Associations of traditional healthy lifestyle and sleep quality with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: two population-based studies

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), as with the previous term non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, represents a hepatic manifestation of a multisystem disorder [1] affecting over one third of the global population [2]. MAFLD carries significant morbidity and mortality, largely due to its progression to end-stage liver disease and severe extra-hepatic complications, which poses a major burden to all societies [1]. Despite a high prevalence and growing impact on world health, currently, there are no approved drugs and lifestyle modifications remain the foundations for the management of MAFLD, regardless of the histologic type [3,4,5].

Both individual healthy lifestyle behaviors, such as healthy diet [3, 6], active engagement in physical activity [3, 6, 7], restriction of alcohol [7] and cigarette smoking [8], and the combinations of these factors, termed as healthy lifestyles (HLS) [9, 10], have been epidemiologically linked with reduced risk for MAFLD-related diseases. Recently, disturbance in sleep, which is becoming more and more prevalent in modern society, has been emphasized as an emerging factor contributing to the development of several metabolic disorders, including MAFLD [11,12,13].

Though multiple studies have examined the contribution of an individual sleep behavior, such as sleep duration [14] and habitual snoring [15], or several [13] to the incidence of MAFLD, important gaps remain. First, given that health behaviors are always inter-correlated [16, 17], how much sleep behaviors mediate the association between HLS and MAFLD remain obscure. Moreover, the synergistic interaction between sleep behaviors and HLS on MAFLD outcomes has never been investigated. Second, as a complex process, sleep behaviors are typically correlated and may affect in a concerted manner. However, existing studies tended to simply use single variables, usually sleep duration, to represent sleep behavior, which only partly reflected overall sleep quality; thus, it is essential to use a comprehensive variable comprising different aspects of sleep. Besides, it is unknown whether an extended lifestyle metrics incorporating sleep could further improve risk stratification for MAFLD. Third, it remains unclear whether the findings are consistent among subpopulations of different age, sex, and racial or ethnic groups.

Here, we used data from two independent population-based studies, the Imaging Subcohort of South China Cohort (ISSCC) and the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (US NHANES), to evaluate the complex relations of sleep quality and traditional HLS with MAFLD outcomes.

Material and methods

Study population

ISSCC was conducted between March 2018 and October 2019 in Dongguan city, Guangdong, China. Details of the study design and data collection have been described previously [13, 18]. After excluding 419 participants, 5011 individuals from ISSCC with liver ultrasound were included in current analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1A).

US NHANES recruited a representative sample of civilian, community dwelling members of the US population using a stratified, multistage and probability-cluster design. In this study, NHANES survey cycle (2017–2018) with vibration controlled transient elastography (VCTE) were used [19, 20] and 3672 participants were included in current analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocols were approved by the US NHANES institutional review board, National Center for Health Statistics Research ethics review board, and the ethics committee of School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University (L2017-001), respectively. All participants from both cohorts provided written informed consent.

Assessment of sleep quality

Sleep behaviors, including bedtime, nocturnal sleep duration, insomnia, snoring, daytime sleepiness and daytime napping were collected though structured questionnaires. Details about collection and definition of sleep behaviors were provided in Supplementary Methods. If the participant was classified as at low-risk for each sleep behavior, he or she would receive a score of 1, otherwise receiving 0 [12]. Since sleep behaviors are highly interrelated and may affect metabolic homeostasis in a concerted manner, all six components were subsequently summed to obtain a healthy sleep score ranging from 0 to 6, with a higher score indicating a better sleep quality in ISSCC [13]. In US NHANES, only bedtime, nocturnal sleep duration, snoring and daytime sleepiness were used to create a similar score ranging from 0 to 4. Sleep quality was then designated as good, intermediate or poor, as described [12, 13]. More details were provided in Supplementary Methods.

Assessment of traditional lifestyle factors

Traditional HLS based on cigarette smoking, drinking, physical activity and diet quality, which coincided with recommendations from the World Health Organization [21], the latest clinical practice guideline from the American Gastroenterological Association [3] and the European Association for the Study of the Liver [22], was constructed as described [23]. More details about cohort-specific definitions for each lifestyle factor were provided in Supplementary Methods. Healthy traditional lifestyle behaviors were defined as: never smoking, no heavy drinking, high physical activity and good diet quality. Participants were categorized into three groups based on the number of healthy lifestyle behaviors: unfavorable (0-1 healthy behavior), average (2) and favorable (3–4), as described [23].

Definition of Liver Essential 5

Sleep quality and four traditional HLS factors were integrated to generate a more comprehensive score. All five components were summed to obtain the Liver Essential 5, ranging from 0 to 5, with a higher score indicating a healthier lifestyle. Participants were further divided into three risk categories: low (4–5 scores), moderate (3) and high (0–2). Although such a simple additive method has been widely used [23, 24], the underlying assumption was that the magnitudes of the associations between different lifestyle behaviors and liver diseases were identical, which might not be true. Thus, we also created a weighted Liver Essential 5, and a continuous Liver Essential 5 to further examine the robustness of our findings. More details for these sensitivity analyses were provided in Supplementary Method.

Outcome ascertainment

MAFLD was defined as having hepatic steatosis plus one of the following three criteria: overweight or obesity, presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus or evidence of metabolic dysregulation [1]. Two widely-used modalities with high sensitivity and specificity were used to define hepatic steatosis. In ISSCC, hepatic steatosis was defined by the presence of a diffuse increase of fine echoes in the liver parenchyma compared with the kidney or spleen parenchyma by abdominal ultrasound using 3.5-MHz transducer (Aplio400, TOSHIBA, Japan) [25]. In US NHANES, controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) ≥ 285 dB/m was used to define fatty liver quantified by VCTE using the FibroScan model 502 V2 Touch (Echosens, Waltham, MA) [26]. More details were provided in Supplementary Method. Moreover, at-risk metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) was defined by FibroScan-AST (FAST) score with a cut-off value of 0.35 [27, 28], and significant fibrosis was defined as liver stiffness of ≥8.0 kPa [29].

Covariates

Directed acyclic graphs were employed to select potential confounders and to identify the minimally sufficient adjustment set [30, 31] (Supplementary Fig. 2). Details were provided in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the study participants were summarized across sleep quality categories within each cohort. Differences among groups were assessed by analysis of variance and χ2 test for continuous and categorical variables in ISSCC, and by analysis of variance adjusting for sampling weights and Rao-Scott χ2 test in US NHANES to account for the complex survey design.

We used logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95%CI of outcomes associated with traditional HLS and sleep quality. All models were adjusted for age, gender, race (US NHANES), education, marriage and income level. Mediation analysis was performed to quantify how much of the association between traditional HLS and liver diseases was mediated by sleep quality. Furthermore, a stratified analysis was conducted to investigate the associations of traditional HLS with pre-specified outcomes across each stratum of sleep quality. Given the extremely low proportion of participants with 0 healthy behavior (n = 78, 1.56%) in ISSCC, we merged subjects with 0 and 1 healthy behavior together. Moreover, multiplicate interaction was assessed by introducing a two-way multiplicative term of traditional HLS and sleep quality, and an additive interaction was quantified by the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) and corresponding 95% CIs, the attributable proportion due to interaction (AP) and the synergy index (S). In addition, to assess joint associations, participants were further categorized into six groups according to traditional HLS (unfavorable, average, and favorable) and sleep quality (good, intermediate to poor), and the ORs for having MAFLD, at-risk MASH and significant fibrosis in different groups compared with those with good sleep quality and favorable traditional HLS were estimated. Moreover, to explore the potential for risk reclassification, prevalence of pre-specified outcomes classified by Liver Essential 5 was compared to those designated by traditional HLS. Additionally, E value method was used to evaluate residual confounding in the association observed [32]. Furthermore, to test the robustness and potential variations of our finding in different subgroups, we repeated main analysis stratified by age group (<60, ≥60 years), gender, race (US NHANES), marriage, education, income, presence of obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome.

We have also conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, we constructed a lifestyle score including baseline body shape. Second, a modified healthy lifestyle score in which never drinking instead of no heavy drinking was defined as healthy. Third, considering the potential role of obesity in the development of MAFLD, presence of obesity was further adjusted. Fourth, multiple imputation with chained equations was used to handle missing covariates and the influence of missing values were determined. Fifth, weighted Liver Essential 5 and continuous Liver Essential 5 were developed.

All statistical analyses were performed in SAS (version 9.4) and R (version 4.0.5), and statistical significance was defined as P values < 0.05 using two-tailed tests.

Results

Population characteristics

Table 1 showed basic characteristics of participants from ISSCC and US NHANES. Among 5011 participants from ISSCC (mean age 63.57 years, 40.1% men), only 333 (6.6%) had poor sleep, 2312 (46.1%) had intermediate sleep, and 2366 (47.2%) had good sleep. Among 3672 subjects from US NHANES (mean age 46.76 years, 49.1% men), 1003 (26.0%) had poor sleep, 1343 (37.3%) had intermediate sleep, and 1326 (36.7%) had good sleep. Despite an inconsistent trend of education and income level, individuals with good sleep quality were younger, more likely to be women, and had a lower prevalence of metabolic disorders. Healthy levels of traditional lifestyle behaviors were more prevalent among participants with good sleep. Basic characteristics between participants included or excluded from the current analysis were presented in Supplementary Table 1.

In ISSCC, 1423 (28.4%) MAFLD cases were detected by ultrasound. In US NHANES, 1374 (35.6%) MAFLD cases, 281 (7.7%) at-risk MASH cases, and 297 (7.0%) significant fibrosis cases were detected by VCTE. Regardless of the detection modality, the prevalence of MAFLD gradually decreased with improved quality of sleep in both cohorts. Moreover, a lower prevalence of at-risk MASH (P = 0.038) and significant fibrosis (P = 0.103) were also observed in subjects with good sleep in US NHANES (Table 1).

Joint associations of sleep quality and traditional HLS with MAFLD outcomes

Consistent with previous observations, traditional HLS was inversely associated with MAFLD in both cohorts, even after correcting for sleep quality and other covariates (all P-trend < 0.05, Table 2). The ORs without adjustment for sleep quality were larger. Per one increment of healthy sleep score was associated with 16–20% reduced risk of MAFLD after multivariate adjustment including HLS (Supplementary Table 2). When unfavorable traditional HLS was compared with favorable HLS, the proportion mediated by sleep quality for its association with MAFLD was 17.72% (7.04–72.00%) in ISSCC and 10.88% (5.40–18.00%) in US NHANES, respectively (Table 2). The results remained generally similar, when ideal body shape was included into traditional HLS, healthy level of drinking was defined as never drinking, further adjusted for obesity, or expanding analysis to those with imputed covariates (Supplementary Table 3). Notably, such a mediatory role of sleep quality in the association between traditional HLS and more advanced stage of MAFLD (8.08%, 95%CI: 2.02–19.00% for at-risk MASH; and 11.87%, 95%CI: 1.68–40.00% for significant fibrosis) was also found in US NHANES (Table 2).

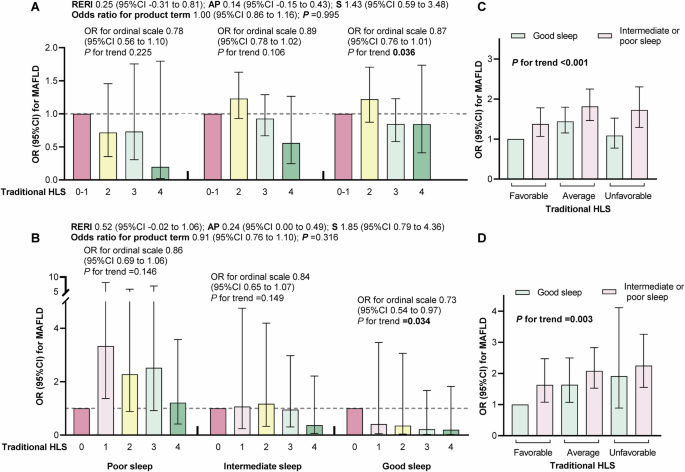

Though no significant interaction was found between sleep quality and traditional HLS on MAFLD in ISSCC (Fig. 1A) and US NHANES (Fig. 1B), the inverse association of traditional HLS with MAFLD was only significant in participants with good sleep (P-trend = 0.036 in ISSCC and P-trend =0.034 in US NHANES). Moreover, the joint effects between sleep quality and traditional HLS on MAFLD were significant in both cohorts (both P-trend <0.05, Fig. 1C, D). Compared with those with good sleep and favorable HLS, ORs for individuals with poor sleep and unfavorable HLS were 1.72 (1.29–2.30) in ISSCC and 2.25 (1.55–3.26) in US NHANES, respectively. Results were not materially changed in all sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, similar joint effects between sleep quality and traditional HLS on at-risk MASH and significant fibrosis were also observed in US NHANES (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4A, B).

A, C The Imaging sub-cohort of South China Cohort (ISSCC). B, D The US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Models included US population and study design weights to account for the complex survey design. Odds ratio (95%CI) were adjusted for age, gender, race (only US NHANES), education, marriage and income level. Multiplicative interaction was evaluated using odds ratios for the product term between sleep quality and traditional healthy lifestyles, and additive interaction was evaluated using relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI), the attributable proportion due to interaction (AP) and the synergy index (S) between sleep quality (poor versus good) and traditional healthy lifestyle (0 to 1 behavior versus 3 to 4 behaviors). AP attributable proportion due to interaction, HLS healthy lifestyle, MAFLD metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, OR odds ratio, RERI relative excess risk due to interaction, S synergy index.

Association between Liver Essential 5 and MAFLD-related outcomes

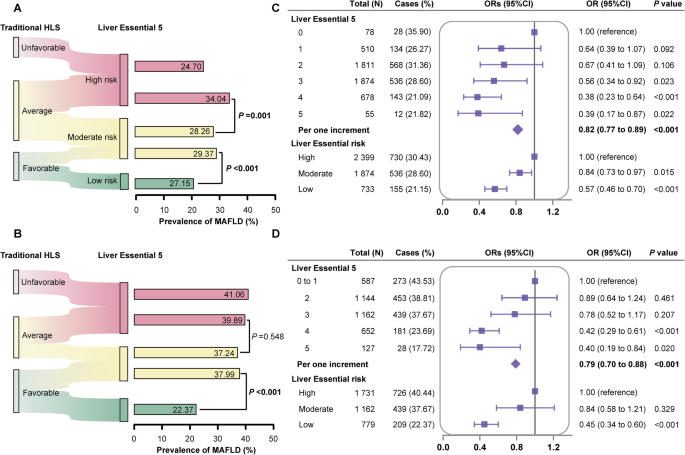

Given their complex interactions on MAFLD and its advanced stage, a more comprehensive lifestyle score, which integrated traditional HLS and sleep behaviors, was then developed and named Liver Essential 5. Of note, Liver Essential 5 improved the risk stratification on MAFLD on top of traditional HLS (Fig. 2A, B). For participants with average traditional HLS, about 60% of them were reclassified into high-risk group by Liver Essential 5. Notably, about 45% of individuals previously considered as following a favorable traditional HLS were further reclassified into moderate-risk group by Liver Essential 5, suffering from a substantially higher prevalence of MAFLD in both cohorts (ISSCC: 29.37% versus 27.15%, P < 0.001; US NHANES: 37.99% versus 22.37%, P < 0.001). Similar trends of risk stratification by Liver Essential 5 were also found on at-risk MASH and significant fibrosis in US NHANES (Supplementary Fig. 4C, D).

Liver Essential 5 showed risk re-classification potential on MAFLD on top of traditional healthy lifestyles in (A) the Imaging subcohort of South China Cohort (ISSCC) and (B) the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Association of Liver Essential 5 and MAFLD in (C) the Imaging subcohort of South China Cohort (ISSCC) and (D) the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). All models were adjusted for age, gender, race (US NHANES), education, marriage and income level. The odds ratio (95%CI) and P values in US NHANES included the US population and study design weights to account for the complex survey design. MAFLD metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, OR odds ratio.

Each one-point increase in Liver Essential 5 was associated with 18–21% reduced risk for MAFLD in both cohorts (ISSCC: OR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.77–0.89; US NHANES: OR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.70–0.88; Fig. 2C, D). When Liver Essential 5 was further designated into risk categories, compared with those in high-risk group, adjusted OR (95%CI) of low-risk group was 0.57 (0.46–0.70) in ISSCC and 0.45 (0.34–0.60) in US NHANES, respectively. The protective role of adhering to Liver Essential 5 was even stronger on advanced stage of MAFLD, including at-risk MASH (OR = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.48–0.78 for per one increment, Supplementary Fig. 5A) and significant fibrosis (OR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.65–0.93 for per one increment, Supplementary Fig. 5B). Results were basically the same whether considering each component’s association with the outcome by creating weighted Liver Essential 5 or increasing the sensitivity to interindividual differences by developing continuous Liver Essential 5 (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). Likewise, incorporating healthy body shape, using never drinking, further adjusting for obesity, or expanding to participants with imputed covariates did not substantially alter the results (Supplementary Table 7).

Subgroup analyses

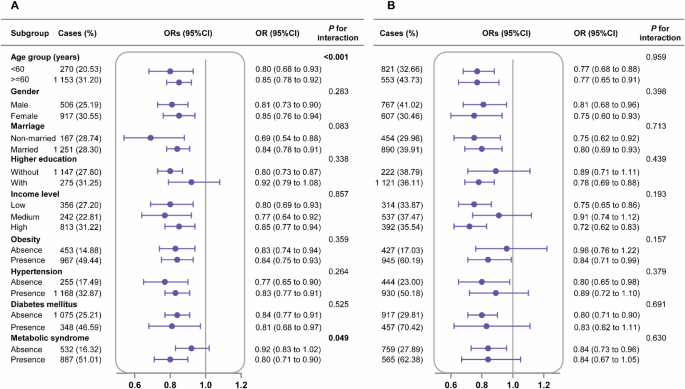

In ISSCC, the inverse associations between Liver Essential 5 and prevalent MAFLD were stronger in the young and participants with metabolic syndrome (both P-interaction <0.05, Fig. 3A), whereas we did not observe any significant interactions with gender, marriage, education, income and presence of obesity, hypertension and diabetes mellitus in both ISSCC and US NHANES (Fig. 3A, B). Moreover, the associations were similar across race group in US NHANES (P-interaction=0.245). These results suggested that promotion of Liver Essential 5 may enhance liver health in the general population, and may offset the socioeconomic inequality in health.

A The Imaging sub-cohort of South China Cohort (ISSCC). B The US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). All models were adjusted for age, gender, race (US NHANES), education, marriage and income level, except for itself. The odds ratio (95%CI) and P values in US NHANES included the US population and study design weights to account for the complex survey design. OR odds ratio.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that traditional HLS was inversely associated with higher risks of MAFLD-related outcomes, and 4.66–17.72% of the associations were mediated by sleep quality. Joint effects of traditional HLS and sleep quality were significant on MAFLD, at-risk MASH and significant fibrosis. Liver Essential 5, an extended lifestyle metrics incorporating the emerging risk factor of sleep quality showed significant risk reclassification potential for MAFLD outcomes on top of traditional HLS composed of smoking, alcohol, physical activity, and diet. These findings underpin the importance of promoting good sleep quality in combination with other traditional low-risk lifestyle factors in current healthcare guidelines to control the global burden of MAFLD.

As an essential process for human health [11], several pieces of evidence have demonstrated a close correlation between sleep behaviors and other more traditional lifestyle factors. For instance, a systematic review of 29 studies found a positive association between healthy diet and good sleep quality [33]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of 950 adults reported a significant improvement in sleep quality by exercise intervention [34], suggesting a collaborative potential of sleep quality with traditional lifestyle factors to influence health conditions. However, previous studies typically examined the association of sleep quality and traditional HLS with MAFLD separately, and included each other as covariates only [13, 14, 35]. Our study, by contrast, extended the findings by providing a joint effect of sleep quality and traditional HLS on MAFLD and its severe stages. Overall, 4.66–17.72% of the associations between traditional HLS and MAFLD outcomes can be explained by sleep quality. Besides, sleep quality also mediated the associations of traditional HLS with at-risk MASH (8.08–9.88%) and significant fibrosis (11.87–13.13%). Intriguingly, even in those with favorable traditional HLS, having a good sleep quality could lead to 38% and 63% risk reduction on prevalent MAFLD in two cohorts. These findings were directly supported by recent studies in UK Biobank [36, 37] showing that a healthy sleep pattern could offset the harmful effects of unfavorable lifestyles on cardiovascular disease [36] and mental disorders [37]. The implications of these disproportionately worse outcomes in individuals with poor sleep, despite a similar, traditionally defined HLS, are twofold. First, public health interventions could increase their impact by broadening the range of lifestyle factors targeted. Second, at individual-level, lifestyle interventions should be both broadened to include sleep quality and strengthened in individuals with poor sleep to be proportionate to need.

Driven by the rising prevalence of sleep disorders and its independent contribution to overall and cardiometabolic health, the American Heart Association has recently proposed Life’s Essential 8 (LE8), which additionally includes sleep duration to better reflect cardiovascular health [38]. However, LE8 only focused on sleep duration but failed to consider the complex interconnections of sleep behaviors, a shortcoming which had been acknowledged by itself [38]. Moreover, alcohol drinking was also not considered by LE8. However, absence from heavy drinking is strongly advocated by the latest clinical practice for the management of MAFLD [22]. Nevertheless, the protective associations of LE8 with MAFLD [39] was further supported by our findings. Of note, our study provided evidence that combinations of sleep quality and traditional HLS interacted synergistically and resulted in stronger associations with MAFLD outcomes, as reflected by risk reclassification potential of Liver Essential 5 on top of traditional HLS. In the present population, each one-point increase in Liver Essential 5, an extended lifestyle metrics incorporating sleep quality together with traditional HLS, led to 18–21% reduction in the risk for MAFLD in two cohorts, and 38% and 22% reduced risk for at-risk MASH and significant fibrosis, respectively. The high prevalence of MAFLD outcomes that was identified using this approach provide valuable implications for both primary and secondary prevention of liver health. Particularly, when adopting Liver Essential 5, about half of the individuals with moderate or most healthy traditional HLS, who were thus deemed as at a low risk for MAFLD and the more advanced stage of at-risk MASH or fibrosis, would be re-classified into higher risk categories. Given the constant rising prevalence and incidence of MAFLD globally [1], and large proportion of individuals reclassified, the adoption of such a comprehensive lifestyle metrics may yield considerable gains. Although lifestyles vary substantially with age, race and geographical locations of target population, and may also greatly influenced by socioeconomic status, and diseases status [40, 41], our study provided evidence that Liver Essential 5 worked equally well in different populations. In this regard, our findings highlight the urgency for strategies and measures to promote sleep quality, in controlling the burden of MAFLD.

Limitations

The use of large population-based sample from both China and western populations and the inclusion of two major detection techniques of hepatic steatosis proposed by the latest international expert consensus [1] support the generalizability of our results of extended lifestyle metrics and its associations with MAFLD outcomes therewith. Additionally, we have also included various subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses to ensure the robustness of the results. Nevertheless, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, information on sleep quality and lifestyles was self-reported, which was prone to measurement error. However, questionnaires used in both cohorts were valid and had been widely used in population-based studies [12,13,14, 23]. Second, due to differences in cohort design and questionnaires used, the definition of MAFLD was slightly different in two cohorts, along with the healthy sleep score and diet quality. However, the specific definitions in each cohort were generally consistent with previous studies [1, 13, 23], and the results were materially unchanged, suggesting a solid association. Third, information on most of the Liver Essential 5 metrics was available only at baseline, thus we did not consider potential changes of lifestyle factors during the follow-up period. However, health behaviors could be influenced by disease status, which might lead to reverse causality. Fourth, Liver Essential 5 we created were derived from a sum of the number of healthy factors, assuming that these factors had identical effects on health outcomes, which might not be true. Therefore, we constructed a weighted score to account for different magnitudes, and a continuous score to address interindividual differences in sensitivity analyses, and found similar results. Fifth, our analyses might be potentially biased due to missing values on covariates. Multiple imputation has been used to impute the missing data assuming that they were missing at random. Given the fact that we cannot verify whether data were missing at random, we reported the results of complete data as our main results. Further comparison of the complete case analysis with imputation data added robustness to our findings. Sixth, the cross-sectional study design hindered causal inference, and future prospective studies were needed to validate our findings. Although we have carefully examined and selected covariates using a directed acyclic graph, residual confounding was still possible due to the nature of observational studies. However, the results remained basically the same in a series of sensitivity analyses, even after the adjustment for obesity. Additionally, considering that most observed relationships between lifestyle factors and risk of liver diseases rarely exceed a relative risk ratio of 3.00, the E value analysis suggested no major residual confounding factors in our study (Supplementary Table 8).

Future directions

Given the large proportion of individuals reclassified by Liver Essential 5 and the substantial reduction in MAFLD risk due to improvement in sleep quality, which is modifiable and therefore avoidable, future well-designed, strictly conducted, randomized clinical trials are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of adopting a more comprehensive lifestyle intervention on the management of MAFLD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, sleep quality shows the potential to provide additional risk stratification for MAFLD-related diseases on top of traditional HLS. Our findings support the need for urgent actions and reinforced efforts to adopt a more comprehensive lifestyle intervention regime for the prevention and treatment of MAFLD.

Responses