Association and shared biological bases between birth weight and cortical structure

Introduction

According to Barker’s hypothesis [1], it is established that intrauterine growth plays a crucial role in shaping various neuropsychiatric traits, such as intelligence and cognitive outcomes, which extend beyond childhood into young adulthood and midlife [2,3,4]. This insight has spurred studies exploring the structural variations in the brain associated with birth weight as a proxy for intrauterine growth [5, 6]. For instance, two cohort studies have identified associations between birth weight and two cortical structural phenotypes, including cortical volume and surface area [7, 8]. However, despite these findings, the current evidence on the association between birth weight and cortical structure remains incomprehensive, leaving several gaps that warrant further investigation.

One essential gap is the lack of robust evidence regarding the relationship between birth weight and more complex aspects of cortical morphometry, such as the folding, curvature, and microstructural phenotypes, which are more reflective of myelination and cytoarchitecture [9]. For example, current evidence for the association between birth weight and fractional anisotropy was controversial. Rimol et al. suggested a significant association between very low birth weight and fractional anisotropy among 120 individuals [10]. However, this association was not consistently replicated across other studies [11, 12]. The inconsistency in reported findings likely stems from small sample sizes, as well as confounding biases and reverse causality inherent in observational studies [10,11,12]. Hence, further well-designed studies covering more complex aspects of cortical morphometry are essential to advancing the comprehensive understanding of the association between birth weight and cortical structure.

Another significant gap in the current literature concerns the mechanisms linking birth weight to cortical structure. One prevalent explanation suggests that adverse intrauterine conditions could elicit adaptive fetal responses that may have a long-term detrimental impact on brain development [2, 13, 14]. However, this explanation lacks a detailed understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved. To date, the biological pathways linking birth weight to cortical development remain largely unexplored. Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact biological underpinnings of these associations, thus facilitating the development of targeted therapies or preventive strategies to support optimal development of cerebral cortex.

Recent progress in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of cortical structure [15, 16], the development of genome-wide cross-trait analysis tools [17], and the publication of multi-omics datasets [18,19,20,21] have provided a new opportunity to address the abovementioned gaps. Researchers could examine the potential relationships between birth weight and cortical structure through two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analyses [22]. Furthermore, combining multi-omics datasets with genome-wide cross-trait analysis tools could enable the exploration of the shared biological relationships between birth weight and cortical structure, providing valuable insights into their potential mechanisms.

In this study, we aimed to address the abovementioned gaps by conducting a comprehensive analysis using a multi-omics framework to investigate both the association and biological relationship underlying birth weight and cortical structure. We first examined whether birth weight is associated with 13 aspects of global cortical structure measures. Then, for significant associations, we detected their shared causal genes across transcriptome and proteome to implicate the underlying mechanisms. At last, we identified the enriched cell types of birth weight to echo the previous analyses and explore the underlying pathways from a cellular perspective.

Materials and methods

Study overview

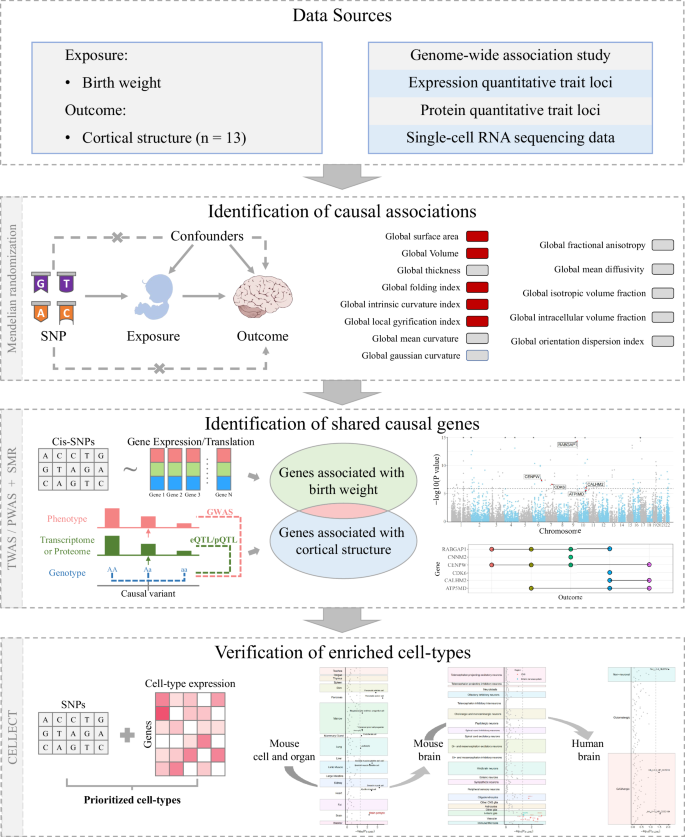

As depicted in Fig. 1, this study follows a three-phase approach. In phase 1, we conducted two-sample MR analyses to investigate the association of birth weight with cortical structure. In phase 2, we first performed a transcriptome-wide association analysis (TWAS) to identify gene expressions related to birth weight. Then, we carried out summary-based MR (SMR) analyses incorporating expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) datasets to determine whether these gene expressions could impact the cortical structure highlighted in the MR analyses. Additionally, we performed proteome-wide association studies (PWAS) and protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL)-based SMR analyses to provide evidence at the proteomic level. In phase 3, we applied the cell-type expression-specific integration for complex traits (CELLECT) method to explore the cell-type enrichment of birth weight. All data used in this study were deidentified publicly available data, therefore no ethical approval was required for this study.

CELLECT cell-type expression-specific integration for complex traits, eQTL expression quantitative trait loci, pQTL protein quantitative trait loci, PWAS proteome-wide association study, TWAS transcriptome-wide association study, SMR summary-based Mendelian randomization analysis, SNP single nucleotide polymorphism.

Data sources

Birth weight

We obtained the hitherto largest GWAS summary statistics of birth weight from the UK Biobank (UKB) and 35 studies participating in the Early Growth Genetics (EGG) Consortium [23] (Supplementary Table 1). In the original GWAS, up to 321 223 participants of predominantly European ancestry (~ 93%) were recruited. Birth weight was collected through actual measurements, medical records and self-reporting. All birth weight measures were transformed to z-score before analysis. A fixed-effects meta-analysis was conducted to combine the summary statistics from the UKB and the EGG Consortium. After approximate conditional and joint multiple SNP analyses, 146 independent SNPs reaching a significant threshold of 6.6 × 10−9 were reported [23]. We selected 143 independent significant SNPs located on autosomes as instrumental variables (IVs) for birth weight in the two-sample MR analysis (Supplementary Table 2). We also downloaded summary statistics consisting of 298 142 individuals of European ancestry for other downstream analyses.

Global cortical structure

We obtained the hitherto latest and the most comprehensive GWAS summary statistics of cortical structure involving 36 663 individuals from the UKB and the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study [15] (Supplementary Table 1). Thirteen aspects of cortical phenotypes were analyzed globally and regionally in the original GWAS. High-resolution anatomical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data were processed to extract 8 cortical macrostructural phenotypes, including surface area (SA), volume, thickness, folding index (FI), intrinsic curvature index (ICI), local gyrification index (LGI), mean curvature (MC) and gaussian curvature (GC). Diffusion MRI data were processed to extract 5 cortical microstructural phenotypes, including fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), isotropic volume fraction (ISOVF), intracellular volume fraction (ICVF) and orientation diffusion index (ODI). Before analysis, all cortical phenotypes were standardized, and the global measures were calculated as the average across the 180 bilaterally averaged cortical regions. We obtained the full-set summary statistics of global measures of the thirteen macro- or microstructural phenotypes for analysis.

Statistical analysis

MR

We performed two-sample MR analyses to investigate the association between birth weight and cortical structure [22]. Initially, we computed the R2 to determine the variance in birth weight explained by the IVs and used F-statistics to assess the strength of the IVs. IVs with F-statistics below 10 were considered weak instruments and excluded from analysis.

For the primary analysis, we employed the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) approach [22], operating under the assumption that all genetic variants are valid IVs. We complement the IVW MR with the weighted median, MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO and IVW radial methods. The weighted median method can robustly estimate the causal relationship even when less than 50% of the genetic variants are invalid IVs [24]. MR-Egger method includes an intercept term to account for directional pleiotropy [25]. The MR-PRESSO method could detect outliers and refine causal estimates by removing these outliers [26]. The IVW radial method allows more straightforward detection of outliers and influential data points [27]. We also performed leave-one-out analyses to identify if any SNP disproportionately drove the associations. To investigate potential bias due to sample overlap between birth weight and cortical structure, we further conducted the MRlap method [28]. Furthermore, considering educational attainment and adult body mass index as potential confounders (Supplementary Materials) [8, 29], we implemented Multivariable MR (MVMR) analyses [30] to evaluate the independent effect of birth weight on cortical structure.

We used Bonferroni correction to account for multiple tests in the primary analyses. An association was considered significant if the P-value in the primary analysis was below 3.846 × 10−3 (0.05/13) and the direction of effect estimates remained consistent across all methods. We reported the MR analyses following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology using MR (STROBE-MR) [31] (Supplementary Table 4).

TWAS

We performed a primary TWAS following the FUSION pipeline [32] to identify gene expressions associated with birth weight. We integrated birth weight summary statistics with a cross-tissue expression weight calculated through sparse canonical correlation analysis (sCCA) [19]. A total of 37 917 sCCA features extracted from the GTEx v8 release were involved in the cross-tissue expression reference weights. We defined significant results at P < 1.319 × 10−6 (0.05/37 917) using Bonferroni correction based on the number of features tested across the reference weights. As a sensitivity analysis, we performed S-MultiXcan analysis [33] for birth weight based on expression data from 49 tissues in GTEx v8 release to examine the robustness of the sCCA-TWAS results (Supplementary Materials).

PWAS

We performed PWAS following the FUSION pipeline [32, 34] to identify proteins associated with birth weight. We used a reference weight developed based on protein abundance measures of 376 dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dPFC) samples from the Religious Order Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project (ROS/MAP) [18]. A total of 1 761 proteins were tested in the proteome reference weight. We defined significant results at P < 2.839 × 10−5 (0.05/1 761) using Bonferroni correction based on the number of proteins tested across the reference weight.

SMR

We implemented the SMR & HEIDI methods to prioritize gene expressions and proteins that could impact cortical structure [35]. The eQTL summary data were obtained from the BrainMeta dataset, which includes RNA-seq data from 2 865 brain cortex samples of 2 443 unrelated individuals of European ancestry [21]. The pQTL summary data were sourced from the ROS/MAP, which contains protein abundance measures from 1 277 dPFC samples of European ancestry [20]. Bonferroni correction was applied to consider multiple comparisons. Significant gene expressions and proteins were confirmed if the adjusted P-value for SMR analysis < 0.05, with a conservative unadjusted P-value for Heterogeneity in Dependent Instrument (HEIDI) test > 0.01.

CELLECT

To identify cell types related to birth weight, we performed CELLECT analyses with default parameters [36]. GWAS summary statistics of birth weight with three sources of cell-type expression were used in the analyses. Firstly, we used the Tabula Muris dataset, which contains 115 cell types from 18 mouse organs, of which 7 cell types are related to brain [37]. Then, we used the Mouse Nervous System dataset, which includes 265 cell types from the mouse nervous system [38]. Finally, due to the relatively significant differences between mice and humans, we incorporated the Allen Brain Map Human Multiple Cortical Areas SMART-sequence dataset, which investigates 120 cell types from the human cortex [39]. Significant results were identified with a nominal unadjusted P-value < 0.05.

Results

Association between birth weight and cortical structure

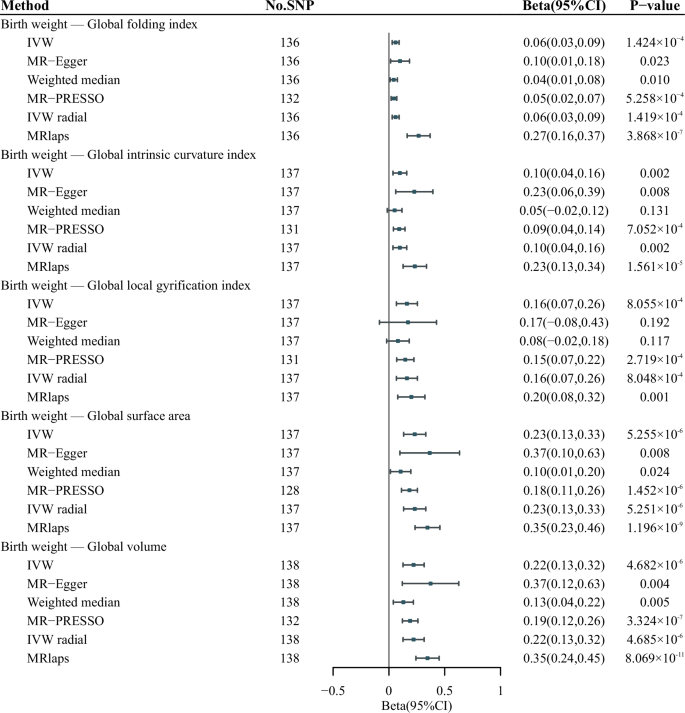

The F-statistics for all IVs were greater than 10, indicating enough statistical power for the instrument (Supplementary Table 2). Our IVW results indicated that genetically predicted birth weight was positively associated with five cortical macrostructural phenotypes, including global FI (β, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.03–0.09), ICI (β, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.04–0.16), LGI (β, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.07–0.26), SA (β, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.13–0.33) and volume (β, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.13–0.32), after Bonferroni correction (Fig. 2). The association between genetically predicted birth weight and global GC reached nominal significance (β, −0.05; 95% CI, −0.09 to −0.01, P = 0.0197). No association was found between birth weight and global microstructural phenotypes (P > 3.846 × 10−3). For the significant associations, concordant estimates were suggested by weighted median, MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO and IVW radial methods. MRlap method also indicated consistent findings, suggesting the results were robust to sample overlap (Supplementary Table 3). Leave-one-out analyses showed no outlying SNPs (Supplementary Fig. 1). Further adjustments for educational attainment and adult body mass index yielded directionally consistent results, with global SA and volume remaining significant, while FI, ICI and LGI reached nominal significance (Supplementary Table 5).

Only significant results are presented. Results of the IVW method were corrected using the Bonferroni correction with P < 3.846 × 10−3 indicating statistical significance. IVW inverse-variance weighted.

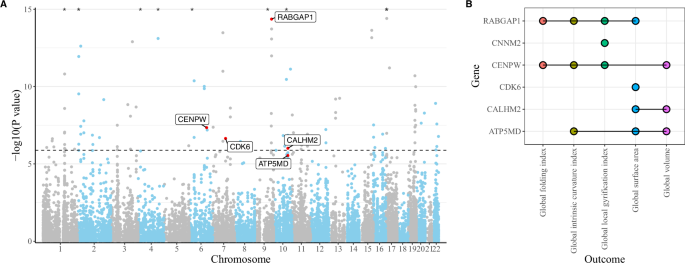

Gene expressions linking birth weight and cortical structure

The sCCA-TWAS identified 223 gene expressions associated with birth weight (P < 1.319 × 10−6) (Supplementary Table 6–9), of which 143 were included in the eQTL dataset for subsequent SMR analyses. Among these, six gene expressions (RABGAP1, CNNM2, CENPW, CDK6, CALHM2 and ATP5MD) were also associated with at least one cortical structural phenotype (P < 3.497 × 10−4) (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 10–15). Sensitivity analysis with S-MultiXcan showed 337 gene expressions associated with birth weight (P < 2.259 × 10−6), with 192 included in the eQTL dataset. Of these, five gene expressions (RABGAP1, CNNM2, CENPW, COMMD7 and DNMT3B) were associated with at least one of the cortical structural phenotypes (P < 2.604 × 10−4; Supplementary Table 16–22).

A Results of sCCA-TWAS using the top sCCA feature (sCCA1). Bonferroni correction was utilized to consider the multiple tests. The horizontal dashed line indicates the significance threshold of P < 1.319 × 10−6 (0.05/37 917). Gene expressions that were also associated with cortical structure have been labeled. CNNM2 was identified by sCCA-TWAS using sCCA2 feature therefore not labeled here, see Supplementary Table 7. Points with P-values less than 1 × 10−5 are marked with asterisks. B Overlapping gene expressions between sCCA-TWAS and eQTL-based SMR analyses. Bonferroni correction was utilized to consider the multiple tests. eQTL expression quantitative trait loci, TWAS transcriptome-wide association study, sCCA sparse canonical correlation analysis, SMR summary-based Mendelian randomization analysis.

In the primary and sensitivity analyses, three gene expressions (RABGAP1, CENPW and CNNM2) were consistently identified (Fig. 3). RABGAP1 was associated with global FI, ICI, LGI and SA. CENPW was related to global FI, ICI, LGI and volume, but not SA. CNNM2 was associated with global LGI. ATP5MD, CDK6 and CALHM2 were not identified in the sensitivity analyses.

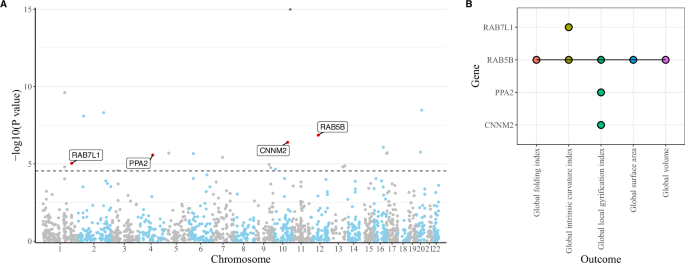

Proteins linking birth weight and cortical structure

The PWAS identified 24 cis-regulated proteins in the dPFC associated with birth weight (P < 2.839 × 10−5), including 16 novel signals compared to the sCCA-TWAS (Supplementary Table 23). Among these, 23 were included in the pQTL dataset. Subsequent SMR analyses revealed that four cis-regulated proteins (RAB7L1, RAB5B, PPA2 and CNNM2) were also related to at least one cortical structure (P < 2.174 × 10−3) (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 24–29). The cis-regulated protein of CNNM2 was identified as linking birth weight and global LGI, which is consistent with the transcriptomic findings. Additionally, we found that the cis-regulated protein of RAB5B was related to multiple cortical structures, including global FI, ICI, LGI, SA and volume. The cis-regulated proteins of RAB7L1 and PPA2 were also associated with global ICI and LGI, respectively.

A Results of PWAS for birth weight. Bonferroni correction was utilized to consider the multiple tests. The horizontal dashed line indicates the significance threshold of P < 2.839 × 10−5 (0.05/1 761). Proteins that were also associated with cortical structure have been labeled. Points with P-values less than 1 × 10−5 are marked with asterisks. B Overlapping proteins between PWAS and pQTL-based SMR analyses. Bonferroni correction was utilized to consider the multiple tests. pQTL protein quantitative trait loci, PWAS proteome-wide association study, SMR summary-based Mendelian randomization analysis.

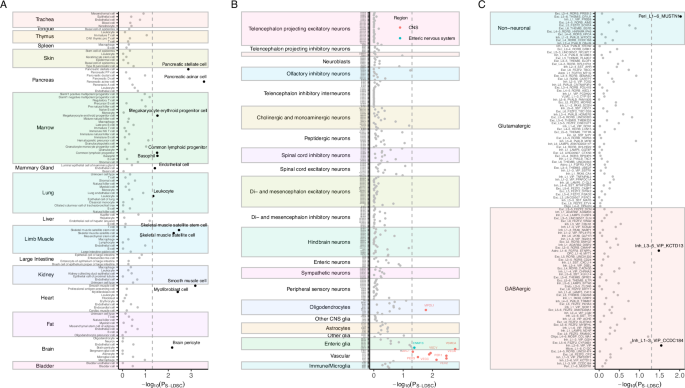

Birth weight variants enriched in cell types of mouse and human brain

For the Tabula Muris dataset, we identified significant enrichment in brain pericyte (P < 0.05). In addition, applying analyses to the Mouse Nervous System dataset, we identified 10 enriched brain cell types associated with birth weight, predominantly annotated as vascular cell types and located within the central nervous system (CNS) (P < 0.05). In the human cortex dataset, we found three cell types significantly associated with birth weight, two of which were inhibitory GABAergic neurons and the other was a non-neural cell type annotated as pericyte (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 30–32).

A Cell type enrichment of birth weight using the Tabula Muris dataset. B Cell type enrichment of birth weight using the Mouse Nervous System dataset. C Cell type enrichment of birth weight using the Allen Brain Map Human Multiple Cortical Areas SMART-sequence dataset. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the nominal significance threshold of P < 0.05. CELLECT cell-type expression-specific integration for complex traits, CNS central nervous system, LDSC linkage disequilibrium score regression.

Discussion

This study thoroughly investigated the potential phenotypic associations and biological relationships between birth weight and various aspects of cortical structure. It indicated positive associations between birth weight and several cortical macrostructural phenotypes, including global FI, ICI, LGI, SA and volume. Additionally, we suggested potential biological relationships underlying these associations, pinpointing functional genes such as CNNM2, CENPW, RABGAP1, ATP5MD and RAB5B, whose cis-regulated expression or protein may participate in these associations. Brain cell types such as inhibitory neurons and pericytes were also implicated with birth weight, implying the cellular bases behind the observed associations. These findings highlighted the early determinants of birth weight on cortical anatomy and prioritized candidate pathways to be further studied, facilitating the discovery of therapeutic targets for precision interventions.

Although limited research on the association between birth weight and cortical structure, some studies are consistent with our findings on birth weight and cortical folding (FI, ICI and LGI), SA and volume [8, 40,41,42]. These results suggest an important role of the intrauterine environment in cerebral cortical expansion, as both sulci-gyral folding and SA are associated with constrained cortical growth [43, 44]. We found that birth weight was positively correlated with cortical SA but not thickness, aligning with another study [8]. This may be attributed to the different developmental mechanisms of SA and thickness, as the radial unit hypothesis suggests that cortical SA depends on the number of cortical columns, while thickness is determined by the number of neurons produced within those columns [45]. Additionally, considering the developmental sequence of cortical macrostructure and microstructure, it may be plausible that no association was found between birth weight and microstructure. The first six months after birth are critical for cortical microstructure growth [46, 47]. Similar evidence demonstrated that microstructural phenotypes of the cerebral cortex were associated with genes that had peak expression postnatally, rather than genes that were relatively highly expressed prior to birth [15].

Leveraging multi-omics approaches, we identified several functional genes, including CNNM2, CENPW, RABGAP1, ATP5MD and RAB5B, whose cis-regulated expression or protein levels may contribute to the biological mechanisms underlying the observed associations. Both the transcriptomic and proteomic analyses highlighted CNNM2, a gene encoding a magnesium transporter [48]. This finding aligns with existing literature. CNNM2 is located near a lead SNP (rs10883846) associated with birth weight [23], and it is also an important protein involved in brain development and neurological function [49]. Its expression in the prefrontal lobe was associated with sensorimotor gating function, dendritic spine morphogenesis, cognition and the risk of schizophrenia [50]. Several studies also provide insights into the mechanisms connecting CNNM2 and birth weight to cortical development. Birth weight has been associated with perinatal asphyxia [51] and brain maturation [52]. In an animal model of perinatal asphyxia, reduced CNNM2 expression was observed in asphyxia-induced rats [53]. Additionally, researchers have found that CNNM2 expression increased during neuronal differentiation, with higher levels in mature neurons compared to undifferentiated cells [53]. Taken together, these findings suggest that lower birth weight may reduce CNNM2 expression through mechanisms such as perinatal asphyxia or neuron maturation, potentially impacting cortical structure and brain function. Furthermore, our transcriptomic level analyses identified a significant signal located on the same chromosomal band of CNNM2 (10q24.33), namely ATP5MD. A study has demonstrated that knocking down CNNM2-rs1926032 could induce downregulation of ATP5MD expression, further disrupting the neurodevelopment [54]. These findings suggest additional pathways hinted by CNNM2 and ATP5MD, involving energy metabolism and magnesium transport [54], could be important biological mechanisms linking birth weight to cortical structure.

The expression of CENPW and RABGAP1 were replicated in the sCCA-TWAS and S-MultiXcan analysis for birth weight, and found to be associated with at least four target cortical structural phenotypes, serving as compelling evidence for important transcriptomic signals linking birth weight to cortical structure. CENPW encodes centromere protein W, which is crucial for chromosome maintenance and the cell cycle [55]. It is the nearest gene to rs6925689, a significant SNP associated with birth weight [23]. In this study, we observed that the CENPW expression was negatively associated with global FI, ICI, LGI and volume. Similar findings have also been found previously [15, 56, 57], supporting a role for CENPW in neurodevelopment. Evidence demonstrates that increased CENPW expression may lead to altered neurogenesis or decreased apoptosis, thereby affecting structural changes such as cortical expansion [57], which is also consistent with the radial unit hypothesis [45]. Regarding RABGAP1, it encodes a GTPase-activating protein involved in mitosis, cell migration, and vesicular trafficking. It is the nearest gene to another lead SNP (rs10985827) of birth weight [23], and related to a novel neurodevelopmental syndrome [58]. However, to our knowledge, the mechanisms by which CENPW and RABGAP1 are associated with birth weight or early development remain unclear, and more future studies are needed. Based on the biological functions of CENPW and RABGAP1, cell cycle regulation and intracellular transport might be crucial in the association between birth weight and cortical structure.

In our proteomic level analyses, we found the cis-regulated protein of RAB5B was associated with birth weight, global FI, ICI, LGI, SA and volume. RAB5B encodes a protein belonging to the Ras/Rab superfamily of small GTPases [59]. Previous studies have implicated Rab proteins in cortical neuron migration [60], neurodegeneration [61], cognitive function control [62], and etiopathogenesis of several neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson’s disease [63] and Alzheimer’s disease [64]. Nevertheless, RAB5B has not been widely recognized as associated with birth weight in the existing literature. The association between RAB5B and birth weight still warrants further investigation, and its role in the relationship between birth weight and cortical structure should be explored in future studies.

Our CELLECT analyses indicated that birth weight could be enriched in inhibitory neurons and pericytes in the human cortex. Previous study has shown that gestational age at birth was positively associated with gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentrations [65]. Similarly, another study also found that intrauterine growth restriction could affect GABAergic synapse development [66]. These findings support our results linking birth weight, a comprehensive proxy of intrauterine development, to inhibitory GABAergic neurons. Additionally, previous studies have identified that GABAergic neurons could play crucial roles in neurogenesis, migration, dendrite arborization and synaptogenesis during the mid-to-late gestation, which are related to cerebral anatomy including cortical expansion and sulcus formation [67,68,69]. As for pericyte, existing evidence has suggested that it was essential for blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity, a process that begins as early as the embryogenesis period [70]. BBB breakdown and brain capillary damage are early biomarkers of human cognitive dysfunction [71], and are linked to various neuropsychiatric disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease [72,73,74]. These findings align with our observations of cerebrovascular cell types in the mouse brain, despite the differences between the mouse and the human CNS. Given the evidence presented, further studies are warranted to elucidate the role of GABA and BBB underlying early life development and cortical structure.

Our findings have implications for understanding the intervention and mechanisms of neurodevelopment. First, birth weight, as a proxy of intrauterine growth, is causally associated with several aspects of brain structure that underlie the anatomy of neuropsychiatric disorders. Therefore, early interventions are crucial for children with low birth weight for optimizing neurodevelopment and mitigating the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders later in life. Second, we identified genes involved in processes including calcium and magnesium transport and cell cycle regulation may contribute to the causal associations mentioned above. Although evidence is limited, some of these findings align with established neurodevelopmental hypothesis, which could potentially inform drug development. Furthermore, we point to inhibitory neurons, pericytes, and even cerebrovascular cells could be the underlying cellular bases. These findings may provide potential directions for further mechanistic studies underlying intrauterine growth and cortical development.

This study has several limitations. First, sample overlap was inevitable as genetic data for both traits involved UKB participants, which may introduce bias into our estimations. However, the results of the MRlap analyses suggested the influence may not be substantial. Second, to minimize the bias due to population stratification, we restricted all genetic data used in this study to predominately individuals of European ancestry. Consequently, caution is required when generalizing our findings to other ethnic populations. Third, although we identified several genes and cell types potentially involved in the underlying mechanisms, experiments are warranted for further validation.

In conclusion, the results of this study provide evidence highlighting the associations between birth weight and various aspects of global cortical structure. We found that cis-regulated expression or protein level of genes involved in cellular metabolism, such as CNNM2 in magnesium transport, and brain cell types, such as inhibitory neurons, might underlie the biology of the observed association. Further studies are essential to validate these results and identify the related mechanisms.

Responses