Antibiotic ecotoxicity and resistance risks in resource-constrained chicken and pig farming environments

Introduction

Antibiotic usage in animal production systems and discharge of agricultural wastes into the environment is one of the main contributors to the global “silent pandemic” of antimicrobial resistance (AMR)1,2,3. While the overall AMR risks in developed regions are understood, evidence in resource-constrained regions has focused on animal and clinical/human health data. Recent strategies enumerated in National Action plans were informed by robust AMR data and hence will potentially offer better outcomes because of the One Health approach4. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), research and policy efforts have overlooked the environmental dimensions of AMR and there is a lack of urgency to evaluate it, resulting in systematic vulnerabilities5. Most farms in these regions are near human settlements and have been expanding and mechanizing rapidly, which promotes AMR in the animal-environment interphase and ultimately threatens human health6. Despite evidence of antibiotic misuse and overuse resulting in residual persistence in the environment, the effect on the animal-environment continuum remains unquantified7. The emerging environmental AMR presents a public health and ecological concern8.

Pig and chicken production is the fastest-growing livestock sector, and this trend will continue, especially in LMICs, in alignment with consumer preferences9. These sectors are associated with high antibiotic usage per kilogram of animal produced, with chickens and pigs consuming 148 and 172 mg/kg of respectively10. Between 5 and 90% of the antibiotics are excreted in urine and feces, which end up in the agricultural environment, selecting for AMR. Sustained discharge of antibiotics maintains bioavailable antibiotics and AMR agents in agricultural ecosystems, exacerbated by poor manure treatment and disposal strategies11.

Nearly half of Kenyan households (~5.5 million) keep poultry, with a total population of 43.8 million birds, while the pig population is smaller at ∼0.5 million pigs but is increasing12. The livestock sector is crucial for the economy, accounting for 12% of Kenyan agricultural GDP, and addressing nutrition insecurity13. Most AMR risk assessment studies in Kenya focus on veterinary antibiotic usage, single environmental matrix occurrence, and AMR at human-animal-environment interfaces6,14,15,16. However, there is limited data on AMR risks in the animal-environment-human pathway. Unlike the targeted effects of antibiotics administered for disease management, antibiotics discharged into the environment can affect multiple organisms and ecosystems. The environment is complex and characterized by interconnected relationships; hence, antibiotic contamination risks can impact several organisms and ecological processes17.

In this study, we analyzed the concentrations of eight commonly used veterinary antibiotics in the manure-soil pathways of semi-intensive chicken and pig farming systems in Kenya. Additionally, we conducted a risk assessment of antibiotic ecotoxicity, AMR selection, examining their association with farming practices to better understand the impact of antibiotic pollutants on AMR risks in a resource-constrained context.

Results

Study population demographics and farm management practices

In total, we collected 269 environmental samples: 97 fresh manures (52 from chickens and 45 from pigs), 92 from compost (47 from chickens and 45 from pigs), and 80 from soil (42 from chicken and 38 from pig farms). Water samples were collected from all farms (97), and feed samples from 62 farms (25 from pigs and 37 from chickens). The frequencies of the variables considered in the two farming systems are presented in Table 1. More men (51.5%) than women (48.5%) participated in this study, and most of the respondents had formal education (92.1%). The most frequent flock/herd size was 200–999 chickens (26.7%) and 80–109 pigs (22.2%). Antibiotic use for treatment is the primary purpose for administration (86%). Private veterinarians provide animal health services to 60% of pig farms and 57.7% of chicken farms, and 91.2% of the farmers can access veterinary services from providers with formal qualifications. Agrovets are the dominant antibiotic source in 76.9% of chicken farms and 66.7% of pig farms. Of all the chicken farms, 63.5% had used antibiotics over the past two months, and less than half of the pig farms (46.7%) had used antibiotics. Oxytetracycline and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim combination were prevalent antibiotics shared by both farming systems, whereas tylosin was notably high in pig systems (23.1%). Generally, chicken farms had higher numbers of used antibiotic packets than pig farms, but two used antibiotic packets were the mode in both farming systems. Manure management in pig farms was frequently done through heaping above ground (68.9%), while chicken farmers frequently used pit storage (55.8%).

Distribution of antibiotic residues

The mean antibiotic frequency across all samples was in the order of sulfamethoxazole > tylosin > tetracycline > oxytetracycline > trimethoprim > streptomycin > penicillin G > sulfadiazine (Table 2). In pig farms, manure-fertilized soils were the most frequently contaminated sample type with antibiotics (23.0%, n = 70/304), while in chicken farms, compost was most frequently contaminated with antibiotics (25.8%, n = 97/376). Pig manure-fertilized soils and chicken manure were positive for all the tested antibiotics. Sulfamethoxazole was the most common antibiotic detected in environmental samples (39.2%). Feeds had 5.2% antibiotics detection, and no antibiotics were detected in the drinking water.

Despite antibiotics being detected, the average antibiotic concentrations were low, with only the following samples exceeding 100 µg/kg: tetracycline (chicken manure-fertilized soil), trimethoprim (manure-fertilized soils in both systems and pig manure), sulfadiazine (manure-fertilized soils in both systems), sulfamethoxazole in chicken manure and compost. For the cumulative averages, only trimethoprim across all samples and pig manure-fertilized soils across all antibiotics exceeded the threshold. Compost had the lowest cumulative concentration in both systems (Table 3).

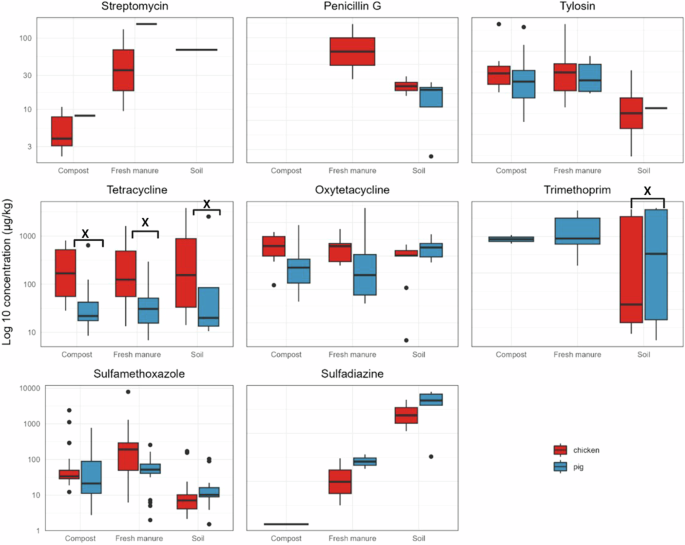

Chicken farms had higher levels of tetracycline and oxytetracycline than pig farms (Fig. 1). Although trimethoprim was infrequently detected, the concentrations were high, explaining the inflated means (Table 3). Only tetracycline and trimethoprim concentrations in manure-fertilized soils differ significantly between pig and chicken farm systems (Kruskal–Wallis test; p < 0.05). The compost had low antibiotic concentration with no quantification of Penicillin G in both systems and no sulfadiazine in the pig system. Trimethoprim had a high concentration in soil with wide distribution in both systems but low levels in compost and manure.

Relative concentration distribution of streptomycin, Penicillin G, tylosin, tetracycline, oxytetracycline, trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole and sulfadiazine concentrations in compost, fresh manure, and soil organized by chicken and pig farm system. The horizontal lines inside the box represent the median concentration, upper and lower edges represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers extending from the bottom and top sides of the box represent the lowest and the highest quantified concentrations and [X] above the box plots show significant differences between chicken and pig systems.

Risk assessment of the environmental impact attributable to levels of antibiotic residues

The likelihood of ecotoxicity risks to the soil organisms and the likelihood of AMR selection due to the presence of antibiotic residues was analyzed. Antibiotic concentrations exceeding the ecotoxic threshold were few (11.8%, n = 115/1944), and there was no statistical difference between chicken and pig farm systems. The risks of antibiotic contamination were spatially distributed across the study sites (Supplementary Fig. 1).

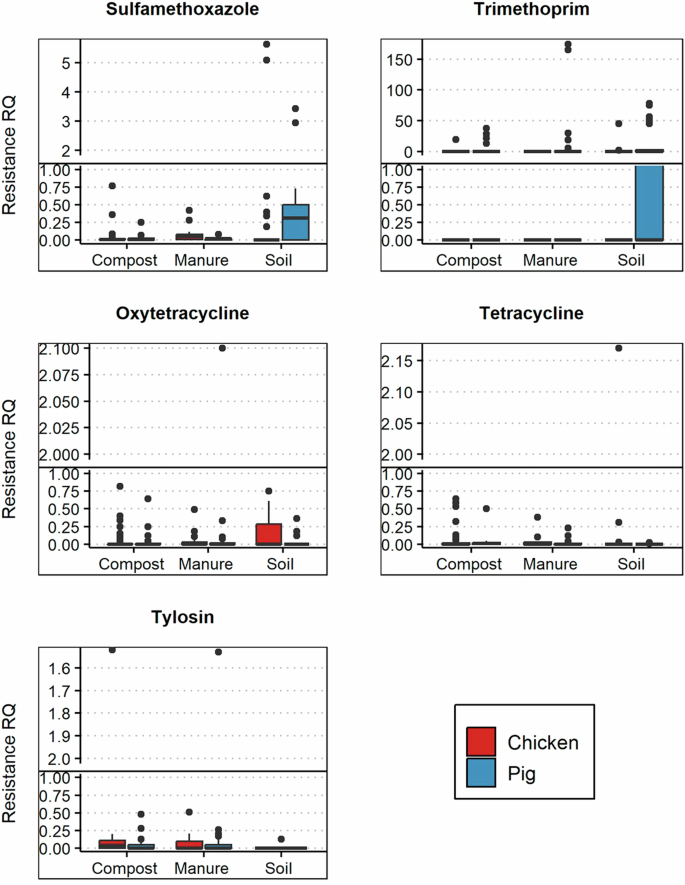

Our models indicate that the likelihood of ecotoxicity risks to the soil organisms at the antibiotic residue concentrations was negligible except for a few outliers (Fig. 2). Compost and manure exerted low to medium risks (RQ < 1) to plant roots but low risks (RQ < 0.1) in manure-fertilized soils. The risk per test organism showed no significant difference across the different environmental matrices (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.06).

The h-line denotes RQs above 1, representing high risk.

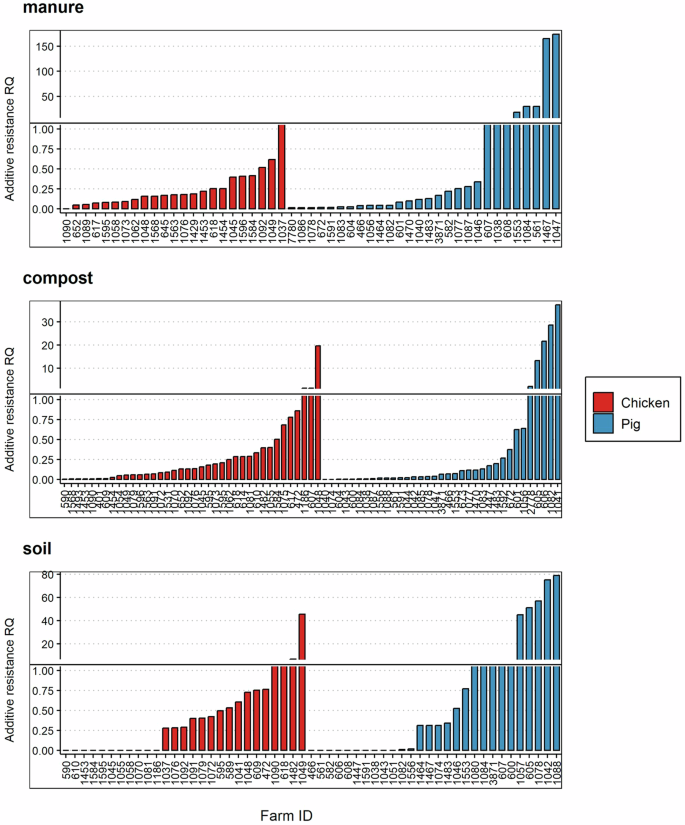

The additive ecotoxicity risks were low (RQ < 0.1), and most farms were exposed to medium ecotoxicity risks (RQ < 1) attributable to individual antibiotic concentration. Soil organisms had the lowest risk, with only two chicken manure-fertilized soils and five pig manure-fertilized soils presenting a high risk (RQ > 1) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Although manure and compost had a comparatively higher proportion of farms with RQ > 1, the differences between matrices and across farms were not statistically significantly different (t test, p = 0.05).

The results are derived from cumulative RQs of the test organism’s endpoints (earthworm, plant, gram-positive bacteria, and gram-negative bacteria) against the antibiotic (trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, oxytetracycline, and tylosin) concentration per farm. The h-line denotes RQs above 1, representing high risk.

The additive AMR selection risks in pig farm systems were higher than in chicken farm systems (Table 4). Similarly, matrix-specific maximum AMR selection RQs were higher in pig farms. For example, maximum RQs in chicken farms ranged from 1.3 (manure) to 45.6 (soil), whereas in pig farms, ranges were from 37.3 (compost) to 174.4 (manure). All antibiotics had low to medium (RQ < 1) AMR selection risk except for a few outliers (Fig. 4). Only sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim exert high risks (RQ > 1) in pig manure-fertilized soil; however, the average risk was medium (RQ < 1).

Distribution of resistance risk quotients of sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, oxytetracycline, tetracycline, and tylosin across environmental samples and production systems. “•” are outlier risk quotients. The h-line denotes RQs above 1, representing high risk.

The resistance RQs were lowest in compost but the highest in manure-fertilized soils (Supplementary Fig. 3). Pig compost had the highest frequency of outlier RQs, suggesting high resistance selection risks in specific farms. Resistance RQs differences across the matrices were not statistically significant (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.11). However, the additive AMR risks in pig farm systems were significantly higher than in chicken farm systems (t test, p = 0.01).

Chicken farm systems had few high AMR selection risks (RQ > 1), with pig manure-fertilized soils recording the highest cases (Fig. 5). Even though there was no significant difference in risk between matrices within a farm system (p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA), the mean likelihood for AMR selection in pig farm systems was significantly higher (t test, p < 0.05).

The results are derived from cumulative RQs of all antibiotics quantified in a farm system. The h-line denotes RQs above 1, representing high risk.

Association of farm practices with additive ecotoxicity and AMR selection risks

The univariable analysis revealed a significant association between AMR selection risks and several farm practices, including herd/flock size, used antibiotic packages on the farm, and manure management/storage. The multivariable analysis indicated that rearing between 4000–4999 chickens (est = 0.73 CI [0.11–1.35], p = 0.02), and ≥5000 chickens (est = 1.01, CI [0.53–1.49], p = 0.001) was significantly associated with increased antibiotic ecotoxicity (Supplementary Table 1). While in pig farming systems, increased ecotoxicity risks were associated with regular application of manure in croplands (est = 2.08, CI [1.07–3.09], p = 0.001), rearing pig herd size of 110–139 (est = 2.20, CI [0.76–3.64], p = 0.003) and pig herd size >200 (est = 3.84, CI [1.85–5.83], p = 0.001) (Supplementary Table 2). There was no significant association between the farm practices and AMR selection risks in chicken and pig farming systems (p = 0.09, generalized linear model (GLM)).

Discussion

Environmental AMR and antibiotic residues have severe ecological and public health implications; hence, understanding their levels and potential risks is vital for pollution control and improving antimicrobial stewardship. Our results reveal negligible levels of antibiotic residues in animal feeds and drinking water, sporadic antibiotic contamination in different environmental samples, and low but reasonable ecotoxicity and AMR selection risks in the environment.

Only one study has previously reported on antibiotics in Kenyan soils18. To the best of our knowledge, there has yet to be survey data on AMU and farm management practices, including manure management in manure-soil pathways coupled with quantification of antibiotic residues in the same agroecosystem. We characterized the presence and concentrations of eight commonly used veterinary antibiotics in chicken and pig production inputs (i.e., feeds and animal drinking water) and environmental discharges (i.e., manure, compost, and manure-fertilized soils). Furthermore, we used LC-MS/MS, the primary analytical technique for antibiotic residue analysis, because it expands beyond traditional screening methods such as immuno-assays, which have relatively higher LODs; hence, low-concentration antibiotics will be missed19. Our results showed that different antibiotics exert varying pollution pressure at various points along the manure-soil pathway, and a deterministic risk assessment of the five dominant antibiotics was also applied to evaluate ecotoxicity and AMR selection risks.

Seventeen percent of samples were positive for antibiotics, with sulfamethoxazole and oxytetracycline being the most frequently detected. Although the number of antibiotic-positive samples between the two farming systems was not statistically different, samples from the pig farming systems were more positive. A previous study on antibiotics in Kenyan agricultural soils reported the detection of antibiotic residues in >50% of samples; however, it did not indicate the type of fertilizer or manure used in those farms18. Similar studies in high-income countries are based on analyzing single-type matrices. For example, 96% of pig slurry in southeastern Europe, and 27–29% of livestock manure in Belgium contained antibiotic residues16,20. These studies used varying sampling and analytical techniques, focusing on a single environmental matrix. Therefore, making comparisons of risks is challenging. Our study utilizes a comparable sample analysis method and traces the antibiotic pathways in a connected production system coupled with a deterministic risk assessment.

Chicken compost and pig manure-fertilized soils were most frequently contaminated with antibiotic residues. In most farms, chicken compost management was not optimal to enhance antibiotic residue degradation. Chicken compost is sometimes stored temporarily before reuse, e.g., feed to cattle or applied in agricultural soils as fertilizer. Conventional management of chicken compost only partially reduces antibiotic contamination and, in some cases, demonstrates non-significant degradation15,21. Based on the observed chicken compost management approaches in the study, removing litter after a production cycle and applying it on croplands can lead to antibiotic accumulation because of limited exposure to environmental elements, e.g., heat, which could enhance antibiotic degradation. Pig manure-fertilized soils receive slurry and pig manure continuously from cleaning and slurry discharge, acting as recipients of antibiotic residues from treated animals. However, it is worth noting that in our study, we could only detect antibiotic residues in 18.3% of fresh manure, which could be attributed to low antibiotic usage, which was confirmed by the farmers during the survey and further supported by the-significant association between antibiotic usage within the past two months and AMR selection risks. Moreover, we did not detect most antibiotics in the feeds and animal drinking water.

In the positive samples for antibiotic residues, manure-fertilized soils had higher antibiotic concentrations than compost and fresh manure. Although the dilution effect along the animal-soil pathway is expected to lower the antibiotic concentrations, we can assume that farms have continuously used antibiotics containing manure to fertilize crop fields. Trimethoprim was found in the highest concentration compared to other antibiotics tested, above the ecotoxic threshold of 100 µg/kg, with a mean of (221.4 µg/kg) and maximum concentration in pig-fertilized soils (696.2 µg/kg), but low concentrations in matrices associated with chickens. Sulfamethoxazole was the second highest (87.1 µg/kg) but below the ecotoxic threshold. This high detection frequency and concentration of sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim agree with studies in Ghana, Poland, and China22,23,24. Trimethoprim is often co-formulated with sulfonamides and has been widely used for treating various infections. Nonetheless, low trimethoprim detection may be because of short half-lives in the environment25. Although the survey showed high antibiotic usage within the past two months at 63.5% (chicken) and 46.5% (pigs), the antibiotic leftovers on the farm were low (Table 1). Tylosin had the highest number of leftovers (12 packets), followed by the sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim combination (8 packets).

Samples associated with chicken farming systems were more likely to be positive for tetracyclines. Laboratory analysis showed that they had higher tetracyclines concentration than those samples from pig farms, which was confirmed by the more frequent use of oxytetracycline in poultry compared to pig production, as shown in Table 1. Similarly, chicken manure-fertilized soils had high tetracyclines concentrations that could be attributed to residual contamination followed by prolonged usage and persistence for >100 days22. The observed average concentration of tetracyclines (54.4 µg/kg) was fourfold higher than those reported in Kenya (10 µg/kg) by Yang et al., but relatively lower than the concentrations detected in Tanzania: 1573.75 µg/kg (poultry) and 1473.61 µg/kg (pigs)18,26. However, this study reported lower concentrations than studies in Southeastern Europe, Spain, and China16,23,24. Generally, high temperatures, and humidity in the tropics might accelerate the degradation of tetracyclines in the environment, which may explain lower concentrations27. This study expected higher tylosin detection and concentration because of the numerous empty packages observed during our farm visits (unreported). However, no studies within our region have reported tylosin residue analyses, and in other regions, the reported concentrations were below the LOQ, which may be attributed to the short half-lives28,29. Kolz et al. observed a 60–85% degradation rate of tylosin in swine manure under anaerobic conditions within 24 h and near complete degradation within 12 h under aerobic conditions30. It is unclear the degradation rate under the real-life conditions in the tropics, therefore there is a need for further mesocosm experiments to determine the fate of tylosin.

Based on the concentrations of antibiotics, the lowest ecotoxicity risk was to earthworms, suggesting a low perturbation of soil ecological processes. Earthworms are responsible for modifying soil properties such as water infiltration, nutrient cycling, soil structure maintenance, and soil functioning31,32,33,34. However, the likelihood of risk to bacterial populations was higher than on earthworms, with an even higher risk to Gram-negative bacteria than Gram-positive. Although, the average risk was low (RQ < 0.1), the effects may disrupt the soil microbiome affecting microbial diversity and function or ecological system services35,36. The rhizosphere microbiome plays a vital role in plant nutrition, growth, and health, supporting beneficial services such as enhanced nutrient uptake, improved root architecture, and protection against plant pathogens37. Such soils can result in lower crop yields, antibiotics accumulation in crops and pose a health risk to consumers38,39,40. Therefore, manure composting and manure-fertilization ratios are critical soil health management approaches under the current scenario.

The AMR selection risk assessment reveals that the highest RQs were in manure-fertilized soils. Although a few antibiotics presented high risks (RQ > 1), the mean RQs were low, suggesting negligible AMR resistance selection risk41. The additive risks in manure-fertilized soils in both systems were high. Trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole contribute a significant resistance selection risk weight, especially in pig manure-fertilized soils. In agreement with Rasschaert et al. and Dawangpa et al., there is a correlation between trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole detection with AMR resistance selection risks in manure-soil systems42,43. In chicken farm systems, oxytetracycline resistance selection risks were more pronounced, especially in manure-fertilized soils. Similar observations of oxytetracycline resistance risks in poultry systems have been reported44,45.

These findings show that ecotoxicity risks were associated with antibiotic concentrations in larger flock/herd sizes, suggesting that high animal populations use more antibiotics and seek veterinary services resulting in more antibiotic excretion. We posit that farms with large herd/flock sizes use more antibiotics and, hence, higher levels of antibiotic residues in manure, highlighting the importance of manure storage and management practices. We hypothesize that pollution risks associated with antibiotic residue contamination identified may be attributed to long-term AMU, environmental persistence of residues, and inappropriate manure management methods, making the farm environment a reservoir of antibiotics and AMR. Moreover, our results suggest that the type of manure is associated with the degree of ecotoxicity and AMR selection risks in Kenyan agroecosystems; hence, manure storage and waste management processes should be designed depending on the source.

AMR risk assessment in the farm environment must take into consideration monitoring of antibiotic residue levels in different environmental samples and include ecological safety assessments. Additionally, antibiotic residues and AMR levels in manure and manure treatment methods that reduce AMR risks and reuse scenarios should be clarified to inform policy and technical interventions. Future studies should include a larger sample size collected longitudinally and across production cycles coupled with a higher number and diversity of test organisms. Moreover, our results-focused only on eight commonly used antibiotics, but risks associated with other antibiotic classes and other antibiotics within the same class may produce a different outcome. Recent studies have demonstrated the high use of other antibiotics of critical importance, e.g., fluoroquinolones, colistin, and cephalosporins7,14,18. Lastly, future studies can leverage the results from this study and broaden the objectives by coupling ecotoxicity assays with AMR gene identification, and quantification.

This cross-sectional survey characterized the occurrence and concentration of antibiotic residues and assessed the AMR selection risks in Kenyan semi-intensive chicken and pig production systems. Our findings indicate that farm practices and manure management are associated with the fate of antibiotics in manure-soil pathways. The dominant antibiotics were sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim in pig systems and oxytetracycline in chicken systems. Although the ecotoxicity and AMR selection risks were low (RQ < 0.1), they were reasonable and should not be ignored. As livestock production intensifies, AMU and AMR are likely to increase and, hence, have a greater chance of environmental pollution, thus requiring frequent environmental monitoring and surveillance coupled with non-intrusive risk assessment approaches for early detection of environmental AMR risks in resource-constrained contexts. This study provides crucial insights for understanding the environmental health impacts of antibiotics in Kenyan agroecosystems, which can be used to guide pollution control decision-making and increase awareness of environmental AMR risks.

Methods

Study area

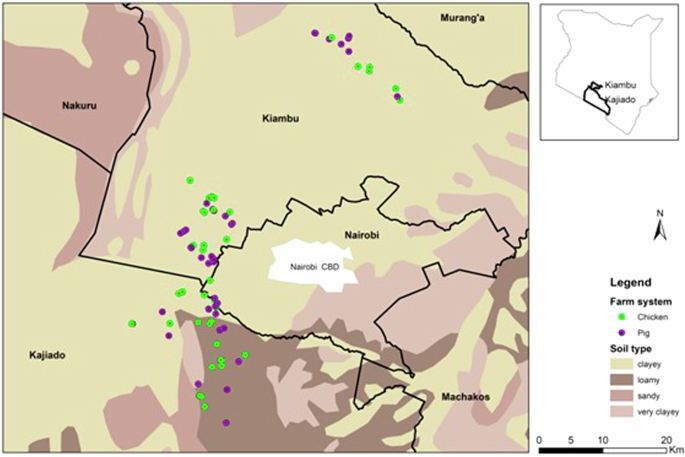

The study was conducted in two neighboring counties, Kajiado and Kiambu, which are adjacent to Nairobi, the capital of Kenya (Fig. 6). These counties are highly cosmopolitan, supplying agricultural products to urban centers and Nairobi city. Backyard chicken and pig farms in three sub-counties within each county were selected for this cross-sectional study between April and July 2022. The duration corresponds to the soil preparation and crop farming periods in the study area. Farm data from the government veterinary repository was used to identify 97 farms (45 pigs and 52 chickens). The choice of sub-counties and farms was guided by the assumption that farmers with high productivity would have similar farm practices. The farm selection was actualized by using a purposive sampling approach. According to the Farm Overall, the dominant soil texture in both areas is clayey, with small fractions of loamy in Kajiado. The soils in Kiambu are Nitosols, and Kajiado is Ferrosols46.

Farm distribution in the selected sub-counties in Kiambu and Kajiado, Kenya. The soil type is also indicated.

Collection of survey data

Before inclusion in the study, farmers signed a written informed consent detailing the purpose of the research and requesting voluntary participation. Thereafter, they completed a validated survey questionnaire that collected information on farm demographics, antimicrobial use, and manure management and manure usage (Supplementary Survey Tool 1). The researcher and trained veterinarians administered the questionnaires. Data from the questionnaires were recorded using Open Data Kit Collect software on electronic tablets and uploaded to secure databases at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

Sample collection

Subject to availability during sampling, 1 L of drinking water, 20 g of feed, manure, compost, and soil were collected on each farm. Fresh manure was collected from all the animal-holding areas, compost from three representative points in a manure heap, and the manure-fertilized soils from the corresponding croplands receiving manure. The manure-fertilized croplands were within 500 m of the animal-holding area and did not receive reclaimed water irrigation or manure from other sources. The soil samples were collected using cores at 0–30 cm depth in a zigzag pattern from representative points across the farm and pooled to achieve a representative sample. Sampling depth was informed by previous data showing that antibiotic concentrations at levels deeper than 30 cm are <20% of the surface level values47. Feeds and water samples were composited from all feed troughs and drinkers on a farm. Samples from the same matrix were mixed to form one composite sample on each farm. All the samples were collected in composited triplicates, transferred into zip-lock bags, and transported on ice to the laboratory at ILRI, Nairobi, within 4 hours. The samples were stored in the laboratory freezer at −20 °C until analysis.

Residues chemical analysis

Eight commonly used veterinary antibiotics representing six antibiotic classes were analyzed per sample across the matrices totaling 2152 analysis units. They included tetracyclines (tetracycline and oxytetracycline), sulfonamides (sulfamethoxazole and sulfadiazine), macrolides (tylosin), aminoglycoside (streptomycin), beta-lactam (penicillin G) and diaminopyrimidines (trimethoprim). Their structure, Chemical Abstract Service number, and chemical and physical properties are shown in the Supplementary Table 3. All the analytes were HPLC pure grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemmie Gmbh (Steinheim, Germany).

Chemicals and standards

All the chemicals and standards were ACS reagent grade. Methanol (MeOH) and acetonitrile (MeCN) of ≥99% purity were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) and Ammonium Acetate, Citric Acid, Sodium Phosphate Dibasic, Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), anhydrous Na2SO4, Supel CleanTM PSA SPE bulk packing DSC-18 SPE bulk packing, and Formic Acid (FA) of ≥99% purity was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim am Albuch, Germany). The antibiotic analytes were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim am Albuch, Germany). Water (H2O) was HPLC grade (generated by a Milli-Q Gradient purification system, Millipore, Brussels, Belgium). PTFE filter membranes (0.22 µm × 25 mm) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim am Albuch, Germany). Individual stock solutions were prepared for each analyte, mixed analyte, corrected for stock purity, and stored in dark conditions at −20°C. Stock standards were prepared in acetonitrile for each analyte. Working standards and solutions were prepared freshly before each experiment

Sample extraction and LC-MS analysis

Antibiotic extraction from manure, compost, soil, water, and feeds was performed using methods validated by Van den Meersche et al. and Rashid with minor modifications48,49. Manure, compost, soil, and feed were freeze-dried for 48 h, then ground into fine particles using a sterilized pestle and mortar. Two grams were weighed into 50 mL falcon tubes, hydrated with 2.5 mL of 0.1 M NaEDTA McIlvaine buffer (pH 4.0), followed by vortex mixing (1 min) and sonication (30 min) for sample disintegration. 8 mL solution (ACN and 6% TCA) was added to compost and manure, and 10 mL solution (MeOH & EDTA-McIlvaine buffer, 1:1 v/v) was added to soil and feed samples followed by shaking in a horizontal shaker at 2500 RPM for 15 min then centrifuged at 20,000 RPM for 20 min. One mL of the supernatant was transferred to an Eppendorf tube and topped up with 1 mL of ACN, then vortex mixed for 1 min followed by centrifuging for 15 min at 10,000 RPM. A clarifying agent (900 mg anhydrous Na2SO4, 50 mg PSA, and 150 mg C18) was added to the ACN phase, followed by centrifuging at 10,000 RPM for 3 min and extracted for filtration.

Water samples were centrifuged at 4700 rpm for 25 min at 4°C then spiked with 30 µl 25% NH4OH. The sample then underwent an SPE clean-up using Oasis HLB 200 mg 6 cc extraction cartridges (Waters, Ireland) after pre-conditioning. The extracted samples were eluted using 5 mL of MeOH with 5% (v/v) FA followed by 5 mL ethyl acetate. The eluents were evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen and then reconstituted with 200 µL acetonitrile. Finally, the extracts were filtered (0.22 µm PTFE filter membrane) into amber vials ready for injection into LC-MS/MS.

Method validation and quality assurance

The method was validated according to the guidelines of the European Commission Decision 2002/657/EC50. The quality control tests assessed included extraction recovery rates, precision, specificity, limits of detection (LOD), limits of quantification (LOQ), relative standard deviations (RSDs), and linearity (Supplementary Table 4). The standards were injected five times to evaluate their reproducibility—RSD of the signal. During sample analysis, the calibration standards were injected at the beginning and end of each sequence and repeated after every 25–30 injection to evaluate the signal stability. Matrix-matched calibrations were used to assess recoveries, and the results were within the internationally acceptable range of 70–120%50,51.

LC-MS/MS analysis

Identification and quantification of the antibiotics were performed using the Shimadzu Nexera Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry system LC-MS 8050 (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The system consisted of a SIL-30AC auto-sampler, LC-20AD solvent delivery pump, column oven, and the 8050 triple quadrupole detectors. Separation was performed at 40 °C using a Synergi Hydro-RP analytical column (2.5 µm particle size, 100 mm × 3.00 mm) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) operating at a 0.4 mL/min flow rate. The binary mobile phase consisted of phase A (water/formic acid, 99:1, v/v) and 10 mM C2H7NO2, and phase B (MeOH/ CH2O2, 99:1, v/v) and 10 mM formic acid was used (Supplementary Table 5).

Detection by MS/MS was performed on the Shimadzu 8050 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, fitted with an electrospray ionization source operating in positive ionization mode. The ionization source was under the following conditions: the nebulizing gas flow of 3.0 L/min, drying gas flow rates of 10.0 L/min, interface voltage of 4.5 kV; desolvation line temperature of 300 °C; heating block temperature of 400 °C, and CID gas flow 270 KPA. Direct infusion of neat individual standards into the MS/MS was performed to identify the veterinary standard transitions in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) modes for quantitation. Optimized MRM parameters for the antibiotic are shown in Supplementary Table 6. Instrumental data was extracted using LabSolutions version 5.89 (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan, 2014).

Environmental impact assessment

The predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC) values protect ecological species and incorporate assessment factors consistent with environmental risk methodologies52. The resulting ecotoxicity and AMR selection risk are ranked according to the risk quotient (RQ) criterion reported by Verlicchi et al., Hanna et al., proposing that RQ ≥ 1: high risk, 0.1 ≤ RQ < 1: medium risk and RQ < 0.1: low risk53,54,55.

Ecotoxicity risk assessment

Ecotoxicity refers to the potential of chemicals, such as antibiotics, to stress organisms by disrupting natural physiology, biochemistry, behavior, and interactions of species in the ecosystem56,57. We assessed ecotoxicity risks to indicator organisms: terrestrial invertebrates (earthworms), plants (cucumber), Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Bacillus amyloliquefaciens), and Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas putida) were used to determine chronic toxicity effects (Supplementary Table 7). The equilibrium partitioning method (Eq. 1) was adopted to estimate pore water PNEC as a terrestrial equivalent58. Decision on environmental impact was based on the European Union Environmental Medicines Agency’s guidelines on risks of medicinal products, which shows that concentrations ≥100 µg/kg exert plausible ecological impacts59.

Where Kd is the soil-water partition coefficient (Supplementary Table 8), the PNECwater was derived from studies based on the European Union Technical Guidance Document on risk assessment and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) data. The RQ of each antibiotic was calculated as shown in Eq. 2.

MEC is the measured environmental concentration in a matrix, and PNEC is the predicted no-effect concentration.

AMR selection risk

Common bacteria in the environment (e.g., Pseudomonas spp., Acinetobacter spp., Clostridium spp.) and manure (e.g., Escherichia spp., Streptococci spp., Salmonella spp.) were used to assess the risk of AMR selection (Supplementary Table 8). The AMR selection risks (RQresistance) were determined as the ratio of MEC to PNECresistance based on the values proposed by Bengtsson-Palme and Larsson41. The RQresistance was calculated using Eq. 3.

PNECresistance in terrestrial ecosystems was calculated from PNECwater based on the soil-water partition coefficient described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R Version 4.3.0 and mapping in QGIS software 3.16. Descriptive statistics were presented by matrix and farm system, then presented as percentages, means, and standard deviations. The differences between antibiotic detection across production systems were tested using Kruskal–Wallis test. Further, the mean concentration and risk differences across matrices were determined using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison tests (post hoc) test to identify specific differences. A T test was used to compare concentration and risk differences between the production systems. The farm practices and characteristics (the flock/herd size, AMU, veterinary services, and manure management) were subjected to univariate analysis using one-way ANOVA against ecotoxicity or AMR selection RQs. Farm practices and characteristics with p value (p < 0.2) were included in a multivariable generalized linear model (GLM) to identify significant (p < 0.05) associations with ecotoxicity or AMR selection RQs.

Ethical approval

The collection of metadata and environmental samples adhered to the legal requirements stipulated by the ILRI. Ethical approvals for pig and poultry manure sample collection were obtained from the ILRI institutional Research Ethics Committee (ILRI IREC) reference number ILRI-IREC2022-01. ILRI IREC is registered and credited to review research ethics by the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI) in Kenya. Farm sample collection, antimicrobial usage, and manure management survey were conducted under the approval of NACOSTI license NACOSTI/P/22/17603.

Responses