Astrocyte-to-neuron H2O2 signalling supports long-term memory formation in Drosophila and is impaired in an Alzheimer’s disease model

Main

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are distinctive among metabolites because of their physiological ambivalence1. On the one hand, ROS are toxic byproducts that can irreversibly oxidize macromolecules, and powerful scavenging enzymes are active to protect cells from ROS damage. The production of ROS is closely linked to the activity of the mitochondria in the production of ATP, and neurons are particularly susceptible to ROS damage due to their high energy requirements and high content of unsaturated fatty acids that are prone to peroxidation2. On the other hand, ROS play a positive role by activating signalling pathways involved in physiological functions such as cell survival, growth or response to stress1,2. ROS signalling occurs mainly through reversible oxidation of redox-sensitive cysteines, which requires a sharply regulated spatiotemporal increase in ROS concentration3. In vitro studies of long-term potentiation in mice have shown that neuronal ROS signalling plays a positive role in synaptic plasticity4,5. Recent in vivo studies in Drosophila have shown that ROS signalling is required during development for activity-dependent plasticity in motoneurons6,7. While pioneering studies have reported that mutant mice with altered ROS metabolism display learning or memory defects2,8, it remains unknown how ROS signalling is recruited in vivo for memory formation. Astrocytes are known to regulate neuronal redox homeostasis and cognition in mice9,10. In particular, it was shown that under physiological conditions mitochondrial ROS in astrocytes stimulate nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (NRF2) transcription factor expression, which promotes glutathione biosynthesis by astrocytes and antioxidant protection of neighbouring neurons10; however, it is not known whether neurons can trigger beneficial ROS production by astrocytes, and thereby if astrocytes are involved in the initiation of neuronal ROS signalling for synaptic plasticity.

Building a mechanistic view of ROS signalling during memory formation is essential not only from a brain physiology perspective, but it could also improve our understanding of the onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disease characterized in particular by memory loss and defects in redox homeostasis11,12. At the neuropathological level, AD is characterized by the progressive formation in the brain of amyloid plaques that correspond to the extracellular accumulation of amyloid β (Aβ) peptide, generated by cleavage of the transmembrane amyloid precursor protein (APP), and by the formation of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles consisting of hyperphosphorylated tau protein13. Early synaptic dysfunction has been associated with AD12,14, which correlates with cognitive decline15; however, the cascade of events leading to this fatal condition remains unclear.

Here, we have addressed these key brain physiology and pathology issues in Drosophila by combining brain H2O2 imaging using recently developed roGFP2-Tsa2ΔCR ultrasensitive sensors16 with functional characterization of ROS-related pathways during memory formation. We report that long-term memory (LTM) formation requires the establishment of a local H2O2 gradient in neurons of the olfactory memory centre, which follows the activation of ROS-producing enzymes in astrocytes. This signalling cascade is impaired by AD-related Aβ42. Our results provide a new framework to understand neuroglia interactions during memory formation in normal conditions and in AD.

Results

Astrocytes generate extracellular ROS for long-term memory

AD has been extensively linked to defects in redox homeostasis11,12. The objective of this study was to exploit the strengths of Drosophila genetics and in vivo imaging capabilities to further elucidate the relationships between Aβ, ROS and cognition; however, rather than artificially increasing ROS production and assessing its impact on memory formation, our approach was to investigate the potential beneficial effects of ROS on memory formation, with the understanding that this physiological pathway might be affected by Aβ in an AD-related model. Given the important role of neuron–glia metabolic coupling in Drosophila memory formation17,18,19, we sought to address these questions by investigating the potential role of astrocytes in neuronal ROS signalling.

We observed that inhibiting NADPH oxidase (Nox) expression in adult astrocytes impairs olfactory LTM in Drosophila (Fig. 1a). The only function of the transmembrane enzyme Nox is to produce extracellular O2•− from O2 and intracellular NADPH3, and therefore our observation was potentially important from a ROS signalling perspective. For this experiment, we used a well-established paradigm of associative aversive olfactory conditioning20,21 named spaced conditioning (Methods), along with inducible and spatially controlled expression of a Nox-targeting RNAi. A single Nox enzyme exists in Drosophila, which shows strong sequence similarity with the human Nox5 (ref. 22). Similarly to Nox5 (ref. 3), Drosophila Nox is activable by Ca2+ thanks to intracellular EF-hands domains that bind Ca2+(ref. 23).

a, Nox knockdown (KD) in adult astrocytes impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 11 (first group), n = 12 (second group), n = 15 (third group); F2,35 = 17.43, P = 0.000006). b, G6PD KD in adult astrocytes impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 13 (first and second groups), n = 18 (third group); F2,41 = 12.98, P = 0.00004). c, The fluorescent calcium sensor GCaMP6f was expressed in adult astrocytes. Nicotine stimulation (50 µM) elicited calcium increase in astrocytes, which was significantly decreased in nAChRα7 KD (n = 13 (first group), n = 11 (second group), t22 = 3.15, P = 0.005). d, nAChRα7 KD in adult astrocytes impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 10 (first and second groups), n = 14 (third group); F2,31 = 7.81, P = 0.002). e, Sod3 KD in adult astrocytes impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 12 (first and second groups), n = 15 (third group); F2,36 = 16.02, P = 0.00001). f, Scheme of the molecular actors involved in astrocytes for LTM. Nox, activated by calcium entry through nAChRa7, produces superoxide O2•− from O2 using the NADPH co-factor derived from the PPP. Extracellular O2•− is converted to H2O2 by extracellular Sod3 secreted from the astrocytes. Ru5P, ribulose-5-phosphate. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Genotype sample sizes are listed in the legend in order of bar appearance. Significance level of a two-sided t-test or the least significant Tukey pairwise comparisons following one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Source data

LTM formation requiring Nox activity in astrocytes depends on de novo protein synthesis21 in neurons of the olfactory memory centre, the mushroom body (MB)24,25. Conversely, anaesthesia-resistant memory (ARM), which forms after massed conditioning (Methods) and does not depend on de novo protein synthesis21, was not affected by Nox knockdown in adult astrocytes (Extended Data Fig. 1a). In addition, Nox knockdown did not affect perception of the stimuli used for conditioning (Supplementary Table 1), and LTM was normal when Nox RNAi expression was not induced (Extended Data Fig. 1a). To further ensure the specificity of Nox implication in LTM, we measured the immediate memory capacity after spaced conditioning of flies expressing Nox RNAi in adult astrocytes. Our results demonstrated that Nox knockdown did not affect immediate memory, confirming that superoxide production by astrocytes is required specifically for LTM, as measured at 24 h after spaced conditioning (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Last, we confirmed the involvement of Nox in adult astrocytes for LTM with a second nonoverlapping Nox RNAi (Extended Data Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1). These controls were performed in a systematic manner throughout the course of this study. With regard to text simplification, knockdown flies exhibiting the aforementioned phenotypes (impaired LTM as measured at 24 h after conditioning, assessed with two RNAis; normal ARM as measured at 24 h after massed conditioning; normal immediate memory after spaced conditioning; normal stimuli perception; normal LTM in the absence of RNAi induction) will be simply reported as displaying a specific LTM defect.

The Nox substrate NADPH is mainly produced by the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)26. To study this pathway we inhibited in adult astrocytes the expression of G6PD, the enzyme catalysing the first step of the PPP26, and we observed a specific LTM defect (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1d,e and Supplementary Table 1). Given that the PPP generates many intermediates involved in various biosynthetic processes, including fatty acids and nucleotides26, an additional experiment was conducted to ensure that inhibiting the PPP in astrocytes did not affect different forms of olfactory memory in an unspecific manner. Thus, in addition to the assessment of ARM following massed conditioning and immediate memory following spaced conditioning, the middle-term memory capacity following a single conditioning cycle was evaluated after G6PD knockdown in adult astrocytes. G6PD knockdown flies displayed normal middle-term memory (Extended Data Fig. 1d). The essential role of astrocytic PPP in LTM formation was confirmed by inhibiting the expression in astrocytes of Pgd and Pgls26, two other enzymes in this pathway (Extended Data Fig. 1e–g and Supplementary Table 1). Altogether, these results support the notion that astrocytic Nox generates O2•− required for LTM formation.

As stated above, similar to the human Nox5, Drosophila Nox is activated by Ca2+. Acetylcholine (ACh) is the major excitatory neurotransmitter of Drosophila brain neurons, and in particular MB neurons are cholinergic27. Among the ionotropic cholinergic receptors, the channel formed of nAChRα7 subunits is the most permeable to Ca2+(ref. 28) and is expressed in human astrocytes29. To examine whether nAChRα7 cholinergic stimulation induces a Ca2+ flux in Drosophila astrocytes, we expressed the GCaMP6f Ca2+ fluorescent reporter in astrocytes and stimulated the brains of live flies with nicotine, an nAChRα7 agonist. Nicotine stimulation induced an increased astrocytic Ca2+ concentration in control flies (Fig. 1c). This effect was dampened when nAChRα7 expression was inhibited in astrocytes (Fig. 1c). We next addressed the role of astrocytic nAChRα7 in memory and showed that nAchRα7 knockdown in adult astrocytes specifically impaired LTM (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Figs. 1b and 2a,b and Supplementary Table 1). These results suggest that during spaced conditioning ACh release can activate Ca2+ signalling in astrocytes through nAChRα7 and is required for LTM. Consistent with our findings, astrocytic nAChRα7 was implicated in the persistence of fear memory in mice30.

While O2•− is a highly reactive and therefore toxic ROS with a short half-life, H2O2, which is less reactive and has a longer half-life, is more suitable for ROS signalling1,31. Astrocytic Nox activity at the plasma membrane produces extracellular O2•−, whose conversion into H2O2 is catalysed by the only secreted superoxide dismutase (Sod), Sod3 (ref. 32). In the Drosophila brain, Sod3 is more strongly expressed in astrocytes than in neurons, as shown by single-cell transcriptomics data33 (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Sod3 knockdown in adult astrocytes specifically impaired LTM (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Figs. 1b and 2d,e and Supplementary Table 1). Altogether, these results suggest that a nAChRα7–Nox–Sod3 signalling cascade takes place upon LTM formation, which is triggered by ACh stimulation of astrocytes, resulting in extracellular H2O2 formation (Fig. 1f).

Like the tripartite synapse in the mammalian brain34, astrocytic processes overlap with synapses in the Drosophila brain35. We therefore wondered whether astrocytes might be a source of beneficial ROS imported by neurons during LTM formation. In particular, is H2O2 signalling involved during LTM formation in the MB?

An H2O2 gradient in MB α lobe supports LTM formation

The MB is a bilateral structure consisting of about 2,000 cholinergic neurons27 in each brain hemisphere. Axons of the MB neurons form bundles and branch out, giving shape to anatomical structures called lobes that synapse with the MB output neurons. MB neurons are classified into three different subtypes: the α/β neurons, whose axons branch to form an α vertical projection and a medial β projection (Fig. 2a); the α′/β′ neurons; and the γ neurons, which form a single medial γ lobe. The axonal projection of the α lobe is specifically involved in LTM formation20,36. We aimed to image H2O2 in MB neurons upon LTM formation. Recently, the ability to observe physiological H2O2 levels has become possible with the development of an ultrasensitive H2O2 fluorescent sensor, roGFP2-Tsa2ΔCR16, which we imported and characterized in Drosophila (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 3a).

a, Illustration of MB structure. Axons of MB neurons follow a branching pattern that forms vertical lobes (α and α′) and medial lobes (β, β′ and γ). b, Images of the roGFP2-Tsa2ΔCR H2O2 sensor expressed in MB neurons. 3D reconstructions of image stacks (128-µm-thick stack, 1 µm Z-step) of the H2O2 sensor in MB neurons at the two excitation wavelengths (988 and 780 nm) (top). Cb, cell bodies; vl, vertical lobes (α and α′); ml, medial lobes (β, β′ and γ). Horizontal plane with regions of interest, cell bodies and α vertical lobes delimited with dashed lines (bottom). Scale bar, 30 µm. c, The H2O2 level in α lobes normalized to the cell bodies value is increased upon spaced training, in comparison to the non-associative unpaired control (n = 13 (first group), n = 14 (second group); t25 = 2.82, P = 0.009). d, The H2O2 level in β or γ lobes normalized to the H2O2 level in cell bodies after spaced training was similar to the unpaired control (β, n = 9 (first group), n = 11 (second group), t18 = 0.94, P = 0.36; γ, n = 10 (first group), n = 9 (second group), t17 = 1.30, P = 0.21). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Genotype sample sizes are listed in the legend in order of bar appearance. Significance level of a two-sided t-test. **P < 0.01; NS, not significant, P > 0.05.

Source data

To observe change in H2O2 dynamics, flies expressing the H2O2 sensor in the MB were imaged between 0.5 h and 2 h after spaced conditioning, a time window when early LTM-encoding events occur17,37. Control flies were submitted to non-associative unpaired protocol that does not allow memory formation. Notably, in flies trained for LTM, we observed an increased H2O2 level in the MB α lobe (Fig. 2c), and no increase in the MB β and γ medial lobes (Fig. 2d). An additional point must be considered to interpret the H2O2 imaging data. As we previously demonstrated, Drosophila LTM formation involves activation of the PPP in MB neurons, fuelled by Glut1-mediated glucose import17. As PPP activity generates the reducing agent NADPH, its activation in the MB is expected to result in a global decrease in ROS concentration (compare with scheme in Extended Data Fig. 3b). Indeed, detailed examination of imaging data revealed a decreased H2O2 level in MB cell bodies in flies trained for LTM (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Notably, when glucose import was impaired in adult MB, the decreased H2O2 response in MB neuron cell bodies after spaced conditioning was abolished, but the H2O2 increase was observed in the α lobe (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Altogether, these data reveal the existence in LTM-forming flies of an H2O2 gradient within the MB neurons, generated by H2O2 influx within the α vertical lobe. These results are in agreement with the fact that the α lobe is specifically involved in LTM formation20,36.

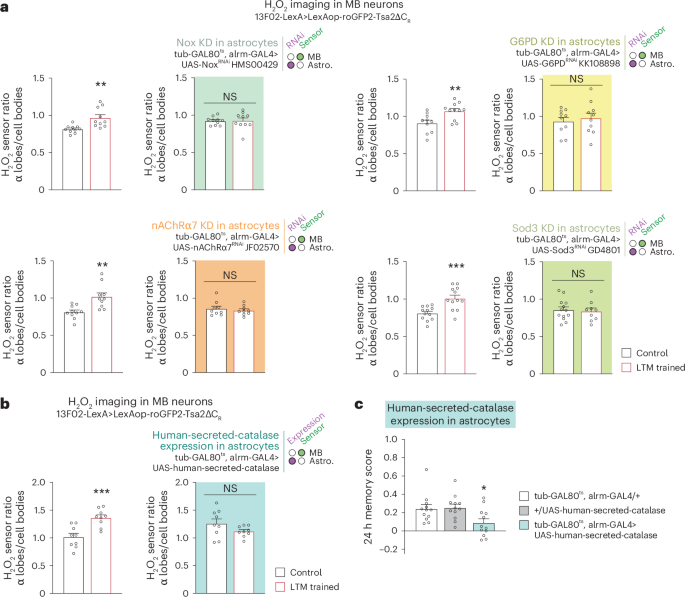

To test whether astrocyte activity modulates H2O2 signalling in the MB LTM centre, we imaged H2O2 in MB neurons while interfering with the H2O2-producing cascade in astrocytes. The increased level of H2O2 in the MB α lobe was lost by inhibiting the expression of either Nox, nAChRα7, G6PD or Sod3 in adult astrocytes (Fig. 3a). These results indicate that the H2O2 gradient formed in MB neurons after spaced conditioning originates from astrocytic Nox and Sod3 activity in response to ACh stimulation. To substantiate this hypothesis, we intended to deplete the extracellular H2O2 generated by astrocytic Sod3 during LTM formation by expressing a secreted form of the human catalase in astrocytes7. Catalase is responsible for catalysing the breakdown of H2O2 into H2O and O2. Notably, the typical increase in H2O2 observed in the α lobe following spaced conditioning was absent in the presence of the secreted catalase (Fig. 3b). In accordance with the imaging data, the LTM of flies that expressed the secreted catalase was found to be specifically impaired (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 3e and Supplementary Data Table 2). These findings substantiate the hypothesis that the H2O2 gradient observed in the MB during LTM formation is due to extracellular SOD3 activity.

a, Measurements of H2O2 levels in MB neurons after spaced training in the context of astrocytic KDs. The increase in the α lobes/cell bodies H2O2 level elicited by spaced training was impaired in KD of Nox (n = 10, t18 = 0.11, P = 0.91; wild-type control: n = 10, t18 = 3.47, P = 0.003), G6PD (n = 10 (first and second groups), t18 = 0.49, P = 0.63; wild-type control: n = 10 (first group), n = 11 (second group), t19 = 3.01, P = 0.007), nAChRα7 (n = 9, t16 = 0.63, P = 0.54; wild-type control: n = 10, t18 = 3.57, P = 0.002) and Sod3 (n = 13 (first group), n = 9 (second group), t20 = 0.33, P = 0.75; wild-type control: n = 12, t22 = 3.93, P = 0.0007). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. b, Expression of human-secreted-catalase in astrocytes abolished the increase in the α lobes/cell bodies H2O2 level elicited by spaced training (n = 9, t16 = 1.596, P = 0.13; wild-type control: n = 9, t16 = 4.136, P = 0.0008). c, Expression of human-secreted-catalase in astrocytes impaired 24 h memory after spaced conditioning (n = 12, F(2,33) = 4.603, P = 0.017). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Genotype sample sizes are listed in the legend in order of bar appearance. Significance level of two-sided t-test or the least significant Tukey pairwise comparison following one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant, P > 0.05.

Source data

A redox relay cascade is required in MB for LTM formation

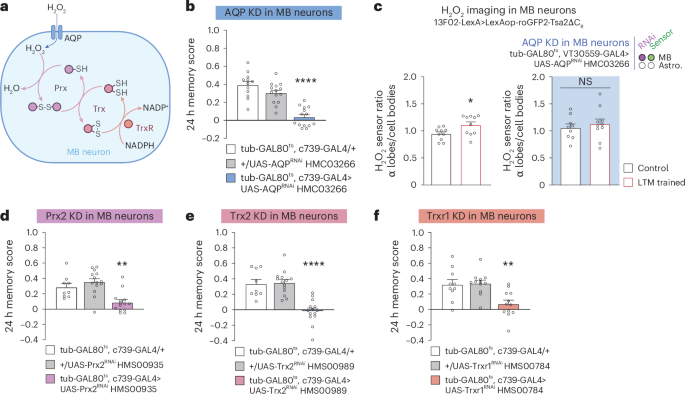

How does H2O2 produced extracellularly by astrocytic enzymes enter MB neurons upon LTM formation? Although H2O2 can diffuse across the plasma membrane, H2O2 import is strongly facilitated by channels of the aquaporin protein family38. We tested the potential involvement of the main Drosophila aquaporin, AQP, in LTM (Fig. 4a). AQP knockdown in adult MB α/β neurons specifically impaired LTM (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Table 3). The LTM defect following AQP knockdown was linked to a loss of the H2O2 increase in the α lobe after spaced conditioning (Fig. 4c). Three additional aquaporin orthologues have been identified in Drosophila: drip, bib and prip7. The inhibition of their expression in adult α/β MB neurons did not affect LTM (Extended Data Fig. 4c–h), indicating that AQP plays a specific role in H2O2 import following SOD3 activity.

a, Putative redox relay cascade downstream of H2O2 import in MB neurons. b, AQP KD in adult α/β MB neurons impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 12 (first group), n = 14 (second and third groups), F2,37 = 31.24, P = 0.00000001). c, The increase in H2O2 level in α lobes/cell bodies elicited by spaced training (n = 10, t18 = 2.42, P = 0.0261) was impaired in AQP KD in adult MB neurons (n = 9 (first group), n = 10 (second group), t17 = 0.59, P = 0.56). d, Prx2 KD in adult α/β MB neurons impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 9 (first group), n = 14 (second and third groups), F2,34 = 12.08, P = 0.0001). e, Trx2 KD in adult α/β MB neurons impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 9 (first group), n = 14 (second and third groups), F2,37 = 14.43, P = 0.0000007). f, Trxr1 KD in adult α/β MB neurons impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 10 (first group), n = 12 (second and third groups), F2,27 = 20.30, P = 0.0012). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Genotype sample sizes are listed in the legend in order of bar appearance. Significance level of a two-sided t-test or the least significant Tukey pairwise comparison following one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant, P > 0.05.

Source data

Our results support the idea that H2O2 signalling in α/β neurons occurs for LTM formation. H2O2 signalling is primarily characterized by the reversible oxidation of target cysteines on signalling proteins, which subsequently modifies their activity. This is achieved either by direct action of H2O2 following an increase in local concentration, or through a cascade of redox-sensitive relay enzymes, starting with the Cys-based peroxidase peroxiredoxin (Prx), an H2O2 scavenger (Fig. 4a)39,40. We identified Prx2 as the major Prx involved in LTM formation (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 5a–c and Supplementary Table 4). Oxidized Prx are reduced by thioredoxin (Trx)40, and we showed that Drosophila Trx2 is specifically involved in LTM (Fig. 4e, Extended Data Fig. 5b,d,e and Supplementary Table 4). Last, Trx is reduced by a Trx reductase (Trxr) that oxidizes NADPH into NADP+ in the process. We identified Trxr1 as a major actor of LTM formation in α/β neurons (Fig. 4f, Extended Data Figs. 5b and 6a,b and Supplementary Table 4). Prx H2O2 scavenging enzymes are involved in the general maintenance of redox homeostasis39,40. Consequently, the inhibition of Prx2 expression may potentially impact α/β MB neurons in an unspecific manner. To eliminate this possibility, we conducted an additional experiment, measuring middle-term memory after a single conditioning cycle of Prx2, Trx2 or Trxr1 knockdowns. This control is of particular significance given that middle-term memory is encoded by α/β neurons, as is LTM41. Knocking down Prx2, Trx2 or Trxr1 in α/β neurons did not affect middle-term memory, demonstrating the specificity of the effect on LTM (Extended Data Figs. 5a,d and 6a).

Altogether, these results reveal a cascade of redox-sensitive enzymes required for LTM formation in α/β MB neurons. This cascade could be involved in the regulation of gene expression required for LTM formation1,21.

Appl delivers extracellular copper for SOD3 activity

We have shown that H2O2 is generated extracellularly by Sod3, which requires extracellular Cu2+ for its catalytic activity32. Because of its potential toxicity, free Cu2+ is maintained at a very low concentration in cells and tissues by copper-binding proteins42. This raises the question of how sufficient Cu2+ levels can be accumulated at the MB synapses to sustain during LTM formation the activity of Sod3 secreted by astrocytes. We hypothesized that Appl, the single fly orthologue of APP transmembrane protein, might provide Cu2+ for astrocyte-derived Sod3 activity based on the following observations: (1) the APP extracellular domain has several Cu2+ binding sites43,44 whose function remains poorly understood45, and Drosophila Appl carries in its conserved E2 ectodomain the four histidines that are characteristic of the M1 high-affinity Cu2+ binding site46; (2) APP enables intracellular copper to be transported out of neurons, as APP overexpression decreases Cu2+ content in neurons in vitro, whereas APP loss of function leads to copper accumulation47; (3) Appl knockdown in MB neurons induces an LTM defect48; and (4) Appl exhibits neuronal expression and is enriched in α/β MB neurons49, which are involved in LTM20,36. We confirmed this strong α/β neuron expression with an HA-tagged Appl line generated by CRISPR (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 7a). Furthermore, we showed that knocking down Appl specifically in α/β neurons with RNAi expression induces an LTM defect (Fig. 5b, Extended Data Fig. 7b,c and Supplementary Table 5).

a, Image (maximum intensity projection of 22-µm-thick Z-stack acquisition, Z-step 1 µm) of C-terminal HA-tagged Appl immunostaining showing the high expression of HA-tagged Appl in α/β MB neurons (green). Scale bar, 40 µm. b, Appl KD in adult α/β neurons impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 12 (first group), 18 (second and third groups), F2,45 = 15.58, P = 0.000007). c, The increase in H2O2 level in α lobes/cell bodies elicited by spaced training (n = 15 (first group), n = 16 (second group), t29 = 4.30, P = 0.0002) was impaired in Appl KD in adult MB neurons (n = 15, t28 = 0.88, P = 0.39). d, Mild decreases in both Appl and Sod3 expression in MB neurons and astrocytes impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 12, F4,55 = 13.22, P = 0.0000001). This mild decrease was obtained by activating RNAi expression for 1 day instead of 3 days. e, Mild decrease in both Appl and Sod3 expression in MB neurons and astrocytes prevents increase in H2O2 level elicited by spaced training (wild-type control: n = 10, t18 = 3.741, P = 0.0015; Sod3 KD: n = 10, t18 = 2.651, P = 0.0163; Appl KD: n = 10, t18 = 2.655, P = 0.0161; Sod3 and Appl KD: n = 10, t18 = 1.262, P = 0.2229). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Genotype sample sizes are listed in the legend in order of bar appearance. Significance level of a two-sided t-test or the least significant pairwise Tukey comparison following one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant, P > 0.05.

Source data

If Appl does provide copper to Sod3, the H2O2 gradient that forms after spaced conditioning should require Appl. Indeed, we observed that the H2O2 gradient after spaced conditioning was abolished when Appl expression was inhibited in adult MB (Fig. 5c).

To further support the idea that Appl and Sod3 are involved in the same pathway, we searched for a synergistic interaction between Appl and Sod3 using mild inhibition of their expression. The objective was to demonstrate that the concomitant reduction in Appl and Sod3 expression could result in a more pronounced LTM impairment than that observed in single knockdowns. The flexibility of the GAL4/GAL80ts system, which is induced by elevated temperature, was used to express Appl RNAi for a brief period of 1 day, instead of the usual 3 days of RNAi expression. At the behavioural level, the induction of Appl or Sod3 RNAi for a single day in MB neurons and astrocytes did not result in an LTM impairment (Fig. 5d). Next, we asked whether the brief simultaneous induction of Appl and Sod3 RNAi would affect LTM, thus revealing a synergistic interaction. Strikingly, LTM was specifically abolished when both Appl and Sod3 expressions were inhibited in MB neurons and astrocytes for one day (Fig. 5d, Extended Data Fig. 7d and Supplementary Table 5). Of note, the simultaneous mild inhibition of Appl and Sod3 expressions in MB alone or astrocytes alone did not impact LTM (Extended Data Fig. 7e,f). Altogether, we can conclude that the inability to form LTM in double-knockdown flies results from the simultaneous mild decrease of Appl expression in the MB, and of Sod3 expression in astrocytes. To further substantiate this finding, we conducted imaging of H2O2 dynamics in the double knockdown following brief RNAi expression. Formation of the H2O2 gradient after spaced conditioning was abolished in flies expressing both Appl and Sod3 RNAi, whereas it remained unaltered in flies expressing a single RNAi, aligning with the behavioural data (Fig. 5e). These results outline the existence of a strong functional interaction between Appl and Sod3, and are in agreement with the hypothesis that Appl supplies copper for Sod3 activity during LTM formation.

To clarify the involvement of the Appl–Sod3 interaction in the early phase of LTM formation rather than in memory recall, which occurs 24 h after conditioning in our experiments, we examined the performance of flies in which the brief Appl and Sod3 RNAi expression was initiated immediately following spaced training, as opposed to before training. The memory performance of flies expressing both Appl and Sod3 RNAi for 1 day after training was not affected (Extended Data Fig. 7g), whereas control flies expressing both RNAi for 1 day before training exhibited an LTM defect (Extended Data Fig. 7g). These results lend support to the hypothesis that Appl–Sod3 interaction is involved in an early step of LTM formation, rather than in LTM recall.

APP physiological function has been linked to many pathways50,51. To further demonstrate that the LTM defect of the Appl knockdown is indeed due to a lack of copper, we aimed to rescue the LTM defect of the Appl mutant by feeding flies with copper-complemented food. Notably, the memory performance of the Appl knockdown was fully rescued by 1 mM copper feeding before conditioning (Fig. 6a). In agreement with this, the H2O2 gradient was restored after spaced conditioning in the Appl knockdown supplemented with copper (Fig. 6b). Thus, copper-supplemented food can compensate for Appl knockdown at both the behavioural and H2O2 signalling levels. Altogether, these results strongly support the idea that the main function of Appl during LTM formation in MB α lobe20,36 is to deliver extracellular copper for Sod3.

a, Copper feeding (1 mM) 24 h before spaced training restored normal memory capacity in flies with an Appl KD in adult α/β MB neurons (two-way ANOVA, n = 14, copper treatment: F1,78 = 0.94, P = 0.33; genotype: F2,78 = 4.48, P = 0.01; interaction: F2,78 = 6.70, P = 0.002). b, Copper feeding (1 mM) 24 h before training restored the H2O2 level in α lobes/cell bodies in MB neuron presynaptic terminals of an Appl KD in adult MB neurons (right) (two-way ANOVA, n = 11, copper treatment: F1,40 = 3.07, P = 0.087; training: F1,40 = 0.92, P = 0.34; interaction: F1,40 = 7.01, P = 0.012). In wild-type controls (left), the increase in H2O2 level in the α lobes/cell bodies elicited by spaced training was not affected by copper feeding (two-way ANOVA, n = 11 (first, third and fourth groups), n = 12 (second group), copper treatment: F1,43 = 0.71, P = 0.40; training: F1,43 = 15.32, P = 0,0003; interaction: F1,43 = 0.30, P = 0.59). c, Appl expression is increased in MB α lobes after spaced training. Control flies received odorant and shock stimuli temporally dissociated, a condition that does not induce LTM (α lobes: n = 20, t38 = 2.181, P = 0.0355; β lobes: n = 20, t38 = 0.5444, P = 5894). d, Mutations of copper-binding histidines H(535) and H(539) affect memory after spaced training (n = 30, t58 = 4.169, P = 0.0001). e, Copper feeding (2 mM) 24 h before spaced training restored normal memory capacity in ApplH(535),H(539) flies (two-way ANOVA, n = 18, copper treatment: F1,68 = 5.603, P = 0.0208; genotype: F1,68 = 17.22, P = 0.00009; interaction: F1,68 = 4.932, P = 0.0297). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Genotype sample sizes are listed in the legend in order of bar appearance. Significance level of a two-sided t-test or the least significant Tukey pairwise comparison following one-way ANOVA or Šidák pairwise comparison following two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant, P > 0.05.

Source data

This leads to the question of why the increase in H2O2 occurs only in the α lobe of the MB, rather than in both the α and β lobes, which are two axonal projections of the same MB neurons. We postulated that this may be due to the activity of Appl itself, given that its copper-delivering property is permissive for H2O2 production by Sod3. The expression of Appl was monitored in the α and β lobes following spaced conditioning using the Appl-HA line and anti-HA immunohistochemistry. The level of Appl-HA expression was normalized to that of green fluorescent protein (GFP), which was expressed homogeneously in MB α/β neurons using the GAL4/UAS system. Notably, Appl-HA expression was specifically elevated in the α lobe following spaced conditioning, whereas no increase was observed in the β lobe (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, no increase in Appl-HA was observed in the α lobe following massed conditioning, a condition that does not engage H2O2 signalling in α/β neurons (Extended Data Fig. 8a). These findings support the notion that an elevation in Appl-HA levels within the α lobe results in an augmentation of copper release in the surrounding area, thereby facilitating the localized activation of Sod3 secreted by astrocytes.

To further illustrate the pivotal function of the E2 copper-binding domain of Appl in LTM, we generated via CRISPR a constitutive Appl mutant for histidines of the evolutionarily conserved E2 copper-binding domain. E2 histidines at positions 535 and 539 were replaced by arginines (Methods). It should be noted that these mutations were introduced into the Appl gene at its typical chromosomal location, without affecting regulatory sequences. ApplH(535)R,H(539)R mutant with modified copper-binding histidines exhibited an impairment in LTM (Fig. 6d). ARM and middle-term memory remained unaltered in ApplH(535)R,H(539)R flies (Extended Data Fig. 8b), whereas middle-term memory is affected in Appl knockdown52. The olfactory acuity and shock reactivity of the ApplH(535)R,H(539)R mutant were normal (Supplementary Table 6). Notably, the memory defect of ApplH(535)R,H(539)R mutant was rescued by 24 h 2 mM copper feeding (Fig. 6e). These findings further substantiate the pivotal and specific role of the copper-binding property of Appl in LTM formation.

Aβ42 inhibits astrocytic nAChRα7 and prevents H2O2 signalling

Following the observation that Appl is involved in the activation of H2O2 signalling, we wondered whether, conversely, the toxic derivative of APP, amyloid β (Aβ), can inhibit this signalling pathway. Notably, human Aβ42 is a strong ligand for the nAChRα7 cholinergic receptor53. At very low concentrations (<100 pM), which we cannot generate in Drosophila using available genetic expression systems, oligomeric Aβ42 was previously shown in vitro to activate nAChRα7 (ref. 54); however, in the 10–100 nM range, Aβ42 becomes a strong inhibitor of nAChRα7, preventing activation of the receptor by its natural ligand, ACh55. As we showed here that nAChRα7 activation in astrocytes initiates an H2O2 signalling pathway, we postulated that secreted Aβ might impede this process. Because Appl shows no clear sequence similarity with APP at the level of the Aβ sequence56, we expressed a secreted form of the human Aβ42 peptide, as frequently performed in Drosophila to study the consequences of brain amyloid expression57,58. The human Aβ42 peptide was expressed with a signal sequence that ensures its secretion into the extracellular space56. After several days of constitutive human Aβ42 expression in the Drosophila brain, diffuse aggregates are observed, along with neurodegenerative defects57. These defects are not observed after 3 days of Aβ42 induction57. As we aimed to evaluate the potential acute effect of Aβ42 on astrocytic nAChRα7, expression was activated in MB α/β neurons for a short 24-h period. We observed that the calcium response to nicotine was inhibited in the presence of Aβ42 (Fig. 7a), suggesting that human Aβ42 secreted by MB neurons inhibits astrocytic nAChRα7. We then showed that expressing Aβ42 in MB for 24 h affected LTM specifically (Fig. 7b, Extended Data Fig. 9a and Supplementary Table 7). Last, we showed that Aβ42 inhibits formation of the H2O2 gradient in MB neurons upon spaced conditioning (Fig. 7c). These results demonstrate that an acute expression of toxic Aβ42 in young flies prevents H2O2 formation by astrocytes after spaced conditioning, and therefore LTM formation.

a, Nicotine stimulation (50 µM) elicited increased calcium in astrocytes, which was significantly decreased when secreted human Aβ42 was expressed by MB neurons (n = 10, t18 = 2.29, P = 0.03). b, Human Aβ42 secretion by adult α/β neurons impaired memory after spaced conditioning (n = 12, F2,33 = 18.51, P = 0.000004). c, Spaced training elicited an increase in the H2O2 level of the α lobes/cell bodies as compared with the unpaired control (n = 9, t16 = 2.75, P = 0.014), which was impaired by human Aβ42 secretion by adult MB neurons (n = 9 (first group), n = 8 (second group), t15 = 0.72, P = 0.48). d, Model of ANHOS for LTM formation. Ach release from MB neurons27 upon spaced training activates astrocytic nicotinic receptor nAChRα7, which induces a calcium elevation in astrocytes, resulting in Nox activation. Nox produces extracellular O2•− in the presence of NADPH co-factor derived from astrocytic PPP. In the presence of Cu2+ delivered by MB neuronal Appl, extracellular astrocytic Sod3 converts O2•− to H2O2. H2O2 enters MB neuron lobes through the AQP channel and fuels the redox-sensitive cascade composed of Prx2, Trx2 and Trxr1 enzymes. Regeneration of reduced forms of these enzymes is provided by PPP-derived NADPH produced during LTM formation17. Oxidized Prx2 and Trx2 can activate signalling cascades (to be identified), which allows LTM formation. In a parallel pathway, H2O2 can directly oxidize signalling proteins (dotted line). Aβ42 impedes ANHOS by inhibiting nAChRα7. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Genotype sample sizes are listed in the legend in order of bar appearance. Significance level of a two-sided t-test or the least significant Tukey pairwise comparison following one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; NS, not significant, P > 0.05.

Source data

Discussion

ROS are byproducts produced mainly by mitochondria, and they are particularly toxic for neurons2. It has been suggested that ROS play a negative role in normal cognitive aging59, and that a defect in redox homeostasis is involved in the memory impairment that is characteristic of AD59,60. Glia help neurons fighting oxidative stress in various ways, including the production of reductive glutathione10,61,62 or accumulation of peroxidated lipids transferred from neurons63; however, ROS also play physiological roles1, and modulating the level of enzymes involved in ROS metabolism affects synaptic plasticity2 and learning and memory8,10. Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms controlling ROS signalling during memory formation have remained poorly known, in particular because imaging physiological ROS variations during memory formation was out of reach until the development of a genetically encoded highly sensitive sensor16. Moreover, it was not known if glia could transfer beneficial ROS to neurons for neuronal plasticity and memory formation. Our data now provide a mechanistic understanding of the role of H2O2 signalling in vivo during memory formation. We have deciphered a pathway by which astrocytes deliver beneficial H2O2 to neurons for LTM formation, a phenomenon we have named astrocyte-to-neuron H2O2 signalling (ANHOS) (Fig. 7d). The production of ROS by astrocytic Nox and Sod3 enzymes, which follows ACh neurotransmitter-induced Ca2+ increase, ensures a local H2O2 accumulation in the MB α lobe, the specific axonal projections encoding LTM20,36. Following H2O2 import, a signalling cascade is initiated by redox-sensitive enzymes64 comprising Prx2, Trx2 and Trxr1 (Fig. 7d). We put forth the proposition that this cascade serves as a trigger for LTM formation through the reversible oxidation of specific cysteines in LTM-relevant signalling proteins, in conjunction with the potential direct action of H2O2 itself. Although the future investigation of these molecular changes will be important, assessing transient changes of oxidation states is technically challenging, and this will require targeting the small subpopulation of α/β neurons that respond to the odorant used during LTM conditioning65. What is the potential connection between ANHOS and cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB), a transcription factor that has been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in LTM formation in Drosophila and mice24,25? Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) have been demonstrated to activate CREB by phosphorylation, thereby facilitating memory consolidation66,67. Moreover, kinases of the MAPK family, such as p38a and ERK, can be activated by H2O2 signalling68,69. It is therefore proposed that the link between H2O2 signalling in the α lobe and the regulation of transcription by CREB may imply the activation of the MAPK pathway and retrograde signalling from the axonal projection to the nucleus.

Sod3 secreted by astrocytes plays a central role in ANHOS, as it generates the H2O2 molecules that will be imported by neurons. Sod3 requires a source of free copper for its catalytic activity. Although the free copper concentration remains extremely low in the brain because of its toxicity, copper concentrations around 100 µM have been reported at the synaptic cleft in mammals70. Our results in Drosophila suggest that an essential source of copper for the activity of Sod3 secreted by astrocytes comes from neuronal Appl, which exhibits an evolutionarily conserved copper-binding site on its extracellular domain. Indeed, Appl and Sod3 knockdowns display a strong synergistic interaction (Fig. 5d,e) and feeding copper to Appl knockdown flies rescued the LTM defect (Fig. 6a) and reestablished the H2O2 gradient in the olfactory memory centre (Fig. 6b). In addition, mutation of two of four evolutionarily conserved histidines within the E2 copper-binding domain of Appl resulted in impaired LTM (Fig. 6d), whereas middle-term memory remained unaltered (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Conversely, Appl knockdown affects both LTM and middle-term memory52, which further delineates the specific role of the copper-binding domain in LTM. The study of the Drosophila histidine E2 mutant is particularly important because, to the best of our knowledge, no mouse mutants for E2 copper-binding histidines have been reported so far. Feeding copper to Appl E2 mutant rescued the LTM defect (Fig. 6e), outlining the essential role of the copper-binding property of Appl in LTM formation.

Altogether, our results suggest that the copper-binding property of Appl and its functional interaction with Sod3 are the major roles of Appl in LTM formation48. Of note, expression of extracellular Sod3 in the human brain is much stronger in astrocytes than in neurons71, as in Drosophila33 (Extended Data Fig. 2c). In mammals, APP binds copper43,44; it is expressed at the presynaptic active zone of neurons, where neurotransmitters are released72,73; and it is involved in synaptic plasticity and memory51,74. We propose that our model developed in Drosophila (Fig. 7d) can be generalized to these mammalian data, leading us to conclude that APP activates astrocytic Sod3 for memory formation in mammals. In the mammalian brain, glutamate is the predominant excitatory neurotransmitter. The ANHOS cascade may be activated not only at the cholinergic synapse, but also at the glutamatergic synapse, following calcium signalling in astrocytes that results from the activity of glutamatergic neurons75.

From a pathological standpoint, our findings demonstrate that human Aβ42 exerts an inhibitory effect on the ANHOS cascade. This is evidenced by its capacity to impede the Ca2+ influx observed in astrocytes following nAChRα7 stimulation, as well as the H2O2 increase in the MB LTM centre subsequent to spaced conditioning. It is likely that the effect of Aβ42 involves the inhibition of nAChRα7 in astrocytes, which in turn prevents the formation of ROS by astrocytic Nox and Sod3. We propose that this inhibitory process is at play during AD initiation. Indeed, several observations are in agreement with the pathophysiological hypothesis that impairment of astrocytes by diffusible Aβ42 oligomers at cholinergic synapses may occur precociously in the AD brain: (1) soluble synaptic Aβ42 correlates better with the pattern of cognitive decline in AD than amyloid plaques15; (2) nAChRα7 is expressed by human brain astrocytes, in particular in the hippocampus29, a neural structure that plays a major role in episodic and spatial memory; (3) Aβ42 inhibits nAChRα7 in vitro at a nM concentration76; and (4) in humans, pathology of the basal forebrain cholinergic neurons precedes cortical defects but is predictive of future memory deficits77,78. In addition, as revealed in a global data-mining survey, Sod3 has been associated with AD in several ‘omics’ approaches, although its implication remains to be understood79. Our ANHOS model integrates observations of early AD and cholinergic neurons, and proposes a key role for Sod3 in AD. In normal conditions, cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain, which send diffuse projections to many cortical areas as well as the hippocampus, are involved in memory formation77,80. The transition from a physiological condition to an AD condition might therefore involve a switch from an ANHOS activation by ACh to ANHOS inhibition via increased Aβ42 production.

Methods

Experimental model

Flies (Drosophila melanogaster) were raised on standard medium (inactivated yeast 6% w/v; corn flour 6.7% w/v; agar 0.9% w/v; methyl-4-hydroxybenzoate 22 mM), at 18 or 23 °C (depending on the experiments; see respective details below) and 60% humidity in a 12-h light–dark cycle. The study was performed on 1–3-day-old adult flies. For behavioural experiments, both male and female flies were used. For imaging experiments, female flies were used because of their larger size. Before imaging or behavioural experiments, we chose flies informally in a random manner from a much larger group raised together for all studies; there was no formal randomization procedure for selecting flies. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Transgenic flies were outcrossed for five generations to a reference strain carrying the w1118 mutation in an otherwise Canton-Special genetic background. Because TRiP RNAi transgenes are labelled by a y+ marker, these lines were outcrossed to a y1 w67c23 strain in an otherwise Canton-Special background. All strains used in this study are described in Supplementary Table 8.

Behavioural experiments

For behavioural experiments, flies were raised on standard medium at 18 °C and 60% humidity in a 12-h light–dark cycle. We used the GAL4/GAL80ts TARGET system81 to inducibly express RNAi constructs exclusively in the MB or astrocytes of adult flies, and not during development. To achieve the induction of RNAi expression, adult flies were kept at 30.5 °C for 3 days before conditioning, unless otherwise specified. To induce Aβ42 carrying the pre-proenkephalin signal peptide for secretion58, adult flies were kept at 30.5 °C for 24 h before conditioning. To test the interaction of Appl and Sod3, adult flies were kept at 30.5 °C for 24 h to achieve mild expression of RNAis before conditioning (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 7g) or after conditioning (Extended Data Fig. 7g). Otherwise, for non-induced experiments, experimental flies were transferred before conditioning to fresh bottles at 18 °C.

All behavioural experiments, including the sample sizes, were conducted similarly to other studies from our laboratory17,20,37. Groups of 20–50 flies were subjected to one of the following olfactory conditioning protocols at 25 °C: a single training cycle (1×), five consecutive associative training cycles (5× massed training), or five associative cycles spaced by 15-min inter-trial intervals (5× spaced training). A non-associative control protocol (unpaired protocol) was also employed for imaging experiments and Appl-HA immunochemistry experiments, during which the odour and shock stimuli were delivered separately in time, with shocks occurring 3 min before the first odorant. Conditioning was performed using previously described barrel-type machines that allow the parallel training of up to six groups17,20,36. Throughout the conditioning protocol, each barrel was plugged into a constant air flow at 2 l min−1. For a single cycle of associative training, flies were first exposed to an odorant (the CS+) for 1 min, while 12 pulses of 5-s long 60-V electric shocks were delivered; flies were then exposed 45 s later to a second odorant without shocks (the CS-) for 1 min. The odorants 3-octanol (Fluka 74878, Sigma-Aldrich) and 4-methylcyclohexanol (Fluka 66360, Sigma-Aldrich), diluted in paraffin oil to a final concentration of 2.79 × 10−1 g l−1, were alternately used as conditioned stimuli. During unpaired conditionings, the odour and shock stimuli were delivered separately in time, with shocks occurring 3 min before the first odorant.

Flies were kept at 18 °C on standard medium between conditioning and the memory test, except in experiments in which immediate memory was tested after spaced conditioning. The memory test was performed in a T-maze apparatus82, 24 h after massed or spaced training, at 25 °C. The memory test was performed at 2 h after 1× training. Each arm of the T-maze was connected to a bottle containing 3-octanol and 4-methylcyclohexanol, diluted in paraffin oil to a final concentration identical to the one used for conditioning. Flies were given 1 min to choose between either arm of the T-maze. A performance score was calculated as the number of flies avoiding the conditioned odour minus the number of flies preferring the conditioned odour, divided by the total number of flies. A single performance index value is the average of two scores obtained from two groups of genotypically identical flies conditioned in two reciprocal experiments, using either odorant (3-octanol or 4-methylcyclohexanol) as the CS+. The indicated ‘n’ is the number of independent performance index values for each genotype. To avoid giving disproportionate statistical weight to a small number of flies, rare behavioural experiments involving a group of fewer than six flies were excluded.

The shock response tests were performed at 25 °C by placing flies in two connected compartments; electric shocks were provided in only one of the compartments. Flies were given 1 min to move freely in these compartments, after which they were trapped, collected and counted. The compartment where the electric shocks were delivered was alternated between two consecutive groups. Shock avoidance was calculated as for the memory test.

Because the delivery of electric shocks can modify olfactory acuity, our olfactory avoidance tests were performed on flies that had first been presented another odour paired with electric shocks. Innate odour avoidance was measured in a T-maze similar to those used for memory tests, in which one arm of the T-maze was connected to a bottle with odour diluted in paraffin oil and the other arm was connected to a bottle with paraffin oil only. Naive flies were given the choice between the two arms during 1 min. The odour-interlaced side was alternated for successively tested groups. Odour concentrations used in this assay were the same as for the memory assays. At these concentrations, both odorants are innately repulsive.

In vivo calcium imaging

Calcium imaging experiments were performed on flies expressing the GCaMP6f calcium sensor in astrocytes via the alrm-GAL4 driver, in combination with UAS-GCaMP6f. Transgenes were expressed in astrocytes using the inducible tub-GAL80ts; alrm-GAL4 driver. As carried out previously in our laboratory for imaging experiments17,37, flies were raised at 23 °C to increase the expression level of genetically encoded sensors without allowing RNAi expression. Adult flies were kept at 30.5 °C for 3 days before conditioning to achieve the induction of RNAi expression.

As in all previous imaging work from our laboratory, all in vivo imaging was performed on female flies, which are preferred as their larger size facilitates surgery. A single fly was picked and prepared for imaging as previously described17,37. In brief, the head capsule was opened and the brain was exposed by gently removing the superior tracheae. The head capsule was bathed in artificial haemolymph solution for the duration of the preparation. The composition of this solution was: NaCl 130 mM (Sigma, S9625), KCl 5 mM (Sigma, P3911), MgCl2 2 mM (Sigma, M9272), CaCl2 2 mM (Sigma, C3881), d-trehalose 5 mM (Sigma, 9531), sucrose 30 mM (Sigma, S9378) and HEPES hemisodium salt 5 mM (Sigma, H7637). At the end of surgery, any remaining solution was absorbed and a fresh 100-μl droplet of this solution was applied on top of the brain. Two-photon imaging was performed using a Leica TCS-SP5 upright microscope equipped with a ×25, 0.95 NA water-immersion objective. Two-photon excitation was achieved using a Mai Tai DeepSee laser tuned to 910 nm. The frame rate was one image per second. Recordings were acquired in the astrocytic region in the anterior part of the brain (where MB vertical lobes are located), at approximately 30 µm depth from the top of the brain. Calcium imaging experiments with nicotine stimulation were performed as previously described17. Nicotine was freshly diluted from a commercial liquid (Sigma, N3876) into the saline used for imaging on each experimental day. A perfusion setup at a flux of 2.5 ml min−1 enabled the time-restricted application of 50 μM nicotine on top of the brain17. Baseline recording was performed during 1 min, after which the saline supply was switched to drug supply. The solution reached the in vivo preparation within 30 s. The stimulation was maintained for 30 s, before switching back to the saline perfusion for an additional 5 min. The GCaMP6f intensity was measured in the anterior part of the brain where MB vertical lobes are located. GCaMP6f signal was calculated over time after background subtraction and normalized by a baseline value calculated over the 30 s preceding drug injection using MATLAB software (MathWorks).

In vivo H2O2 imaging

H2O2 imaging experiments were performed on flies expressing the excitation ratiometric H2O2 sensor roGFP2-Tsa2ΔCR16 in MB neurons via the 13F02-LexA driver, in combination with LexAop-roGFP2-Tsa2ΔCR (generated in this study). Transgenes were expressed in astrocytes using the inducible tub-GAL80ts; alrm-GAL4 driver, or in MB neurons using the inducible tub-GAL80ts; VT30559-GAL4 driver. For imaging experiments, flies were raised at 23 °C, except for the imaging experiment after brief RNAi expression for which flies were raised at 18 °C (Fig. 5e). Adult flies were kept at 30.5 °C for 3 days before conditioning to achieve the induction of RNAi expression. For experiments on conditioned flies, data were collected indiscriminately from 30 min to 2 h after training.

Surgery was performed as for calcium imaging. At the end of surgery, any remaining solution was absorbed and a fresh 100-μl droplet of saline solution was applied on top of the brain. Two-photon imaging was performed using a pulsed infra-red laser (Insight X3, Spectra Physics), coupled to a Leica SP8 Dive upright microscope equipped with a ×20, 1.0 NA water-immersion objective and non-descanned spectral hybrid detectors. Emission was collected from 500 to 570 nm.

To characterize the roGFP2-Tsa2ΔCR probe for two-photon excitation microscopy, excitation spectra were measured from 780 to 1,060 nm in steps of 8 nm. Oxidation of the probe was obtained by applying 2 mM H2O2 (final concentration) on top of the brain. Spectra in the basal and oxidized states were measured before and 15 min after H2O2 treatment, respectively. Excitation wavelengths of 780 nm and 988 nm were selected for further experiments, as they maximized the sensor emission ratio (ratio 780 nm to 988 nm) between the basal and oxidized states. Experiments after conditioning were performed as follows: on a given brain area, two z-stacks (one at each acquisition wavelength) were consecutively acquired with a step of 1 µm and a line averaging of 3. The detector gain was strictly similar between the two stacks and was set to the 988 nm excitation wavelength at the highest value to avoid any pixel saturation; however, because of differential signal strength within different cellular compartments of MB neurons, two sets of stacks were acquired for each brain: one encompassing the MB lobes, and one covering the soma and calyx area, with different detector gains. For data analysis, the average intensity of three consecutive planes of the stack was calculated for each region of interest at the two excitation wavelengths. Oxidation of the sensor by H2O2 was measured by the ratio of the signal collected upon 780 nm excitation over the signal collected upon 988 nm excitation (referred to as ‘H2O2 sensor ratio’), using Leica Microsystems software LAS X Small (offline version).

Dietary copper supplementation

Copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 197730010) was added to melted standard food medium to achieve a final concentration of 1 mM (Fig. 6a,b), a concentration that does not affect survival rate under chronic exposure83. Flies were kept on regular food medium for 48 h at 30.5 °C to achieve RNAi induction and then transferred to copper-enriched medium for 24 h at 30.5 °C for both behavioural and H2O2 imaging experiments. No lethality was observed with this copper feeding diet. Control flies were transferred on regular medium for 24 h at 30.5 °C.

For the copper rescue of ApplH(535),H(539) flies (Fig. 6e), copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate was added to melted standard food medium to achieve a final concentration of 2 mM. Flies were kept on copper-enriched medium for 24 h at 18 °C before spaced conditioning.

Immunohistochemistry

Before dissection, whole adult female flies (2–4 days old) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBST (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% Triton X-100) at 4 °C overnight. Brains were dissected in PBS solution and rinsed three times for 20 min in PBST, blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, A9085) in PBST for 2 h at room temperature, and then incubated with primary antibodies at 1:200 dilution (rat anti-HA, Roche, ROAHAHA 11867423001, clone 3F10) in the blocking buffer (2% BSA in PBST) at 4 °C overnight. The following day, brains were rinsed three times for 20 min in PBST, and incubated with secondary antibodies at 1:400 dilution (goat anti-rat Alexa 488, Invitrogen, A11006) in blocking buffer for 3 h at room temperature. Brains were rinsed for a further three times for 20 min in PBST and were mounted in ProLong Mounting Medium (Lifetechnology) for imaging. Images were acquired with a Nikon A1R confocal microscope with a ×20 objective.

In experiments where Appl-HA expression was quantified in MB neurons following spaced conditioning, artificial GFP expression was used as an expression control. Appl-HA/+; tub-GAL80ts/+; VT30559-GAL4>UAS-mCD8GFP females were raised at 18 °C and transferred for 1.5 days at 30.5 °C to induce GFP expression in MB neurons. The flies were trained using the various protocols. Two hours following conditioning, adult females were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBST (PBS containing 1% Triton X-100) at 4 °C overnight. For immunochemical analysis, brains were dissected in PBS solution and rinsed three times for 20 min in PBST. They were then blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, A9085) in PBST for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the samples were incubated with primary antibodies at a dilution of 1:200 dilution for rat anti-HA (Roche, ROAHAHA 11867423001, clone 3F10) and 1:400 dilution for mouse anti-GFP (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, DSHB-GFP-12A6, clone 12A6) in blocking buffer (2% BSA in PBST) at 4 °C overnight. On the subsequent day, the brains were rinsed three times for 20 min in PBST and incubated with secondary antibodies at a dilution of 1:400 (goat anti-rat Alexa 594, Invitrogen, A11007 and goat anti-mouse Alexa 488, Invitrogen, A11029) in blocking buffer for 3 h at room temperature, and subsequently placed at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, the brains were rinsed three times for 20 min in PBST and mounted in ProLong Mounting Medium (Life Technologies) for imaging. Images were obtained using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope with a ×20 objective.

Western blot

Proteins were extracted from adult female heads after liquid nitrogen snap freezing and mechanical grinding in lysis buffer containing sucrose 100 mM, KH2PO4/HPO4− 40 mM, EDTA 30 mM, KCl 50 mM, 0.25% Triton X-100, dithiothreitol 10 mM, PMSF 0.5 mM and 1× protease inhibitors (Roche, 11836153001). Protein extracts containing loading buffer NOVEX Tricine SDS sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, LC1676) were run in NOVEX 10–20% Tricine gels (Thermo Fisher, EC66252BOX) and then transferred on nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were saturated with 15% non-fat milk, PBS–Tween 0.2% for 1 h. Membranes were incubated with primary anti-HA antibodies diluted in PBS–Tween 0.2% blocking medium (mouse anti-HA, 1:5,000 dilution, BioLegend, 901513, clone 16B12) overnight at 4 °C under agitation. Membranes were rinsed five times for 8 min in PBS–Tween 0.2% and incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature under agitation (HRP anti-mouse, 1:10,000 dilution, Promega, W4021). Membranes were further rinsed five times for 8 min in PBS–Tween 0.2%. Revelation was conducted using NOVEX ECL substrate (Thermo Fisher, WP20005) and chemiluminescence was detected with ImageQuant LAS4000. The same procedure was then applied to the same membranes with anti-tubulin antibodies (mouse anti-tubulin, 1:40,000 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich, T16199, clone DM1A). The molecular weight ladder corresponds to Invitrogen SeeBlue Plus2 (LC5925).

Quantitative PCR

The efficiency of the knockdowns (KDs) used in this study was validated by quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (RT–qPCR) to measure the messenger RNA of the target gene (Supplementary Table 9). Female flies carrying the elav-Gal4 pan-neuronal driver or the repo-Gal4 pan-glial driver were crossed either with males carrying the specified UAS-RNAi or with CS males. Fly progeny were reared at 25 °C throughout their development. Then, 0–1-day-old flies were transferred to fresh food for 1 d before RNA extraction. RNA extraction and complementary DNA synthesis were performed as described elsewhere68,69 using the same reagents: the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (QIAGEN), RNA MinElute Cleanup kit (QIAGEN), oligo(dT)20 primers and the SuperScript III First-Strand kit (Life Technologies). The level of complementary DNA for each gene of interest was compared against the level of the α-Tub84B (Tub, CG1913) reference cDNA. Amplification was performed using a LightCycler 480 (Roche) and the SYBR Green I Master mix (Roche). Reactions were carried out in triplicate. The specificity and size of amplification products were assessed by melting curve analyses. Expression relative to the reference was expressed as a ratio (2 − ΔCp, where Cp is the crossing point). The primers used in this study and results of RT–qPCR data are presented in Supplementary Table 9. For KDs that did not yield memory impairments (negative results), both RNAis were checked by qPCR. For KDs that were induced with two distinct RNAis, at least one of the two RNAi lines was validated by qPCR. Exceptions were for those RNAi constructs that were already validated by RT–qPCR in previous studies, in which case the corresponding reference is indicated (Supplementary Table 10).

Generation of transgenic flies

For the generation of the LexAop-roGFP2-Tsa2ΔCR Drosophila line, the p415 TEF roGFP2-Tsa2ΔCR plasmid (Addgene, #83238)16 was digested by NotI and XbaI. The resulting 1,416-bp fragment was purified by electrophoresis and cloned into a pJFRC19 plasmid (13XLexAop2-IVS-myr::GFP, Addgene, #26224)84. The resulting construct was verified by sequencing (the molecular cloning was outsourced to RD-Biotech, France). Transgenic fly strains were obtained by site-specific embryonic injection of the resulting vector in the attP18 landing site (X chromosome), which was outsourced to Rainbow Transgenic Flies.

The Appl-HA line was generated using the CRISPR approach (outsourced to inDroso). The 3×HA sequence (GCCGCCGTGTACCCCTACGACGTGCCCGACTACGCCGGCTACCCCTACGACGTGCCCGACTACGCCG GCTCCTACCCCTACGACGTGCCCGACTACGCCCCCGCCGCC) preceded by a linker (sequence: GGCGTGGGC) was inserted between the 11th exon and the 3′ UTR of the Appl gene using a guide RNA targeting the sequence AAGTGAAA | GAGTAAGCGAGA. The genomic edition was strictly restricted to the 3×HA tag and linker, preventing any alterations due to the presence of a selection marker (scarless).

Generation of Appl copper-binding mutant by CRISPR

The ApplH(535)R,H(539)R lines was generated using the CRISPR approach, which was outsourced to Rainbow Transgenic Flies. To generate ApplH(535)R,H(539)R, two guide RNAs targeting CCCACGCCTTGGCCCACTAC|CGG and GCGCGCCCTGCACAAGGACC|GGG were employed. The original wild-type genomic sequence GCCCTGCACAAGGACCGGGCCCACGCCTTGGCCCACTACCGGCACCTATTGAACTCTGG, which corresponds to the amino-acids sequence ALHKDRAH(535)ALAH(539)YRHLLNS, was altered to GCCCTGCACAAGGACCGGGCCCGCGCCTTGGCCCGCTACCGGCACCTATTGAACTCTGG, which corresponds to the amino-acids sequence ALHKDRAR(535)ALAR(539)YRHLLNS. The CRISPR strategy was designed to introduce only the specified H/R modifications, and in particular, no marker was associated with the CRISPR-induced mutation. The presence of mutations in Appl was confirmed by Rainbow Transgenic Flies through genomic sequencing.

Appl mutations were generated on a X chromosome carrying y w mutations in an uncontrolled genetic background. To introduce the Canton-Special background appropriate for behavioural experiments, we crossed and y ApplH(535)R,H(539)R w females to wild-type Canton-Special males. At the next F1 generation y ApplH(535)R,H(539)R w/+ females were crossed to Canton-Special males. Given the close proximity of the y gene to Appl and the very low rate of recombination between these two loci (less than 0.03%, as estimated from Flybase data85), the presence of y mutation was employed to recover y Appl mutations in a Canton-Special background. In the F2 generation, recombination between the y Appl and w loci was screened for, and y ApplH(535)R,H(539)R w+/Y males in a Canton-Special background were recovered. Homozygous y ApplH(535)R,H(539)R lines was generated. Concurrently, the parental y w line, which was utilized to induce the CRISPR mutations, was outcrossed with the identical protocol to generate a control y line in a Canton-Special background.

In light of the evidence indicating that y mutations impact LTM (based on our own unpublished observations), to conduct behavioural experiments we crossed y ApplH(535)R,H(539R) females to males carrying the y+ duplication PBac{y[+]-attP-3B}VK00033 (ref. 86) in a Canton-Special background, designated Dp(y+). The offspring were evaluated in behavioural assays to determine the phenotypes of hemizygous y ApplH(535)R,H(539)R/Y; Dp(y+)/+ males compared with y/Y; Dp(y+)/+ males.

Sod3 transcript levels

Relative expression of Sod3 in astrocytes and α/β neurons was obtained from published single-cell transcriptomic data33, according to clustering performed in the original study where astrocytes are found in cluster 10 and α/β in cluster 22.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. For behaviour experiments, two groups of about 30 flies were reciprocally conditioned, using respectively octanol or methylcyclohexanol as the CS+. The memory score was calculated from the performance of two groups as described above, which represents a single experimental replicate. For imaging experiments, one replicate corresponds to one fly brain. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications17,19,37. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. Comparisons of the data series between two conditions were achieved by a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Comparisons between more than two distinct groups were made using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, followed by Tukey pairwise comparisons between the experimental groups and their controls. ANOVA results are presented as the value of the Fisher distribution Fx,y obtained from the data, where x is the number of degrees of freedom between groups and y is the total number of degrees of freedom for the distribution. For copper-rescue experiments (Fig. 6a,b), two-way ANOVA tests were performed, followed by Šidák’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical tests were performed using the GraphPad Prism 8 software. In the figures, asterisks denote the significance level of the t-test, or of the least significant pairwise comparison following ANOVA, with *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant, P > 0.05. Figures were designed using Adobe Illustrator.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses