Assessing competence of primary care respiratory healthcare professionals to deliver a psychologically-based intervention for people with COPD: results from the TANDEM study

Introduction

Management of long-term conditions and their associated multimorbidity is a major challenge in today’s community health care. Commonly, morbidity is not only physical but also psychological. In individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), between 10–57% have co-morbid depression and between 7–50% have co-morbid anxiety1. Research demonstrates how psychological interventions, commonly based on cognitive behaviour (CBT) models, can improve anxiety and depression in COPD2, albeit with appeals for more robust research studies to improve this evidence base3.

Healthcare professionals are increasingly being encouraged to incorporate more advanced psychological skills in their clinical care. This is partly driven by limited access or long waiting lists for existing psychological services4 but also patient level barriers in attending psychological services, such as accommodating further appointments into demanding treatment schedules, mobility limitations and unexpected illness exacerbations5. People with COPD have a disproportionately lower attendance rate at Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (now known as Talking Therapies) services and poorer outcomes compared with other long-term conditions6.

Some patients might also prefer receiving condition-related psychological support from their trusted physical healthcare professional, and stakeholders (healthcare professionals and commissioners) providing COPD services have confidence that respiratory healthcare professionals can provide psychological support with the appropriate training and support7. However, whilst this approach is intuitively appealing, supporting patients with psychological interventions often requires adjustments to traditional clinical consultation styles. The healthcare professional’s role as problem solver changes to one where the patient is the expert in their illness experience, who needs support and guidance to achieving their goals but not necessarily advice or instruction.

Training is recognised and understood as essential for the delivery of these approaches, however it is important to go further and assess competency of delivery in clinical practice. This assessment of whether an intervention is delivered as planned is termed fidelity and is central to our understanding of whether respiratory nursing or other allied healthcare professionals can successfully implement cognitive behavioural approaches in practice. Importantly, fidelity of intervention delivery should be assessed both in the early stages post training and after a period of delivery as previous literature has reported examples of therapeutic drift or learning effects8.

The current study examined whether respiratory healthcare professionals could deliver a cognitive behavioural intervention with fidelity and explore which features were delivered with higher or lower competence. The context for this research question was the TANDEM (Tailored intervention for Anxiety and Depression Management in COPD) trial in which a complex, tailored, psychological intervention for people with COPD was delivered by specially trained and supervised facilitators (respiratory nurses, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists)9,10. This was recently evaluated in a pragmatic PHASE III trial (ISRCTN59537391), the largest randomised controlled trial of its kind in COPD. The trial results showed that the intervention did not improve mild to moderate anxiety, depression, or quality of life in people with moderate to very severe COPD compared with controls at six- and 12-month follow-up11. However, whether this was a result of poor fidelity of delivery, or other factors remains a critical question both for interpretation of trial results and understanding of whether respiratory healthcare professionals can be trained in these approaches.

As part of the process evaluation within the TANDEM study12, we aimed to evaluate the TANDEM intervention fidelity. We developed a fidelity evaluation that was feasible to conduct within the context of a randomised controlled trial including a bespoke treatment fidelity evaluation framework and facilitator therapeutic competency assessment. We assessed audio-recorded TANDEM treatment sessions for evidence of treatment delivery and therapeutic competence.

Methods

TANDEM intervention and trial

The TANDEM intervention was designed to be delivered by respiratory healthcare professionals (nurses, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists) to individuals with moderate to very severe COPD (FEV1 < 79% predicted13) and mild to moderate anxiety and/or depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression scores ≥8 to ≤15 for one or both conditions14). Trial participant details and inclusion criteria are reported in the main trial papers10,11. Trial participants received between six and eight, one-to-one sessions, appropriately tailored for their requirements (Table 1). The minimal dose of the intervention was pre-determined as two sessions (Sessions 1 and 2). One additional refresher session was allowed in situations where an intervention participant had to pause receipt due to ill health or other reasons.

As a tailored intervention, certain content could be omitted if deemed unnecessary. The role of the facilitators was to determine, in collaboration with the patient, the most appropriate tailored content. This decision was guided by the completion of the PHQ9 and GAD7 scales during the first session, allowing facilitators to focus on specific needs, such as prioritising depression over anxiety (or vice versa) based on the patient’s presentation. Core content across sessions comprised: agenda setting, home practice, feedback on home practice, depression (PHQ9) and anxiety (GAD7) measures; the cognitive behaviour formulation explained interpretation of COPD symptoms, behaviour, thoughts and problems and underpinned any intervention content. Cognitive behavioural formulation explains how thoughts, feelings, physical sensations and behaviour are interconnected, and unhelpful thoughts and behaviour can trap people in a negative cycle which affects how they experience and manage their condition.

TANDEM sessions took place in participants’ own homes or in a local health care setting (e.g., community respiratory clinic, primary care clinic), according to participant preference. Each session lasted between 40 and 60 min, and participants were encouraged to complete home practice tasks between sessions. Content was informed by self-management and cognitive behavioural approaches and has been described in full previously9.

TANDEM facilitators received a bespoke, interactive three-day cognitive behavioural based training course with between-session practice. All facilitators were provided with a manual and resources to support delivery such as crib cards, handouts, and participant resources. Facilitators completed competency assessment through video-based role play with a simulated patient actor, prior to approval as TANDEM facilitators15 and received fortnightly supervision throughout the trial. The TANDEM trial recruited 423 participants with COPD (n = 242 randomised to intervention arm) from primary, community, and secondary care services across 12 geographical regions in England, UK during June 2018 to March 2020. Full details of the trial and outcomes are reported elsewhere9,10,11.

Intervention fidelity measures

In line with Carrol’s definition of fidelity we considered it important to assess both adherence to and competence of facilitator delivery16.

Adherence to TANDEM intervention core components

The fidelity framework (Supplementary file reproduced with permission15) was created to reflect the intervention content and structure (Table 1) incorporating whether core tasks were delivered on a three-point scale (1 = not delivered, 2 = partial delivery and 3 = optimal delivery). Topic specific content was coded as delivered (1 = Yes) or not delivered (0 = No) with notes/examples to support assessment. Due to tailoring, there was variability in the items expected to be delivered and this was accounted for in scoring. A full description of the development of the fidelity framework is available15. An independent assessor (VW), blind both to facilitator and participant identification and trial outcome measures, partnered the TANDEM intervention development team to create the bespoke framework.

Cognitive First Aid Rating Scale to assess therapeutic competence

The therapeutic competence of facilitators was rated using the Cognitive First Aid Rating Scale (CFARs)17. The validated 10-item CFARs scale (Cronbach’s Alpha 0.93) is an adapted version of Blackburn’s revised Cognitive Rating Scale, adjusted to measure the skills and competencies of newly trained “CBT-naïve” healthcare professionals, and appropriate for those supporting patients with their physical, as well as psychological, symptoms18. Each item (details reported in Table 2) is scored from zero (poor skills and competency) to six (high level of skill and competency). This scale is recommended for completion for each session within a therapy series and an average rating can be calculated for all therapy sessions for an individual (i.e. participant cases). A total score of >30 and three or above on any item is considered to reflect therapeutic competence.

Sampling of audio-recorded treatment sessions

Treatment sessions delivered by facilitators were audio-recorded. A participant ‘case’ was defined as a series of sessions delivered to that participant. Whilst the intervention content was structured in recommended sessions, the order could vary due to the variability of participant needs. It was therefore important to include all sessions for each participant in the fidelity assessment. We aimed to code the fidelity of a random 10% sample of participant cases. To ensure all facilitators were represented in the sample, randomisation was conducted within each facilitator’s caseload. The TANDEM trial manager (RS), independent of the fidelity assessors, conducted the randomisation (using random number sequencing). To assess potential learning effects or therapeutic drift, cases were selected from the beginning and end of each facilitator’s case load. For facilitators who delivered the intervention to nine or fewer participants, one full case was randomly selected from their first five cases. For facilitators who delivered to ten or more participants, two full cases were included, one from the first five cases and one from their 10th to 15th cases.

Assessment of TANDEM treatment sessions

Coding was conducted by a psychologist (VW), trained in psychological interventions and cognitive behavioural methods more generally. Key sessions (i.e. those where core content was delivered) were selected from seven cases (19.4%) and were second coded by a member of the study team (LS) for quality assurance, however, to ensure consistency the scores of the primary coder were those used for analysis. The fidelity assessment procedure was piloted by VW, LS, and ST, using a randomly selected sample of audio-recorded treatment sessions, which were not included in the primary fidelity assessment sample.

Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software (version 17). Mean scores were calculated for continuous data reflecting overall and item-specific scores on the therapeutic competency CFARS. To explore potential learning effects or therapeutic drift, we examined CFARs change scores from early to late cases for facilitators (n = 9) who had two cases assessed for fidelity. High treatment adherence was defined as observing completed delivery of at least 80% of TANDEM content items for each session.

Funding and ethics

This study is independent research, funded by the National Institute for Health and Social Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme (project number 13/146/02). TANDEM trial registration: ISRCTN Registry 59537391. Registration date 20 March 2017. ST and VW were supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) North Thames. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Ethical approval was granted by the London-Queen Square Research Ethics Committee, reference 17/LO/0095. Written informed consent to audio-record and analyse TANDEM treatment sessions was provided by participants prior to data collection. All audio files were named with anonymous codes to ensure that the facilitator and participant identification were concealed. The audio files and anonymised transcripts were password protected and saved digitally on encrypted data storage.

Results

Fidelity sample

The recruitment and assessment of facilitators has been reported previously15. A total of 31 trained facilitators were deemed competent to deliver the intervention and approved to proceed with the trial. However, for practical reasons unrelated to the trial, three facilitators did not deliver any sessions, leaving 28 facilitators to implement the intervention. The facilitator group included clinical professionals from respiratory nursing (n = 8), respiratory physiotherapy (n = 14), and occupational therapy (n = 6). All were degree-educated and employed within the UK National Health Service at the following levels: Senior/Specialist Band 6 (n = 6), Advanced/Management Band 7 (n = 17), and Senior Management/Clinical Lead Band 8 (n = 5).

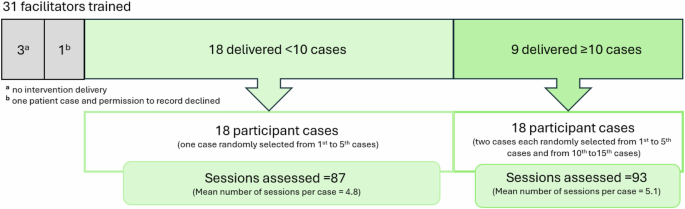

Of the 28 facilitators who did deliver TANDEM, one delivered to only one participant who did not consent to audio-recording. A total of 27 facilitators were therefore assessed for their fidelity in delivering the intervention. 18 facilitators delivered to fewer than ten participants and thus each had one complete case assessed. Nine facilitators had two cases assessed as they delivered TANDEM to more than ten participants. This resulted in a total of 36 participant cases with a total of 180 treatment sessions randomised for assessment, representing 15% of the total number (n = 242) of intervention participants (Fig. 1). Audio data for 16/180 (9% of the fidelity sample) treatment sessions were missing/inaudible for technical reasons but trial case report forms were available to confirm core content.

Schema of facilitators trained, number of participant cases selected, and sessions analysed.

Intervention delivery

In the trial, 242 participants were randomised to receive the TANDEM intervention, with over half (56%) receiving ≥ six sessions, 24 (10%) only had one session and 22 (9%) did not receive any treatment. 196 (81%) participants received the pre-defined minimum dose of two intervention sessions. In the fidelity sample, the median number of audio sessions per case was five (IQR = 2) and 16 participants (44% of the fidelity sample) received ≥ six sessions. Three participants (8% of the fidelity sample) received just one session, so 33 (92%) trial participants in the fidelity sample received the minimum intervention dose.

Adherence to TANDEM intervention core components

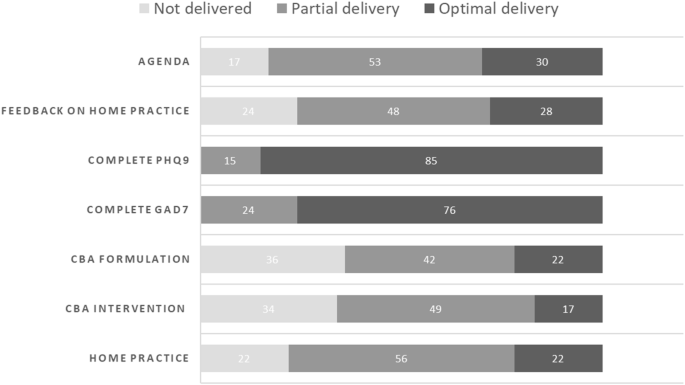

Core intervention components which were expected to be delivered at some point in the therapy series are illustrated in Fig. 2. Facilitators showed fidelity in consistently setting an agenda during sessions; however, in only 30% of cases did both the facilitator and the patient contribute to the agenda. Assessing patients for symptoms of depression (PHQ9) and anxiety (GAD7) was delivered optimally in 85 and 76% of cases, providing outcomes and feedback of the assessments to the patient. Referring (explicitly or implicitly) to the cognitive behaviour formulation was delivered in all except four cases overall but delivery was inconsistent across sessions. Patients received home practice instructions as part of their intervention and in 78% of cases, this was delivered with fidelity across sessions, but did not always reach optimal delivery where a clear demonstration and comprehension check was carried out.

Core intervention components adherence (%).

Intervention content delivered

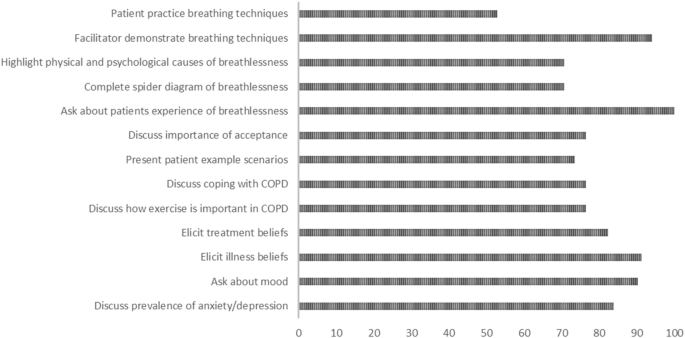

In sessions one and two, there was high adherence to the intervention protocol with the topics required for minimal dose of treatment; eliciting illness (91.2%) and treatment (82.4%) beliefs and introducing mood content (90.3%) included in most cases. All participants were asked about their experiences of breathlessness (Fig. 3). Facilitators demonstrated breathing techniques in nearly all cases but only half of participants were heard practicing the techniques back to the facilitator.

Minimal sessions dose content: topics delivered (%).

Session content varied from session three onwards depending on participants’ needs. Anxiety intervention content was delivered to 25 (69%) of the 36 participants and depression intervention content was delivered to 21 (58%) participants; 14 (39%) of participants received both anxiety and depression content. Four participants received no specific anxiety or depression content as treatment did not continue past session two. Optional problem-solving skills intervention content included exploring daily living with COPD, identifying problems experienced and developing problem solving skills. 20 (56%) participants’ treatment ended before problem solving intervention content was delivered. Of the 16 participants who received these sessions, 12 (75%) identified and worked through a problem-solving example; eight (50%) included problem based coping style and six (38%) received goal setting support. A final session introduced pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) to participants and was expected to be delivered to all unless participants confirmed previous PR attendance. 23/36 (64%) participants confirmed their future intention to attend PR. Discussing what to expect from PR was delivered in 20 of these cases (87%) as was eliciting attitudes to PR: thoughts, feelings, and expectations about PR (22 cases, 96%). The photobook (a bespoke book of photographs to enable facilitators to familiarise participants with their local PR services and staff using visual methods) was only used in five cases.

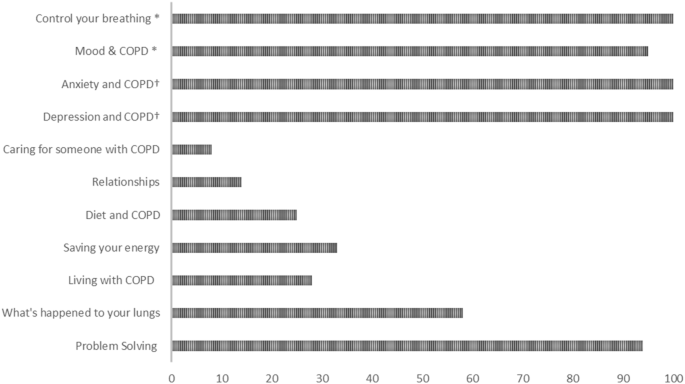

Intervention content handouts were provided by facilitators for participants to review between sessions (Fig. 4). All participants (36) received the core Control your Breathing handout and all, except two, received the core Mood & COPD handout. All participants who received Anxiety and Depression intervention content, received the accompanying handout. Of the 16 participants who received problem-solving intervention content, 94% received the accompanying handout. Remaining handouts were provided to participants (or their carers) as required.

*Core handouts † Handouts based on those participants who received anxiety and depression content.

Cognitive First Aid Rating Scale to assess therapeutic competence

Overall, the mean facilitator therapeutic competence (CFARs) total score was 35.5 (SD = 7.0). Fidelity (mean score of ≥ 30) was achieved in 28 (78%) out of 36 cases. Scale item means are reported in Table 1. Higher competency was observed for focus & structure of the session, collaborative relationship, and interpersonal effectiveness. In contrast, facilitators demonstrated lower competency for guided discovery and application of appropriate change techniques, however, all components are rated above the therapeutic threshold of three.

Therapeutic competence – change over time

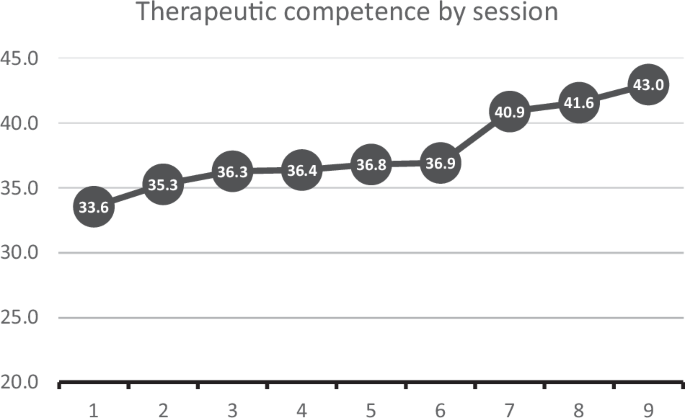

For facilitators with two cases (n = 9), mean therapeutic competence for early cases (comprising 45 sessions) was 32.3 (SD = 6.8), which increased to 37.6 (SD = 7.4) in later (comprising 41 sessions) cases (MD = 5.4, p = 0.13). There was a trend towards higher therapeutic competency as sessions progressed from 1–9; session 1 scores had a mean 33.6 (SD = 7.2) and means in the later sessions (7–9) ranged upwards from 40.9 (SD = 9.1) but the sample of later sessions was small (Fig. 5). There was no association between the number of sessions delivered to each participant and Facilitator therapeutic competence (r = 0.18, p = 0.3) suggesting other factors affected the number of sessions delivered.

Cognitive First Aid Rating Scale by session number.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to conduct an evaluation of the TANDEM intervention fidelity; to assess how well the intervention was implemented according to its intended protocol. We developed a fidelity evaluation that was feasible to conduct within the context of a randomised controlled trial including a bespoke treatment fidelity evaluation framework and a validated therapeutic competency assessment15. Overall, the evaluation suggests that with proper training, guidance, and supervision, respiratory nurses and other respiratory healthcare professionals can deliver cognitive-behavioural interventions with acceptable therapeutic competency, but further training would be needed to optimise intervention delivery.

Trial facilitators adhered well to the intervention protocol, and core components were delivered with fidelity with one exception – Sets agenda for the session. In cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), agenda setting is a collaborative process where patient and therapist agree how their session time will be spent. It highlights what is most important for the patient19 and is considered an important task for enhancing therapeutic alliance, an independent predictor of patient outcomes20. It may have been that in order to adhere to session content facilitators were reluctant to invite a patient agenda for fear of being side tracked. It might also reflect the learned clinical practice influenced by data driven templates which encourage a check-list consultation style and prioritises the healthcare professional’s consultation agenda over the patient’s21. Supporting the skill development of shared agenda setting might need more focus and on reflection, the TANDEM training programme could have addressed this task with greater emphasis, and this is noted as an important focus for future training.

Content that was delivered with high fidelity included establishing illness and treatment beliefs, breathlessness experiences and mood, which were important early activities to inform the intervention tailoring. In a separate interview study, facilitators described their increased confidence in asking participants about their beliefs and mood after training, reflecting that this was a something they might have previously avoided in clinical practice22. Facilitators asked all participants about their breathlessness and demonstrated breathing techniques with very high fidelity, yet only about half the participants were heard practicing these skills in the session. Demonstration and repetition of behaviour by a recipient are important behaviour change techniques, particularly when learning a new skill23 such a specific breathing techniques in COPD. Healthcare professionals may not frequently encourage or prompt these actions from their patients; It is not clear why this is, perhaps this relates to the point previously made about the challenges of shared agenda setting. The facilitators may have been more familiar with instructing and demonstrating the techniques but less accustomed to inviting patients to demonstrate their skills. This suggests a valuable focus for future interventions to enhance facilitator training. Encouraging these techniques more consistently could enhance the effectiveness of embedding new skills.

The therapeutic competency scores of facilitators in this study is comparable with previous research studies including palliative care nurse practitioners, newly trained in cognitive behavioural methods, assessed during month six of a trial with cancer patients17 and clinical nurse specialists (assessed using simulated patient role play after two years’ patient delivery24). In a COPD trial similar to TANDEM, respiratory nurses’ mean therapeutic competence, was rated considerably higher (44.0)25; however in that trial, two of the four nurses had completed a post-graduate diploma in CBT, so could not be considered as novice.

For specific therapeutic skills, we found higher competency for focus, pacing, collaborative relationship and interpersonal effectiveness, which likely represents the existing well-honed skills that healthcare professionals possess26. It appeared to be more challenging to reach competency in specific CBT skills such as guided discovery and eliciting key components of the model, however, higher competency was observed over time in the TANDEM trial. Evaluating both ‘early’ and ‘late’ cases, there appeared to be a trend towards higher therapeutic competency overall in the later cases which might suggest that these skills improve over time (though this observation is limited to the nine facilitators who delivered more than ten cases). Improving therapeutic competency over time has been well-documented, with evidence suggesting that experience, particularly when combined with supervision, is associated with significant improvements in CBT competence17. However, our findings should be interpreted cautiously as case numbers were limited. Therapeutic competence also appeared to strengthen ‘within cases’, as the sessions progressed, from therapeutic competency scores of 33.6 on average for Session 1 to scores >40 for Sessions 7–9, although as there were fewer later sessions to assess, this finding again needs further evidence from larger samples.

This study has many strengths including the comprehensive development of a bespoke framework, the result of a systematic collaborative process with both trial and independent researchers, to pilot, evaluate and refine the framework to ensure its optimum suitability. Recognising the complexity of tailored interventions, we made the decision to assess all audio sessions within each randomised case to ensure that content could be coded regardless of the session in which it was provided. This resulted in a substantial caseload (coding approximately 180 h of audio sessions) which required resources in addition to the trial funding (supported by the NIHR ARC North Thames). Facilitator-completed case report forms were also consulted to support the adherence analysis. This proved valuable for confirming intervention delivery details, such as identifying the leaflet provided when it was not mentioned in the audio or when audio recordings were unavailable.

Assessing fidelity through audio recordings is a robust method, representing the gold standard approach encouraged in the National Institutes of Health Behaviour Change Consortium (NIH-BCC) Framework27 and necessary to examine therapeutic competence, but is not without limitations. For sessions delivered at home, audio recordings were sometimes unclear due to background noise, interruptions from family members, or patients discussing other complex physical and social issues important to them. This challenge has been noted previously24 and was also highlighted in the patient and facilitator qualitative studies22. To address these challenges and assess this novel intervention, we complemented our bespoke framework with established methods recommended in recent fidelity literature8 Specifically, we measured therapeutic competence using the validated CFAR scale17. Employing existing measures ensures adherence to known standards and facilitates comparisons with other trials.

The fidelity assessment was completed by VW, independent of the trial intervention development, trial processes and facilitator supervision. LS provided quality assurance assessments and met regularly with VW to discuss cases and resolve any queries. However, we were unable to undertake full duplicate coding due to the lack of resources for the time-consuming task; we acknowledge this is a limitation of our study. Calls are made to ensure that sufficient resources are included for fidelity in the same way as other trial assessments such as health economics and the research community needs to agree of the importance of this task. We also recognise that, by including all sessions within each case (up to 9 per case), the number of cases is fewer that we would have ideally included (15% of the intervention group where ideally, we would have included 20%). However, due to the variability of a tailored intervention, it was not feasible to only assess certain sessions within cases.

Implications for clinical care

Respiratory healthcare professionals can be trained to deliver interventions underpinned by psychological approaches. This is important given the increasing demand for psychological support particularly amongst those with long term co-morbid conditions and the challenges in obtaining support from psychological services. However, resource constraints may also hinder respiratory healthcare professionals from incorporating psychological support into their clinical care, if it takes, or is perceived to take, additional time. It is also important to highlight the training and support needed to enable clinicians to take on this role. Firstly, it is important that there is a robust training programme where people are assessed in competency before they practice. In this trial we found that, despite pre-training interviews, some individuals were not suitable to deliver the intervention even after repeat training and there should not be an assumption that this approach is suitable for all. At interview, potential facilitators for the TANDEM trial had to demonstrate a commitment to a biopsychosocial approach to treatment, which emphasises holistic, patient-centred care, ensuring that both emotional and social contexts are integrated into the therapeutic process. In clinical practice, attention should be given to healthcare professionals’ communication skills and their experience, training and continued interest in psychological approaches to care. Secondly, supervision is essential to provide support for clinicians and to ensure quality of clinical care. Although not formally evaluated in this study, qualitative findings suggested that facilitators perceived supervision as essential and its place in such care is well established22. Finally, in the trial, Facilitators were provided with a comprehensive intervention manual outlining session content, example skills delivery and background theory as well as resources to use in sessions such as prompt cards. It is likely that when using such techniques in a busy clinical service these approaches will be even more important.

Conclusion

We completed a comprehensive fidelity evaluation of a cognitive behavioural informed intervention for people with COPD. Overall, TANDEM treatment sessions were delivered as per protocol and most, but not all, components were delivered with high fidelity. Greater attention should be paid to training and supporting healthcare professionals’ skills in shared agenda setting. Therapeutic competency was observed overall but results suggest a need to improve core CBT skills (e.g. guided discovery). Conducting comprehensive fidelity assessments is an important part of developing and evaluating interventions. They enable researchers to reliably assess intervention delivery and receipt, to refine intervention content and training, and overall, to enhance and optimise implementation of successful interventions.

Responses