Avocado consumption during pregnancy linked to lower child food allergy risk: prospective KuBiCo study

Introduction

Maternal exposures, such as nutrition and lifestyle during pregnancy, play a critical role in an offspring’s health outcomes. This includes immunoglobulin E-mediated allergic diseases (or atopic diseases), which encompasses conditions like allergic rhinitis, eczema (or atopic dermatitis), asthma, and wheezing.1,2 Research has noted that different diets or foods during pregnancy may have varying impacts on offspring’s allergic health outcomes. A maternal confectionary diet made up largely of baked and sugary foods may lead to an increased food allergy development in the infant.3 Consuming nutrient poor, proinflammatory diet during pregnancy was also linked to an increased risk of asthma development in their children.4 On the other hand, Venter et al. found that 4-year-old children had fewer allergic outcomes, including allergic rhinitis, eczema, asthma, and wheezing, when their mothers adhered to a higher maternal diet index characterized by higher intakes of yogurt and vegetables during pregnancy.5 Similarly, Chatzi et al. found that a high Mediterranean Diet Score during pregnancy was protective against the development of allergic wheezing and persistent wheezing in offspring at 6.5 years old.6 Although the exact mechanism is still being examined, the literature suggests that antioxidant compounds from foods, such as fruits and vegetables, provide immunomodulating benefits during this critical time for immune development.7

Maternal consumption of individual foods has also been associated with allergic outcomes in offspring. For instance, higher consumption of processed meat or meat products during pregnancy was linked to a higher risk of wheezing within the first year of an infant’s life.6 Alternatively, Willers et al. found maternal apple intake during pregnancy was associated with lower wheezing and asthma among 5-year-old offspring. However, these authors found no significant associations between maternal total fruit intake during pregnancy and allergic respiratory outcomes in offspring.8 This may be due to the unique composition that each fruit has to offer. These findings are helpful when practitioners are trying to communicate practical applications to pregnant women, such as women are inquiring about which foods can help reduce their children’s risk of developing allergic diseases.

Avocados contain numerous vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals, which are known to support immune and metabolic health.9,10,11 However, no study has examined the effects of avocado intake during pregnancy and allergic outcomes among children. Thus, this study aims to investigate how maternal avocado consumption during pregnancy relates to allergic health outcomes in offspring using the Kuopio Birth Cohort (KuBiCo) Study.

Methods

Study population

This prospective cohort study used data from KuBiCo (https://uefconnect.uef.fi/en/group/kuopio-birth-cohort-kubico/), initiated in 2012, with the objective of incorporating approximately 10,000 mother-child pairs. KuBiCo aims to enhance our understanding of the impact of genetic, lifestyle factors, and environmental conditions during pregnancy on maternal and offspring health outcomes.12 KuBiCo extended invitations to pregnant women anticipated to deliver at Kuopio University Hospital (KUH), Finland to join the study, and over 90% of participants were recruited during their routine first-trimester appointments.12 The collection of nutritional data began in March 2013. This study includes pregnant women who filled out nutrition questionnaires between March 2013 and November 2022.

The overall participation in KuBiCo during 2013–2022 (7944 women) has been 37.7% of all parturients giving birth in KUH. These participants reflected the overall population of women who gave birth, considering factors such as maternal age, gestational length, infant sex, and birth weight.12 Data collection included questionnaires, biological samples, and health examinations conducted at various points during pregnancy and at delivery. Following childbirth, KuBiCo maintains annual follow-ups involving questionnaires and health examinations for both the mother and child.12 The KuBiCo database is linked to the hospital birth register and later also national health registries for epidemiological follow-ups.12 Additional details of the KuBiCo Study have been published elsewhere.12

Dietary assessment

Avocado consumption data were collected through an adapted online food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) administered during the first and third trimesters. The KuBiCo FFQ was adapted to include more current food items, comprising a total of 163 items, each with a predefined portion size (in grams). Respondents were asked how often (with nine frequency options) in the past three months they had consumed a food item (e.g., avocado). Portion size and frequency were used to compute an estimated daily intake for each listed item. Lastly, the 2018 National Food Composition (Fineli) database was utilized to determine average daily intakes of energy, food, and nutrients.13 This is a modified version of the FFQ used in the Kuopio Breast Cancer Study; its validity and reliability have been detailed by Männistö et al.14

KuBiCo participants were categorized as avocado consumers or non-consumers. Avocado consumers were defined as participants who reported consuming any avocado (>0 grams) during the first or third trimester, and avocado non-consumers were defined as participants who didn’t report consuming any avocado (0 grams) at both trimesters.

Offspring allergic outcomes

Offspring allergic outcomes were captured in the 12-month follow-up questionnaire. KuBiCo participants were asked (yes/no): “Has your child experienced the following condition during his/her first year of life?” for rhinitis (other than during a cold), paroxysmal wheezing (i.e., acute episodes of wheezing). Self-reported physician-diagnosed conditions were also asked (yes/no): “Has a doctor diagnosed any of the following conditions in your child during his/her first year of life?” for eczema and food allergy.

The four allergic outcomes (rhinitis, paroxysmal wheezing, eczema, and food allergy) were categorized as binary variables (yes or no).

Covariates

The following covariates were considered: maternal age at delivery (continuous), marital status (married, cohabitation, other relationship, divorced or widow, or single), educational level (16 years or less or more than 16 years), parity (nulli- or primiparous or multiparous), body mass index (BMI) at the first trimester (continuous), gestational age at delivery (continuous), caesarean section (yes or no), neonatal intensive care unit (yes or no), breastfeeding – number of months (continuous), alcohol consumption – percentage of total energy/day at trimesters 1 and 3 (continuous), Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at postpartum (continuous), diet quality at trimesters 1 and 3 (continuous), and smoking (not smoking, stopping smoking at 1st trimester, smoking, not known, smoking before pregnancy, stopped smoking after 1st trimester, or passive smoking).

KuBiCo participants completed the EPDS through an online questionnaire at eight weeks postpartum. The EPDS, utilized for screening postpartum depression, is a 10-item questionnaire employing a 4-level Likert scale with scores ranging from 0 to 30.15

Diet quality was estimating using the Alternative Healthy Eating Index for Pregnancy (AHEI-P)16 based on the FFQ data in trimesters 1 and 3. The original AHEI is a valid measure of diet quality that focuses on food items associated with decreased chronic disease risk. To make AHEI more suitable for pregnant women, Rifas-Shiman et al. included folate, calcium, and iron components and excluded the alcohol component, and because some participants may avoid nuts due to allergic sensitization, the nuts and soy protein-component were excluded and tofu and soybeans were included in the vegetable component.17 The AHEI-P contains nine dietary components: vegetables, fruit, the ratio of white to red meat, fiber, trans fat, the ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids, folate, calcium, and iron. Dietary recommendations for pregnant women determine the minimum and maximum points of each component, with a maximum score of 10 points for each component. The scores for the individual dietary components were summed to get the total AHEI-P score for each participant. The total AHEI-P score is on a 90-point scale, and a higher total AHEI-P score indicates better dietary quality.

Statistical analyses

We performed descriptive statistics to compare characteristics between mothers who consumed avocados during pregnancy and those who did not. Maternal characteristics between avocado consumers and non-consumers were compared using chi-square tests and independent sample t-tests. We used logistic regression to examine the association between the two avocado consumer groups during pregnancy and the offspring’s allergic outcome. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for maternal age at delivery, marital status, education, nulliparity, BMI in the first trimester, gestational age at delivery, caesarean section, neonatal intensive care unit admission, breastfeeding, alcohol consumption, EPDS scores, diet quality (AHEI-P), and smoking. Missing values were imputed with the mean adjusted method. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 29, Armonk, NY, and the level of significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Protocol registration and checklist

We developed and registered our study protocol at: https://osf.io/7mrgx. Furthermore, this study also adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist to ensure reporting quality.

Results

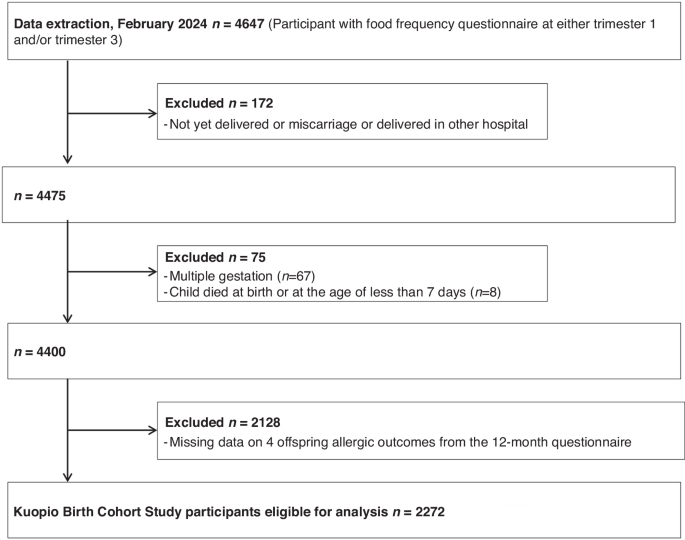

Of the 4647 participants, 2272 met the criteria and were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). Table 1 describes the maternal characteristics from the KuBiCo cohort. On average, the maternal age at delivery was 31.3 years, with more than half of the participants being married. 56.9% of the mothers had completed more than 16 years of education, and over 80% were non-smokers. Most were nulliparous or primiparous, and the average BMI in the first trimester was approximately 25.1 kg/m2. The mean (standard deviation) scores for EPDS and diet quality were 4.5 (4.0) and 58.8 (10.2) in the whole study population, respectively.

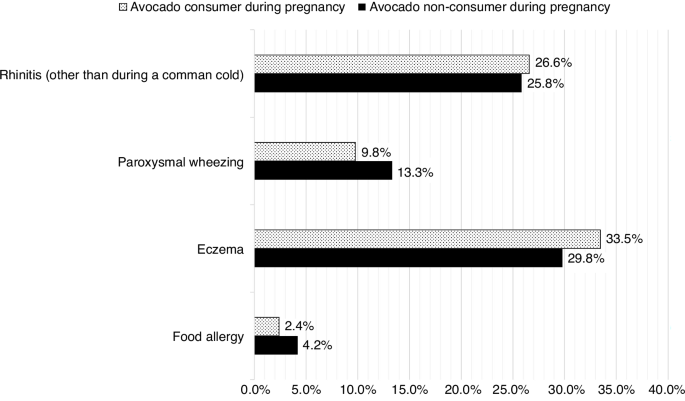

The four allergic outcomes include rhinitis, paroxysmal wheezing, eczema, and food allergy.

Mothers who included avocados in their pregnancy diet, in comparison to those who did not, tended to be older at delivery and less likely to undergo a caesarean delivery. They were also more likely to be non-smokers and have nulli- or primiparous pregnancy. Furthermore, avocado consumers exhibited higher scores for dietary quality, breastfed for a longer duration, and had lower BMI levels.

Compared to avocado non-consumers (during pregnancy), avocado consumers (during pregnancy) had 43.6% lower odds of having food allergy among their infants at the 12-month follow-up questionnaire while adjusted for relevant covariates, which included maternal age at delivery, marital status, education, nulliparity, BMI in the first trimester, gestational age at delivery, caesarean section, neonatal intensive care unit admission, breastfeeding, alcohol consumption, postpartum depression, diet quality, and smoking (Table 2). Food allergy was significantly higher (p = 0.019 in the fully adjusted model) in the offspring of pregnant non-consumers (4.2%) compared to the offspring of pregnant avocado consumers (2.4%) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Similarly, compared to the offspring of gestational avocado consumers (9.8%), offspring of gestational non-consumers (13.3%) had significantly higher paroxysmal wheezing (p = 0.009 in unadjusted model). However, this association attenuated in the fully adjusted model (p = 0.085). No significant associations were noted in the other two allergic health outcomes (rhinitis and eczema).

The bar fill patterns distinguish between avocado consumers and non-consumers during pregnancy. A dotted pattern represents consumers, while a solid fill indicates non-consumers.

Discussion

This analysis used a prospective cohort study to investigate the link between maternal avocado consumption during pregnancy and the offspring’s allergic health outcomes. The findings indicate that 12-month-old infants have lower odds of developing food allergies when their mothers consumed avocados during pregnancy. Importantly, this association remained significant even after adjusting for relevant confounding variables including maternal age at delivery, marital status, education, nulliparity, BMI in the first trimester, gestational age at delivery, caesarean section, neonatal intensive care unit admission, breastfeeding, alcohol consumption, postpartum depression, diet quality, and smoking, which have been shown to have an impact on the development of food allergies. Similar findings were also noted with paroxysmal wheezing, but the association attenuated in the fully adjusted model. No significant associations were observed between maternal avocado consumption and the other available allergic health outcomes (rhinitis and eczema) in their offspring.

While our findings are the first to report on maternal avocado consumption and offspring allergy, decades of previous research have explored the relationship between maternal diet, in terms of specific dietary patterns, food groups, and food items, and offspring allergic outcomes.1,18,19,20,21,22,23 Our findings align with the previous research on vegetarian and Mediterranean dietary patterns. First, one avocado provides 13.3 grams of monounsaturated fatty acids and 9.5 grams of dietary fiber; and its nutrient profile aligns well with the Mediterranean and vegetarian diets.24 Moreover, studies suggest that maternal Mediterranean dietary patterns are associated with fewer allergic outcomes in offspring. For example, Chatzi et al. studied 460 mother and child pairs in Spain and found that mothers with higher Mediterranean Diet Score during pregnancy had lower odds of their offspring developing wheezing and atopy after 6.5 years of follow-up while controlling for relevant covariates.6 The Japan Environment and Children’s Study also observed similar results, which found that those with higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet during pregnancy had a lower risk of their children developing asthma or one or more allergies at four years old.25 Furthermore, the Taiwan Birth Study observed a lower incidence of child eczema before 18 months among mothers who followed a vegetarian diet during pregnancy.26 However, two studies did not find any association between maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy and allergic health outcomes among their offspring.22,23

Consuming certain food groups has also been associated with a lower risk of allergic health outcomes among offspring. In the EDEN birth cohort with 1140 mother and child pairs, higher consumption of raw vegetables (which included avocado) during pregnancy was associated with a lower risk of allergic rhinitis among offspring at three years old.27 Similar results with fruits and vegetables were also noted in the Finnish Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention Nutrition Study28 and a Japanese cohort.29

However, fewer studies have looked at individual food items and their impact on allergies. Willers et al. found that maternal apple intake during pregnancy was associated with lower wheezing and asthma among offspring at five years old.8 Another study found that children born to mothers who consumed legumes once a month or less were at a heightened risk of belonging to the ‘multi-allergic’ cluster, suggesting a potential role for legume consumption in preventing allergic diseases.30 A third study observed an inverse association between maternal intake of peanuts and tree nuts and the prevalence of asthma in 18-month-old toddlers.31 The dietary pattern and food group research is likely confounded by each food’s unique nutrient and bioactive composition. Overall, very little data exists to support specific food recommendations for maternal diets to impact allergies.

The potential benefit of avocados during pregnancy might be explained by various mechanisms at the nutrient level (e.g., antioxidants, fiber, and monounsaturated fat). First, researchers hypothesized that prenatal antioxidant exposure may program the child’s susceptibility to allergic health outcomes in utero through changing T-cell responses.32,33 Although results are mixed, some existing observational studies have shown an inverse relationship between offspring allergic health outcomes and antioxidant consumption during pregnancy, including vitamin E2,34,35,36 and zinc.2,35 One avocado provides 2.6 mg of vitamin E (18% of the Daily Value) and 0.93 mg of zinc.37 Secondly, one avocado also provides 9.25 grams of fiber,37 which has been shown to be a significant factor in shaping the gastrointestinal tract microbial community, microbial fermentation, and subsequent host immune maturation.19 Preclinical studies have shown that maternal gut microbial-produced short-chain fatty acids from fiber consumption during pregnancy modulate key immune pathways via epigenetic effects in the fetus, ultimately improving or preventing the offspring’s allergic responses.38,39 Fiber may even have a protective effect later in life. Among adults, higher fiber consumption appeared protective against wheezing and other respiratory symptoms.40,41 However, there are limited studies on this topic among mother-children pairs.41,42 Lastly, avocados are abundant in monounsaturated fats (13.3 grams in one fruit). Studies have shown that monounsaturated fats can modulate immunological response and were inversely related to asthma in both adolescents and adults.43,44 Similar to dietary fiber, there are limited studies on this topic among mother-child pairs.

Our results suggest that 12-month-old infants were less likely to develop food allergies when their mothers consumed avocado during pregnancy. However, no association between maternal avocado intake and the other three allergic health outcomes was found. One plausible explanation for this divergence could be the varying timelines for developing or manifesting these allergic diseases.45 For example, food allergies typically emerge between the ages of 6 and 12 months, coinciding with the introduction of solid foods.45 In contrast, only 50% of children with eczema exhibit symptoms in their first year of life, and 95% experience onset within the initial five years of life.45 Similarly, rhinitis also develops later in childhood.45 Given that our assessment was based on outcomes at 12 months of age, it is possible that some of these allergic diseases may not have manifested yet. Further research is warranted to reproduce this study with outcomes assessed at different age intervals.

This study included several strengths. First, this prospective cohort study allows a better understanding of the temporal relationship between exposure and health outcomes.46 Second, avocado intake was assessed with an FFQ, more representative of the usual intake of sporadically consumed foods such as avocado.47 Third, the final model accounted for several covariates to better comprehend the association between avocado consumption during pregnancy and allergic health outcomes in their children. However, several limitations should be highlighted. First, these analyses relied on self-reported dietary intake and health outcomes. This may introduce recall and measurement biases, leading to an underestimation of the true effect of the other potential confounding factors. Second, although this paper focused on avocado consumption, a single food item, it may be an indicator of broader vegetarian dietary patterns that are not fully characterized. However, we attempted to account for this by adjusting for AHEI-P in our models. Third, only pregnant women likely to deliver at Kuopio University Hospital were recruited and close to 50% of the original participants were excluded. This may limit the generalizability of the results. However, the characteristics of the participants were representative of the overall population of women who gave birth in Finland.12 Lastly, although we adjusted for relevant covariates, an observational study design may be susceptible to residual confounding.

Conclusions

This prospective cohort study demonstrated that 12-month-old infants have lower odds of developing food allergies if their mothers consumed avocado during pregnancy. The association persisted even when accounting for potential covariates. Future studies are warranted to explore this association in other populations.

Responses