Bioremoval of lead (pb) salts from synbiotic milk by lactic acid bacteria

Introduction

Food contamination by potentially harmful substances affects the health of the individuals and is a major global public health concern1. Lead (Pb) has been recognized as a toxic metal at high concentrations, and it has been linked to widespread environmental contamination and health issues across the globe when used extensively2,3. Pb exposure in trace concentration has been related to long-term nephrotoxic, neurotoxic, neurological, hematological, and cognitive issues in children, besides Alzheimer and poor concentration, anemia, nephrotoxicity, and harmful consequences on infertility, oxidative stress, and elevated blood pressure4. The primary sources of toxic elements emissions into the environment are mining and metallurgical processes, which are then transported to the food chain and end up in the food5. The International Centre for Research on Cancer (IARC) categorized the organic Pb compounds such as tetraethyl lead and tetramethyl lead in Group 3 as “not classifiable as human carcinogens”. Inorganic Pb compounds such as lead acetate, lead nitrate, lead subacetate, lead chromate, and lead phosphate, on the other hand, are classified as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” under Group 2 A6. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has issued an opinion on the potential health concerns associated with the presence of Pb in food. According to EFSA’s reports, cereals, vegetables, and tap water enormously contribute to most Europeans’ dietary exposure to Pb. They have found that present levels of Pb exposure provide a low to insignificant health risk for most individuals, although there is some worry about potential neurodevelopmental impacts in fetuses, babies, and children7. In some countries, Pb exposure dose exceeds the WHO’s weekly tolerable dose of 25 µg kg−1 of body weight8. Pb is one of the most hazardous heavy metals for human health and the environment, based on cumulative effects and carcinogenic potential, having substantial negative impacts on several tissues, organs, and systems9,10. A drinking water system may get contaminated with Pb due to environmental factors or it may develop due to problems with the distribution system, such as plumbing fixtures, solder, or service connections to residences11,12. To reduce human exposure to Pb, the WHO suggests a provisional guideline value of 10 µg L−1 for drinking water8. After all, in accordance with Commission Regulation (EC) No. 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 (as amended) setting the maximum permissible levels of certain contaminants in foodstuffs, the maximum permissible level of lead in milk should be 0.02 mg/kg13.

The determination of heavy metals in milk and select dairy products gathered from Mansoura City, Egypt, revealed the mean concentrations of Pb in raw milk, Kareish cheese, processed cheese, and milk powder ranged from 0.0 to 1.28 with Pb levels of 0.102, 0.292, 0.126, and 0.335 mg/kg wet weight, respectively14. However, greater average Pb concentrations were found in raw cow milk from the Iğdır area of Turkey (2.68 ± 0.94 mg/L)15, milk (2.98 ± 2.43) and cheese (3.08 ± 2.32 mg/kg) in Nigeria16, as well as milk (0.066 − 0.577 mg/kg) and cheese (0.240–0.733 mg/kg) examined in Romania17.

Microorganisms utilize a biological technique called bioremediation to break down contaminants. Probiotics are the finest solution to get beyond this obstacle. Currently, several approaches have been used in various kinds of food. Gram-positive probiotic bacteria, particularly Lactobacillus sp. (L.) and Bifidobacterium sp. (B.) strains seem to promise for eradicating PTEs (potentially toxic elements: cadmium, lead, zinc, copper, nickel, vanadium, and arsenic, etc.) from a wide range of foods18,19.

As of March 2020, there are 261 species in the genus Lactobacillus, and they exhibit remarkable diversity in terms of phenotypic, ecological, and genotypic features. Researchers propose to reclassify the genus Lactobacillus into 25 genera, including the emended genus Lactobacillus, which includes host-adapted organisms that have been referred to as the L. delbrueckii group, Paralactobacillus, and 23 novel genera. This classification is based on a polyphasic approach that includes core genome phylogeny, (conserved) pairwise average amino acid identity, clade-specific signature genes, physiological criteria, and the ecology of the organisms. Furthermore, because of recent taxonomic modifications, the L. casei group was reclassified as a new genus called Lacticaseibacillus20.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) play a crucial role in food processing by producing a wide range of fermented products of plant and animal origin due to their capacity to ferment the rich diversity of carbohydrates found in food raw materials21. Furthermore, several scientific sources have verified the functional properties and biotechnological potential of the exopolysaccharide generated by Lactobacillus strains22,23.

They have a variety of beneficial effects on human health, including the biodecontamination of various kinds of pollutants as they adhered to and are colonized in the digestive system24. The newly discovered L. reuteri strains Cd70-13 and Pb71-1 were shown to have outstanding probiotic, metal sorption, and adhesive qualities in a research. This suggests that they have the capacity to thrive in the intestinal milieu and absorb the tested metals from the environment25. At least 106 to 107 CFU mL−1 of live bacteria should be present in the food to positively impact people’s health26,27.

Prebiotics, which are non-digestible oligosaccharides added to meals containing probiotic bacteria like inulin, may enhance the health of the host by changing the makeup or activity of the intestinal microbiota28. A new definition of prebiotics has been released by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP): ‘a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit’29. Prebiotics’ effects on health are still developing, but they currently include advantages for the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., immune stimulation, pathogen inhibition), cardiometabolism (e.g., blood lipid levels lowered, effects on insulin resistance), mental health (e.g., metabolites that affect brain function, energy, and cognition), and bone (e.g., mineral bioavailability), among other areas30. Prebiotics can be applied directly to other microbially colonized body areas, such as the skin and vaginal canal, even though the majority of them are now taken orally29.

Probiotics and prebiotics together are referred to as synbiotics. “A mixture comprising live microorganisms and substrate(s) selectively utilized by host microorganisms that confers a health benefit on the host” is the revised definition of a synbiotic provided by the ISAPP31. Probiotics such as Lacbobacilli and Bifidobacteria strains are frequently utilized in symbiotic preparations, whilst oligosaccharides such as fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and galactooligosaccharides (GOS), xyloseoligosaccharide (XOS), and inulin are the most prevalent prebiotics32.

The effects of probiotics on toxic metal salts and their detoxifying activities have not been the subject of many investigations. The principal objective of this research was to investigate the ability of five native probiotic bacterial species to bioremediate and remove Pb in situ using the prebiotic inulin (types of milk based on fat content; low-fat, semi-fat, and high-fat milk). Water-soluble Pb compounds like lead acetate and lead nitrate are often used as intermediate materials in a variety of processes, including those involving paint chips that include lead, insecticides, food preparation containers, machinery used in the food industry, pipes and fittings in factories, etc33. They can be readily absorbed by humans via their skin, respiratory system, meals, and water34,35. Another goal of the current study was to look at how prebiotics (inulin), affect the activity and capacity for decontamination of probiotic bacteria. The impacts of several forms of heavy metal salts (including two main Pb forms, namely nitrate and acetate salts) on the behaviors of probiotic bacteria during biodetoxification processes were investigated for the first time.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Lead nitrate [Pb(NO3)2] and lead acetate [Pb(C2H3O2)2], supplied by (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Nitric acid (HNO3) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), among other acid digestion reagents, were all of the analytical grade (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). We utilized double distilled water to make solutions and dilutions (GFL, Burgwedel, Germany). In the inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES; Spectro, Arcos model SPECTRO, Kleve, Germany), the plasma gas included argon and N2 gas (99.999%). All three varieties of milk for probiotic inoculation were UHT Tetra Pak and supplied from Iran Dairy Industries (Pegah Co., Tehran, Iran). Following the Iran National Standards Organization (INSO), the used types of milk had the following chemical characteristics: low-fat UHT milk (at least 0.5 to 1.8% w/w), semi-fat UHT milk (between 1.8% and 3%w/w), and high-fat UHT milk (at least 3% w/w)36.

Probiotic strains and prebiotic

In this investigation, Lactobacillus paracasei IRBC-M 10,784, obtained from Tarkhineh, a traditional fermented dish, Bifidobacterium bifidum BIA-7, Lactobacillus rhamnosus IBRC-M 10,782, Bifidobacterium lactis BIA-6, and Lactobacillus acidophilus PTCC-1932, originated from traditional dairy products, were employed as five native probiotic bacterial strains from Iran. The probiotics applications were made based on the guide’s directions, with all bacteria purchased from (Takgene Zist Co., Tehran, Iran). Iran’s Biological Resources Center (IBRC) has served as the point of reference for demonstrating and validating the probiotic impact of these novel strains registered by the company. A portion of 0.1 g of freeze-dried culture medium with > 109 CFU g−1 cells was applied as the probiotic medium. Varied fat contents of milk were investigated for the Pb-binding test. Further, Frutafit® TEX! inulin (Sensus, Roosendaal, the Netherlands) from chicory root, mainly composed of long-chain saccharides with 23 monomers, was administered as a prebiotic agent to encourage bacterial activity, thereby enhancing the probiotic bacteria’s functional qualities in milk.

Biosorption experiments and analytical instruments

The test tubes containing 10 mL of UHT milk, without and with inulin (5% w/w), and 0.1 g of the freeze-dried culture medium with ˃109 CFU of each bacterial strain (based on the results of microbial culture experiments: 5 × 109 (L. acidophilus), 7 × 109 (B. lactis), 2.5 × 109 (B. bifidum), 1.5 × 109 (L. rhamnosus) and 7 × 109 (L. paracasei) CFU per 0.1 g bacterial source) were used to determine the capacity of five indigenous probiotic strains to bind Pb salts. In order to re-sterilize the UHT milk and eliminate any initial microbial contamination before adding probiotics, the UHT milk samples were heated at 90 °C for 15 min and then cooled to 37 °C, the optimal temperature for the proliferation of probiotic bacteria37. After inoculation (˃109 CFU mL−1), the lead salt (50 mg L−1) was introduced into the UHT milk, and the mixture was then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with 10% CO2. The Pb removal rate was measured at different incubation durations (0, 60, and 120 min). The pH changes were also measured by a pH meter (913 pH Meter, Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland) to assess the probiotic bacteria’s activity. Afterward, 3 mL of the solution was transferred to another tube and centrifuged (37 °C, 9000 g, 10 min). Aliquot of 1 mL of the supernatant was extracted, digested, and examined to determine the unbound Pb concentration38,39. For digestion, 10 mL of 65% nitric acid was mixed with 1 mL of the supernatant solution. To eventually produce a clear, turbidity-free solution that could be injected into the analysis instrument, the solution was heated to 150 °C for 4 h after being held at 90 °C for 45 min in a hot water bath40. All samples were assessed by the ICP-OES instrument (Spectro, Arcos model SPECTRO, Kleve, Germany) to determine the amount of Pb.

FTIR-ATR analysis

The functionally groups and the potential interlinkage between the probiotics and metals in the milk samples were investigated using an FTIR-ATR spectrophotometer (Agilent Cary 630 FTIR, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All treatments’ area spectra were captured between 4000 and 500 cm−1. The mean transmittance and vibration frequencies of bacteria and metal functional groups probably linked to the bioremediation process were investigated.

Statistical analysis

All the analyses were done in triplicate and the results were presented as the mean ± SD (standard deviation). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the post-hoc Tukey HSD test, were performed using SPSS software version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA), to demonstrate the statistical significance of data comparisons. Statistics were deemed to be significant at p < 0.05. Additionally, Matlab software R2013a (Math Works, Natick, USA) generated an exploratory analysis model utilizing Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The FTIR spectra interpretation was conducted using Origin software 2019b (Originlab, Massachusetts, USA). The similarity or distance between the clusters (as dendrograms) and their evolution in each group were analyzed by Minitab software version 19 (Minitab, Pennsylvania, USA).

Results and discussion

The pH variation of ambient

The rate of development of probiotic bacteria was shown to be connected to decreases in the pH of the culture medium41. Table 1 presents the impact of the probiotic bacterial strains on the pH of the milk (low-fat, semi-fat, and high-fat) at different incubation intervals when the media are combined with inulin and lead salts. The best pH-decreasing settings were observed under the ideal growth conditions, showing that pH reduction is greatly related to the viability of the probiotic bacteria. Significant pH level variations across incubation durations were seen in all probiotics (p < 0.05). Without the addition of Pb and inulin, the initial pH values of the low-, semi-, and full-fat milks were 6.61 ± 0.039, 6.43 ± 0.038, and 6.34 ± 0.076, respectively. The findings demonstrate that the addition of Pb salts led to pH shifts toward the acidic side, particularly in the case of nitrate salts. Additionally in low-fat milk, the addition of inulin caused higher acidity alterations. According to the findings, in low-fat milk, the samples including L. paracasei + inulin + lead acetate had the lowest pH values (5.94 ± 0.030) while the media containing B. lactis + lead nitrate had the highest values (6.66 ± 0.010) throughout the incubation period. The samples containing B. bifidum + lead nitrate had the greatest pH value (6.49 ± 0.015) in semi-fat milk, whereas the others including L. paracasei + inulin + lead nitrate had the lowest pH value (5.90 ± 0.010). Additionally, in the medium of high-fat milk, the samples comprising L. paracasei + inulin + lead nitrate had the lowest pH values (5.74 ± 0.035) while the media containing B. bifidum + lead acetate + inulin had the highest pH values (6.46 ± 0.015). According to the findings of pH alterations, L. acidophilus PTCC-1932 was found to have the lowest average pH reduction while L. paracasei IRBC-M 10,784 solutions had the greatest average pH decrease.

The findings showed that adding inulin mainly might speed up pH declines without having significant effect. The samples containing inulin and lead nitrate had the lowest pH levels at the end of the incubation period in each probiotic solution. In conclusion, samples containing lead nitrate had pH decreases that were more pronounced than ones containing lead acetate. This was connected to lead nitrate having a firmer acidity as seen by its lower acid dissociation constant (pKa) value as compared to lead acetate. Halttunen et al. (2008), evaluated how different probiotic strains affected Pb and Cd elimination at various pH ranges (2–7)42. They revealed that Pb and Cd elimination increased as pH rises. Moreover, they claimed that the pH may have an impact on the conflict between protons and heavy metal cations that compete for negative cell wall receptors. Their findings demonstrated that the elimination of Pb and Cd is increased when the pH is higher than 3. They maintained that the deprotonation of carboxyl groups may be the reason for the rise in binding effectiveness brought on by an increase in pH. Toxic metal cations and protons may compete with one another for negative receptors as a result of pH’s action. According to Farrokh et al. (2019), utilizing inulin (3%) of may boost the probiotic’s survivability, particularly L. acidophilus, resulting in pH reduction43. Similarly, Oliveira et al. (2009), revealed that inulin increased the acidification rate in the fermented skim milk containing probiotic bacteria and accelerated the time required for the product to get the final pH of 5 44. On the contrary, Rezaei et al. (2014) indicated that adding inulin at a concentration of 2% resulted in a considerable increase in pH level45. However, Mazloumi et al. (2011) reported that inulin does not substantially alter the pH of the surrounding environment46.

Analytical method validation

The calibration curve was plotted using various concentrations of standard lead solution (1 to 50 mg L−1). The regression equation yielded the value y = 30381x + 2352.7. ICP-OES demonstrated excellent linearity (R2 > 0.9999). The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ), calculated as 3 and 10 folded of the standard deviation of the analytical responses divided by the calibration curve’s slope (3 SD/b and 10 SD/b), were 0.17 and 0.57 mg L−1, respectively. The ICP-OES obtained recovery values of > 99%.

Probiotics’ effects on pb salts mitigation

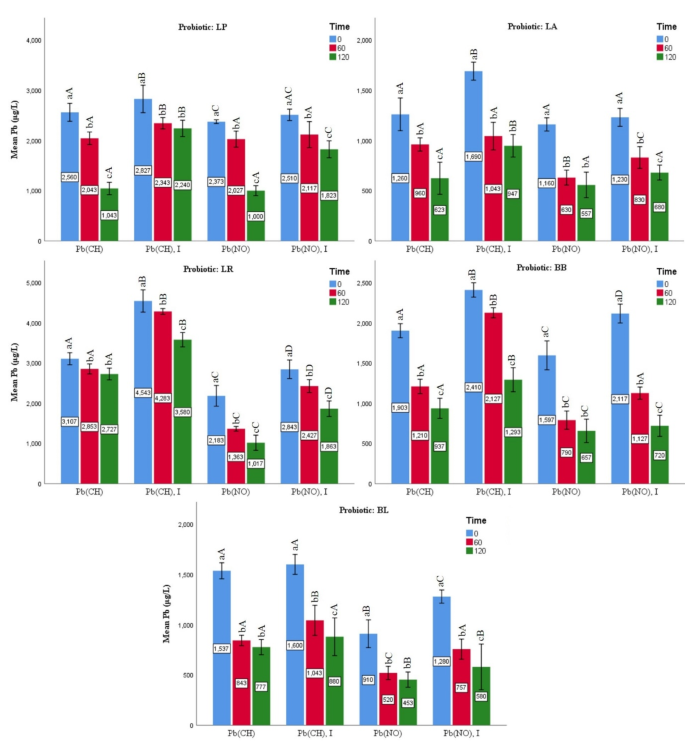

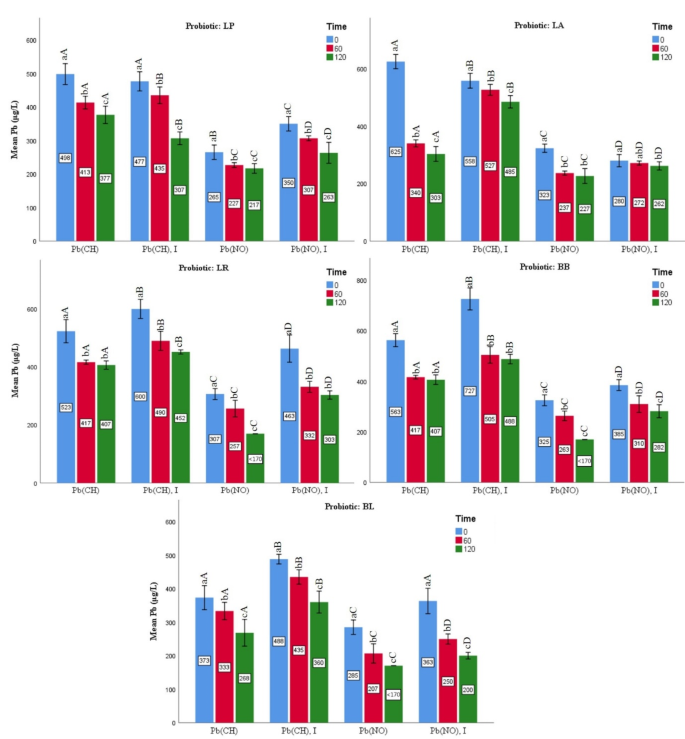

According to results of the probiotic strains’ impact on the Pb metals removal in low-fat milk, B. lactis (94.41%), L. acidophilus (94.19%), B. bifidum (91.55%), L. paracasei (87.54%), and L. rhamnosus (83.60%) had the highest to lowest percentages of Pb salts removal (Fig. 1). At the end of the incubation period, the ratio of Pb salt removal was significantly higher than that of the initial samples (p < 0.05). The samples containing lead nitrate without inulin (453 µg L−1) had the highest Pb removal among the groups treated with B. lactis after 120 min of incubation. The bacterial groups that contained lead nitrate had the maximum removal rates. Furthur, the samples containing inulin had lower Pb salt removal rates than the groups without inulin.

Effects of the probiotic bacteria on lead levels under various incubation times in LOW-FAT MILK. Values are mean ± SD of three experiments. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) of the strains are indicated with different letters above the graphical bars. Separately for each bacterium, different small letters represent significant difference at the time of experiment. Different capital letters represent statistical difference between four treatment groups [lead nitrate/Pb(NO); lead nitrate and inulin/Pb(No), I; lead acetate/Pb(CH); and lead acetate and inulin/Pb(CH), I].

As shown in Fig. 2, the results of semi-fat milk revealed that the average percentage of Pb removal was associated with samples containing B. lactis (98.13%), L. paracasei (97.93%), L. acidophilus (97.78%), L. rhamnosus (97.63%), and B. bifidum (97.57%). At the end of incubation time (120 min), the removal rate of Pb salts decreased significantly (p < 0.05). Moreover, the sample containing lead nitrate without inulin had the greatest percentage of Pb removal among the B. lactis-treated groups, at about 99.66% (170 µg L−1). Native probiotic bacteria showed a greater capacity to eliminate lead nitrate than those containing lead acetate in all treatments. Additionally, a substantial increase (p < 0.05) in the rate of elimination of Pb salts, particularly lead nitrate, was seen in the inulin-containing groups compared to the groups without inulin.

Effects of the probiotic bacteria on lead levels under various incubation times in SEMI-FAT MILK. Values are mean ± SD of three experiments. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) of the strains are indicated with different letters above the graphical bars. Separately for each bacterium, different small letters represent significant difference at the time of experiment. Different capital letters represent statistical difference between four treatment groups [lead nitrate/Pb(NO); lead nitrate and inulin/Pb(No), I; lead acetate/Pb(CH); and lead acetate and inulin/Pb(CH), I].

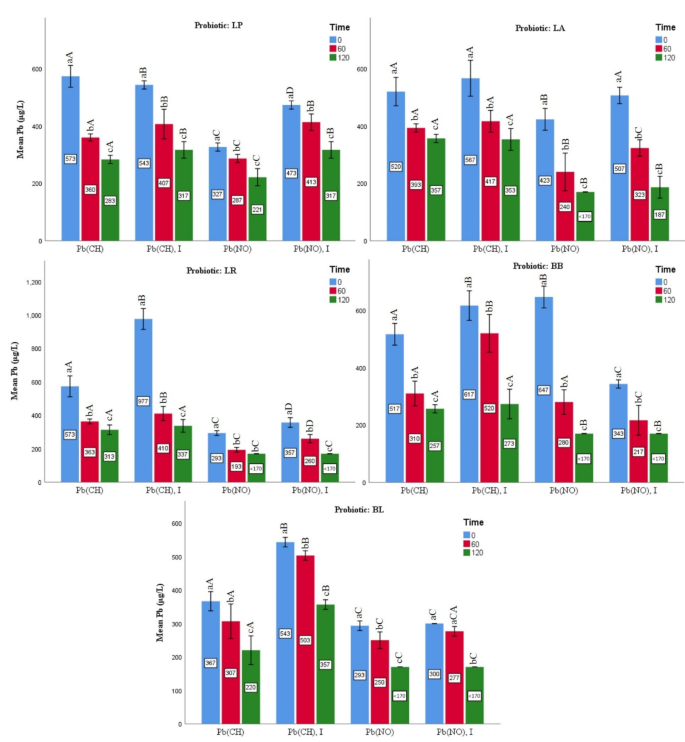

According to the results shown in Fig. 3, in the environment of high-fat milk, the samples containing B. lactis (98.12%), B. bifidum (97.83%), L. rhamnosus (97.79%), L. acidophilus (97.77%), and L. paracasei (97.73%) had the average percentage of Pb salts removed from the highest to the lowest value. The amount of Pb significantly decreased from the start of exposure to the conclusion of the incubation period. Samples containing B. lactis + lead nitrate, with or without inulin, showed the greatest biological removal of Pb salts (170 µg L−1; 99.66%) after 120 min in all groups. Except for the group containing B. bifidum, the groups containing inulin had a larger amount of Pb removal than the groups without inulin in the bacterial treatments exposed to lead nitrate. Probiotics removed lead nitrate more effectively than those that had lead acetate.

Effects of the probiotic bacteria on lead levels under various incubation times HIGH-FAT MILK. Values are mean ± SD of three experiments. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) of the strains are indicated with different letters above the graphical bars. Separately for each bacterium, different small letters represent significant difference at the time of experiment. Different capital letters represent statistical difference between four treatment groups [lead nitrate/Pb(NO); lead nitrate and inulin/Pb(No), I; lead acetate/Pb(CH); and lead acetate and inulin/Pb(CH), I].

A summary of the findings regarding the overall percentage of Pb metal absorption and removal from milk media containing Pb salts and inulin revealed that milk with varying fat contents—low-fat, semi-fat, and high-fat—are related to the percentage of Pb removal that ranges from the lowest to the highest. Numerous investigations have confirmed that inulin prebiotics can boost detoxifying and antimicrobial activity, boost probiotic bacteria’s logarithmic development, and increase probiotic resilience to unfavorable environmental conditions24,47,48. By forming a stable complex and protecting biological targets from metal ions, these polysaccharide compounds efficiently bond with toxic heavy metals, reducing their negative effects and leading them to be expelled from the body49. This explains why probiotics’ capacity to eliminate Pb salts from the environment is enhanced by inulin. The findings of several studies showed that heavy metals may bond with milk constituents, particularly proteins and lipoproteins of the milk fat globule membrane50,51. Therefore, it can be concluded that when toxic elements are introduced to the environment of milk containing probiotic bacteria, some of the metals may be linked to the primary components of milk and out of the probiotics’ reach in addition to binding to the probiotics’ cell wall sites during the process of bioabsorbtion and bioaccumulation. Therefore, when measuring the quantity of free heavy metals in the supernatant solution by centrifuging the milk, the metals bound to proteins and lipids may be precipitated together with the dry matter of the whole milk, resulting in a decrease in the amount of free heavy metals in the environment. A few minutes after heavy metal addition to the bacterial solution, probiotic bacteria like Lactobacillus sp. and Bifidobacterium sp. can bind to metal ions52,53.

Probiotic bacteria’s byproducts such as organic acids’ ability to dissolve metals, exopolysaccharides (EPS), siderophore-mediated bioassimilation, and efflux pump-mediated bioleaching are also crucial in the elimination of PTEs. Probiotic bacteria’s two primary methods for removing PTEs are biosorption and bioaccumulation, however there are other pathways including ion exchange, complexation, precipitation, reduction, chelation, solubilization, biotransformation, and bioleaching24. The synthesis of EPS by bacteria serves as a barrier to shield them from harmful environments such temperature fluctuations, nutritional stress, and the presence of hazardous chemicals54. By preventing metal ingress and serving as a precursor for metal ion binding, EPS synthesis is essential for cell defense55. The bacteria create significant amounts of exopolymeric molecules, with protein and EPS often predominating, in order to live under situations of metal stress56. Moreover, the structure of the EPS includes a large number of anionic functional groups that can interact with metal ions, including carboxyl, hydroxyl, sulfate, phosphate, and amine groups57. Because of its binding capacity, the EPS has been recommended as a potentially effective adsorbent for metal pollutants. EPS synthesis by Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains isolated from food and human gut microbiota has been demonstrated by researchers58,59. According to Oleksy-Sobczak et al. (2020), the production of EPS by L. rhamnosus begins at the initial stage of the growth period. However, the cultures that were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and for 30 h at 25 °C showed the highest efficiency of EPS synthesis by the L. rhamnosus strain ŁOCK 0943 60.

According to some studies, exopolysaccharide-producing Gram-positive probiotic bacteria like L. rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium sp. attach toxically cationic metals to their anionic surface groups61,62. Bifidobacteria’s phospholipid composition differs from lactobacillus’, particularly in terms of polyglycerol phospholipid and aminoacyl-phosphatidylglycerol, which may be evidence of the capacity of various probiotics to bind to and eliminate heavy metal toxins from the environment63. The combination of specific proteins and fat as the major components of milk is necessary for probiotic bacteria cell survival under unfavorable environmental circumstances such as toxicity, excessive acidity, and the presence of bile salts. In settings simulating the human digestive system, the research by Conway et al. (1987) demonstrated the direct impact of milk protein on the survival of probiotic bacteria64. In another study, Koziol et al. (2011) found that adding 2% casein macropeptide to milk significantly boosted the population of B. lactis, suggesting that this substance may function as a prebiotic in adverse conditions65. Furthermore, Ziarno et al. (2015) observed that adding proteins such as skimmed milk powder, whey protein, and 2.2% or more fat to milk had a favorable impact on the survival of B. bifidum. In the case of B. lactis, there was also a substantial difference in survival when the quantity of fat in milk was approximately 4.0% or higher66. As a result, the presence of protein and fat in milk, as well as the presence of inulin in the environment, can have protective effects by increasing the viability and tolerance of B. lactis to the toxic effects of Pb salts, and these bacteria can then have a high potential in detoxification. Another aspect that contributes to the tremendous ability of Bifidobacterium sp. (such B. lactis and B. breve) to remove heavy metals and other dangerous environmental contaminants from the environment is the presence of the K gene in their cells67,68. The K gene in this bacterium’s DNA (dnaK) improves the bacteria’s ability to protect from adverse biological circumstances, including toxins, heat shock, and osmotic stress. In severe environmental conditions, such as toxic metals exposure, this gene expresses significantly and rapidly. It has been discovered that bile salts increase the expression of this gene in Bifidobacteria sp., particularly B. lactis69.

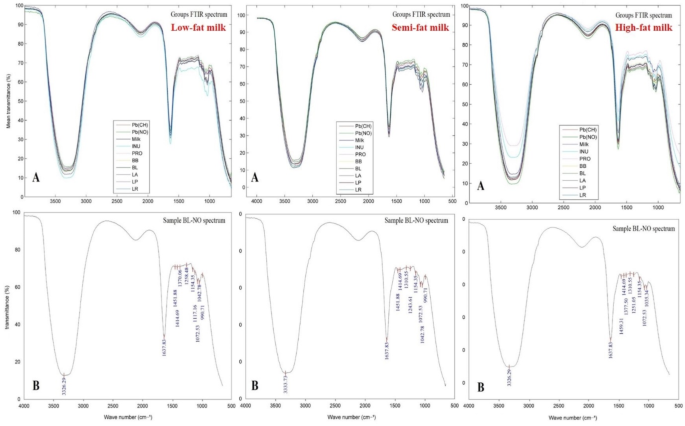

FTIR-ATR results

To recognize the distinctive chemical functionally groups responsible for the Pb ions’ biosorption, FTIR-ATR spectroscopy was conducted. Overall, 29 spectra representing inulin (INU), nitrate salt as Pb(NO), acetate salt as Pb(CH), and milk as media were obtained for milk varieties (Fig. 4). Each probiotic was evaluated in five phases: inulin, inulin-free, Pb, Pb-free, and probiotic alone (PRO). The mean transmittance for each group of B. lactis treatment was shown in Part A. The FTIR spectra of BL-NO (B. lactis + lead nitrate), the treatments with the highest rate of Pb removal from all milk media, were also shown in Part B to identify the functional groups.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectra of the types of milk samples. Part A: Pb(CH) as lead acetate, Pb(NO) as lead nitrate, INU as inulin, Milk as media, PRO as bacteria only, and mean transmittance of each probiotic (LP: L. paracasei; LA: L. acidophilus; LR: L. rhamnosus; BB: B. bifidum; BL: B. lactis) sample with/without inulin and lead salts; Part B: B. lactis and lead nitrate (BL-NO).

The fingerprint area showed the greatest rate of transmittance variations, according to the FTIR plots (900–1400 cm−1). C-O (carbonyl groups) and COO- anions (carboxylate groups) were associated with the 1414–1362 cm−1 range. Vibrations at the range of 1280–1198 cm−1 owing to C-O or -OH (hydroxyl) stretching vibrations, C = O deformation vibration, and phosphate groups (P = O) belonging to nucleic acids, revealed that the probiotic bacteria might conduct crucial functions in Pb bioremediation. Absorption bands at the wavenumber range of 1109 –990 cm−1 were functional groups that interacted with probiotics’ cell wall glycopeptides, lipopolysaccharides, and polysaccharides, via -OH stretching, C-O groups, organic P = O groups, and C-O-C stretching ether bonds70. Each band’s wavenumber variations were marginally distinct in microorganisms. These results demonstrated the participation of hydroxyl (OH), carbonyl (C = O), carboxylic (–COOH), phosphate (P = O), amine (–NH2), and amide (–C(= O) = N) functional groups in lead salt bioremediation processes mediated by electrostatic attraction on the bacteria membranes. Scientists concluded that OH, –COOH, C = O, and –NH2 groups were the primary functional groups responsible for toxic elements biosorption71,72,73. Lactic acid bacteria had specific peaks at 1110 cm−1 wavelength while Bifidobacteria sp. had peaks at 1155 cm−1 wavelength. The following components contribute to the vibration of the functional group in the milk: (1) Water peaks: -OH stretching vibrations in 3223 cm[–1; (2) Fatty acid peaks: -CH2 (methylene) asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations in 2924 cm[–1 and 2852 cm[–1, respectively, C = O (carbonyl) groups from the triacylglycerol ester bonds in 1746 cm[–1, and CH2 and CH3 bending vibrations in 1466 cm[–1; (3) Protein peaks: C = O stretching vibrations, and N-H bending vibrations in 1638 cm[–1; (4) Carbohydrate peaks: C = O stretching vibrations in 1075 cm[–1 and (5) Fingerprint region peaks: CH2 wagging and rocking bending vibrations in 1025 cm–1 74.

Chemometric analysis

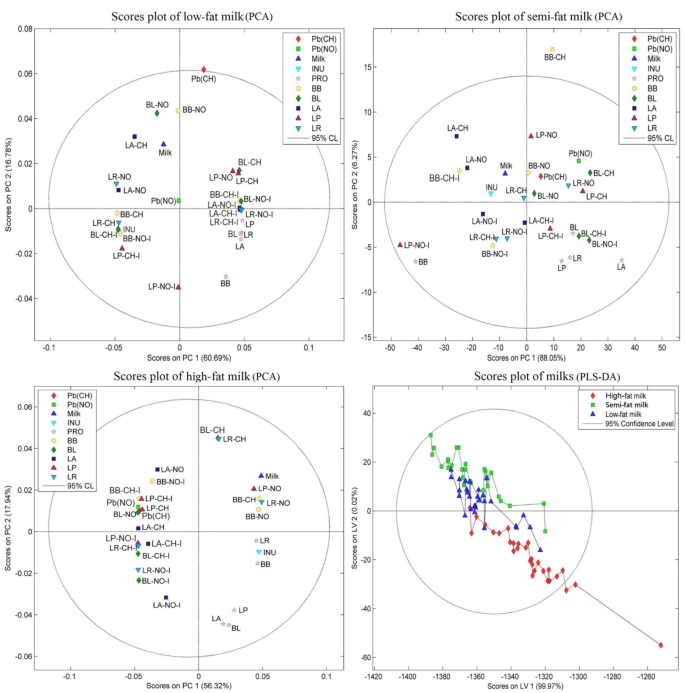

Due to the limited contact period (2 h), there were only slight FTIR modifications; however, the wavenumber transitions were compatible with the metal binding mechanism to the bacterial surface. Consequently, it seems complicated to extract information about the bacterial binding capacity to lead salts from data analysis utilizing restricted wavelength regions or single peaks. Additionally, it was challenging to separate samples by functional categories and interactions. These results were expounded using spectral ranges between 4000 and 500 cm−1 and chemometric techniques. The PCA data analysis was utilized as a multivariate tool to evaluate various classification algorithms and to highlight commonalities between the treatment samples. Figure 5’s PCA modeling, which was carried out for each type of milk media, demonstrates the excellent dependability of the models with total cumulative variance coverage percentages of around 93.37% (for the low-fat milk), 97.77% (for the semi-fat milk), and 93.41% (for the high-fat milk). PCA analysis revealed that the spectrum pattern of the samples containing just probiotic bacteria was fully distinct from the other control and treated samples in the low-fat and high-fat milk models, whereas this difference was relatively obvious in the semi-fat milk model. Additionally, the categorization of samples treated with probiotics, Pb salts, and inulin according to their spectrum patterns in all three milk models showed that samples treated with inulin were classified separately from those treated with Pb salts without inulin. However, neither the kind of Pb salts nor the type of bacterial treatments could be specifically categorized. It should be noted that the short exposure period in the treatment solutions and the intricate matrix of the milk metrics may be responsible for the lack of precise categorization of the spectrum pattern between various treatments. In addition, the PLS-DA analysis used to classify milk types demonstrates the model’s excellent dependability (total cumulative variance of nearly 99.99%), as well as the full separation of the aforementioned models in terms of the spectrum pattern in milk with various fat percentages.

PCA and PLS-DA analysis score plot of the treated milk samples. Pb(CH) as lead acetate, Pb(NO) as lead nitrate, INU as inulin, Milk as media, PRO as bacteria only, and mean transmittance of each probiotic (LP: L. paracasei; LA: L. acidophilus; LR: L. rhamnosus; BB: B. bifidum; BL: B. lactis) sample with/without inulin and lead salts.

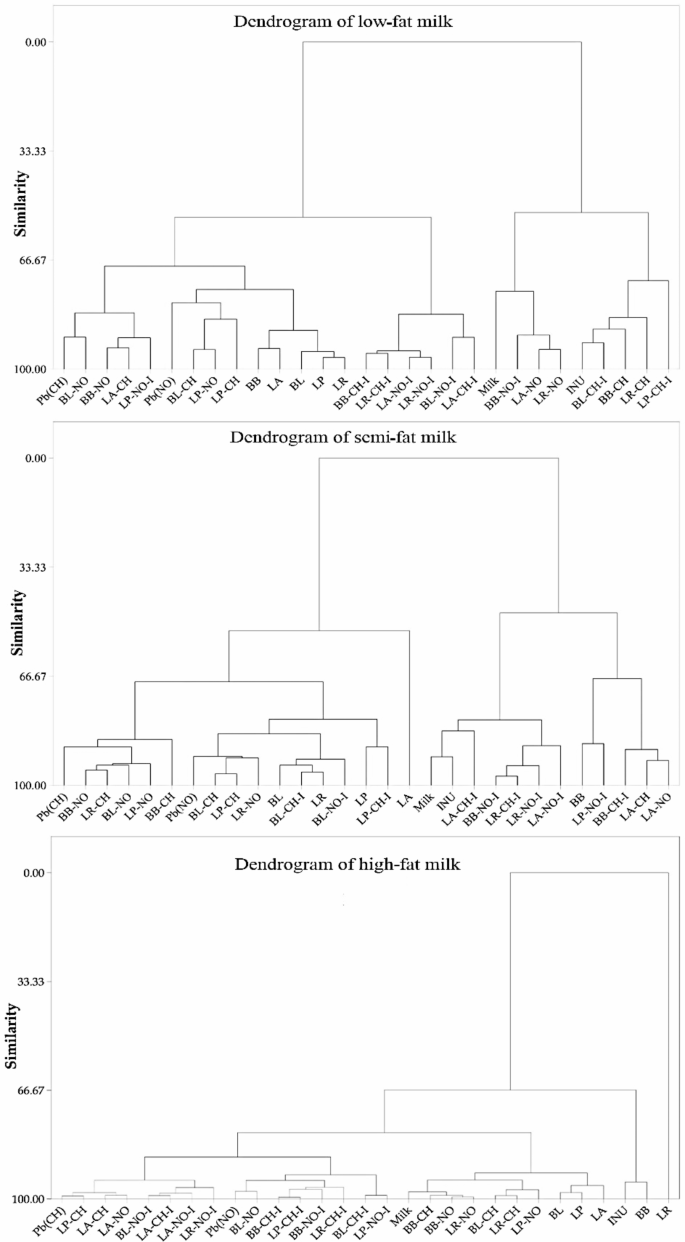

The results of a hierarchical cluster analysis of low-fat, semi-fat, and high-fat milk models (Fig. 6) revealed that low-fat and high-fat milk models, as well as samples containing only probiotics, have a high degree of similarity in terms of the organic compound type, chemical bonds, functional groups, and molecular structure. However, this shortcoming was more significant in the semi-fat milk model in relation to the inulin-containing treatment samples. The short exposure time of the solutions under treatment, the complexity of the matrix of the milk metrics, which makes the environment more stable in regards to the stability of various bands, as well as the low amount of Pb salts and other compounds used in the treated solutions, are the main causes for the lack of a separate classification of spectra patterns.

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of the treated milk samples. Pb(CH) as lead acetate, Pb(NO) as lead nitrate, INU as inulin, Milk as media, PRO as bacteria only, and mean transmittance of each probiotic (LP: L. paracasei; LA: L. acidophilus; LR: L. rhamnosus; BB: B. bifidum; BL: B. lactis) sample with/without inulin and lead salts.

Conclusions

The present findings indicated that dietary toxins could efficiently be removed by simultaneously utilizing inulin prebiotics and indigenous probiotics. B. lactis BIA-6 had the greatest capacity among native probiotic bacteria to eliminate Pb salts from milk medium. According to the results, the probiotics’ detoxification activity regarding the Pb salt type was considerable; thereby, lead nitrate was further removed. Adding inulin was generally able to accelerate the pH reduction activity in the environment of the assessed milk types, while the effects were not very noteworthy. The medium without inulin had a greater Pb salt removal rate in the low-fat milk groups. Nonetheless, there was no discernible difference in the outcomes compared to the inulin content groups. The groups containing inulin demonstrated a higher level of Pb removal than the groups without inulin in the majority of the samples treated in semi-fat and high-fat milk mediums. Based on the present findings, it can be suggested to use diverse probiotics and evaluate probiotics’ proliferation and growth rate, viability, and decontamination ability when exposed to various heavy metal salts or different environments.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by Iran national committee for Ethics in biomedical research (IR.SBMU.NNFTRI.REC.1398.007). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Responses