Bias recognition and mitigation strategies in artificial intelligence healthcare applications

Introduction

As of May 13, 2024, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) update indicated an unprecedented surge in the approval of AI-enabled Medical Devices, listing 191 new entries while reaching a total of 882, predominantly in the field of radiology (76%), followed by cardiology (10%) and neurology (4%)1. These approvals reflect AI’s growing role in healthcare, including applications such as analyzing medical images, monitoring health metrics through wearable devices, and predicting outcomes from Electronic Medical Records. This illustrates the rapid growth of AI technologies to improve and personalize patient care, not only in the field of medical imaging and diagnostics but across all aspects of healthcare delivery. This growth has been driven by the unique adeptness of AI models to navigate large healthcare datasets and learn complex relationships with reduced processing speed, enabling superior task performance compared to traditional statistical methods or rule-based techniques. However, these models can and have gained complexity, presenting challenges distinct from those encountered by simpler or traditional statistical tools. Specifically, deep learning (DL) models are commonly opaque (i.e., black-box) in nature, lacking explainability or a clear identification of features that influence model performance, thus limiting opportunities for human oversight or an evaluation of biological plausibility2.

Central to these challenges is the issue of bias, which can manifest itself in numerous forms to exacerbate existing healthcare disparities. Regulatory bodies, including the European Commission, FDA, Health Canada, the World Health Organization (WHO), have intensified their efforts to establish stricter frameworks for the development and deployment of AI in healthcare, recognizing a critical need to uphold the core principles of fairness, equity, and explainability3,4,5,6,7. Such frameworks aim to systematically identify and mitigate bias to ensure that AI models adhere to ethical principles and do not perpetuate or amplify historical biases or discrimination against vulnerable patient populations.

This comprehensive narrative review delves into the unique types of bias commonly encountered in AI healthcare modeling, explores their origins, and offers appropriate mitigation strategies. We begin by highlighting the central role that bias mitigation plays in achieving fairness, equity, and equality for healthcare delivery. This is followed by a detailed review of where and how bias can introduce itself throughout the AI model lifecycle and conclude with strategies to quantify and mitigate bias in healthcare AI.

Methods

We followed a critical review methodology to objectively explore and consolidate literature related to AI bias in healthcare8. Our review focused on English articles published from 1993 to 2024, sourced from databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and publisher platforms like Elsevier. To refine our search, Boolean operators were used, combining keywords inclusive of “Medical AI,” “Healthcare AI,” “AI bias,” “AI ethics,” “Responsible AI,” “Healthcare disparities,” “Fairness in medical AI,” “Equity, equality, and fairness in healthcare,” “Bias mitigation strategies in AI,” “Algorithmic bias,” “AI model life cycle,” and “Data diversity.” Each specific type of bias in AI (e.g., selection bias, representation bias, confirmation bias, etc.) was also searched. Additionally, reference lists from selected articles were examined to identify further relevant studies on bias in healthcare AI applications. Studies offering differing perspectives or contradictory evidence were carefully selected to ensure a balanced and comprehensive view of bias in healthcare AI.

We included studies published within a broad timeframe to capture both historical and contemporary perspectives on fairness, equity, and bias in healthcare AI. Incorporating foundational references, such as a 1993 publication on equity and equality in health9 was crucial, as these concepts form the basis for understanding and evaluating fairness in contemporary AI applications.

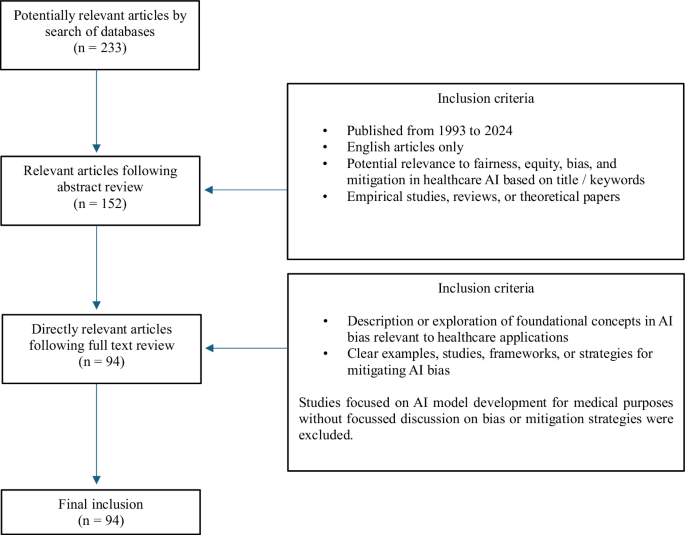

Our search yielded 233 potentially relevant articles. After initial screening of titles and abstracts, this was narrowed down to 152 articles with direct relevance to AI bias in healthcare. Following thorough full-text review, 94 articles were selected for our final review, as shown in Fig. 1. We employed a thematic-based approach to identify and categorize recurring themes, patterns, and insights related to bias types and mitigation strategies.

This figure illustrates the process used to filter and review literature from 233 initial articles, narrowing down to 94 articles that directly explored AI bias and mitigation strategies in healthcare.

Bias

In the context of healthcare AI, bias can be defined as any systematic and/or unfair difference in how predictions are generated for different patient populations that could lead to disparate care delivery10. Through this, disparities related to benefit or harm are introduced or exacerbated for specific individuals or groups, eroding the capacity for healthcare to be delivered in a fair and equitable manner11. The concept of “bias in, bias out”, a derivative of the classic adage “garbage in, garbage out,” is often implicated when AI model failures are observed in real world settings12, highlighting how biases within training data often manifest as sub-optimal AI model performance out in the wild13. However, bias may be introduced into all stages of an algorithm’s life cycle, including their conceptual formation, data collection and preparation, algorithm development and validation, clinical implementation, or surveillance. This complexity is compounded by the inadequacy of methods for routinely detecting or mitigating biases across various stages of an algorithm’s life cycle, emphasizing a need for comprehensive and holistic bias detection frameworks14,15.

In 2023 Kumar, et al., conducted a study systematically evaluating the burden of bias in contemporary healthcare AI models14. Using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) selection strategy16, a standardized methodology to estimate risk of bias (ROB), they sampled 48 studies distributed across tabular, imaging, and hybrid data models. They reported that 50% of these studies demonstrated a high ROB, often related to absent sociodemographic data, imbalanced or incomplete datasets, or weak algorithm design. Only 20%, or 1 in 5 studies were considered to have a low ROB. A similar study, performed by Chen, et al., using the PROBAST (Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool) framework17 (For further details, refer to Supplementary Table 1), examined 555 published neuroimaging-based AI models for psychiatric diagnosis, identifying only 86 studies (15.5%) included external validation while 97.5% included only subjects from high-income regions. Overall, 83% of studies were rated at high ROB18. These studies emphasize a critical need for improved awareness of bias in healthcare AI, and the routine adoption of mitigation strategies capable of bridging model conception through to fair and equitable clinical adoption.

Fairness, Equality and Equity

Fairness, equality, and equity are core principles of healthcare delivery that are directly influenced by bias. Fairness in healthcare encompasses both distributive justice and socio-relational dimensions, requiring a holistic consideration of each individual’s unique social, cultural, and environmental factors, these going beyond the concept of equality – which aims to ensure equal access and outcomes19,20. Equity recognizes that certain groups may require tailored resources or support to attain comparable health benefits9. Navigating these nuances and potential trade-offs between core principles is essential, as blanket approaches to fairness may inadvertently reinforce existing disparities21.

Defining and measuring fairness metrics, such as demographic parity, equalized odds, equal opportunity, and counterfactual fairness, is a complex challenge that requires a deep understanding of the healthcare context as well as the lived experiences of diverse patient populations. Failure to apply these metrics appropriately can lead to unintended consequences that may undermine the ethical foundations of equitable care, such as perpetuating healthcare disparities, misallocating resources, or reinforcing systemic biases that disproportionately impact vulnerable populations22.

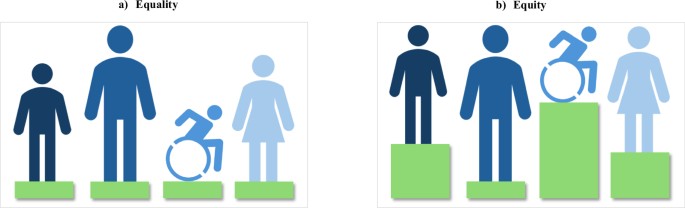

Differentiating equality from equity is essential to understanding the influences that AI bias can impose on healthcare disparities. These often-competing principles, as illustrated in Fig. 2, must be iteratively considered to achieve the best possible balance9,23.

This figure illustrates the key differences between Equality and Equity in healthcare support. It presents two scenarios: a “Equality” is depicted where each individual, regardless of their needs, receives the same level of support, symbolized by equal height green platforms for all figures. b “Equity” is shown where supports are varied according to individual needs, represented by green platforms of different heights, ensuring that each person reaches the support they need. This visualization underscores the importance of tailoring healthcare resources to address specific needs to achieve true equity.

Types of Bias

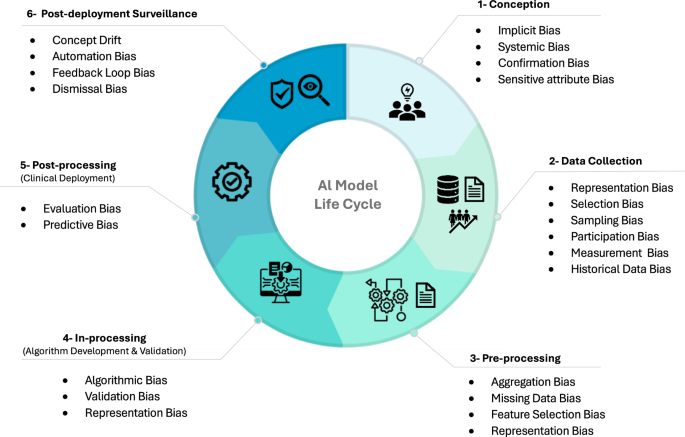

In the following sections, we explore the various forms of bias commonly encountered in healthcare AI. Our discussion, supplemented by relevant examples, has been structured to consider biases introduced from; (i) human origin; (ii) algorithm development; and (iii) algorithm deployment that may exist within each stage of the AI model lifecycle. A graphical illustration of these stages is provided in Fig. 3.

This figure maps the stages of the AI model life cycle in healthcare, highlighting the common phase at which biases can be introduced. The AI life cycle is divided into six phases: conception, data collection, pre-processing, in-processing (algorithm development and validation), post-processing (clinical deployment), and post-deployment surveillance. Each phase is prone to specific biases that can affect the fairness, equity, and equality of healthcare delivery.

Human Biases

The dominant origin of biases observed in healthcare AI are human. While rarely introduced deliberately, these reflect historic or prevalent human perceptions, assumptions, or preferences that can manifest across various future stages of AI model development, potentially with profound impact24. For example, data collection activities influenced by human bias can lead to the training of algorithms that replicate historical healthcare inequalities, leading to cycled reinforcement where past injustices are perpetuated into future practice25. The different types of human biases that can be introduced are discussed below and summarized in Table 1.

Implicit bias

Implicit bias occurs when subconscious attitudes or stereotypes about a person’s or group’s characteristics, such as birth sex, gender identity, race, ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status, become embedded in how individuals behave or make decisions. This can present surreptitious but powerful influences on medical AI systems trained from these decisions, particularly when features contributing to this bias are not routinely captured by training data26. This is commonly the case for patient self-reported characteristics, such as gender identity and ethnicity (referring to shared cultural practices, perspectives, and beliefs) that are commonly absent from or inconsistently coded by Electronic Health Records (EHR)27.

Systemic bias

Systemic bias represents an important dimension of human bias. While related to implicit bias, systemic bias extends to encompass broader institutional norms, practices, or policies that can lead to societal harm or inequities. The origins of systemic bias are more structural in nature and act at higher societal levels than implicit bias, often requiring modification in legislation or institutional policies to address28,29. For example, systemic bias may manifest as inadequate medical resource funding for un-insured individuals, underserved communities, or racial and ethnic minority groups, while implicit bias may be observed in a clinician’s own subconscious assumptions about a patient’s capacity to comply with medical care based on a stereotype.

Confirmation bias

It is important to recognize that human biases can provide influence beyond the contamination of training data. How each model is conceived and designed, and how it is ultimately used or monitored in clinical practice may similarly be influenced by human implicit or systemic biases. During model development, developers may consciously or subconsciously select, interpret, or give more weight to data that confirms their beliefs, overemphasizing certain patterns while ignoring other patterns that don’t fit expectations. This form of human-mediated bias is called confirmation bias30,31.

How human biases change over time is an important consideration given strong dependencies on the use of large-scale historic training data that are accrued over extended periods of time. While implicit and systemic biases shift with societal influence, models trained from historical data may inadvertently re-introduce unwanted biases into contemporary care. For example, older datasets influenced by an ethnicity bias may lead to AI models that generate skewed predictions across minority groups, despite more inclusive contemporary ideologies. This results in training-serving skew, where shifts in bias alter data distributions between the time of training and model serving32. A similar temporally sensitive bias, known as “Concept shift,” can occur due to changes in the perceived meanings of data. How clinicians perceive and code diseases or outcomes can change dynamically over time, introducing a unique, human-level bias surrounding what data means and is being used for. Addressing this bias can be challenging, requiring involvement from clinicians with experience spanning these shifting practice periods. Effort must be undertaken to ensure awareness of historical data that contains outdated practices, underrepresented groups, or past healthcare disparities not representing current real-world scenarios33.

Data bias

Beyond human influences, numerous additional biases can be introduced to data used in AI model training, altering its representation of the target environment or population and leading to skewed or unfair outcomes34. A summary of biases introduced during data collection are provided in Table 2.

Representation bias

Representation bias describes a lack of sufficient diversity in training data and is a dominant form of bias limiting the generalizability of healthcare AI models into unique environments or populations25. This bias can arise from an underlying implicit or systemic bias in the healthcare system or a history of underrepresentation for a minority group, either directly or indirectly from a reluctance to share information or participate in clinical trials35,36,37. These factors can lead to historical gaps in healthcare data, which can now be projected forward into AI healthcare models. For example, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) trained from large chest X-ray datasets sourced from academic healthcare facilities have been shown to underdetect disease in specific patient populations, inclusive of females, Black, Hispanic, and patients of low socioeconomic status38.

Selection and sampling bias

Representation bias can also be established through selection or sampling bias. Selection bias occurs when the process of how data is chosen or collected inadvertently favors certain groups or characteristics, leading to a non-representative sample. An example of this is the “healthy volunteer” selection bias observed in the UK Biobank, where participants are generally healthy and therefore do not represent patients typically encountered by healthcare systems39. Sampling bias is a form of selection bias resulting from non-random sampling of subgroups, establishing data patterns that are non-generalizable to new populations. Participation bias or self-selection bias are also strong contributors to representation bias in research generated datasets. For example, patients who are sicker, have higher comorbidity, or are unable to participate in longitudinal research protocols for geographic or economic reasons may not be represented10.

Measurement bias

Large scale data resources required for AI model development and validation are often sourced from multiple hospital sites, each with unique methods of data acquisition. Such variations are often not related to biological factors, rather are related to differences in data acquisition or processing. These measurement biases result in systematic differences that alter the representation of variables, being most commonly encountered in medical diagnostics33. In radiology, for example, imaging hardware manufacturer, model, software versions and acquisition parameters all meaningfully alter the characteristics of diagnostic images40. Similarly, in pathology, variations in tissue preparation, staining protocols, and scanner-specific parameters can impact the data used in cancer-diagnostic tasks41. AI models can inadvertently learn patterns associated with these non-biological variations, causing them to deviate from their primary objective of diagnosing medical conditions. In contrast, models trained from only one data source, adhering to a consistent set of acquisition parameters, may underperform when applied to data from another source34.

Algorithmic bias

Algorithmic biases can be considered as those inherent to the pre-processing of a training dataset or during the conceptual design, training, or validation phases of an algorithm. They can stem from the inappropriate selection of non-diverse datasets, features, or selection of algorithm processes set by model developers34. These biases, along with examples, are further detailed in Table 3.

Aggregation bias

A type of algorithmic bias strongly impacting model generalizability is aggregation bias, which occurs during the data preprocessing phase10. Data aggregation is the act of transforming patient data into a format more suitable for algorithm development, including imputing missing values, selecting key variables, combining data from various sources, or engineering new data features. When population data is merged to form a common, model-ready input, biases can emerge through the selection of input features that are maximally available across all subjects, establishing a “one-size-fits-all” approach42. One example of this bias is managing missing or outlier values, such as patient weight. This variable may not be available for certain patients with disabilities, particularly those using wheelchairs, or may be under-representative for those with limb amputations or terminal illnesses43. Models trained using aggregate data may mistakenly assume uniformity across diverse patient groups, may impute missing variables, and inherently overlook unique characteristics or needs within specific subpopulations.

Feature selection bias

Feature selection bias is the selective introduction or removal of variables during model development based on pre-conceived ideas or beliefs surrounding the planned task. Extending beyond human confirmation bias, the forced inclusion of variables hypothesized to influence performance or deemed of high priority, commonly referred to as Sensitive Variables, is a common practice foundationally motivated to avoid bias. Variables, such as age, sex, and race are often deemed “sensitive” because they represent personal characteristics that predictive algorithms should ideally not discriminate against. Accordingly, their inclusion in models may be aimed at representing priority demographic groups who might behave uniquely due to a variety of differences not described by other input features. These sensitive variables therefore act as “proxy variables” (i.e. surrogates) for more complex features not adequately described by training data to enhance the accuracy and equity of healthcare AI models30,44. As an example, including birth sex in cancer prediction models may be suggested to ensure they do not predict a male sex-specific cancer (e.g., prostate cancer) in a female patient45. However, the use of proxy variables over more appropriate source data can paradoxically propagate bias. For example, a study by Obermeyer, et al., exposed racial bias in an algorithm used for predicting healthcare resource needs using a proxy variable of healthcare cost consumption. This model systematically predicted lower healthcare resource need for Black versus White patients despite similar risk levels due to lower historic healthcare spending in Black patient populations46. Expanded discussion of this is provided in Case Study 1 (Box 1). This highlights the profound impact that proxy variable choice can have on algorithmic bias, emphasizing a need for careful selection in the context of both study questions and intended model use.

Model Deployment Biases

With AI system adoption incentives in the form of workflow efficiency, an over-reliance on AI systems and a progressive de-skilling of the workforce is of genuine concern47. Several biases can be introduced following model deployment directly related to these factors. These biases are listed with examples in Table 4.

Automation bias

In the context of healthcare AI applications, automation bias reflects the inappropriate user adoption of inaccurate AI predictions due to the nature of their automated delivery. This bias can manifest in two forms: omission errors and commission errors. Omission errors occur when clinicians fail to notice or ignore errors made by AI tools, especially when the AI makes decisions based on complex details difficult for humans to detect or easily interpret. This is often exacerbated in fast-paced environments, such as radiology. Commission errors, on the other hand, arise when clinicians inappropriately place greater trust in, or follow an AI model’s judgment despite conflicting clinical evidence48.

Feedback Loop bias

Feedback Loop bias occurs when clinicians consistently adopt and accept AI recommendations, even when inaccurate, and these labels are then captured and reinforced by future training cycles. For example, the presentation of an AI labeled dataset to physicians for adjustment, rather than de-novo labeling of the raw data, can reinforce and propagate prior model biases49.

Dismissal bias

In contrast to an over-reliance on AI systems, dismissal bias, commonly referred to as “alert fatigue”, can occur when end-users begin to overlook or de-value AI-generated alerts or suggestions. This end-user introduced bias is often exacerbated by high rates of false positives that lead to a progressive distrust of a system’s capabilities. This deployment bias has been shown to lead to the dismissal of appropriate critical warnings, with potential risk of patient harm47,49.

Mitigating Bias in Healthcare AI: A Model Life-cycle Approach

Establishing standardized and repeatable approaches for mitigating bias is an expanding societal responsibility for AI-healthcare developers and providers23. This task must be recognized as both longitudinal and dynamic in nature, shifting throughout time based on evolving clinical practice, local population needs, and broader societal influence. A valuable concept for establishing frameworks for bias mitigation in AI healthcare applications is considering the ‘AI Model life cycle’, defining key stages where biases can enter, propagate, or persist10.

An AI model’s life cycle, as illustrated in Fig. 3, includes a conception, data collection and pre-processing, in-processing (algorithm development and validation), post-processing (clinical deployment), and post-deployment surveillance phase. Systematically considering bias across these sequential phases requires a multifaceted approach tailored to identify, quantify, and mitigate its impact on the core principles of fairness, equity, and equality, and maintain the ethical integrity of healthcare AI. Establishing definitions for what a meaningful bias is (e.g., one that is sufficient to mandate mitigation or usage warnings) is not a uniform task and must be independently assessed on a case-by-case basis. However, considerations should be given to setting nominal accuracy performance difference thresholds (e.g., demographic group differences) to enable the routine, automated, and iterative surveillance of AI healthcare models across relevant demographics15.

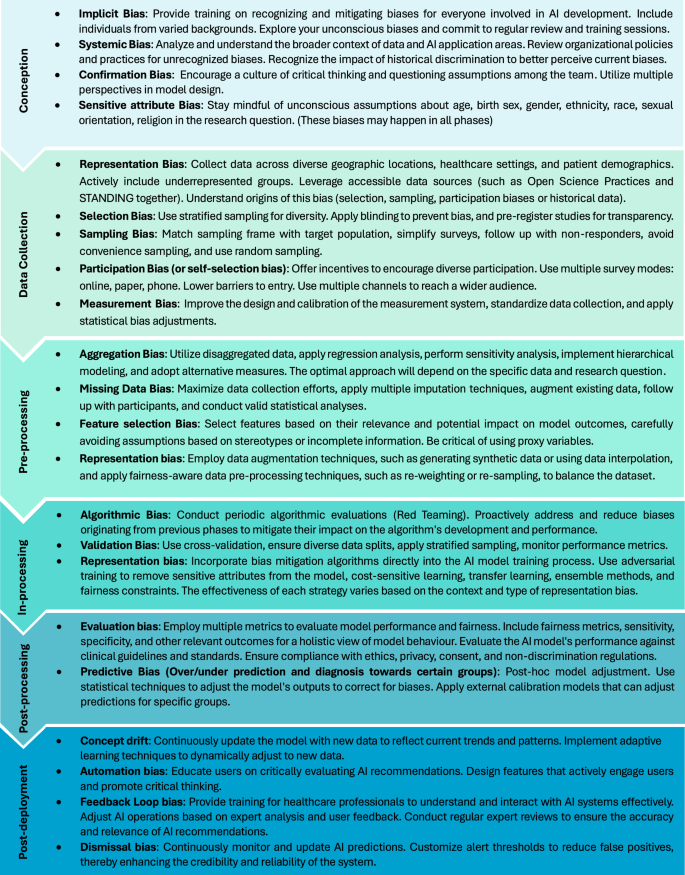

In the following sections, we provide a concise overview of each phase of the AI model lifecycle, respective recommendations for bias mitigation, and discuss the potential challenges and limitations of such strategies. Figure 4 provides an overview of detection and mitigation strategies relevant to each of these phases. Recommendations have been consolidated from various research teams and organizations, offering complementary insights into the effective implementation, management, and potential obstacles of adopting AI systems. We have also compiled a comprehensive overview of additional bias mitigation strategies, guidelines, and frameworks in AI healthcare models, which can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

This figure outlines the key strategies for addressing biases at different phases of the AI model life cycle. It highlights critical interventions from the initial conception phase through to post-deployment surveillance, ensuring that each phase in the AI development process incorporates practices aimed at promoting fairness, equity, and effectiveness. The strategies are categorized by the model’s lifecycle phases, providing a roadmap for systematic bias mitigation in AI applications.

Conception phase

As illustrated in Fig. 3, bias surveillance should begin at time of model conception, demanding a clear, clinically oriented research question from which areas of bias can then be envisioned. This, and all future phases of the model life cycle, should be systematically reviewed by a diverse and representative AI healthcare team including clinical experts, data scientists, institutional stakeholders, and members of underrepresented patient populations. During conception, teams should align with and document adherence to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) principles of the local institution while identifying plans for mitigating imbalances in team membership50 (For further details, refer to Supplementary Table 1). Meetings focussed on refining the research question, populations affected, datasets available, and intended outcomes should concurrently consider any unintended consequences for specific groups defined by race, ethnicity, gender, sex at birth, age, or other socio-demographic characteristics. In these discussions, it is critical to actively eliminate implicit, systemic, and confirmation biases ensuring research questions and AI models are designed to maximally satisfy the principles of fairness and equity across diverse socio-demographic and socio-economic groups while maintaining ethical practice51.

Bias mitigation strategies for the conception phase experience unique challenges given their need for upstream introduction. Embedding bias awareness during conceptualization requires prior education and training for all contributing members of the AI development team, which can be challenging to implement and sustain. Beyond improved awareness, critical thinking activities should be routinely engaged to overcome confirmation bias that can exist within teams, maintaining mindfulness of sensitive attribute biases such as age, gender, or ethnicity. This requires constant vigilance and willingness to question established norms. These challenges highlight a need for standardized approaches to stewarding early concepts prior to data processing, demanding a pause for consideration of systemic biases ingrained into historical policies or practice, and ensuring that target populations are fairly and equitably considered50.

Data Collection Phase

Data collection efforts should aim to generate datasets that best reflect the diversity of the population each model is intended to serve. It is essential to design data collection processes to capture an appropriate breadth of demographics, thereby allowing for the reporting and meaningful consideration of each dataset’s relevance to the target population. Special consideration should be paid to nuances in patient subgroups, such as ethnic diversity or unique characteristics, such as disabilities52. To address common biases of this phase, such as representation, sampling, selection, and measurement biases, practitioners are advised to refer to the specific mitigation strategies outlined in Fig. 4. For example, when training is dominated by historical data known to have inherent limitations or biases, a prospectively captured external validation dataset should be considered to ensure generalizability across relevant sub-cohorts53. During data collection, it is recommended to; use a variety of data sources to enhance diversity; engage accessible data initiatives such as Open Science Practices34 and STANDING together54 (For further details, refer to Supplementary Table 1); make informed decisions on the use of retrospective versus prospective data (acknowledging their respective biases and challenges); assess the accuracy and reliability of data to identify potential biases; and carefully consider inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as recruitment procedures of any clinical trial data being used. The latter commonly leads to an exclusion of specific groups of patients, limiting generalizability to real world practice23.

Achieving unbiased, broadly representative healthcare datasets remains a formidable challenge. Addressing data sparsity for underrepresented populations may not be feasible, while laudable efforts to prospectively improve data quality is time consuming. Both sampling and participation biases are notably difficult to eliminate, given that certain groups may be less inclined to participate in data collection or sharing activities, despite outreach efforts. Additionally, standardizing data collection methods to reduce measurement bias is resource intensive. While initiatives like Open Science Practices and STANDING34,54 aspire to improve the diversity of data resources available for healthcare AI, vulnerable groups may remain under-represented given a relative abundance of resources from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) populations. Finally, certain socio-demographic features, such as gender orientation, remain poorly captured by health systems and are not reliably inferred. These ongoing limitations emphasize a rapidly evolving need for targeted data collection and democratization strategies to facilitate fair and equitable healthcare AI23,52.

Pre-processing (Model Planning and Preparation) Phase

The pre-processing phase encompasses a range of tasks that are undertaken to clean and prepare raw data for model development. The mitigation of bias during this phase requires careful attention to the management of missing data, selection of relevant variables, and feature engineering to ensure appropriate data diversity, representation, and the generation of balanced sub-samples for model validation10,55. Failure to execute these techniques appropriately can introduce variance or sensitivity to data shifts, underscoring the importance of meticulous attention to prevent bias propagation33. Specifically, it is recommended to review data collection methods and demographic distributions to maximize demographic representation, assess accuracy and stability of input variables across minority groups, and consider appropriate data augmentation techniques to address sub-group imbalance. Biases such as aggregation, missing data, feature selection, and representation biases are particularly prevalent during this phase, demanding focused attention to ensure these do not compromise model integrity15,56. Details surrounding specific pre-processing bias mitigation strategies are presented in Fig. 4.

Applying these strategies must be done with appropriate understanding of their limitations and should be tailored to specific contexts as inappropriate choices or execution can inadvertently amplify rather than mitigate bias. For example, while aiming to reduce aggregation bias, shifts toward disaggregated data can lead to overly granular datasets prone to noise, leading to reduced model generalizability42. When handling missing data bias, multiple imputation may introduce inaccuracies, particularly for non-random missingness or substantial data gaps43. Data augmentation to address sparsity can generate synthetic data that fails to appropriately reflect true diversity, thus reinforcing biases42. Accordingly, nuanced understandings of bias mitigation techniques and their appropriate use is required during this phase.

In-processing (Algorithm Development & Validation) Phase

In-processing represents all activities surrounding the training and validation phase of an AI algorithm. Potential biases introduced during this phase, including algorithmic, validation, and representation bias, must be intentionally sought and addressed10. We provide an example in Case Study 2 (Box 2). This demands iterative participation from the healthcare AI team to anticipate scenarios that could seed biased model behavior50 Beyond stratified sub-group analyses, counterfactual examples should be considered to test these hypotheses during validation, purposely altering a candidate feature (e.g., ethnicity) to assess its systematic (biased) influence on model performance57 (For further details, refer to Supplementary Table 1). However, generating meaningful counterfactual examples requires a deep understanding of the dataset and relationships between features. Moreover, if not carefully implemented, counterfactual examples can lead to overfitting or produce unrealistic scenarios, thereby reducing the model’s real-world applicability. Additional limitations include difficulties in finding sufficient representative data for counterfactual examples, which could skew the results57. An alternate, albeit resource and time intensive method to identifying algorithmic bias is “Red Teaming”58. This is a process where an independent team attempts to identify biases or other vulnerabilities in an AI model, determining whether certain conditions, such as unique demographic distributions, alters performance. This may not be practical for all organizations, especially for small sized teams with limited budgets.

Under-representation of minority classes is a ubiquitously encountered challenge for healthcare datasets that should be acknowledged during model training and validation59. To address class imbalance, strategies such as resampling to balance class distributions60, synthetic data generation (such as Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE))61, and the application of cost-sensitive learning to emphasize minority class errors should be considered62. The latter is a technique where misclassifying examples from the minority class is penalized more heavily than examples from the majority class, assisting in balancing model performance. However, these strategies have limitations. SMOTE, for example, generates synthetic samples by interpolating between minority class case examples, which can result in unrealistic data points that do not accurately reflect true variability61. Random Under-Sampling, on the other hand, risks discarding potentially valuable data from the majority class, leading to information loss60. Cost-sensitive learning can lead to overfitting, especially when costs assigned to the minority classes are high62. Regardless of the techniques employed, appropriate evaluation metrics for imbalanced datasets should be used, such as F1 score and precision-recall curves. These can also serve as cost functions during training to improve model generalizability63.

Stratified cross-validation can assist in establishing representative class proportions within each fold to improve model generalizability64. This technique is reliant on the availability of large data resources and may not fully account for minority subgroups when not sufficiently represented. Fairness metrics like demographic parity, equal opportunity, equalized odds, and causal fairness (Table 5) can be leveraged to quantify and monitor for algorithmic bias. However, the application of these approaches can result in a “fairness-accuracy trade-off”, as striving for equitable treatment across different groups may result in a reduction in overall model accuracy59,60.

Federated learning techniques have gained popularity to improve model access to diverse datasets across unique healthcare environments, enabling a more collaborative and decentralized approach that ensures data privacy while reducing resource needs for model training65 (For further details, refer to Supplementary Table 1). However, while enhancing model generalizability, federated learning inherently limits team access for data pre-processing or quality assurance tasks, limiting its appropriateness for specific applications.

Adversarial training, which involves training a model to be less influenced by sensitive attributes (e.g., race, gender) by introducing adversarial examples, can be effective in reducing representation bias (For further details, refer to Supplementary Table 1). However, this technique can be computationally intensive and may lead to reduced model accuracy if adversarial examples do not accurately reflect real-world variation, again introducing a “fairness-accuracy trade-off”44.

Transfer learning is an approach that can be used to efficiently train models to perform tasks leveraging knowledge gained from historic models trained to perform similar or unique tasks. This can be used to fine-tune externally trained models using smaller quantities of local data, reducing the potential for external algorithmic bias. However, it must be recognized this may transfer unrecognized biases inherent to the original environment’s dataset, potentially perpetuating these biases into new healthcare systems53.

Model architecture choices can directly influence the transparency or interpretability of generated predictions. For example, while decision tree models provide clear feature usage insights, deep learning models offer limited insights66. However, techniques like LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations)67 and SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) can help decipher feature importance in complex models68 (For further details, refer to Supplementary Table 1). While valuable, these techniques can sometimes be inconsistent or fail to capture the true decision-making process of highly complex models, potentially leading to a false sense of interpretability66. The use of ensemble methods, where multiple models are combined to improve prediction accuracy, is one example where computational complexity is increased and interpretability reduced59. In general, model complexity should be minimized, and architectures chosen that maximize explainability, permitting the greater detectability and awareness of bias66.

Following model optimization, external validation should be used whenever feasible to assess performance across diverse environments, patient demographics, and clinical characteristics. Validation across multiple independent settings is recommended for models intended for use beyond the local institution, such as for commercial distribution. Obtaining access to diverse external datasets for validation is often challenging due to privacy concerns, data-sharing restrictions, and variability of data quality across different institutions, however, is of paramount importance when models are intended for use beyond local environments25. The size and number of unique cohorts required for external validation varies based on the model’s application and target population’s diversity, but remains central to confirming performance consistency53.

Finally, it is essential to meticulously document each algorithm’s development methodologies, ensuring clear descriptions of the target population, its accuracy, and limitations69.

Post-processing (Clinical Deployment) Phase

This phase encompasses a model’s implementation in live clinical environments70. Human-machine interface design and choice of platform deployment will influence accessibility, while planned reimbursement models can threaten equitable delivery across socio-economic groups. Adherence to Human-in-the-loop (HITL) strategies, where human experts review all model predictions, is recommended for clinical decision making71,72.

Transparent disclosure of each model’s training population demographic distributions is recommended to declare potential biases and to avoid using models in under-represented populations. The reporting of model performance for relevant sub-populations, as permitted by data resources, is also strongly recommended. Model threshold adjustments can deliver improved responsiveness to user-entered data, such as a patient’s or clinician’s preferences, recognizing individual opinions or beliefs surrounding a given prediction task73.

As stated earlier, tools to enhance model explainability for end-users are available and may improve both trust and adoption. Simple but informative ways to incorporate such insights should be considered to improve transparency and interpretability. For image-based predictions, saliency maps can be employed to highlight regions where model predictions are most strongly influenced. For traditional machine learning (ML) models, SHAP values can be used to demonstrate the relative importance and influence of data features74. It must be recognized that these tools may fall short in explaining complex model behaviors and may provide oversimplified or misleading insights that could falsely increase end-user trust.

Structured pre-deployment testing across different clinical environments and populations is recommended to identify unforeseen biases in human-machine interactions. This includes shadow deployment in live clinical environments where model results do not influence clinical behavior but are assessed for their calibration, end-user adoption, and user experience to identify barriers to fair and equitable use75,76. This process can take time and delay the model’s full implementation.

An example of implementing these strategies is seen in the DECIDE-AI guidelines (Developmental and Exploratory Clinical Investigation of DEcision support systems driven by Artificial Intelligence)77, which offer a structured approach for the early-stage clinical deployment of AI decision support systems (For further details, refer to Supplementary Table 1). By focusing on human-AI interaction, transparent reporting, and iterative validation, these guidelines aim to ensure AI models are both effective and safe in clinical practice. Such frameworks are critical to ensure the transparency and safety of AI models in clinical environments, however, are resource-intensive and time-consuming. Therefore, centralization of institutional resources and processes to support these pathways is essential.

Post-deployment Surveillance Phase

This final phase encompasses post-deployment activities for AI models in active healthcare environments, inclusive of performance surveillance, model maintenance, and re-calibration (data augmentation and re-weighting)78. Mechanisms to monitor user engagement, decision impact, and model accuracy versus standard care pathways should be adopted and purposely bridged to patient demographics to identify biased sub-group behavior or downstream inequities in clinical benefit. This is a life-long process, recognizing the potential for concept drift, feedback loop-bias, degradation in fairness metrics, or new biases emerging over time (Fig. 4). As a novel and emerging challenge for healthcare institutions, attention must be raised to administrators and practitioners that data destined for live AI models must be considered as a regulated data product, demanding ongoing quality assurance and maintenance. In this context, adhering to established guidelines and frameworks is essential to ensure sustained accuracy and equity of AI algorithms79. The FDA’s Proposed Regulatory Framework for AI/ML-based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) emphasizes a need for real-world performance monitoring, inclusive of tracking model performance to identify established or emerging bias80. While this places meaningful responsibility on AI model providers, healthcare institutions must hold responsibility to maintain an awareness of their local populations and clinical practice shifts that are commonly opaque to commercial platforms. Accordingly, programmatic approaches to AI model surveillance in clinical environments is an expanding priority for healthcare providers81.

Future Directions

Given the rapid expansion of AI healthcare innovation, there is immediate need for the meaningful incorporation of DEI principles across all phases of the AI model life cycle, inclusive of structured bias surveillance and mitigation frameworks82. This must be inclusive of actively educating and training a more diverse and representative AI developer community, implementing, and expanding institutional programs focussed on AI model assessment and surveillance, and development of AI healthcare-specific clinical practice guidelines. Adequately addressing these needs will remain a challenge due to the rapid pace of AI advancement relative to legislative, regulatory, and practice guideline development. Regardless, policy makers, clinicians, researchers, and patient advocacy groups must coordinate to enhance diversity in AI healthcare models.

Incorporating DEI principles must be perceived as an essential priority, particularly given a lack of representation in current regulatory guidelines for AI applications50,83. Moreover, there is a critical need to integrate AI and machine learning content into medical training curricula. This will prepare healthcare professionals for a future where data-driven decision-making is increasingly considered the standard of care. Understanding AI, its potential biases, and ethical implications will therefore be crucial for these individuals to appropriately contribute to its refinement and appropriate clinical use84.

Conclusion

In the evolving landscape of healthcare delivery, one increasingly influenced by AI technology, recognizing, and mitigating bias is a priority. While essential for achieving accuracy and reliability from AI innovations, addressing bias is core to upholding the ethical standards of healthcare, ensuring a future where care is delivered with fairness and equity. This ensures that AI will serve as a tool for bridging gaps in healthcare, not widening them.

Responses