Association between early exposure to famine and risk of renal impairment in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Globally, human health is adversely affected by impaired kidney function, and studies have shown it to be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease [1, 2]. In 2017, approximately 610,000 disability-adjusted life years have been lost due to impaired kidney function, and 1.4 million people have died from cardiovascular disease, which accounts for 7.6% of deaths (6.5 to 8.8) [3].

In the crucial early life period, low-protein diets can adversely affect kidney development, specifically the number of renal units. Bacchetta et al. discovered that children with intrauterine or extrauterine growth restriction have a lower glomerular filtration rate, and that extrauterine growth restriction is an emerging risk factor for long-term renal impairment in preterm newborns [4]. Malnutrition early in life may significantly affect the formation and number of renal units because approximately 60% of renal units grow during late gestation, renal development stops between 35 and 36 weeks of pregnancy [5], and malnutrition can permanently affect organ growth, structure, physiology, and metabolism [6]. The world’s largest Chinese famine (1959–1961) and the war-related famine that occurred in Europe during the Second World War (e.g. the Dutch famine (1944–1945) and the Siege of Leningrad (1941–1944)) are examples of such unfavorable events.

Over 800 million people worldwide were suffering from hunger in 2021, an increase of about 46 million from 2020. And by 2030, about 670 million people, or 8% of the global population, will still be hungry [7]. Historical periods of famine have been characterized by food shortages and nutritional deprivation, and experiencing famine early can affect a person’s mental and physical health in adulthood [8,9,10]. In recent years, people are increasingly interested in evaluating the impact of famine on human health, and to date, a substantial number of original research articles and reviews have been published linking early famine exposure to kinds of diseases in adulthood, such as metabolic [11] and cardiovascular disorders [12], renal disorders [13], and psychological disorders [14], among others [15,16,17], consistent with Barker’s study [18], existing famine research suggests that survivors have higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, and metabolic marker changes in adulthood.

Famine and malnutrition negatively impact kidney health in a variety of ways [13]. Several epidemiological studies have investigated the association between hunger in childhood and renal function impairment in adulthood. The results, however, are inconsistent. A few studies indicated people who suffered from famine in adulthood were significantly more likely to develop renal dysfunction compared to exposure in childhood and adolescence [19, 20], but other studies reported that exposure to famine in the fetal period significantly increases the risk of renal dysfunction, whereas no such association has been found in children and adolescents or young adults exposed [21, 22]. Therefore, we conducted the first systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the impact of early famine exposure (a famine-related exposure in fetal period, childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood) on renal impairment in adulthood. This review provides insights for health surveillance and population-level interventions by assessing the impairment of renal function caused by malnutrition exposure throughout all stages of life.

Methods

The meta-analysis was conducted on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [23] and registered on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42023424761).

Search strategy

We have systematically searched the articles published in Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, PubMed, and the Cochrane Library in any language. Medical subject headings (MeSH) were used together with text-words in the search for relevant articles, with search terms including “famine” (or “hunger” or “undernutrition” or “undernourishment” or “ malnutrition” or “malnourishment” or “starvation”) and “kidney disease” (or “CKD” or “ESKD” or “ESRD” or “dialysis” or “kidney” or “nephr” or “renal” or “glomerular filtration rate” or “GFR” or “eGFR” or “creatinine” or “BU)” or “UCAR” or “ urinary albumin excretion rate (UAER)” or “UAE” or “urinary albumin” or “UREA”) (Supplementary Table 1).

Two investigators (MTH and XZ) independently performed title and abstract screening based on study selection criteria after removing duplicates and identified potentially relevant articles for the full-text review. Then two authors (MTH and XZ) independently performed the full-text review and collaborated to determine the final list of articles to be included in the review. If there were discrepancies, they would be resolved through discussion and adjudication with a third investigator.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In the study, the term “impaired renal function” encompasses all phases of chronic kidney disease and various markers of renal function decline, such as reduced eGFR, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR), Scr, urinary albumin excretion rate, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), blood urea, and urinary albumin (UA) [24].

All studies that satisfied the following criteria were included in this analysis: (1) the original research was conducted on humans of all ages; (2) people who suffered from famine; (3) continuous or dichotomous variables (indicators of renal function) were reported; (4) if the same subjects’ data had been published multiple times, the most recent and comprehensive study was chosen; (5) articles written in any language, if necessary, translate potential research that is not in English with the help of translation software or translators; (6) articles published prior to May 1st, 2024; (7) all study designs or experimental designs. Articles were disqualified on the basis of the following criteria: (1) animal experiments; (2) editorials, letters, or commentary, etc; (3) people suffering from infectious diseases or other diseases that may affect the outcome.

Definitions

Fetal exposure (born 1959–1961), child exposure (0–9 years old, born 1949–1959), adolescent exposure (10–17 years old, born 1941–1949), adult exposure (over 18 years old, born before 1941) and unexposed (born after 1962). Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a kind of chronic progressive destruction of kidney structure and function caused by various reasons. The course of disease lasts more than 3 month and the most recent classification includes causes of disease, levels of GFR (6 categories), and levels of albuminuria (3 categories) [25].

Data extraction

The following data were independently extracted from each study by two researchers: (1) name of the first author; (2) publication time; (3) study design; (4) total patient population; (5) the participants’ age; (6) famine duration; (7) famine exposure; (8) index values of renal function measurements. For the description of the results, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were used to describe the continuous results. For categorical variables, odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI were used.

We extracted the mean and SD for unexposed and famine-exposed participants in each period and for reported renal function indicator values. For categorical variables, OR and 95% CI of renal function impairment for each period of famine exposure compared with unexposed individuals were extracted. In addition, we did not impose excessive restrictions on any of the indicators’ measurements.

Risk of bias and certainty of evidence assessment

The quality of the studies was independently assessed by two researchers (MTH and XZ), and discrepancies were resolved by a third researcher. The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Exposure (ROBINS-E) [26] tool is used to assess the risk of bias in cohort studies in observational epidemiological research. Two authors (MTH and XZ) rated the risk of each domain as low, medium, high, very high, or some concern, and Supplementary Table 2 provides detailed descriptions and decision results for each domain in ROBINS-E. Cross-sectional studies were evaluated by utilizing the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) checklist [27]. If the response was “yes,” the item received a score of “1” and if the response was “no” or “unclear,” the item received a score of “0”. The final quality evaluation results were as follows: 0–3, poor quality; 4–7, moderate quality; ≥ 8, excellent quality. The quality evaluation results are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system was used to evaluate the quality of outcomes. As a result of GRADE, evidence quality will be rated as “high,” “moderate,” “low,” or “very low.” The results of GRADE would then be analyzed using GRADE Pro software to create a summary of finding table. (Supplementary Table 4) [28].

Statistical analyses

We analyzed differences using mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous variables. When the data were not shown as Mean ± SD, SD and Mean were calculated using the methods described by Wan et al. [29] and Luo et al. [30]. For categorical variables, we analyzed using OR and 95% CI, and both in cases where only two or more studies used the same outcome measures to estimate a combined effect size. The I2 index and Cochran’s Q tests were used to assess study heterogeneity. When I2 ≤ 50%, and p > 0.1, heterogeneity was accepted, and a fixed-effects model is used. When I2 > 50, and p < 0.1, heterogeneity is significant, and a random-effects model is adopted [31]. When there was heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were performed for each study, subgroup analyses and meta-regression were conducted to determine the source of heterogeneity, and publication bias was analyzed using funnel plots and Egger’s test. Sensitivity analyses (excluding one study at a time) was conducted to test the stability of the pooled results [32]. STATA Version 17 and RevMan Version 5.4 were used for all analyses, unless otherwise stated, p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. In addition, we repeatedly analyzed all the results by using the fixed effect model to increase the credibility of the results.

Result

Study selection

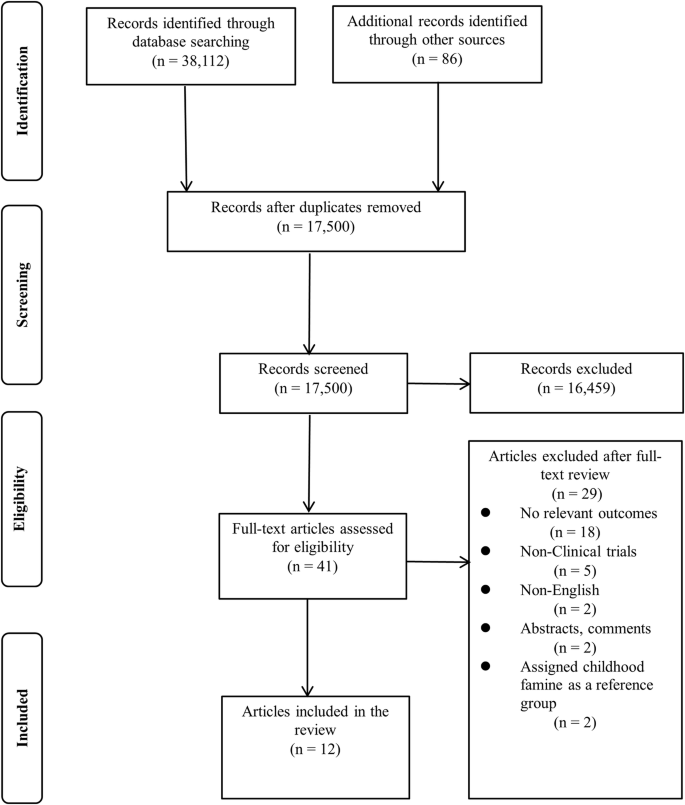

The database search method is depicted in Fig. 1. Based on the aforementioned inclusion criteria, we searched a total of 38,112 articles from databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane, and Scopus) and other sources. After title/abstract screening and removing duplicate articles, 41 articles qualified for full-text review. In addition, 29 of these 41 articles were excluded for a variety of reasons. Finally, 12 observational articles were included in this study [20,21,22, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

The literature search and study selection process.

Study characteristics and study quality assessment

The characteristics of the included studies are displayed in Table 1. These articles were published between 2005 and 2022, with the majority published after 2014. The number of people of the included studies varied from 441 to 70543, and the proportion of male subjects ranged from 0% to 63.1%. One of these studies only analyzed urinary proteins and did not examine serum or plasma samples from subjects [39]. The majority of the studies were conducted in China, and others were conducted in the Netherlands [41] and Ethiopia [35]. Of the 12 articles included in this meta-analysis, four articles [21, 22, 35, 38] described the relationship between famine and CKD, six studies described the effect of famine on GFR [20,21,22, 34, 35, 38], and five studies reported the effect of famine on Scr [21, 33,34,35, 38]. Blood uric acid index values analyzed as a categorical variable in three studies [36, 37, 40] and as a continuous variable in four [33, 34, 36, 38]. Proteinuria [39], microalbuminuria [41] and urea nitrogen [33] were mentioned in three different documents respectively. ROBINS-E was used to assess the quality of the included cohort studies. We found most included studies had a moderate or high risk of bias (Supplementary Table 2). For cross-sectional studies, AHRQ checklists were used. All included cross-sectional studies were rated as ‘good’ or ‘fair’ quality (Supplementary Table 3).

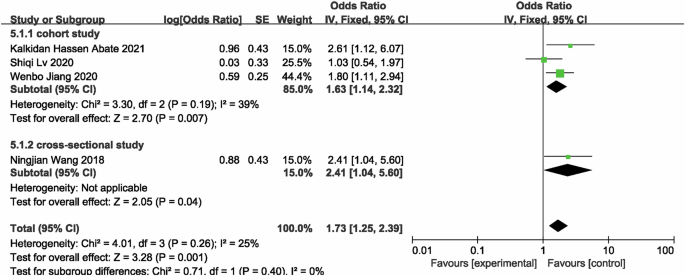

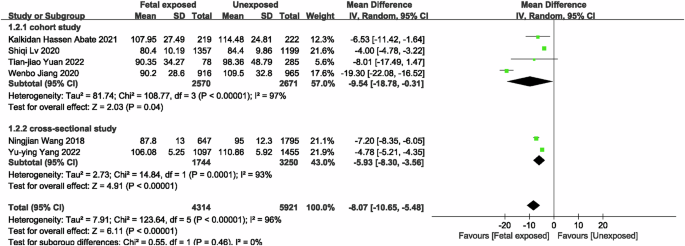

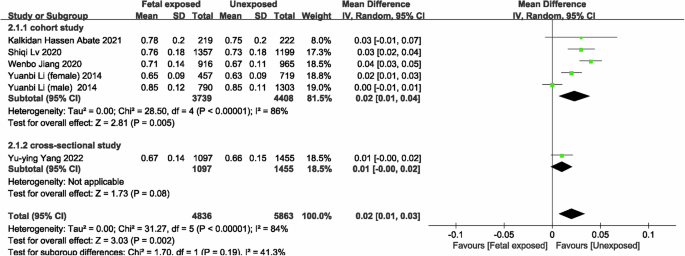

Fetal exposure to famine

Four studies [21, 22, 35, 38] were included to evaluated the risk of CKD in famine-exposed and unexposed individuals during the fetal period. The results indicated that famine exposure during the fetal period was up to 1.73 (OR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.25, 2.39; p = 0.001; I2 = 25%; Fig. 2) times more likely to result in CKD than in unexposed individuals. For renal function, six studies [20,21,22, 34, 35, 38] with 4314 famine-exposed fetal participants and 5921 unexposed individuals for comparison of eGFR between famine-exposed fetal and unexposed individuals were included. The results demonstrated that eGFR levels in famine-exposed fetal subjects were decreased by 8.07 ml/(min*1.73m2) (95% CI: −10.65, −5.48; p < 0.00001; I2 = 96%; Fig. 3). Due to the large heterogeneity, subgroup analysis and meta-regression by sample source, gender, and number of subjects were conducted. As the results (Supplementary Table 5) indicated that these factors were not the cause of the large heterogeneity. Since only one study was conducted outside of China, subgroup analysis by country was not performed. Sensitivity analysis revealed stable results (Supplementary Fig. 1). Famine exposure in fetal subjects was associated with a 0.02 mg/dL (MD = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.03; p = 0.002; I2 = 84%; Fig. 4) increase in Scr [21, 33,34,35, 38] levels while UA [33, 34, 36, 38] (MD = 3.88, 95% CI: −2.27, 10.03; p = 0.22; I2 = 78%; Supplementary Fig. 2) and hyperuricemia (HUA) [36, 37, 40] (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.90, 1.51; p = 0.25; I2 = 50%; Supplementary Fig. 3) were not observed to be associated with fetal period exposure to famine. Huang et al. [39] hypothesized that rural women exposed to the Chinese famine during pregnancy and the early postnatal period had elevated proteinuria levels in adulthood, consistent with the results of the Dutch famine [41], which produced a higher rate of microalbuminuria in those exposed to the famine during the middle of gestation compared to those who did not experience the famine (adjusted OR = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.4, 7.7).

Forest plot of fetal exposure to famine associated with risk of developing CKD in adulthood.

Forest plot of the associations between fetal exposure to famine and eGFR.

Forest plot of the associations between fetal exposure to famine and Scr.

Childhood exposure to famine

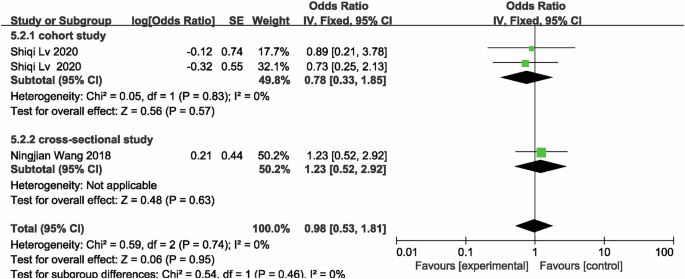

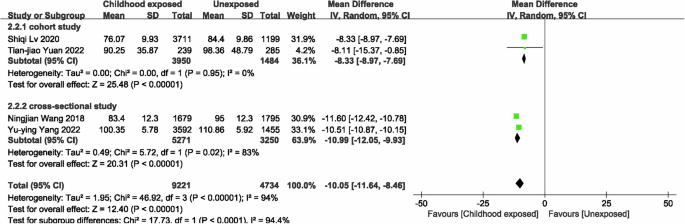

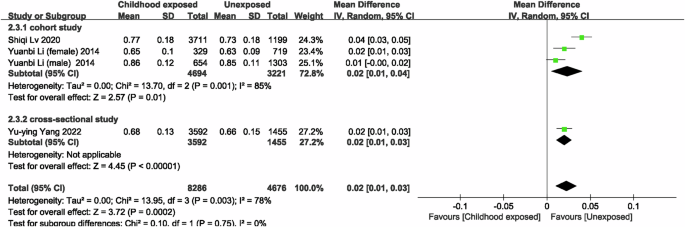

In the meta-analysis of famine exposure in childhood, one of the studies treated childhood famine exposure as two separate studies, so there were a total of four studies [21, 22] comparing the risk of CKD in famine-exposed versus unexposed individuals in childhood, and the results showed no difference in the risk of CKD (OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.53, 1.81; p = 0.95; I2 = 0%; Fig. 5) between famine-exposed and unexposed individuals in childhood. We included 6 studies [20,21,22, 34] to compare eGFR between famine-exposed and unexposed childhood, and the results indicated that famine-exposed childhood subjects had a decrease in eGFR levels by 10.05 ml/(min*1.73 m2) (95% CI: −11.64, −8.46; p < 0.00001; I2 = 94.4%; Fig. 6), and subgroup analyses and meta-regressions, as shown in Supplementary Table 6, indicate that publication year and gender were not sources of heterogeneity. In subjects exposed to famine in childhood, Scr [21, 33, 34] levels increased by 0.02 mg/dL (MD = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.03; p = 0.0002; I2 = 78%; Fig. 7), whereas UA [33, 34, 36] (MD = 8.00, 95% CI: −2.20, 18.21; p = 0.12; I2 = 92%; Supplementary Fig. 4) and HUA [36, 37, 40] (MD = 1.11, 95% CI: 0.89, 1.37; p = 0.36; I2 = 48%; Supplementary Fig. 5) were not associated with famine exposure in childhood.

Forest plot of childhood exposure to famine associated with risk of developing CKD in adulthood.

Forest plot of the associations between childhood exposure to famine and eGFR.

Forest plot of the associations between childhood exposure to famine and Scr.

Adolescence/adult-exposed

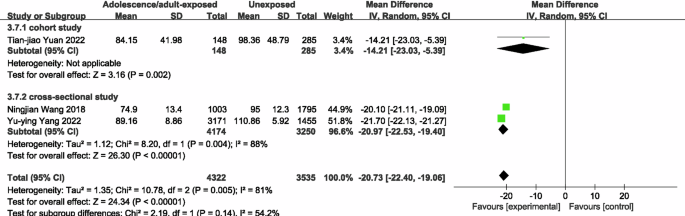

The results of the meta-analysis used to compare famine exposure during adolescence/adult and non-exposure showed that famine exposure during adolescence/adult had a decrease in eGFR [20, 22, 34] levels of 20.73 ml/(min*1.73 m2) (95% CI: −22.40, −19.06; p < 0.00001; I2 = 81%; Fig. 8) compared to unexposed subjects. Famine exposure during adolescence/adult subjects had a 24.81 umol/L (95% CI: 1.13, 48.48; p = < 0.00001; I2 = 97%; Supplementary Fig. 6) increase in UA [34, 36] compared with unexposed subjects, and famine exposure during adolescence had a 22.13 umol/L (95% CI: 3.58, 40.68; p = 0.02; I2 = 95%) increase in UA levels; famine-exposed subjects in adolescence/adulthood had up to a 1.78 (OR = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.03, 3.07; p = 0.04; I2 = 86%; Supplementary Fig. 7) fold greater odds of developing HUA [36, 40] compared to unexposed subjects. The included literature was limited, subgroup analyses for sources of heterogeneity and a meta-analysis of famine exposure and risk of CKD in adolescence/adulthood and other renal function indicators were not performed.

Forest plot of the association between adolescence/adult exposure to famine and eGFR.

Impact of age differences on study results

To verify that age differences may be the main reason for the observed association between famine exposure and adverse health outcomes [42, 43], we drew on previous research methods to define those born during the famine (fetal exposure) as famine births; participants born after the famine (unexposed) were defined as post-famine births; those born before the famine (child/adult/adolescence) births were defined as pre-famine births; studies that included both pre- and post-famine births combined these two groups further. Thus, three groups can be used as controls: post-famine births, pre-famine births, and combined pre- and post-famine births. The mean age of the three groups of the study (Supplementary Table 7) was compared for the main results (CKD, eGFR, Scr). Age information was absent from one study [33]. Pre-famine births were not included in two studies [35, 38]. Age differences between the three controls and famine births are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Effect sizes (OR or MD) for comparisons between famine births and the three controls were compared, and Supplementary Fig. 9 displays the effect values for the comparisons in each study, as well as the summary effects of comparing famine births with post-famine, pre-famine, and combined post-famine and pre-famine births. Using post-famine controls, all studies showed lower eGFR levels, higher Scr levels, and increased odds of developing CKD in famine births. However, using pre-famine controls and combined pre-famine and post-famine controls, most studies showed the opposite results, a result that may be related to the fact that the mean age of the post-famine group was smaller than the famine birth group, while the mean age of the pre-famine and combined control groups was larger. Supplementary Figs. 6–8 depicts the findings of a meta-analysis comparing the effects of famine using various control groups: a random-effects model comparing famine births to post-famine controls revealed that famine births had a higher risk of CKD (OR = 2.46, 95% CI: 1.64, 3.69, Supplementary Fig. 10A), lower levels of eGFR (MD = −8.07, 95% CI: −10.65, −5.48, Supplementary Fig. 11A), and higher levels of Scr (MD = 0.03, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.04, Supplementary Fig. 12A). In contrast, comparing famine births to combined pre- and post-famine controls revealed that famine births were not associated with changes in eGFR (MD = 3.20, 95% CI: −1.09, 7.50, Supplementary Fig. 11C), Scr (MD = −0.02, 95% CI: −0.04, 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 12C), and even CKD (OR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.51, 0.84, Supplementary Fig. 10C) had a protective effect. Famine births even had an overall “protective effect” over pre-famine births (CKD: OR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.33, 0.69, Supplementary Fig. 10B), (eGFR: MD = 6.90, 95% CI: 2.59, 11.21, Supplementary Fig. 11B), and (Scr: MD = −0.02, 95% CI: −0.04, −0.00, Supplementary Fig. 12B). Regardless of the control group used, there was significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0–99%). Thus, famine exposure may cause renal impairment, but this could be due to age differences.

Fixed effects meta-analyses

With the exception of the UA and HUA meta-analyses pertaining to exposure to famine during fetal and childhood periods, the findings of the fixed-effects meta-analysis demonstrated similarity to those of the random-effects meta-analysis, suggesting that the results of meta-analyses related to UA and HUA are unstable (Supplementary Figs. 13, 14).

Publication bias

A visual inspection of funnel plots was not performed due to the small number of studies included in this study. We used Egger to test for publication bias, which indicated that there was no publication bias in meta-analyses of the associations between famine exposure during fetal life (t = −1.43, p = 0.227), during childhood (t = 0.45, p = 0.686), and eGFR. The limited number of included datasets makes it difficult to estimate publication bias in meta-analyses of other outcomes.

Discussion

Famine in China is estimated to have caused 20 million to 30 million additional deaths [44], and infant mortality in the Netherlands increased to 922 per 10,000 during the famine [45].

Summary of the primary findings

We discovered that (1) eGFR levels were decreased in fetal, childhood, and adolescent/adult exposure to famine compared to unexposed individuals; (2) Scr levels were increased in fetal and childhood exposure to famine; and (3) the increase in UA levels and the likelihood of developing HUA were only statistically significant in adolescent/adult exposure to famine. The meta-analyses of the link between exposure to famine and the risk of developing CKD showed that famine exposure was linked to a higher likelihood of developing CKD in the fetal period compared to unexposed individuals, while no such association was found in childhood. Due to the limited volume of the study, additional indicators of renal function were not analyzed together.

Mechanisms and mediation

A growing number of research, including human studies and animal models, confirms that a suboptimal intrauterine environment is a major contributor to morphological and physiological alterations in the offspring organ development [46]. Fetal malnutrition triggers adaptive responses that selectively allocate nutrient supply to vital organs, neglecting others. This leads to lasting anatomical, physiological, and metabolic abnormalities [47, 48]. For example, inadequate nutrition during pregnancy can disrupt fetal kidney development, reducing the number of glomeruli. The reduction increases postnatal GFR, imposing an elevated workload on the kidneys. Over time, it can result in glomerular hyaline degeneration and glomerulosclerosis [49]. Adequate prenatal nutrition is crucial for optimal nephron endowment. The epigenetic perspective suggests that early-life exposure to adverse conditions may alter the epigenome, affecting gene expression and phenotype in ways that could predispose individuals to diseases later in life [50, 51].

Animal studies suggest that maternal malnutrition during pregnancy is linked to a reduced number of renal units in offspring, potentially leading to renal insufficiency in later life [52]. The underlying mechanisms include: 1) impaired Na+/K+-ATPase activity in the proximal tubule, which may contribute to malnutrition-induced renal dysfunction. In malnourished rats, Na+/K+-ATPase activity was decreased by 30%, and its immunodetection was reduced by 20%. In contrast, the activity of the insensitive Na+-ATPase, responsible for fine-tuning Na+ reabsorption, was increased threefold [53]; 2) disruption of the Notch signaling pathway, which is important for renal unit development. Maternal malnutrition can cause dysregulation of this pathway, characterized by decreased expression of Notch2, coactivators, and downstream targets, as well as increased levels of co-repressors [54]; 3) increased apoptosis and altered p53 methylation in malnutrition states, resulting in reduced glomerular numbers [55, 56]. In humans, kidney mass is directly proportional to the number of renal units [57]. Hughson, M. et al. demonstrated through autopsy that birth weight correlates with a reduction of approximately 250,000 glomeruli per kilogram [58]. Lower kidney mass is associated with fewer renal units and larger glomerular volume, predisposing individuals to glomerular hyperfiltration, glomerulosclerosis, and CKD [59, 60]. This may explain the findings in our study, where fetal starvation was associated with an increased risk of CKD, elevated Scr levels, and decreased eGFR.

Further investigation is required to elucidate the mechanisms linking adult renal dysfunction to malnutrition in children, adolescents, and adults. The number of renal units and glomeruli is influenced by various factors, including oxidative stress, alterations in the renin-angiotensin system and sodium-transporting proteins, renal sympathetic nerve activity, glucocorticoid action, and increasing age. Additionally, hormonal cascades, physiological mechanisms, morphological patterns, unhealthy lifestyle choices, and socioeconomic status all significantly impact renal health.

Limitations

When interpreting the results, it is important to take into account the limitations of the meta-analysis. First, the available pool of studies for this meta-analysis was constrained in terms of quantity; the sample sizes of the included studies varied significantly, and significant heterogeneity was discovered within them. More research is needed to determine whether other study characteristics influenced the results. Furthermore, we employed data from observational studies, which are susceptible to confounding. Additionally, most studies did not consistently account for crucial variables, and the effect of famine exposure itself may be confounded. Second, the included studies compared famine pre- and mid-birth with post-famine (unexposed) controls to assess the impact of early famine exposure on study outcomes, ignoring the fact that famine births were three years older on average than post-famine (unexposed) births. Moreover, renal dysfunction increased with age, meaning an age difference might explain the apparent famine impact observed in the majority of current studies. Most studies define famine exposure only by birth year or month, ignoring regional differences in famine intensity [61], which may lead to misclassification of famine exposure status. Furthermore, we are unable to rule out the possibility of confounding brought about by variation in the length and timing of famine experiences, past and present lifestyle changes, dietary modifications, and the existence of additional risk factors for NCDs and type 2 diabetes in later life. Third, due to higher mortality during the famine, the total amount of famine births included in studies is typically much lower than the number of pre- or post-famine births and the participants included in the studies may represent a healthier segment of the overall population. As a result, mortality bias may reduce the true impact of famine, and survivor bias poses a significant risk as well, since survivors of a famine may experience greater or lesser health issues than those of a famine with fewer or more short-term deaths. Fourth, the included studies were inconsistent in their measurements of renal function index values, which may have been exaggerated. Fifth, the Dutch famine lasted only 5–6 months and had a clear beginning and end point, whereas the Chinese famine of 1959–1962 lasted a long time and was imprecise, and the studies were inconsistent in terms of grouping of dates by date of birth, so age ranges or life stages that might overlap could not be completely excluded Sixth, the majority of the studies from China’s famine were included in this meta-analysis. Because of this, our results may be a better reflection of the Chinese famine. Not to worry too much about this issue, though, because similar results have been seen in other famine situations.

All of the aforementioned factors may affect the results’ credibility and may also explain the source of heterogeneity. Consequently, the findings should be carefully interpreted and used to generate hypotheses.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the evidence from this study indicated that suffering from famine in early life-stages may increase the risk of renal dysfunction in adulthood. Ensuring adequate and optimal nutrition early in life, during the important period of growth, is essential not only for lowering one’s risk of NCDs (chronic non-communicable diseases) but also for raising healthier children. We also make several suggestions for future studies to better estimate the effect of famine on renal function: (1) control for age differences between controls by attempting to find unexposed controls with a similar age structure at famine birth or use a more robust method such as difference-in-differences (DID), which is a method that exploits the effect of famine on renal function in addition to time or cohort analysis by taking advantage of the spatial changes and time or group changes exposed by famine [62]. Recent studies have also proposed a systematic approach to address age differences in studies of the Chinese famine and other famines [63, 64]. (2) because renal dysfunction has a genetic component, it is also necessary to determine whether parental health characteristics influence the risk of famine survivors developing renal dysfunction. (3) several studies have found that female students are more likely than male students to have impaired renal function as a result of famine exposure. However, because of the small number of included studies that were not analyzed by gender, more research is needed to determine whether sex-specific associations are the result of intersex biological differences or bias. (4) because the dietary structure, behavioral habits, and economic and social inconsistencies of the subjects in each locality may also affect the disease’s incidence, it is also necessary to investigate the investigated population’s dietary habits, lifestyle, and economic situation. (5) some studies have found a dose-response relationship between early famine severity and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in adulthood, and because the famine was long and widespread in China, and its magnitude varied from place to place, a famine severity scale would be useful in identifying potential dose-response effects [65, 66]. For example, consider the cohort size shrinkage index (CSSI), which is currently the most commonly used intensity measure for studying the 1959–1961 Chinese famine [67, 68].

Taken together, the results of these studies suggest that famine exposure may lead to renal impairment, but this may be a consequence of uncontrolled age differences between exposed and non-exposed groups; most current famine studies have methodological flaws that should be addressed in future research to produce more trustworthy estimates of the effects on famine and disease [69]. These efforts will provide critical evidence and policy suggestions for public health. The certainty of evidence in this meta-analysis is generally low or very low. Low certainty evidence indicated that the results found in the study may be different from the effect estimation. Therefore, more research is needed in the future to verify the association between famine and renal function impairment.

Responses