Anticipated variability increases generalization of predictive learning

Introduction

Imagine a virologist who discovers a new pathogenic virus with seven spikes. Later, the virologist observes a new group of similar viruses, but those ones have various sub-types, with two, five, eight or ten spikes. Would the virologist expect some of those viruses to also be pathogenic? Would they expect more sub-types of the newly discovered virus to be pathogenic if they had a reason to believe that there should be much difference in the number of spikes between the initial set of pathogenic viruses and the new set (e.g., if the environment of the original set differed from that of the new set?) If the virologist believed that pathogenic viruses within the new group should be very different from each other in their number of spikes? This example illustrates our research question: Would people generalize initial experiences more broadly when they expect more variability between the learning set and the generalization set as well as within the generalization set?

When people learn, they apply what they have learned not only to the specific stimulus they experienced, but also to novel, similar stimuli. In other words, they generalize1,2,3,4. Generalization is what makes learning useful, simply because new stimuli are never exactly the same as the learned ones. A crucial question is therefore what determines the breadth of generalization, or the strength of a learner’s expectation for objects that are similar yet not identical to the learned object.

A classic finding in learning is the variability effect (also known as the diversity effect): broader generalization occurs when people learn from a diverse (vs. non-diverse) set of objects5,6,7,8,9,10,11. For example, when people learned that diverse exemplars (i.e., watermelon, strawberries, and pineapple) predicted an outcome, they generalized this prediction to novel exemplars from that category (predicted the outcome with more certainty for orange, pear, and lemon), relative to people who learned a single type of exemplar (i.e., watermelon) that was presented three times at learning12. Note that in both cases there is an equal number of learning trials, and the difference lies only in the homogeneity (vs. variability) of the exemplars in the learning set (see11 for other types of the variability effect).

The variability effect has been explained by suggesting that variability affords abstraction13,14,15 (for a review see ref. 11). For instance, learning from a single exemplar (e.g., a watermelon) that is presented a number of times makes it difficult to identify the critical feature that predicts the outcome (e.g., is the effect predicted by its large size, its green color or the type of its seeds). But learning from diverse exemplars (e.g., watermelon, strawberries, and pineapple) makes it easier to identify the critical feature – it is the feature that remains stable across exemplars (e.g., they are all fruits). In that way, learning from diverse exemplars allows broader generalization that is based on abstracting a more general category16,17.

Importantly, the variability effect refers to actual variability within the learning set: learners generalize more when learning from a varied set of stimuli rather than a relatively homogeneous set. In this paper, however, we consider a different aspect of the relation between variability and generalization. Specifically, we ask how generalization is affected by expected variability, both between the learning set and the generalization set, and within the generalization set. To the best of our knowledge, this question has never been examined. Expected variability between the learning and generalization sets refers to the extent to which the (anticipated) generalization stimuli differ from the learning stimuli. To use our opening example, this refers to the difference between the learned pathogenic viruses (which all had seven spikes) and the viruses of the same type that one expects to see in the future. Expected variability within the generalization set refers to the extent to which the generalization stimuli are expected to be different from each other. That is, the extent to which the viruses of the same type that one will see in the future are expected to be different from each other (e.g., are they expected to have 2–10 spikes or rather 6–8 spikes). In this paper we focus on these two types of expected variability. We predict that learning in one context while expecting to apply the knowledge in a different context that is characterized by high (vs. low) variability would result in broader generalization.

We derive this prediction from the notion that breadth of generalization is determined by a trade-off between accuracy and applicability18, and that expected variability should shift the point at which this trade-off optimizes toward broader generalization. Narrower generalization is more likely to be accurate (if a novel stimulus is more similar to the learned object, then it is more likely to generate the same outcome as the learned object), but it can be potentially applied to fewer new objects (i.e., as the criterion of similarity to the learned object becomes more stringent, fewer new objects would be defined as similar). For example, generalizing from a virus with seven spikes to other viruses with seven spikes is more likely to be accurate than generalizing to all viruses with four-to-ten spikes, but obviously, it can be applied to fewer cases. Conversely, broader generalization obviously applies to more cases but is less likely to be accurate. When generalizing, a learner attempts to find a “sweet spot” between these two opposing considerations.

We propose that expected variability within the generalization set as well as between the learning set and the generalization set affects the point at which the accuracy-applicability trade-off optimizes. Specifically, when one expects an application context in which there are relatively few objects that are similar to the learned one, and relatively many objects that are different from the learned one, then a broader generalization is needed to ensure that learning would apply to enough objects. To use our opening example, if viruses are likely to vary in number of spikes between the learning contexts and the application context as well as within the application context, then narrow generalization might prove irrelevant for this future context. This is because there will be relatively few viruses with exactly seven spikes. In such a situation, one needs to “cast a wider net,” that is, generalize learning to a broader category of objects.

When should one expect variability in the application context? In some real-world situations, the change in the application context is known and expected. For example, when learning to shoot basketball, the learner expects to shoot from different places on the field. Similarly, when learning to read, children must be able to generalize letter-forms across fonts and sizes. Beyond such explicit knowledge, we suggest that psychological distance serves as a cue for potential variability and will therefore broaden generalization. This hypothesis is based on Construal Level Theory (CLT)19,20,21 which suggests that psychological distance, variability, and abstraction are interrelated.

Construal Level Theory (CLT) suggests that distancing an object or an event in any of the four dimensions of psychological distance (time, space, social distance, hypotheticality) affects the way we think about it. A relevant core insight of that theory is that distance introduces variability: More distal objects are increasingly less similar to our current experience and are increasingly uncertain and therefore potentially different from each other16,22,23. For example, what you will eat tonight is relatively known and predictable. But what you will eat for dinner 10 years from now includes many more possibilities, some of them unknown. As a result, people represent distal objects more abstractly, to capture this potential variability. For example, we are more likely to use “fruit”, rather than “watermelon” to describe what we will eat 10 years from now as opposed to what we will eat tonight. According to CLT, abstraction introduces stability and allows one to overcome the variability and unknowability of distant objects and events. An abstract representation of an object glosses over the variation and retains only features that are likely to remain stable across time, space, social perspectives, and hypothetical worlds.

We already mentioned that the variability effect could reflect greater abstraction when one learns from more diverse sets. We propose here that merely expecting variability in the application context could also afford greater abstraction and increase the breadth of generalization. This could happen both when there is explicit knowledge about high variability and when a more subtle expectation of increased variability is elicited by increased psychological distance to the anticipated application of one’s learning.

Our hypothesis aligns with various models of generalization in learning, in which breadth of generalization is at least partly determined by processes that occur already at learning. Bayesian models of generalization, for example, assume that learners update their beliefs about the likelihood of different probability distributions of the experienced stimuli based on exposure to specific and limited examples24. Learners may try to build an abstract structure of a domain and use it as a generative model to generalize to novel situations25,26. Similarly, according to the function learning account of generalization, learners generate rules that enable them to interpolate and extrapolate from training examples to novel cases. For instance, Busemeyer et al.27 proposed the Associative-Learning Model (ALM), a connectionist model in which inputs activate an array of hidden units, each representing a possible, yet not experienced, input value. The activation of each hidden unit depends on its similarity to the current input, allowing the learner to generalize a function from training examples.

In the Supplementary Materials, we propose a formal model and a simulation that build on these extant models. Our model suggests a possible mechanism for how generalization may be affected by expected variability in the learning set and expected variability between the learning and generalization sets.

To examine the prediction that expecting high (vs. low) variability would broaden generalization we conducted three experiments. In Experiment 1 and 3, we used a classic predictive learning task, in which participants predict whether an outcome would follow rings of different sizes. In the learning phase, participants learn about two rings of different sizes, only one of which is followed by an outcome (Fig. 1a). In the generalization phase, participants predicted whether the outcome would follow both the learned rings and rings of other size, of different similarity to the learned rings (i.e., generalization rings; see Fig. 1a). Experiment 1 manipulated expected variability by directly instructing participants to expect high versus low stimuli variability in the application context. Experiment 2 examined how anticipated variability is affected by increasing the temporal distance between learning and the anticipated application of this learning. Specifically, participants indicated their expectations regarding the variability of stimuli in the application set when temporal distance between learning and application was short versus long. Experiment 3 then replicated Experiment 1, but instead of direct instructions to anticipate more variability, it manipulated anticipated temporal distance between learning and application of that learning.

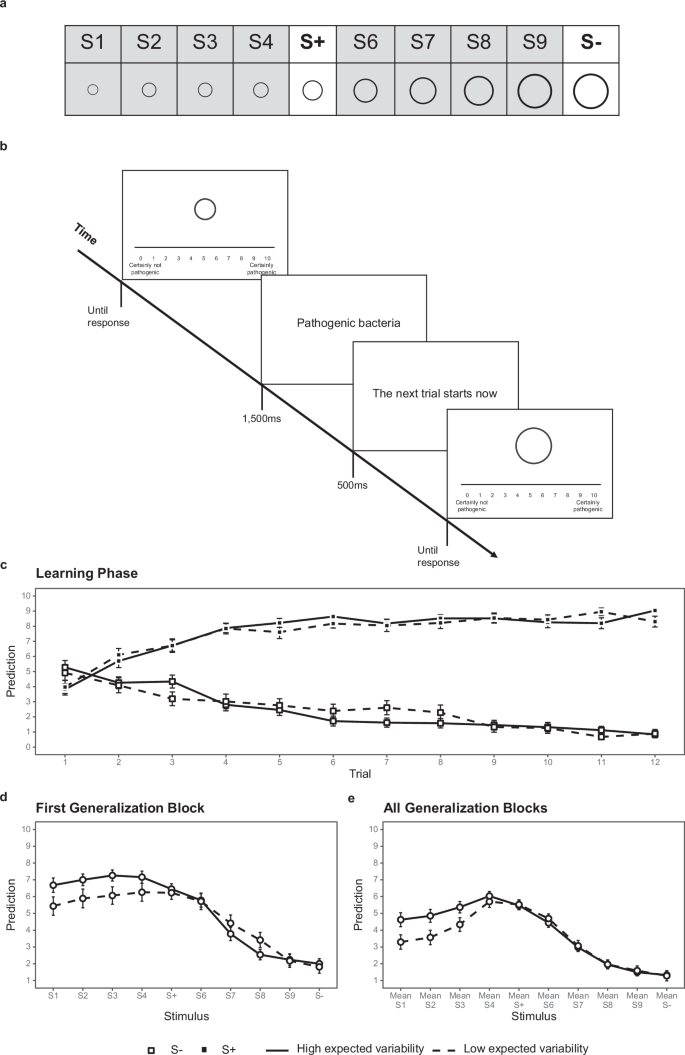

a Stimuli presented in the predictive learning task: S + = a learning stimulus that predicts the appearance of the outcome; S− = a learning stimulus that predicts the absence of the outcome. S = generalization stimuli. The numbers reflect size, from smallest to largest. Note that the hypothesis focuses on S1-S4. b An example of a trial’s sequence: A single ring is presented on the computer screen accompanied by an 11-point rating scale for participants to indicate their prediction of whether it is pathogenic, ranging from 0 (certainly not pathogenic) to 10 (certainly pathogenic). After participants respond, a feedback screen appears, and then a screen announcing the next trial. c Mean outcome predictions (on a 0 to 10 scale) during the learning phase by expected variability, trial number, and stimulus type. Error bars depict ±1 standard errors. d Mean outcome predictions for all rings (1-10) during the first generalization block by expected variability. Error bars depict ±1 standard errors. e Mean outcome predictions for all rings (1-10) during all generalization blocks by expected variability. Error bars depict standard errors ±1.

Results

Experiment 1

In Experiment 1 we showed participants rings of different sizes, told them that the rings represent samples of bacteria and that their goal is to learn to predict which samples are pathogenic (see Fig. 1a). We manipulated expected variability between learning and generalization as well as within the generalization set by telling participants that they will learn with samples from one batch collected by one lab (i.e., from objects that span a narrow range of space and time) and then apply it in a different context, in which samples come from different batches of different labs (high-expected-variability condition) versus in a similar context, in which more samples from the same batch of the same lab (low-expected-variability condition). During learning, a middle-sized ring was followed by the outcome (i.e., “being pathogenic”), whereas a larger ring was never followed by the outcome (see Fig. 1b). During generalization, participants saw rings of varying sizes and indicated their predictions. Importantly, we compared conditions that were similar to each other in both their learning and generalization phases, and only differed in the expected variability between learning and generalization as well in the expected variability within the generalization set.

Learning

Participants learned to differentiate between S+ and S− equally well in the two experimental conditions (Fig. 1c; see the Supplement 1 for full analysis).

Generalization

As recommended by Vervliet et al.4, we analysed both the first block of the generalization phase, which shows effects of learning that are relatively clean of extinction (but suffer from a low number of trials), and the entire generalization phase.

As preregistered, we analyzed participants’ predictions only for the generalization rings located on the side of S+ that is opposite to S− (Rings S1-S4 in Fig. 1a) because these rings allow to test for generalization from S+ that is less influenced by generalization from S−. We used the afex package in R (v1.3-028) to conduct a 4 × 2 mixed-design ANOVA, with similarity to S+ (4 levels, from most similar to least similar to S + ) as a within-subject factor and expected variability (low vs. high) as a between-subject factor. As predicted, we found broader generalization in the high-expected-variability condition (M = 7.03, SD = 1.90) than in the low-expected-variability condition (M = 5.91, SD = 2.53; Fig. 1d, Table 1). Generalization did not change as a function of similarity to S + , and there was no interaction between similarity and expected variability. The predicted broader generalization with increased expected variability obtained also when we examined all six generalization blocks (Table 1, Fig. 1e).

Control variables

There were no significant differences between the two conditions in any of the mood measures or any of the control measures (see the Supplementary Table 9).

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 aimed to examine whether temporal distance between learning and the application of that learning increases expected variability. Building on the context of Experiment 1, we tested whether a long (vs. short) temporal delay between the collection of first and the second batches leads participants to expect higher variability between learning and application of that learning, as well as more variability within the application context. Unlike Experiment 1, this experiment did not examine learning and generalization. Rather, participants only indicated their expectations about the variability of stimuli in the application set when the temporal distance between learning and application was long versus short.

An independent-samples t-test revealed that participants in the distal condition rated the likelihood that the second batch would be different as higher (M = 6.61, SD = 2.61) than participants in the proximal condition (M = 3.88, SD = 1.95), t(89) = 5.57, p < 0.001, d = 2.32. Also, a paired-sample t-test showed that participants agreed with the statement that as the time between the first and the second batches increases, pathogenic colonies with sizes different from the first batch become more likely (M = 6.88, SD = 2.05), than with the statement that they become less likely (M = 3.77, SD = 1.80), t(90) = 8.59, p < 0.001, d = 3.45. Thus, consistent with our prediction, the expected variability was higher when participants expected to apply their learning in the more distant future.

Experiment 3

We reasoned, based on Experiment 2, that when the scope of time that separates learning from the application of that learning increases (i.e., when learning for the distant future), the potential for variability increases as well16,22,23,29. Experiment 3 manipulated temporal distance of anticipated application of learning. Participants predicted the occurrence of a picture of a lightning bolt from rings of different sizes. We told participants in the proximal (distal) condition that they would apply what they learned in the near future, immediately after learning (in the distant future, during a second session). In practice, the generalization phase followed immediately after learning, without any announcement, and was not different between conditions. Thus, participants in both conditions underwent similar learning and generalization procedures and only differed in whether they expected to apply what they learned in the near or the more distant future.

Learning

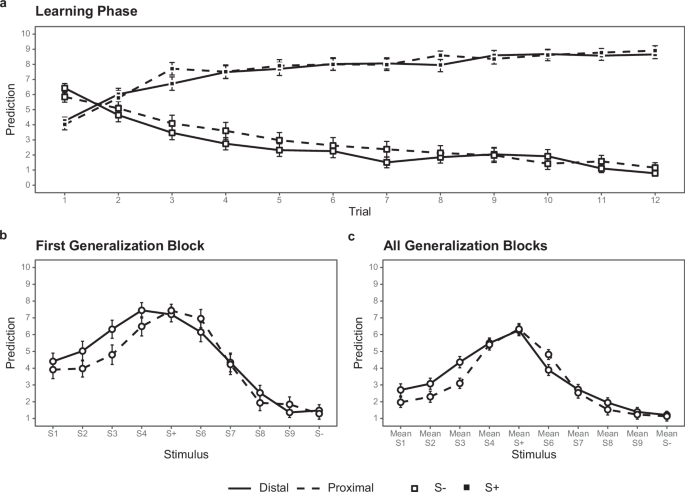

Learning did not differ between conditions (Fig. 2a, see Supplement 2 for complete analysis).

a Mean outcome predictions (on a 0 to 10 scale) during the learning phase by temporal distance, trial number, and stimulus type. Error bars depict ±1 standard errors. b Mean outcome predictions for all rings (1-10) during the first generalization block by temporal distance. Error bars depict standard errors. c Mean outcome predictions for all rings during all generalization test blocks by temporal distance. Error bars depict ±1 standard errors.

Generalization

As in Experiment 1, we analysed both the first generalization block and the entire generalization phase in a 4 × 2 mixed-design ANOVA, with similarity to S+ (4 levels, from most similar to least similar to S + ) as a within-subject factor and temporal distance (proximal vs. distal) as a between-subject factor. As hypothesized, we found broader generalization in the distal condition (M = 5.80, SD = 2.06) than in the proximal condition (M = 4.79, SD = 2.50; see Table 2 and Fig. 2b). A main effect of similarity to S+ indicated that generalization decreased as similarity to S+ decreased. There was no interaction between similarity and distance. These results held also when we analyzed all generalization blocks (Fig. 2c, Table 2).

General discussion

We used a predictive learning task to examine whether generalization would be broader when learners expect more variability between the learning set and the generalization set, as well as within the generalization set. In Experiment 1, participants learned that a bacterial colony of a medium size was pathogenic (S + ), whereas a larger colony was not (S−). At a subsequent generalization phase, they indicated the likelihood that colonies of different, previously unseen sizes would be pathogenic. Colonies were represented by rings, and information on whether a colony is pathogenic was represented by a word. We found that participants generalized more broadly when they were told that the colonies at the second stage come from a more variable environment (i.e., the new samples were collected in different labs) as opposed to a homogenous environment similar to the learning context (i.e., the new samples were collected in the same lab). That is, participants expected more previously unseen colonies to be pathogenic. Experiment 2 showed that anticipating applying learning in a more distant future induce expectation for increased variability. Experiment 3 built on the results of Experiment 2 and showed that expected temporal distance between learning and the anticipated future application of learning broadened generalization. Specifically, we used a task that was a variation on Experiment 1. Namely, the same rings were used, but now at learning a medium size ring predicted a lightning bolt and a larger ring predicted its absence. We found that when participants anticipated a long (vs. short) temporal delay between learning and application of that learning, they generalized more broadly.

We predicted these results based on the notion that generalization involves an accuracy-applicability trade-off, whereby a broader generalization, namely, forming expectations about a larger class of objects, means, on the one hand, that expectations can be formed about more objects, but on the other hand increases the risk that these expectations would be incorrect. We reasoned that when learners anticipate generalization targets to be more variable and more different from the learned objects, they optimize the trade-off between accuracy and applicability by “casting a wider net” attributing the outcome to a broader range of objects.

Our findings are consistent with Construal Level Theory (CLT), according to which people represent objects that are distal in time, space and social perspective in a more abstract way19,20,21. It has been suggested that one of the reasons behind the relation between distance and abstraction is the fact that distance increases the range and variability of possibilities16,22. For example, “a disease I might have a year from now” has more possible manifestations than “a disease I might have tomorrow” and therefore using the broader, more inclusive category “disease” (as opposed to, e.g., “a flu”) would be more appropriate when representing and predicting a more distal state of affairs. Our studies suggest the possibility that when people learn in view of a distal implementation, they represent the learned stimuli in a broader, more inclusive way, which would typically entail broader generalization.

In a recent review on abstraction, it was theorized to occur whenever two subjectively distinct objects are deemed equivalent and therefore substitutable in producing an effect16. If more objects are deemed substitutable with each other, then one can say that more abstraction occurred. For example, if we categorize dieting and exercising abstractly as “ways to lose weight” we deem them equivalent in that respect. If we add to this category also “taking slimming pills” we make that category even more abstract. Importantly, by that definition, generalization is abstraction, because in generalization, two distinct objects are deemed equivalent by the learner, who judges them both as predictive of the outcome.

Our experiments show that learning, and more specifically, generalization may be affected by expectations about application, and not only, as has been shown in past research, by actual experience at learning12,30. Such expectations were induced in our experiments by verbal instructions, and in that our findings are consistent with other studies that demonstrated that generalization is sensitive to verbal instructions31,32,33,34 (for a review see ref. 35). For example, in a study by Boddez and colleagues36, participants first learned to predict an electric shock from a CS (a white or a black square), and then saw generalization stimuli (squares in different shades of grey). Instructions informed participants that the likelihood of receiving an electric shock is lower when the stimulus looks more similar to the CS. In this way, the instructions countered the typical generalization gradient (a tendency to predict the outcome with more likelihood for stimuli that are more similar to the CS). The results indicated that generalization was lower (i.e., lower expectations for electric shock) for stimuli that were more similar to the CS.

Generalization plays a central role not only in classic learning theories, but also in research on concept formation, attitude generalization, and the acquisition of complex knowledge structures. Therefore, our findings may have also practical implications for applied settings such as education, person perception, and clinical psychology (e.g., fear conditioning). Leveraging the insights from the current research may help both researchers and practitioners to design more effective learning and training procedures. Depending on the intended goal — whether to narrow or broaden the extent of generalization — one can strategically adjust the expected variability and expected distance of the anticipated application context. For example, in the context of education, instructors might wish to enhance generalization of acquired knowledge — a process that is typically referred to as “transfer”11,37,38. Research has shown that as learners experience more variability in their educational training (e.g., exposure to different question formats), they exhibit better transfer of acquired knowledge39,40,41. Based on our findings we may predict that the mere expectation of distal (vs. proximal) learning applications will improve transfer. Instructors might strive to enhance transfer by making students anticipate exams that are distant in time and different in context from the learning context – exams that would be administered by a different teacher, in unknown format, and in the distant future. Increasing transfer is a challenge that educators constantly face. Although this is a far implication of our studies, we believe there is a great value in attempting to extend our research into educational setting and more specifically to the hard question of transfer.

An inherent limitation of the predictive learning task we used is that it does not distinguish between two reasons for responding to a novel stimulus in a way that is similar to the learned stimulus42,43,44: First, participants might fail to discriminate between the two (i.e., they incorrectly perceive the novel stimulus as the learned stimulus), and second, they might correctly identify the novel stimulus as different from the learned one, but expect it to result in the same outcome. Of note, those processes are not mutually exclusive, and are both consistent with forming a more abstract category of the learned stimulus, which we and others11 assumed to underlie broader generalization.

A possible way to distinguish between these two options is to measure stimulus perception39. For example, a future study could use a task in which participants decide whether a stimulus is old (i.e., the learned stimulus) or new (a generalization stimulus; see also refs. 45,46,47,48,49), and then perform a generalization task. Would perceptual sensitivity decrease with expectations of increased variability? And if so, would it predict generalization?

A future study could also examine whether expected variability or psychological distance that are introduced after the learning phase, before generalization would increase generalization. If wider generalization emerges also when expected variability or distance are introduced only after learning, it would suggest that expected variability could affect decision criteria.

Methods

All materials, data, syntax and the pre-registrations can be accessed at the project’s OSF page. All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Tel Aviv University and were following the approved guidelines and regulations (Approval numbers 0001956-1 and 0001956-3).

Experiment 1

Participants

One-hundred-and-thirty Mechanical Turk participants completed the study in return for payment. The preregistered sample size was based on power estimation to detect a main effect of condition in the first generalization block based on a pilot study with 24 participants that found an effect size of η2p = 0.47. According to G*power software50, 98 participants are required to achieve 80% power. We factored up by 30% anticipating dropout which might happen in online participation in such paradigms and collected data from 130 participants (we conducted Experiment 3 before Experiment 1, but because Experiment 1 tests the basic mechanism, we present it first.). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions. Per our preregistered exclusion criteria, 34 participants were excluded because they did not reach the learning criterion. One additional participant was excluded because they did not complete the task. The final sample consisted of 96 participants (Mage = 38.54, SDage = 11.78, 52 women) Nlow-expected-variability = 46, Nhigh-expected-variability = 50.

The predictive learning task

In the predictive learning task51 (Experiment 1), participants aimed to learn which stimuli predict a particular outcome. The stimuli were rings of different sizes that, in our modified version, represented bacteria colonies. The outcome was “being pathogenic”. Participants were informed that rings of different sizes will be displayed on the computer screen and that these rings represent bacteria colonies, some pathogenic and others harmless. They were then told that their goal is to learn to predict which bacteria colonies are pathogenic and which are not. Each trial started with the message “The next trial starts now” displayed at the center of the screen for 500 ms. Then a single ring was presented on the computer screen accompanied by an 11-point rating scale for participants to indicate their prediction of whether it is pathogenic, ranging from 0 (certainly not pathogenic) to 10 (certainly pathogenic). Afterwards, the ring and the scale disappeared from the screen, and either the phrase “pathogenic bacteria” or a black screen was displayed at the center of the screen for 1500 ms (see Fig. 1b).

The task consisted of two phases: learning and generalization. In the learning phase, two stimuli were presented (see Fig. 1a), each presented 12 times: a medium-size ring (S + ) and a large-size ring (S−). S+ was followed by the phrase “pathogenic bacteria” in 10 of its 12 presentations. In its remaining two presentations it was followed by a black screen. S− was always followed by a black screen. Once the learning phase was complete, participants were told they will move onto the next phase and feedback will no longer be provided. In the generalization phase, participants encountered six identical blocks in which eight novel rings of varying sizes were presented. In each generalization block, S + , was presented twice, S− was presented twice, and each of the eight generalization rings were presented once. S+ was placed at the center of the generalization dimension, whereas S− was positioned at the right-most edge (see Fig. 1a). Half of the generalization rings were larger than S+ (between S+ and S−). Predictions to these rings could be affected by both generalization from S+ (which would call for enhanced predictions of the outcome, i.e., predicting pathogenic bacteria) and generalization from S− (which would call for reduced predictions of the outcome, i.e., predicting non-pathogenic bacteria). The other half of the generalization rings were smaller than S+ (to the left of S + , in the opposite direction of S−). These novel rings allowed for the examination of generalization from S+ that was less influenced by generalization from S−52,53. Therefore, our (preregistered) hypothesis concerned these latter generalization rings (see S1–S4 in Fig. 1b).

Note that in our experiments, as in previous studies with the same paradigm51,54, S− was the biggest ring, and S+ was a medium-size ring. As in these previous studies, we did not use a condition in which S− is small and S+ is medium, because previous studies found that instead of giving rise to a generalization gradient (i.e., lower expectations with reduced similarity to the S + ), it makes learners increase intensity of response with increasing size (see the review on generalization by Ghirlanda and Enquist55), as if they inferred a rule “the larger the ring the higher the probability of the outcome appearance.”

We operationalized broader generalization as a tendency to predict “pathogenic” for the generalization rings that are smaller than the original learned ring, S+ (i.e., those to the left of S + ). We hypothesized that high-expected-variability (vs. low-expected-variability) would lead to higher predictions of pathogenic quality for these rings.

Procedure

After signing an electronic consent form, an instruction screen informed participants that a number of rings would appear on the screen and that these rings represent various bacteria colonies of different sizes, and that some of these bacteria are pathogenic (i.e., cause a disease) while other are harmless. Participants were told that their goal is to learn to predict which bacteria colony is pathogenic and which is not. The predictive learning task was similar across conditions.

At the beginning of the task, we told participants in the low-expected-variability condition that in the second stage of the task, they would be presented with another batch of bacteria samples from the same lab. In contrast, we told participants in the high-expected-variability condition that in the second stage they would be presented with bacteria samples that were collected by other labs across the world. Upon completing the learning phase participants in the low-expected-variability condition read the following reminder:

Now we will present you with another batch of samples from the same lab. The samples from both batches were collected at approximately the same time and in very similar conditions. Such batches tend to be very similar to each other.

Whereas participants in the high-expected-variability read the following reminder:

Now we will present you with samples from other labs, across the world. When samples of bacteria colonies are transferred between labs, the colonies’ size may get distorted. For example, samples can shrink because of dry conditions and change of pressure. Samples can also expand because of humidity, heat, etc.

Next, participants completed the generalization phase. Upon completion of the task, we asked participants “What was the origin of the samples you saw on the second stage” with the following options: 1) other labs across the world, 2) the same lab as in the first stage, 3) innovative electron microscope, 4) underground research excavations, and 5) skin of laboratory animals. Thereafter, we asked them an open-ended question about what guided their predictions in the second stage. Then, participants responded to the following questions, which served as control variables: interest (“How interesting was the task for you?”), enjoyment (“How much did you enjoy the task?”), difficulty (“How difficult did you find the task?”), motivation (“How motivated did you feel to perform the task well?”), importance (“How important was it for you to perform the task well?”), and perceived competence (“How well do you feel that you did on the task?”) on scales that ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). General mood was also assessed (“Generally, how do you feel right now?” 1 = very bad, 7 = very good), followed by eight specific emotions (“How sad/loose/tense/relaxed/nervous/happy/ joyful/depressed do you feel right now?” 1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Finally, participants indicated their age and gender.

Experiment 2

Participants

One-hundred-and-two Prolific participants completed the study in return for payment. The preregistered sample size was based on a pilot study with 51 participants, in which we found an effect of condition of Cohen’s d = 1.13. We suspected that this might be an over-estimation of the true effect size and opted to detect a medium effect of Cohen’s d = 0.5 in the preregistered experiment. According to G*power software50, 102 participants are required to achieve 80% power with that effect. Per the preregistered exclusion criteria, nine participants were excluded because they failed an attention check and an additional two were excluded because they failed the memory check. The final sample included 91 participants (Mage = 30.22, SD = 5.16, 44 women), Nproximal = 42, Ndistal = 49.

Procedure and materials

Participants were told that the study is about intuitive expectations. After signing an electronic consent form, participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions and read the respective vignette. Below is the text that participants in the proximal condition received. The text for the distal condition appears in brackets:

People are exposed to various bacteria, however, only some of these bacteria are pathogenic (i.e., cause a disease), while others are harmless. Imagine that you are working in a laboratory and test which bacteria are pathogenic and which are not. The bacteria form colonies of different sizes, and their size has to do with whether the bacteria are pathogenic or not. In one sample you looked at, you found out that a colony of the size that is presented here is pathogenic:

You look at another pathogenic colony. It looks like that:

Yet another pathogenic colony looked like that:

The pathogenic colony that you have just seen was from a first batch. In some cases, the second batch is collected soon after the first, while in other cases it might take a full year before the second batch is collected. You now learn that the second batch of pathogenic colonies was collected a few minutes after [a year after] the first batch.

Thereafter, participants were asked how likely the second batch is to be different from the first one and to include pathogenic samples that are different in size. They indicated their estimation on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all likely), to 10 (very likely). Then, as a memory check, participants indicated how much time passed between the collection of the first and the second batches: 1) a few minutes, 2) a few days, 3) a year, 4) 10 years. Finally, we also asked participants to indicate to what degree they agree with the following sentences on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree): 1) As the time between the first and the second batches increases, it becomes more likely that the second sample will include pathogenic colonies with sizes different from the first batch, and, 2) As the time between the first and the second batches increases, it becomes less likely that the second sample will include pathogenic colonies with sizes different from the first batch. These last two questions were preregistered as exploratory measures.

Experiment 3

Participants

One-hundred-and-twenty-six online participants were recruited by an online Israeli platform (“Midgam”), completed the study in return for payment. The sample size was based on the recommendation of Ledgerwood56 for experiments with unknown effects. We originally planned to recruit 50 participants per condition, but anticipating exclusions due to low performance, we recruited 60 participants per condition. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental conditions. We excluded 34 participants because they did not reach the learning criterion. The final sample consisted of 92 participants (Mage = 25.32, SDage = 2.70, 44 women) Nproximal = 45, Ndistal = 47.

Procedure

The experimental procedure and stimuli were similar to Experiment 1, except for the framing of the task, the outcome that was predicted and the way generalization was introduced. The experiment was presented to the participants as a study on learning and personality. After signing an electronic consent form, the instructions screen informed participants that a number of rings would appear on the screen and that some of these rings would be followed by a lightning bolt. They were told that their goal was to learn which ring would be followed by the lightning bolt. Unlike Experiment 1, the 11-point scale ranged from “Certainly no lightning” (0) to “Certainly lightning” (10). We manipulated the temporal distance of anticipated application of learning by telling all the participants that they will first do a simulation of the actual task, and then manipulating between conditions the time of the anticipated actual task. Specifically, we told participants that the actual task will follow either immediately after the simulation (in the proximal condition) or a week later (in the distal condition). In reality, there was no “actual task” and in both conditions we were interested in participants’ performance of the ostensible simulation, which was (except for the timing of the anticipated actual task) identical in both conditions, and which presented learning and generalization one after the other, with no break and no specific instructions between them.

Participants in the distal condition read the following:

The following study aims to test the effect of personality on performance in a learning task. The study includes two parts – the first part will occur now, whereas the second part will take in a week from now.

In Part 1,now, you will do a simulation of the learning task.

In Part 2,next week, you will do the actual learning task and answer personality questionnaires.

Participants in the proximal condition read the following:

The following study aims to test the effect of personality on performance in a learning task. The study includes two parts – the first part will occur now, whereas the second part will take in a week from now.

In Part 1,now, you will first complete a simulation of the learning task, and the actual task will follow.

In Part 2, next week, you will answer personality questionnaires.

Participants in both conditions read that the personality assessment would take place in the next session, a week later, to make sure that participants in both conditions expect a two-part experiment. In fact, participants in both conditions completed the predictive learning task (which they thought was the simulation of the actual task) in the first session, and a short version of the Need for Condition questionnaire (NFC57) the week after. We included this questionnaire to lend credibility to our cover story that the second part of the experiment involves personality questionnaires. We chose NFC because we thought that it might be related to learning and to generalization, but we did not predict it to moderate or mediate the effect of distance. We found that high NFC was associated with less generalization and was unrelated to learning. The effect of distance on generalization remained significant after controlling for NFC (see Supplementary Materials).

Upon completing the predictive learning task (i.e., the ostensible simulation), participants answered a demographic questionnaire. After a week, we invited them to participate in the second part of the experiment, in which they answered the NFC questionnaire.

Responses