Applying multispecies justice in nature-based solutions and urban sustainability planning: Tensions and prospects

Introduction

Nature-based solutions (NBS) (e.g., green walls and roofs, stormwater wetlands, grassland/meadows and forested areas) provide a plausible way of regenerating and conserving nature in cities that can support social, ecological and economic co-benefits for humans and other species1,2. NBS research and practice have been widely applied to tackle various environmental issues, mitigate the impacts of climate change, foster sustainability transformations, as well as scale-up techno-ecological innovations to address societal challenges3,4. However, complex trade-offs exist between the social, economic and ecological impacts of urban development and urban greening on people and nature. For instance, green regeneration can lead to distributional inequalities of NBS co-benefits across vulnerable, middle-class and wealthy groups of people (see ref. 5 for a review). To address these justice concerns, research has increasingly focused on unpacking procedures that actively promote the participation of vulnerable groups in decisions, whilst ensuring their exclusion is avoided. Whilst innovative multi-level governance approaches have been offered to begin to address these justice concerns6, the measures used have often been reduced to a set of ‘simple and reducible shorthands’ such as measuring progress towards achievement of just outcomes, or increasing the number of people involved in NBS planning. In particular, such measures fail to address more nuanced questions such as ‘what is more or less just?’ and ‘who gets to define this?’7.

The question of ‘justice for whom’ extends beyond human subjects to include other species and thus raises critical questions about how humans relate with urban species, ecosystems and one another in the face of rapid urbanisation and biodiversity loss. The impacts of climate change on all species further highlight the interconnectedness between human and non-human justice outcomes8. Yet the needs of other species are poorly or misrepresented in NBS planning, giving rise to ecological justice issues9,10. For example, in Melbourne, Australia, exercises that map social-ecological justice highlight that areas of high ecological value have been earmarked for urban or industrial development11, eroding ecosystem capabilities and ecological agency9. These areas also present social deprivations, highlighting how unjust processes and outcomes intersect across human and ecological communities, all which occur partly because of unfair planning processes and goals.

Addressing issues of ecological injustice can take on many forms. Grabowski et al12. show the different ways of incorporating ecological justice in NBS planning, including by making space for ecological communities, rivers and waters (e.g. a policy strategy to physically and ethically provide support for a river in the Netherlands to ecologically self-assemble); by reinstating indigenous approaches to ecological governance; supporting community-based cultural and political institutions advocating for ‘socio-ecological self-determination’; and enabling intersectional efforts to green existing grey infrastructure. More broadly, Maller13 invites us to consider how more-than-human thinking can enable political processes of relationality. This process would require including and formally recognising Indigenous knowledge systems that are centred around practices that recognise “multiple more-than-human subjectivities, agencies and personhoods” (p. 5). For example, in New Zealand, co-governance arrangements have been established where Māori and the Crown share decision-making power or where Māori exercise a form of self-determination on the co-management of resources (such as rivers and mountains), the provision of social services to Māori by Māori-focused entities, and the guaranteed inclusion of Māori in local governance14. Recent research at the international science-policy interface calls for a shift from a mindset of us and them, commonly presented in arguments justifying anthropocentric or biocentric framings of NBS and justice, to a more pluricentric concept of justice grounded in ‘all of us’15,16,17, including a shift in thinking and practices about human relations with other species18,19.

This paper aims to extend the dominant thinking about what constitutes ‘justice’ in the context of NBS and urban sustainability planning by drawing on the concept of multispecies justice (MSJ) that originated from political science, critical animal studies, posthumanist and feminist studies. MSJ thinking views humans as part of larger ecological systems, which in the context of planning processes would require the prioritisation of the well-being of all species within urban areas20,21,22. We argue that such considerations constitute a new frontier for NBS scholarship. We propose to move beyond current definitions of justice that are solely focused on humans, to provide a new conceptualisation of what ‘justice’ might mean from a multispecies perspective. First, we define MSJ and its theoretical anchors in the context of representation, distribution and agency. We then provide exemplar cases demonstrating the tensions and prospects for more fully considering these three elements of multispecies concerns in NBS governance and urban sustainability planning. Finally, we identify future research directions to address the identified challenges and mainstream MSJ perspectives in NBS.

Attending to multispecies justice in nature-based solutions planning

Multispecies justice (MSJ) not only considers the ‘justice claims’ of humans and other animals, but also the claims of plants, forests, rivers, soils and broader ecological systems, thus emphasising the relational webs in which they exist18 and their inextricable connection to the places in which they are located23. This relational and situated view of justice challenges conventional justice boundaries that exclude other species and ecosystems as subjects of justice due to their incapacity to make their needs known. A MSJ perspective recognises that these subjects can be unjustly harmed, and to whom moral obligations are owed through our relational embeddedness18,24. Importantly, a relational perspective of MSJ extends beyond ecological relations, to include the intersecting historical, political, economic, social and cultural relations produced by e.g., colonialism, capitalism and racism, and impact humans as well as other species and ecosystems25. By considering these complex, intersecting relations, MSJ broadens the scope of justice to include both ecological and socio-political dimensions, making it a more inclusive and holistic approach to addressing justice issues.

A relational approach to research on humans and other species took hold as part of the so-called “animal turn” in human and social sciences in the early 2000s26. A justice focus began with work on ecological justice27,28, and the first mention of the term MSJ can be traced to the 2008 book “When Species Meet”, by the philosopher Donna Haraway29. In the first two decades of the 21st century, the field of multispecies studies30 expanded with theories of MSJ25, sometimes connecting and sometimes not to a variety of offerings across e.g., cultural anthropology31, cultural geography, philosophy and law32, political theory28,33, feminist and ecofeminist theory34, Indigenous studies35, and conservation science13. The “multi” in MSJ refers not only to multiple species and subjects, and life-supporting systems, but to the multiplicity of ways of being across disciplines, knowledge systems, and levels of vulnerability, and denotes an approach to justice that cannot be pinned down as a singular, universal theory23.

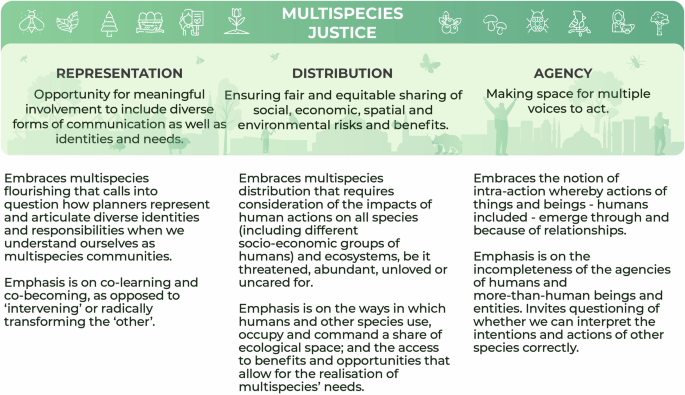

It is neither possible nor necessary to wait for a consensus on what MSJ is to engage in the process of experimentation and transformation. As part of this process, MSJ requires us to consider conflicting needs that arise because of relations embedded in representation, distribution, and agency (Fig. 1). We recognise that these three dimensions of justice do not provide an answer to what is just or not, but provide one way of thinking and operationalising justice which allows us to explore how NBS planning can embrace MSJ as a process and practice. Issues of discursive power (the role of discourses and knowledge on worldviews and values), framing power (how the relationships among people and nature are understood), rule-making power (the power to make rules), operational power (possession of informal or formal rights to nature) and structural power (the historical systems which reproduce social hierarchies and divisions between human and other species’ rights) directly and indirectly influence how representation, distribution and agency are considered in specific planning contexts36.

Conceptualisation of MSJ as applied to NBS planning.

Multispecies justice and representation

Representation is traditionally considered as recognitional and procedural justice. Representation, in the context of MSJ, concerns the extent to which opportunities exist for the diversity of human and other species to be recognised and meaningfully involved in decisions. A broader consideration of representation in NBS as a means for more sustainable urban development raises questions about for whom the city is planned37,38, about who is involved, whose interests are directly represented in planning processes and how these interests inform the final planning outcomes39. Evidence suggests that NBS in urban areas can support climate mitigation, biodiversity conservation, and human well-being outcomes40,41.Yet despite strong policy statements (e.g., UNEP/EA.5/Res.5) that suggest that NBS should provide benefits for biodiversity, in certain contexts nature is narrowly commodified into ‘sustainability fixes’ that support entrepreneurial and engineering city regimes42.

MSJ scholarship enables NBS planners to rethink the exceptionalism of the human position in planning and provide for inclusive, ethical relationships grounded in the idea of multispecies flourishing. This helps remove deeply ingrained boundaries between humans, the economy and other species. Multispecies flourishing calls into question how planners represent and articulate diverse identities and responsibilities when we understand ourselves as multispecies communities43. It enables us to think about how we, as humans, are emergent in the relationships between social and physical elements of the city, including awkward relationships between humans and ‘undesirable’ species such as mosquitoes, midges and garden slugs44. Accepting such relationships requires planners to move beyond discourses of ‘NBS co-benefit’, ‘risk’, ‘vulnerability’ or ‘resilience’ where there is an emphasis on intervening or radically transforming the ‘other’. In contrast, it requires a commitment to multispecies relationships of responsibility and care45, reflected in the practices of co-learning and co-becoming (see Case Box 1). Co-learning may be facilitated through the development of “arts of noticing”31 or “arts of attentiveness”30. For example, participatory theatre has been used to set up a “Parliament of the Species” to facilitate participation in planning46 or the creation of new ‘spatial imaginaries’ that foregrounds how thinking with (rather than only thinking about) how other species are represented in planning47.

Case 1: Representing more-than-human relationships with novel ecosystems

The City of Curridabat in Costa Rica, has, in the last decade, undergone a city and institutional transformation as a response to growing social and ecological challenges, such as formal and informal urbanisation, climate change, deep social inequalities, loss of biodiversity, and an unsustainable planning model. A new planning paradigm named Ciudad Dulce (Sweet City in English) prioritises biodiversity conservation, multispecies interactions, and enables social-ecological-political spaces of collective design and creation48.

This city model envisions sensitivity and receptiveness towards all living beings as fundamental to transforming the well-being of people and all living beings49. To foster representation, this vision went through a process, first of self-recognition, in which the municipality recognised the need to reimagine new institutional arrangements, and then of fostering reciprocal recognition. This reciprocal recognition situated the experiences of humans and more-than-humans as central to urban planning and design. The Municipal Strategic Plan was modified to position pollinators, earthworms, drops of water, güitite (flowering plant), hummingbirds, and all other species including humans as active community members and co-shapers of the landscape, entangled in the production, creation and maintenance of a healthy city that provides nourishment and wellbeing to all49. A central archetype to the Sweet City model was the lives of the pollinators, specifically the native bee. Using pedagogical methodologies and methods of co-learning, the municipality and communities explored questions like “how are bees experiencing the city” and “how can this be changed to improve multispecies wellbeing in the future”? This co-learning and experiential model of planning created a series of ideas of how humans and native bees could co-habit urban areas50. To ensure that this institutional transformation was reflected in the urban governance model, the Municipal Strategic Plan was reformulated to include this methodology and the city’s vision during the new political cycle of 2015. The challenge of giving other living beings and systems a voice was addressed by creating a pedagogical Centre of Territorial Intelligence for Biodiversity in which species needs and interests are collected in this space as a tool to encourage regeneration of species and ecosystems, understand their climate adaptabilities and develop new ways of caring and interacting that can assist the regeneration, as in multispecies flourishing, in disturbed landscapes (H. Mendez, personal communication, April 30, 2024).

This city model was not only a socio-environmental and urbanistic project to implement NBS and address urban sustainability, but a political-ethical vision rooted in a mutual recognition of the value of all forms of life. It showed that different questions need to be asked to achieve a truly sustainable city. This pedagogical approach has started to shift perceptions in the community, with children now discussing how planning is not only for humans, but for other living beings too (H. Mendez, personal communication, April 30, 2024). This has created “a language that is capable of prompting recognition of similarity and responsibility, between embodied, social creatures”51 (p.5). By changing the Municipal Strategic Plan, municipal services and projects are now designed to improve the experiential qualities of its city inhabitants. For example, rather than designing NBS to address only a few specific challenges (e.g. flooding or heat), it now must address a wider range of considerations that include the experiences of people, other living beings and planetary systems. However, political and social barriers persist. Recent endeavours to integrate the ‘rights of nature’ into the municipal normative framework as a step to consolidate a multispecies normative framework have currently been halted (H. Mendez, personal communication, April 30, 2024).

Multispecies justice and distribution

Environmental justice in NBS research has mainly been framed in the context of distributive justice, referring to the (un)fair distribution of environmental assets and risks or harms with respect to their access, allocation, quality and quantity, both now and historically5,28. For example, deprived communities are generally more exposed to environmental hazards, have fewer environmental amenities and are more adversely affected by green strategies52. Many NBS planning strategies aim to improve environmental justice outcomes by improving the quality of and accessibility to green spaces. For example, the UK Government has a policy that aims to ensure that everybody has access to green space. This policy requires that at least two hectares of accessible natural greenspace is made available per 1000 of the population according to a system of tiers: i) no person should live more than 300 metres from their nearest area of natural greenspace; ii) there should be at least one accessible 20-hectare site within two kilometres from home; iii) there should be one accessible 100-hectare site within five kilometres of home, and: iv) there should be one accessible 500-hectare site within 10 kilometres of home53. However, the creation or restoration of NBS for environmental amenity can lead to green gentrification, and situations where lower-income populations are denied access to the benefits of urban life54. Similarly, greening driven by gentrification or affluence to capital (revitalisation efforts etc.) can skew the distribution and type of habitats towards where there is money rather than sites with high social-ecological potential.

A shift to distributional justice through a MSJ lens requires consideration of the impacts of human actions on all species (including different human groups) and ecosystems, be it rare, abundant, unloved or uncared for. Distribution, from this perspective, is concerned with equitability between human and nonhuman interests when assessing the spatial distribution of environmental bads and goods55. The concept of ecological space, comprising of all environmental goods and natural resources that play a part in socio-economic life56, can be used to connect theory on multispecies and distributive justice57. Emphasis is given to: (i) the ways in which humans and other species use, occupy and command a share of ecological space and functions; ii) the processes that lead to the creation of ecological space; (iii) the degradation of ecological space, and iv) ‘being in’ ecological space (the notion that humans not only use but also are themselves ecological space, which breaks down human-nature dualisms). For example, the many species that live on us, or live in symbiosis with us during our lives (Case Box 2).

Similarly, a capabilities account of justice can be applied to understand distributional impacts. A capabilities approach, developed by Sen58 and Nussbaum59, focuses on the basic capabilities, or needs, necessary for a functioning life. For Sen, these are basic political and economic freedoms, to be defined by public discourse. For Nussbaum, they are a set of predetermined basic needs to be protected by constitutional rights. From a distribution point of view, the focus is on providing a basic minimum, or threshold, of capabilities that provide for a functioning life – justice is both that provision and the avoidance of undermining such functioning. Nussbaum60 extended this approach to include a number of more sentient animals, while others have used it to argue more broadly to protect and provide for the basic capabilities of ecological communities and systems to function28,61.

Case 2: Rethinking ‘green factor schemes’ for (re)distribution of NBS and their benefits and costs

As a NBS planning strategy, the green factor tool helps urban and landscape planners to calculate and ensure a desired level of greenery when building new lots in urban environments by offering a numeric value describing the ratio of the scored green area to a lot area62. The tool was originally developed in Berlin, Germany and it has been further developed in Sweden and the United States62 and has especially been applied when building new lots.

Green factor has been used in Finland in new development projects for some years. A detailed impact assessment ordered by the City of Helsinki63 shows that the usage of the tool has become established, especially in plans for residential lots. Lots, where green factor has been used, have high multifunctionality and a high level of green elements. For example, the tool has ensured minimizing the degree of sealed or paved surfaces, saving many existing trees during the construction process and it has also supported the introduction of trees and plants that produce edible fruits or flowers. Additionally, spaces for interaction and community building, or recreation (e.g., play or sports areas) have increased. In general, the assessment shows that the green factor tool has had a positive impact on the distribution of NBS. However, in wider common yard blocks consisting of several lots, the green factor tool can lead to an unbalanced spatial distribution of the benefits of NBS. Experiences from housing exhibition area Bo01 in Malmö, Sweden report that certain green spaces became very popular after the areas were built with green factor and in some areas the residents resisted turning a lawn to a more biodiversity-rich meadow in order to have space for recreation64. Assessment showed that in most cases the lots in Bo01 could host rich biodiversity with little cost and effort. Another concern relates to the fact that the green factor tool is used primarily for new built areas that tend to attract already privileged groups of people.

Considering the ways in which humans and other species use, occupy and command a share of ecological space, the green factor tool has created a new awareness of (re)allocation of costs and benefits of NBS in spatial planning and increased biodiversity in urban landscapes, as well as shed light on implicit power dynamics. Yet, the green factor tool still overlooks interspecies concerns19, including possibilities for recognising the capabilities of diverse other species. Recently, the city of Espoo in Finland developed a biodiversity calculator for the green factor tool with the aim of increasing urban biodiversity. It targets attention to measures that, for example, replace alien species with planting of wild species65. Further, the green factor tool does not allow for active participation of local communities. Incrementally developing the green factor tool to include both richer biodiversity along with community engagement process would guide urban green infrastructure planning and design to better account for the distributional needs of diverse people and other species43. Doing so could foster thinking about how diverse residents and other species share ‘being in’ ecological space and how they foster NBS planning with emphasis on care-making practices57.

Multispecies justice and agency

Taking humans and other species seriously as subjects of justice not only requires processes that take them into consideration (as one sees in, for example, animal welfare laws or most environmental regulations) but also recognising them as subjects of justice. This recognition of subject status implicates the idea of agency in two senses. First, multispecies others are agents, where agency is understood in the broad sense of having effects on the world, and that their agency matters morally. The morally significant agency is possessed by all living subjects like humans and other animals, but also by viruses, stones, or tornadoes66. From this follows the second, political sense of agency, whereby beings are entitled to recognition, and to being part of the community of decision makers67.

Discussions about human agency in the recent literature on NBS highlight the emergence of agency through co-production processes68 and stewardship practices guided by capacities like hope, care, compassion, interconnection and a sense of community69. Other species have been understood as critical contributors to ecosystem functions – functions that are essential for the solutions sought by humans. While this understanding positions other species as involved in co-creating their own environment, it is still focused on the aspect of multispecies agency that contributes (or counters) to human pursuits and interests. A MSJ approach requires that the agency, contribution and hence inclusion of multispecies others are justified in their own right.

Some of the NBS literature has begun to venture beyond the focus on human agency. The ways in which other species have thus far been recognised as having agency is through the ways in which they respond to, and repurpose the built environment conceptualized as co-creators or “ecosystem engineers”70. Using beavers as an exemplary species, Welden71 discusses three levels of conceptualization for the agency of other species in planning and urban life: labourer, co-worker, and community. She argues that the current NBS literature recognizes more-than-human agency at the level of labourer or co-worker. Even NBS that directly engage with the lives of more-than-human species, such as the strategic placement of goats to keep vegetation levels down to prevent wildfires, the animals become an exploited technology to secure and protect human interests. Welden suggests that conceptualizing more-than-human life as part of a multispecies collaboration would open pathways for the critical development of NBS.

The idea of planning for multispecies collaboration steers away from focusing on agencies as lodged within individuals, to listening and being with as alternative ways of recognising multispecies agencies. MSJ moves us beyond the question of whether we can interpret the intentions and actions of other species correctly, and instead posits us humans as ecologically reflexive community members. This may take the form of striving to become spokespersons46 or seeking to take the perspectives of other beings through attentiveness, interaction and collaboration72. Importantly, a relational and agentic understanding of humans and other species has existed across different Indigenous people and cultures worldwide47. The emergence of this thinking in academic discussions and the claim that it represents a new insight is thus often criticized for re-enacting colonialism73. An ethical approach to contemporary developments in multispecies planning and design involves acknowledging that the ontological base of relationality is longstanding in many cultures18.

The arts and technology have also been key in understanding human and more-than-human agencies. For example, creating a digital archive of future scenarios in which other species are entangled with human infrastructures (industrial farming, water-waste management or transportation services) makes it evident that humans are not the only species that shape the future47. What the framework of MSJ brings to this observation of the already existing presence and agency of more-than-humans, is the ethical imperative to ask questions about how present and future infrastructures are entangled with multispecies lives, and the degree to which they enable or impede their capabilities, functioning, and flourishing. When using emerging technologies, MSJ can help us consider and trace more-than-human relationalities in ways that will counter the forms of exclusion that render the current situation systematically unjust for certain beings, human and not. For example, integrating technology to facilitate communication and collaboration between humans and other species, such as using sensors to monitor environmental conditions and adjust urban infrastructure accordingly, or creating interfaces for humans to understand and respond to the needs of urban wildlife.

Case 3: Developing attentiveness to more-than-human agencies in everyday urban surroundings through socio-ecological community science

Two interlinked community science projects in Finland named Citizens with Rats (2020-2024) and Fellow Feelings (2021-2025) collectively engaged more than 100 young people (13-18 years old), researchers of education, sociology and ecology, as well as artists (speculative fiction authors and bioartists) over three years to explore how to develop attentiveness to the unrecognised agencies of humans and other species in urban communities. The problem that these projects addressed is that human children share the predicament of many humans and other species in that they are heavily affected by the current ecological crises but have no or very little democratic voice in debates about the future of the planet. While recent surveys show that young people in Finland and elsewhere in Europe have faith and optimism towards the future in general, their sense of agency in relation to environmental and societal changes is low74,75. They also share a feeling of not being heard or taken seriously unless they reach an exceptional role model status like Greta Thunberg.

To address this double exclusion of experienced lack of agency of young people and unrecognised agencies of more-than-human community members, the projects included phases of ecological fieldwork, ethnographic observation, and artistic re-imagining. The young people engaged in these phases as part of their schoolwork related to exploring their neighbourhoods and suburbs. The focal species in each project were ones that represented the unloved or unknown others: rats and the dark taxa of gall midges (Cecidomyiidae), respectively.

Working with ecologists, ethnographers, artists and individuals of the target species, the young people were familiarised with different ways to generate knowledge of their surroundings, ranging from seemingly objective protocols to speculative storytelling and approaching the perspectives of other beings. Through tasks of counting rat tracks or finding gall midges, microscopy and DNA sequencing, photographing, walking-observations, storytelling or empathetic imagining, they were encouraged to identify diverse modes of agency not only locating agencies to more-than-humans but also reconsidering agencies as distributed and shared, as potentialities that actualise differently in different assemblages of humans, other life, built, planned and natural surroundings. Through working with multiple perspectives, interests and ways of knowing, the students learned how to attend to the co-constitution of our human lives and the lives of those around us that we might not notice or try to actively avoid. They came to appreciate and empathetically relate to the viewpoints and preferences of other beings in their urban surroundings. They learned how to re-imagine futures co-habited with other species. Involving humans and other species in urban space planning was expressed in their final speculative fiction pieces: for example, scales of buildings and infrastructure not only took other species into consideration but sometimes overruled human preferences.

This type of work has specific implications for NBS and urban planning. As discussed earlier, once the agency and moral significance of multispecies others are recognised as part of the collaboration and co-shaping of shared space, it provides the political space to include the interests and needs of multispecies others in decision-making processes. Doing so justly also requires paying attention to the intersections of cultural, historical and political forces – including NBS and urban planning – that shape the possibilities for all beings but tend to erase the lives and needs of certain species, while highlighting and protecting the interests of others. Not only epistemic barriers, but cultural preferences and histories will make the inclusion of those who are unfamiliar or unwanted by us, in this case rats and gall midges particularly challenging to include. In recognising this, planning practices could be developed to encourage reflexivity and explicit analysis of how existing power relations operate, to shape different lives across multispecies communities. They could also be developed regarding their potential to create these communities more justly through constructive appraisal of diverse agencies: making visible the needs of other species and underrepresented groups of humans. This could potentially impact environmental literacies of human communities and create more compassionate communities through materialising expressions of care.

Widening understanding of MSJ in NBS and urban sustainability planning: Opportunities and challenges

As an interdisciplinary group of researchers, we identified opportunities and challenges when exploring representation, distribution and agency in NBS and urban sustainability planning using the ideas of MSJ. MSJ can offer diverse avenues for implementing NBS, ranging from initiatives operating within the existing system to those outside of it. However, some advocate for a radical overhaul of the capitalist neo-liberal management principles, viewing the system itself as inherently unjust and in need of dismantling through a justice-oriented lens, potentially rendering current NBS efforts ineffective76,77. Conversely, incremental adjustments within the system could be advocated through reforming existing NBS, environmental regulations, and policies. It is from this perspective that we offer some guidance as to how to move forward as an interdisciplinary community of NBS and MSJ scholars and practitioners, although an incremental path may also open possibilities for radical changes.

Moving beyond the limitations of existing standards for biodiversity conservation

Existing standards that underpin biodiversity conservation policies tend to prioritise native ecosystems and threatened species. For example, the Convention on Biological Diversity’s ‘Biodiversity Plan for Life on Earth’ (Target 4) predominantly focuses on the recovery and conservation of threatened species78. A similar focus is also found in the guidance for the use of IUCN’s79 Global Standard for NBS. The implication of the above is that such policies fail to provide justice for non-threatened species.

Through its embrace of diversity of value and its broader focus on representation, a MSJ perspective could constructively question existing standards and classification systems in biodiversity conservation, enabling a deeper discussion of how those standards have come into being and the interests in which they serve. In particular, it could provide a way for recognising neglected and overlooked systems and species not currently covered by environmental regulation, such as abandoned industrial areas and small neglected strips of vegetation in places like train yards or road verges. Such representation could result in the recognition and conservation of a more diverse range of taxa such as novel urban ecosystems thriving in areas where environmental thresholds have been exceeded. Additionally, a MSJ perspective could provide a framework for considering novel species assemblages. For example, it may help identify and develop actions to assist those species that need to move to new locations due to rapid climate change, but are unable to do so80.

An MSJ perspective may also stimulate a rethink of definitions of rare and threatened species and habitats. Current strategies to protect rare and threatened species are often skewed towards more charismatic species81. For example, in some countries threatened species assessments have led to different taxonomic groups receiving different listings, with mammals commonly receiving the highest likelihood of listing82. There are also considerable differences in red-list assessment coverage between species groups: many animal groups, especially vertebrates, tend to be comprehensively assessed, while groups like plants, invertebrates and fungi remain under-assessed83. Whilst a focus on the more charismatic rare and threatened species may be justified, it does raise concerns that justice for most other species who share the planet with us is disregarded. For example, the critically endangered Imperial woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis) rightly deserves special concern in conservation policy, but should such policies not also consider the justice concerns of the common rock pigeon, or a little known arthropod or the pig 81? An MSJ approach does not call for the same treatment for all, however, it does highlight the need to critically examine whose interests we prioritise, whose interests are at work in setting these priorities, and what perspectives are marginalised and devalued and thus rendered invisible. It attends to the suffering of wildlife individuals alongside efforts to protect collectives, and the moral responsibility we as humans have to other species and the environment. Examples of urban planning that take other species into consideration, regardless of their status of endangered-ness, include guidelines and requirements for building bird-friendly glass surfaces, in place e.g., in the city of Helsinki in Finland.

New monitoring and evaluation frameworks are needed for integrating MSJ perspectives into ecological restoration initiatives for wider notions of representation, distribution and agency to take hold within the logic of target-oriented planning and management of NBS. This will require a commitment from post-humanist scholars and natural scientists to work together to create new sets of indicators of conservation effectiveness that cater to interspecies concerns.

Embracing MSJ as a process and practice

NBS planning is a highly interdisciplinary field that engages scholars from ecology, governance, political science, engineering and beyond. Emphasis is on how NBS are planned, designed and implemented by diverse groups/individuals, at different stages, most of the times generating a mismatch between the key promises of NBS (democratic co-designed solutions that through innovative solutions address grand challenges) and the reality of how NBS are implemented in practice84. The diverse actors/groups involved in NBS planning are all trained within their own disciplinary conceptions and assumptions; for example, a strategic planner is embedded within a governance system of regulations, bureaucratic processes and checklists that impede creative thinking and solutions.

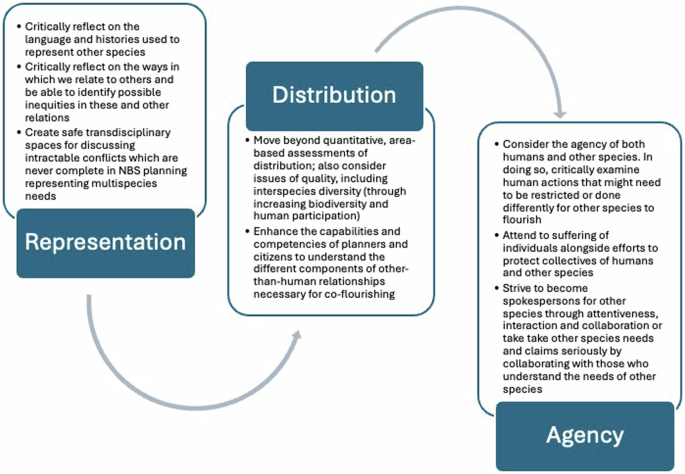

MSJ scholarship provides a way of viewing NBS planning as a process or practice (Fig. 2) rather than a set of ‘outcomes’ or ‘benefits’. It recognises the complexities of achieving any given outcome or ‘solution’ and humbly recognises that MSJ decision-making will also comprise trade-offs because of the complexities and histories embedded within the cities we live. As a principle, MSJ insists that the interests of all those affected by decisions be actively considered in decision-making processes, and that being human should not act as a criterion for inclusion, as it currently does. How this principle is operationalised is a question that requires further experimentation and research on the effects of different types of models, including having proxies and deliberative processes that foster ecological reflexivity85. Such experiments will need to test alternative options that explore various questions, including who is best placed to represent others’ interests, what types of practices of attention, interaction and collaboration can produce the best knowledge about other species’ interests, how those interests can be most effectively communicated, who or what to include (biocultural relations, ecological systems, species, individual animals for example, and how conflicts amongst other species can be justly navigated. The argument that the inclusion of other-than-humans multiplies complexity and conflict needs to, however, be recognised as a practical question to be addressed, not a normative one, as the ethical case for multispecies inclusion in decision-making is unaffected by the difficulties stemming from conflicts.

Factors to consider when viewing MSJ as a process and practice in NBS planning

When considered as a process and practice, MSJ enables its practitioners to question core assumptions underpinning NBS planning. For example, the language used to classify species (e.g., invasive vs. threatened) and whether and how humans are biassing the representation, distribution and/or agency of a given species over another. It provides a generative interdisciplinary planning space to critically and constructively reflect on which species and ecosystems and groups of people are being highlighted, ignored, and being invisibilised, and why. For example, climate change will change the needs of different species over time, as well as the combinations of species and ecological systems within which decisions need to be made. Viewing MSJ as a process and practice supports critical reflection on whose ‘voices’ may need to be prioritised in the face of external pressures. For MSJ to be mainstreamed into NBS planning, new guidance will be needed on how to apply MSJ principles across different fields of planning (strategic, land-use, and other specialisations), architecture, engineering, and other fields that are directly involved in actively shaping urban landscapes. Future research could consider developing a system of ‘response-ability’ within MSJ NBS planning that emphasises differing care-making practices (building on86).

Building and strengthening the capacity of NBS planners to work with MSJ

The wider focus on representation, distribution and agency of the MSJ perspective presents additional complexities to planners, potentially impeding the upscaling of NBS. New tools are needed to show how MSJ can be integrated into different scales of planning, and to bring reflexivity in the daily practices of governance work that is situated in specific contexts and supports the experiences and needs of planners. Enhanced reflexivity will be important in the NBS implementation process design phase1: stakeholders will need to be carefully identified to not only represent the human benefits derived from NBS, but also to effectively speak on behalf of the concerns of other species. Reflexivity is also important in the NBS monitoring and evaluation stage, for example, being cognisant of the representational or distributional biases inherent in certain indicators or methods of NBS co-benefit assessment.

Another concern is that planners may feel powerless because they are embedded in a system that is made up of a mesh of complex technicalities, bureaucracies, rules and ‘ways’ of doing that hinder innovation and practices that support MSJ concerns. More just futures for all forms of life that enable them to flourish on Earth require shifting away from techno-fixes and nature-culture dichotomies that foster divisions between humans and other species. It also requires a more detailed examination of who creates the rules and frames the narratives, why and how these are sustained regarding biodiversity conservation and NBS planning. While new forms of agency and ways of attending to the communication of other-than-human beings must be included in urban planning, the capacities of planners to apply MSJ to specific planning and policy challenges also needs to be built through new education and awareness-raising programs. For example, including MSJ in ‘planning’ degrees, offering short extra-curricular courses on MSJ, connecting MSJ to new and emerging regulations, and developing activities for schools and community groups to actively engage in felt experiences to show how other species can be represented in NBS planning and environmental decision-making processes. MSJ could, even if they need to be constantly adapted and renegotiated, offer new standards for how to create policies to address multispecies needs.

Responses