Association between white blood cell counts and the efficacy on cognitive function after rTMS intervention in schizophrenia

Introduction

Cognitive impairment is highly prevalent in individuals with schizophrenia1, with over 80% of patients showing a global cognitive performance that is more than one standard deviation below the mean of the general population2. Cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia is a core feature of the disease and is closely associated with prognostic and functional outcomes in schizophrenia, more so than any other psychotic symptom3,4,5. Patients with schizophrenia usually display several domains of cognitive impairments, including attention, processing speed, working memory, learning and memory, and executive functions6,7. This impairment is also present at high risk of developing the disorder, with severity increasing during the prodromal phases8,9. Longitudinal studies have shown that, in the absence of specific treatment, the severity of cognitive impairment is fairly stable over a lifetime2. However, the severity of cognitive impairment increases in some patients over time, indicating a possible progressive deterioration.

Although a variety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions have been used to improve cognitive impairment, the treatments of cognitive impairments remain complex, and there are currently no medications specifically approved for the treatment of cognitive impairment10,11. Many widely used antipsychotic medications, including first-generation antipsychotics, have been revealed to have little to no effect on cognitive performance and may even be detrimental12,13,14,15. Studies have found that high doses of first-generation antipsychotic drugs can impair procedural learning and memory16. Recent research has focused on non-pharmacological interventions, such as psychosocial interventions, cognitive remediation, physical exercise (PE) interventions, and aerobic PE17. Another intervention that is currently receiving increasing attention in the treatment of cognitive impairments is non-invasive brain stimulation, including repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

rTMS, as a non-invasive brain stimulation technique, has shown efficacy and potential in the treatment of depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder18,19,20,21. Its use in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) has been linked to cognitive improvements in mental diseases22,23,24, through modulating cortical excitability and metabolic activity as well as altering functional connections between different brain regions25,26,27,28. However, the efficacy of rTMS on cognitive impairments in schizophrenia remains unclear19,20,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. The varying results across studies regarding the efficacy of rTMS may be due to the disease status of the patients, the heterogeneity of schizophrenia, and the characteristics of the rTMS stimulation (including intensity of stimulation, frequency, and duration of treatment). The lack of evidence for a generalized cognitive effect does not currently allow rTMS to be used as a top treatment for cognitive impairments in schizophrenia. Therefore, the clinical application of rTMS still requires more research to determine its optimal treatment protocol and mechanisms for specific subgroups of this population.

In recent years, dysregulation of immunological and inflammatory processes has been frequently observed in schizophrenia and leads to cognitive impairments through neurotoxic effects37,38. Recent reports have shown that enhanced inflammatory processes reduce functional brain connectivity and neuroplasticity in certain neural circuits that are closely associated with cognitive functions39. System inflammation can disrupt the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and promote the infiltration of peripheral monocytes and proinflammatory cytokines, leading to the stimulation of microglia and an increase of neuroinflammation40. Total white blood cell (WBC) count is a routinely measured marker of systemic inflammation. WBC, monocytes, and neutrophils were significantly higher in patients with schizophrenia vs. controls with small-to-medium effect sizes41. Given that previous studies have shown that rTMS can alter neuroplasticity related to the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) and LTD42,43,44,45,46,47,48, it is possible that the inflammation pathway may be associated with response to rTMS procedures in individuals. Indeed, studies have shown that rTMS reduces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL-6) resulting from microglia activation, thereby reducing neuronal damage49. In addition, rTMS was reported to affect the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mice, reducing the release of proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α and inhibiting the neuroinflammatory response50. This signaling pathway plays a role in regulating the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, which in turn affects the production of proinflammatory cytokines51. Similarly, in patients with depression, the therapeutic mechanism of rTMS in cognitive impairments has been reported to be associated with neuroinflammatory processes mediated by IL-β52.

However, few studies have been conducted to investigate the immune biomarkers of schizophrenia and the therapeutic effects induced by brain stimulation on psychotic symptoms53,54. To our knowledge, there was no study has examined the impact of inflammatory markers in the cognitive response to rTMS. Considering the potential anti-inflammatory effects of rTMS in the periphery and in the brain reported in previous literature, theoretically, inflammation could also potentially have an impact on rTMS outcomes in schizophrenia. In particular, the DLPFC is very vulnerable to stress and inflammation. Therefore, this study was designed to explore whether the blood inflammatory biomarkers correlated with the efficacy of high-frequency rTMS targeted on left DLPFC in cognitive impairments in patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

Patients

Participants were eighty-four individuals aged between 27 and 69 years (mean ages: 53.0 ± 8.9), diagnosed with schizophrenia according to the DSM-5 criteria. All participants were male and Han Chinese. Our investigation was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the hospital. Written, informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were described in a previous study55. Specific inclusion/exclusion criteria included male patients who had been treated with a stable dose and type of antipsychotics for more than 2 years. Patients were excluded if he/she had been diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders or other major physical disorders, or had received modified electric convulsive treatment (MECT) in the past 6 months.

This study is a secondary analysis of a previous randomized, controlled study of left DLPFC rTMS treatment55. Briefly, all recruited patients were randomized in a ratio of 1:1:1 into the sham group (n = 28), 10-Hz rTMS stimulation frequency group (n = 28), and 20-Hz rTMS stimulation frequency (n = 28) group. Randomization numbers were generated by a computer. Investigators, raters, and participants were blinded to the participants’ randomization numbers. Based on previous systematic reviews56,57, rTMS was delivered in one session each workday, five sessions per week for six consecutive weeks. The patients received rTMS for a total of 30 times. In the 20-Hz group, 20-Hz rTMS stimulation frequency occurred at a power of 110% of motor threshold (MT) for 2-s intervals with 28-s intervals. In the 10-Hz group, 10 Hz stimulation frequency occurred at an intensity of 110% of MT for 3-s intervals with a 27-s interval. In the sham group, the protocol was the same as in the 10-Hz group except for the sham coils.

After the treatment, all participants were followed up with the cognitive functioning evaluation at the end of week 24. 21 participants were lost to follow-up (Supplementary file 1).

Clinical measurements

The clinical symptoms were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scales (PANSS) by the experienced psychiatrists after a training course58. It includes the positive symptom subscale (PANSS-P), negative symptom subscale (PANSS-N) general psychopathology subscale scores (PANSS-G), and the total score. Repeated assessment found that the interobserver correlation coefficient was maintained at >0.8 for the PANSS total score.

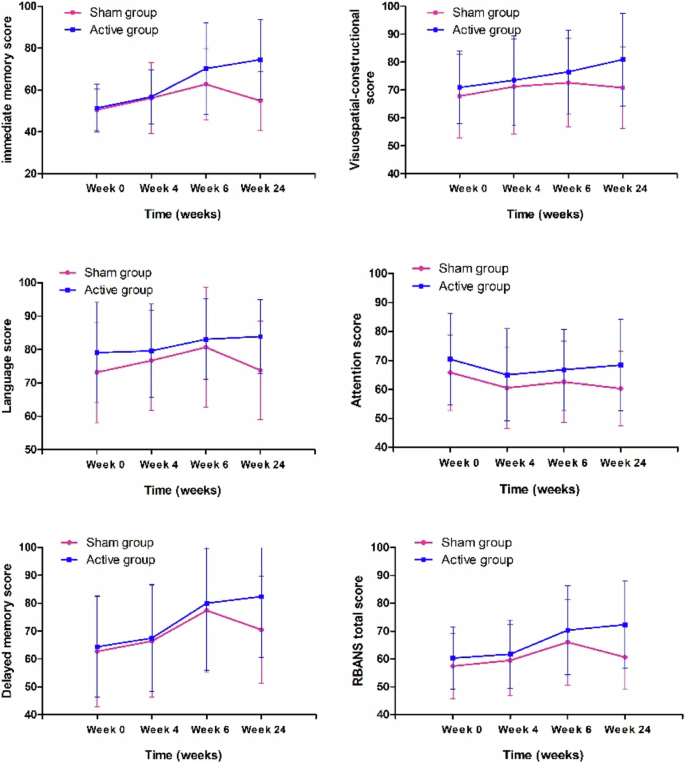

Cognitive functioning was evaluated using the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)59 at baseline and at the 2nd, 6th, and 24th weeks by four raters. The RBANS includes a composite score and 5 age-adjusted index scores. The battery tests consist of immediate memory subscale (comprised of List Learning and Story Memory tasks), visuospatial-constructional subscale (comprised of Figure Copy and Line Orientation tasks), language subscale (comprised of Picture Naming and Semantic Fluency tasks), attention subscale (comprised of Digit Span and Coding tasks), and delayed memory subscale (comprised of List Recall, Story Recall, Figure Recall, and List Recognition tasks).

Data analysis

All data lost to follow-up were analyzed using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method, therefore the analysis was done at the LOCF endpoint for all participants.

Group comparisons were performed using ANOVA or X2. The efficacy analysis was performed by the repeated-measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA) between the different stimulation frequencies or between two subgroups. In the present investigation, if the interaction effects between the treatment group and time on cognitive functioning were significant, we would further analyze the differences in the improvements of cognitive performances in the active rTMS groups. Comparisons of cognitive improvements were analyzed with non-parameter tests.

Correlation analysis was used to determine the associations between cognitive functions or cognitive improvements and blood biomarkers. Linear regression analyses were used to identify the predictive biomarkers for cognitive improvements in patients. Considering that educational years, age, marital status, smoking status, duration of illness, and dose of antipsychotics were previously reported to be associated with cognitive functions in schizophrenia, we compared these potential confounding variables between the two groups. Variables with statistically significant differences were added as covariates in the linear regression analysis.

Results

Baseline comparisons

We found 56 patients in the active group and 28 in the sham group. Patients in the sham group were older (F = 5.2, p = 0.03). No significant difference was observed in age of onset, duration of illness, smoking status, educational levels, marital status, hospital time, and dose of antipsychotics (all p > 0.05) (Table 1).

There were no significant differences observed in baseline cognitive functions, as measured by RBANS between the active and sham groups (all p > 0.05) (Table 2). However, negative symptoms and general psychopathology were more severe in the sham group than in the active group (all p < 0.05). The differences were 3.9 (95%CI: 0.7 to 7.3) for PANSS-N and 5.0 (95%CI: 1.3 to 8.6) for PANSS-G.

Comparisons of efficacy in clinical symptoms and cognitive functions over time

As reported in our previous study, we found no significant interaction effects between Times (4 time points) and Groups on the PANSS-P subscore, PANSS-N subscore, PANSS-G subscore, and total score in all participants (all p > 0.05)55.

We found significant interactions between Times and Groups on the RBANS immediate memory subscale (p = 0.02) and RBANS total scores (p = 0.04) in all patients (n = 84). We further found greater improvements in immediate memory (p < 0.001) and RBANS total scores (p = 0.03) in the 20-Hz rTMS group compared with the sham group, and the same greater improvements were also seen in the 10-Hz compared to the sham group (both p < 0.001), However, we did not find significant interactions between Times and Groups in attention subscale, delayed memory subscale, visuospatial-constructional subscale, and language subscale55.

Considering that both 10 Hz and 20 Hz showed significant effects on immediate memory compared with sham stimulation, we combined the two groups into the active group (n = 56) and compared the cognitive functions between the active group and the sham group. The RM ANOVA analysis conducted to examine the improvements in immediate memory between the active and sham groups revealed a significant interaction effect of Time × Group on immediate memory (F = 14.4, p < 0.001, effect size = 1.37), delayed memory (F = 4.3, p = 0.04, effect size = 0.61) and total RBANS score (F = 7.7, p = 0.007, effect size = 0.84) (Table 3) (Fig. 1).

There were significant interaction effects of time × group on immediate memory (F = 14.4, p < 0.001), delayed memory (F = 4.3, p = 0.04) and total RBANS score (F = 7.7, p = 0.007).

Comparisons in the changes in immediate memory, delayed memory, and RBANS total scores between the two groups revealed significant differences in immediate memory after the 24-week intervention (Z = 2.4, p = 0.02; Z = 2.4, p = 0.02; Z = 3.3, p = 0.001). The median changes in immediate memory, delayed memory, and total scores were 23.0 (9.0, 34.0), 15.5 (0, 32.3), 11.0 (0.8, 20.8) in the active group and 0 (−4.0, 10.5), 4.5 (0, 13.5), 2.5 (−2.3, 8.5) in the sham group.

Association between cognitive improvements and WBC counts in the active group

At baseline, correlation analysis showed no significant association between WBC counts and RBANS total score and its five subscale scores, including immediate memory subscale, visuospatial-constructional subscale, language subscale, attention subscale, and delayed memory subscale (all p > 0.05). Spearman correlation analyses showed that the baseline WBC counts were negatively associated with the changes in immediate memory after 24 weeks (r = −0.42, p = 0.004) (Table 4), but not after 2 weeks and 6 weeks (all p > 0.05). However, the baseline WBC counts were not associated with the changes in other cognitive domains after treatments (all p > 0.05). In addition, red cell counts, platelets, and hemoglobin were not associated with the changes in RBANS total score and its five subscale scores (all p > 0.05).

We further performed regression analysis to determine the association between the changes in immediate memory and WBC counts after controlling for confounding factors. Considering the small sample size (n = 56), we selected only the different variables between the active and sham groups that were correlated with changes in immediate memory at baseline. In this study, the independent variables included WBC counts, age, disease duration, baseline PANSS total scores, and baseline immediate memory. Linear regression analyses showed that WBC count was a predictor of improvements in immediate memory after rTMS treatment (β = −0.29, t = −2.00, p = 0.05, 95% CI: −4.9 to −0.06) (R2 = 0.16).

Discussion

The present study found a better efficacy of rTMS applied on the DLPFC for 6 weeks on immediate memory and delayed memory in patients with schizophrenia. In addition, baseline WBC counts were associated with improvements in immediate memory after treatment with rTMS in patients. Our findings provide evidence for the potential use of rTMS as a supplement to conventional medications for schizophrenia and point the way for future research.

We found that rTMS treatment lasting 6 weeks was effective on immediate memory and delayed memory in patients with schizophrenia. Our findings were consistent with a previous study from Barr et al, which found that 4-week, bilateral, 20-Hz rTMS targeting DLPFC showed a significant beneficial effect on working memory measured by 3-back tasks32. Although rTMS treatment has shown some efficacy in improving memory in patients with schizophrenia, there is heterogeneity in the findings30,31,32,33,35,36. The impact of individual differences among patients on the efficacy of rTMS is multifaceted. Studies have reported that the course of illness, age, gender, educational attainment, medication status, different stages of the disease, and varying symptom severities might respond differently to rTMS60, leading to heterogeneity in results across different studies. Therefore, it is necessary to take full account of individual differences in brain structure and function, cellular electrophysiological activity, and biochemical parameters when implementing rTMS treatment to improve treatment outcomes and develop personalized treatment plans.

We further found that patients with lower WBC counts showed more cognitive improvement after the administration of rTMS, but patients with higher WBC showed less improvement. The results of this study were inconsistent with a previous study of patients with treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders, which reported that TNF-α concentration was not a marker for treatment success in schizophrenia patients undergoing brain stimulation53. The heterogeneity between these two studies might be due to differences in brain stimulation methods (rTMS vs MECT). Our study provides the first evidence of the association between WBC and the cognitive efficacy of rTMS. WBC is a non-specific marker of inflammation and infection61,62. The higher baseline WBC counts in this study might suggest a higher level of systemic inflammation in these patients. Peripheral markers like WBC counts might reflect central inflammation63 and changes in WBC counts may reflect this central inflammation process. We speculate that the underlying mechanism for fewer improvements in those patients with higher WBC counts in schizophrenia may be due to the moderating effect of inflammation. Patients with high levels of inflammation are less responsive to rTMS, which targets neural circuits and may work worse in a low-inflammation environment. The neuroinflammatory hypothesis suggests that neuroinflammation is part of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia64,65,66. Previous observational studies support a close relationship between elevated WBC counts and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia67,68, indicating that the inflammatory response is associated with the development of schizophrenia and that WBC count is one of the hallmarks of inflammation in schizophrenia. Mendelian randomization studies have provided evidence of a causal relationship between WBC and schizophrenia, supporting the role of WBC in influencing the risk of schizophrenia69. Immune activation, as measured by increased circulating cytokines, has been associated with decreased cognitive function in the general population70,71, suggesting that inflammation may worsen cognitive function.

However, although studies suggest the role of peripheral immune activation in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, the central nervous system (CNS) has previously been considered an immune privilege site72. Recent studies support the concept of brain-immune interaction and observe the communication between the CNS and immune system73. Evidence indicates that there is a wide cross-talk between the neuroimmune system and neuroplasticity mechanisms under both physiological conditions and pathophysiological conditions74. We speculated that systemic inflammation, reflected by elevated WBC counts leads to activating brain-resident immune cells and releasing proinflammatory cytokines from activated microglia, which can bind to receptors on neurons and activate signaling pathways. Microglia activation and proinflammatory cytokine release can modulate neuronal activity, synaptic connectivity and plasticity, and neurotransmitters, leading to changes in mood, cognition, and behavior75. It is well known that rTMS can modulate the activity of the brain and neuroplasticity, and may also have indirect effects on the immune system based on brain-immune interaction. Patients with lower WBC counts might have a less active inflammation response and better brain functions, which may make them more susceptible to the modulatory effects of rTMS.

Despite these facts, we did not find any association of WBC counts with cognitive functions at baseline in this study. This may be due to the fact that we did not use sensitive assessment tools to assess cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia59,76. In summary, the association between baseline WBC count and cognitive improvement after rTMS treatment provides a new perspective on the treatment of schizophrenia. These findings need to be further validated in larger samples and multicenter studies.

There are several limitations to this study. First, all participants were men with schizophrenia, who had a different clinical manifestation to women. Thus, the findings were limited to male patients and were not generalized to female patients, which weakens the generalization of the findings in clinical practice. Second, individuals participating in the study must be able to provide informed consent, and therefore may not be fully representative of the real-world population who were suffering from schizophrenia. Third, it is better to disaggregate the impact of certain WBC subtypes (e.g., lymphocytes, neutrophils) to further specify their role in particular. However, we did not collect data on lymphocytes or neurotrophins. The lack of these data limits our ability to conduct in-depth analyses of their roles in specific responses to rTMS. Future studies may consider incorporating these indicators to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the roles of WBC subtypes in immune responses and rTMS. Fourth, while RBANS is a valid and validated tool, it is indeed a screening test, and no other test [e.g. the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB)] was used, which was a limitation in this study. Fifth, the sample size is small, which affects the ability to detect significant effects. We only found the beneficial effects of rTMS on one domain of cognitive functions, and the negative findings of other cognitive domains may be partly related to the low statistical power. Sixth, the associations between inflammation and response to rTMS were complex and may be influenced by unmeasured variables in the present study, such as individual genetic differences, comorbid conditions, regular exercise, and lifestyle.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that rTMS may be particularly beneficial for schizophrenia patients with lower baseline WBC counts than those with higher WBC counts. This study adds to the existing literature and paves the path for future research regarding considering immune biomarkers as a means to personalize rTMS treatments for regular clinical treatment of cognitive impairments in schizophrenia. While this study provides preliminary evidence, it makes a meaningful contribution to the field and attempts to address the multifaceted issue related to the therapeutic efficacy of rTMS. Further research with a large sample size and investigation of other immune markers was warranted to confirm this relationship and to examine underlying mechanisms that link neuroinflammation and treatment response.

Responses