systems. When intense stimulation exceeds the body’s resistance or when the resilience is insufficient to recover from the stimulus-induced disruption, homoeostatic imbalances result, as evidenced by Aβ and tau accumulation, synaptic/neuronal degeneration, and dementia. Genes, the environment and lifestyle are involved at every level. AD Alzheimer’s disease, APP amyloid precursor protein, Aβ amyloid-β, PS presenilin, NFTs neurofibrillary tangles. The figure was produced utilizing the applications Easy PaintTool SAI and Adobe Illustrator

Similarly, deficits in the CAS network also contribute to PD. PD is pathologically marked by intracellular aggregates of α-syn, known as Lewy bodies, and is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. Like Aβ deposition in AD, the abnormal aggregation of α-syn results from its overproduction (due to gene mutations, abnormal posttranslational modifications, and elevated oxidative stress) and the failure of α-syn clearance (due to proteasome and autophagy dysfunction). The degeneration of dopaminergic neurons is caused primarily by a combination of impaired proteostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction.92 These molecular and cellular stresses converge to trigger apoptotic and other cell death pathways, ultimately resulting in the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons and the manifestation of PD.

In addition, a defective CAS network is common in other neurodegenerative diseases. ALS, known as idiopathic fatal motor neuron disease, is characterized by the degeneration of both upper and lower motor neurons, leading to progressive muscle weakness, atrophy and eventual paralysis.93 FTLD, one of the most common types of dementia, is characterized by the degeneration and atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain and presents with early social–emotional–behavioural and/or language changes, accompanied by pyramidal or extrapyramidal motor neuron dysfunction.94 Although ALS and FTLD have different disease manifestations, many genetic and pathological mechanisms overlap. One specific pathology is the accumulation of TDP-43 within affected neurons. The aggregation of TDP-43 is due to its overproduction (due to SOD1, TDP-43 and FUS mutations) and the impaired cellular homoeostasis of motor neurons (e.g., mitochondrial function, axonal transport and RNA metabolism). Moreover, glial cells are actively involved in ALS/FTLD pathology in a noncell autonomous manner, affecting TDP-43 accumulation and subsequent neurodegeneration. For example, low levels of phagocytosis and autophagy, as well as the secretion of inflammatory factors by microglia, are associated with the noncell-autonomous toxicity of astrocytes.95 Furthermore, HD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder with a distinct phenotype, including chorea and dystonia, incoordination, cognitive decline, and behavioural difficulties.96 The pathogenesis of HD primarily stems from an abnormally expanded CAG repeat near the N-terminus of the Huntingtin gene, resulting in the production of mutant HTT (mHTT) protein. This aberrant protein forms toxic aggregates, which further disrupts the protein degradation system, axonal transport, and mitochondrial function. Additionally, glial cell activation synergistically contributes to neurodegeneration.97,98

Overall, the development of neurodegenerative disorders does not result from a single molecule or cell but rather from an emergent homoeostatic imbalance within CAS. The integrated systems perspective provides a comprehensive approach to understanding the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Understanding these interconnected processes is essential for developing effective strategies to prevent and treat age-related neurodegenerative diseases.

Systemic regulatory mechanisms of ageing in neurodegenerative diseases

In this section, we discuss the impacts of ageing on neurodegenerative diseases from the perspective of complex systems.

Molecular and cellular networks of ageing in neurodegenerative diseases

Changes in the ageing brain

Brain ageing involves multidimensional and multilevel changes in molecules, cells, neural circuits, tissues, and brain functions. The hallmarks of ageing have been newly refined and include genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, disabled macroautophagy, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, altered intercellular communication, chronic inflammation and dysbiosis.85 The hallmarks of brain ageing are broadly consistent with these hallmarks, but specific characteristics have been identified, such as aberrant neural network activity and glial cell activation.99 This section summarizes the hallmarks of brain ageing based on these aspects.

Molecular level

Brain ageing involves several critical molecular changes that collectively contribute to cognitive decline and increased susceptibility to neurodegenerative diseases. One of the hallmarks of brain ageing is the elevated levels of oxidative stress.100,101 The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) increases, leading to oxidative damage to cellular components such as DNA, proteins, and lipids. The efficiency of DNA repair mechanisms decreases with age, leading to the persistence of DNA lesions.102 These impairments can disrupt gene expression and cellular function. Changes in DNA methylation, histone modification, and noncoding RNA expression have also been observed and affect gene expression profiles in ageing neurons.103,104 Chronic sterile low-grade inflammation, often referred to as “inflammageing” is another significant molecular feature. Glial cells in the brain, such as microglia and astrocytes, become chronically activated and release proinflammatory cytokines.105 Mitochondrial function deteriorates with age, resulting in decreased ATP production and increased ROS generation.106 Mitochondrial DNA mutations accumulate, further impairing cellular energy metabolism and promoting apoptotic pathways.107 Additionally, the process of brain ageing is accompanied by the accumulation of misfolded proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as deposition of Aβ and α-syn, accumulation of hyperphosphorylation of tau (i.e. primarily ageing-related tauopathy, PART),108 and pathology of TDP-43 (i.e. limbic predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, LATE).109

The nutrient-sensing network is highly conserved throughout evolution and is deregulated during ageing. The insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signalling (IIS) pathway is the first identified and extensively validated age-regulating pathway.110 IGF-1 is expressed in neurons and glial cells in a brain region-specific manner and has a neuroprotective effect by promoting synaptogenesis and neurotrophin signalling,111 counteracting oxidative stress and inflammation, and modulating neuronal excitability.112 However, during ageing, a decrease in the activity of IGF-1 occurs, which manifests as deficiency and resistance, and exacerbates age-related changes in the brain.113,114,115 In addition, mTOR, known as a modulator of key cellular processes, participates in the activation of protein synthesis, biomass accumulation and the repression of autophagy.116 The activity of mTOR in the brain increases with age,117 substantially inhibiting autophagy, which could explain why pathological proteins are prone to accumulation.118 Furthermore, seven mammalian SIRTs, namely, sirtuin1 to sirtuin7, have been identified. SIRTs are involved in various biological processes, including inflammation, glucose and lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, and autophagy.119 SIRT1, one of the most valuable targets, deacetylates protein substrates to exert neuroprotective effects, maintaining neural integrity.120 SIRT1 transcription decreases in the aged brain,121 worsening pathological protein aggregation and neuron loss and sharply increasing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases.122,123 Similarly, alterations in other ageing-related pathways, such as adenosine 5’-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and NAD+, with ageing also contribute to neurodegeneration.124,125 Notably, these pathways do not act singly but rather interact with each other to regulate ageing and ageing-related diseases. For example, SIRT1 downregulates the mTOR pathway and upregulates the AMPK pathway, synergistically enhancing autophagy.126

Cellular level

The accumulation of molecular changes leads to structural and functional alterations in various brain cells. Neuronal dendrites, which receive synaptic inputs, can retract and lose their complexity, reducing the number of synaptic connections.127 A reduction in synaptic density has been observed, which impacts neural communication. Ageing-related pigments, such as lipofuscin, accumulate within neurons. Functionally, the synthesis and release of neurotransmitters (e.g., acetylcholine, dopamine, and glutamate) and neurotrophic factors (e.g., NGF and BDNF) decrease.128 Neuronal excitability and plasticity decline, and metabolic activity, such as ATP production, is reduced.129 Additionally, senescent cells and SASPs accumulate in the ageing brain to drive neurodegeneration.130

Brain ageing also involves functional and structural changes in various glial cells. The process of brain ageing is characterized by inflammation, with microglia serving as crucial immune regulatory cells in the brain, indicating their significant role in this process. The states of microglia, such as telomerase activity,131 morphology and distribution pattern,132 degree of activation,133 cell migration and the speed of the response to inflammation,134 significantly change with ageing. During the ageing process, there is a significant increase in neurotoxic M1 microglia, accompanied by a concomitant decrease in neuroprotective M2 microglia. This imbalance leads to the production of substantial quantities of pro-inflammatory factors, chemokines, and reactive substances, collectively exacerbating neuroinflammation.135 The initial identification of disease-associated microglia (DAM) occurred in the brain tissue of AD transgenic mice,136 with subsequent research indicating that the prevalence of DAM cells increases with age. High-dimensional cytometry revealed that approximately 11.9% of microglia in aged mice were classified as DAM, while no DAM cells were detected in young mice.137 High-throughput sequencing revealed that the expression of genes related to cell migration and cytoskeletal protein homoeostasis in aged microglia changed significantly,138 explaining the decrease in microglial migration caused by ageing. Moreover, microglia are the main cells responsible for the clearance of pathological substances and cell debris in the brain, but this clearance capacity decreases significantly with ageing.139

Astrocytes play an indispensable role in maintaining the homoeostasis of the nervous system. Changes in the gene expression and structure of astrocytes are early events in brain ageing.140,141 During the ageing process, astrocytes exhibit ageing-related phenotypes, such as an increased stress response, reduced telomere length and mitochondrial activity,142 and their ability to maintain neuronal activity and promote the proliferation of neural precursor cells is also significantly reduced.143,144 Under inflammatory conditions, astrocytes may be transformed into the neurotoxic A1 state or the neuroprotective A2 state.145 During ageing, astrocytes spontaneously transform into a neurotoxic A1 state,146 which in turn causes neuronal dysfunction. The regulatory mechanism underlying this transformation needs to be further explored. As astrocytes regulate homoeostasis in the central nervous system (CNS), changes in the astrocyte states may directly impair neuronal function and ultimately lead to the occurrence of various neurodegenerative diseases.

Oligodendrocytes are located in the white matter of the brain and protect the integrity of axons by forming myelin structures on the surface of neuronal axons. Consistent with astrocytes, as the brain ages, changes in gene expression in oligodendrocytes precede those in neurons and microglia,140 and their dysfunction may increase the vulnerability of neurons to ageing-related pathogenic risk factors. Ageing is often accompanied by a demyelination process, which is associated with increased levels of DNA oxidative damage in aged oligodendrocytes.147 The myelinogenesis and remyelination capacities of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) also decrease.148

The blood‒brain barrier (BBB) is a critical structure that protects the brain by regulating the entry of substances from the bloodstream into neural tissue. The BBB also functions as part of the neurovascular unit (NVU), which is composed of astrocytes, microglia, specialized endothelial cells, pericytes, and the basement membrane of the BBB. The endothelial cells that line the blood vessels in the brain become less effective with age. An increase in the permeability of these cells can lead to a compromised barrier.149 The basement membrane, which supports endothelial cells, also undergoes thickening and structural alterations.150 These changes compromise the structural integrity of the barrier. The expression and functionality of proteins that form tight junctions between endothelial cells, such as occludin and claudin, are reduced.151,152 The structure and function of the BBB also undergo significant alterations with ageing, which contribute to the progression of neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive decline.153 A key change is the increased permeability of the BBB.154 The enhanced permeability facilitates the easier entry of potentially detrimental substances, such as toxins and pathogens, into the brain. The process of ageing is associated with a state of low-grade chronic inflammation, which further compromise the integrity of BBB, leading to increased permeability and more significant damage. The glymphatic system, a crucial transportation mechanism, facilitates the clearance of metabolic waste and misfolded proteins within the brain. This system is comprised of three distinct components: the periarterial space, the perivenous space, and the interstitial space in brain parenchyma. The expression of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) in astrocytes significantly influences the transport and clearance functions of the glymphatic system.155 As individuals age, there is a decline in the efficiency of these transport mechanisms in eliminating waste products such as Aβ.156,157 This inefficiency contributes to the accumulation of neurotoxic substances within the brain during ageing.

Notably, changes in various brain cells during ageing are not independent events. In contrast, these cells closely interact with each other through cell‒cell cross talk and jointly promote brain ageing and brain ageing-related neurodegeneration. For example, demyelination is an early sign of brain ageing, and shed myelin sheaths can accumulate in microglia, leading to microglial ageing and dysfunction.158 Senescent microglia actively secrete proinflammatory cytokines, which further leads to activation of astrocyte and neuronal apoptosis.145 The current understanding of the ageing hallmarks in various brain cells is comprehensive; therefore, exploring the characteristics of altered intercellular communication during ageing should be considered as a prospective avenue for future research.

Tissue or organ level

The accumulation of cellular changes gradually leads to alterations in brain structure. Changes in brain volume and structure are significant characteristics of brain ageing. One of the most notable structural changes in the ageing brain is thinning of the cerebral cortex.159 Studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have consistently shown a reduction in cortical thickness with age.160 This thinning is particularly evident in the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive functions such as decision-making, problem-solving, and planning.161 Ageing is associated with a decrease in grey matter volume, which consists of neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and synapses. The reduction in the grey matter volume is more pronounced in regions such as the hippocampus, which plays a critical role in memory and learning.162 The white matter, which contains myelinated axons, also undergoes significant changes. The white matter integrity undergoes a general decline, characterized by decreases in both myelin density and quality.163 This degradation can lead to slower neural signal transmission and impaired connectivity between different brain regions.

Neuronal circuit level

Functional connectivity between different brain regions changes with age. A decrease in the strength of long-range connections, particularly between the frontal and parietal lobes, often occurs.164 Imaging studies have revealed a decrease in the fraction of action-plan-coding neurons and the action plan signal of individual neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), leading to impaired working memory coding and recurrent connectivity.165 Conversely, an increase in local connectivity may be present within certain regions, which can lead to less efficient information processing. The cognitive function arises from the dynamic interactions occuring within extensive brain networks. Studies have shown that intranetwork connectivity decreases while extranetwork connectivity increases with age, diminishing the integrity of many large-scale networks.166 The default mode network (DMN), which is active during rest and is involved in self-referential thinking, shows altered activity patterns with ageing. Older adults often exhibit decreased deactivation of the DMN during task performance, which is thought to contribute to attentional deficits.167 The circuitry of the hippocampus, crucial for memory formation, undergoes alterations. A decrease in the functional connectivity between the hippocampus and other brain regions, such as the prefrontal cortex, has been observed.168 These disruptions can impair the encoding and retrieval of memories. Disruptions in primary information processing networks, such as auditory, visual, and sensorimotor networks, may lead to the overactivity of multisensory integration networks and the accumulation of pathological proteins, contributing to the development of dementia.169 Ageing also affects various neurotransmitter systems, including those involving dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. The activity of dopaminergic circuits, specifically, exhibits a decline, thereby potentially impacting motor control and executive functions.170

Functional level

The cumulative alterations occurring at the aforementioned levels during the process of ageing ultivately result in impairments in brain function, which serve as the basis of various neurodegenerative diseases. Brain functions, including cognition, motor coordination, sensory perception, and emotion, are affected by ageing. Ageing is strongly associated with a decline in cognitive functions, including memory, executive function, processing speed, and attention. Episodic memory and working memory are particularly susceptible to age-related decline, which adversely affects an individual’s capacity for acquiring new information and excuting intricate cognitive tasks.171 The decline in fine motor ability is consistently observed with advancing age,172 making it a reliable indicator for predicting brain ageing. Additionally, emotional changes, such as age-related anxiety and depression, are prevalent in ageing populations.173,174

In conclusion, the hallmarks of brain ageing involve multiple factors, ultimately leading to a decline in overall nervous system function. These hallmarks provide a crucial basis for assessing the degree of brain ageing and for the prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.175

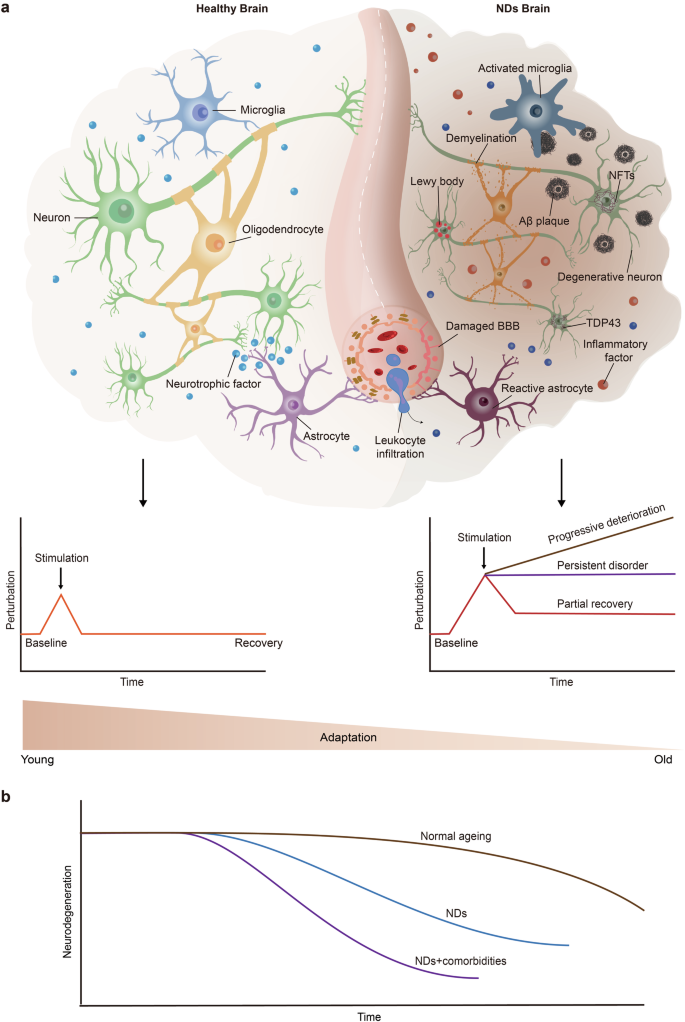

Regulatory mechanisms of brain ageing in neurodegenerative diseases

Brain ageing is the principal risk factor for a spectrum of neurodegenerative diseases. It precipitates the onset of these conditions through a convergence of cellular and molecular processes, notably oxidative stress, inflammation, disrupted proteostasis, synaptic dysfunction, compromise BBB integrity, genetic predisposition, and cellular senescence. Although ageing constitutes a unifying factor in neurodegeneration, each disorder manifests distinct pathological and molecular signatures. AD ranks among the most prevalent neurodegenerative conditions. Accordingly, our focus lies in elucidating the molecular and cellular mechanisms through which brain ageing influences AD. Additionally, we delineate ageing-associated mechanisms pertinent to other neurodegenerative disorders, such as PD, ALS, and HD (Fig. 4).

Schematic diagram of the decline in brain adaptation during ageing and neurodegenerative diseases. a Young and healthy brains can actively respond to various stimuli, thus maintaining homoeostasis and normal brain function. During ageing, the compromised adaptation of the brain is insufficient to recover from stimulus-induced perturbations, resulting in a homoeostasis imbalance and the development of disease. b In the brains of neurodegenerative disease patients, pure neurodegenerative disease pathology is relatively rare and is often accompanied by other pathological changes, such as vascular damage and the aggregation of pathological proteins (e.g., TDP43 and Lewy bodies). Once these comorbidities occur, cognitive decline appears earlier, progresses more rapidly, and reaches lower levels. NDs neurodegenerative diseases, Aβ amyloid-β, BBB blood–brain barrier, NFTs neurofibrillary tangles, TDP43 transactive response DNA binding protein 43. The figure was produced utilizing the applications Easy PaintTool SAI and Adobe Illustrator

Brain ageing and AD

Brain ageing and AD share common alterations, such as a loss of proteostasis, oxidative stress, and inflammation, which are exacerbated in AD.99 These alterations are caused by cellular dysfunction and involve almost all types of neural cells. The neurons serve as the principal site for Aβ production and NFT formation, which are fundamental to cognitive impairment. The amyloidogenic processing of APP primarily involves the activities of β- and γ-secretases, both of which are upregulated in neurons during ageing.176 Conversely, the activity of Aβ-degrading enzymes such as neprilysin and insulin-degrading enzymes decreases,177 thereby promoting cerebral Aβ accumulation. Microglia are the primary immune cells in the brain that clear pathological and redundant substances such as Aβ. However, the phagocytosis of Aβ is defective in aged microglia.178 Astrocytes play a crucial role in providing neurons with energy and neurotrophic factors, while also being involved in the regulation of the BBB funciton and inflammatory processes.179 The process of ageing in astrocytes results in neuronal energy and nutrient deficiency, an augmented SASP and BBB permeability.90 Furthermore, oligodendrocytes provide energy and nutrients for neuronal axons and protect them from injury. The loss of myelin integrity with ageing has been reported to promote Aβ formation and neuronal degeneration in animal models.180 Cerebral vessels, especially microvessels are responsible for the exchange of substances between the brain and the blood. The integrity and functionality of the BBB and the lymphatic system are contingent upon the structural characteristics and operational dynamics of cerebral blood vessels.149,155 The permeability of the BBB increases and the transport capacity of the glymphatic system diminishes during the process of age, facilitating the accumulation of Aβ and other pathological substances in the brain.181,182

Importantly, brain cells do not function independently but interact in the form of cellular networks such as neurovascular units. During the process of brain ageing, the concurrent decline in both the structure and function of these neural cells, along with the presence of comorbidities, results in an imbalance between the stimulation and adaptive responses of the CAS, leading to accumulation of Aβ and tau proteins, neurodegeneration, and ultimately dementia. Thus, the role of age-related alterations in intercellular communication in the AD pathogenesis is worthy of investigation.

Furthermore, instances of concurrent pathologic changes are prevalent in elderly individuals, whereas pure AD represents an exception. The most common comorbidities that underlie cognitive impairment include pathologic changes associated with cerebrovascular and other concomitant neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Lewy bodies, TDP-43, and hippocampal sclerosis). Data from the Religious Orders Study/Memory and Ageing Project (ROS/MAP) cohort revealed that approximately 97% of persons diagnosed with probable AD had other concomitant neurodegenerative or vascular comorbidities, including microinfarcts or any of the vessel diseases that are also commonly present and contribute to cognitive impairment, whereas more than 86% of older persons without cognitive impairment had vascular, AD or other degenerative comorbidities in the brain.183 These comorbidities are also affected by ageing and promote the progression of AD and dementia.

Brain ageing and PD

Several major molecular hallmarks of brain ageing overlap with mechanisms implicated in PD neurodegeneration, including oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, a loss of protein homoeostasis, neuroinflammation, genomic instability, and impaired stress responses. Among them, mitochondrial dysfunction and bioenergetic failure have been implicated as primary mechanisms for the development of PD. This finding is supported by the identification of reduced levels of complex I in dopaminergic neurons of PD patients,184 and reinforced by recent studies on familial PD-linked genes such as,leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), Parkin, synuclein alpha (SNCA), and DJ-1, as well as PD-like phenotypes resulting from genetic deletion of a catalytic ETC complex I subunit.184,185,186,187 Dopaminergic neurons are more vulnerable to the age-related loss of mitochondrial function, resulting in bioenergetic stress due to their highly ramified processes that harbour dense mitochondria to sustain energy-requiring processes at distal sites.188 Ageing is a critical factor contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction, a pivotal event in the pathogenesis of PD. As cells age, mitochondrial DNA accumulates mutations, and the efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation decreases.189 These changes lead to increased production of ROS, causing oxidative stress and damage to cellular components, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. Furthermore, ageing impairs the mitophagy process, reducing the clearance of damaged mitochondria and exacerbating cellular stress.190 These vulnerabilities are particularly pronounced in the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra due to their high metabolic demand and reliance on mitochondrial function. The convergence of these ageing-related mitochondrial impairments contributes significantly to the neurodegenerative processes observed in PD patients, highlighting the importance of maintaining mitochondrial health as a potential therapeutic avenue for mitigating disease progression.

Brain ageing and other neurodegenerative diseases

In addition to AD and PD, ALS, FTLD and HD are also prominent neurodegenerative disorders. This section provides a concise overview of the ageing mechanisms implicated in ALS, FTLD, and HD, with a specific focus on how the process of ageing influences their distinct pathological progression.

Unlike AD and PD, ALS is a relatively rare neurodegenerative disease with a global prevalence of approximately 1.57–11.80 per 100,000 individuals.191 The average age of onset is 55 years. Ageing intersects with unique molecular mechanisms in ALS that differentiate it from other neurodegenerative conditions. One distinguishing characteristic is the preferential susceptibility of motor neurons to protein aggregation. Mutations in genes such as SOD1, TDP-43, and FUS lead to the formation of toxic protein aggregates specifically within motor neurons.192 The cellular capacity for efficient trafficking and clearance of misfolded proteins diminishes with age, resulting in the accumulation of toxic proteins and hastening the demise of motor neurons. Furthermore, ALS is characterized by aberrant RNA processing and nucleocytoplasmic transport defects, which are often linked to mutations in C9orf72 and other RNA-binding proteins.193 Ageing-related changes in the expression and activity of splicing factors can further impair RNA processing. Unlike other neurodegenerative diseases, ALS also results in pronounced disturbances in the axonal transport and cytoskeletal dynamics of motor neurons.194 These molecular abnormalities, coupled with age-related decreases in cellular repair mechanisms, result in the progressive degeneration of motor neurons, underscoring the unique interplay between ageing and ALS pathogenesis.

FTLD, which shares some of the pathological and genetic mechanisms with ALS, is also a common form of dementia, with a prevalence ranging from 1 to 461 per 100,000 people.195 The majority of FTLD cases arise from mutations in genes encoding microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT), progranulin (GRN), and C9orf72, whereas the remaining FTLD cases are caused primarily by mutations in genes encoding FUS, TDP-43, valosin-containing protein (VCP) and charged multivesicular body protein 2B (CHMP2B). These mutations are associated with defective autophagic clearance and lysosomal function.196 Autopsy evidence revealed that the brains of the elderly population are more susceptible to TDP43 accumulation.197 Additionally, brain ageing is accompanied by lysosomal dysfunction and neuroinflammation,198 which collectively accelerate the occurrence and development of FTLD.

HD is a relatively rare neurodegenerative disease, with an average prevalence of 4.88 per 100,000 individuals.199 HTT gene mutations trigger a cascade of molecular events, including transcriptional dysregulation, impaired protein homoeostasis, and disrupted intracellular transport.200 These abnormalities are compounded by age-related decreases in cellular repair mechanisms and increased oxidative stress. Unlike other neurodegenerative diseases, HD specifically affects the striatum and cortex, leading to characteristic motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms. Thus, the interplay between ageing and the unique genetic and molecular landscape of HD drives its distinct pathogenesis.

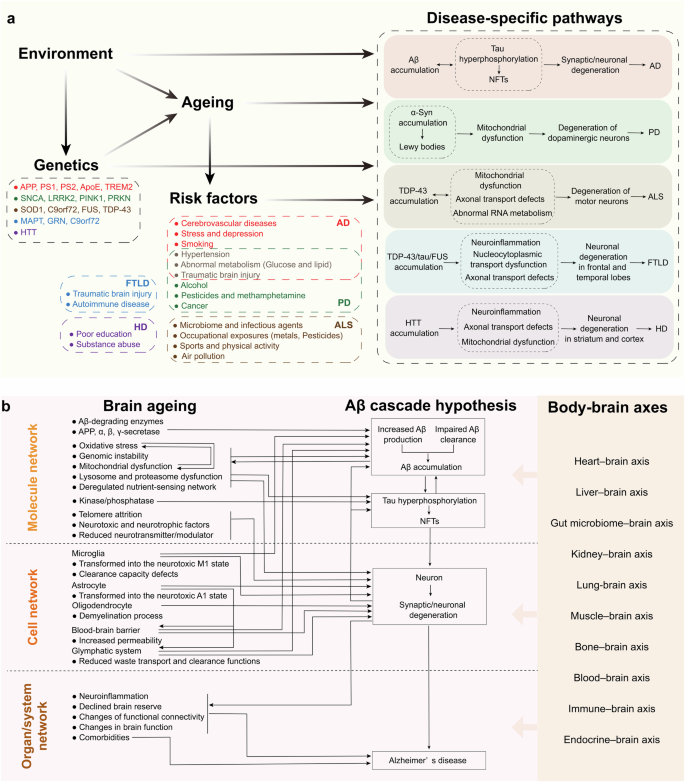

Ageing is a holistic non-specific process that nevertheless promotes specific types of neurodegenerative diseases in different individuals. Ageing is regulated by both environment and genetic factors (wherein the latter are also subject to environment). As well, ageing exerts an effect on the specific risk factors associated with different neurodegenerative diseases. The four aforementioned aspects act in a synergistic manner on the specific mechanisms and pathways of neurodegenerative diseases. The molecular, cellular, and systemic regulatory mechanisms of brain ageing significantly contribute to the development and progression of various neurodegenerative diseases. Key mechanisms encompass genetic factors, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, proteostasis disruption, protein aggregation, synaptic plasticity impairment, and cellular senescence. Collectively, these mechanisms modulate specific pathways involved in neurodegenerative diseases. In the context of AD, brain ageing processes play a crucial role in neuronal degeneration and disease progression through their pleiotropic impact on AD-specific pathologies (such as amyloid-beta accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation) as well as common age-related changes (Fig. 5). Understanding these intricate mechanisms provides essential insights into potential therapeutic strategies aimed at mitigating the effects of ageing on the brain and slowing down the progression of neurodegenerative disorders.

Specific mechanisms by which ageing promotes different neurodegenerative diseases. a Ageing promotes specific neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing is a holistic non-specific process that nevertheless facilitates the emergence of distinct types of neurodegenerative diseases in different individuals. Ageing is co-regulated by both environment and genetic factors (wherein the latter are also subject to environment). As well, ageing exerts an effect on the specific risk factors associated with different neurodegenerative diseases. The interplay between environmental and genetic factors co-regulates ageing, with the latter also being influenced by environmental conditions. Furthermore, ageing impacts the specific risk factors associated with different neurodegenerative diseases. These four aforementioned aspects synergistically interact with the unique mechanisms and pathways underlying neurodegenerative diseases. b Brain ageing acts on the AD pathway. During brain ageing, molecular, cellular, and tissue/systemic networks undergo profound transformations that promote specific pathways conducive to various neurodegenerative diseases. For example, AD is characterized by Aβ accumulation, which occurs alongside age-related comorbidities leading to neuronal degeneration and AD progression. In the context of brain ageing, Aβ-degrading enzymes and amyloidogenic processing of APP directly affect both Aβ production and clearance rates. Key hallmarks of ageing include oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunctions, genomic instability, proteasome and lysosomal dysfunctions as well as nutrient perception disorders; these factors collectively enhance Aβ deposition. Additionally, age-related reductions in microglial activity and transport systems such as the blood-brain barrier and glymphatic system impair Aβ clearance efficiency. The accumulation of Aβ triggers downstream formation of NFTs, further exacerbating hallmark features associated with ageing while concurrently diminishing neuroglial support for neurons, this combination accelerates neuronal degeneration linked to AD pathology. Moreover, neuroinflammation along with alterations in structural integrity and functional capabilities within an ageing brain contribute significantly to AD pathogenesis; peripheral organ ageing also plays a role in influencing AD progression through direct effects on Aβ dynamics as well as indirect effects on brain ageing. APP amyloid precursor protein, PS presenilin, ApoE Apolipoprotein E, TREM2 triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2, SNCA synuclein alpha, LRRK2 leucine-rich repeat kinase 2, PINK1 PTEN-induced putative kinase 1, PRKN parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein Ligase, SOD1 superoxide dismutase 1, C9orf72 chromosome 9 open reading frame 72, FUS fused in sarcoma, TDP-43 transactive response DNA binding protein 43, MAPT microtubule associated protein tau, GRN granulin, HTT huntingtin, AD Alzheimer’s disease, PD Parkinson’s disease, ALS Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, FTLD Frontotemporal lobar degeneration, HD Huntington’s disease, NFTs neurofibrillary tangles, Aβ amyloid-β, α-syn α-synuclein

Body‒brain axes in relation to ageing and neurodegenerative diseases

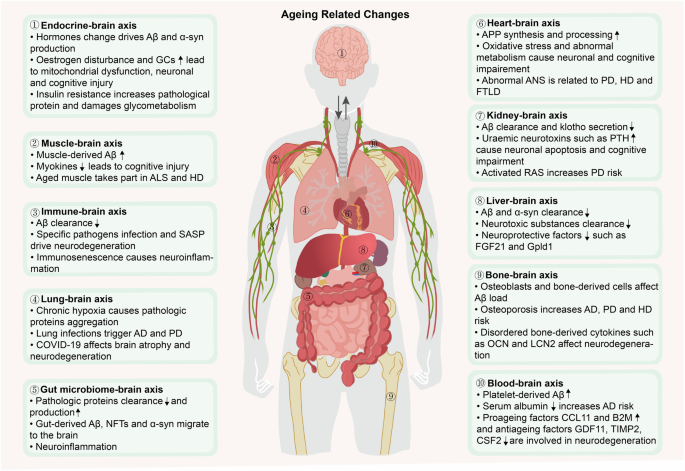

The brain, serving as the central hub of the body, not only governs the activities of peripheral tissues and organs but also undergoes reciprocal influences from them, establishing a crucial network of interconnected organs and systems that uphold overall bodily function. Emerging evidence indicates that the ageing of peripheral organs contributes to brain ageing and the development of neurodegenerative diseases.201 Recent investigations propose that ageing constitutes a nonlinear dynamic procedure demarcated by heterogeneity among diverse organs and systems.86,202 This finding underscores the complex nature of ageing, indicating that interventions should be approached from a holistic perspective. Here, we aim to introduce the concept of body‒brain axes in relation to ageing and neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 6).

The impacts of the body‒brain axis ageing on neurodegenerative diseases. The brain interacts with multiple peripheral organs, and the functions and structures of peripheral organs change with age, leading to a decline in their support of the brain. Aged peripheral organs interfere with pathological proteins accumulation, neuronal activity and other brain functions, ultimately promoting the dysregulation of brain homoeostasis and the occurrence of neurodegenerative diseases. FSH follicle-stimulating hormone, Aβ amyloid-β, GCs glucocorticoids, SASP senescence-associated secretory phenotype, AD Alzheimer’s disease, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, NFTs neurofibrillary tangles, APP amyloid precursor protein, PTH parathyroid hormone, FGF21 fibroblast growth factor 21, Gpld1 glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase D1, OCN osteocalcin, LCN2 lipocalin-2, CCL11 C-C motif chemokine ligand 11, B2M β2-microglobulin, GDF11 growth differentiation factor 11, TIMP2 tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2, CSF2 granulocyte‒macrophage colony stimulating factor, PD Parkinson’s disease, α-syn α-synuclein, ALS Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, HD Huntington’s disease, FTLD Frontotemporal lobar degeneration, ANS autonomic nervous system, RAS renin–angiotensin system. The figure was produced utilizing the applications Easy PaintTool SAI and Adobe Illustrator

Heart‒brain axis

At rest, the adult brain typically receives approximately 15 to 20% of the cardiac output to ensure a sufficient supply of energy and oxygen. However, the ageing process results in decreases in the ejection fraction and the portion of cardiac output allocated to the brain,203 as well as the contraction of the cerebral vasculature, which jointly result in chronic brain hypoperfusion (CBH).204,205 Additionally, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) of the heart in the elderly experiences pathological oscillations, leading to myocardial electrophysiological changes and defective activation and recovery of the myocardium, resulting in a loss of the ability to regulate the heart rate and rhythm of the heart.206 A recent study established the biological age (BA) of multiple human organ systems using data from the UK Biobank and revealed that cardiovascular age has the strongest influence on brain age, with a 1-year increase in the cardiovascular age increasing the brain BA by 27 days.207

The progression of age-related heart changes plays a pivotal role in the onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases. AD patients often exhibit lower ejection fractions, lower cerebral blood flow velocities, and greater vascular resistance.208,209 CBH during ageing has been widely reported to contribute to AD pathogenesis.210 CBH directly enhances the synthesis and amyloidogenic processing of APP by increasing the activities of β-secretase and γ-secretase to produce Aβ.211 Additionally, CBH disrupts the integrity of BBB, impairing the clearance of Aβ from the brain via transcytosis. Furthermore, cerebral ischaemia and hypoxia due to CBH disrupt neuronal energy metabolism and lead to acidosis and oxidative stress, ultimately causing neuronal degeneration and cognitive impairment in an Aβ-independent manner.212 On the other hand, the elderly heart is prone to chronotropic insufficiency, and the inability to regulate heart rate is affected by the ageing ANS.213 This change is considered an early sign of PD214 and HD,215 as well as one mechanism of cognitive decline in elderly women.216 The measurement of vascular risk may serve as a valuable tool for the early diagnosis of patients with PD or the identification of those individuals who are at high risk, thereby confirming the potentially intricate relationship between cardiac health and PD.217 In addition, alterations in heart rate and the ANS are related to atrophy of the mesial temporal cortex, insula, and amygdala, as well as energy homoeostasis, which is prevalent in FTLD.218

Liver‒brain axis

The liver plays important roles in regulating metabolism and degrading metabolic wastes or poisons from the blood, thus maintaining brain and whole-body homoeostasis. Studies in humans have revealed that liver function decreases with age, as indicated by increased serum γ-glutamyl transpeptidase and alanine aminotransferase levels.219 Liver biopsies from older adults revealed that the degree of liver ageing is related to the severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD),220 which increases the brain age by approximately 4.2 years.221 In addition, the liver secretes neuroprotective molecules such as fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase D1 (Gpld1), which are reported to prevent neuronal apoptosis,222 improve neurogenesis223 and even prolong the lifespan of mice.224 The aged liver secretes fewer neuroprotective molecules and eliminates fewer neurotoxic substances (e.g., superoxide radicals), exacerbating the accumulation of excessive oxidation products in the brain.225

The aged liver mainly participates in the clearance of excessive brain-derived misfolded proteins, thereby driving the pathological events of neurodegenerative diseases. The liver clears approximately 60% of circulating Aβ.226 However, this capacity decreases with age, which is partially attributed to the low expression of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1) in hepatocytes.227,228,229 In addition, hepatic soluble epoxide hydrolase activity increases with age, decreasing the brain level of 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid, which directly binds to Aβ to prevent its deposition and indirectly enhances microglial TREM2-dependent Aβ phagocytosis, further delaying cognitive decline.230 In PD, brain-derived α-syn accumulates in the livers of both mice and humans; thus, the liver may participate in the clearance and detoxification of α-syn,231 suggesting that a decrease in aged liver function increases α-syn deposition in the brain. Furthermore, deficits in toxin clearance in aged livers increase the concentrations of circulating toxic substances, especially citrulline and ammonia, which may accelerate the onset of HD.232

Gut microbiome‒brain axis

The gut microbiome primarily regulates brain homoeostasis through the vagus nerve, endocrine system, immune system and transmission of metabolites.233 The microbiota and its metabolites are altered during ageing; for example, the abundance of the anti-inflammatory bacterium Faecalibacterium decreases, whereas that of proinflammatory Fusobacterium increases, leading to intestinal inflammation.234 The gut microbiota derived from old rats facilitates brain ageing in young rats; this effect manifests as modifications in synaptic structure and increased levels of advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs), which are markers of ageing.235

Microbial dysbiosis during ageing is undeniably linked to the metabolism of multiple pathogenic proteins. First, it is implicated in the release of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and bacterial amyloid protein.236 The bacterial amyloid protein may induce Aβ accumulation via a prion-like seeding mechanism.237 In addition, LPS impedes Aβ clearance by increasing the vascular sequestration of Aβ, reducing the bulk flow of cerebrospinal fluid and impairing Aβ transport across the BBB.238 Moreover, LPS induces the formation of a distinct type of α-syn fibrils, similar to the pattern of wild-type α-syn fibril induction commonly observed in individuals with PD.239 As early as 2003, human autopsy evidence first revealed that intestinal α-syn could retrogradely diffuse from the vagal nerve to the substantia nigra and destroy dopaminergic neurons.240 Correspondingly, truncal vagotomy prevents the spread of α-syn from the gut to the brain, which is associated with neurodegeneration and behavioural deficits.241,242 Additionally, peripheral LPS promotes TDP-43 mislocalization and aggregation, contributing to TDP-43 proteinopathies in neurodegenerative disorders, such as FTLD and ALS.243 Second, intestinal inflammation may activate the CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein (C/EBPβ)/asparagine endopeptidase (AEP) pathway. This pathway is responsible for mediating the cleavage of APP and tau proteins, resulting in the formation of pathological fragments (e.g., APP C586 and tau N368) that promote Aβ and NFT formation, which are transmitted to the brain through the vagus nerve.244 In addition, activated C/EBPβ inhibits the expression of BDNF and netrin-1, leading to α-syn aggregation and dopaminergic neuronal loss.245 Eventually, microbial dysbiosis triggers chronic systemic inflammation, disrupting the BBB and exacerbating neuroinflammation and the progression of neurodegenerative diseases.246,247,248

Kidney–brain axis

The kidneys are responsible for eliminating harmful circulating substances, preventing their excessive accumulation in the brain.249 Kidney biopsy data from elderly individuals indicate that ageing is associated with a decline in the glomerular filtration rate.250 Moreover, the kidney is capable of secreting antiageing factors, such as klotho, which has been shown to enhance cognition and neural resilience. Furthermore, it has been observed that the level of kolotho decreases during the ageing process of the kidney.251,252 Additionally, the kidneys also release various proteins that promote brain ageing, such as kidney-associated antigen 1.253

To date, research on the pathogenic mechanisms of aged kidneys in neurodegenerative diseases has predominantly focused on AD and PD. The kidney serves as an organ that mediates the clearance of peripheral Aβ. Patients with CKD and animals undergoing unilateral nephrectomy exhibit elevated levels of circulating and cerebral Aβ, along with impaired cognition.254,255,256 In addition, renal insufficiency also leads to increased levels of circulating uraemic neurotoxins such as parathyroid hormone and neuropeptide Y, which adversely affect hippocampal neuronal apoptosis and the permeability of the BBB, respectively.257 Due to the activation of the renin-angiotensin system in aged kidneys, there is an increase in angiotensin II levels which acts on angiotensin II type 1 receptors in the substantia nigra and striatum. This induces oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby increasing the risk of PD.258,259

Lung–brain axis

The adequate delivery of oxygen to the brain heavily relies on pulmonary ventilation and gas exchange. However, lung function tends to deteriorate with age, which can be indicated by a reduction in the forced expiratory volume in one second to forced vital capacity ratio (FEV1/FVC).260 Furthermore, the phagocytic capacity of alveolar macrophages and neutrophils, which are responsible for pathogen clearance, diminishes in elderly individuals, thereby heightening their susceptibility to pulmonary infections.261 According to population surveys, poorer pulmonary function (PF) is associated with a decreased brain volume and increased white matter hyperintensity (WMH),262 and a 1-year increase in the lung BA increases the brain BA by 25 days.

Autopsy investigations revealed that decreased PF is associated with a greater burden of AD pathologies, including amyloid deposition and neurofibrillary tangles.263 The potential mechanisms may involve the induction of chronic hypoxia and subsequent activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1), which in turn accelerates the production of Aβ via the overexpression of β-secretase and γ-secretase while impairing Aβ clearance through microglial dysfunction.264 Moreover, chronic hypoxia is thought to trigger α-syn phosphorylation and aggregation, which interacts with hypoxia-induced mitochondrial dysfunction to worsen PD progression.265

Additionally, a large-scale epidemiological study demonstrated that infectious diseases, including pulmonary infections, increase the risk of AD and PD dementia (PDD).266,267 Additionally, a special type of pathogen, M. tuberculosis, which primarily targets the lung, increases the risk of PD by 1.38 times. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in several genes, namely, LRRK2, PARK2, and PINK1, confer susceptibility to both mycobacterial infection and PD.268 The most common virus associated with parkinsonism is influenza. Although these viruses do not directly affect the CNS, pandemic outbreaks of influenza are associated with encephalitis with Parkinsonian features. This finding is ascribed to each of these factors inducing a significant systemic infection characterized by the production of significantly high levels of cytokines and chemokines, namely, a cytokine storm, further initiating an inflammatory cascade in the brain.269

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has emerged as the most extensive and persistent global health crisis in recorded history. The neuroinvasive nature of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) allows it to invade the brain through both the olfactory route and the vagus nerve, which may be an important mechanism for causing clinical symptoms such as early olfactory loss, gastrointestinal and respiratory dysfunctions in COVID-19 patients.270,271 Autopsy evidences from COVID-19 patients directly demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 enters the CNS partly through the olfactory mucosal-nervous milieu. This is supported by high viral RNA levels in the olfactory mucosa, and the presence of SARS-CoV spike protein in olfactory neurons.271 Moreover, even when respiratory testing for SARS-CoV-2 yields negative results, viral RNA can still be detected in faeces, indicating persistence and replication of SARS-CoV-2 within the gastrointestinal tract.270 It has been hypothesized that retrograde invasion of CNS via the vagus nerve may occur with SARS-CoV-2.272 Furthermore, autopsy evidence from two cases reveals immunohistochemical detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the vagus nerve fibres located on the surface of the brainstem, suggesting potential transportation of virus from lungs to brain through this pathway.273,274

The elderly population demonstrates a elevated susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Epidemiological evidence indicates that individuals aged 80 and above have approximately three times higher incidence of COVID-19 compared to those aged 45 to 79, and significantly greater than individuals under the age of 24 during the initial phase of the American epidemic.275 Infection with SARS-CoV-2 triggers a cytokine storm, inflammation, cellular senescence, age-related immunosenescence, as well as diminished physiological reserves in the respiratory system and other organs.276,277 These processes are commonly associated with ageing and also implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 directly induces AD pathogenesis such as neuronal damage and amyloid processing,278,279,280 as well as PD pathogenesis including α-syn aggregation and dopaminergic neuronal loss in various models.281 Previous studies have demonstrated an association between COVID-19 and long-term brain atrophy and cognitive impairment in older individuals.282,283 The Real-time Assessment of Community Transmission (REACT) study conducted in England involving over 140,000 participants revealed that COVID-19 leads to persistent objective cognitive deficits lasting for one year or more after infection.284 Similarly, COVID-19 exacerbates both motor and nonmotor symptoms in PD patients, particularly urinary issues and fatigue.285,286 In conclusion, SARS-CoV-2 may accelerate the ageing process while increasing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases among older adults.

Muscle–brain axis

Muscles secrete numerous myokines that mediate bidirectional communication between the muscles and multiple organs. For example, cathepsin B and fibronectin type III domain containing protein 5 (FNDC5)/irisin have been shown to enter the brain and enhance neurogenesis and cognition.287 Irisin has also been revealed to increase telomerase activity to extend the lifespan.288 During ageing, the secretion of these myokines decreases.289 Additionally, a 1-year increase in the muscle BA increases the brain BA by 13 days. Therefore, a plausible speculation is that aged muscles have the potential to drive brain ageing.

Muscle ageing is a risk factor for the occurrence and development of several age-related diseases.290 Studies have shown that sarcopenia in elderly individuals is associated with a greater risk of AD and faster cognitive decline.291 However, the exact mechanisms underlying this relationship remain unclear. In light of previous studies, two potential explanations are proposed. First, the abundance of muscle-derived Aβ increases with age, potentially contributing to Aβ deposition in the brain.292 Second, decreased levels of myokines may account for the deterioration of cognitive function and neurodegeneration.289 In addition, neuromuscular junction dismantling and denervation occur in aged muscle, which are also key factors contributing to the onset of clinical symptoms and pathogenesis of ALS.293 In addition, a well-recognized observation in HD patients is defects in energy metabolism in skeletal muscle. mHTT affects mitochondrial complex activation and dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain in skeletal muscle, which may be markers of HD progression.294

Bone–brain axis

Bone releases cytokines such as osteocalcin (OCN) and lipocalin-2 (LCN2), as well as bone marrow-derived cells, which affect the brain. OCN promotes brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters to improve cognitive function. Conversely, LCN2 induces the activation of glial cells and neuroinflammation.295 During ageing, bone support is diminished due to decreased OCN levels, as well as increased LCN2 and sclerostin levels. Moreover, age-related brain atrophy and ventricular enlargement have been linked to osteoporosis, further emphasizing the impact of aged bone on brain ageing.296

Osteoporosis may accelerate atrophy of the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus, increasing the risk of AD by 1.27 times.297 Accordingly, in a study of a large number of postmenopausal women, osteoporosis increased the risk of PD by 1.4 times.298 Even if no obvious evidence for the relationship between osteoporosis and HD is available, bone mineral density is significantly lower in pre-HD carriers than in healthy controls.299 Additionally, osteoblasts have been reported to produce Aβ, this might be involved in the development of AD. Transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells upregulated beclin-1 expression, increasing autophagy in the hippocampus to clear Aβ.300 Furthermore, changes in bone-derived cytokines during ageing may also be implicated in several neurodegenerative diseases.301 For example, OCN decreases the Aβ load, increases glycolysis in microglia and astrocytes,302 and ameliorates motor deficits and dopaminergic neuronal loss in PD mice.303 LCN2 and sclerostin aggravate neuroinflammation and abolish synaptic plasticity,304,305 thereby accelerating the progression of AD, PD and ALS.306,307,308

Blood‒brain axis

The blood circulation connects the brain and each organ of the body, thus collecting pro-ageing and antiageing factors derived from various organs or systems. Systemic factors in the blood can directly cross the BBB or blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier, or indirectly transduce signals to target neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and other targets to regulate brain function.309 Exposing a young mouse to plasma from old mice impairs synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis and cognition,310,311 suggesting that aged blood contributes to brain ageing.

A variety of complex components of the circulatory system are associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Blood-derived Aβ has been found to enter the brain, inducing homoeostasis disorders and AD-related pathology.312 Platelets, which are responsible for approximately 90% of circulating Aβ,313 are overactivated with ageing314,315 and are reported to release more Aβ and subsequently induce Aβ deposition in the brain and cognitive impairment.316 Additionally, serum albumin, which is responsible for adhering to and transporting Aβ, is inversely associated with Aβ deposition in the brain.317 Serum albumin levels decrease with age,318 possibly increasing Aβ deposition in the brain, as albumin is able to sequester Aβ from the blood.319