Awareness of human microbiome may promote healthier lifestyle and more positive environmental attitudes

Introduction

The human microbiome consists of trillions of symbiotic microbial cells occupying the human body, notably the gut. The new definition of the term microbiome proposed by a panel of international experts, recognizes these microbial communities as dynamic micro-ecosystems integrated in the host’s macro-ecosystems, and crucial for their functioning and health1. Recent scientific findings on human microbiome (HM) promise a variety of personalized therapeutic and self-help applications2,3,4. But there are still multiple technical, methodological, and conceptual challenges5,6: the complexity of the subject makes it difficult even to tell what defines a healthy microbiome7.

While research on the mechanisms underlying the ecology and host-interactions of these highly complex ecosystems continues to advance, consumer markets for probiotics are steadily growing8,9. Companies offer tests and products allegedly allowing consumers to improve their microbiome health: practices referred to as “commercialized intervention”10. Some commercial products may lack effectiveness and even pose risks for the consumer’s microbiome and external environment11. This raises ethical and regulatory challenges, but also calls for a better understanding of how people learn and make decisions regarding their microbiome.

Despite the scientific development in the HM field and the commercial hype surrounding it, informed public knowledge regarding the microbiome remains limited12,13,14,15,16. Several studies assessed public knowledge of HM and practices such as the use of probiotics and antibiotics12,13,14,15,17,18. The International Microbiota Observatory by the Biocodex Microbiota Institute12 pointed at differences between several Western and non-Western countries in knowledge and practices related to microbiota health. More large-scale and cross-national studies are needed to investigate various aspects of the public attitudes towards HM.

In this study we aimed to explore several questions that gained little research attention so far. These include public preferences that may underlie behavioral intentions and choices, possible cross-cultural differences, and the relation of HM concepts to personal identity and environmental attitudes. In an online survey (N = 2860), we explored how people learn about the HM, the willingness to self-monitor and maintain the health of one’s microbiome and the preferred ways to do this. Such data could be relevant for policy makers and health professionals and could contribute to health communication strategies. Conducting the survey in France, Germany, South Korea, and Taiwan allowed us to compare attitudes to the HM and microbial world in European and Asian countries.

Another dimension of the study involved perceptions of the HM as part of a larger environmental worldview. Systemic approaches to life and environment become ever more prominent in science. Microbiome emerges as a vital element within the One Health concept, which emphasizes the connection of human, animal, and environmental health19,20. The HM is often viewed as a hidden or virtual organ21,22, and the conceptions emerged of our bodies as symbiotic “holobionts”23,24. The images of our bodies—and our planet—as superorganisms shared by interdependent and collaborative communities of living species are being popularized and increasingly gain public attention25,26,27,28.

Recognizing an ecosystem dimension within oneself may contribute to a broader environmental perspective. The HM represents a natural embeddedness and collaboration of humans with internalized “otherness”. Does awareness of such collaboration impact how we feel about it, how we view ourselves and the invisible kingdom of microorganisms? To explore this, we asked the survey participants to report their associations with microbes and to rate how positive or negative these were (we broadly refer to this as “perceptions”). Then, using a quasi-experimental set-up (a moment of reflection on HM) we tested whether active awareness of HM could facilitate a shift in how people view microorganisms. Could realizing the role of the HM as our “internal environment” potentially help us assume a wider, less anthropocentric, environmental perspective and acknowledge microorganisms as our ecological partners at multiple scales?

To summarize, the research objectives of the study included: assessing how people obtain information on the HM; exploring public preferences related to monitoring, sustaining and improving of one’s microbiome health; testing whether awareness of one’s microbiome may influence attitudes to microorganisms in a broader environmental sense; exploring possible intercultural differences in perceptions and attitudes regarding the HM.

Our study shows that the public recognize the essential role of the HM in health and are willing to take care of it, which may have implications for public health policy. Our findings also suggest that stronger awareness of the HM may promote lifestyle change and a more encompassing environmental outlook.

Methods

Sampling and data collection

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey with 2860 respondents using nationally representative samples from France (n = 720), Germany (n = 705), South Korea (n = 714) and Taiwan (n = 719). The recruitment and data collection were performed by the ISO 20252-certified market and research panel agency Bilendi. The respondents were recruited from Bilendi panels in France and Germany, and from their partners’ panels in South Korea and Taiwan. All panelists were reimbursed for their time with “points” exchangeable for gifts from the panel shop. The respondents were quota-sampled to represent adult national population of each country on gender, age, and education level (Supplementary Table 1). Individuals younger than 18 years old were excluded from participation. Ethics approval was granted by the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Erasmus School of Philosophy, Erasmus University Rotterdam (ETH2324-0309).

The data were collected between January 15–29, 2024. Bilendi organized the removal of invalid responses from the data, such as incomplete entries and obvious speeders. Two entries with gibberish in all text fields were removed from the dataset by the authors prior to the analyses, resulting in 2858 valid responses.

Research design

The survey questionnaire is availalbe in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Method). After receiving the information on the survey and providing informed consent, the participants answered questions on their gender, age, education, whether their work was related to healthcare or life sciences, and on one’s belief. The latter question was borrowed from Eurobarometer29 and distinguished between belief in God, some sort of spirit or life force, or neither. Next, participants were asked to share their perceptions about microbes (images and words that come to one’s mind) and rate them on a 7-point Likert scale (1 for extremely negative, 4 for neutral and 7 for extremely positive). All measuring scales in the study were 7-point Likert scales.

Since many people have little affinity with the topic, we proceeded with a short information display on HM and its importance for physical health and mental wellbeing. Then, the participants were assessed on (1) their familiarity with HM and the main sources of information on it, (2) the estimated role of HM for one’s physical health and mental wellbeing, (3) their attitudes towards HM monitoring and managing. The latter included willingness to monitor the health of one’s microbiome and how much one relies on one’s feelings and bodily experience vs. the information/techniques obtained from healthcare professionals to estimate its health. We also assessed how much people prefer to improve/sustain the health of their microbiome by lifestyle adjustment (such as diet and exercise), and how much they are willing to buy special products to improve their microbiome health.

The participants were then invited to briefly contemplate on the HM (“Please pause for a moment and think about this: There are trillions of living microorganisms inside your body. Actually, more than the number of cells your body is made of. These microorganisms form communities and contribute to your health and wellbeing”). Importantly, this moment of reflection was not meant as pure information but as a way of integrating basic knowledge with a more imaginative and emotionally engaging element. The participants were then asked to report and rate their perceptions again. The one-group pretest-posttest design integrated in this part of the survey is a quasi-experimental approach often used in educational and social intervention research30,31; we will address its limitations separately.

Participants were further asked if awareness of HM affected their image of who they are (for brevity, we will refer to this here as self-image), and whether it changed the way they look at microbes and microbial world (made them think more negatively or positively about them, with an option to share more thoughts). Finally, participants were asked to rate how willing they would be to take part in citizen-science projects regarding the HM. After a debriefing section, one could comment on the survey via an open textbox. The survey took ca. 6 min to complete.

Statistics and reproducibility

The data was organized using Microsoft Excel, and statistical analyses were carried out using JASP (version 0.18.3). For the exploratory part of the study, descriptive statistical analysis (means and frequencies) and network analysis were employed. For the quasi-experimental intervention, paired samples t-tests were used to compare how respondents rated their images of microbes before and after the reflection exercise. A p-value of .05 was adopted as a threshold for statistical significance. Cohen’s d was interpreted as follows: 0.2 for standard deviation between the means as a small effect size, 0.5 as moderate and 0.8 as large32. All variables under study were normally distributed (all skewness values between −0.43 and −0.03).

Network analysis

Network modelling offers a complexity-accommodating data-based perspective on phenomena in various disciplines33, including the analysis of attitudes34 (see Dalege et al.35 for Causal Attitude Network model). Such frameworks can help gain insights about the structure of causal or correlational data36. In an abstract network representation, nodes (points/circles) represent any entities or variables, whereas edges (links) denote any form of connection/relation. The magnitude of edges reflects the strength of connections estimated from the data (weighted network). In our analysis, the edges represent partial correlations between the variables (using EBICglasso estimation method37). The variables/nodes include self-reported knowledge (familiarity), recognizing the role of the HM for physical health and mental wellbeing, reliance on microbiome information from doctors vs. bodily experience, willingness to monitor one’s microbiome’s health, adjust one’s lifestyle, or buy special products.

Centrality measures (betweenness, closeness and strength) further characterize the roles and prominence of the edges. Betweenness reflects the number of times a given node is a shortest path between two other nodes; higher betweenness quantifies how important a node is in connecting other nodes and potentially in controlling communication between them38. Closeness sums the shortest paths between each node to all other nodes; it could be interpreted as independence from control or as a measure of efficiency39. The strength measure is the sum of the edge values of a given node representing its influence on the network34.

To estimate the robustness and stability of the network, we followed Epskamp et al.40. First, we performed non-parametric bootstrapping (data resampling based on replacement, advisable for ordinal data; we used 1000 replications) to evaluate the network connections by computing bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Next, we evaluated the stability of the centrality indices using case-dropping bootstrapping (1000 bootstraps). This method shows, which proportion of the data could be dropped while maintaining the 95% probability of a high correlation between the initial centrality indices and those of networks based on smaller subsets. The correlation stability coefficient (CS-C) should be no less than 0.25 and preferably above 0.5, with 0.7 indicating high stability40.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Network analysis

We performed the network analysis including centrality indices measures for the entire dataset (Supplementary Figs. 1–2, see Supplementary Information) and per country (Supplementary Fig. 3 and 1). Non-parametric bootstrapped CIs remained consistent with the original samples both for the overall network and per country (Supplementary Fig. 3 and 6). The case-dropping subset bootstrapping showed stable centrality indices after dropping up to 75% of the sample across all networks. The CS-Cs were above 0.8 for the aggregated network (Supplementary Fig. 4), above 0.7 for France and Germany, and even the lowest CS-Cs (closeness and betweenness for South Korea and Taiwan) were above 0.5 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

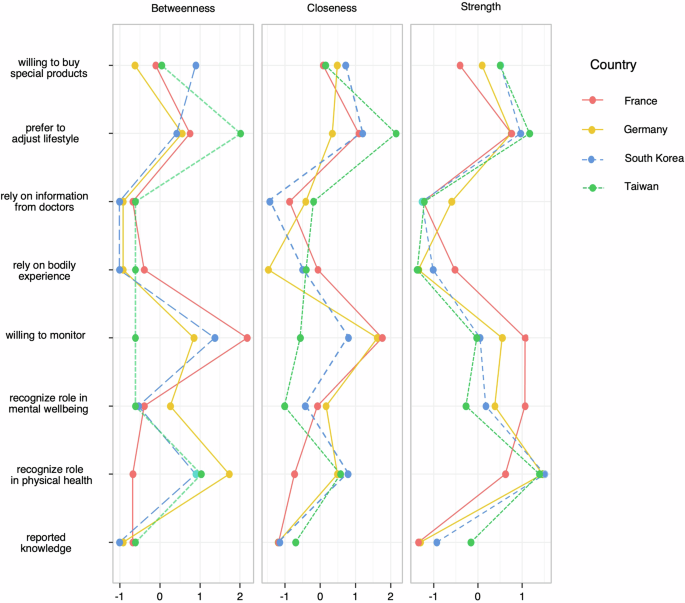

The plots of the estimated network for Asian countries demonstrate more connections between the edges, whereas the plots for France and especially Germany exhibit lower global network connectivity (Supplementary Fig. 3). Recognizing the role of HM in one’s physical health is quantified as the first node in strength and the second in betweenness. Preference to adjust lifestyle to sustain/improve the health of one’s microbiome is the second strongest node and the first for both closeness and betweenness measures. The second prominent node for closeness is willingness to monitor one’s microbiome’s health. Plots per country (Fig. 1) show some variations. For example, in France, the strongest nodes were the willingness to monitor one’s microbiome and the recognition of the HM’s role in mental wellbeing.

The plot presents three indices (betweenness, closeness and strength, shown as standardized z-scores) for the centrality measures of the estimated network. Total sample: N = 2858; France: n = 720; Germany: n = 705; South Korea: n = 714; Taiwan: n = 719.

How people learn about HM

The mean self-reported familiarity with HM (we interchangeably refer to it as “knowledge” here) was 3.31 (SD = 1.58) on a scale of 7 (1 indicating “no knowledge at all”, 4 “not sure” and 7 “a lot of knowledge”). The average score was lowest for Germany (M = 2.86; SD = 1.53), followed by France (M = 3.08; SD = 1.67). Taiwan and South Korea had somewhat higher scores (M = 3.63; SD = 1.59 and M = 3.65; SD = 1.38, respectively). In France and Germany, about a quarter of respondents reported to have no knowledge regarding the HM at all, which was ca. 9% and 12% in South Korea and Taiwan, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Respondents with higher education reported somewhat more knowledge of HM than those with lower education (M = 3.63; SD = 1.52 vs. M = 3.11; SD = 1.59). The mean knowledge reported by participants working in healthcare or life sciences (11% of all respondents) was 4.28 (SD = 1.52) vs. 3.19 by the others (SD = 1.55). Individuals who were 55–64 and especially 65+ years old reported the lowest knowledge (M = 3.25; SD = 1.55 and M = 2.94; SD = 1.50, respectively). Self-reported knowledge was also low among participants who reported to believe neither in God, nor in any spirit or life force (M = 3.05; SD = 1.53).

Table 1 presents the main sources of information on HM reported by the participants. In all four countries, television belonged to the top three information sources. Other sources included healthcare professionals (except for South Korea), internet websites/blogs (except for Taiwan), press for South Korea and social media for Taiwan. The least mentioned sources included companies offering special products (especially, for France and Germany), social media in the European countries, and family/friends in Asian countries.

Estimated role of HM in health and wellbeing

Respondents were asked how much they believed their microbiome to affect their physical health and mental wellbeing. On a 7-point scale (1 indicating “not at all”, 4 “not sure” and 7 “very much so”) the mean was 4.97 for physical health (SD = 1.3) and 4.59 for mental wellbeing (SD = 1.33). Supplementary Figs. 6–9 show the score distribution per country and between countries. Most respondents acknowledged the importance of HM for their physical health (from 54% in France to 65% in the Asian countries), whereas about 30–33% of respondents in each country were unsure. Less people recognized the role HM may play in their mental wellbeing (from 45% in France to 51% in South Korea). The number of participants unsure about it varied between 31% in France and 41–42% in other countries.

Among the age groups, acknowledging the role of HM for one’s health was highest for the 55–64-year-olds (M = 5.09; SD = 1.24 for physical health and M = 4.74; SD = 1.28 for mental wellbeing). Higher educated participants recognized the role of HM more (M = 5.17; SD = 1.19 for physical health and M = 4.73; SD = 1.23 for mental wellbeing). Being a non-believer was associated with somewhat lower scores (M = 4.7; SD = 4.62 and M = 4.29; SD = 4.2, respectively).

Preferences in monitoring and sustaining HM health

We asked the participants to rate their willingness to monitor the health of their microbiome (on a scale of 7, 1 indicating “not at all”, 4 “neutral” and 7 “extremely”). The majority of participants expressed willingness to do this (M = 4.68, SD = 1.45). Respondents in Europe demonstrated a higher readiness than those in Asia (56–57% vs. 49–51%). Supplementary Figs. 10–11 show the score distribution per country and among the countries.

Participants rated how much they agreed (on a scale of 7, 1 indicating “strongly disagree”, 4 “neutral” and 7 “strongly agree”) that to estimate the health of their microbiome they relied on their own feelings and bodily experiences (M = 4.63, SD = 1.29) vs. information and techniques from healthcare professionals (M = 4.72, SD = 1.38). Trust in one’s bodily experience as indicator of healthy microbiome ranged between 44% in South Korea and 61% in France, whereas relying on doctors’ tips ranged between 46% in Germany and 57% in France and Taiwan. Score distributions per country and between countries are presented in Supplementary Figs. 12–15.

To sustain and improve the health of one’s microbiome the respondents showed willingness to adjust their lifestyle such as diet and exercise (M = 5.08, SD = 1.31) as well as to buy special products (M = 4.43, SD = 1.49). In Taiwan and France as many as 70–71% of the respondents would be willing to adjust their lifestyle (M = 5.29, SD = 1.26 and M = 5.22, SD = 1.37, respectively). For Germany and South Korea, it was 58–60%. Interest in special products was somewhat higher in Asia (51–54% vs. 40–42% in Europe). Supplementary Figs. 16–19 show score distributions on these questions.

The participants with higher education expressed the highest willingness to monitor their microbiome health (M = 4.8, SD = 1.32), relied most both on their bodily experience and doctor’s advice (M = 4.71, SD = 1.26 and M = 4.85, SD = 1.32), and showed most readiness to adjust their lifestyle and to buy special products (M = 5.3, SD = 1.2 and M = 4.7, SD = 1.4). The respondents working in healthcare and life sciences reported higher scores than the individuals in other professional fields: their mean score for being ready to keep an eye on one’s microbiome health was 5.13 (SD = 1.36), for relying on one’s bodily experience and doctor’s tips 5.02 and 5.06 (SD = 1.2.8 in both cases), and 5.45 and 4.88, respectively, for lifestyle adjustments and buying special products (SD = 1.23 and SD = 1.5). The scores reported by non-believers were lower in all areas: the mean score for willingness to observe one’s microbiome health was 4.44 (SD = 1.47), for attuning to one’s feelings and to doctor’s advice 4.4 and 4.55 (SD = 1.31 and SD = 1.42), and for intending to change one’s lifestyle or buy special products 4.79 and 4.06, respectively (SD = 1.36 and SD = 1.52).

Environmental perceptions related to HM

A paired samples t-test shows a slight positive shift in perceptions of microorganisms following a moment of reflection on the HM (M = 4.71, SD = 1.24) compared to baseline (M = 4.04, SD = 1.36, T = -22.55, p < 0.001). The effect size was rather small (Cohen’s d of 0.42). A statistically significant effect (p < 0.001) was observed for each of the four countries. France had the largest change in mean score (from M = 3.46, SD = 0.06 to M = 4.65, SD = 0.04) with a moderate effect size of 0.67. In Germany the score increased from M = 4.13 (SD = 1.08) to M = 4.66 (SD = 1.26). In South Korea and Taiwan, the rating increased from M = 4.25 (SD = 1.32) to M = 4.74 (SD = 1.2) and from M = 4.32 (SD = 1.28) to M = 4.79 (SD = 1.31) respectively. The effect sizes for Germany, South Korea and Taiwan were small (0.36, 0.32 and 0.36, respectively). An overview of mean changes across the four countries is presented in Supplementary Fig. 22.

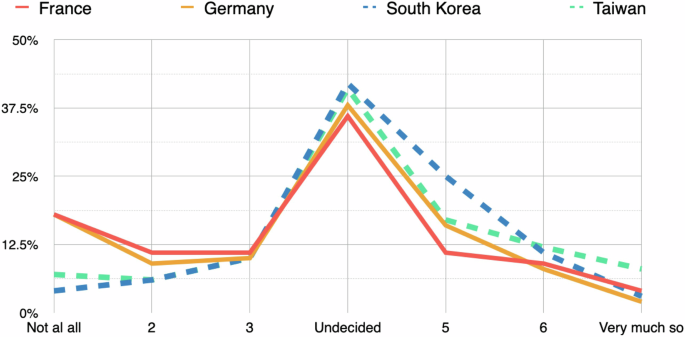

The mean results for change in self-image were slightly below 4 (the indicator of “undecided”) for France and Germany (M = 3.54; SD = 1.68 and M = 3.59; SD = 1.6). South Korea and Taiwan had a mean of 4.2 (SD = 1.26 and SD = 1.5, respectively). The largest proportion of respondents in each country chose “undecided” to the question whether the awareness of microbiome influenced the image of who they are: 36% in France, 38% in Germany, 42% in South Korea and 41% in Taiwan.

In France ca. 40% of respondents chose scores between 1 and 3, indicating that awareness of microbiome did not affect their self-image. The scores from 5 to 7 (7 indicating strong influence) were chosen by 24% of the participants. In Germany these proportions were 36% and 26%, respectively. Asian countries demonstrated a reversed pattern. In South Korea 20% of participants reported no influence of microbiome awareness on their self-image, whereas 38% reported such influence. For Taiwan these proportions were 23% and 36%, respectively. The proportion of participants highly affected by awareness of HM (scores 6 and 7) ranged between 11% (in Germany) and 19% (in Taiwan). An overview of score distributions is provided in Fig. 2.

The respondents were asked whether the awareness about microbiome influenced the image of who they are. Total sample: N = 2858; France: n = 720; Germany: n = 705; South Korea: n = 714; Taiwan: n = 719.

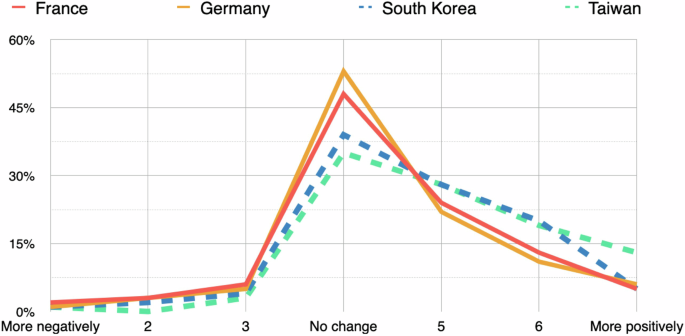

The question on how awareness of HM affected one’s attitude towards microbes and the microbial world resulted in the mean score of 4.48 in France (SD = 1.16), 4.49 in Germany (SD = 1.07), 4.73 in South Korea (SD = 1.12) and 4.99 in Taiwan (SD = 1.19). Many participants reported a positive change. It was largest in Taiwan (61% with scores from 5 to 7 and 32% who scored 6 and 7) and in South Korea (53% and 26%, respectively). These numbers were somewhat lower but still impressive in France (42% and 18%) and in Germany (38% and 17%). The proportion of participants who reported no change was the highest: 48% in France, 53% in Germany, 39% in South Korea and 35% in Taiwan. Some respondents reported a more negative attitude (11% in France, 8% in Germany and South Korea and 4% in Taiwan). An overview of score distributions is provided in Fig. 3.

The respondents were asked how the awareness about microbiome makes them look at microbes and the microbial world. Total sample: N = 2858; France: n = 720; Germany: n = 705; South Korea: n = 714; Taiwan: n = 719.

Demographically, the highest change in one’s self-image was reported by higher educated participants (M = 4.07; SD = 1.5), and by those working in healthcare or life sciences (M = 4.33; SD = 1.67), whereas non-believers reported lower scores (M = 3.55; SD = 1.54). These demographics also reported a more positive view on microorganisms: the mean score for higher educated respondents was 4.85 (SD = 1.11), for healthcare and life science professionals 5.03 (SD = 1.17); it was 4.4 for non-believers 4.4 (SD = 1.13).

Willingness to engage in HM citizen science projects

About half of the survey participants (from 45% in South Korea to 51% in Taiwan) demonstrated some willingness to be involved in research projects where citizens collect and share data on their microbiome to promote public health (overall M = 4.47; SD = 1.66). The mean score was highest among healthcare and life science professionals (M = 5.01; SD = 1.53) and respondents with higher education degree (M = 4.65; SD = 1.59), whereas non-believers showed less interest in doing so (M = 4.18; SD = 1.71).

Discussion

Consistent with the findings from multiple studies12,13,14,15,16, our survey confirms the limited public familiarity with the HM. In contrast to other studies12,13,14,15,17,18, we accessed neither the level/accuracy of knowledge, nor the HM-related practices, but focused on more general aspects. To our knowledge, no public surveys so far have studied these attitudes and preferences regarding the HM. Also, we are unaware of any prior research exploring whether microbiome awareness could contribute to one’s environmental perspective. The strength of the current survey lies in its exploration of these aspects with large representative population samples from different world regions.

The descriptive statistics point at considerable recognition of the role of HM for physical health (54–65% of participants per country), whereas less respondents acknowledged its importance for mental wellbeing (45–51%). Most participants (58–71%) reported a willingness to adjust their lifestyle (such as diet and exercise) to sustain or improve the health of their microbiome: this was the second strongest attitude in the network centrality plot. Interest in buying special products (40–54%) and willingness to monitor one’s microbiome health (49–57%) were prominent as well. The attitudes of trusting one’s bodily experience or relying on doctor’s advice to estimate the health of one’s microbiome, shared by 44–61% and 46–57% of participants, respectively, appeared less pronounced in the network centrality plot, suggesting their less important role in the evaluative process.

Prior research12 revealed strong national differences in HM-related knowledge and practices. We hypothesized that public attitudes could differ among countries as well as regions, e.g., between European and Asian countries. Several such differences were, indeed, revealed in this survey. Firstly, a quarter of participants in France and Germany reported no familiarity with HM at all, compared to 9–12% of respondents in South Korea and Taiwan. The willingness to monitor the health of one’s microbiome was somewhat stronger in Europe (particularly in Germany), whereas the interest in buying special products was higher in Asia.

Connectivity of the network structure plots in our network analysis illustrates the predictive dimension of self-reported behavioral intentions. Connectivity reflects both evaluative reactions and information processing, and higher connectivity was found to be more predictive of behavior41. In our study, the attitude networks were highly connected in the Asian countries (especially, Taiwan) but less in the European countries, where participants were less familiar with HM. This indicates that the attitudes expressed in the survey could be more stable (and more predictive) for Asian respondents.

From a demographic perspective, higher education and working in healthcare or life sciences were consistently associated with higher scores in all areas (the familiairity with HM, recognizing the importance of HM, willingness to observe and boost one’s microbiome health, readiness to engage in citizen science projects and reporting shifts in self-image and environmental attitude following reflection on the HM). Surprisingly, participants who reported believing neither in God, nor in any spirit or life force demonstrated the lowest results in all these categories. Non-believers comprised ca. 31% of all respondents, typically had lower education (68%), often came from Europe (60%) and were at least 55 years old (43%). Even though differences in education contribute to the responses of this specific group, they do not fully explain the effect. This skeptical attitude deserves further research. Finally, respondents of 55+ years old reported less familiarity with HM, but those in the age category of 55–64 years old acknowledged the importance of the HM for physical health and mental wellbeing the most.

Our survey offers a glimpse into public attitudes and preferences, which underlie behavioral intentions and potential choices related to HM. This includes attitudes and preferences shared across cultures and those observed at regional and country levels, taking demographic aspects into account. The survey summarizes the leading sources from which the publics presently learn about the HM, identifies the preferred means of attaining and sustaining a healthy microbiome, assesses potential consumer receptiveness to commercial offers, and shows how awareness of the HM may contribute to popular health concepts. Such data are relevant for global and national healthcare policy and communication related to HM. Importantly, our findings suggest that higher awareness of HM and its essential place in human health could contribute to healthier lifestyle choices.

Could HM also help expand one’s ecosystem awareness? Microbiome research invites us to see ourselves as ecosystems and holobionts, and this comes with ethical implications. HM care or stewardship involves adopting a more interactive and dynamic understanding of microbiome health as the outcome of multifactorial processes, including cultural aspects. Furthermore, microbiome research supports the shift towards a more holistic and interdependent view of life, where microbes are not external threats but partners and part of what we are42.

Following a momentary reflection on the sheer number of microorganisms in the human body and their contribution to our health, our respondents described and rated their perception of microorganisms, and we compared these results with their baseline scores. A paired samples t-test shows a subtle but statistically significant positive shift in how the participants rated their images and thoughts of microbes after reflection. The most spectacular results were observed in France, where initial associations were quite negative, and the mean score increased from 3.46 to 4.65.

Attitude changes occurring after reflection are consistent with dual-process theories that differentiate between a mindful cognitively effortful (central) and a heuristic (peripheral) information processing route. For instance, Kahneman43 distinguishes between an automatic “System 1” associated with cognitive ease and fast heuristic and intuitive judgement, and a slower, more attentive and deliberative “System 2”. In the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion by Petty and Cacioppo44, motivation and ability to process topic-relevant information lead to cognitive structure change and result in a more enduring attitude shift predictive of behavior, whereas more passive peripheral processing is associated with retaining or falling back to one’s initial attitudes.

Acknowledging HM as an essential element of our healthy functioning was not necessarily linked to a shift in self-image. In France, as many as 40% of the participants explicitly stated that awareness of HM did not affect their image of themselves. Nevertheless, from 26% of participants in Germany to 38% in Taiwan reported some impact on their self-image. Furthermore, a substantial part of participants (from 38% in Germany to 61% in Taiwan) reported that awareness of HM positively changed the way they look at microbes and the microbial world. Interestingly, more participants in Asia reported such a change, whereas there was a stronger positive shift in perceptions regarding microbes in Europe. This may reflect a more conscious recognition of one’s attitudes and perceptions on this subject among Asian respondents, who were more familiar with the topic of HM and already had higher baseline scores. Overall, public awareness of HM seems to involve an environmental dimension.

The study has several limitations. It included 4 high-income countries with developed healthcare systems, which could be important for shaping public attitudes to the HM. The data were collected at one point in time, while attitudes and intentions may change over time. Furthermore, cross-sectional survey designs do not account for causal inferences. Importantly, pretest-posttest results may be affected by confounders such as being exposed to the same question twice, willingness to please the researchers or to be consistent with one’s prior scores. Whereas having no control group is a clear limitation of our quasi-experimental design, it had to do with incorporating the pilot exercise element into a broader survey. Namely, the reflection exercise was closely related to the survey subject in general. It would be hard to exclude active awareness of HM for any group of respondents, but also to discern those, who did not take the reflection moment seriously. Needless to say, subsequent research would require a control group to better assess causal relations between the initial and final test measures. Notwithstanding this, the current test yields preliminary insights into the interface of the HM awareness and ecological mindset, a topic not yet explored empirically. Future studies should investigate aspects of public attitudes, behavior and concepts related to HM and conduct true experiments with control groups, using improved interventions, which integrate information with more engaged environmental awareness.

Accepting microorganisms as our internal “partners” (or even part of what we are) calls for a different perspective on the relationship between humans and the huge microbial realm: a relationship, which is not about dominance but about symbiosis, balance and even stewardship. Such outlook could lead to more responsible ecological strategies at individual and collective levels. Overall, our results suggest an increasing public readiness to embrace more complex concepts of health (such as the One Health approach), the human body, and our interaction with microorganisms.

As microbiome research advances, it should inform public HM awareness. Insights concerning the views and values involved in microbiome care by citizens are relevant for healthcare policy and communication and for the microbiome research community. The present study makes clear that the publics are prepared to recognize the essential role of HM in health and willing to take care of it. Our findings suggest that stronger awareness of HM may contribute to healthier lifestyles as well as to novel health concepts. Finally, a better understanding of our interdependent dynamic relationship with microbial consortia could facilitate broader environmental awareness, promoting responsible interaction with microorganisms and respect for complex ecosystems.

Responses