Bypassing the lattice BCS–BEC crossover in strongly correlated superconductors through multiorbital physics

Introduction

The collective and phase coherent condensation of electrons into bound Cooper pairs leads to the emergence of superconductivity. This macroscopic coherence enables dissipationless charge currents, perfect diamagnetism, fluxoid quantization, and technical applications1,2 ranging from electromagnets in particle accelerators to quantum computing hardware. Often, superconducting (SC) functionality is controlled by the critical surface spanned by critical magnetic fields, currents, and temperatures which a SC condensate can tolerate. Fundamentally, these are determined by the characteristic length scales of a superconductor – the London penetration depth, λL, and the coherence length, ξ0.

λL and ξ0 quantify different aspects of the SC condensate: The penetration depth is the length associated with the mass term that the vector potential gains through the Anderson-Higgs mechanism3. In consequence, magnetic fields decay exponentially over a distance λL inside a superconductor. Through this, λL is connected to the energy cost of order parameter (OP) phase variations and hence the SC stiffness Ds. The coherence length, on the other hand, is the intrinsic length scale of OP amplitude variations and is associated with the amplitude Higgs mode. ξ0 sets the scale below which amplitude and phase modes significantly couple such that spatial variations of the OP’s phase reduce its amplitude3,4.

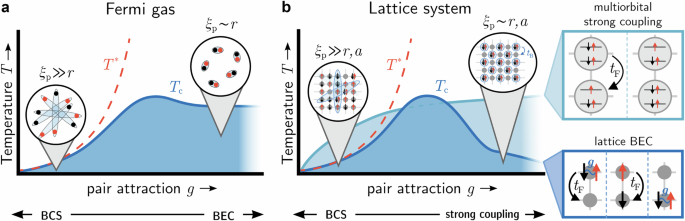

In addition to influencing the macroscopic properties of superconductors, λL and ξ0 play an important role to understand strongly correlated superconductors, as is epitomized in the Uemura plot5,6,7,8. For instance, the interplay of λL and ξ0 impacts critical temperatures9, it is relevant for the pseudogap formation10,11,12,13, it influences magneto-thermal transport properties like the Nernst effect8,14,15, and it might underlie the light-enhancement of superconductivity15,16,17,18,19. An important concept in this context is the BCS–BEC crossover phenomenology20,21,22,23,24. It continuously connects the two limiting cases of weak-coupling Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) superconductivity with weakly-bound and largely overlapping Cooper pairs to tightly-bound molecule-like pairs in the strong-coupling Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC) as the interaction strength or the density is varied (Fig. 1).

Evolution of the critical temperature Tc and Cooper pair size ξp in the BCS–BEC crossover (dark blue line) for (a) Fermi gases and (b) lattice systems. Both cases display a dome-shaped behavior of Tc in the intermediate crossover regime but behave qualitatively different in the strong coupling BEC phase: Tc remains finite in the Fermi gas (a)31 but approaches zero in the lattice case (b). During the crossover, ξp is reduced to the order of interparticle spacing r (a, b) and lattice constant a (b). For the lattice system, we contrast the evolution towards the multiorbital strong coupling phase (light blue line) discussed in this article. Here, the localization of pairs differently affects the bosonic hopping tB, as drawn in the insets on the right. In the lattice BEC limit, bosonic hopping relies on a second-order process involving two fermionic hoppings, tF, and a virtual intermediate state with broken pairs that is inhibited by the strong attraction g < 0. Consequently, this process and also ({T}_{{rm{c}}}propto {t}_{{rm{B}}}={t}_{{rm{F}}}^{2}/| g|) are quenched at large ∣g∣21,24. In the multiorbital strong coupling case, the local coexistence of paired and unpaired electrons fluctuating between different orbitals enables bosonic hopping tB as a first order process in tF without any intermediate broken pair states. See Supplementary Note 7 for details on the involved states and energy diagram specific to the case of A3C60. A second temperature scale T* is drawn in both panels as its splitting from Tc (corresponding to the opening of a pseudogap) marks the beginning of the crossover regime24.

The BCS–BEC crossover has been studied in ultracold Fermi gases23, low-density doped semiconductors25, and is under debate for several unconventional superconductors6,8,24,26,27,28,29,30. However, quasi-continuous systems, for instance Fermi gases, and strongly correlated superconducting solids show a crucially different behavior of how their SC properties, most importantly the critical temperature Tc, change towards the strong coupling BEC limit. While Tc converges to a constant temperature TBEC for Fermi gases in a continuum31 (Fig. 1a), Tc can become arbitrarily small in strongly correlated lattice systems due to the quenching of kinetic energy (Fig. 1b). Since the movement of electron pairs, i.e., bosonic hopping, necessitates intermediate fermionic hopping, it becomes increasingly unfavorable for strong attractions. Thus, as Cooper pairs become localized on the scale of the lattice constant, the condensate’s stiffness and hence Tc are compromised21,24. Figure 1 contrasts this generic BCS–BEC crossover picture for Fermi gases and correlated lattice systems in terms of the change of Tc and the pair size ξp as a function of pairing strength. Due to the decrease of Tc in the BCS and BEC limits, a prominent dome-shape of Tc can be expected in the crossover region for solid materials. Because of this, recent experimental efforts to increase Tc concentrate on stabilizing SC materials in this region24,25,27,30.

In this work, we demonstrate how multiorbital effects32,33 can enhance superconductivity beyond the expectations of the lattice BCS–BEC crossover phenomenology (as contrasted in Fig. 1b) with a model inspired by alkali-doped fullerides (A3C60 with A = K, Rb, Cs). The material family of A3C60 hosts exotic s-wave superconductivity of critical temperatures up to Tc = 38 K, being the highest temperatures among molecular superconductors34,35,36,37, and they possibly reach photo-induced SC at even higher temperatures15,17,18,38. In order to theoretically characterize the SC state, the knowledge of the intrinsic SC length scales is essential. While BCS theory and Eliashberg theory provide a microscopic description of λL and ξ0 for weakly correlated materials39,40,41, their validity is unclear for superconductors with strong electron correlations. To the best of our knowledge, ξ0 is generally not known from theory in strongly correlated materials. Only approaches to determine λL exist where an approximate, microscopic assessment of the SC stiffness from locally exact theories has been established, albeit neglecting vertex corrections42,43,44,45,46,47.

For this reason, we introduce a novel theoretical framework to microscopically access λL and ξ0 from the tolerance of SC pairing to spatial OP variations. Central to our approach are calculations in the superconducting state under a constraint of finite-momentum pairing (FMP). Via Nambu–Gor’kov Green functions we get direct access to the superconducting OP and the depairing current jdp which in turn yield ξ0 and λL. The FMP constraint is the SC analog to planar spin spirals applied to magnetic systems48,49,50. As in magnetism, a generalized Bloch theorem holds that allows us to consider FMP without supercells; see Supplementary Note 2 for a proof. As a result, our approach can be easily embedded in microscopic theories and ab initio approaches to tackle material-realistic calculations.

In this work, we implement FMP in Dynamical Mean-Field theory (DMFT)51 to treat strongly correlated superconductivity. In DMFT, the interacting many-body problem is solved by self-consistently mapping the lattice model onto a local impurity problem. By this, local correlations are treated exactly. We apply the FMP-constrained DMFT to A3C60 where we find ξ0 and λL in line with experiment for model parameter ranges derived from ab initio estimates, validating our approach. For enhanced pairing interaction, we then reveal a multiorbital strong coupling SC state with minimal ξ0 on the order of only 2 – 3 lattice constants, but with robust stiffness Ds and high Tc which increases with the pair interaction strength without a dome shape. This strong coupling SC state is distinct to the lattice BCS–BEC crossover phenomenology showing promising routes to optimize superconductors with higher critical temperatures. We discuss this possibility in-depth after the presentation of our results.

The remaining paper is organized as follows: First, we motivate how the FMP constraint is linked to λL and ξ0 from phenomenological Ginzburg–Landau theory after which we summarize the microscopic approach from Green function methods. Technical details are available in the Supplementary Information as cross-referenced at relevant points. Subsequently, we discuss our results for the multiorbital model of A3C60. Readers primarily interested in the analysis of these results might skip the first part on the physical motivation for obtaining superconducting length scales from the FMP constraint.

Results

Extracting superconducting length scales from the constraint of finite-momentum pairing

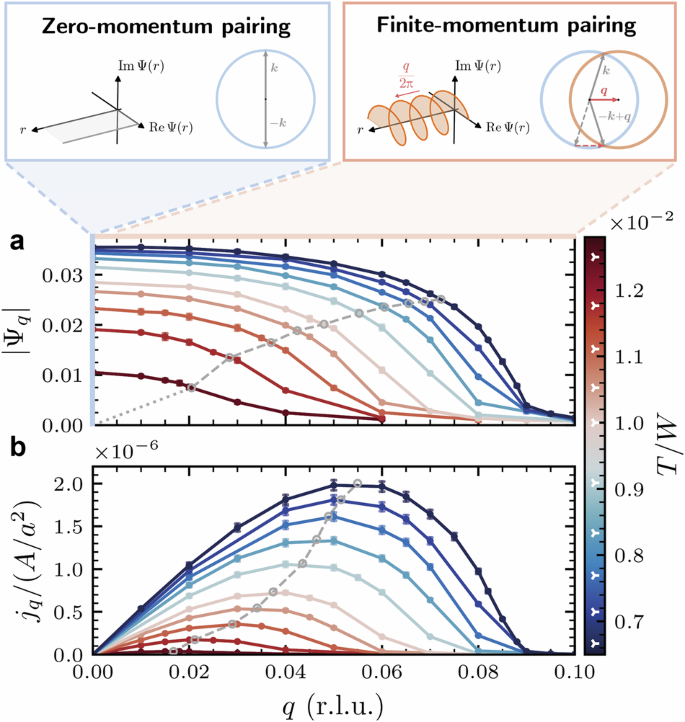

In most SC materials, Cooper pairs do not carry a finite center-of-mass momentum q = 0. Yet, in presence of external fields, coexisting magnetism, or even spontaneously SC states with FMP, i.e., q ≠ 0, might arise52,53,54,55,56 as originally conjectured in Fulde–Ferrel–Larkin–Ovchinnikov (FFLO) theory57,58,59. Here, we introduce a method to access the characteristic SC length scales ξ0 and λL of strongly correlated materials through the calculation of FMP states with a manually constrained pair center-of-mass momentum q4,40,60,61,62. For this, we enforce the OP to be of the FMP form Ψq(r) = ∣Ψq∣eiqr corresponding to FF-type pairing57, which is to be differentiated from pair density waves with amplitude modulations58,59,63. We contrast the OP for zero and finite momentum in real and momentum space in the top panel of Fig. 2. For FMP, the OP’s phase is a helix winding around the direction of q, while the OP for zero-momentum pairing is simply a constant.

The top panel insets sketch the position and momentum space representation of the order parameter (OP) Ψq(r) = ∣Ψq∣eiqr in the zero-momentum (left, q = 0) and finite-momentum pairing states (right, q > 0). The main panels show (a) the momentum dependence of the OP modulus and (b) the supercurrent density jq = ∣jq∣ as function of Cooper pair momentum q = ∣q∣ in reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.). Gray lines indicate the points of extracting ξ and jdp (see text). The data shown are results for the A3C60 model (c.f. Eq. (7)) with lattice constant a and interaction parameters U/W = 1.4, J/W = − 0.04 evaluated at different temperatures T (color coded; see color bar with white triangular markers).

Before turning to the implementation in microscopic approaches, we motivate how the FMP constraint relates to λL and ξ0. The Ginzburg–Landau (GL) framework provides an intuitive picture to this connection4,40,61 which we summarize here and discuss in detail in Supplementary Note 1, including a derivation of the following equations. The GL low-order expansion of the free energy density fGL in terms of the FMP-constrained OP reads

with q = ∣q∣. α, b, and m* are the material and temperature dependent GL parameters. Here, the temperature-dependent (GL) correlation length ξ(T) appears as the natural length scale of the amplitude mode (∝∣α∣) and the kinetic energy term

with its zero-temperature value ξ0 being the coherence length4. The stationary point of Eq. (1) shows that the q-dependent OP amplitude (leftvert {Psi }_{{boldsymbol{q}}}rightvert =leftvert {Psi }_{0}rightvert sqrt{1-{xi }^{2}{q}^{2}}) (T-dependence suppressed) decreases with increasing momentum q. For large enough q, SC order breaks down (i.e., Ψq → 0) as the kinetic energy from phase modulations becomes comparable to the gain in energy from pairing. The length scale associated with this breakdown is ξ(T) and can, therefore, be inferred from the q-dependent OP suppression. We employ, here, the criterion (xi (T)=1/(sqrt{2}| {boldsymbol{Q}}|)) with Q such that (| {Psi }_{{boldsymbol{Q}}}(T)/{Psi }_{0}(T)| =1/sqrt{2}) for fixed T (see Supplementary Note 5-A for more information).

The finite center-of-mass momentum of the Cooper pairs entails a charge supercurrent jq ∝ ∣Ψq∣2q, c.f. Eq. (8) in Supplementary Note 1. This current density is a non-monotonous function of q with a maximum called depairing current density jdp. It provides a theoretical upper bound to critical current densities, jc, measured in experiment. We note that careful design of SC samples is necessary for jc reaching jdp as its value crucially depends on sample geometry and defect densities40,61,64. As the current is related to the London penetration depth λL through the second London equation ({mu }_{0}{boldsymbol{j}}=-{lambda }_{{rm{L}}}^{-2}{boldsymbol{A}}), we can determine λL from jdp in GL theory via

with the magnetic flux quantum Φ0 = h/2e. The temperature dependence with the quartic power stated here is empirical39,40 and we find that it describes our calculations better than the linearized GL expectation as discussed in Supplementary Note 5-B. Note that taking the q → 0 limit in our approach is related to linear-response-based methods to calculate λL or, equivalently, the stiffness Ds47,62.

The GL analysis shows that the OP suppression and supercurrent induced by the FMP constraint connect to ξ0 and λL. In a microscopic description, we acquire the OP and supercurrent density from the Nambu–Gor’kov Green function

where ({psi }_{{boldsymbol{k}},{boldsymbol{q}}}^{dagger }=({c}_{{boldsymbol{k}}+frac{{boldsymbol{q}}}{2}uparrow }^{dagger },,{c}_{-{boldsymbol{k}}+frac{{boldsymbol{q}}}{2}downarrow })) (orbital indices suppressed) are Nambu spinors that carry an additional dependence on q due to the FMP constraint. G (F) denotes the normal (anomalous) Green function component for electrons (G) and holes ((bar{G})) in imaginary time τ. For s-wave superconductivity as in A3C6065,66,67,68, we use the orbital-diagonal, local anomalous Green function as the OP

which is the same for all orbitals α. This allows us to work with a single-component OP. The current density can be calculated via (c.f. Eq. (26) in the Supplementary Information)

where (hslash underline{{boldsymbol{v}}}={nabla }_{{boldsymbol{k}}}underline{h}({boldsymbol{k}})) is the group velocity obtained from the one-electron Hamiltonian (underline{h}({boldsymbol{k}})) and the trace runs over the orbital indices of (underline{{boldsymbol{v}}}) and ({underline{G}}_{{boldsymbol{q}}}). Underlined quantities indicate matrices in orbital space, Nk is the number of momentum points, and e is the elementary charge. See Methods and Supplementary Note 4 for details on the DMFT-based implementation and Supplementary Notes 3 for a derivation and discussion of Eq. (6).

The bottom panels of Fig. 2 show an example of our DMFT calculations which illustrates the q-dependence of the OP amplitude and current density for different temperatures T. Throughout the paper, we choose q parallel to a reciprocal lattice vector q = qb1. We find a monotonous suppression of the OP with increasing q. The supercurrent initially grows linearly with q, reaches its maximum jdp and then collapses upon further increase of q. Thus, both ∣Ψq∣ and jq behave qualitatively as expected from the GL description. For decreasing temperature, the point where the OP gets significantly suppressed moves towards larger momenta q (smaller length scales ξ(T)), while jdp(T) increases. We indicate the points where we extract ξ(T) and jdp(T) with gray circles connected by dashed lines.

Superconducting coherence in alkali-doped fullerides

We apply FMP superconductivity to study a degenerate three-orbital model H = Hkin + Hint, where Hkin is the kinetic energy and the electron-electron interaction is described by a local Kanamori–Hubbard interaction69

with total number (hat{N}), spin (hat{{boldsymbol{S}}}), and angular momentum operator (hat{{boldsymbol{L}}}). The independent interactions are the intraorbital Hubbard term U and Hund exchange J, as we use the SU(2) × SO(3) symmetric parametrization. This model is often discussed in the context of Hund’s metal physics relevant to, e.g., transition-metal oxides like ruthenates with partially filled t2g shells69,70. In the special case of negative exchange energy J < 0, it has been introduced to explain superconductivity in A3C60 materials65,66,67,68. In fullerides, exotic s-wave superconductivity exists in proximity to a Mott-insulating (MI)35,36,71 and a Jahn–Teller metallic phase36,72,73,74. The influence of strong correlation effects and inverted Hund’s coupling were shown to be essential for the SC pairing65,66,67,68,75 utilizing orbital fluctuations76 in a Suhl–Kondo mechanism72. In the weakly correlated regime of U → 0 and small J, the system follows BCS phenomenology66.

The inversion of J seems unusual from the standpoint of atomic physics, where it dictates the filling of atomic shells via Hund’s rules. In A3C60, a negative J is induced by the electronic system coupling to intramolecular Jahn–Teller phonon modes68,75,77,78. As a result, Hund’s rules are inverted such that states which minimize first spin S and then angular momentum L are energetically most favorable, see the second term of Eq. (7) for J < 0.

We connect the model to A3C60 by using an ab initio derived model for the kinetic energy79

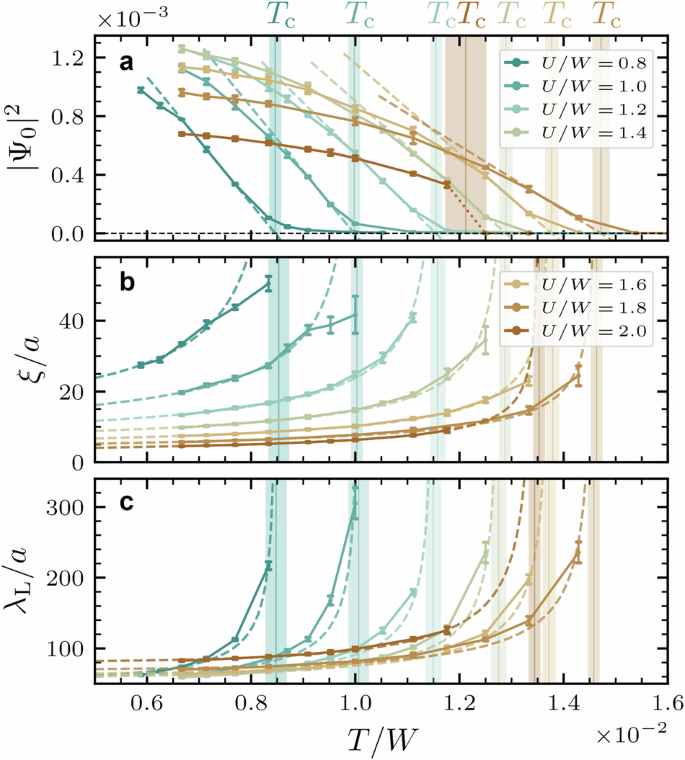

where tαγ(Rij) is the hopping amplitude between half-filled t1u orbitals (α, γ = 1, 2, 3) of C60 molecules on sites connected by lattice vector Rij. We take the bandwidth W as the unit of energy (W ≈ 0.3 – 0.5 eV for Cs to K based A3C60)68,79, see Supplemental Note 4-D for further details. For the interaction, we take the first principles’ estimates of fixed J/W = − 0.04 and varying U/W65,66,67,68,73 to emulate unit cell volumes as resulting from the size of different alkali dopants. We solve this Hamiltonian using DMFT, which explicitly takes into account superconducting order. Through the momentum dependence of ∣Ψq(T)∣ and jq(T), ξ(T) and λL(T) can be extracted as discussed in the previous subsection. We show the derived temperature dependence of ∣Ψq=0(T)∣, ξ(T), and λL(T) for different U/W in Fig. 3.

The temperature dependence of (a) the zero-momentum order parameter ∣Ψ0∣, (b) the correlation length ξ, and (c) the London penetration depth λL are shown for different ratios U/W. The data were obtained for fixed J/W = − 0.04 as estimated from ab initio data. Length scales are given in units of the lattice constant a. Fits to extract critical temperatures Tc and zero-temperature values ξ0 and λL,0 are shown by dashed lines. The region of uncertainty to fit Tc is indicated by shaded regions.

Close to the transition point, the OP vanishes and the critical temperature Tc can be extracted from ∣Ψ0(T)∣2 ∝ T − Tc. We find that Tc increases with U, contrary to the expectation that a repulsive interaction should be detrimental to electron pairing. This behavior is well understood in the picture of strongly correlated superconductivity: As the correlations quench the mobility of carriers, the effective pairing interaction ~ J/ZW increases due to a reduction of the quasiparticle weight Z65,66,67. The trend of increasing Tc is broken by a first-order SC to MI phase transition for critical U ~ 2 W which is indicated by a dotted line. Upon approaching the MI phase, the magnitude of ∣Ψ0∣ behaves in a dome-like shape. The Tc values of 0.8 – 1.4 × 10−2 W that we obtain from DMFT correspond to 49 – 85 K which is on the order of but quantitatively higher than the experimentally observed values. The reason for this is that we approximate the interaction to be instantaneous as well as that we neglect disorder effects and non-local correlations which reduce Tc67,68. The same effects could mitigate the dominance of the MI phase which prevents us from observing the experimental Tc -dome36,68.

Turning to the correlation length, we observe that, away from Tc, ξ(T) is strongly reduced to only a few lattice constants (a ~ 14.2 – 14.5 Å) by increasing U, i.e., pairing becomes very localized. At the same time, λL(T) is enlarged. Hence, the condensate becomes much softer as there is a reduction of the SC stiffness ({D}_{{rm{s}}}propto {lambda }_{{rm{L}}}^{-2}) upon increasing U. Fitting Eqs. (2) and (3) to our data, we obtain zero-temperature values of ξ0 = 3 – 10 nm and λL,0 = 80 – 120 nm. Comparing our results with experimental values of ξ0 ~ 2 – 4.5 nm and λL ~ 200 – 800 nm6,7,37,80,81, we see an almost quantitative match for ξ0 and a qualitative match for λL. Both experiment and theory consistently classify A3C60 as type II superconductors (λL ≫ ξ0)37,81.

We speculate that disorder and spontaneous orbital-symmetry breaking74 in the vicinity of the Mott state could lead to a further reduction of ξ0 as well as an increase of λL beyond what is found here for the pure system. This could bring our calculations with minimal ξ0 =3 nm closer to the experimental minimal coherence length of 2 nm revealed by measurements of large upper critical fields reaching up to a maximal Hc2 = 90 T in Ref. 80 using Hc2 = Φ0/(2πξ0) with the flux quant Φ0.

Circumvention of the lattice BCS–BEC crossover upon boosting inverted Hund’s coupling

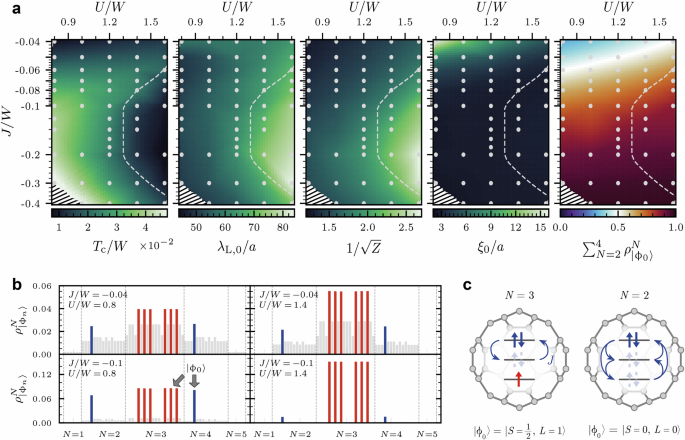

The inverted Hund’s coupling is crucial for superconductivity in A3C60. This premise motivates us to explore in Fig. 4 the nature of the SC state in the interaction (U, J) phase space for J < 0 beyond ab initio estimates.

a Critical temperature Tc, zero temperature penetration depth λL,0, inverse square root of quasiparticle weight Z, coherence length ξ0, and the statistical weight ({rho }_{leftvert {phi }_{0}rightrangle }^{N}) of the local lowest energy states (leftvert {phi }_{0}rightrangle) of the N = 2, 3, 4 particle sectors obeying inverted Hund’s rules as a function of U and J. Gray dots show original data points used for interpolation and the dashed line indicates a region where the proximity to the Mott state leads to a suppression of the superconducting state. There is no data point at the charge degeneracy line U = 2∣J∣ in the lower left corner as marked by black ‘canceling lines. b Distribution of statistical weights ({rho }_{leftvert {phi }_{n}rightrangle }^{N}) at four different interaction values U and J. (See Supplementary Note 7 for a listing of the eigenstates (leftvert {phi }_{n}rightrangle) and their respective local eigenenergies ({E}_{n}^{N})). Red (blue) bars denote the density matrix weight of ground states in the N = 3 (N = 2, 4) particle sector, the sum of which is plotted in the last panel of (a). c Exemplary depiction of representative lowest inverted Hund’s rule eigenstates. A delocalized doublon (electron pair) fluctuates between different orbitals due to correlated pair hopping J.

As long as ∣J∣ < U/2, we find that strengthening the negative Hund’s coupling enhances the SC critical temperature with an increase up to Tc ≈ 5 × 10−2 W, i.e., by a factor of seven compared to the ab initio motivated case of J/W = − 0.04. There is, however, a change in the role that U plays in the formation of superconductivity. While U was supportive for small magnitudes ∣J∣ ≲ 0.05 W, it increasingly becomes unfavorable for ∣J∣ > 0.05 W where Tc is reduced with increasing U. The effect is largest close to the MI phase where superconductivity is strongly suppressed. We indicate this proximity region by a dashed line (c.f. Supplementary Note 5-C).

The impact of U on the SC state can be understood from the U-dependence of the London penetration depth: λL grows monotonously with U and reaches its maximum close to the MI phase. Hence, the condensate is softest in the region where Mott physics is important and it becomes stiffer at smaller U. We find that this fits to the behavior of the effective bandwidth Weff = ZW ∝ Ds where the quasiparticle weight Z is suppressed upon approaching the Mott phase. The behavior of Z shown in Fig. 4a confirms the qualitative connection ({lambda }_{{rm{L}}}propto {D}_{{rm{s}}}^{-1/2}propto 1/sqrt{Z}) for ∣J∣ > 0.05 W. The J-dependence of λL is much weaker than the U-dependence, as can be seen in Fig. 4a and the corresponding line-cuts in Fig. 5.

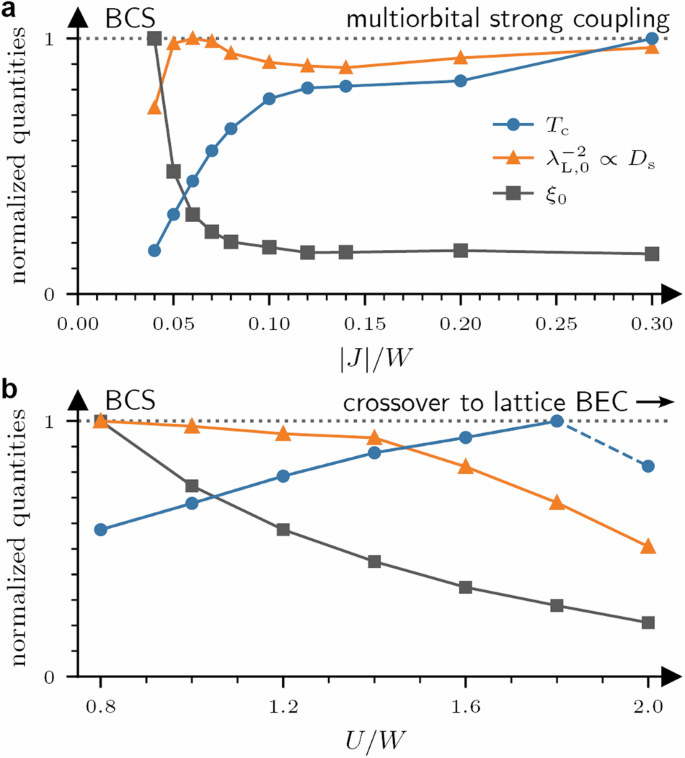

Critical temperature Tc, coherence length ξ0, and stiffness ({D}_{{rm{s}}}propto {lambda }_{{rm{L}},0}^{-2}) when approaching the multiorbital strong coupling state as function of ∣J∣/W at fixed U/W = 0.8 (a) and when approaching the Mott insulating state as function of U/W at fixed J/W = − 0.04 (b). To indicate a general trend, each quantity is normalized to its maximal value within the line cut. The phenomenology of the SC regimes resembles the BCS to lattice BEC crossover when approaching the Mott insulator (b), which is distinct from the multiorbital strong coupling case (a) (c.f. summary listed in Table 1). Note that the Tc at U/W = 2 in (b) corresponds to the transition from a Mott insulating state instead of a metallic phase, as visually differentiated by a dashed connecting line.

ξ0, in contrast, depends strongly on J. By just slightly increasing ∣J∣ above the ab initio estimate of ∣J∣, the SC state becomes strongly localized with a short coherence length on the order of 2 – 3 a. Remarkably, the small value of ξ0 is independent of U and thus the proximity to the MI phase. The localization of the condensate with ξ0 on the order of the lattice constant is reminiscent of a crossover to the BEC-type SC state. However, the dome-shaped behavior, characteristic of the lattice BCS–BEC crossover27,29, with decreasing Tc in the strong coupling limit is notably absent here. Instead, Tc still grows inside the plateau of minimal ξ0 when increasing the effective pairing strength proportional to ∣J∣ for fixed U/W (c.f. Fig. 5a). Only by diagonally traversing the (U, J) phase space, it is possible to suppress Tc inside the short ξ0 plateau with a dome structure as shown, e.g., in Ref. 73.

The reason for this circumvention of the lattice BCS–BEC phenomenology can be understood from an analysis of the local density matrix weights ({rho }_{leftvert {phi }_{n}rightrangle }), where (leftvert {phi }_{n}rightrangle) refers to the eigenstates of the local Hamiltonian of our DMFT auxiliary impurity problem. We show ({rho }_{leftvert {phi }_{n}rightrangle }) of four different points in the interaction phase space in Fig. 4b. In the region of short ξ0, the local density matrix is dominated by only eight states (red and blue bars) given by the “inverted Hund’s rule” ground states (leftvert {phi }_{0}rightrangle) of the charge sectors with N = 2, 3, 4 particles that are sketched in Fig. 4c. This can be seen in the last panel of Fig. 4a as the total weight of these eight states approaches one when entering the plateau of short ξ0.

By increasing ∣J∣, the system is driven into a strong coupling phase where local singlets are formed as Cooper pair precursors77 while electronic hopping is not inhibited. On the contrary, hopping between the N = 2, 3, 4 ground states is even facilitated via large negative J. It does so by affecting two different energy scales (c.f. Supplementary Note 7): Enhancing J < 0 reduces the atomic gap ({Delta }_{{rm{at}}}={E}_{0}^{N = 4}+{E}_{0}^{N = 2}-2{E}_{0}^{N = 3}=U-2| J|)69 relevant to charge excitations and thereby supports hopping. A higher negative Hund’s exchange simultaneously increases the energy ΔE = 2∣J∣ necessary to break up the orbital singlets within a fixed charge sector. As a result, unpaired electrons in the N = 3 state become more itinerant while the local Cooper pair binding strength increases. Since the hopping is not reduced, the SC stiffness is not compromised by larger ∣J∣. This two-faced role or Janus effect of negative Hund’s exchange, that localizes Cooper pairs but delocalizes electrons, can be understood as a competition of a Mott and a charge disproportionated insulator giving way for a mixed-valence metallic state in between82.

Correspondingly, as the superconducting state at −J/W > 0.05 relies on direct transitions between the local inverted Hund’s ground states from filling N = 3 to N = 2 and N = 4, the local Hubbard repulsion U has to fulfill two requirements for superconductivity with appreciable critical temperatures. First, significant occupation of the N = 2 and 4 states at half-filling requires that U is not too large. Otherwise, the system turns Mott insulating (around U/W ≳ 1.6 for enhanced ∣J∣) and the SC phase stiffness is reduced upon increasing U towards the Mott limit. At the same time, a significant amount of statistical weight of the N = 3 states demands that U must not be too small either. We find that Δat > 0 and thus U > 2∣J∣ is necessary for robust SC pairing. At Δat < 0 there is a predominance of N = 2 and 4 states, which couple kinetically only in second-order processes and which are susceptible to charge disproportionation82. Our analysis shows that a sweet spot for a robust SC state with high phase stiffness and large Tc exists for ∣J∣ approaching U/2.

Discussion

We summarize the overall change from a weak-coupling BCS state to the multiorbital strong coupling SC state characterized by Tc, ξ0, and ({D}_{{rm{s}}}propto {lambda }_{{rm{L}}}^{-2}) upon enhancing ∣J∣ in Fig. 5a and contrast it with the lattice BCS–BEC phenomenology in Table 1. Behavior as in the lattice BCS–BEC crossover can be found upon approaching the MI state (Fig. 5b), where strong local repulsion U decreases ξ0 and superconductivity compromises stiffness. As discussed above, we cannot observe a proper Tc dome that is seen in the experimental phase diagram due to the MI state dominating over the SC state in our calculations for fixed J/W = − 0.0436,67,68. However, an additional analysis of the SC gap Δ and coupling strength in Supplementary Note 6 indicates that our calculations are indeed in the vicinity of the crossover region. Diagonally traversing the (U, J) interaction plane by increasing U for J = − γU (γ ≤ 0.5) leads to a similar conclusion, although a Tc dome can emerge more easily73 as charge excitations controlled by Δat are suppressed at a slower pace.

Thus, two distinct localized SC states exist in the multiorbital model A3C60 – one facilitated by local Hubbard repulsion U and the other by enhanced inverted Hund’s coupling ∣J∣. One might speculate under which conditions THz driving or more generally photoexcitation15,17,18,38 could enhance ∣J∣ and steer A3C60 into this high-Tc and short-ξ0 strong coupling region, e.g., via quasiparticle trapping or displacesive meta-stability83. Further experimental characterization via observables susceptible to changes in ξ0 and λL, like critical fields, currents (see Supplementary Note 1-B), or thermoelectric and thermal transport coefficients8,14, can lash down the possibility of this scenario. Twisted bilayer graphene might be another platform to host the mechanism proposed in this work as an inverted Hund’s pairing similar to that in A3C60 is currently under discussion84,85,86.

On general grounds, the bypassing of the usual lattice BCS–BEC scenario via multiorbital physics is promising for optimization of superconducting materials to achieve higher critical currents or temperatures. Generally, limits of accessible Tc are unknown with so far only a rigorous boundary existing for two-dimensional (2D) systems87,88. An empirical upper bound to Tc emerges from the Uemura classification5,6,7,8 which compares Tc to the Fermi temperature TF = EF/kB ∝ Ds: the temperature ({T}_{{rm{BEC}}}^{3{rm{D}}}={T}_{{rm{F}}}/4.6) of a three-dimensional (3D) non-interacting BEC. Most superconducting materials, including cuprate materials with the highest known Tc at ambient conditions, however, are not even close to this boundary; typically, Tc/TBEC = 0.1 – 0.2 for unconventional superconductors. Notable exceptions are monolayer FeSe89 (Tc/TBEC = 0.43), twisted graphitic systems26,84 (Tc/TBEC ~ 0.37 – 0.57), and 2D semiconductors at low carrier densities25 (Tc/TBEC ~ 0.36 – 0.56) which all reach close to the 2D boundary ({T}_{{rm{c,lim}}}^{2{rm{D}}}/{T}_{{rm{BEC}}}^{3{rm{D}}}approx 0.575)87. Only ultracold Fermi gases can be tuned very close to the optimal TBEC23,24.

The empirical limitations of Tc in most unconventional superconductors with rather high densities make sense from the standpoint and constraints of the lattice BCS–BEC crossover. In this picture, high densities seem favorable for reaching high Tc as electrons can reach high intrinsic energy scales. Yet, lattice effects and their negative impact on the kinetic energy of superconducting carriers become also more pronounced, preventing Tc to reach TBEC. Possible routes to evade these constraints include quantum geometric and hybridization related band structure effects90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98 as well as the multiorbital Hund’s interaction effects triggering substantial localized stiffness uncovered here.

We emphasize that the framework to calculate the coherence length ξ0 and the London penetration depth λL introduced in this work can be implemented in any Green function or density functional based approach to superconductivity without significant increase of the numerical complexity. Thus, our work opens the gate for “in silico” superconducting materials’ optimization targeting not only Tc but also ξ0 and λL. On a more fundamental level, availability of ξ0 and λL rather than Tc alone can provide more constraints on possible pairing mechanisms through more rigorous theory-experiment comparisons, particularly in the domain of superconductors with strong electronic correlations.

Methods

Dynamical mean-field theory under the constraint of finite-momentum pairing

We study the multiorbital interacting model Hkin + Hint of A3C60 using Dynamical Mean-Field theory (DMFT) in Nambu space under the constraint of finite-momentum pairing (FMP). In DMFT, the lattice model is mapped onto a single Anderson impurity problem with a self-consistent electronic bath that can be solved numerically exactly. The self-energy becomes purely local Σij(iωn) = δijΣ(iωn) capturing all local correlation effects. To this end, we have to solve the following set of self-consistent equations

in DMFT51. Here, the local Green function Gloc is obtained from the lattice Green function Gk (first line) in order to construct the impurity problem by calculating the Weiss field GW (second line). Solving the impurity problem yields the impurity Green function Gimp from which the self-energy Σ is derived (third line). Underlined quantities denote matrices with respect to orbital indices (α), ({mathbb{1}}) is the unit matrix in orbital space, ωn = (2n + 1)πT denote Matsubara frequencies, ({h}_{alpha gamma }({boldsymbol{k}})={sum }_{j}{t}_{alpha gamma }({{boldsymbol{R}}}_{j}){{rm{e}}}^{i{boldsymbol{k}}{{boldsymbol{R}}}_{j}}) is the Fourier transform of the hopping matrix in Eq. (8), μ indicates the chemical potential, and Nk is the number of k-points in the momentum mesh. Convergence of the self-consistency problem is reached when the equality ({underline{G}}_{{rm{loc}}}(i{omega }_{n})={underline{G}}_{{rm{imp}}}(i{omega }_{n})) holds.

We can study superconductivity directly in the symmetry-broken phase by extending the formalism to Nambu–Gor’kov space. The Nambu–Gor’kov function under the constraint of FMP (c.f. Eq. (4)) on Matsubara frequencies

then takes the place of the lattice Green function ({underline{G}}_{{boldsymbol{k}}}(i{omega }_{n})mapsto {underline{{mathcal{G}}}}_{{boldsymbol{q}}}(i{omega }_{n},{boldsymbol{k}})) in the self-consistency cycle in Eq. (9). In addition to the normal component ΣN ≡ Σ, the self-energy gains an anomalous matrix element ΣAN for which the gauge is chosen such that it is real-valued.

We use a 35 × 35 × 35 k-mesh and 43200 Matsubara frequencies to set up the lattice Green function in the DMFT loop. In order to solve the local impurity problem, we use a continuous-time quantum Monte Carlo (CT-QMC) solver99 based on the strong coupling expansion in the hybridization function (CT-HYB)100. Details on the implementation can be found in Refs. 67,68. Depending on calculation parameters (T, U, J) and proximity to the superconducting transition, we perform between 2.4 × 106 up to 19.2 × 106 Monte Carlo sweeps and use a Legendre expansion with 50 up to 80 basis functions. Some calculations very close to the onset of the superconducting phase transition (depending on T or q) needed >200 DMFT iterations until convergence. We average 10 or more converged DMFT iterations and calculate the mean value and standard deviation in order to estimate the uncertainty of the order parameter originating from the statistical noise of the QMC simulation.

Further details on code implementation are given in Supplementary Note 4. It entails a comparison of finite-momentum pairing to the zero-momentum case51 in the Nambu–Gor’kov formalism, an explanation on the readjustment of the chemical potential μ to fix the electron filling, and a simplification of the Matsubara sum for calculating jq in Eq. (6).

Responses