Baseline gut microbiome alpha diversity predicts chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with breast cancer

Introduction

Chemotherapy is the gold-standard treatment for many types of cancer. An estimated 500,000 patients in the United States receive chemotherapy each year1. Chemotherapy-associated gastrointestinal side effects are common, with up to 90% of patients reporting diarrhea2, nausea, and/or vomiting3,4,5. These side effects are poorly managed6,7,8 and cause treatment delays and dose reductions, ultimately contributing to morbidity and mortality9. Despite these debilitating gastrointestinal side effects, chemotherapy is highly effective at increasing survival in cancer patients. Thus, predicting and minimizing dose-limiting side effects is important not only for patient quality of life but also for treatment efficacy.

Recent studies have reported shifts in the gut microbiome community structure over chemotherapy treatment in breast cancer patients10,11,12. Furthermore, some reports have indicated that higher gut microbial diversity at baseline predicts better tumor responses after chemotherapy13,14. Here, we extend this line of questioning by examining the extent to which the composition of the gut microbiome before chemotherapy relates to the dose-reducing gastrointestinal side effects of chemotherapy.

Indeed, known risk factors for chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms are female sex and younger age15,16, which are not modifiable. Thus, potential risk factors that are modifiable and predict gastrointestinal side effects after chemotherapy would be useful in identifying at-risk patients and would allow for potential preventative treatments prior to chemotherapy administration. Chemotherapy-induced gut microbiome disruption is related to diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting12,17,18,19, therefore the fecal microbiome may be a candidate risk factor that is both modifiable and easily accessible. For example, alpha diversity of the fecal microbiome is a within-subject measure of the number and relatedness of the microbes present in the gut. Higher alpha diversity is associated with better health outcomes in some disease contexts (e.g., diabetes)20,21, lower gastrointestinal distress20, and stability and resilience of the gut microbiome22,23. Alpha diversity is relatively stable in adults and is determined both by genetic factors, as well as modifiable environmental factors, such as diet, exercise, and medications20,24. Indeed, dietary intervention25, exercise26, and fecal microbial transplantation27 can all increase microbiome alpha diversity.

Here, we aimed to identify the extent to which gut-related markers could be used to predict the severity of gastrointestinal side effects after chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer patients. Participant factors (e.g., age, body mass index, tumor receptor status, surgery status, and diet) that related to the predictive markers and could be used to predict at-risk populations, were assessed next. Finally, secondary analyses assessed the potential mechanisms underlying the chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal side effects, including chemotherapy-induced gut microbiome disruption (i.e., reduction of microbial diversity and alterations in the microbial community), gastrointestinal inflammation28, and gastrointestinal permeability29.

Methods

Participants

Participants (n = 77) for a longitudinal observational parent study (The Intelligut Study) were recruited from The Ohio State University Stefanie Spielman Comprehensive Breast Center in Columbus, Ohio, USA11. This parent study assessed relationships among chemotherapy-induced gut disruption, inflammation, and cognitive impairment. Inclusion criteria included a recent diagnosis of stage IA—IIIB breast cancer with a treatment plan including anti-neoplastic chemotherapy. Exclusion criteria included a prior history of malignancy (excluding basal or squamous cell skin cancer), chemotherapy, cognitive impairment, or age above 80 years. Eighteen participants from the parent study were excluded from the current analyses due to the lack of a pre-chemotherapy fecal sample, resulting in a total of 59 subjects. Sociodemographics (age and menopausal status) and clinical variables (stage, treatment plan, receptor status, and body mass index [BMI]) from the medical chart were collected at baseline. Prescribed use of non-chemotherapy medications (intravenous or oral) that can impact the gut microbiome or inflammatory processes, including corticosteroids, antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, antidiarrheals, and antiemetics, were also extracted from the medical chart. Corticosteroids (dexamethasone and prednisone) were recorded for each individual timepoint if prescribed use was within 1 day of that timepoint. Antibiotics were noted if prescribed use was within 2 weeks of each timepoint. Proton pump inhibitors, antidiarrheals (Floranex, loperamide, and/or diphenoxylate-atropine), and antiemetics (ondansetron, palonosetron, aprepitant, fosnetupitant-palonosetron, and/or meclizine) were noted if prescribed use was within 1 month of each timepoint. Medications were considered taken when prescribed “as needed”. This study was approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki30. All participants provided informed consent.

Study design and procedure

Participants completed gastrointestinal symptom questionnaires and provided blood and fecal samples at 3 timepoints: at baseline (pre-chemotherapy), at the last chemotherapy infusion appointment (during chemotherapy, 60–253 days after baseline [mean ± SD: 100 ± 33]), and after a wash-out period (post-chemotherapy, 18–247 days after during chemotherapy timepoint [mean ± SD: 86 ± 48]). Fecal samples were collected, and questionnaires were completed within 3 days of the participants’ visits; blood samples were collected on the day of the visit in conjunction with a previously scheduled oncology appointment. Briefly, fecal samples were collected at home and frozen by the participants with a provided kit. The samples were kept frozen while being transported to the participant’s visit, partially defrosted and cut into aliquots in the lab, and then stored at −80 °C until analyses. Thus, any effects of the freeze-thaw were consistent among all samples. Participants received various chemotherapy regimens, all including taxane (either paclitaxel or docetaxel), with an average of 12.7 ± 6 infusions (range: 4–33). Other chemotherapeutics received included anthracyclines, cyclophosphamide, and/or carboplatin. The average time from the most recent chemotherapy infusion to the during chemotherapy timepoint was 16 ± 5 (range: 7–24) days and post-chemotherapy timepoint was 87 ± 46 (range: 28–247) days. If participants underwent surgery (n = 32 prior to study, n = 20 between during and post-chemotherapy visits) or radiation (n = 1 prior to study, n = 16 between during and post-chemotherapy visits) prior to or during the study, visits were completed at least 1 month after these events to minimize effects. Radiation has been reported to impact the intestinal microbiome31 and induce gastrointestinal side effects32, and thus may impact these outcomes at the post-chemotherapy timepoint only in these 16 subjects. In the current study, the change of the microbiome from baseline (pre-chemotherapy) to the post-chemotherapy timepoint was not impacted by radiation exposure as measured by 3 beta diversity measures and the microbial log-ratio (p > 0.05 for all). Furthermore, those who received radiation did not have higher levels of gastrointestinal symptoms at the post-chemotherapy timepoint. Indeed, those who received radiation actually had lower levels of diarrhea (p < 0.05). The post-chemotherapy timepoint was conducted at least 1 month after the completion of radiation, likely mitigating the effects of radiation on the microbiome and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Diet information

At baseline, participants were asked details about their typical diet for the previous year using the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ; Nutrition Quest, Berkley, CA, USA, Block 2000-Brief). Questionnaires were scored by Nutrition Quest and the data returned for analysis. Measures analyzed included daily calories, dietary fiber (g; from beans, fruits/vegetables, or grain), fat (g; saturated, monounsaturated, polyunsaturated, and trans), total sugar (g), calories from sugary beverages, and percent of calories from fat, protein, carbohydrates, sweets/desserts, and alcohol.

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Self-reported gastrointestinal symptoms were recorded using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Gastrointestinal Diarrhea (v1.0 – Short Form 6a) and Gastrointestinal Nausea and Vomiting (v1.0 – Short Form 4a). Both are validated tools to assess gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with cancer and gastrointestinal disease33,34,35. Participants completed these questionnaires electronically via REDCap in-person at their visit or at home via paper within 3 days of each timepoint. The Health Measures Scoring Service (HMSS) tool was used to convert the raw questionnaire data into validated T-scores based on a calibration population.

Blood samples and assays

Peripheral blood (8–10 mL) was collected via venipuncture at each timepoint and centrifuged (20 min at 1258 x g and 4 °C) to isolate plasma, which was stored at −80 °C until analysis. Intestinal permeability and inflammatory markers soluble cluster of differentiation 14 (sCD14; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA, cat: DC140) and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP; Hycult Biotech human LBP ELISA, Uden, Netherlands, cat: HK315) were measured in plasma samples36,37. Plasma samples were thawed on the day of the assay and run in duplicate with average intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variability (CVs) < 10%. The plasma samples for all 3 timepoints for each participant were measured on the same plate.

Fecal sample collection and processing

Fecal samples were collected as previously described11. Briefly, participants collected fecal samples at home within 3 days of their study visit using provided fecal collection kits. The participants stored the sample in a sealed insulated package with an ice pack in their freezer and brought it to their study visit for retrieval by the study team. All samples were kept at −80 °C until analyses were performed.

Intestinal inflammation marker calprotectin was measured in fecal samples from each timepoint via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) following the manufacturer’s protocol (Hycult Biotech Human Fecal Calprotectin, cat: HK382)38,39. All samples were run in duplicate with average intra- and inter-assay CVs both <10%. Calprotectin concentrations were analyzed as µg calprotectin/g fecal sample. Each participant’s fecal samples across all 3 timepoints were measured on the same plate, using the same standards for all timepoints for all the participants.

Microbiota sequencing and modeling

Microbiota sequencing and modeling data from the original study were used in these analyses11. Briefly, DNA extracted from fecal samples was used for library preparation and high-throughput sequencing by the Genomic Services Core at the Institute for Genomic Medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH. Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) 2.0 was used for amplicon processing, quality control, and taxonomic assignment. Samples were rarefied to 4,300 sequences per sample for all analyses. QIIME 2.0 was also used for beta diversity (weighted and unweighted UniFrac and Bray Curtis) and alpha diversity (Shannon entropy, observed operational taxonomic units [OTUs], and Faith’s phylogenetic diversity) analyses11.

A two-step process was used to identify baseline microbial taxa that may be related to chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms. First, the R package, DESeq240 was used to preliminarily identify potentially related taxa41. Specifically, the R packages qiime2R42 and phyloseq43 were used to import Qiime output.qza files for DESeq2 analysis. Baseline pre-chemotherapy amplicon sequence variants (ASV) were agglomerated at the phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels for analyses. The Wald test was used to assess the correlation of microbial taxa to the pre- to during chemotherapy change of diarrhea score, pre- to during chemotherapy change of nausea/vomiting scores, and the pre- to post-chemotherapy change of nausea/vomiting scores separately, and the DESeq2 program applied multiple corrections. As these analyses were used to identify potentially related taxa for predictive analyses, an unadjusted p value of 0.1 was used as a cut-off for inclusion in the predictive analyses. Second, linear mixed-effects models controlling for baseline gastrointestinal symptom level were used to more robustly test the relationship between these taxa and chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms (as described below).

Songbird v1.0.3 and Qurro were used for differential modeling of microbial taxa over chemotherapy treatment at the ASV level44,45. The log-ratio of the top 33% positively-associated ASVs (numerator) and the top 33% negatively-associated ASVs (denominator) was calculated to model significant changes in the relative abundance of microbial taxa as previously described11.

Data analysis strategy

Linear mixed-effects models were used to model changes in gastrointestinal symptoms, intestinal inflammation, and intestinal permeability markers over chemotherapy treatment (in separate models). Categorical time (pre-, during, and post-chemotherapy) was included as a fixed effect. All models included a random intercept for the participant to account for within-subject correlation over time, and models for individual permeability and inflammatory markers additionally included a random effect for the plate. Moderation of trajectories by medications and participant and treatment factors was performed by including each effect and its interaction with time in separate models. The Kenward-Roger adjustment to the degrees of freedom was used to control Type 1 error46.

To assess predictive relationships of pre-chemotherapy alpha diversity on outcomes over chemotherapy treatment, linear mixed-effects models were used. Specifically, during and post-chemotherapy measures of gastrointestinal symptoms, gut microbiome, and intestinal permeability and inflammation were the outcomes of individual models with pre-chemotherapy alpha diversity as the key predictor, while adjusting for pre-chemotherapy levels of the outcome. In addition, these models contained a fixed effect for time (during chemotherapy vs. post-chemotherapy) and the interaction of time with the pre-chemotherapy alpha diversity or microbial relative abundance level, allowing relationships to differ by time point. Secondary models also adjusted for baseline age, BMI, and menopausal status (pre- vs. post-), and chemotherapy regimen (taxane-based vs. taxane- and anthracycline-based). Analyses predicting during and post-chemotherapy gastrointestinal symptoms were completed first using the individual pre-chemotherapy alpha diversity measures (Supplementary Table 1). As the results of these analyses did not differ, alpha diversity measures were combined using z-scores into an alpha diversity composite score, as previously described11. This composite score was used for all analyses and throughout the Results section alpha diversity refers to this composite score. All analyses of fecal calprotectin used natural log-transformed values (ln). All analyses of sCD14 used values divided by 100,000 and LBP analyses used values divided by 100. For all models using beta diversity change, a pre-chemotherapy level could not be included as beta diversity is a point in 3D space rather than an individual value. Linear regression and linear mixed-effects models were used to assess the predictive relationships of individual microbial taxa for chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms. During chemotherapy diarrhea symptoms were the outcomes of individual models with pre-chemotherapy microbial relative abundance as the key predictor, while adjusting for pre-chemotherapy levels of diarrhea symptoms. As baseline microbial alpha diversity strongly related to nausea/vomiting symptoms post-chemotherapy, during and post-chemotherapy nausea/vomiting symptoms were the outcomes of individual models with pre-chemotherapy microbial relative abundance as the key predictor, while adjusting for pre-chemotherapy levels of nausea/vomiting symptoms. To determine pre-chemotherapy factors that modulated pre-chemotherapy alpha diversity and microbial relative abundance, independent sample t tests were used for categorical variables and Pearson correlations were used for continuous variables.

To assess mechanistic change relationships between microbiome, gastrointestinal symptoms, or intestinal permeability and inflammation, linear mixed-effects models were used. Specifically, during and post-chemotherapy measures of gastrointestinal symptoms were the outcomes of individual models with change scores of pre- to during chemotherapy microbiome measures or intestinal permeability or inflammation measures as the key predictors, while adjusting for pre-chemotherapy levels of the outcome and predictor. To assess cross sectional relationships, Pearson correlations were used.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 provides demographic and clinical information for the participants. On average, participants were 49 years old (SD: 11, range: 29–75) with a BMI of 29 (SD: 5.7, range: 18–42). Information on usage of other relevant medications (corticosteroids, antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, antidiarrheals, and antiemetics) is included in Supplementary Table 2. Briefly, these medications were prescribed “as needed” in a minority of subjects and potential usage varied by visit.

Chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms

This cohort experienced gastrointestinal side effects due to chemotherapy treatment, including diarrhea (p < 0.01, Fig. 1A) and nausea/vomiting (p < 0.01, Fig. 1B). Specifically, diarrhea increased from pre- to during chemotherapy (p < 0.001, Fig. 1A) and did not return to baseline levels post-chemotherapy. Nausea/vomiting symptoms also increased from pre- to during chemotherapy (p < 0.01, Fig. 1B), but returned to baseline levels post-chemotherapy. Neither chemotherapy-induced diarrhea nor nausea/vomiting related to 1) the time since the previous chemotherapy infusion, 2) the number of chemotherapy cycles, 3) the number of chemotherapy cycles per week, or 4) the total chemotherapy treatment time in weeks for either timepoint (p > 0.05 for all). Treatment with antidiarrheal, antiemetic, proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics, or corticosteroids did not prevent chemotherapy-induced diarrhea (Supplementary Fig. 1A–E) or nausea/vomiting (Supplementary Fig. 2A–E). In fact, the individuals prescribed antidiarrheals and antibiotics drove the increased diarrhea symptoms (Supplementary Fig. 1A, D), and in addition to antiemetics, drove the increased nausea/vomiting scores during chemotherapy (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B, D). Likely the individuals with greater rates or severity of diarrhea and nausea/vomiting were prescribed more antidiarrheal or antiemetic medications.

Trajectories of A diarrhea and B nausea/vomiting over chemotherapy treatment. Results shown are mean ± standard error from linear mixed-effects models. *p < 0.05.

Basal microbiome alpha diversity as a risk factor for chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms

The predictive relationships between pre-chemotherapy microbiome alpha diversity and chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms were assessed. Microbiome alpha diversity is a measure of how diverse the microbes are within one sample, considering the number of different taxa and their distribution. In step 1 non-covariate inclusive models, lower pre-chemotherapy microbiome alpha diversity predicted greater increases in diarrhea and nausea/vomiting over chemotherapy treatment. These relationships were driven by the during chemotherapy timepoint for diarrhea symptoms and the post-chemotherapy timepoint for nausea/vomiting symptoms (Table 2). This predictive relationship for diarrhea persisted after the inclusion of age, menopausal status, BMI, and chemotherapy regimen as covariates; trends for a similar predictive relationship to nausea/vomiting were observed after covariate inclusion (Step 2 models, Table 2). The relationships were not related to the duration between the last chemotherapy infusion and the during or post-chemotherapy timepoint for either gastrointestinal symptom (p > 0.05 for both). In addition, pre-chemotherapy microbiome alpha diversity was not related to any concurrent baseline gastrointestinal scores (p > 0.05 for both), indicating that alpha diversity specifically related to chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms.

Relationships between basal microbial taxa abundance and the development of chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms

As lower basal microbiome alpha diversity predicted chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms, the extent to which the relative abundances of specific microbial taxa predicted these chemotherapy side effects was assessed next. First, DESeq2 was used to identify baseline taxa potentially related to peak gastrointestinal symptoms (i.e., during chemotherapy). Baseline taxa potentially related to nausea/vomiting symptoms from pre-to post-chemotherapy were also identified, as baseline microbial alpha diversity specifically related to nausea/vomiting symptoms post-chemotherapy. Second, linear regression models were used to test the predictive value of those microbes for symptoms when controlling for baseline symptom levels. Five genera present at baseline, Faecalibacterium, Lachnospiraceae FC020 group, Lachnospira, and UCG 005, all in the phylum Firmicutes and class Clostridia, negatively related to the severity of diarrhea symptoms, meaning lower baseline relative abundance of these taxa predicted greater chemotherapy-induced diarrhea symptoms (p < 0.05 for all, Supplementary Table 3). The class Bacilli and order Lactobacillales (both in the phylum Firmicutes) positively predicted the development of diarrhea symptoms (p < 0.05 for both, Supplementary Table 3). Furthermore, only one taxon, the genus Tyzzerella (phylum: Firmicutes, class: Clostridia), significantly related to the severity of nausea/vomiting symptoms both during and post-chemotherapy (p < 0.05, Supplementary Table 4). Tyzzerella was positively related to the severity of nausea/vomiting symptoms, meaning higher basal relative abundance of Tyzzerella predicted greater chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting symptoms. The phylum Euryarchaeota and associated genera Methanobrevibacter, as well as the family Christensenellaceae (phylum: Firmicutes, class: Clostridia), significantly negatively predicted nausea/vomiting symptoms specifically during chemotherapy (Supplementary Table 4).

Relationships between participant characteristics and basal microbiome alpha diversity or chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms

As baseline microbiome alpha diversity and specific microbes predicted chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms, participant characteristics associated with these baseline microbiome measures were investigated next. Several of the assessed participant variables (tumor pathology, surgery status, and diet) were significantly related to baseline microbiome alpha diversity and specific microbe relative abundances (Table 3, Supplementary Table 5). First, participants with HER2+ breast tumors had significantly lower baseline alpha diversity (p < 0.0001, Fig. 2A) and the Lachnospiraceae FC020 group (p < 0.01, Supplementary Table 5) than those with HER2- breast tumors. Given that both of these microbiome factors associated with worse gastrointestinal side effects, it was not unexpected that HER2+ participants also reported greater levels of diarrhea (HER2 effect: p < 0.0001, HER2 × time: p < 0.01, Fig. 2B) and nausea/vomiting (HER2 effect: p < 0.001, Fig. 2C) over chemotherapy treatment relative to HER2- participants. Second, participants who still had their primary tumor intact (neoadjuvant) at baseline had significantly lower microbiome alpha diversity (p < 0.0001, Fig. 2D) and Lachnospiraceae FC020 group (p < 0.05, Supplementary Table 5) than those who had already undergone tumor removal surgery (adjuvant). Thus, as anticipated, neoadjuvant participants reported more nausea/vomiting symptoms over chemotherapy treatment (surgery status effect: p < 0.05, Fig. 2F), although this moderation was not significant for diarrhea symptoms (p > 0.05, Fig. 2E). Notably, HER2+ participants were more likely to also be neoadjuvant (HER2+ adjuvant treatment n = 7, HER2+ neoadjuvant treatment n = 14). Indeed, the interaction between HER2 and surgery status (p < 0.05) related to lower baseline microbiome alpha diversity.

A Baseline alpha diversity composite of HER2- and HER2+ participants. Trajectories of (B) diarrhea symptoms and (C) nausea/vomiting symptoms of HER2 negative and positive participants. D Baseline alpha diversity composite of adjuvant and neoadjuvant participants. Trajectories of (E) diarrhea symptoms and (F) nausea/vomiting symptoms of adjuvant and neoadjuvant participants. Baseline alpha diversity composite compared via independent sample t-tests. Trajectory results shown are mean ± standard error from linear mixed-effects models. *p < 0.05.

Relationships between participant diet and basal microbiome alpha diversity or chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms

Participant diet variables also related to the baseline microbiome characteristics that were predictive of gastrointestinal side effects of chemotherapy. Higher percentages of daily calories from carbohydrates (p < 0.05, Fig. 3A) and specifically sugary beverages (p < 0.05, Fig. 3D) at baseline were each associated with lower baseline microbiome alpha diversity, as expected20,47. Neither diarrhea nor nausea/vomiting were moderated by the percent of calories from carbohydrates (p > 0.05 for all, Fig. 3B, C), suggesting an indirect relationship to gastrointestinal chemotherapy side effects. In contrast, higher calories from sugary beverages were associated with greater diarrheal symptoms overall (main effect: p < 0.05, Fig. 3E), but not nausea/vomiting (p > 0.05, Fig. 3F). Other relevant diet characteristics assessed, including total daily calories, total fiber, total sugar, and percent calories from fat, protein, and sweets/desserts, were not related to alpha diversity (p > 0.05 for all, Table 3, Supplementary Table 6).

A Correlation of baseline dietary carbohydrates (as a percent of overall daily calories) and baseline alpha diversity. Trajectories of (B) diarrhea symptoms and (C) nausea/vomiting symptoms of those with low, medium, and high dietary carbohydrates. D Correlation of baseline daily calories from sugary beverages and baseline alpha diversity. Trajectories of (E) diarrhea symptoms and (F) nausea/vomiting symptoms of those with low and high daily calories from sugary beverages. Correlations determined via Pearson correlations. Trajectory results shown are mean ± standard error from linear mixed-effects models. *p < 0.05.

Basal microbiome alpha diversity predicts changes in potential mechanisms of gastrointestinal symptoms (microbial disruption, intestinal permeability and inflammation) over chemotherapy

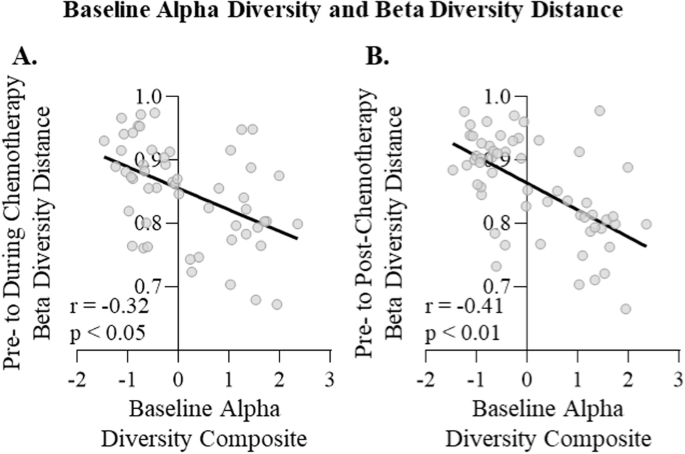

As baseline microbiome alpha diversity predicted chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms, the extent to which alpha diversity also predicted changes in various hypothesized mechanisms of these symptoms (microbial disruption, intestinal permeability and inflammation) was examined next. Indeed, reductions in gut microbiome diversity and microbial relative abundances over chemotherapy have been previously reported to relate to gastrointestinal symptoms12,48. Thus, initial analyses determined if lower baseline microbiome alpha diversity predicted greater chemotherapy-induced disruption of the gut microbiome. In step 1 models without covariates, lower basal microbiome alpha diversity was associated with a greater shift of gut microbial relative abundances (Table 4) and overall community structure (as measured by Bray Curtis beta diversity distance) (Table 4, Fig. 4A, B) both during and post-chemotherapy. Of note, other beta diversity measures (unweighted and weighted UniFrac) were not related to baseline alpha diversity (data not shown). Relationships were largely robust to covariate (age, menopausal status, BMI, and chemotherapy regimen) inclusion, with the single exception of the differential microbes at the during chemotherapy time point. Altogether, lower gut microbiome alpha diversity prior to chemotherapy predicted greater changes in the gut microbiome over chemotherapy treatment.

Relationship of baseline alpha diversity composite to Bray Curtis beta diversity distance from (A) pre- to during chemotherapy treatment and (B) pre- to post-chemotherapy treatment determined via Pearson correlation.

Chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms have also been associated with intestinal permeability and inflammation49,50. Therefore, the relationships between baseline microbiome alpha diversity and changes in markers of intestinal permeability (plasma soluble cluster of differentiation 14 [sCD14] and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein [LBP]) and intestinal inflammation (fecal calprotectin) over chemotherapy were then investigated. Of note, the gut microbial composition contributes to both intestinal permeability and inflammation51. Here, chemotherapy increased circulating sCD14 (p < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 3A), but did not alter circulating LBP, the ratio of LBP to sCD14, or fecal calprotectin (p > 0.05 for all, Supplementary Fig. 3B, C, D). Furthermore, lower pre-chemotherapy microbiome alpha diversity predicted an increase of circulating sCD14 during chemotherapy (Step 1 models, Table 5), which was robust to the inclusion of age, menopausal status, BMI, and chemotherapy regimen as covariates (Step 2 models, Table 5). This suggests that baseline alpha diversity selectively predicted an increase in one gut permeability marker over chemotherapy, but not other intestinal permeability or inflammation markers (LBP, LBP/sCD14 ratio, or fecal calprotectin, Table 5).

Relationships between changes in these potential mechanisms and changes in gastrointestinal symptoms over chemotherapy

In corroboration with previous studies of gastrointestinal symptoms17, greater changes in beta diversity from pre- to during chemotherapy was associated with an increase in diarrhea symptoms with chemotherapy. This effect was driven by the relationship with during chemotherapy diarrhea symptoms for unweighted UniFrac (estimate: 20.1, SE: 8.7, p < 0.05), weighted UniFrac (estimate: 47.1, SE: 14.4, p < 0.01), and Bray Curtis (estimate: 23.4, SE: 13.4, p < 0.01), as the only significant relationship with post-chemotherapy diarrhea symptoms was weighted UniFrac (estimate: 29.5, SE: 14.8, p < 0.05). A greater shift in the chemotherapy-associated gut microbial relative abundance was also associated with an increase of diarrhea symptoms over chemotherapy, which was stronger during chemotherapy (estimate: 2.6, SE: 1.2, p < 0.05) than post-chemotherapy (estimate: 1.5, SE: 1.3, p > 0.05). In contrast, nausea/vomiting symptoms were neither related to changes in beta diversity nor relative abundance with chemotherapy (p > 0.05 for all).

Furthermore, neither changes in intestinal permeability nor inflammation markers were related to changes in diarrhea during or post-chemotherapy (p > 0.05 for all). In contrast, the increase in circulating sCD14 with chemotherapy was positively related to the nausea/vomiting symptoms during chemotherapy (estimate: 0.64, SE: 0.29, p < 0.05), but not post-chemotherapy (estimate: 0.05, SE: 0.29, p > 0.05). This relationship did not exist for changes in other intestinal markers (LBP, fecal calprotectin, or the LBP/sCD14 ratio; p > 0.05 for all), although cross-sectionally, elevated LBP was also associated with higher nausea/vomiting symptoms during chemotherapy (r = 0.28, p < 0.05).

Discussion

The primary goal of the current study was to investigate the potential for basal gut microbiome characteristics to be risk factors for subsequent chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal side effects, as the microbiome is clinically accessible and potentially modifiable. Multiple previous studies have instead observed a cross-sectional relationship between the gut microbiome and gastrointestinal symptoms during chemotherapy12,19,48. For example, in breast cancer patients, reduced alpha diversity during chemotherapy is associated with diarrhea and nausea12,48. In the current study, a predictive relationship was observed for the first time, such that lower baseline (pre-chemotherapy) microbial alpha diversity predicted greater symptoms of diarrhea and nausea/vomiting over chemotherapy treatment.

Our initial analyses used three individual alpha diversity measures, which all followed the same predictive patterns as a composite score that combined all three, indicating that the relationship between pre-chemotherapy alpha diversity and chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms is not specific to microbial richness or evenness, but rather overall alpha diversity. A similar predictive relationship was reported in one study of radiotherapy-induced diarrhea in a mixed cancer patient population52. This same study also found that a lower relative abundance of the genus Faecalibacterium was predictive of radiotherapy-induced diarrhea52, similar to the present findings with chemotherapy. Of note, pre-chemotherapy alpha diversity was only related to gastrointestinal symptoms with chemotherapy treatment; the measure did not relate to baseline gastrointestinal symptoms, indicating that the relationship was dependent on chemotherapy treatment. Furthermore, the relationship between pre-chemotherapy microbiome diversity and gastrointestinal symptoms may be time-dependent. Specifically, lower pre-chemotherapy microbiome diversity was related to greater diarrhea during chemotherapy and greater nausea/vomiting several months after chemotherapy was complete (post-chemotherapy). Additional studies are necessary to corroborate how time-dependent these relationships are. Overall, these findings suggest that approaches directed at increasing alpha diversity before planned chemotherapy infusions may improve the side effects that can precipitate chemotherapy dose reductions and cessation. Some of these approaches may be dietary interventions25,53,54, exercise26, decreasing stress55,56, or gut-directed therapies (e.g., fecal microbial transplant)57,58.

Furthermore, the present findings, that decreased baseline relative abundance of certain microbial taxa (e.g., Faecalibacterium) were associated with increased severity of chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms, warrant further investigation to determine if efforts to bolster these specific taxa (e.g., prebiotic/probiotic interventions) may alleviate or prevent chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms. The previous scant studies in breast cancer cohorts were not able to test predictive relationships due to their cross-sectional nature and often only utilized general diversity measures, not taxonomic differences or changes12,35,48. In one study that assessed taxonomic differences, microbes in the family Ruminoccaceae negatively related to diarrhea during chemotherapy12, but was not identified as a predictive microbe in the current study. However, another study of mixed cancer types within 5 years of chemotherapy treatment demonstrated that taxa in the family Lachnospiraceae and genus Faecalibacterium negatively related to diarrhea symptoms, similar to the predictive findings in the current study35. Additional research incorporating pre-chemotherapy microbiome analyses are warranted.

Many of the predictive taxa identified in the current study were in the phylum Firmicutes, class Clostridia, and orders Lachnospirales and Oscillospiralles, which commonly produce short-chain fatty acids, indicating a potential mechanism by which chemotherapy effects on these microbes could induce gastrointestinal symptoms59,60. Another potential mechanism relates to reactive oxygen species, known to play a role in chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicity61. Certain microbes we identified are involved in the regulation of reactive oxygen species, including Faecalibacterium, Lachnospiraceae, and Clostridia62. While our preliminary analyses of intestinal inflammation and permeability did not relate to gastrointestinal symptoms, some of the identified microbes have anti-inflammatory effects (e.g., Faecalibacterium)63 as well as promote intestinal barrier integrity (e.g., Lachnospiraceae)64. These potential mechanisms warrant further investigation.

Analyses to identify participant factors that influenced the baseline microbiome alpha diversity revealed that some common factors known to influence alpha diversity, including age65 and body mass66, were not significantly associated with alpha diversity in the current study. The lack of effect of age is potentially due to a combination of the wide range of ages included in the present study (29–74 years old) and the medium sample size. A larger sample size may also be necessary to observe the previously reported relationship between BMI and alpha diversity. Remarkably, breast tumor HER2 positivity was associated with lower pre-chemotherapy levels of microbial alpha diversity. While few other studies have assessed the impact of breast cancer molecular subtype on the fecal microbiome, three have reported differences between the fecal microbiome of HER2+ and HER2- breast cancer patients prior to chemotherapy treatment67,68, one of which included a similar decreased alpha diversity in HER2+ patients69. The present participants with HER2+ breast cancer experienced greater diarrhea and nausea/vomiting symptoms at all timepoints (i.e., even before chemotherapy), as well as a greater increase in diarrhea symptoms during chemotherapy relative to those with HER2- tumors. Indeed, cancer patients report gastrointestinal symptoms even prior to treatment initiation70, indicating potential effects of tumors and/or the stress of a cancer experience on gut symptomology. In the current study, these pre-chemotherapy symptoms were not related to microbiome alpha diversity for participants with either HER2+ or HER2- breast cancer. Furthermore, 65% of HER2+ patients require a dose reduction or delay due to treatment toxicity71 as the chemotherapy regimens used for treatment of this cancer subtype are notorious for the severity of gastrointestinal symptoms3. The present medium-sized cohort did not allow for analyses by chemotherapy regimen, warranting further investigation.

Basal alpha diversity was also lower in those participants with their primary tumor intact (i.e., neoadjuvant treatment), who also reported higher levels of nausea/vomiting than adjuvant patients regardless of chemotherapy treatment (i.e., over all timepoints). The pre-chemotherapy gastrointestinal symptoms were unrelated to microbiome alpha diversity for both adjuvant and neoadjuvant participants. Another study in breast cancer patients also reported that pre-chemotherapy fecal samples of adjuvant and neoadjuvant patients differ by relative abundance of specific microbes, in the absence of alpha/beta diversity differences12. Notably, this study only included post-menopausal patients with ER + /HER2- breast cancer and the sample of neoadjuvant participants was small (n = 18). In contrast, the current study included both pre- and post-menopausal participants with a range of breast cancer molecular subtypes. In colorectal cancer, notably a tumor within the gastrointestinal tract, tumor removal surgery does not reverse cancer-associated microbiome disruption even 1 year after surgery as compared to healthy controls even when accounting for chemotherapy treatment72, suggesting lingering microbiome changes due to a tumor. Of note, while HER2+ patients are more likely to receive chemotherapy neoadjuvantly71, both HER2 and surgery status independently related to lower microbiome alpha diversity in the present study. Overall, these results suggest that the presence of a breast tumor, especially a HER2+ tumor, may reduce microbiome diversity prior to chemotherapy. Indeed, in a mouse breast tumor model, mammary tumors similarly decrease microbiome diversity, which remains altered several weeks after tumor resection73.

In addition to tumor characteristics, two of the assessed dietary factors also related to lower baseline microbiome alpha diversity: higher daily calories from carbohydrates and sugary beverages, specifically. Higher calories from carbohydrates47 and sugary beverages20 are associated with lower microbiome diversity outside of the cancer context. Furthermore, diets high in sugar can exacerbate diarrhea74. These findings suggest that dietary interventions (e.g., reduction of sugar intake) may be one approach to increase alpha diversity before chemotherapy in order to prevent or lessen subsequent gastrointestinal symptoms due to chemotherapy. Dietary considerations are often missing from microbial analyses in the current chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms literature, particularly in human studies, as these data are difficult to collect and incorporate. While only two of the assessed dietary measures from the present study were related to the decreased alpha diversity prior to chemotherapy, future studies should consider in-depth pre-chemotherapy diet analyses combined with microbial and gastrointestinal symptoms analysis. Future work may also assess micronutrients, dietary variety, and intake of vegetables and fruits as these are related to microbiome alpha diversity20. These data would better allow for the development of dietary recommendations both prior to and during chemotherapy to reduce chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms. Indeed, current recommendations are to eat small frequent meals with bland foods, increased fiber intake, and avoid dietary triggers75,76. Most of the dietary interventions research in chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal side effects is focused on individualized dietary plans with registered dieticians. These studies have shown some promise in reducing these debilitating side effects77,78, but are difficult to generalize to the numerous cancer patients receiving chemotherapy.

As lower basal microbiome alpha diversity predicted greater chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms, we hypothesized that lower microbiome diversity prior to chemotherapy may also predict greater chemotherapy-induced changes of the microbial community, one biological mechanism of these symptoms12,19. Indeed, in our analyses, lower alpha diversity prior to chemotherapy predicted greater chemotherapy-associated shifts in the gut microbial community over chemotherapy. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to show this relationship in patients with cancer. Moreover, the magnitude of these shifts in the microbial community were associated with greater severity of chemotherapy-induced diarrhea. These results indicate that lower microbiome diversity prior to chemotherapy predisposes patients to greater chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal side effects potentially via exacerbated changes to the gut microbial community structure. Of note, these analyses cannot distinguish if the changes in the microbial community are driving the gastrointestinal side effects or if the gastrointestinal side effects are driving the microbial community changes79,80.

Previous studies have reported that chemotherapy transiently increases intestinal inflammation and permeability, which are associated with gastrointestinal side effects19,29,50. While intestinal permeability can be directly measured by assessing the absorption of different sugars81, circulating levels of molecules important for the recognition of bacterial products (e.g., LBP and sCD14) can be used as indirect markers of microbial translocation37,82, a downstream consequence of intestinal permeability36. While sCD14 is related to intestinal permeability, sCD14 is also known to increase with general systemic inflammation, whereas LBP is a more specific marker of microbial translocation36. In the current cohort of breast cancer patients, chemotherapy increased sCD14, but not LBP. These results suggest that the chemotherapy-induced increase in sCD14 in this cohort may reflect the previously reported systemic inflammation11 more than increased intestinal permeability. The lack of a chemotherapy-induced increase in intestinal permeability in this cohort may be due to the use of these indirect measures as opposed to the more sensitive, conventional measurements of sugar absorption83 or because permeability markers transiently increased more acutely after chemotherapy treatment29. Here, chemotherapy also did not significantly increase fecal calprotectin, a marker of intestinal inflammation49. Even though chemotherapy has previously been reported to increase fecal calprotectin acutely19, this effect is not universally observed84 potentially due to chemotherapy-induced neutropenia as fecal calprotectin is released by neutrophils85 or due to the collection of the fecal samples several weeks after the most recent chemotherapy infusion.

As intestinal inflammation and permeability are potential mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal symptoms49,50, their relationship with microbiome alpha diversity was also assessed. Lower microbiome alpha diversity prior to chemotherapy treatment predicted greater increases of circulating sCD14, but not other intestinal permeability or inflammation markers. To our knowledge, the relationship between pre-chemotherapy microbiome diversity and chemotherapy-induced changes of intestinal permeability and inflammatory markers has not been assessed previously. Increases of sCD14 with chemotherapy were related to chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting, suggesting that the inflammation predicted by lower pre-chemotherapy alpha diversity could be playing a role in chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting86,87.

Existing research on the potential for gut-directed interventions (e.g., probiotics, fecal microbial transplant) to ameliorate chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal side effects has been inconclusive. Some studies and meta-analyses demonstrate that probiotics ameliorate diarrhea88, nausea, and vomiting89, while others suggest little to no benefit90,91,92. The current study indicates that certain cancer types or modifiable characteristics, such as diet, may be risk factors for low microbial alpha diversity, which consistently predicts subsequent gastrointestinal side effects of chemotherapy. Thus, these groups of patients may benefit most from gut-directed therapeutics prior to chemotherapy initiation (e.g., diet modification, microbial transplant) in order to minimize dose reductions or cessation of chemotherapy.

Responses