Black raspberry supplementation on overweight and Helicobacter pylori infected mild dementia patients a pilot study

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative condition associated with dementia, memory and cognition impairment, and behavioral changes. AD is estimated to affect over 40 million people globally, with the prevalence of the condition anticipated to increase over the next several decades, especially in low socioeconomic status countries1,2. The pathophysiology of AD is not clearly understood, but genetic and environmental risk factors appear to contribute to the condition.

One condition potentially related to AD development is infection with the bacterium Helicobacter pylori. AD affects nearly 4.5 billion people worldwide. This condition disproportionately affects those from disadvantaged, low socioeconomic status, or immigrant backgrounds. Lack of adequate sanitation and nutrition are environmental risk factors for developing infection3,4,5. H. pylori infection frequently presents as general dyspepsia. Still, it has the potential to lead to more severe conditions such as peptic ulcer disease, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma, which makes it imperative to diagnose and treat H. pylori infection, given its significant global prevalence6. H. pylori has been implicated in AD via the gut-brain axis (GBA), a network connecting the gastrointestinal and central nervous systems via signals such as metabolites from gut microbiota, gastrointestinal hormones, and immunologic modulators7. As bacteria such as H. pylori infect the gastrointestinal tract, they may affect immune and metabolic signaling within the GBA and thereby lead to CNS changes. Recent studies indicate a possible link between AD and H. pylori infection, evidenced by factors such as increased anti-H. pylori IgG in AD patients8,9. However, the research on H. pylori in concurrence with AD remains inconclusive.

Another gastrointestinal factor implicated in AD development is obesity. As with H. pylori infection, obesity may be related to AD via the gut-brain axis, especially when considering immunological factors. For instance, obesity is associated with increased susceptibility to bacterial infection, reduction in gut microbiome diversity, and subsequent pro-inflammatory profiles, a cascade that may increase the risk of developing AD10. Interestingly, several studies demonstrate that this risk appears to be highest when obesity is present in middle age; the reason for this remains unclear11,12.

Together, H. pylori infection, obesity, and AD form a triad of epidemiologically overall conditions that may be linked via immunological and metabolic pathways of the GBA. However, the literature remains inconclusive regarding definitive relationships, and no previous studies have attempted to connect all three of these conditions. This merits exploration regarding treatments that can target these pathways, providing more favorable inflammatory profiles and hopefully reducing AD incidence. One potential treatment route may be a dietary modification, which has been demonstrated to affect both obesity and H. pylori infection by modulating the gut microbiome and inflammatory cascades13,14. Our previous research has highlighted the role of black raspberries (BRBs) in autoimmune and malignant conditions and found that in certain situations, BRBs and their metabolic components suppress pro-inflammatory markers and foster gut microbiota with less inflammatory profiles. For instance, in a murine model of ulcerative colitis, diet supplementation with BRBs was associated with reduced levels of phospho-IκBα, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), toll-like receptor and prostaglandin E2, all of which are associated with inflammation15,16,17,18,19. It is possible that the gastrointestinal effects demonstrated to result from BRBs may extend to conditions such as obesity and H. pylori, both of which are also strongly associated with inflammation.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether supplementation of diet with BRBs has a meaningful effect on the gastrointestinal conditions of H. pylori infection and overweight and the development of AD in a clinical trial setting.

Methods

Clinical trial

The clinical trial protocol was approved by the IRB at Chung Shan Medical University, Taiwan (protocol number CS2-21103, Title: The improvement of black raspberry in obese and mild AZ patients infected with H. pylori) and registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (ID: NCT05680532; Title: The Improvement of Black Raspberry in Obese and Mild AZ Patients Infected With H. Pylori; Registration date: 7 December 2022). This clinical trial is a single blind, placebo controlled, randomized clinical trial with inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: BMI ≥ 27; waist circumference for men ≥90 cm, women ≥80 cm; body fat for men ≥25%, women 30%; a 13C urea breath test (UBT) test value > 10% indicating H. pylori positivity; and clinical dementia rating (CDR) = 0.5 reviewed by a psychiatrist at Chung Shan Medical University Hospital. Exclusion criteria were as follows: BMI < 27; severe chronic disease (liver disease, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease); taking medications known to affect lipid metabolism or possess anti-inflammatory effects; gastrointestinal disorder; surgery; alcohol abuse; smoking; pregnant or lactating; taking berry-related supplementation or having known allergies or hypersensitivity to berries, including BRBs; taking antibiotics/ corticosteroids in the last 4 weeks; taking NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors due to external clinical conditions; and/or prior history of H. pylori infection treated with triple therapy. Every subject enrolled in this study were asked to sign an informed consent before the start of the study.

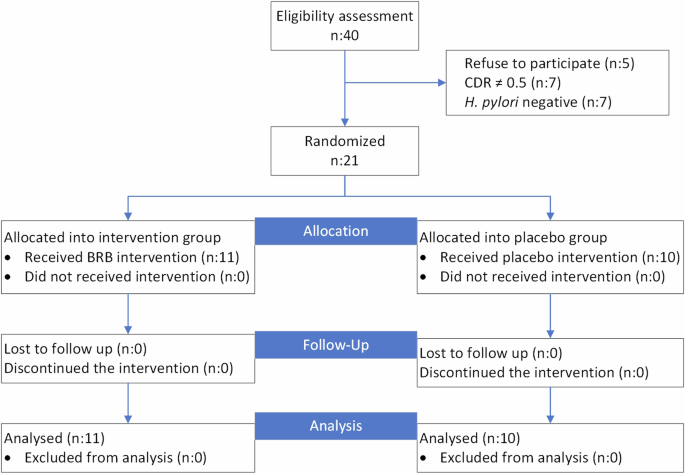

Subjects were recruited from August 2021-December 2021 from Chung Shan Medical University Hospital with the help of dr. Ming-Hong Hsieh. Subject recruitment was ended until 2 times of minimum subject number was achieved. In total, 21 subjects were recruited for the study and randomized using SAS statistical software to generate random allocation sequence (done by Dr. Chin-Kun Wang) and divided by block randomization with block size of 2 to achieve 1:1 ratio; 11 (8 males and 3 females) in the berry group and 10 (4 males and 6 females) in the placebo group. The participant flowchart from assessment until randomization can be seen in Fig. 1. Subjects were aged 60–85 years old. Those in the BRB group received 25 g of black raspberry powder dissolved in 240 mL of water twice a day, once after breakfast and once after dinner, resulting in total consumption of 50 g of black raspberry powder per day. Subjects in the placebo group received 25 g of dextrin twice per day, administered in the same way as the black raspberry powder to a total of 50 g of dextrin per day. Both samples were visually and organoleptically similar to each other to ensure the blinding of the subject. Each 50 g of black raspberry powder was estimated to contain (mean ± SD) 1926.50 ± 547.00 mg/g of phenols, 336.50 ± 11.00 mg/g of flavonoids, 1101.50 ± 51.00 mg/g of anthocyanins, 5581.00 ± 715.00 mg/g of condensed tannins, and 10.49 g of fiber (Supplementary Table 1).

Subject flowchart showing flow of participants from eligibility assessment through randomization to two intervention groups.

The study was conducted over 10 weeks, consisting of an 8-week intervention period and a 2-week follow-up. At week 0, anthropometric measurements were taken of weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference, blood pressure, body fat, and triceps skinfold thickness. Patients were asked to maintain their regular diets while on trial, and they kept a 3-day dietary record consisting of 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day. Blood sampling was also taken to assess lipid profile, cytokine levels, inflammatory markers, antioxidant index, thyroid function, liver function, kidney function, and blood chemistry. A 13C UBT, fecal sampling, and CDR were also performed at week 0. At week 2, anthropometric measurements and dietary recall were repeated. At week 4, anthropometric measurements, dietary recall, and blood sampling were performed. At week 6, anthropometric measurements and dietary recall were performed. At week 8, anthropometric measurements, dietary recall, blood and fecal sampling, and 13C UBT and CDR were performed. At the week 10 follow-up, anthropometric measurements, dietary recall, and blood sampling were performed.

Blood analysis

Blood analysis for inflammatory indicators (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8, COX2, iNOS), antioxidant function (SOD, Catalase), and blood biochemistry parameter was done using appropriate ELISA kit by following the manufacturer’s protocol. Each sample was tested in triplicate.

Plasma antioxidant capacity measurement

Plasma antioxidant activity was measured as the scavenging activity of ABTS free radical. An equal volume of 7 mM ABTS solution and 2.45 mM ammonium persulfate were mixed to generate stable ABTS free radicals in dark, room temperature overnight. 190 µL of ABTS free radical were reacted with 10 µl of plasma/standard for 1 min and absorbance was measured at 734 nm. Trolox was used as the standard and plasma antioxidant capacity was expressed as µM Trolox equivalent/mL.

Lipid peroxidation index

Lipid peroxidation measurement was done based on the formation of thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARS) from the reaction of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and malondialdehyde (MDA) which is a product of lipid peroxidation. Under acidic conditions, TBARS produces a red-pink color which can be measured spectrophotometrically at 532. 125 µL of plasma were mixed with 250 µL of 10% Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and 10 µL of 10% BHT then the mixture was centrifuged (5000 rpm, 4oC, 10 min). 200 µL of supernatant was mixed with 200 µL of TBA (375 mg in 75 mL 0.25 N HCl) and heated at 90oC for 30 min. The mixture the cooled in ice for 10 min and the absorbance was measured at 532 nm. TMP (1,1,3,3-Tetramethoxypropane) is used as the standard.

Fecal sample analysis

Fecal samples from the subjects who consumed BRBs were collected at baseline and end of the intervention. The fecal sample is prepared in the Colon Heal bacterial detection kit (Aging and Disease Prevention Research Center, Fooyin University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. 16S library pool was performed using Illumina MiSeq system library preparation instruction. Initial PCR were done using 16 s forward (F)/reverse (R) primers (F: 5’-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3’/R: 5’-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3’) using 2x Kapa HiFi hotstart ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems Ltd., London, UK) with cycle condition were 95 °C (3 min), then 25 cycles of 95 °C (30 s), 55 °C (30 s), 72 °C (30 s), then final extension of 72 °C (5 min). The pooled library was purified using AMPure XP beads to remove the primers. The second step of PCR was done with the addition of dual indices and Illumina sequencing adapters from the Illumina Nextera XT index kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA) with cycle conditions were 95 °C (3 min), then 8 cycles of 95 °C (30 s), 55 °C (30 s), 72 °C (30 s), then final extension of 72 °C (5 min). AMPure XP beads purification after the second step of PCR was done to clean the collected library before quantification. The generated 16 s library was quantified, diluted, and denatured before sequencing according to the Illumina MiSeq library preparation guide. The sequencing was done on Illumina MiSeq with MiSeq V3 reagent kits and analyzed with MiSeq Reporter Software (MSR). Classification of the result is based on the Greengenes database (http://greengenes.lbl.gov/). The mean of relative abundance was compared at the phylum, genus, and species levels.

Preparation of different BRB extracts

Procedures to prepare BRB crude extract, crude extract treated with gelatin, and tannins fraction are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Phenolic contents in different BRB extracts are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

AGS cell model

Human gastric adenocarcinoma cell culture (AGS cell) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in F12 (Ham’s media Kaighn Modification, Cytiva) medium containing 10% of Fetal Bovine Serum 37 °C humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Cell viability

The cell viability was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method. AGS cells (2 × 105 /mL) were seeded into a 96-well plate and incubated overnight. Increasing concentrations of BRB crude and gelatin-treated crude extracts (0, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000 µg/mL in serum-free medium with 0.05% Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO)) or H. pylori (OD600 0.3 (1 × 108CFU/ mL)) were co-cultured with AGS cells and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After 24 h, the medium was removed and changed with 100 μL (0.5 mg/mL) of MTT in phosphate-buffered saline (1X PBS) and cultured at 37 °C for 3 h. Finally, the cells were mixed with 100 μL DMSO and shaken for 10 min (to dissolve formazan crystals), and the absorbance was measured using a microplate reader at 570 nm. The blank wells were prepared with no cells and positive control wells were 50 µg/mL Amoxicillin. The cell viability (%) was calculated with the following equation:

Cell viability (%) = Absorbance (Sample − Blank)/ Absorbance (Control − Blank) × 100%

H. pylori adhesion

AGS cells were seeded in 24-well plates and incubated overnight. Increasing concentrations of BRB crude and gelatin-treated crude extract (0, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000 µg/mL) or amoxicillin (0.05 mg/mL) and H. pylori suspension were added to each well and incubated for 6 h in a humidified CO2 incubator. The nonadherent bacteria were washed off with 1X PBS solution. The final suspension was collected after 6 h of incubation to quantify the bacterial viability in the urease reagent and read at 560 and 600 nm. Adherent bacteria were evaluated with urease reagent (3 mM PBS pH 5.8; 2% urea and 4 µg/mL phenol red, pH 5.0) and read absorbance at 560 nm and calculated by the formula:

Anti-adhesive activity (%) = (control absorbance − sample absorbance)/control absorbance × 100%

CagA, VacA expression by western blot

Analysis of CagA and VacA expression detected using western blot analysis. AGS cells were seeded in 10 cm dish plates and incubated overnight. Increasing concentrations of BRB crude and gelatin-treated crude extract (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mg/mL) or amoxicillin (0.05 mg/mL) and H. pylori suspension were added to each plate and incubated for 6 h. All cells were collected and lysed using ice-cold lysis buffer, and cell protein was collected after centrifugation (3000 RPM, 10 min, 4 °C). Cell proteins were separated in 8% polyacrylamide gel and blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PVDF). The membrane was blocked in 5% skim milk in TBS buffer containing 0.2% Tween-20. The membrane was incubated with an anti-beta actin monoclonal antibody (SC-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), anti-CagA monoclonal antibody (SC-28368, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), and anti-VacA monoclonal antibody (SC-32746, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) overnight at 4 °C. After the removal of the primary antibody, the membrane was soaked in HRP-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Thermo Fischer, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The reactant band of the targeted protein was revealed using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) using an ECL commercial kit (G-Biosciences, USA).

IL-8 secretion

IL-8 content was determined using a commercialized IL-8 ELISA kit (Biolegend, California, USA) by following the manufacturer’s protocol. Each sample was tested in triplicate.

3T3-L1 cell model

3T3-L1 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in DMEM (Gibco) medium containing 10% bovine calf serum and differentiated into mature adipocytes by DMEM containing 0.5 mM IBMX (3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine), 1 mM DEXA and 10 mg/mL insulin at 37 °C humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Cell viability of 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes

The cell viability was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method. 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes were seeded into a 96-well plate and incubated overnight. Increasing BRB crude extract concentration, gelatin-treated crude extract, and tannin fraction (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, and 20 mg/mL) were added and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After 24 h, the medium was removed and changed with 100 μL (0.5 mg/mL) of MTT in phosphate-buffered saline (1X PBS) and cultured at 37 °C for 4 h. Finally, the cells were mixed with 100 μL DMSO and shaken for 10 min (to dissolve formazan crystals), and the absorbance was measured using a microplate reader at 570 nm. The blank wells were no cells. The cell viability (%) was calculated with the following equation:

Cell viability (%) = Absorbance (Sample − Blank)/Absorbance (Control − Blank) × 100%

Oil-red staining in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes for lipid accumulation

Mature adipocytes in 24 wells were washed twice with PBS and fixed using 10% formaldehyde solution for 1 h. After 1 h, cells were washed twice using PBS, and 0.5% oil red solution (in isopropanol) was added and incubated for 15 min to stain the lipid droplets. Cells were washed with dd H2O to remove unbound oil red. Isopropanol was added to dissolve the oil red and shake for 10 min. 100 μL of the solution was transferred to 96 wells, and read absorbance at 490 nm and lipid accumulation were calculated with the following equation:

Lipid accumulation (%) = Absorbance (Sample)/ Absorbance (Control) × 100%

HT-22 cell model

HT-22 cells (mouse hippocampal cell line) were cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Gibco) containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were incubated in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Cell viability

The cell viability was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method. Ht-22 cells (0.8 × 105 /mL) were seeded into a 96-well plate and incubated overnight. BRB crude extract (100 µg/mL) and/or amyloid β peptides (1.25 μM) were co-cultured with Ht-22 cells and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After 24 h, the medium was removed and changed with 100 μL (0.5 mg/mL) of MTT in phosphate-buffered saline (1X PBS) and cultured at 37 °C for 3 h. Finally, the cells were mixed with 100 μL DMSO and shaken for 10 min (to dissolve formazan crystals), and the absorbance was measured using a microplate reader at 570 nm. The blank wells were prepared with no cells and positive control wells were 50 µg/mL Amoxicillin. The cell viability (%) was calculated with the following equation:

Cell viability (%) = Absorbance (Sample − Blank)/Absorbance (Control − Blank) × 100%

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated to assess the difference among groups (α: 0.05) with a 5% reduction of UBT value using a 95% confidence interval and 80% power (1-β) and according to calculation each group needed at least 6 subjects and considering dropout rate of 25%, 10 subjects in each group is used. Repeated measure ANOVA and chi-squared test are used to assess differences within the group (intervention vs baseline) as appropriate. Results obtained from cells were analyzed with one-way ANOVA of SPSS (version 26, SPSS Inc). Significance difference is identified with p < 0.05.

Results

BRB consumption improves cognitive function in patients with mild dementia associated with decreased inflammation and oxidative stress

We conducted a placebo-controlled clinical trial in patients with mild clinical dementia due to AD who also had H. pylori infection and were overweight (aged 60–85 years old.). The baseline patient demographics show that age, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), body mass index (BMI), and urea breath test (UBT) are statistically the same (Table 1).

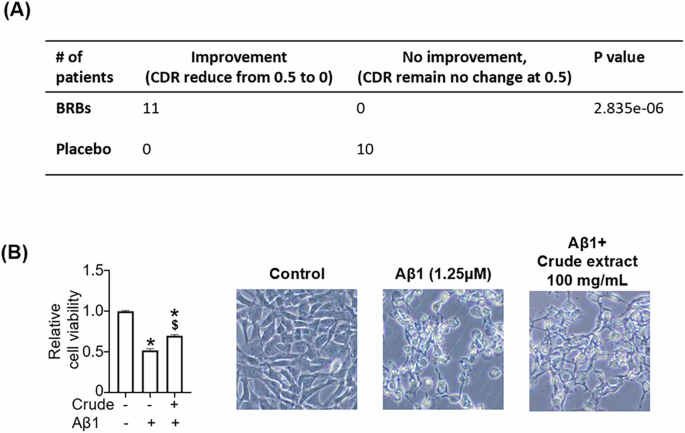

Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) values did not change in the placebo group, but those in the BRB group had an average CDR of 0 at the end of the 8-week intervention (Fig. 2A). It should be noted that neither amyloid beta nor p-tau was detectable in plasma from this patient population using an ELISA-based assay (data not shown). We then determined the effects of BRBs on Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in cultured neurons. Aβ42 oligomer treatment led to neurotoxicity in HT-22 neuron cells, and BRB ethanol extract protected against Aβ-induced damage (Fig. 2B). Ethanol extract of BRBs may contain anthocyanins that have been shown to cross the blood-brain barrier to protect the brain from Aβ toxicity (35).

A At baseline, BRB and placebo had clinical dementia rating (CDR) scores at 0.5. 8-week BRBs significantly moved CDR to zero, but the placebo group remained the same. B BRB crude extract rescued Aβ-induced cytotoxicity in HT22 cells. *p < 0.05: compared with untreated.

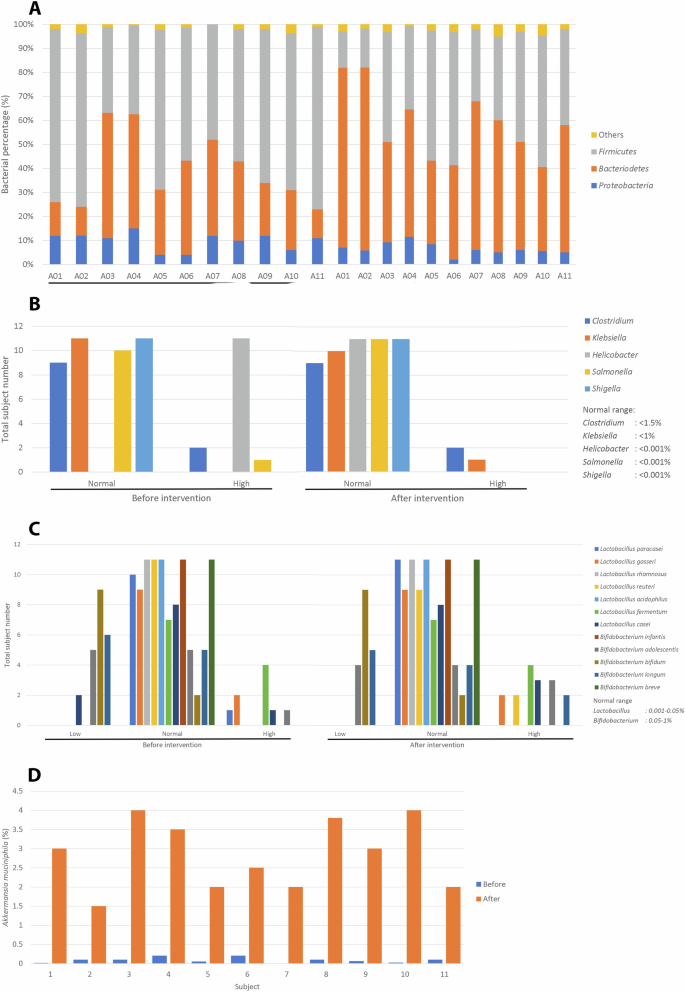

BRBs decreased Proteobacteria and Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio in the feces (Fig. 3A).

A Stool Proteobacteria analysis. B Stool pathogen analysis. C Stool probiotics analysis. D Stool Akkermansia muciniphila analysis.

Further, BRBs decreased fecal Helicobacterbacteria abundance (Fig. 3B), but increased fecal probiotics such as Lactobacillus reuteri, and Bifidobacterium longum (Fig. 3C). Most interestingly, Akkermansia muciniphila abundance increased in all subjects who consumed BRBs (Fig. 3D).

13C UBT was significantly lower at week 8 in the BRB group when compared to baseline (Table 2). However, this difference was resolved in week 10. Inflammatory markers, reflected by tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-8 (IL-8), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) were measured at weeks 0, 4, and 8. At week 4, levels of TNF-α, IL-8, COX-2, and iNOS were significantly lower than at baseline, whereas levels of IL-1β were significantly higher. At week 8, levels of TNF-α, IL-8, and COX-2 were significantly lower than baseline, with IL-1β continuing to be significantly higher than levels at both baseline and week 4. The oxidative index was quantified by superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), and Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC). At weeks 8 and 10, SOD, CAT, and TEAC levels were significantly higher than at baseline, but TBARS levels were significantly lower than at baseline.

Regarding changes in BMI, at week 4, the BRB group had a significantly lower body weight and BMI (p < 0.05) compared to their week 0 measurements (Table 3). Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and leptin did not significantly change from baseline across the course of the study, but adiponectin was significantly increased from baseline at both weeks 8 and follow-up (p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Further, neither the BRB nor placebo groups had significant changes in blood lipid profile from their respective baselines at these time points (Supplementary Table 2). Insulin, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance score (HOMA-IR, quantified as [FBG * insulin]/405), and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1C) did not significantly change from baseline in the BRB and placebo groups (Supplementary Table 3). However, FBG was significantly higher compared to baseline at week 4 and week 8 in the BRB group (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, respectively). Blood chemistry of subjects, reflected by glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (GOT), glutamate pyruvate transaminase (GPT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, uric acid (UA), and creatinine phosphokinase (CPK), were not significantly different in either group across time points (Supplementary Table 3). Mineral content was reflected by sodium (Na), potassium (K), chloride (Cl), and calcium (Ca) levels. K levels were significantly higher at week 4 compared to baseline in the BRB group (p < 0.01) (Supplementary Table 4). Na was significantly lower at follow-up compared to baseline in the BRB group (p < 0.05).

At week 4, those in the BRB group had a significantly lower rump circumference (RC) and triceps skin fold (TSF) (p < 0.05) compared to their week 0 measurements (Supplementary Table 5). At week 8, those in the BRB group had a significantly lower body fat percentage, RC, and mid-arm circumference (MAMC) compared to their week 0 measurements (p < 0.05). Aside from these differences, waist circumference (WC), RC, MAMC, and TSF were not significantly different within the two groups at various recording times. At week 4, DBP was significantly lower than the baseline in the BRB group (p < 0.05). While this difference resolved, SBP became significantly lower from baseline in the BRB group at follow-up (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 6).

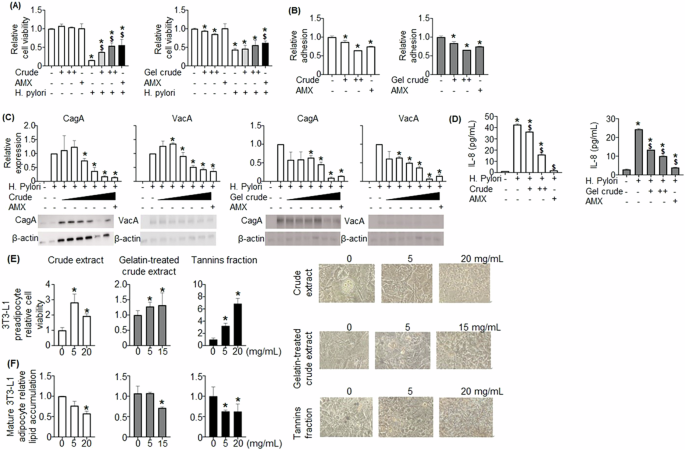

BRB extracts rescued H. Pylori-induced damages in cultured AGS cells

An MTT assay was performed on applying crude BRB extract to AGS cells and H. pylori to assess for protective effects of BRBs against H. pylori, with cell viability assessed at 24 h (Fig. 4A). When H. pylori was added with no BRB extract or amoxicillin, cell viability decreased at 24 h. However, when increasing concentrations of crude BRB extract were added to H. pylori and the AGS cells, cells were rescued. A similar effect was seen with the gelatin-treated crude extract. H. pylori adhesion was measured with varying doses of crude and gelatin-treated crude extracts. Increasing doses of crude and gelatin-treated crude extract reduced H. pylori adhesion (Fig. 4B).

AGS cells were treated with crude extract and gelatin-treated crude extract, and cell viability (A), H. pylori adhesion (B), CagA and VagA protein expressions (C), and IL-8 level (D) were evaluated. E Three BRB extracts, crude extract, gelatin-treated crude extract, and tannins fraction, enhanced cell viability of 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes and (F) decreased lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 mature adipocytes. A +: 50,++: 500 ug/mL, B +: 50,++: 500 ug/mL, C +: 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000 ug/mL, D +: 50, ++: 500 ug/mL. *p < 0.05: compared with untreated, $p < 0.05: compared with H. pylori treated.

Analysis was performed on proteins associated specifically with H. pylori. Western blot was performed to assess the expression of cytotoxin-associated protein A (CagA), associated with the induction of intestinal metaplasia and gastric adenocarcinoma20. CagA expression was significantly reduced by both crude and gelatin-treated crude extract (Fig. 4C). Western blotting was also utilized to determine the expression of vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), another H. pylori product that modulates the function of immunologic cells and is associated with H. pylori colonization, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric adenocarcinoma21. VacA expression was significantly decreased by crude extract and crude extract treated with gelatin (Fig. 4C). Lastly, interleukin-8 (IL-8) expression has been shown to be induced by H. pylori infection; the upregulation of IL-8 related to H. pylori is associated with gastritis and possibly gastric malignancies22,23. When H. pylori was added to the AGS cell culture, IL-8 expression was significantly increased (Fig. 4D). Both extracts significantly decreased H. pylori-induced IL-8.

Overall, both crude extract and crude extract treated with gelatin decreased H. pylori-induced damages, including increasing cell viability, decreasing H. pylori adhesion and expression of CagA, VacA, and IL-8 in cultured AGS cells (Fig. 4A–D).

BRB extracts promoted 3T3-L1 pre-adipocyte viability and decreased lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1c mature adipocytes

3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes were incubated with crude extract, gelatin-treated crude extract, and tannin fraction. A significant increase in viability was seen in 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes treated with all three extracts (Fig. 4E). Oil-red staining was then performed to assess the effects of those three extracts on lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 mature adipocyte cells. All three BRB extracts significantly decreased lipid accumulation (Fig. 4F).

Discussions

The purpose of this study was to assess whether BRBs had meaningful effects on markers of H. pylori infection and obesity, thereby impacting AD dementia. We conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial, which examined the effects of BRBs on obese subjects who were H. pylori positive and had AD as measured by a CDR of 0.5. BRBs significantly improved cognitive function by moving CDR from 0.5 to zero and decreased UBT and BMI. These effects are associated with significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capacity.

Although neither amyloid beta nor p-tau was detectable in plasma from this AD patient population using an ELISA-based assay (data not shown), our results could suggest that they could be at an early stage of AD. More sensitive ultrasensitive platforms, including SIMOA, IMR, MSD, and Elecsys immunoassays, that overcome the complex interferences of blood proteins, heterophilic antibodies, and low target biomarkers24, will be used to confirm the levels of blood amyloid beta and p-tau in this AD population in the future.

Gut microbiota is a complex microorganism in the human GI tract that plays a crucial role in maintaining health25. Gut microbiota can help to metabolize some indigestible dietary components and prevent pathogen colonization in the GI tract26. Gut microbiota mainly comprises two major phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, and some minor phyla, such as Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria27. Alteration of gut microbiota can influence different metabolic disorders, the immune system, and also the central nervous system through the gut-brain axis28. Recent studies show that there are links between gut microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease. Gut microbiota is affected by lifestyle, including food intake and habits. Host dietary components are used as substrates and energy sources to prevent pathogenic bacteria and produce beneficial metabolites29. Proteobacteria is one of the gut microbiota phyla that comprises several human pathogens30. Pathogenic infections such as Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, Toxoplasma gondii, and others might contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease31. Besides Proteobacteria, gut dysbiosis is linked to AD progression. Gut dysbiosis is a phenomenon where gut microbiota is altered mainly showed by an increasing ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes32,33. Gut dysbiosis is associated with several AD pathologies, such as accumulation of intestinal amyloid precursor protein (APP), induction of systemic inflammation by proinflammatory neurotoxin and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and alteration of the blood-brain barrier (BBB)33,34,35,36.

BRBs contain high amounts of polyphenols which can act as antimicrobial agents, especially for H. pylori37,38. Helicobacter, particularly Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that mainly resides in the gastric and induces several inflammatory responses due to its virulence factor39. H. pylori infection can disrupt tight junctions, and this disruption can lead to increased proinflammatory cytokines and harmful metabolites (e.g. bacterial amyloids and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO))40. These harmful substances produced by pathogens enter the circulatory system, disrupt BBB, and induce an immune response in the central nervous system33. H. pylori can induce a neuroinflammatory response in the C57BL6 WT mice through circulating proinflammatory cytokines41. Eradication of H. pylori from AD subjects results in improved cognition compared with AD patients who did not receive H. pylori eradication therapy42.

On the other hand, BRB intervention also increased probiotics concentration in the GI tract. Probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium play an essential role in maintaining gut health due to their ability to metabolize undigested food components and produce metabolites such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and short-chain fatty acids (SCFA)43. Another probiotic known as Akkermansia muciniphila is a gram-negative bacterium belonging to Verrucomicrobiota, constituting 1–4% of the total fecal microbiome44,45. Akkermansia muciniphila can degrades intestinal mucin and produces acetate and propionate as substrates for other gut microbiomes and the host46. According to our study, BRB treatment induces the growth of probiotics inside the GI tract including Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Akkermansia muciniphila. The increased growth of probiotics is negatively correlated with inflammation. Probiotics act by modulating gut functions and immune response thus reducing inflammation47. Our study result shows that BRBs treatment increased probiotics abundance and decreased the inflammatory markers such as IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α, and COX-2. According to past studies, polyphenols promote the growth of probiotics such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Akkermansia muciniphila which positively affect inflammation and suppress the growth of pathogens including H. pylori48,49,50,51,52,53. Probiotics also have been proven to suppress the progression of the neurodegenerative disease through the GBA signaling54. Metabolites from probiotics such as GABA and SCFA act as neurotransmitter modulator that regulates brain function, affect neuron health, and mitigate neurodegeneration55. Akkermansia muciniphila has been shown to have a beneficial effect against AD in animal models by reducing Aβ accumulation and improving cognitive function56. Our data shows the increase of Akkermansia muciniphila abundance in subjects who receive BRBs treatment this increase of abundance is also negatively correlated with CDR value change in the BRBs treatment group. A study from McLeod et al. shows a positive correlation between the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila and cognitive function showing the beneficial effect of this bacterium on cognitive function57.

UBT values and inflammatory markers provided indices of efficacy against H. pylori infection. Overall, UBT values were meaningfully improved by BRB intervention, but this effect did not persist when BRB supplementation was discontinued. While most of the inflammatory markers, excluding iNOS, did indicate less inflammatory profiles with continued BRB supplementation, the post-intervention impacts were not explored, so additional study is needed to assess whether the alterations in inflammatory profile continue to benefit even after BRB treatment. These results indicate that BRBs may exert some degree of defense against H. pylori infection, but the results only support these benefits so long as BRBs continue to be consumed in the diet.

Assays were performed first on AGS and 3T3-L1 pre-adipocyte cell models to explore whether BRBs might have tangible results in human patients. While BRBs significantly improved the viability rates of AGS cells exposed to H. pylori. Further, both crude and gelatin-treated crude extracts reduced the adhesion rates of H. pylori in the AGS cell cultures. However, here it is important to note that the amoxicillin control also showed the same level of a significant reduction in adhesion rates as BRBs, suggesting that BRBs were similarly, but not more or less effective, than amoxicillin alone in reducing adhesion rates of H. pylori. Both crude extract and crude extract treated with gelatin decreased CagA and VacA protein expressions. These results suggest that while BRB extract can provide statistically comparable effects when compared to amoxicillin in reducing the expression of these H. pylori genes, it must be administered at sufficiently high doses. However, considering that amoxicillin is currently part of status quo treatment for H. pylori based on extensive research demonstrating its effectiveness, further research is needed to determine whether BRBs are a reasonable alternative to amoxicillin, seeing as they do appear to provide a significant additional benefit against H. pylori infection in AGS cells. Another route of exploration may involve seeing if the effects of amoxicillin and BRBs are cumulative; that is, whether the supplementation with BRBs of a pre-established amoxicillin regimen to treat H. pylori might be more effective than amoxicillin alone.

The 3T3-L1 pre-adipocyte and mature adipocyte models, crude extract, gelatin-treated crude extract, and tannins fraction were all effective. This result supports the notion that crude BRB extract is sufficient to show the effects. Tannins in the extract are essential. Gelatin-treated crude extract or tannins fraction and that more components than just tannins are likely active in reducing lipid accumulation. It is expected that the effects of crude BRB extract cannot be attributed to tannins alone. Still, more research will be needed to determine which additional components confer the other advantage to crude BRB extract.

Given the activity of BRBs against H. pylori, as demonstrated by the AGS cells, and against obesity, as shown by the 3T3-L1 pre-adipocyte cells, it was anticipated that they might exert similar effects on actual patients. Although BRBs did affect physiologic markers of obesity, including body weight, BMI, body fat, RC, MAMC, and TSF, these effects did not persist into the follow-up stage. Interestingly, while body fat, RC, and MAMC did a downtrend throughout the intervention, reaching significance by week 8, the other markers did not show trends with continued intervention. This finding suggests that adding BRBs to the diet provided variable benefits, with some lasting only temporarily despite additional BRB consumption and others taking some time to manifest. Overall, all benefits were lost within 2 weeks after the intervention was concluded, so continued consumption of BRBs appears to be necessary. BRBs did not confer any significant disadvantage as assessed by the obesity markers.

Interestingly, SBP only showed a significant reduction at follow-up, 2 weeks post-intervention, while DBP was only reduced at week 4. BRBs did not exert meaningful effects on blood lipid profiles. They did not affect markers of diabetes other than fasting blood glucose, which was significantly increased with an upward trend throughout the intervention. This trend merits further exploration as increased FBG is not a desirable result; while the average levels within subjects were maintained below pre-diabetes levels, it is uncertain whether continued consumption of BRBs would have breached that threshold. One of the most significant changes related to obesity was seen in adiponectin levels, which substantially increased after both 8 weeks of treatment and 2 weeks post-intervention. Low adiponectin levels are associated with obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other conditions that place patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease, while high adiponectin levels are associated with a healthier metabolic profile, so it appears that BRBs resulted in a meaningful benefit here58,59.

This study only limited to subject who lives in Taiwan and cannot be generalized to other race and ethnicity. Another limitation was the subject enrolled in this study have CDR value of 0.5, the finding might be different for subject who have CDR value > 0.5.

In conclusion, our results provide the first evidence that BRBs enhanced fecal Akkermansia muciniphila abundance and protectively altered parameters of H. pylori infection and obesity, leading to dampened inflammation and oxidation. BRB treatment could result in improved cognitive functions in mild dementia subjects. Longer and larger randomized clinical trials of BRB interventions targeting H. pylori infection, obesity, or AD are warranted to confirm the results from this pilot trial.

Responses