Brine management with zero and minimal liquid discharge

Introduction

A substantial volume of saline wastewater (brine) is generated from desalination, energy, mining and semiconductor industries1,2,3,4,5,6, posing a prominent challenge to environmental sustainability and circular water economy. For example, the prohibitively high costs and environmental risks associated with treating and/or disposing reverse osmosis (RO) concentrate prevent the wide adoption of inland desalination as a viable means for addressing regional water scarcity7,8. Furthermore, brines with a wide spectrum of compositions are also generated from various industries and need to be properly managed for compliance and the sustainability of those industries1,7. Zero liquid discharge (ZLD), which aims to recover all the water for reuse and generate solid waste, has been proposed as an aggressive approach to eliminate hazardous brines and minimize the environmental impacts of brine discharge, while reducing water footprint via wastewater reuse7,9,10. Most ZLD processes have high operating costs associated with the large energy input, ultimately evaporating much of the feedwater and leaving behind low-moisture solid residuals. Developing cost-effective technologies for ZLD as a strategy for brine management has therefore attracted interest from both industry and academia.

Typical ZLD treatment schemes consist of a brine concentration step, which elevates the wastewater salinity to a near-saturation level (~250 g l−1 of total dissolved solids, TDSs)11, and a thermal crystallization step, which produces salt crystals for beneficial use or disposal7. Currently, ZLD processes dominantly rely on the energy-intensive and cost-intensive evaporative method of mechanical vapour compression (MVC) and the geographically constrained method of evaporation ponds7. RO, a mature and more energy-efficient concentrating technology relative to MVC1,12, is constrained by the salinity limit imposed by the maximum operating pressure of commercial RO systems and/or mineral scaling7,13. Therefore, there is a critical need to develop new technologies that tolerate higher salinity than conventional RO but with reduced cost and energy consumption compared with traditional evaporative methods.

Despite the development of novel materials and processes for ZLD during the past decade, several factors hinder the development and adoption of innovative technologies for cost-effective and energy-efficient ZLD. There are debates on whether ZLD is always the optimal solution owing to its high cost and energy consumption10. The necessity of ZLD depends on the quantity and chemical composition of wastewater, which vary between different industries. Minimal liquid discharge (MLD), an approach that involves brine volume reduction (BVR) and disposal, could be a more cost-effective strategy for managing brines in many scenarios14,15,16. The choice of ZLD or MLD treatment trains for specific applications has not been thoroughly examined and compared across brine-generating industries. Moreover, although several emerging ZLD technologies have shown the potential for improving energy efficiency of ZLD, it is uncertain whether these technologies can outcompete MVC as a core component of ZLD treatment trains in practical applications. Advancing brine management beyond the state-of-the-art requires a thorough framework to connect the treatment needs (or goals) with available treatment technologies.

In this Review, we discuss the application and prospects of ZLD and MLD in brine-generating industries. We describe engineered systems for BVR and crystallization and highlight the challenges for these emerging systems to outcompete the use of MVC and thermal crystallizers for brine concentration and crystallization. Finally, we review opportunities for brine valorization to potentially offset the cost of brine management and recover resources.

Defining zero and minimal liquid discharge

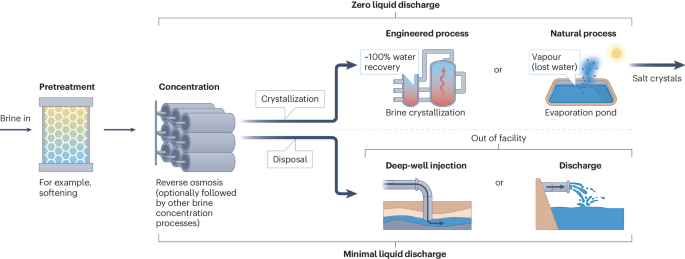

ZLD aims to eliminate liquid wastes within a plant or facility boundary by ideally removing or recovering 100% of the water and obtaining salt crystals as either a solid waste for disposal or a resource for valorization7. To achieve this ambitious goal, core treatment trains of ZLD include a brine concentrator (BC) that concentrates saline wastewater to near saturation, followed by a brine crystallizer (BCr) or an evaporation pond where salt precipitation occurs (Fig. 1). MVC is currently the state-of-the-art technology for BC, and thermal BCr follows a similar working principle7. The thermodynamic energy efficiency of MVC is lower than that of RO, which does not induce any phase change for water–salt separation1,17. Therefore, RO is often used as a pre-concentration step to reduce the volume of brine to be treated by the more energy-intensive BC and BCr7,9. In other words, a conventional treatment train of ZLD usually consists of RO, a BC and a BCr.

Zero liquid discharge (ZLD) and minimal liquid discharge (MLD) treatment trains typically involve a pretreatment step and a brine concentration step. The brine concentration step usually includes a reverse osmosis process and a brine concentrator. The concentrated brine can be sent to either an engineered process (such as a thermal brine crystallizer) or a natural process (such as an evaporation pond) for crystallization. The brine concentration step and the crystallization step combined comprise the ZLD treatment train. Alternatively, the concentrated brine can also be disposed via deep-well injection or discharge (to ocean or other allowable receiving water bodies). The brine concentration step and the disposal step combined comprise the MLD process.

MVC-based BC and BCr are not only energy-intensive but also expensive to build owing to the need of using costly materials (such as titanium alloy and stainless steel) to withstand the corrosive brines with high temperatures (above the brine boiling point) and salinities (at near-saturation level)18,19,20. According to industry data, the BCr step processes only 12% of the overall saline wastewater volume but is responsible for >40% of the total treatment cost21. Alternatively, brine crystallization can also be achieved using an evaporation pond. Evaporation ponds can replace BCr using natural evaporation driven by dry climate and solar radiation. However, the use of evaporation ponds requires large areal footprint and an arid climate and is constrained by its environmental risks and the cost due to the stringent requirements on liners and monitoring wells22,23,24. Importantly, water cannot be currently recovered for reuse with evaporation ponds, making it difficult to have a circular water economy, especially for regions and industries with water resource challenges.

Owing to the excessive cost and energy consumption of ZLD, there are doubts on its practical viability and universal necessity. MLD has emerged as an alternative strategy for brine management14,15,16. However, we contend that MLD is not a third category of brine management in addition to ZLD and brine disposal. MLD cannot serve as a standalone approach for brine management as it results in a small volume of highly concentrated brine. Without the final step of BCr or evaporation pond, out-of-facility brine disposal approaches are still needed, such as deep-well injection and ocean discharge (Fig. 1). In other words, ZLD and brine disposal should remain as the two conceptual categories of brine management strategies. MLD is simply BVR plus disposal, which should still fall within the category of brine disposal. One scenario that is tricky for classification is when the concentrated brine is trucked to a distant evaporation pond. Although brine crystallization occurs in this case, as characteristic of a ZLD process, we tend to classify this scenario as MLD and disposal because the evaporation pond is not part of the onsite brine treatment facility.

In this sense, the choice between ZLD and MLD depends on the cost comparison between BCr or evaporation pond versus locally available brine disposal means. Unless ZLD is enforced by regulations or preferred to enable water reuse for sustainability goals, MLD is often more favourable. Because disposal and the final steps of ZLD are often costly, using cost-effective BVR is critical to reducing the overall cost of brine management regardless of whether ZLD or disposal is adopted.

There is no widely accepted quantitative definition of MLD. One possible definition is based on water recovery (WR), with a targeted WR of up to 95% (as opposed to nearly 100% for ZLD) often used in the literature14,16. However, defining MLD based on a fixed WR is arbitrary because the salinities and compositions of different feedwaters can vary markedly. For example, a WR of 80% can be easily achieved in RO desalination of brackish water with a TDS at 3 g l−1 (such as at a desalination plant in El Paso, TX, USA25), whereas such a WR is not possible for an RO process to concentrate produced water of TDS higher than 100 g l−1 from the Permian Basin, NM and TX (USA)26,27. In the context of managing RO desalination brines, using WR can also cause confusion as WR can be defined based on the raw feedwater (such as seawater or brackish groundwater) or the brine resulting from desalination.

Another potential approach to define MLD is based on the TDS of the brine for disposal, which is adopted by the current technology development of pursuing ultrahigh WR RO11,28,29. However, setting a standard TDS value to define MLD is also problematic. Specifically, brines with the same TDS but different chemical compositions can behave markedly differently, with some far below mineral saturation and others near or even beyond saturation before any concentrating step. Such a difference results in different potential of mineral scaling that limits the WR of desalination.

Industrial need and potential applications

The need of brine management varies among different industries. In this section, we discuss the motivations of five industries to pursue ZLD or MLD (Table 1). Particularly, we focus on how brine properties such as chemical composition and volume, as well as the treatment goal and regulations, affect the viability and prospects of ZLD and MLD.

Desalination

Desalination of seawater, brackish water and municipal wastewater has been used across the globe at full scale to supply fresh water for the coastal and inland regions, respectively. Owing to its cost-effectiveness and energy efficiency, RO is the state-of-the-art technology for both seawater and brackish water desalination12,30. The WR and the corresponding brine volume of RO are constrained by both the salinity limit and the risk of mineral scaling. Considering a typical TDS of 35 g l−1 for seawater and an RO brine salinity of 70 g l−1, the WR of seawater RO (SWRO) is optimized to be ~50%, which has been adopted by current seawater desalination plants12,31. Despite the controversy of its environmental consequences32,33,34, discharging SWRO brines into the ocean with minimal treatment is the business-as-usual practice for brine management owing to its low cost, and no major SWRO plant has publicly pursued ZLD. The use of MLD for SWRO brine management is also unlikely, as discharging a smaller volume of brine with higher salinity does not ameliorate the environmental concerns of ocean discharge. Therefore, it is difficult to envision stricter future regulations requiring managing the TDS of SWRO brine if ZLD remains cost prohibitive.

Compared with seawater desalination, ZLD and MLD are more necessary and practical for managing brines from municipal wastewater reuse, industrial wastewater and brackish water reverse osmosis (BWRO)7,35. Inland BWRO does not have the option of discharging its brine directly into the ocean. Current brine management practices, such as deep-well injection, evaporation pond and discharge to publicly owned treatment works or surface water, are either costly or infeasible owing to geological restrictions or economic, environmental and regulatory concerns7. As a result, wide adoption of inland desalination is hindered by the challenge of brine management7,8. As the salinities of brackish groundwater are typically between 1 g l−1 and 10 g l−1, the WR of BWRO can theoretically reach 85–98% before the brine osmotic pressure exceeds the working pressure upper bound of the existing RO processes. However, existing BWRO plants typically achieve WR between 60% and 85%25,36,37, generating a substantial volume of brine. Such a constraint on WR is a result of mineral scaling, rather than a limit owing to a large brine osmotic pressure. The precursors of sparingly soluble minerals (such as calcite, gypsum, barite and silica) are commonly rich in groundwater38,39 and are concentrated in BWRO as water is recovered, causing oversaturation of the minerals in the retentate downstream in the RO modules. The formation or deposition of minerals on the membrane surface is detrimental to RO by reducing the water permeate flux and membrane lifetime13,40. Developing effective scaling mitigation strategies can facilitate BVR, which will benefit both ZLD and disposal and thereby enhance the viability of inland desalination by BWRO.

Achieving ZLD or MLD can help existing BWRO plants expand their capacities of water production. For example, five major inland brackish desalination plants of Southern California discharge their brines via the Inland Empire Brine Line system of the Santa Ana watershed41. The allocated brine discharge capacities for different BWRO plants impose limits on the water production capacities of the respective BWRO plants for a given WR25. For BWRO plants that have already reached their allocated capacities, increasing WR (equivalent to attaining BVR) is the only option to increase their water production capacities. An increase of WR from 80% to 95%, for example, will translate to an expansion of water production capacity by fourfold assuming discharging brine at the same rate.

Oil and gas extraction

The production of oil and natural gas has greatly increased globally owing to the technology development of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. However, hydraulic fracturing requires substantial water consumption while generating a large volume of flowback and produced waters (FP water)42,43. Depending on the geological formation, FP water can be hypersaline with various hazardous contaminants such as hydrocarbons, radionuclides and other toxic chemicals26,44. Therefore, the management of FP water represents a major sustainability challenge in oil and gas-producing regions. Currently, the business-as-usual strategy of FP water management is deep-well injection45, a mature technology that has limited capacity and side effects of induced seismicity and groundwater contamination3,46,47. Moreover, many fracking sites are located in regions that are already stressed in water resource42. As a result, treatment and reuse of FP water has attracted rising interests as a solution to the dual challenge of water scarcity and pollution caused by the oil and gas industry26,48.

Although ZLD and MLD have been proposed for managing FP water, their practical implementation is hindered by regulatory and technoeconomic constraints. Owing to the hazardous nature of FP water, the fates of both treated product water and by-products of concentrated brine or salts need to meet regulatory requirements for reuse and disposal. Use of the treated product water from FP water has been suggested for various applications, such as discharge to surface water, livestock watering, irrigation and municipal usage3,49. However, there is a lack of explicit regulations regarding the use of treated FP water for most of these applications. For example, although reusing FP water has been shown to make a substantial volumetric impact on irrigation needs for several counties of Colorado (USA)50, reclaimed water allowed for irrigation in Colorado does not include industrial wastewater but is limited to secondary effluent from municipal wastewater treatment works3. Moreover, discharging treated produced water in the USA is allowed only for onshore oil and gas facilities west of the 98th meridian according to Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations Part 435 (40 CFR 435)49,51, and a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit needs to be issued49,51. However, acquiring NPDES permits is often time-consuming and the NPDES water standards have large geographical variations3. By contrast, solid waste generated from oil and gas production in the USA is subject to regulation under Subtitle D of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA)52. Although oil and gas solid wastes are enriched with toxic constituents that are more complex and hazardous than those of domestic solid wastes, the detailed regulations, costs as well as health and ecological risks of their disposal have not been extensively reported in the literature. Taking landfill as an example, relevant regulations often do not discuss oil and gas wastes specifically or define the type of landfill required for disposal53. This ambiguity casts more doubts on the feasibility of ZLD for FP water treatment.

Compared with the desalination industry, which supplies fresh water mainly for municipal use, some stakeholders in the oil and gas industry can likely afford higher costs (per volume) of wastewater treatment owing to the industry’s higher profitability. For example, the oil and gas companies at the Marcellus Basin, Pennsylvania can endure a reported cost of US$94–126 m−3 for deep-well injection owing to the long distance of transporting FP water to Ohio where injection wells are located54. Such high costs enable the application of a commercial ZLD treatment train for FP water reuse, which requires US$41–63 m−3 (ref. 49). This cost range is comparable to that reported by Tavakkoli et al. (approximately US$60 m−3, including the cost for the transportation of FP water and brine as well as brine disposal by injection)55, who estimated the expense of concentrating Marcellus Shale FP water from a salinity of 100 g l−1 to 300 g l−1 using membrane distillation (MD). However, such a scenario is unlikely applicable to all oil and gas-producing regions. In the Eagle Ford region of TX, USA, the cost of FP water disposal via deep-well injection is US$2–4 m−3 plus an average of US$6–9 m−3 for transportation54, rendering deep-well injection an economically competitive approach. Indeed, alternative recycling strategies such as internal reuse of FP water for hydraulic fracturing, which requires only moderate and less expensive treatment3, can be more economically viable than ZLD and MLD if new wells are drilled in close proximity to existing wells. Therefore, ZLD and MLD will be implemented by the oil and gas industry only if explicit regulations on treated FP water application and brine or salt disposal are in place, and other management approaches such as deep-well injection and internal reuse are either economically prohibitive or unavailable.

Power generation

The power industry, one of the largest water users, is another industry that generates high-salinity wastewater. Wastewaters from power plants include flue gas desulfurization wastewater and cooling tower blowdown, which have salinities typically ranging from 15 g l−1 to 80 g l−1 (refs. 56,57,58,59). The wastewater from power plants are contaminated by various pollutants, such as nutrients, salts (similar to sulfates) and heavy metals (including mercury, arsenic and selenium)2, resulting in strict regulations such as the Final Effluent Guidelines for steam electric power generation facilities published by US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2015 (ref. 60). According to this regulation, coal-fired power plants need to either implement chemical and biological treatments by 2018 or adopt ZLD for flue gas desulfurization wastewater management by 2023 (ref. 61). As a result, the power industry is one of the few industries that widely adopt the concept of ZLD at full scale in the USA. In an industrial survey of 82 ZLD facilities62, for example, more than 60 are from the power industry.

ZLD systems in the power industry have mainly applied MVC-based BC and BCr, which have been commercialized and installed in power plants nationwide in the USA2,63. Closed-circuit RO, an RO variant that enables high WR with low energy consumption64,65, has been also used by power plants in California to generate fresh water used by gas combustion turbines while reportedly generating a less volume of RO brines than a conventional RO system66. Compared with a traditional ZLD scheme that solely relies on BC and BCr, the ZLD system incorporating closed-circuit RO has the potential to reduce the levelized cost of water by 67%, based on a power plant in Denver, CO, USA as an example2. Such a substantial cost saving is mainly due to the remarkable reduction of energy consumption (by 90%) and capital investment (by 63%) by using RO for BVR. The same study also demonstrates that the implementation of ZLD can effectively reduce water withdrawals by the power industry2. Considering the existence of explicit regulations and concerns over water usage and scarcity, we envision that the power industry will maintain its role as a leading user in the ZLD market.

Semiconductor manufacturing

The rapid growth of semiconductor industry has led to an annual sale of more than one trillion semiconductors globally, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association67. However, semiconductor manufacturing is a water-intensive process, which requires large amounts of ultrapure water produced via RO and additional treatment while generating hazardous wastewater that cannot be directly discharged to the environment6,68. Similar to the oil and gas industry, the semiconductor industry also faces a dual challenge of water scarcity and pollution. According to a survey with 28 semiconductor manufacturers68, producing 1 cm2 of semiconductor product consumes an average of ~8 l of water in 2021, with the industry consuming ~6 × 108 m3 worldwide annually. However, semiconductor fabrication facilities (fabs) are often located in regions that suffer from water scarcity owing to economic, workforce, low humidity, geological stability and other factors. It has been estimated that 40% of existing facilities globally will encounter high or extremely high risks of water stress by 2030 (ref. 69). For example, Arizona, a US state experiencing extensive drought conditions, is a semiconductor manufacturing hub that has nine fabs. According to the World Economic Forum, each of these fabs can consume 10 million gallons of water daily, posing a threat to local water supplies unless efficient water reuse can be achieved70.

The salinities of semiconductor wastewater are reported to be in the magnitude of 0.1–10 g l−1 of TDS71,72,73,74, whereas the TDS in the circulating water of cooling tower can be up to 6 g l−1 (ref. 75). Semiconductor wastewater contains various contaminants such as fluoride76, tetramethylammonium hydroxide73,77 and perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS, >1,000 ng l−1 (ref. 78)). The presence of these contaminants leads to stringent regulations on wastewater discharge, motivating the semiconductor industry to shift its wastewater management paradigm towards ZLD. Particularly, PFAS is a group of emerging contaminants that have gathered tremendous attention owing to its high persistency, toxicity and potential of bioaccumulation79,80,81. The maximum contamination levels of several PFAS species in drinking water, which were published by the EPA in 2024, are in the magnitude of nanograms per litre (parts per trillion)82. Such an ultralow threshold, although currently being applied to drinking water only, suggests that wastewater discharge could become challenging for the semiconductor industry.

The concepts of MLD and ZLD have been implemented by the semiconductor industry83. One brine reduction facility treats the wastewater using a high efficiency RO process, which mitigates silica scaling and achieves a high WR by combining extensive pretreatment with high pH (>10) operating condition84. The concentrate of high efficiency RO discharges to lined brine ponds either directly or after further treatment by a BC83. The liquid waste in the brine ponds may be delivered to evaporation ponds to achieve ZLD83. Although RO can theoretically recover a majority of water from semiconductor wastewater if the technical limitations owing to membrane fouling and scaling can be addressed, research is still needed to better understand the chemical composition of treated water and solids owing to the low concentration threshold in environmental regulations for certain pollutants (such as PFAS). Additionally, despite the motivation to reduce the water footprint of the industry, whether wastewater reclamation can produce water with sufficiently high quality for chip manufacturing remains uncertain.

Mining industry

Mining is another industry that generates a large volume of brines with toxic components85,86,87,88,89,90. These brines often require proper treatments, including potentially ZLD, for discharge or reuse. On the basis of how they are generated, there are generally three major types of mining wastewater that are potentially subject to MLD or ZLD. The first is process water which results from the processes of crushing, sorting and mineral recovery. Originally extracted from freshwater sources, process water becomes highly contaminated as it receives various constituents from contacting the ores and from mineral processing (such as metals, cyanide, acids, ammonia and surfactants)91,92,93. Process water is often stored in a tailing storage facility in which fine waste rock particles settle, and the supernatant water is reused in the process94,95.

The second type of mining wastewater is contact water — meteoric water that comes into contact with the contaminated areas on the mine site and thus requires treatment before discharge. Contact water is often composed of metals, suspended solids and sulfates that require treatment. Contact water may also include acid mine drainage, which is typically an acidic solution generated from contact water seeping through sulfidic waste rock96,97. However, owing to the low flows, low pH and long contact time, the concentrations of metals and sulfates in acid mine drainage are often much higher than in the general contact water98,99. The third type of mining wastewater results from dewatering, which is the process of extracting water from deep surface mine pits or underground mines to prevent the active mining area from flooding100,101. This water has similar characteristics to contact water but is continuously generated (rather than seasonally generated) for mines operated below the groundwater level. Such water from dewatering usually contains elevated levels of hardness, alkalinity, metals and silica90,102.

The water quality requirements for onsite reuse and recycling are minimal. Constituents such as cyanide that may negatively affect ore processing are typically the only constituents requiring targeted treatment before reuse103. Most sites, even in arid regions, have a net positive water balance owing to the mining operations occurring at or below the groundwater table and because water reuse is not top priority. More often, the goal of water management is to discharge water offsite to maintain water balance104,105. Treating water to meet water quality requirement for discharge generates brines that might need MLD or ZLD106,107.

Mines permit typically requires segregated treatment of the mining wastewaters. Contact water and dewatering flows may be treated with a single system, whereas process water must be treated separately. The general treatment process to discharge mining wastewater consists of chemical and physical pretreatment (oxidation, coagulation, flocculation, settling and filtration) followed by RO when it is required to meet discharge limits107,108. RO brine presents a major challenge because disposal options are limited. Current practice for RO brine disposal is evaporation ponds, underground injection or even storing it perpetually in open pits or returning it to the feed source, which is not sustainable as constituents rejected by the RO will accumulate and eventually undermine the water reusability108. For instance, a common scenario is that mining wastewater with high sulfate concentration may be treated with RO to the point of gypsum (CaSO4 •2H2O) saturation (~10–15 g l−1 sulfate). If the RO brine, now high in TDS and saturated with sulfate, were returned to the feed source owing to a lack of brine disposal methods, sulfates will accumulate to the point that water is no longer treatable with the existing RO systems. From this point, the RO system is rendered obsolete owing to gypsum saturation. That is where ZLD is critical to long-term sustainability of mining operations8,87,107.

Current and emerging technologies

A widely adopted ZLD strategy is to use RO to reduce the brine volume to the greatest extent possible and then further concentrate the RO brine using evaporation pond or MVC-based BC and BCr. Technologies to decrease the cost and increase of the energy efficiency of MLD and ZLD are being pursued, including pushing the limit of RO and its variants to achieve a higher level of BVR and developing alternative processes for brine concentration and crystallization. This section discusses current and emerging technologies for ZLD and MLD (Table 2).

MVC and thermal crystallization

BC and BCr are core processes of ZLD. The state-of-the-art BC is based on MVC, a well-established evaporative technology that uses a compressor to produce compressed vapour at an elevated temperature18 (Fig. 2a). Such vapour condenses to form distilled water while releasing the latent heat to evaporate the influent feedwater. The working principle of BCr is like MVC, while the near-saturated brine flashes in a vapour chamber (the evaporation vessel) and automatic pressure filters or centrifuges are often applied for crystal collection19,109.

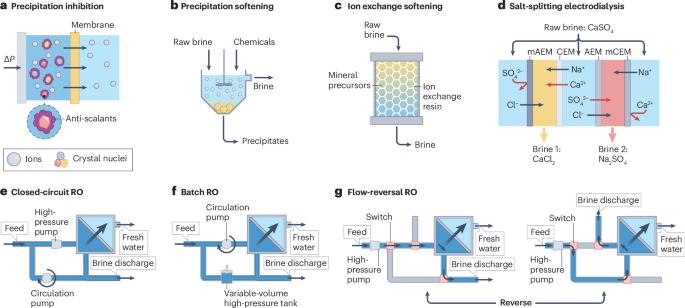

a, Mechanical vapour compression using a thermal evaporation mechanism but powered by electricity. b, Membrane distillation using low-grade heat to concentrate brine to near saturation. c, Electrodialytic crystallization using an electric field to remove ions from the feed and enrich them in a closed brine loop to induce crystallization. d, Solvent extraction desalination leveraging the dependence of water–solvent miscibility on environmental conditions (such as temperature and vapour pressure) to extract water from brine and to produce near pure water. e, Natural evaporation using evaporation pond or its variants with either light-adsorbing materials to enhance photothermal energy conversion or 3D structures to increase evaporation area. These systems are considered passive owing to the lack of electric components for separation or flow circulation. f, Convection-enhanced evaporation with two examples including wind-aided intensified vaporization (WAIV) and a water cannon. These processes are considered semi-active because they have electrical components that do not provide the primary driving force for separation.

MVC is generally considered as a cost-intensive and energy-intensive brine treatment process7, and extensive research has been performed to seek alternative technologies that potentially replace MVC in a ZLD treatment train. The perception of MVC being an energy-intensive treatment process is under the context when MVC is compared with all desalination processes, most of which cannot handle brines near saturation. As an evaporative brine treatment process, MVC is relatively efficient compared with available alternatives, and very few emerging technologies can currently outcompete MVC for ZLD. Specifically, MVC typically consumes 20–40 kWh of electricity to treat 1 m3 of brine7,110, which corresponds to a gain output ratio (GOR) of 10–20 if a WR of 65% is considered (for instance, concentrating a feedwater from TDS of 70–200 g l−1). Although MVC is substantially more energy-intensive than RO, MVC is indeed efficient as a thermal evaporative process, owing to its mechanism for highly effective recovery of latent heat released by vapour condensation111. For comparison, the GOR of MD, a hybrid thermal-membrane process extensively investigated for brine concentration (Fig. 2b), is practically less than 5 for a single-stage configuration111,112. In a direct contact MD process featured in Fig. 2b, a porous hydrophobic membrane separates the heated brine and the cold distillate and serves as medium for vapour transfer driven by partial pressure gradient113. MD has been touted for its capability of using low-grade thermal energy to desalinate hypersaline brine. Established thermal evaporative processes such as multieffect distillation and multistage flash distillation can achieve a similar GOR as MVC but only at a scale that is too large to be relevant to most brine treatment applications. Furthermore, thermal crystallizer requires electrical energy 50–60 kWh m−3 (ref. 7). As discussed subsequently, emerging technologies that enable brine crystallization do not yet show substantial energy savings.

One key limitation of MVC is the high capital cost because of the need to use expensive materials compatible with hot and saline brines18,19,20. For example, MVC uses heat exchangers made of corrosion-resistant titanium alloy, which costs 5–8 times more than brass, copper and nickel, which are used to make common heat exchangers used in less demanding conditions114. The prohibitively high capital cost of MVC is a main factor impeding its implementation in many small-scale brine treatment systems. Therefore, in addition to energy consumption, capital cost and operational robustness should also be key considerations when evaluating alternative active BCs and BCrs.

Emerging technologies and passive approaches

MVC and thermal crystallization are state-of-the-art and widely used in ZLD, but other approaches are being developed and tested. Electrodialytic crystallizers (EDCs), an electrodialysis (ED)-based technology, were developed to achieve non-evaporative brine concentration and crystallization115,116. The working principle of EDC is to use an electric field to drive ions to a closed loop with a stream constantly recirculated between the brine channels of the ED cell and an external crystallizer, forcing the salt concentration in the loop to exceed solubility and thereby inducing crystallization (Fig. 2c). Although EDC does not rely on evaporation to concentrate saline brine until salt crystallization, the energy consumption of EDC is estimated to range between 20 kWh m−3 and 30 kWh m−3 for the crystallization of Na2SO4 (ref. 115), which is at the same order of magnitude as MVC-based BC and BCr. Moreover, EDC with commercial ion exchange membranes is currently only applicable to brines with certain salts (such as sulfates)115,116. Specifically, for EDC to work well, the salts need to have low-to-moderate solubilities, and transmembrane water transport should be minimized115. For brines containing high level of chlorides, EDC either cannot achieve crystallization or consumes even more energy than MVC115. Therefore, despite its novelty and potential, EDC currently cannot replace MVC as a universally applicable crystallization process unless there is a breakthrough in process or membrane design to minimize the unintended transmembrane water transport.

Solvent extraction desalination (SED), or solvent-driven water extraction, is another process that has received extensive interest for brine concentration and crystallization. SED uses a low-polarity organic solvent that is partially miscible with water as the medium for water extraction117,118. A typical SED process comprises two distinct stages: the brine dewatering stage and the solvent regeneration stage (Fig. 2d). In the brine dewatering stage, the organic solvent is put into contact with the brine and extract part of the water, but not the ions, from the brine to form a water-–organic solvent mixture. This partitioning of water from the brine to the organic solvent can concentrate the brine up to saturation, forcing the formation of salt crystals119. In the solvent regeneration stage, a swing in condition is applied to promote the de-mixing of water and organic solvent, forming a biphasic mixture from which water can be readily harvested in a relatively pure form. The de-mixing can be stimulated by a swing in temperature120,121 or gas phase pressure122. Besides the difference in driving force, these two approaches also use solvents with very different characteristics. Specifically, solvents for temperature-swing-based SED have a higher specific capacity for water (per mass of solvent), whereas those for pressure-swing-based SED have a larger difference of volatility from water at room temperature119.

A similar approach (to SED) using organic solvent for brine crystallization is called solvent-driven fractional crystallization (SDFC)123. SDFC leverages the presence of a large mole fraction of organic solvent in an organic solvent-rich organic-aqueous solution to reduce the solubility of salts, thereby forcing the salts to precipitate out from the mixed solvent. The main differences between SED and SDFC are that SED forces precipitation by removing water from the aqueous solution, whereas SDFC forces precipitation by reducing salt solubility via changing solvent properties; and salts precipitate out in an aqueous solution in SED but in an organic solvent and water mixture in SDFC119.

SED has advantages and drawbacks. Electrically powered SED with swing in gas-phase pressure typically uses energy of ~50–100 kWh m−3, depending on the content of organic solvent in the product water122. Therefore, from an energy consumption perspective, SED has little-to-no advantage against MVC or other established thermal distillation processes. The main appeal of SED is the potential to minimize the deleterious effect of mineral scaling, possibly due to the mitigated precipitation at water–solid interfaces in SED processes in which precipitation tends to precipitate in the bulk water or the water–solvent interface. However, SED also faces the challenge of slowly losing solvent to the product water, which adds cost to replenishing the organic solvent and raises health concerns when using the recovered water119.

Low-grade waste heat utilization has been proposed to reduce the energy cost of brine concentration and crystallization with processes such as MD113, fibre-enhanced distillation124 and temperature-swing-based SED120. However, temporal and spatial disparities between waste heat availability and brine treatment demand cast uncertainties on the economic feasibility of waste heat-driven brine treatment125,126,127, because the costs associated with the collection, storage and transport of waste heat are often substantial. Despite the challenges of utilizing waste heat and the lack of advantage in energy efficiency over MVC, these alternative thermally driven processes could have merit (such as lower capital cost) because energy use is only one of the factors that dictate the selection and adoption of active BCs and BCrs (active systems refer to those that require thermal or electrical energy input for separation).

Passive and semi-active approaches can also be used for crystallization. Evaporation ponds are an option for passive crystallization in regions with low land cost and dry climate22. These ponds are often equipped with costly infrastructure such as lining and monitoring system as required by regulations24. However, enhanced evaporators using photothermal materials and/or high surface area 3D structures have the potential to substantially reduce the footprint of evaporation ponds and the corresponding infrastructure costs128,129,130 (Fig. 2e). Semi-active systems such as wind-aided intensified vaporization (WAIV) and water cannons rely mainly on natural driving forces to achieve dewatering and crystallization131,132 (Fig. 2f). By leveraging high specific area and natural convection, these semi-active processes, with minimal energy input for flow circulation or spray, can achieve a treatment throughput per system footprint (~60 l m−2 per day) more than ten times higher than that of conventional evaporation pond (~5.5 l m−2 per day)133. However, these semi-active brine treatment systems are climate-dependent and require mitigation of salt drift, which is an important environmental concern133.

Ultrahigh-water-recovery RO

Brine concentration and crystallization processes are costly and energy-intensive, and emerging technologies are currently unable to replace the state-of-the-art MVC and thermal crystallizer. Hence, maximizing BVR using RO is generally the most cost-effective approach for brine management, regardless of whether MLD or ZLD is implemented.

Depending on the source water characteristics, there are two major challenges in achieving an ultrahigh WR using RO. The first challenge is the very high brine TDS even at a moderate WR because the source water TDS is high (Fig. 3a). With high TDS, the osmotic pressure of the brine can far exceed the working pressure of commercially available RO systems. The second challenge is mineral scaling, which is the formation of mineral precipitates on membrane surfaces when the brine is oversaturated with barely soluble species such as gypsum, calcite, barite and silica13,40 (Fig. 3b). The formation of mineral scales on the membrane surface decreases the water permeate flux and lifetime of RO membranes13,40. Water from many sources do not necessarily face the first challenge as the TDSs of their brines after being concentrated by RO still fall within the working range of commercial RO systems. Comparatively, the second challenge is universal to most water sources and is thus the most common limiting factor for achieving ultrahigh WR using RO.

a, High total dissolved solids (TDSs) brine is a challenge to achieving a high water recovery (WR) in reverse osmosis (RO). The high TDS brine has a high osmotic pressure and thus requires a high applied pressure to push water through a semi-permeable membrane. The osmotic pressure of the retentate continues to increase as water is recovered, depleting the driving force and resulting in negligible flux after a low-to-moderate WR is achieved. b, Mineral scaling is also a challenge to achieve a high WR in RO. In this illustrated example, the maximum WR is not limited by a high brine TDS or osmotic pressure, as the flux drops precipitously even when there is a large driving force (the difference between applied pressure and retentate osmotic pressure). Instead, recovering more water concentrates all ions in the brine, including those that can form precipitates that decrease the performance of RO membranes. Three different technologies can address the challenge of high brine TDS. c, High-pressure RO (HPRO) applies a pressure (ΔP) that exceeds the osmotic pressure of the brine (πb). With an RO membrane, the brine osmotic pressure roughly equals the transmembrane osmotic pressure difference (Δπm). HPRO requires redesign of membranes and modules to withstand high operating pressure. d, Counter-flow RO (CFRO) uses a draw solution to reduce the transmembrane osmotic pressure difference. e, Low-salt-rejection RO (LSRRO) uses a leaky membrane to reduce the transmembrane osmotic pressure difference. Both CFRO and LSRRO enable water permeation using an applied pressure that is lower than the brine osmotic pressure (πb > ΔP > Δπm).

Addressing these two challenges to achieve ultrahigh-WR RO for BVR requires different technical approaches. For the challenge of high brine TDS, there are two categories of approaches that have been explored to enable RO for concentrating brine to a TDS of 250 g l−1. The first approach is the development of ultrahigh-pressure RO (UHPRO)11, which involves modifying the design of RO membranes and modules to withstand very high working pressure (up to 300 bar) (Fig. 3c). Key technical challenges for UHPRO include membrane compaction and factors that affect system integrity and reliability for working at an ultrahigh pressure134,135. Membrane compaction refers to the densification of the mesoporous polysulfone support layer under high pressure and leads to substantial (up to 50%134) reduction of water permeability. Besides membrane compaction, the implementation of UHPRO also requires redesign of several other key components of RO systems such as spacers, housing and energy recovery devices.

The second category of approaches to enable RO, or pressure-driven membrane processes in general, to concentrate high TDS brine is to reduce the transmembrane osmotic pressure difference via process innovation136. The basic principle underpinning this category of approaches is that water permeation occurs as long as the applied pressure exceeds the transmembrane osmotic pressure difference, even when the applied pressure is below the brine osmotic pressure. There are two major process designs that leverage this principle. The first process design is referred to as counter-flow RO (CFRO), which uses a draw solution on the other side of the RO membrane to reduce the transmembrane osmotic pressure difference (Fig. 3d). This type of RO shares mechanistic similarity with forward osmosis, except that the draw solution TDS is lower than the feed stream TDS in CFRO and that hydraulic pressure is applied in CFRO but not in forward osmosis. Various types of CFRO systems have configurational differences and include osmotically assisted RO137,138, cascading osmotically mediated RO139 and split-flow CFRO140. To achieve high-performance CFRO, it is expected that membranes for CFRO need to withstand a hydraulic pressure of at least 60–80 bar while having a membrane structure like that for forward osmosis membranes. Specifically, an ideal CFRO membrane should have a relatively thin support layer with ‘finger-like’ straight pores and high porosity, yielding a low structural parameter to minimize internal concentration polarization141,142. However, it is unclear that such support layers, which work well in pressure-free forward osmosis, can sustain the moderate pressure in CFRO.

The second process design that enables the transmembrane osmotic pressure difference to be substantially lower than the brine osmotic pressure is low-salt-rejection RO (LSRRO)16,143 (Fig. 3e). Except for the treatment goal, there is little difference between LSRRO and nanofiltration (a pressure-driven separation process using membranes with (sub)nanometre pores that are generally larger than those of RO membranes144) in both membrane and module design. An LSRRO membrane is essentially a ‘leaky’ membrane. Owing to the membrane ‘leakiness’ to salt, the transmembrane osmotic pressure difference can be substantially lower than the brine osmotic pressure, thus enabling water permeation even when the applied pressure is much lower than the brine osmotic pressure16. Compared with CFRO, LSRRO has the advantage of being compatible with commercially available membrane modules; CFRO requires module design for counter flows or membrane design for minimizing internal concentration polarization while withstanding a moderate pressure. In an experimental work, a three-stage LSRRO system with an operating pressure of 76 bar has been used to concentrate brine from 70 g l−1 to 225 g l−1 (of NaCl), achieving a WR of ~70% and a BVR factor of three145. In a pilot demonstration, LSRRO generated brines of >200 g l−1 TDS while producing high-quality permeate of 30–300 mg l−1 TDS146.

Theoretical investigation of LSRRO suggests a wide range of specific energy consumption (3–20 kWh m−3) for concentrating a model brine (NaCl) to >230 g l−1 (ref. 143). The value of the specific energy consumption depends on the feed (the unconcentrated brine) salinity, the number of stages and the applied pressure. Osmotically assisted RO was estimated to cost less energy (6 kWh m−3) to achieve a similar brine concentration, although the detrimental impact of internal concentration polarization was not considered in the analysis143. Another theoretical investigation using technoeconomic analysis suggests that the cost of LSSRO is comparable to that of CFRO (approximately US$2–15 m−3, depending on the starting TDS and WR)147.

Besides ultrahigh-TDS brines, there are various brines whose osmotic pressure is not exceedingly large and can be highly concentrated using commercially available RO systems with a moderate-to-high pressure (70–120 bar) if the challenge of mineral scaling can be addressed. Therefore, integrating pretreatment and/or interstage treatment unit processes for mineral scaling mitigation is the key to achieve ultrahigh WR using RO in this context. Compared with organic and biological fouling, mineral scaling involves more complex chemical reactions that lead to nucleation and growth of mineral salts. There are two mechanisms underlying mineral nucleation: crystallization and polymerization. A majority of mineral scales such as calcite, gypsum and barite are formed via crystallization processes13, whereas silica is generated by polymerization of silicic acid. This difference leads to variations in scaling behaviours and mitigation strategies among different scaling types148,149.

Current anti-scalants are designed to mitigate crystallization-induced scaling150 (Fig. 4a). However, there is a lack of commercial anti-scalants that are effective of controlling amorphous silica in membrane desalination150,151,152, making silica scaling an unaddressed problem that limits the RO from achieving an ultrahigh WR. Pretreatment of feedwater with precipitation softening or ion exchange softening can also remove scale precursors153,154,155 (Fig. 4b,c). However, pretreatment requires additional chemicals that increase the cost and environmental impacts of desalination. As a result, mineral scaling remains a major issue that constrains the cost efficiency and WR of current desalination systems.

a, Addition of anti-scalants to inhibit the formation of salt precipitates. b, Softening based on chemical precipitation of calcium and magnesium. c, Softening with ion exchange. d, Salt-splitting electrodialysis, which converts a brine with a high potential for gypsum (CaSO4•2H2O) scaling into two separate brine streams (CaCl2 and Na2SO4), each with a lower potential for scaling. e, Closed-circuit reverse osmosis (CCRO), which recirculates the concentrated brine and mixes it with raw brine for further water recovery. When the brine concentration in the loop becomes too high, the concentrated brine in the loop is discharged and the loop is filled with the raw brine for the next cycle of operation. f, Batch reverse osmosis (RO), in which the volume of the feed solution in the system is variable (whereas CCRO has a constant feed solution volume). Batch RO can also use alternative configurations with energy recovery devices. Both CCRO and batch RO decouple the water permeation flowrate and circulation flowrate, which enables the use of a high crossflow rate to mitigate the impact of fouling and mineral scaling. g, Flow-reversal RO, which alternates the flow direction of the feed stream to prevent the membrane near the exit of the module (in conventional RO) from constant exposure to the concentrated brine, which could cause fouling and scaling. ΔP, pressure; AEM, anion exchange membrane; CEM, cation exchange membrane; mAEM, monovalent-selective AEM; mCEM, monovalent-selective CEM.

Process innovations have been proposed to reduce mineral scalants in a chemical-free approach. For example, an variant of ED (namely, salt-free ED metathesis or salt-splitting ED) has been shown to enhance the WR of RO desalination by selectively removing scale precursors156,157,158. In salt-splitting ED, cationic and anionic scale precursors (such as Ca2+ and SO42− for gypsum) are separated from each other by transporting monovalent ions through a pair of ion exchange membranes (Fig. 4d). With this approach, the original brine with gypsum-forming precursors becomes streams with low scaling potential (such as CaCl2 and Na2SO4) that can be further concentrated by RO. Salt-splitting ED, therefore, can be used as a pretreatment or interstage treatment process to address gypsum scaling and facilitate RO for a high level of BVR.

Another strategy to reduce scaling is to use new variants of RO such as closed-circuit RO64,65 (Fig. 4e), batch RO159,160,161 (Fig. 4f) or flow-reversal RO162 (Fig. 4g). Both closed-circuit RO and batch RO were developed originally with the motivation to reduce energy consumption by achieving a more even driving force as the brine is concentrated159,160,162,163. For mitigating scaling potential, the key benefit with these RO configurations is the use of high crossflow rate to reduce the deposition of scalants and foulants at the membrane surface. This strategy is possible because the crossflow in these RO variants is decoupled from the permeation flow, unlike in conventional RO. Both the more evenly distributed driving force and the high crossflow rate can alleviate the detrimental impact of scaling and fouling. In flow-reversal RO, the direction of the feed stream is switched periodically to avoid having downstream membrane elements constantly exposed to high potentials of scaling and fouling. The effectiveness of these RO variants in scaling and fouling mitigation is an area of active research. However, even when proven effective, these RO variants will most likely be coupled with measures to mitigate scaling potential via adjusting water chemistry to provide a robust solution for scaling and fouling control that is essential for ultrahigh-WR RO.

Brine valorization potential

If valuable resources can be extracted from the brine left from ZLD and MLD using cost-effective approaches, the value generated from such extracted resource can offset the cost of these processes. Many types of the resources could potentially be extracted from brines, which are complex mixtures of ions164,165. For instance, extracting elements such as sodium, magnesium, calcium, lithium, rubidium, strontium, boron and gallium from the brines of more than 100 desalination plants in Spain could generate an estimated annual revenue between 13.4 and 29.8 billion euros166. However, for brine valorization to be economically feasible, it must generate products with qualities meeting the application requirements and value exceeding the cost of the valorization process itself. The cost of valorization also needs to account for the expense of transporting the valorized product to the end users, which renders the proximity of brine sources to corresponding consumers an important factor. Therefore, whether valorization adds value to brine management depends on technological, logistic and market factors, which need to be evaluated through technoeconomic assessment. Unfortunately, industrial data on the revenue of brine valorization are lacking. We briefly discuss several opportunities in which valorization could potentially add value to brine management, noting that we do not consider salt-lake and geothermal brines, which are sources of minerals but not considered as industrial waste streams that need to be managed.

One important class of resource that can be extracted from industrial brines is critical minerals. For example, FP water from certain geological formations contains lithium with concentrations that are sufficiently high for economically viable extraction167. The lithium ion (Li+) concentration and its ratios to the concentrations of coexisting ions such as Na+, Mg2+ and SO42− (which affect the difficulty to extract lithium) are comparable to salt-lake and geothermal brines26,167,168,169,170. Several processes can be used for lithium extraction, and the separation of Li from other cations is often the key (Fig. 5a). The selection of specific extraction process and treatment train design strongly depends on the brine composition.

a, Selective extraction of valuable constituents (such as lithium from produced water). b, Fractional crystallization to produce different salts. This method leverages the temperature-dependent solubility of different salts. c, Making acid and base from brine using bipolar membrane (BPM) electrodialysis. AEM, anion exchange membrane; CEM, cation exchange membrane.

Although detailed introduction to these processes is beyond the scope of this article, several important considerations for extracting lithium from produced water are highlighted. First, owing to the climatic conditions of the locations where FP water is generated, evaporation, which is commonly used as the first step to enrich lithium for extraction from salt-lake brines171, is not universally applicable for lithium extraction from FP water. Instead, direct lithium extraction (DLE) without evaporation step needs to be implemented172,173. Second, the choice of DLE technologies depends not only on the composition of the FP water but also on how the FP water is managed. ZLD and MLD already use a series of pretreatments and concentrate the lithium to a high degree. Therefore, the specific FP water (for DLE) is currently subject to deep-well injection, or ZLD and MLD have substantial impacts on the choice of the DLE technologies. For example, as a data point to show feasibility, extraction of 97% pure lithium carbonate from oil and natural gas brine in Marcellus Shale, Pennsylvania with up to 90% lithium recovery was reported174. The closed-loop process used involves combined physical and chemical treatment, concentration and crystallization.

Besides lithium, some FP water also contains substantial amount of rare-earth elements175,176, which are also critical minerals with the potential of adding value to brine management. In addition, other resources can be selectively extracted from FP water using integrated treatment trains, such as during pretreatment processes (such as softening). For example, during the pretreatment of FP water from the Permian Basin, ammonium, potassium and magnesium could be simultaneously recovered by struvite precipitation177. The precipitated struvite exhibited high purity and was free of heavy metals and organic contaminants, indicating a quality suitable for use as a fertilizer. The potential revenue of the recovered struvite precipitates as fertilizer was estimated to be US$4.92 m−3 FP water.

More generally (beyond FP water), another potential route of brine valorization is to produce high-purity salts via salt fractionation, which can be achieved by leveraging the different solubilities among salts at different temperatures (Fig. 5b). Salt fractionation has been reported in early 2000s when the concept was commercialized to recover salts such as precipitated calcium carbonate, gypsum magnesium hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide at the commercial grade from industrial wastewater62. In this process, lime or soda ash is added to the waste stream to precipitate these valuable salts owing to their much lower solubility than that of sodium salts. The salt products generated with this process in ZLD scenarios have been shown to generate net positive revenues62. As salt fractionation can be more economically favourable at larger scales, regional brine centres can be created to collect and process brines generated from distributed facilities to make fractional crystallization more viable.

Besides extracting valuable minerals as solids, other ways of valorizing the constituents in brines have also been explored actively. For example, the BWRO concentrate from a desalination plant in Texas will be converted to acid and base using bipolar membrane electrodialysis (BMED)25. BMED utilizes bipolar membranes to split water into H+ and OH− without electrolysis and pair the H+ and OH− with the anions and cations in the brine to produce acid and base, respectively (Fig. 5c). BMED is generally more energy-efficient than electrolytic acid–base generation and can also achieve additional desalination as part of the process. To sustain robust BMED performance, the brine often needs to be adequately softened to prevent scale formation178,179.

Another possible application of brines without separation and extraction of minerals is to use brine for cement production. For example, desalination brines have been explored to produce cementitious materials to reduce the carbon footprint of the cement industry180,181. In this case, the use of desalination brine not only reduces the water footprint of cement production but also provides the salts that can potentially enhance cement formation. Not requiring mineral separation and extraction gives this application an advantage over mineral extraction and recovery, despite the final product being lower in value than recovered critical minerals.

As mentioned earlier, the selection of the optimal valorization strategy needs to consider multiple factors such as technology readiness, cost of valorization as well as the value, market demand and consumer location of the valorization products. Additionally, certain valorization routes could present opportunities for synergy between valorization and ZLD or MLD. Brine valorization also offers environmental benefits by converting waste to valuable products, reducing the discharge of solids and liquid waste, lowering demands for mining and extraction and reducing carbon footprint of minerals production. Therefore, a unified framework based on the combined levelized cost of ZLD and MLD, valorization and environmental sustainability needs to be developed to facilitate the evaluation and optimization of brine management approaches.

Summary and perspectives

Brine management is critical to the sustainability of industries who produce large volumes of brine, including the desalination, energy, semiconductor and mining industries. ZLD has the potential to achieve complete WR in these industries, but MLD (which we categorize here as a type of brine disposal) is likely the more cost-effective solution in scenarios in which disposal options are available within a reasonable distance. Whether brines undergo ZLD, MLD or direct disposal is ultimately determined by economics and regulation. ZLD and MLD have been widely adopted in the energy and semiconductor industries but their use in other industries is more scenario-dependent. However, technological development, growing stresses on water resources and tightening regulations on brine disposal and water usage could promote wider ZLD and MLD adoption.

Technical innovations in brine crystallization technologies could have the potential to reduce the cost of ZLD and MLD. As the last step, brine crystallization or disposal is often the most expensive part in brine management, BVR advances will be key in cost reduction. In terms of improving energy efficiency and reducing cost, RO is one of the most promising approaches to improving BVR before crystallization or disposal. However, mineral scaling limits RO and must be addressed with better pretreatment and interstage treatment to reduce the scaling potential. Additionally, RO variants that provide a more uniform driving force and a higher crossflow rate can also help mitigate the detrimental impacts of mineral scaling. For high TDS brines, some RO variants that enable concentrating brines to a very high TDS also represent opportunities of developing cost-effective BVR processes.

Brine valorization has the potential to offset the cost of brine management or even make brine treatment profitable, but integrating valorization into ZLD and MLD in practice remains largely explorative. There are technical challenges associated with separation to obtain high-quality valorization products. The practical viability of valorization also hinges upon the ability to create valorization products with high enough value to justify the additional investment and the high enough demand within a reasonable distance from the brine treatment facility. Technoeconomic analysis can provide key insights into decision-making regarding whether to implement valorization, the type of valorization product and the choice of technologies.

There is no universally optimal approach for all brine management scenarios. The selection of technologies and engineering design for MLD and ZLD treatment trains can be treated as a constrained optimization problem, with technical and economic parameters and constraints that depend on location and regulations. Future research will be crucial in reshaping both technical and regulatory constraints, thereby influencing future treatment train designs. Technical limitations are likely to evolve as novel technologies emerge or existing methods are enhanced to enable more cost-effective brine concentration, crystallization and valorization. Understanding the economic factors and scalability of these technologies is vital for assessing their potential impact on advancing brine management practices. Additionally, the principles of industrial ecology can help identify location-specific opportunities — or limitations — for economically viable brine valorization pathways. Finally, developing a more comprehensive understanding of how brine disposal impacts surface and subsurface aquatic ecosystems, as well as local geological activity, will be essential for creating regulations that achieve a balance between environmental sustainability and economic feasibility.

Responses