Cardiac bridging integrator 1 gene therapy rescues chronic non-ischemic heart failure in minipigs

Introduction

Heart failure (HF), a clinical syndrome resulting from structural and functional impairment of cardiac filling and/or ejection of blood, has become a global public health burden affecting more than 64 million people worldwide1. Despite the high mortality and morbidity caused by HF, the mainstream therapeutic options for HF patients are still mainly limited to lifestyle management, systemic neurohormonal interventions, and mechanical assisted device or heart transplant2,3. Conventional pharmacological interventions are strategized to alleviate cardiac stress and systemic congestion with the pathogenic remodeling of failing heart muscle itself rarely addressed. Despite HF being a syndrome of failing heart muscle, there remains a significant unmet clinical need of myocardium focused therapeutic approaches for HF patients4. In recent years, gene therapy has emerged as a modality to deliver or modify target genes directly benefiting failing heart muscle3,5. Using targets that focus on individual proteins of the calcium handling machinery, the results of existing studies of gene therapy for HF treatment have not been convincingly positive5,6. It is possible that an upstream regulator of cellular architecture, which organizes multiple components of the calcium handling machinery, can be a potent target in reversing failing heart muscle.

A promising target for HF gene therapy development is cardiac bridging integrator 1 (cBIN1), a cardiomyocyte membrane scaffolding protein which sculpts transverse-tubule (t-tubule) microfolds to form functional calcium handling microdomains7. T-tubule cBIN1-microdomains not only attract and house L-type calcium channels (LTCCs) but also recruit ryanodine receptors and sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) juxtaposed at the opposing junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (jSR) membrane for a localized and coordinated regulation7,8,9,10. Its multilayered roles in calcium regulation position cBIN1-microdomains as an intracellular central platform and a master regulator of beat-to-beat calcium transients essential to excitation-contraction (EC) coupling in cardiomyocytes. Importantly, in failing cardiomyocytes from multiple models of acquired HF including human and mouse models, cBIN1 is transcriptionally reduced. The result of decreased cBIN1 is disruption of microdomain membrane at t-tubules, weakening calcium transients and impairing cardiac function10,11,12,13. Recent studies identified that disruption of t-tubule microdomains in failing cardiomyocytes can be restored by adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9)-transduced exogenous cBIN1 to rescue intracellular architecture, calcium cycling, and cardiac function in mouse models of HF10,13,14. The efficacy of AAV9-cBIN1 gene therapy remains to be tested in large animal models of HF.

Experimental large animal models of chronic rapid cardiac pacing-induced HF are characterized by classic features of HFrEF including LV chamber dilation and wall thinning, calcium dysregulation, and systemic neurohormonal alterations15,16,17. In this study, we explored the efficacy and safety of AAV9-cBIN1 gene therapy in a swine model of tachypacing-induced non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)18,19,20. Here we found that in minipigs with tachypacing-induced non-ischemic HFrEF, exogenous cBIN1 transduced by AAV9 effectively restores t-tubule microdomains and rescues cardiac function with improved survival, providing strong preclinical evidence in support of the promise of AAV9-cBIN1 as a therapy for patients with HFrEF not just to limit the deterioration of failing heart muscle but reverse failing heart muscle, restoring cardiac function.

Results

Myocardial cBIN1 reduction marks disease severity in patients with DCM and HFrEF

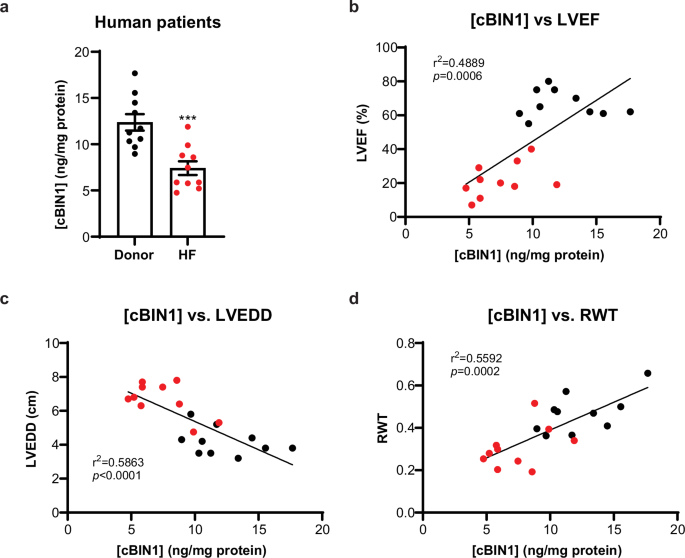

Previous studies indicate that cardiomyocyte transcription and protein expression of BIN1 are reduced in animal and human hearts with HF9,10,13,14,21. In this study, we used a standardized cBIN1-specific ELISA test11,12,21 to quantify myocardial cBIN1 protein levels in the left ventricular (LV) free wall tissue samples obtained from HFrEF patients for correlational analysis with LV remodeling and contractile dysfunction. Myocardial cBIN1 concentration, [cBIN1], in LV free wall samples from the HFrEF patients (LVEF ≤ 40%) is significantly decreased from that seen in non-HF donors (LVEF ≥ 55%) (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, myocardial [cBIN1] correlates positively with LVEF and relative wall thickness (RWT) while negatively (inversely) with LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) (Fig. 1b–d). These data are independent of medication and clinical history, suggesting that [cBIN1] is an accurate reflection of the pathologic remodeling that occurs in DCM progression. Prior studies in mice indicate that cBIN1 is causative of pathologic cardiac remodeling10,13,14. The human data in Fig. 1 are correlative, but given the tight correlation between [cBIN1] and LVEDD, these data indicate that low [cBIN1] may in fact cause ventricular remodeling in large animals and humans.

a Myocardial cBIN1 levels in LV free wall samples are quantified using cBIN1 ELISA kit and normalized to total protein levels ([cBIN1]) in HF patients and non-HF donors (n = 10 per group). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Unpaired Student’s t-test is used for two group comparison. *** indicates p < 0.001 for comparison vs. non-HF Donor. b–d Correlations between myocardial [cBIN1] and echocardiography measured left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (b), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) (c), and relative wall thickness (RWT) (d) in non-HF donors (black circles) and HF patients (red circles). Person’s correlation test was used for correlational analysis, followed by linear regression analysis.

AAV9-cBIN1 improves survival in minipigs with chronic non-ischemic HFrEF

In mouse models, we recently identified that exogenous cBIN1 introduced by AAV9 gene therapy can normalize reduced myocardial cBIN1 in failing cardiomyocytes, rescuing HF10,13,14. The current data from human HFrEF hearts (Fig. 1) further indicate that cBIN1 gene therapy has translational potential in humans. In preparation for such studies, here we tested the therapeutic efficacy of cBIN1 gene therapy in a large animal preclinical model of HFrEF.

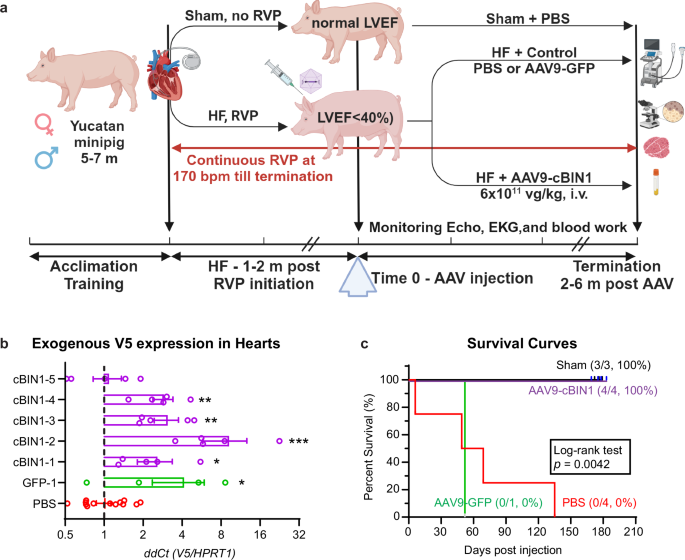

We used a minipig model of non-ischemic DCM and chronic HFrEF induced by continuous rapid ventricular pacing (RVP) via an implanted pacemaker and a pacemaker lead secured to the right ventricular apex18,19. As illustrated in the schematic (Fig. 2a), young adult (5–7 months of age) Yucatan minipigs (n = 10) were subjected to continuous RVP at 170 bpm. After an average of 7.7 ± 0.9 weeks of continuous RVP, all paced animals successfully developed DCM (LVEDV, 73.1 ± 5.8 vs. baseline 49.1 ± 2.4 mL, p < 0.05) and HFrEF (LVEF, 35.8 ± 1.9 vs. baseline 70.7 ± 1.8%, p < 0.001), with criteria being an LVEF ≤ 40% for two consecutive weeks. Once the animals met the criteria, each minipig was randomized to receive either a single intravenous dose of AAV9-cBIN1 (6 × 1011 vg/kg, IV) as the therapy group (n = 5) or control treatment with either vehicle PBS (n = 4) or a non-biological active virus AAV9-GFP (6 × 1011 vg/kg, IV, n = 1). The dose of AAV9-cBIN1 used here was based on our previous studies in mice10,13 and minipigs10 with established evidence of myocardial transduction lasting for 6 months in minipig hearts10. RVP was continued throughout the study period. Three additional minipigs underwent the same pacemaker implantation procedure without RVP initiation. These three animals were the healthy sham group. All minipigs were monitored with echocardiography, electrocardiography, bloodwork, and physical examination every 1–2 weeks until they reached the protocol-designated termination endpoint (6-month post-treatment) or met ethics committee-mandated euthanasia criteria due to severe congestive HF symptoms.

a Schematic illustration of experimental protocol (Created with BioRender.com). b Exogenous V5-labled transgene expression (RT-qPCR detected V5/HPRT1 and expressed as ΔΔCt when compared to PBS controls) in minipig left ventricular myocardium at termination (n = 5 sites across left ventricle in each pig). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Kruskal-Wallis test is used for comparison to PBS group (15 samples from 3 PBS-treated animals). *, **, *** indicates p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001. c Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all four groups (Sham, N = 3; GFP, N = 1; PBS, N = 4; cBIN1, N = 4). Significance was calculated using a Log-rank test.

At each terminal study, myocardium was sampled at five sites across left ventricles (anterior free wall, posterior free wall, apex, base, septum) for mRNA extraction and confirmation of successful exogenous gene expression introduced by AAV9. Specifically, transcription of AAV9-cBIN1/GFP-V5 genes was detected by a custom-made Taqman probe detecting the V5 tag sequence and normalized to a minipig housekeeping gene HPRT1 using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis. For all AAV9-treated animals, the inclusion criteria are a confirmed transcription of the exogenous gene in the LV myocardium. As indicated in Fig. 2b, transcription of GFP-V5 is confirmed in LV myocardium from the AAV9-GFP injected minipig (∆∆Cq of 4.1 ± 1.8 vs. 1.0 ± 0.1 in PBS controls, p < 0.05). Transcription of cBIN1-V5 is also confirmed in 4 out of 5 AAV9-cBIN1 injected minipigs (∆∆Cq between 2.6 ± 0.7 and 9.2 ± 3.4 in each of the four animals with an overall average at 4.5 ± 1.1, p < 0.05-0.001 when compared to PBS controls) (Fig. 2b). The fifth AAV9-cBIN1 treated animal (cBIN1-5, Fig. 2b) failed to express exogenous cBIN1-V5 gene (∆∆Cq of 1.1 ± 0.3), and thus failed to meet inclusion criteria. As indicated in Fig. 2c (purple survival curve), all four minipigs with a successful AAV9-cBIN1 transduction survived to the preset 6-month treatment endpoint without signs of HF. In contrast, all four minipigs in the PBS treatment group developed severe HF symptoms resulting in premature non-survival at 6, 49, 69, and 135 days post-injection, respectively (Fig. 2c, red survival curve). Similar to PBS treatment, the minipig treated with AAV9-GFP with a confirmed GFP-V5 expression (Fig. 2b) also died of severe HF at 52 days post injection (Fig. 2c, green survival curve). Comparison of the survival curves identified a significant difference across four groups, with the 6-month survival rate improved to 4/4 (100%) in the cBIN1-treatment group from the PBS group of 0/4 (0%) and the GFP group of 0/1 (0%). Given the similar survival and HF development between PBS and GFP treatment, all animals in these two groups are combined as a control treatment group for further analysis.

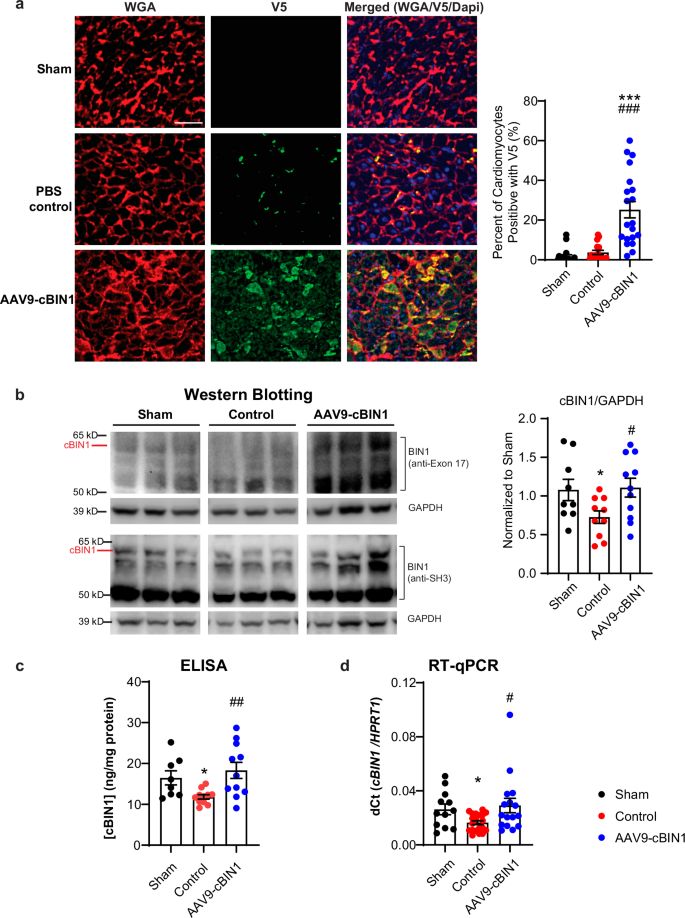

We then explored the cardiomyocyte transduction efficiency of AAV9-cBIN1, as well as the overall cBIN1 gene and protein expression (exogenous and endogenous included) in the minipig hearts across the three groups. Using immunofluorescent labeling with an antibody against the V5 tag, we quantified the spatial expression of AAV9-transduced exogenous cBIN1-V5 protein in LV myocardial cryosections from each group. In AAV9-cBIN1 treated animals, 25.2 ± 4.1% of cardiomyocytes are positive in V5 signal, whereas background in animals without AAV9 treatment is minimal (Fig. 3a). These data indicate that in minipigs receiving a single low systemic dose of AAV9-cBIN1 (6 × 1011 vg/kg, IV), there are over 20% of cardiomyocytes still expressing exogenous protein 6 months post-injection. Western blotting analysis further identified that protein expression of cBIN1 (the protein band marked in Fig. 3b which can be detected by both antibodies against BIN1 exon 17 and SH3 domain) in LV of HFrEF minipigs is reduced 33% from healthy sham hearts and can be normalized by AAV9-cBIN1 treatment (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 3). ELISA quantification of [cBIN1] (ng/mg protein) in LV free wall samples identified a similar reduction in HFrEF minipigs with a rescue from AAV9-cBIN1 treatment (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, using RT-qPCR with a probe detecting a species-conserved sequence at the exonal junction between exons 13 and 17, we were able to quantify the overall cBIN1 gene expression in LV from these animals. Similar to changes of cBIN1 protein analyzed by Western blotting and ELISA, cBIN1 gene expression in LV is reduced in HFrEF minipigs when compared to healthy sham minipigs and rescued by AAV9-cBIN1 treatment (Fig. 3d). Taken together, these data indicate that in the LV from minipigs with RVP-induced non-ischemic DCM and HFrEF, cBIN1 gene and protein expression in failing cardiomyocytes is significantly reduced and can be restored.

a Representative images of left ventricular myocardial cryosections labeled with WGA (red), V5 (green), and Dapi (blue) from each group (Scale bar: 50 μm) with quantification to the right for the percent of cardiomyocytes positive with V5 signal (images/hearts: n/N = 19/2; 16/2, 20/3 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups). b Representative Western blots of cBIN1 detected by antibody against BIN1 exon 17 or SH3, as well as loading control GAPDH in LV samples from each group. Quantification of cBIN1 protein band (cBIN1/GAPDH and normalized to Sham group) is included in the bar graph to the right (LV samples/hearts: n/N = 9/3; 10/5, 11/4 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups). c ELISA quantification of [cBIN1] (ng/mg protein) in LV (LV samples/hearts: n/N = 8/3; 11/5, 11/4 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups). d RT-qPCR quantification of cBIN1 gene expression in LV (LV samples/hearts: n/N = 12/3; 20/5, 16/4 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD test or non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test is used for comparison among three groups. *, *** indicates p < 0.05, 0.001 for comparison vs. Sham. #, ##, ### indicates p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 for comparison vs. Control.

Next, in these AAV9-cBIN1 treated HFrEF minipigs with confirmed exogenous cBIN1-V5 transduction in the heart, we explored potential transgene transcription and toxicity in other organ tissues. Using the same RT-qPCR analysis for the V5 tag (V5/HPRT1), we identified that at 6 months post-injection, there is no cBIN1-V5 transgene transcription detected in spleen, skeletal muscle, kidney, and lung (∆∆Cq ≤ 1 of the PBS background, Supplementary Fig. 1). One of the four animals (cBIN1-2) had a detectable gene transcription in the liver at a level lower than the maximal expression detected in the heart samples from the same animal (Supplementary Fig. 1). These data indicate that 6 months after administration, a low dose systemic injection of AAV9-cBIN1-V5 (6 × 1011 vg/kg, IV) induces a relative cardiac selective transduction of exogenous cBIN1-V5 gene with minor transduction in the liver. Blood tests every 1–2 weeks (comprehensive complete blood count as well as hepatic and renal blood chemistry panels) (Table 1) also identified no post-treatment abnormalities, indicating no liver toxicities due to transgene expression. Furthermore, terminal histopathology analysis by independent specialized veterinary pathologists identified no abnormality, indicated as “unremarkable” findings, in main organ systems including brain, spinal cord, kidney, adrenal gland, spleen, lymph node, thymus, pancreas, gallbladder, ovary, and adipose tissue (Supplementary Fig. 2). The findings in lung and liver range from “unremarkable” to “mild inflammation or mild congestion”, indicating a result of HFrEF development in these animals with improvement from cBIN1 therapy. The representative images with independent histopathology diagnosis are included in the Supplementary Fig. 2.

AAV9-cBIN1 rescues hemodynamics in HFrEF minipigs

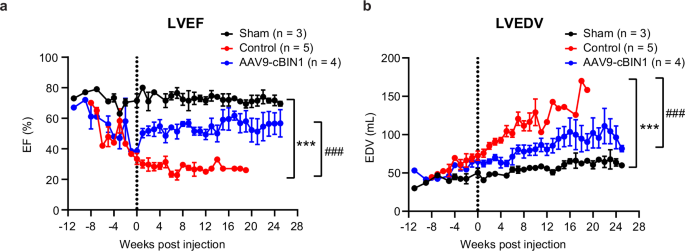

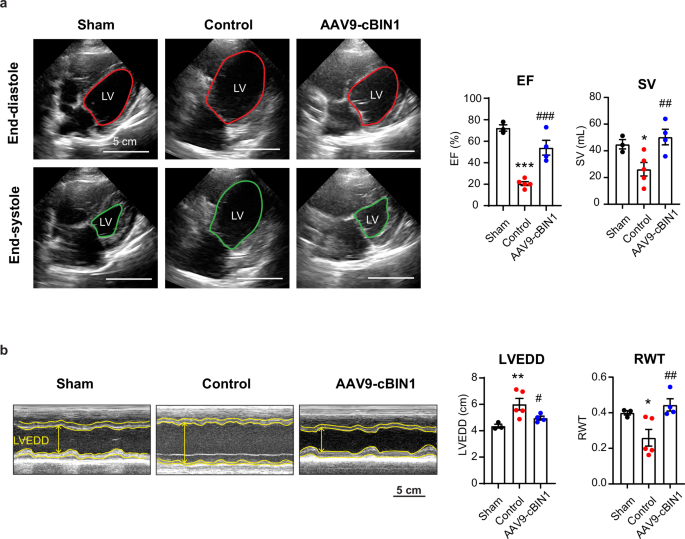

Next, we analyzed the longitudinal changes of echocardiogram-measured cardiac function and geometry parameters in all groups. As demonstrated in Fig. 4 and Table 1, when compared to the healthy sham group (black curve), the two RVP-HF groups (red and blue curves) developed tachypacing-induced DCM and HFrEF at a similar pace prior to treatment intervention as evidenced by increased LVEDV (Fig. 4a) and reduced LVEF (Fig. 4b). Following control treatment (week 0), the RVP-HF minipigs continued disease progression with LVEF further decreasing to 20.6 ± 1.8% and LVEDV dilated to 125.4 ± 17.7 mL at termination. On the other hand, AAV9-cBIN1 treated minipigs exhibited LVEF recovery with limited further LV dilation (Fig. 4a, b). The therapeutic efficacy of AAV9-cBIN1 lasted for at least 6 months post-injection with the terminal LVEF maintained at 54.0 ± 6.9% and LVEDV at 96.2 ± 14.8 mL. Compared to control treatment, AAV9-cBIN1 significantly improved LV systolic function with a significantly improved LVEF and a completely restored stroke volume (SV) (Fig. 5a). The DCM phenotype with an eccentric hypertrophic remodeling of LV (RWT↓ and LVEDD↑) in control minipigs is also improved by AAV9-cBIN1 treatment (Fig. 5b). The rescued E/e’ found in AAV9-cBIN1 treated minipigs (Table 1) further indicates a beneficial effect of cBIN1 therapy on diastolic function. These results indicate that an unprecedented recovery of cardiac function can be induced by a single intravenous dose of AAV9-cBIN1 which also lasts for at least 6 months post-treatment. Furthermore, weekly electrocardiography interrogation confirmed pacing-induced continuous RVP and normal intrinsic sinus rhythms when RVP was turned off during interrogation. No premature ventricular contractions or ventricular arrhythmias were detected in animals from all three groups. Sporadic incidences of blocked premature atrial contraction occur in half of the animals similarly at baseline and after treatment across all three groups. These data indicate that the therapeutic benefit of AAV9-cBIN1 in improving cardiac performance does not come at the cost of increased arrhythmia burden.

Echocardiography monitoring of LVEF (a) and LVEDV (b) in minipigs from baseline (RVP initiation timepoint) to terminal endpoint for each group (N = 3, 5, 4 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD test for comparison among three groups was performed. *** indicates p < 0.001 for comparison vs. Sham. ### indicates p < 0.001 for comparison vs. Control.

a Representative four-chamber view images of the minipig heart at end diastolic (top) and systolic (bottom) phases on termination day (left). Quantification of ejection fraction (EF) and stroke volume (SV) from each group (N = 3, 5, 4 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups), (right). b Representative images of M-mode short axis view of the heart at termination (left). Quantification of left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) and relative wall thickness (RWT) (N = 3, 5, 4 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups) (right). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test is used for comparison among three groups. *, **, *** indicates p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 for comparison vs. Sham. #, ##, ### indicates p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 for comparison vs. Control.

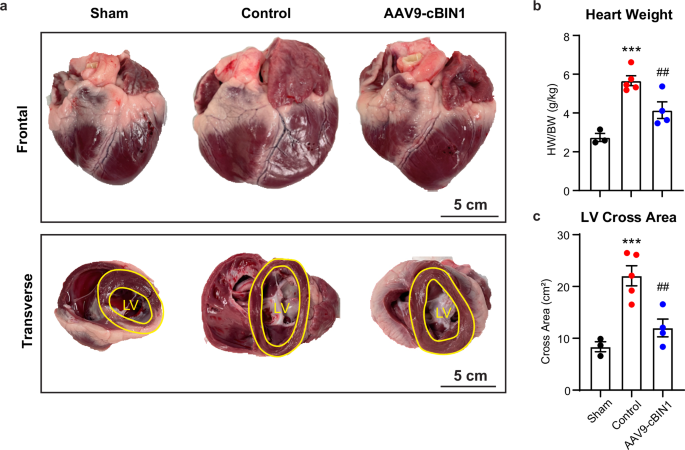

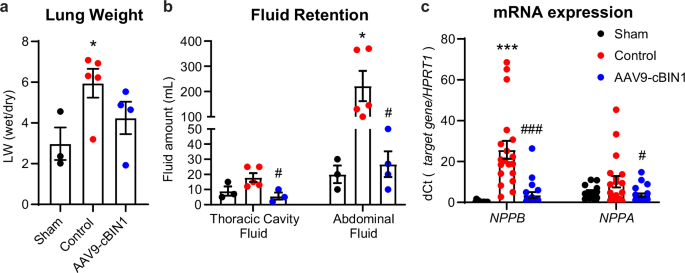

AAV9-cBIN1 rescues heart anatomy and fluid retention in HFrEF minipigs

Gross heart morphology and LV chamber sizes were also analyzed at the time of animal termination. The control minipigs progressed to severe DCM with increased heart weight and enlarged LV cross area when compared to the sham group. In contrast, these parameters were significantly improved by AAV9-cBIN1 treatment (Fig. 6a–c). When compared to control-treated RVP-HF animals, AAV9-cBIN1 treated minipigs had less lung edema as measured by ratio of wet/dry lung weight (Fig. 7a), as well as less thoracic cavity and abdominal fluid retention (Fig. 7b). The mRNA expression levels of Natriuretic Peptide B (NPPB) and Natriuretic Peptide A (NPPA), two commonly used cardiac biomarkers for myocardial stretch induced by excessive fluid overload, were also significantly reduced in the left ventricles from the AAV9-cBIN1 treated minipigs compared to the controls (Fig. 7c), further indicating rescue of cardiac performance and fluid retention by cBIN1 therapy.

a Frontal and transverse view of gross morphology of the minipig heart at termination. Scale bar, 5 cm. b Quantification of heart weight normalized to body weight. c Quantification of left ventricular (LV) cross area from transverse view (N = 3, 5, 4 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test is used for comparison among three groups. *** indicates p < 0.001 for comparison vs. Sham. ## indicates p < 0.01 for comparison vs. Control.

a Lung weight (LW) measured as the ratio of wet over dry lung weight of the minipigs at termination. b Thoracic cavity and abdominal fluid volume measured during termination procedure. c The mRNA level of Natriuretic Peptide B (NPPB) and Natriuretic Peptide A (NPPA) normalized to the housekeeping gene HPRT1 (quantified by ΔCt of NPPB/HPRT1 or NPPA/HPRT1) (LV samples/hearts: n/N = 15/3; 19/5, 20/4 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test or non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by uncorrected Dunn’s test is used for comparison among three groups. *, *** indicates p < 0.05, 0.001 for comparison vs. Sham. #, ### indicates p < 0.05, 0.001 for comparison vs. Control.

Note all the terminal analyses were performed at 6 months post-treatment with continuous RVP in the AAV9-cBIN1 group. In contrast, control RVP-HF animals had to be terminated much earlier at 8.9 ± 3.0 weeks post-treatment. Yet, despite a much shorter RVP duration, a more severe DCM and HFrEF phenotype is seen in control animals (Figs. 5–7), further highlighting the potency and duration of the therapeutic efficacy provided by cBIN1 gene therapy.

AAV9-cBIN1 normalizes t-tubule ultrastructure in HFrEF minipig cardiomyocytes

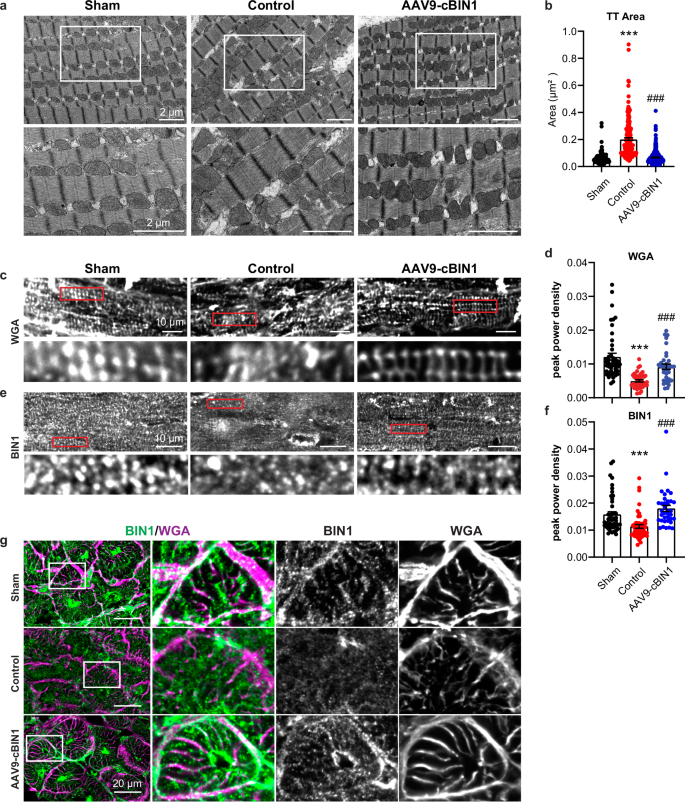

Because cBIN1 exerts its biological function by creating membrane microfolds at cardiac t-tubules for microdomain formation, housing the calcium handling machinery7, we explored the ultrastructure of t-tubule membrane in cardiomyocytes using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging. In RVP-HF control minipig myocardium, the t-tubule lumen is significantly dilated from that seen in healthy sham hearts, which is normalized (reversed) by AAV9-cBIN1 therapy (Fig. 8a, b). Next, we explored t-tubule organization via fluorescent imaging of LV myocardial cryosections with t-tubule labeling either by wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) or antibody against BIN1 (clone 99D, anti-BIN1 exon 17). Power spectrum analysis of the peak power density of either WGA (Fig. 8c, d) or BIN1 (Fig. 8e, f) signal in cardiomyocyte longitudinal sections identified a significant reduction of t-tubule periodicity in HFrEF cardiomyocytes, a phenotype consistent with literature reported t-tubule remodeling in HFrEF hearts14,21. AAV9-cBIN1 treatment was able to normalize t-tubule organization in failing cardiomyocytes. Imaging of cardiomyocyte cross sections with co-labeling of WGA and BIN1 further revealed that BIN1 (green) localizes to WGA (magenta) labeled t-tubules (Fig. 8g).

a Representative transmission electron microscopy images of left ventricular free wall of minipig hearts with zoomed-in images of the boxed area (left). Scale bar, 2 µm. b Quantification of transverse-tubule (TT) cross-sectional area in each group (TT/hearts: n/N = 221/2; 203/3, 306/3 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups) (right). c–f Representative images with power spectrum analysis for BIN1 (c, d) and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) (e, f) in myocardial sections from each group. (cells/hearts: n/N = 47/2; 51/3, 36/3 for BIN1; 46/2; 45/3, 34/3 for WGA from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups). Scale bar, 10 µm. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by uncorrected Dunn’s test is used for comparison among groups. *** indicates p < 0.001 for comparison vs. Sham. ### indicates p < 0.001 for comparison vs. Control. g Cross-sectional views of cardiomyocyte images indicate colocalization between BIN1 (green) and WGA (magenta). Group labels are included to the left of the images. Scale bar, 20 µm.

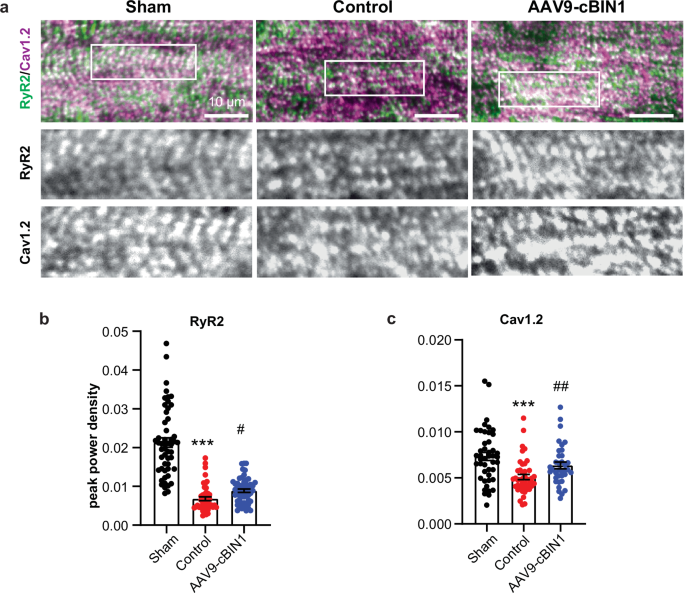

Next, spinning-disc confocal imaging of the dyad proteins RyR2 and the pore-forming subunit Cav1.2 of the LTCC were obtained from immunofluorescence labeled cryosections of the LV myocardial free wall. As indicated in the representative images in Fig. 9a, due to localization to the t-tubule and jSR areas, the dyad proteins (green, RyR2; magenta, Cav1.2) are well organized in healthy cardiomyocytes from sham animals, which become disorganized in control-treated HFrEF cardiomyocytes and can be improved by AAV9-cBIN1 treatment. Power spectrum analysis further identified that the peak power densities of RyR2 and Cav1.2 distribution in control-treated HFrEF cardiomyocytes are significantly lower than those of healthy cardiomyocytes from sham animals, with a partial rescue from AAV9-cBIN1 treatment (Fig. 9b, c). These data indicate that cBIN1-restored t-tubule ultrastructural membrane curvature and organization underline the observed phenotypic rescue of HFrEF, achieving rescue of heart function by reorganizing t-tubule microdomains which house calcium handling proteins to facilitate EC coupling.

a Representative confocal images of ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2, green) and L-type calcium channels (Cav1.2, magenta) labeled myocardial sections from each group. Scale bar, 10 µm. b–c Quantification of RyR2 (b) (cells/hearts: n/N = 52/2; 47/3, 55/3 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups) and Cav1.2 (c) (cells/hearts: n/N = 45/2; 45/3, 36/3 from sham, control, and cBIN1 groups) peak power density in cardiomyocytes from each group. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test is used for comparison among three groups. *** indicates p < 0.001 for comparison vs. Sham. ### indicates p < 0.001 for comparison vs. Control.

Discussion

In this study, we report in swine the efficacy of an AAV9-based gene therapy replenishing cBIN1 to recover the subcellular architecture of failing cardiomyocytes for functional rescue of non-ischemic DCM and HFrEF. Transduction of exogenous cBIN1 across the left ventricles of failing hearts can be successfully induced by a single intravenous low dose of AAV9-cBIN1 to produce a robust and lasting rescue of LV contractile dysfunction with limited LV chamber dilation. These data provide strong evidence in support of the therapeutic efficacy of AAV9-cBIN1 in large mammals with HFrEF. Moreover, the strength of LV free wall myocardial cBIN1 in correlating with LV remodeling and dysfunction in human patients with HFrEF (Fig. 1) further supports the promising potential to translate cBIN1 gene therapy to humans.

Over the past decade, the concept of inducing specific beneficial cardiac proteins by gene therapy to mitigate and even cure HF has been appealing3,5,6. Some therapeutic targets that have been tested in preclinical or clinical trials include adenylyl cyclase 6, S100A1, β-adrenergic kinase-ct (βARKct), SERCA2a, urocortins, and B-cell lymphoma 2-associated anthanogene-33. However, the clinical outcomes of the current trials, though informative, are not satisfactory regarding the efficacy in HF patients. Challenges of the translational feasibility of gene therapy include a lack of effective target genes, applicable dosage, and proper delivery methods5,6. Fortunately, the AAV9-cBIN1 approach described here addresses many concerns based on strong preclinical data in mice10,13,14 and swine10.

As an upstream master regulator organizing t-tubule microdomains crucial to the dynamic beat-to-beat intracellular calcium transients, cBIN1 not only promotes the LTCC-RyR dyad formation for efficient EC coupling, but also recruits SERCA2a for effective diastolic calcium removal7,8,9,10. The multifaceted functional components regulated by cBIN1 support its potential therapeutic efficacy. We emphasize that introducing an upstream regulation such as cBIN1 is more potent than introducing a downstream regulation such as SERCA2a. The therapeutic inability of exogenous SERCA2a to improve failing hearts3,22,23 gives additional impetus to working with an upstream regulator. The potency of AAV9-cBIN1 can be seen in its therapeutic effectiveness at a low dose of 6 × 1011 vg/kg, IV, which effectively transduces near a quarter of cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3a) maintained at least for 6 months with limited transduction in other organs (Supplementary Fig. 1). This dose is close to the lowest tested therapeutic dosage reported in phase I/II clinical trials24,25 and 1–3% of the dosage in phase III trials26,27 for other AAV9-based gene therapies. As a result, we can use a low dose of CMV-promoted AAV9 vector with high and selective cardiac transduction efficiency28,29, avoiding the unwanted off-target toxicities in other organs (Supplementary Fig. 2) normally associated with higher viral doses. The low dose strategy is also amenable to a simpler but less efficient systemic intravenous delivery route, thus avoiding complications associated with more invasive viral delivery methods such as catheter-based intra-endocardial injections.

Nonetheless, AAV9-induced immunogenicity that can lead to low transduction efficiency of cBIN1 remains challenging, even though AAV9 was reported to be less immunogenic than other serotypes given its unique less “pointed” capsid surface compared to other serotypes30. In the current study, one out of five minipigs (cBIN1-5, Fig. 2b) injected with AAV9-cBIN1 failed to express cBIN1 transgene, possibily due to a high level of neutralizing antibodies (NAb) to AAV9 in this animal. The pre-existing NAb to AAV9, found to range from 15 to 30% in humans31, can blunt the viral transduction efficiency and limit the target population and dosing frequency in clinical trials. Hence, animal and human subjects may need prescreen for the AAV9-NAb level. On the other hand, the potency of cBIN1 therapy may provide additional benefits with more room for dose escalation to overcome issues related to pre-existing NAb.

In conclusion, our study provides strong evidence in a large mammal translational model that a systemic low dose of AAV9-cBIN1 can rescue cardiac performance and improve mortality via normalizing cardiomyocyte membrane architecture. The success of cBIN1 gene therapy in swine with non-ischemic HFrEF can be a gateway to future clinical trials testing its efficacy in patients with HFrEF. The limitations of our current study include relatively small sample size (3-5 large animals per group), the potential need to validate our findings in a non-RVP model, and the use of the V5-tagged mouse cBIN1 gene. However, cBIN1 has over 95% sequence homology among species between mouse, swine, and human. The same AAV9 vector carrying the human cBIN1 gene without the V5 tag is currently being generated for human clinical trials. We also expect similar positive results from other large animal HF models, and look forward to such follow-up studies.

Methods

Ethics statement for human samples and animal models

Human myocardial tissues and echocardiography measurements were acquired from patients with DCM and chronic advanced HF with reduced ejection fraction at the time of heart transplant surgery and non-HF donors (not accepted for human transplant due to non-cardiac reasons) according to the approved protocol IRB-00030622. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All human samples and clinical data-related studies were in accordance with the ethical principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All human tissues were procured from the University of Utah Hospital and not from prisoners. For animal studies, the experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Utah under Protocol #00001636 and was performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Generation of adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9) vector

cBIN1 (the mouse gene of cardiac spliced BIN1 isoform containing exons 13 and 17) or GFP (a negative control) sequence with a V5 tag at the C terminus was constructed on cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoted AAV9 vector backbone for cardiotropic expression13. Plasmid construction and AAV9 virus generation were custom-produced at Welgen Inc. using a detailed method described in our previous study13.

Animals and experimental protocol

5–7 months old male and female Yucatan minipigs were purchased from S&S Farms DBA Premier BioSource and housed in the comparative medicine center of the University of Utah. Animals were housed in temperature-controlled room with a 12:12 light-dark cycle and access to water and food. After acclimation and training period, all minipigs (n = 13, 7 females and 6 males) received pacemaker (donated from Medtronic) implantation with a right ventricular apical pacing lead under general anesthesia. All 13 minipigs survived the pacemaker implantation procedure without complications. Right ventricular rapid pacing (RVP) was initiated at 170 beats per minute (bpm) in 10 minipigs after recovery from implantation surgery, and 3 randomly selected minipigs (1 female and 2 males) that underwent pacemaker implantation but without RVP initiation served as the healthy sham group. All minipigs underwent sedation induction and were monitored by echocardiogram, electrocardiogram, and bloodwork analysis from pacemaker implantation to the end of the study every 1–2 weeks. The 10 minipigs receiving RVP induction were randomized into the control group (n = 5 treated with PBS, 2 females and 2 males, or AAV9-GFP, 1 male) and AAV9-cBIN1 group (treated with AAV9-cBIN1-V5, n = 5, 4 females and 1 male) after echocardiogram confirmed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) lower than or equal to 40% for 2 weeks and then were intravenously injected with AAV9 vectors (6 × 1011 vg/kg, IV.) or equal volume of vehicle solution PBS through the ear vein under sedation. Continuous RVP and monitoring were maintained throughout the study. Minipigs were terminated when severe HF was developed and required ethics committee-mandated euthanasia or at the 6-month post-treatment endpoint. In summary, the preset ethics committee-mandated euthanasia criteria include dyspnea, edema, anorexia, loss of appetite, physical inactivity, severe weight loss or increase (change of 10% of body weight within a week), and/or clinical lethargy. Euthanasia was performed in accordance with the current AVMA guidelines. Prior to general anesthesia, the minipig was sedated with midazolam 0.5 mg/kg IM, hydromorphone 0.1 mg/kg and alfaxalone 1–5 mg/kg as needed, IV/IM, intubated and maintained with Isoflurane 0–5% INH, Propofol 3-10 mg/kg IV or alfaxalone 1–5 mg/kg. The thorax was opened via sternotomy or lateral thoracotomy. A pre-mortem cardiac free wall punch biopsy was collected and then the heart was removed. Postmortem examination was performed at the termination endpoint. Physiological parameters including body weight, pericardial/abdominal fluid volume, heart and lung weight were obtained. Biopsy samples were collected from left ventricular free wall for TEM. Gross morphological pictures of the heart were obtained, and the left ventricular cross area was measured using Fiji ImageJ. Heart tissues were collected from 5 sites of the left ventricle (anterior and posterior free wall, septum, base, apex) for mRNA extraction. Other organ samples were fixed in formalin and sent to Zoetis Reference Laboratories for H&E staining and histopathology diagnosis by specialized veterinary pathologists. A complete checklist of the ARRIVE Essential 10 is included in Supplementary Table 1. The experimental protocol was summarized in Fig. 2a (Created with BioRender.com).

Myocardial tissue cBIN1 quantification

Myocardial tissues were homogenized in 1% Triton lysate buffer (1% Triton, 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM Sodium orthovanadate, Halt™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail). Protein lysates were tested for cBIN1 concentration using a commercially available ELISA kit (Sarcotein Diagnostics, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Myocardial cBIN1 concentration was then normalized to the total protein level quantified by the BCA protein assay (Bio-Rad, USA). Protein lysates from the LV free wall samples from each group were also used for Western blotting analysis using previously established protocol13. Detection of cBIN1 was achieved by primary antibody against BIN1 exon 17 (ms anti-BIN1, Clone 99D, Sigma) or SH3 domain (rb anti-BIN1, Abcam). GAPDH (Rb anti-GAPDH, Abcam) was blotted as the loading control. cBIN1 band was quantified and normalized to GAPDH and expressed as the ratio to the average levels of the sham group.

Echocardiography

Weekly or biweekly echocardiography for minipigs was performed after the RVP was temporarily stopped for 20 min to obtain an equilibrated cardiac function evaluation using Lumify handheld ultrasound system (Philips, USA) and Acuson ultrasound system (Simens Medical Solutions Inc, USA). After the acquisition of echocardiography recording, minipigs were immediately paced back to 170 bpm to ensure continuous tachypacing throughout the study. The total non-pacing period for each recording session was limited to 30 min. Lumify recorded B-mode videos for two-dimensional four-chamber view were used to measure the left ventricular area and longitudinal axis length at end-diastole and end-systole phases using Fiji ImageJ. LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) and end-systolic volume (LVESV) were calculated based on Biplane Simpson’s volume formulation32:

-

(1)

(LV Volume = 0.85 × (LV Area)2/longitudinal length)

as recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography. Other systolic parameters were calculated as below:

-

(2)

LV stroke volume (SV) = LVEDV–LVESV

-

(3)

LVEF = (LVEDV-LVESV)/LVEDV

-

(4)

LV cardiac output (CO) = SV × heart rate (HR)

M-mode images of LV short axis view were obtained using Lumify with the measurement of LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), end-diastolic septum wall thickness (SWTd), and end-diastolic posterior wall thickness (PWTd) using Fiji ImageJ. Relative wall thickness (RWT) and LV mass (LVM) were calculated using the equation below:

-

(5)

RWT = (SWTd + PWTd)/LVEDD

-

(6)

LVM = 0.8 × (1.04 × (LVEDD + SWTd + PWTd)3 – LVEDD3) + 0.6

Diastolic echocardiography was obtained and measured using Acuson pulse-wave Doppler and tissue Doppler mode in a four-chamber view for mitral blood inflow velocity (E, A wave) and mitral annular velocity (e’ wave). All echo parameter final results were generated using an average of 3–4 cardiac cycle measurements.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

At termination, a punch biopsy was performed on the LV free wall for TEM sample collection. The detailed method of TEM sample preparation was described in a previous study13. In brief, punched myocardial tissue was sliced and stored in 10 mL of ice-cold fixative (2% PFA and 2% Glutaraldehyde in PBS buffer) and sent to the Electron Microscopy Laboratory at the University of Utah at 4 °C in fixative. Sliced tissue was then fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide and pre-stained with uranyl acetate following dehydration of tissue slices in ethanol and 100% acetone. The tissue was then embedded with epoxy resin, sectioned at 70 nm, and post-stained with acetate and lead citrate. Stained sections were imaged using JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope (Gatan Inc, USA). T-tubule transverse area was measured using Fiji ImageJ.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from 5 sites of left ventricular myocardial tissue (anterior and posterior free wall, septum, base, apex) and other organs (liver, spleen, skeletal muscle, kidney, and lung) in each pig using TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA) and PureLink RNA extraction kit (Invitrogen, USA). Genome DNA contamination in extracted RNA samples was digested using a TURBO DNA-free kit (Invitrogen, USA). cDNA was then synthesized using a SuperSript IV VILO Master Mix kit (Invitrogen, USA). A customized V5 probe (Thermofisher, USA) was used to detect exogenous transgene mRNA expression in myocardial and other organ tissues normalized to the housekeeping gene HPRT1 (Thermofisher, USA). NPPB and NPPA (Thermofisher, USA) mRNA expression were detected in LV myocardial tissues normalized to HPRT1. TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermofisher, USA) was used for RT-PCR examination.

Myocardial cryosection labeling, spinning disc confocal microscopy, and imaging analysis

Myocardial tissue was collected from the LV free wall for IF staining. A detailed method was described previously10. In brief, Tissue slices were embedded and flash frozen in OCT compound and stored at −80 °C before sectioning at 10 μm. Frozen tissue cryosections were fixed in acetone and permeabilized in a buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 5% normal goat serum, and 1 × PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Tissue sections were then labeled with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated WGA (Invitrogen, USA) for 1 h at room temperature and mounted with DAPI containing Prolong® Gold media (Invitrogen, USA). For immunofluorescent labeling, fixed and permeabilized tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies (rb anti-V5, Sigma; ms anti-BIN1, clone 99D, Sigma; ms anti-RyR2, Abcam; or rb anti-Cav1.2, Alomone Lab) overnight at 4 °C followed by washes and incubation with Alexa fluor-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Imaging of cardiac tissue sections was obtained using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope with a SoRa spinning-disk confocal unit (Yokogawa, Japan) and NIS Elements software (Nikon, Japan). The WGA and BIN1 labeled membrane structure and calcium handling proteins RyR2 and Cav1.2 in confocal images were analyzed for frequency domain power spectrum by Matlab using FFT conversion with peak power density quantification as previously described8,33,34.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Prism 10 software (GraphPad, USA). All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Normality was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test or nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was performed to compare the two groups. Correlation between variables was analyzed using the Pearson correlation test followed by linear regression analysis. One-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD test or non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by uncorrected Dunn’s test was performed to compare three groups. Two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD test for multiple comparisons was used to determine differences among treatment groups in time course. A log-rank test was performed to compare Kaplan-Meier survival curves among groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Responses