Black Tea drinks with inulin and dextrin reduced postprandial plasma glucose fluctuations in patients with type 2 diabetes: an acute, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blind crossover study

Introduction

Optimization of glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients has been shown to reduce the complications of diabetes [1, 2]. According to a meta-analysis, there are strong associations of postprandial hyperglycaemia with cardiovascular disease risk and prognosis, and postprandial hyperglycaemia is an independent predictor of diabetic mortality and cardiovascular complications [3]. It is recommended that patients with T2DM be treated in a way that reduces glycaemic changes, particularly acute glucose swings [4].

It is recommended that the diet for glycaemic control be rich in dietary fibre [5]. A meta-analysis of 35 RCTs found that psyllium fibre caused a significant lowering of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and postprandial glucose in individuals with T2DM [6]. The black tea powder used in the present study contains two kinds of water-soluble dietary fibre: resistant dextrin and inulin. Inulin is a mixture of fructooligosaccharide, which is a linear fructose polymer (degree of polymerization [DP], 2–60), and β (2 → 1) glycosidic linkages [7]. Resistant dextrin is defined as short-chain glucose polymer rich in α-(1 → 4) and α-(1 → 6)-glycosidic bonds that is usually produced by dextrinisation and repolymerisation of maize or wheat starch [8]. Resistant dextrin and inulin are nondigestible, fully soluble, and resistant to the hydrolytic effects of digestive enzymes in humans [9, 10]. These functional fibres are conducive to weight loss and improve glucose and lipid metabolism [11, 12].

However, no studies have investigated the effects of black tea drinks with inulin and dextrin (BTID) on T2DM. Thus, we conducted an acute randomized controlled crossover trial to compare the independent and combined effects of normal black tea powder versus BTID consumed before breakfast on postprandial glycaemic and insulinemic responses. We focused on breakfast because the typical intakes of fibre at this meal are lower than at lunch and dinner. In addition, some previous studies suggest that higher fibre intake at breakfast may have favourable metabolic effects by enhancing insulin-mediated glucose disposal through increased insulin secretion [13, 14]. We hypothesized that consumption of BTID, which has high levels of fibre, at breakfast would lower postprandial glucose.

Material and methods

Study design

An acute, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blinded crossover study was carried out during which background glucose-lowering therapy was unchanged. This study was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (approval number: ChiCTR2300068985). All eligible patients were informed about the study and provided consent. We obtained approval from the hospital ethics committee before beginning patient recruitment.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Endocrine Clinic of our hospital. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 18–80 years old, diagnosed with T2DM based on the WHO criteria (FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, 2 h plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or glycated haemoglobin [HbA1c] ≥ 48 mmol/mol [6.5%]); body mass index (BMI) ≥ 18.5 kg/m2, HbA1c ≥ 53 mmol/mol [7.0%], FPG ≤ 13 mmol/L. The exclusion criteria were acute and chronic gastrointestinal conditions, such as peptic ulcer, or hernia; hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, uncontrollable hypertension, or hepatic or renal insufficiency (alanine transaminase [ALT], aspartate transaminase [AST], or serum creatinine (Scr) 1.5 times above upper limit of normal); pregnancy or brittle diabetes; any acute infection; myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery, or stroke within the previous 3 months; any mental disorder; drug or alcohol misuse; and an allergy to any of the medications used in the study. The minimal number of patients was calculated to be 30 to draw significant conclusions under the conditions of α = 0.05 and power = 90%.

Randomization and allocation

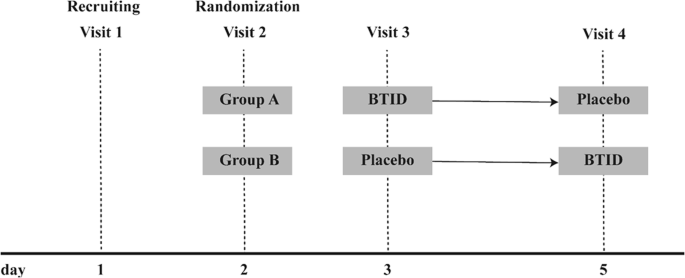

At visit 2, eligible participants were randomly divided into groups A and B (Fig. 1). At visits 3 and 4, they visited the Clinical Trial Center of our hospital at 08:00 after an overnight (10 h) fast and underwent the mixed meal tolerance test (MMTT), involving 100 g steamed bread and one egg (~ 50 g). Participants were asked to take placebo black tea powder or BTID in 300 mL warm water within 10 min with the MMTT. Group A consumed BTID before the MMTT at visit 3 and placebo at visit 4, while group B consumed placebo before the MMTT at visit 3 and BTID at visit 4. After measuring height and body weight, an 18-gauge indwelling intravenous catheter was placed in the forearm. Venous blood samples were collected at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min during the MMTT. Serum and plasma were separated immediately by centrifugation at 1500 rpm (4 °C) for 15 min and stored at -80 °C until analysis. Participants were instructed to maintain their usual dietary and exercise habits, refrain from changing their medication regimen, and avoid any significant changes throughout the study.

BTID black tea drinks with inulin and dextrin.

Dosage information

Subjects received placebo black tea powder (0.92 g, provided by Methuselah medical technology (shanghai) co. LTD) or BTID (identically packaged) (2 g, provided by Methuselah medical technology (shanghai) co. LTD). Each 100 g of BTID contained 50 g of dietary fibre (resistant dextrin and inulin), with ingredients listed as 46% black tea powder.

Anthropometric and laboratory assessments

All subjects completed a questionnaire about their demographics and health (such as age, drinking of alcohol history, and medical history). During the physical examination, participants’ height, weight, waist circumference, hip circumference, and blood pressure were all taken. Body weight was measured without shoes while wearing light clothing to the nearest half kilogram. Height, waist and hip circumferences of each subject were measured to the nearest centimeter. BMI was calculated as body mass/ height2 (kg/m2). Blood pressure (BP) was measured three times at five minutes intervals by an experienced physician with a mercury sphygmomanometer on their left arm, feet on the floor and arm supported at heart level after at least 10 min of rest.

The study participants were instructed to maintain fast for ten hours. Venous blood samples were collected for the measurement of white blood cell count (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), Scr, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum uric acid (SUA), HbA1c, total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). And PG, serum insulin (INS), serum C-peptide (CP) at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min during the MMTT were measured. Plasma glucose concentrations were measured using the glucose oxidase method. HbA1c level was measured by high performance liquid chromatography (Variant II hemoglobin analyzer; Bio–Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Serum insulin levels were measured with an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on a Cobase411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Lipid profiles were assayed with a 7600-120 Hitachi automatic analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

In this study, Area under curve (AUC) of glucose and insulin were used for insulin measurements as follows: AUCGLU = [plasma glucose(fasting)+2*plasma glucose (30 min) +3*plasma glucose (60 min) +4*plasma glucose (120 min) +2*plasma glucose (180 min)]/4; AUCINS = [insulin(fasting)+2*insulin (30 min) +3*insulin (60 min) +4*insulin (120 min) +2*insulin (180 min)]/4.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS statistical software (ver. 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Comparisons of anthropometric parameters, glucose and lipid levels, PG, insulin, C-peptide (CP), and the area under curve of glucose and insulin after the MMTT between groups were conducted using paired t-tests. A threshold of 2.8 mmol/L (50 mg/dL) was used to categorize PG fluctuations at 2 h post-MMTT, with < 2.8 mmol/L indicating small fluctuations and ≥ 2.8 mmol/L indicating significant fluctuations. The proportions of participants experiencing significant PG fluctuations 2 h after consuming placebo and BTID during the MMTT were analysed using chi-square tests. Binary logistic regression was employed to compare the risk of significant PG fluctuations at 2 h post-MMTT (dependent variable) between the BTID and placebo groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

A total of 35 patients were included in the study, and 32 completed the study. The sex, age, anthropometric parameters, glucose and lipid metabolism levels of the enrolled patients are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in baseline FPG, fasting serum insulin (FINS), or fasting serum C-peptide (FCP) between the groups before consuming BTID and placebo.

Group differences in PG increase after MMTT

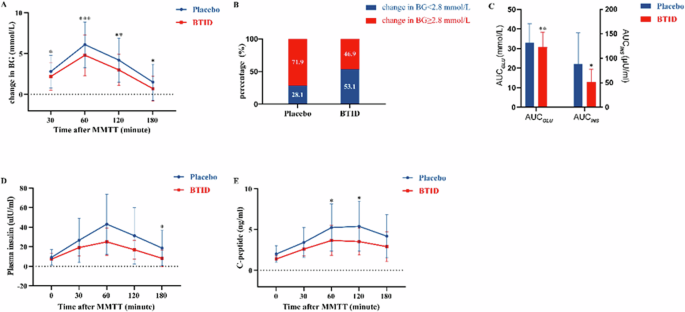

Compared to placebo, the increase in PG levels with BTID was smaller at 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h post-MMTT (Fig. 2A). Among the patients receiving BTID intervention, 53.1% had small PG fluctuations, compared to only 28.1% of those receiving placebo intervention, with a statistically significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 4.137, P = 0.042) (Fig. 2B).

A Changes in glucose after consuming BTID or placebo followed by MMTT. B Proportion of post-MMTT 2 h PG fluctuation situation after consuming BTID or placebo. C AUCGLU and AUCINS after consuming BTID or placebo followed by MMTT. D Changes in insulin after consuming BTID or placebo followed by MMTT. E Changes in C-peptide after consuming BTID or placebo followed by MMTT. (p-value * <‘ 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001). BTID black tea drinks with inulin and dextrin, MMTT Mixed meal tolerance test, PG plasma glucose, AUC area under curve.

Multivariate linear regression

Using the magnitude of PG fluctuations at 2 h post-MMTT as the dependent variable, binary logistic regression analysis revealed that, compared to placebo, the risk of significant PG fluctuations was reduced by 65.5% with BTID, with a corresponding odds ratio of 0.345 (P = 0.044, 95% CI 0.122–0.974).

AUCGLU and AUCINS

AUCGLU for BTID was (30.7 ± 7.7) mmol/L and the AUCINS for BTID was (51.4 ± 26.5) μU/ml whereas AUCGLU for placebo was (33.0 ± 9.7) mmol/L and the AUCINS for placebo was (88.6 ± 63.4) μU/ml. Both the AUCGLU and the AUCINS for BTID were significantly lower than those for placebo (t = 3.124, P = 0.004; t = −3.179, P = 0.034) (Fig. 2C).

Compared to placebo, the increase of insulin with BTID was smaller at 3 h post-MMTT (Fig. 2D), and the increase of CP with BTID was smaller at 2 h and 3 h post-MMTT (Fig. 2E).

Discussion

BTID resulted in smaller PG increments at 30, 60, 120, and 180 min post-MMTT. Furthermore, at 120 min, > 50% of the patients had insignificant PG fluctuations. Binary logistic regression analysis revealed that compared to placebo, the risk of significant PG fluctuations was reduced by 65.5% with BTID consumption. This study demonstrated that adding inulin and resistant dextrin to black tea drinks could more effectively stabilize postprandial PG levels compared to drinks without these additives. In addition, BTID reduced postprandial insulin secretion, thereby helping to improve insulin sensitivity and lowering β-cell burden.

Postprandial hyperglycaemia is a primary obstacle to achieving target HbA1c levels in diabetes management. The rapid absorption of glucose into the bloodstream following a meal causes a sharp increase in PG levels, which triggers a series of physiological and metabolic responses, including oxidative stress and endothelial damage. The cumulative effect of these responses over time can increase the risk of cardiovascular events [15, 16]. This issue is particularly pronounced among Chinese patients, who exhibit more significant postprandial hyperglycaemia [17]. The larger and more prolonged increases in postprandial PG levels seen in Chinese patients may be closely related to dietary habits, genetic factors, and lifestyle choices [18]. This hyperglycaemic state can negatively impact the cardiovascular system and overall health of patients. Therefore, actively managing postprandial hyperglycaemia is crucial for the long-term health of diabetes patients.

BTID, which contains inulin and resistant dextrin, reduced the change in PG levels following a glucose load and conserves postprandial insulin secretion. As soluble dietary fibres, inulin and resistant dextrin have been shown to have potential in PG control. Our findings are in line with previous research reporting that inulin lowers fasting and postprandial blood glucose (BG) levels [19,20,21,22].

Notably, while most studies have not reported a significant impact of inulin on postprandial insulin levels [21, 23, 24], some have found an association [22, 25]. These conflicting results may be related to the role of inulin in improving insulin sensitivity [12, 25]. Similarly, the use of resistant dextrin has been found to lower BG and insulin levels [26, 27]. Some studies have indicated that resistant dextrin may regulate BG metabolism by reducing insulin secretion and improving insulin resistance [11, 28, 29]. Our findings are consistent with research showing that when inulin and resistant dextrin are used together, they can synergistically lower fasting and postprandial BG levels and improve insulin resistance [30]. This synergistic effect may be due to the complementary mechanisms by which inulin and resistant dextrin affect glucose metabolism. In previous studies, this effect was partly attributed to the formation of a viscous gel in the gastrointestinal tract by inulin and resistant dextrin [31, 32], which slowed down the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates, thus delaying the increase in BG levels. In addition, both inulin and resistant dextrin may modulate glucose metabolism by regulating the secretion of incretin hormones in the gastrointestinal tract [27, 33]. These actions collectively impact insulin secretion and cellular responses thereto, thereby regulating BG metabolism.

Tea drinking is widespread in China, which is in fact known for its rich tea culture. Therefore, functional tea beverages can easily be integrated into the daily management routines of diabetes patients. Compared to placebo, BTID containing inulin and resistant dextrin significantly reduced postprandial PG change and postprandial insulin secretion. This suggests that both inulin and resistant dextrin may have the potential to improve insulin sensitivity. These findings provide new evidence supporting the potential application of inulin and resistant dextrin in PG management strategies.

In East Asian regions, breakfasts typically contain a high proportion of carbohydrates [34, 35]. This high-carbohydrate dietary habit, combined with the first meal following a prolonged overnight fast, leads to a significant rise in postprandial PG levels [18]. Compared to lunch and dinner, the PG increase after breakfast is more pronounced. Our study found that BTID can help reduce this post-breakfast PG spike, indicating that BTID can effectively reduce PG fluctuations after high-carbohydrate East Asian breakfasts. This aids in better glycaemic control, particularly for individuals with diabetes or those requiring stringent PG management.

This study employed a self-controlled design, effectively minimizing interindividual variability and interference effects. The single-blind crossover design further reduced the potential impact of subjective factors on the results, thereby enhancing the objectivity of the findings. However, this study also had several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the results; thus, cautious interpretation of the findings is warranted. Second, this is an acute study, and the follow-up period was relatively short, which hinders comprehensive assessment of the long-term effects of BTID on glucose metabolism. Finally, the absence of a blank control group and an inulin or dextrin-only control group prevents us from fully ruling out the potential influence of other factors on the study results. Future research should consider increasing the sample size, extending the follow-up period, and incorporating a more comprehensive control group to validate the reliability and clinical applicability of these findings.

Conclusion

Consumption of BTID, which leads to higher fibre intake at breakfast, has significant potential for postprandial glucose management. Compared to placebo, BTID reduced the change in PG levels and significantly decreased the risk of large PG fluctuations following the MMTT. This effect may help to improve postprandial insulin sensitivity. This finding provides strong support for the use of BTID at breakfast as an adjunctive tool in PG management and offers new directions for future research in this area.

Responses