Bugs in the system: the logic of insect farming research is flawed by unfounded assumptions

Introduction

The industrialised farming of insects for human food and animal feed has garnered “increasing attention from industry, policymakers and the scientific community”1. Insect farming has some characteristics that make it appear, at first glance, to be a sustainable option. For example, insects are more efficient at converting feed to protein than traditional livestock, and insects can consume a variety of feed sources2. Characteristics like these have powered a perception in the popular news press that insects may even be both a “superfood” and a “solution” to environmental challenges3.

While there are indeed characteristics that could potentially render insects more efficient under certain conditions, much of the academic research on insect agriculture tends to overlook the substantial challenges in developing a sustainable insect farming industry. The past couple of years have seen some warning signs emerge from the nascent insect industry—the growth of industrial insect farming has not kept pace with projections4, and there may be a declining appetite among investors for supporting new insect enterprises5.

While writing recent literature reviews on the potential contribution of insect farming to sustainability6,7,8, between August 2023 and March 2024, we surveyed research retrieved from Google Scholar, Scopus, OpenAlex and ScienceDirect using keywords like “insect farming/farm”, “environmental impact”, “Life Cycle Assessment/LCA”, “CO2/global warming/greenhouse gas”, as well as “black soldier fly”, “mealworm”, or “cricket”. In the process, we found that many studies labelled insects as sustainable while citing only a limited range of sources. As we discuss, some of these sources have been cited hundreds or thousands of times and continue to be heavily cited despite containing outdated or questionable assumptions. We also noticed that common assumptions which do not align with current industry practices continue to be employed. This issue appeared in studies directly assessing the contribution of insects to sustainability9,10,11, as well as those on nutritional aspects12,13, consumer acceptance14,15, or economic aspects16, and we discuss more examples in greater detail throughout this paper.

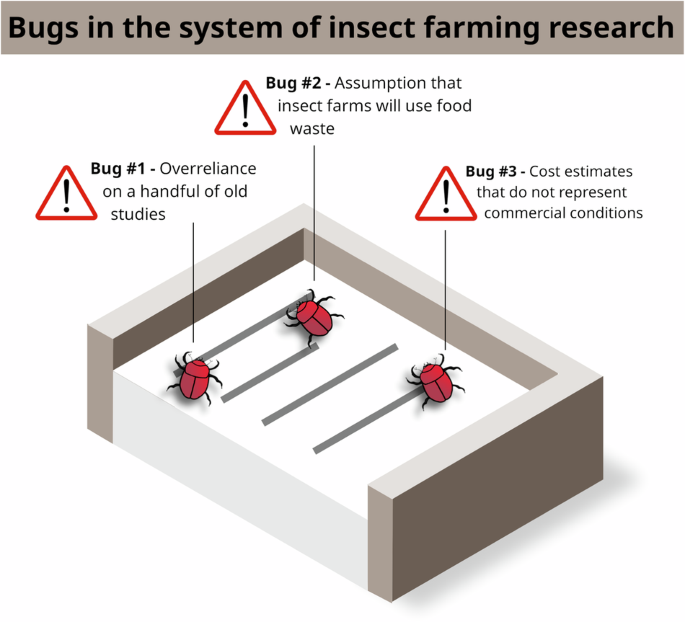

In this article, we offer one explanation as to why the promise of industrial insect agriculture may have been overstated. Specifically, we identify three bugs in the scientific literature on insect farming: (1) the overreliance on a handful of old studies when discussing environmental impacts; (2) the pervasive assumption that insect farms will utilise food waste; and (3) the reliance on theoretical price projections that do not hold up under commercial conditions. Figure 1 provides a visual overview of these bugs while Tables 1 and 2 expand on and summarize them.

Overview of the bugs in the insect farming research.

Bug #1: Overreliance on a handful of studies

When discussing the environmental sustainability of insect farming, a notable trend in the literature is the heavy reliance on a small number of older studies. While these studies were landmark contributions at the time, the insect industry has evolved to a point that these studies can no longer be considered representative of commercial-scale conditions.

The most frequently cited environmental studies on insect agriculture include Halloran et al.17, Smetana et al.18, and the widely influential 2013 FAO report2. This latter FAO report, which has amassed over 3000 citations, primarily bases its environmental impact data on a 2012 life-cycle analysis (LCA) by Oonincx and de Boer19. Oonincx and de Boer, one of the first LCAs in this domain, has itself garnered over 800 citations.

Typically, many papers in the field of insect agriculture start by highlighting the environmental harms caused by traditional meat production, followed by claims of insects being more sustainable with Oonincx and de Boer or the 2013 FAO report often serving as a primary citation. Despite the fact that Oonincx and de Boer are over a decade old, this pattern is followed even by very recent publications. For instance, Oonincx and de Boer underpins the graphs in van Huis11, is one of three studies referenced by Hadi and Brightwell20, and is the sole study regarding environmental impacts cited by van Huis and Gasco’s paper in Science21. This latter citation is particularly revealing, as van Huis and Gasco focus on using insects as feed for livestock while Oonincx and de Boer are explicitly concerned with insects as human food.

To illustrate how overreliance on outdated research may lead to excessively optimistic conclusions, consider the influential 2013 FAO report2. While this report was a useful contribution when it was written, its conclusions are nevertheless hindered by a range of limitations—many of which are shared widely by scientific studies on insect agriculture even today. First, the FAO report assumes that edible insects will directly compete with conventional meat; in reality, it appears more likely that insects will form ingredients for energy bars, biscuits, cookies, chips, crackers, protein powder, pasta, and bread—most of these have much lower environmental impacts than meat to begin with16,22,23,24. Second, the insects were fed a diet of carrots and mixed grains, such as wheat bran and oats, which could instead be used as human food or animal feed. Third, the report does not address the potential impacts of invasive species or pathogens. Fourth, water usage is not discussed, whereas recent studies have concluded that water usage by insect farms is high25. Fifth, the study was based on evidence from a small facility (83 tonnes per year), primarily selling live or frozen insects for birds or reptiles, which is very far from a large-scale facility producing insects for human consumption or animal feed. Sixth, the functional unit employed is one kilogram of fresh mealworms, excluding the considerable environmental impacts from the processing and drying steps26.

It is uncertain that the results of this study would scale. The industry requires quick development cycles for profitability, often achieved through high-quality feed. For example, the development cycles of yellow mealworms can be reduced to 26 days by using higher-quality feed, contrasting to the 70-day development cycle from the FAO report27. If a carrot-based diet results in slower growth, the processes and feeds used in this study may not accurately capture current industrial practices.

While the 2013 FAO report was a valuable step forward a decade ago, similar issues of excessive optimism are still prevalent in many recent papers. The fact that the 2013 FAO report is still widely cited suggests that this excessive optimism may be carried forward into the current literature on insect research. Also, the data limitations present when the 2013 FAO report was written have not yet been satisfactorily addressed. In Europe, for example, only four insect-related LCAs conducted on actual farms were available by 202128. Furthermore, the inherent variability of LCA results and their context-specific nature (varying by species, diet, geographical location, and production method) suggest that over-reliance on a single study can be misleading for understanding the general environmental impacts of insect farming29.

Bug #2: the assumption that insect farms will use food waste

The second bug in the literature on insect farming is the assumption that insect farms will utilise food waste at an industrial scale. To illustrate, several projections assume that insects could become cost-competitive and sustainable due to the extensive use of waste. These scenarios frequently contemplate the utilisation of up to 50% of the annual food waste from a given country. Examples of such scenarios have been produced by non-governmental organisations, such as the report by ADAS for the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in the UK10; industry bodies, such as the International Platform of Insects for Food and Feed30; governments, such as the European Commission31; the scientific community, as in the paper by Elleby et al.32; and investors, as in the Bryan, Garnier & Co report that which assumes 100% utilisation of food waste in the US and the EU33.

However, the premise that 50% or more of food waste will be used in insect farming is overly optimistic, given the substantial challenges in consistently acquiring such large quantities of waste6. The challenges include significant costs and infrastructural requirements for large-scale waste collection and necessary safety treatments; the fact that low-quality substrates (insect feed) can lead to slower growth rates and excess mortality, which may increase environmental impacts and compromise economic viability; variability of waste in terms of composition and availability, complicating the formulation of a consistent diet for animals; and potential competition for waste from other industries, such as biogas production or conventional livestock feed6,22,34. Moreover, such scenarios may assume that insect farming will incorporate food waste that is already allocated for use as feed for conventional livestock or even deemed inedible. The attributes rendering a substrate favourable for insect feed—such as cost, nutritional content, microbial safety, and stability of supply—commonly align with those that render it desirable for other applications.

It is important to note that insect farming faces barriers similar to those encountered when using food waste for livestock feed and anaerobic digestion, especially as substrates currently authorised for these industries are similar16. Even the countries that have been most successful at repurposing food waste for animal feed have only been able to utilise a minority of food waste and can only utilise some categories of food waste35,36.

Today, most insect farms exhibit little interest in using food waste, notwithstanding the authorisation of retail waste and food service waste in the United States. Clément Tiret, the CFO of leading company InnovaFeed, stated in an interview33: “The waste is a very interesting topic […] Although there is some great longer-term upside, it is extremely difficult to build an industry with a consistent quality product if your main input has a high level of variability.” Conversely, larger farms frequently choose grain-based substrates or agricultural by-products—the same ingredients that are already sought after as animal feed37.

Some studies on the environmental impact of insect agriculture do assume substrates that are closer to the industry’s current practices, such as grain-based products. Such studies indicate higher environmental impacts25,28,38.

Bug #3: the use of unsubstantiated cost estimates

The third bug in the logic of insect farming research is the use of unrepresentative cost estimates. Cost estimates based on actual operational insect farms tend to be much higher than those projected theoretically. Theoretical cost estimates can use incorrect parameters for dry matter contents, input costs, input requirements, and conversion factors between substrates and insects.

To illustrate, consider the cost estimates made in the ADAS study for the WWF in the UK10. In their “achievable” scenario, insects would feed on 54–82% of all available dairy, vegetable and bakery by-products and retail and manufacturing food surplus generated in the UK in 2050 (see online Supplementary Material for detailed calculations). This is despite several of these substrates being available as animal feedstock. The study undervalued the cost of some substrates, like bakery surplus, valued at £30–33/ton in the study but actually valued at $225 per ton in the US39. Equipment lifespans were assumed to be 30 years, significantly longer than the 5–20 years projected in other studies. Likewise, Suckling et al.‘s40 study of a modular container system in the UK overestimated bioconversion ratios. This study predicted larvae output per tonne of substrate to be five times higher than feasible. The mistake arose from using bioconversion rates suitable for dry brewer’s grains on wet brewer’s grains, without adjusting for the latter’s 20% dry matter content. And Pleissner and Smetana’s study41 of an industrial insect farm in Germany significantly underestimated electricity prices. The electricity prices in that study were lower than actual business electricity prices.

Over-optimistic cost estimates, in these studies and others, fail to represent the economic reality of running a financially sustainable insect business. Many insect startups struggle to scale and reach commercial production levels, with most winding down or going bankrupt within a few years, and the costs of production are a key reason42,43.

Towards the rigorous study of insect agriculture

The aim of this paper was to highlight the limitations in the existing literature that researchers should consider, along with the significant challenges associated with many commonly proposed scenarios. Our focus was on the research aspects, without delving into the business or economic implications these findings might entail. Consequently, this paper does not, in and of itself, provide definitive conclusions about the viability of the insect farming industry or the merits of investing in this sector. We do not take a stance here on whether other potential ways of enhancing the sustainability and economic viability of insect farming (e.g. integrating insect rearing into livestock farming rather than it functioning as a separate industry, or increasing experimentation) are promising.

The ‘why’ of these three bugs stems from a larger context in ways that may provide insight into issues besides insect farming. Initially, much of the motivation for insect farming centred around their potential as a food source. However, convincing consumers not only to try insects but also to regularly include them in their weekly shopping as a substitute for meat, has proven to be a significant challenge15,44. Introducing a novel ingredient into society is a complex process that involves much more than simply placing a new product on supermarket shelves; it needs to be part of a broader cultural experience45. Consequently, most investments have shifted towards using insects as animal feed46, steering insect farming away from areas where it might have had greater environmental benefits.

Even in communities with a tradition of insect consumption, insects are generally gathered from the wild in areas where they are naturally abundant and either consumed domestically or sold as a supplemental source of income47,48. In some cases, they are consumed primarily during periods when other foods are in short supply49. The mass rearing of insects by commercial enterprises attempting to scale on the model of other forms of contemporary intensive agriculture is, therefore, a new phenomenon. Although new technologies can offer environmental advantages under certain conditions, economic and other practical constraints frequently prevent these ideal scenarios from being realised. Achieving economic viability while maintaining sustainability, especially to the extent of replacing a substantial share of established products, is a difficult task.

Promising technologies often run against social and material limitations. Therefore, it is crucial for research to stay up-to-date and closely reflect actual industry practices. While theoretical promises may be enticing, researchers should prioritise understanding what the industry is genuinely doing. Although models can be valuable in specific contexts, they can sometimes overlook the challenges that arise in real-world situations.

How can the literature on insect agriculture be debugged? Firstly, the overreliance on a handful of environmental studies can be addressed by conducting new LCAs for the specific context of commercial-scale insect production in the Global North. Since LCAs are strongly context-dependent, such studies could pay close attention to the species being farmed, the environmental and economic conditions in the chosen country, and the end-use of the insect products (e.g. animal feed vs. human food). Secondly, studies can move beyond the unrealistic assumption that insect farms will utilise large volumes of food waste. Incorporating the current practices of industrial insect farms—such as the use of grain-based substrates—into LCAs would provide a higher, but more realistic, estimate of the environmental impact of insect farming25,28,38. Thirdly, cost estimates can be made more realistic by obtaining data from actual, commercial-scale operations. The financial details of individual insect farms are, naturally, kept confidential42. However, industry-wide surveys could provide aggregate estimates of the overall costs of production and the contribution of each cost component, which would enable more sober assessments of the economic viability of this industry.

The emerging insect industry has attracted a great deal of attention in the Global North. Our hope is that by identifying and addressing these three bugs, the scientific literature on industrialised insect agriculture can be made more robust. A more robust literature will be more effective in enabling society to make wise decisions based on rigorous economic and environmental studies as humanity moves towards a sustainable food system.

Responses