Catalyzing changes on the ground and up: evidence from 106 ENGOs in community waste management in China

Introduction

The issue of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) has grown increasingly severe, exacerbating resource depletion and environmental pollution1,2,3,4. China, being the world’s largest waste producer, faces enormous challenges5. To address these challenges, the Chinese government has implemented various waste separation and recycling policies (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Urban communities play a vital role in these solutions, particularly in fostering public compliance with waste sorting6,7,8.

Despite two decades of government interventions, China has seen limited achievements in waste sorting. To date, the focus has mainly been on hardware investment and public participation has been largely overlooked9,10. Consequently, research indicates that waste management must be addressed not only as a technical challenge, but also as a social problem, involving individual behavioral change9,11,12.

Evidence shows that environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) play a crucial role in this effort due to their special capabilities, resources, and strategies13,14. They can educate and engage the public in community-based waste sorting, and some Chinese governments are beginning to recognize their value in addressing the issue of MSW10,15. From 2012 to 2021, national political authorities issued several policy documents to foster ENGOs’ involvement in community waste management (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

Empirical cases from various countries, including Romania16, Spain17, Singapore18, Malaysia19, Iran20, India21, and Bangladesh22 show that ENGOs significantly influence public opinion and promote recycling behavior16,23,24,25. While there are high expectations for ENGOs to engage diverse stakeholders in waste management in China26, their specific roles and contributions remain unclear due to limited visibility and accessibility26. This research examines the efforts and contributions of ENGOs involved in urban community waste management within the unique authoritarian institutional context of China. It aims to highlight their positive roles in bridging stakeholders at various levels and fostering innovations in sustainable waste management and social practices.

This research draws on the concepts of actors’ roles in sustainability experiments. Their actions, resources, expectations, strategies, and interventions influence the success of these experiments13,14,27, which are key tools for finding alternative solutions to promote sustainability transitions28,29,30. Literature shows that ENGOs fulfill a more quintessential role as transition intermediaries31,32, facilitating changes in sectors like mobility33, energy34,35, plastic repurposing36, and agro-food37. Their documented roles include articulating needs34,38,39,40, building networks38,41,42, developing and diffusing knowledge34,42,43,44, and connecting niche-level45 (spaces in which radical innovations and experimentation are taking place) experiments with regime level45 (relatively stable and shared configurations of technologies, practices and institutions) actors to support sustainable institutional infrastructure dvelelopment35,36(see Supplementary Table 1 for more detailed roles). The literature also emphasizes the importance of examining ENGOs’ predominance, interactions, collaborations, and coordination in sustainability experiments within the waste management sector27.

Here we present the first nationwide examination of ENGOs’ roles in Chinese community waste management. We explore the following key questions: What roles do ENGOs assume in the transition to sustainable waste management in China? How do ENGOs operate and collaborate effectively? What challenges do they encounter, and how do they address these obstacles? We surveyed 106 ENGOs and conducted an in-depth analysis of 26, identifying their specific roles and challenges. By analyzing these roles and challenges, our research highlights the importance of ENGOs in accelerating the transition toward sustainable community waste management in China.

Results

Overview of the roles and challenges of 106 ENGOs

The survey encompassed 106 ENGOs across 21 municipalities in China (see supplementary Fig. 3). These ENGOs, representing some of the most active participants in this sector (see Supplementary Notes 1 and 2 for details), provide a valid reflection of ENGOs’ practices and roles working in community waste management in China. They focus on various areas, including waste prevention, reduction at the source, reuse, recycling, and repurposing (see Supplementary Fig. 4).

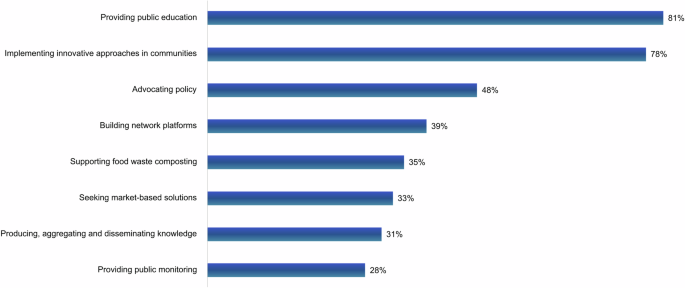

Figure 1 offers an overview of studied ENGO roles in Chinese community waste management. Public education and advocacy (81%) and front-line practitioners (78%) are the predominant roles. Additionally, there are 48% of ENGOs engaging in policy advocacy. About 30–40% of ENGOs focus on platform and network support, technical support, industry talent training, and knowledge production, indicating a growing supportive industry ecosystem. ENGOs involved in public monitoring are rare (28%), and those providing financial support are the scarcest (7%).

The bar length represents the percentage of the 106 ENGOs surveyed that adopt the particular role.

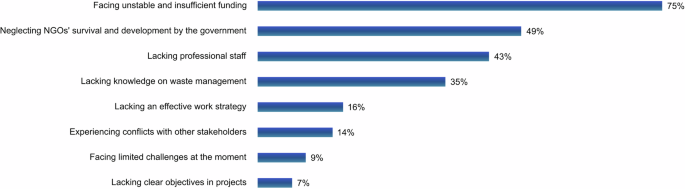

Approximately 75% (n = 79) of respondents face challenges of insufficient funding and resources (see Fig. 2). Other struggles include unstable human resources (n = 46), limited vision (n = 43), lack of effective work strategies (n = 39), and lack of professional knowledge (n = 37). In response to open-ended questions, participants reported challenges encompassing government neglect of ENGO growth and survival, conflicts with other stakeholders, and difficulties in raising awareness and changing public behaviors.

The bar length represents the percentage of the 106 ENGOs surveyed that face the particular challenge.

In-depth exploration of 26 ENGOs’ roles

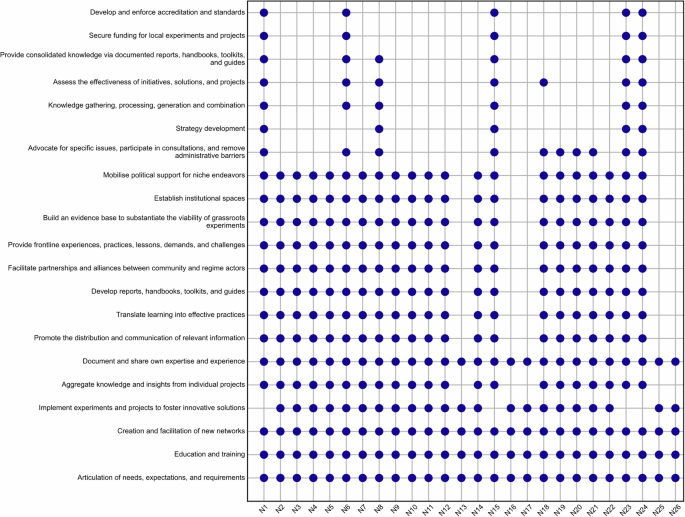

We conducted interviews with representatives from a subset of 26 ENGOs (see Methodology for detailed rationale). Information on these 26 ENGOs, along with identifiers (N1, N2…, and N26) is presented in Table 1. A summary of activities conducted by these ENGOs is provided in Supplementary Note 3. Drawing on the roles of ENGOs in sustainability experiments literature (Supplementary Table 1), Fig. 3 provides a detailed classification of these 26 ENGOs’ roles.

The horizontal labels N1–N26 represent the 26 ENGOs. Vertical labels show 21 roles identified from sustainability experiment literature. The dot is positioned to show which roles each ENGO fulfills.

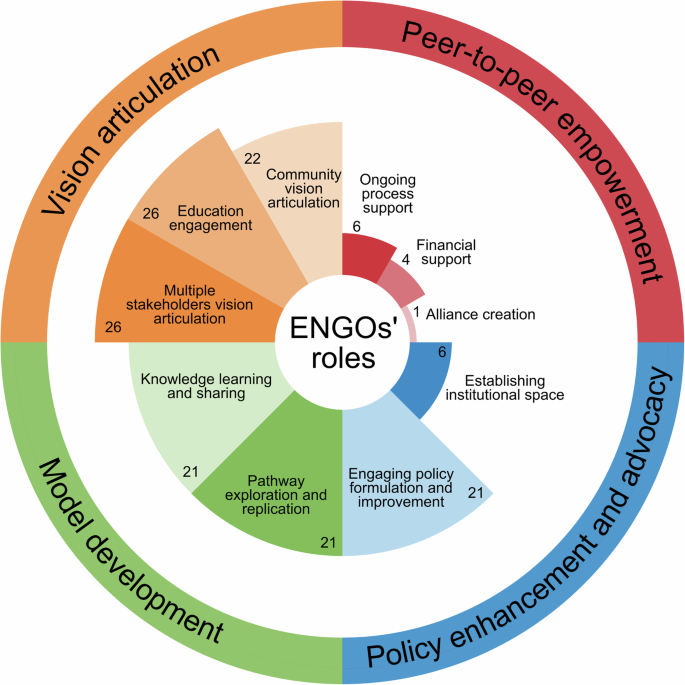

Upon closer scrutiny of our data, we identified four role categories of ENGOs: vision articulation, model development, policy enhancement and policy advocacy, and peer-to-peer empowerment. Due to limited space, we elaborate on these four main roles of 26 ENGOs according to Fig. 4.

The numbers indicate how many of the 26 ENGOs fulfill each particular role.

The first primary role of 22 of the 26 ENGOs (all except N1, N15, N23, and N24) is to create inclusive initiatives that engage the community, mobilize more residents, and involve them in sustainable actions. Their goal is to raise residents’ environmental awareness and articulate expectations toward a better living environment.

The ENGOs studied use two approaches for community articulation. They first build trust with residents through door-to-door consultations to understand their needs and concerns about waste sorting. Then they foster an intrinsic drive for sustainable waste management, cultivating volunteers who spread the message of waste sorting, recruit participants, and guide correct practices. They also organize activities such as second-hand markets, food composting, community gardens, and sustainable living practices (see Supplementary Table 2), ensuring sustainable, community-driven waste separation.

All 26 ENGOs engage in educating various stakeholders—including the government, schools, the media, and residents—about waste management and waste classification, through outdoor clean-up campaigns, composting workshops, and environmental lectures. Twelve ENGOs (N2, N7-N12, N14, and N18–N21) secured significant government contracts to educate waste separation supervisors who will be responsible for overseeing residents in the waste disposal process.

All of these ENGOs also engage in network-building and emphasize partnerships to address waste management challenges. By creating collaborative platforms, these ENGOs bring together residents, government officials, property management companies, neighborhood committees, community associations, universities, businesses, and other social organizations. This collective network aligns the interests of multiple stakeholders, including technical, academic, and government entities. This approach convinces government officials that ENGO-led sustainability experiments are well-backed by technical expertise and research.

The second primary role of the studied ENGOs involved policy enhancement and advocacy. Interview data indicate that some governments embrace ENGO participation and seek their insights. Twenty-one ENGOs (except N13, N16, N17, N25, and N26) contribute to waste management legislation and policymaking by offering frontline experiences, practices, lessons, demands, and challenges. These ENGOs often have stronger connections with local government compared to the five ENGOs not involved in policymaking.

Moreover, these twenty-one ENGOs complement governmental efforts by promoting public involvement in monitoring waste separation. For example, N6’s snap-and-report initiative encourages citizens to photograph and report waste classification via an app. This crowdsourcing approach, covering over 100 cities in 2022, helps city leaders make informed decisions. They also identify and address deficiencies in waste separation policies, like “inappropriate garbage bin placement, unreasonable garbage transportation pathways, and so on” (N10).

The same twenty-one ENGOs also actively advocate for regional waste classification legislation. A representative of N4 stated:

“We compile frontline experiences and collaborate with local government to create proposals, aiming to advocate for a long-term waste management framework.”

Examples of successful policy advocacy include ENGO-led experiments to gain local political alignment and become a trusted grassroots conduit for waste management. For example, after two years of N19’s work on food waste composting in 25 communities and policy advocacy, Chengyang District in Qingdao introduced a policy offering monetary incentives for adopting composting facilities. This policy provides a one-time reward of 50,000 RMB (7750 USD) and a continuous incentive of 200 RMB (30 USD) per ton of composted food waste.

Of the twenty-one ENGOs contributing to waste management legislation, four (N1, N15, N23, and N24) advocate for policies benefiting the entire ENGO sector. These ENGOs build an evidence base to support the value of ENGOs in community waste management. For example, the Chair of N24, at the 27th UNFCCC Conference (COP 27), highlighted the essential role of ENGOs in community waste management by opening up channels for citizen participation, and enhancing the visibility of Chinese ENGOs in this field46.

The third key role of the studied ENGOs is to pilot waste management models due to their flexibility, innovation, adaptability, and low costs. These “models” refer to the formation of context-specific approaches and social practices that promote and reinforce sustainable daily life patterns47. A representative of N20 stated:

“We dig into the complexities and real needs at grassroots level [and] extract insights to develop the model of community waste management. The government relies on us because they lack [our] extensive understanding of on-the-ground situations.”

In addition to exploring, initiating, and implementing experiments, the ENGOs also aggregate learnings from experiments to foster innovative solutions by documenting and sharing their experience from individual projects through workshops and conferences. Six ENGOs (N1, N8, N15, N21, N23, and N24) aggregate insights from individual projects across various cities and compile them into comprehensive reports, handbooks, toolkits, and guidelines. These resources are produced with the aim of extracting widely applicable models for community waste management, and their dissemination is extensive. For example, N8 developed a replicable and scalable community waste management model from work in 341 communities and published it48. This knowledge is widely distributed among, and replicated by, ENGO partners. From interviews, three ENGOs (N2, N9, and N19) stated that they are learning and implementing the waste management model extracted by N8.

The fourth important role of the examined ENGOs (N1, N15, N23, and N24) is peer-to-peer empowerment. For example, N1 created a collaborative alliance of 43 Chinese waste-management ENGOs, each with specific expertise. This alliance allows ENGOs to cooperate on waste management approaches and action plans, serving as a platform for discussing issues and providing emotional and peer support during challenges.

N24 operates as a funding-oriented ENGO, securing funds for sustainable waste management initiatives by other ENGOs. From 2018 to 2022, N24 invested 8.12 million RMB (1.14 million USD) to support nine ENGOs working in community waste management across eight cities in China49. Similarly, N1, N15, and N23 frequently acquire funding from diverse channels, including governmental bodies and international ENGOs, and allocate a portion to support their peer ENGOs’ efforts.

Six ENGOs (N1, N8, N15, N21, N23, and N24) provide knowledge support to their counterparts in terms of strategic planning and relevant project proposals. N23, for example, focuses on training social workers, offering both knowledge education and practical training to produce skilled workers capable of addressing waste management issues. The guidance and training equip peer ENGOs with essential knowledge and foster camaraderie and trust.

The empowerment also includes connecting peers with essential resources, expertise, and research projects, and assessing and evaluating the efficacy of experiments. For example, N15 supports N19 by facilitating connections with research institutes for food waste composting, regularly visiting community sites to assess progress, and providing timely feedback and guidance.

Challenges faced by 26 ENGOs

In addition to these key roles, the results also reveal the challenges faced by 26 ENGOs. Indicative quotes from interviewees supporting these challenges are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Eighteen ENGOs (e.g., except N6, N7, N8, N14, N15, N18, N23, and N24) report that local governments do not sufficiently recognize or understand their roles in waste management despite central government support (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for government levels overview). The eight ENGOs not reporting this issue are based in economically developed cities like Shenzhen, Xiamen, Suzhou, Beijing, Shanghai, and Fuzhou. In other cities, local governments often award waste management contracts to businesses due to a lack of explicit policy for procuring ENGO services50, as businesses are deemed to offer immediate, visible results, such as smart facilities and technologies, which align with top-down performance assessments10. In contrast, ENGO efforts focus on changing individual behaviors and promoting waste-sorting practices, with less immediate outcomes9, resulting in a reluctance to work with ENGOs and a lack of understanding of their potential. Some local governments even misunderstand ENGO roles, questioning the necessity of funding and viewing them as “cheap labor”, which poses a reputational challenge for these ENGOs.

As shown above, local governments’ recognition of the examined ENGOs varies across cities, and can be influenced by municipal government priorities. For example, while the municipal administrations of Shenzhen, Changsha, Suzhou, Fuzhou, and Xiamen are motivated to promote waste sorting and support ENGOs, the municipal authorities of Zhengzhou and Tianjin show less enthusiasm. Consequently, ENGOs in these two cities face greater challenges in securing recognition and implementing community experiments (see Supplementary Fig. 6).

Local governments’ neglect leads to limited funding for these ENGOs. Even for those ENGOs who may secure government contracts, human resources are not covered, which in turn complicates the execution of labor-intensive tasks, or attracts and retains talents, forcing ENGOs to rely on volunteers. However, high volunteer turnover and difficulty in sustaining participation hinder experimental development.

Unstable funding also hinders investment in professional development, according to the studied ENGOs. Twenty ENGO leaders (except N1, N8, N15, N21, N23, and N24) mentioned lacking the skills and knowledge needed for effective experiment design, implementation, and evaluation.

In cities where local governments collaborate with ENGOs on community waste management, ENGOs still face drawbacks in government service procurement. Two ENGOs (N9 and N18) highlighted challenges such as managing financial accounts, lacking credit access within the banking system, and paying higher taxes than corporations. Consequently, they are considering transitioning from a non-profit structure to registering as businesses.

ENGOs in Shenzhen face unique challenges due to the city’s relatively young status and underdeveloped community government system, which can be an important source of grassroots authority, influence, and support that are needed to effectively implement their initiatives.

Four ENGOs (N1, N15, N23, and N24) focus on platform building and peer support and cited the difficulty in finding passionate and dedicated partners for cooperation.

Discussion

Our analysis shows that ENGOs’ roles vary across different operational levels due to their distinct competencies and remits. A clear classification of these levels is essential for policymakers and practitioners to monitor and support transitions by addressing role gaps at different operational levels32. We propose these different operational levels can be considered as actor niches, where ENGOs operate with diverse priorities51,52, funding, ownership, governance, and scope of action, leading to different approaches and impacts in sustainability experimentation32,53. There are three types of actor niches:

-

Local actor niche (representatives: N13, N16, N17, N25, and N26): these ENGOs primarily focus on localized perspectives and address specific community waste issues. Their activities include raising awareness, sharing knowledge, building capacities, and establishing networks within their local areas at a community level.

-

Inter-local actor niche (representatives: N2–N7, N9–N12, N14, N18–N20, and N22): these ENGOs primarily coordinate stakeholders and facilitate dialogs across various fields. They aggregate learning and enhance policy advocacy by providing the government with on-the-ground experiences at a regional level.

-

Trans-local actor niche (representatives: N1, N8, N15, N21, N23, and N24): these ENGOs support and empower peer organizations, establish institutional spaces, catalyze political change, create and circulate consolidated knowledge and models on community waste management at a national level.

The descriptions of ENGOs’ roles in each niche are not exclusive but highlight their main functions. Across different actor niches, ENGOs have formed equitable and collaborative partnerships, enhancing their influence by combining capabilities. Through cross-pollination of ideas and practices, the diverse ENGOs in China’s waste management sector foster a comprehensive approach, enabling locally adapted interventions and broad-based change through advocacy and policy engagement. This section provides detailed discussions on the roles of ENGOs at local, inter-local, and trans-local actor niches. At the local level, ENGOs are a key force in articulating community needs and building long-term trust with residents. At inter-local and trans-local actor niches, ENGOs test policies, provide feedback to policymakers to enhance policies, generate new waste management practices through knowledge generation and aggregation, and empower peers. Additionally, the evolving nature of their roles and actor niches is explored.

The studied ENGOs at local and inter-local actor niches act as supportive partners to government efforts in waste management, especially when central policies are handed down to lower administrative levels lacking the expertise and capacity to engage communities26. Government-led mobilization often focuses on installing hardware rather than changing daily routines, which is essential for successful waste separation and recycling54. Obtaining widespread support and cooperation from residents and enhancing long-term trust and cooperation requires network-building and continued information-sharing throughout the stakeholder network55. Local officials often lack the expertise, resources, or political leeway to conduct community research or experiments, creating opportunities for ENGOs. ENGOs at the local and inter-local actor niches focus on vision articulation by circulating information, raising awareness, establishing networks, and building capacities among participants. Individuals involved in these ENGOs exhibit a strong dedication to environmental sustainability56, which fosters public engagement and motivates individuals, as the public tends to trust ENGOs more56,57. Thus, ENGOs at the local and inter-local actor niches play a crucial role in addressing bureaucratic inexperience in waste management.

Government and ENGO interviewees agreed that local government agencies often lack expertise in social programs and rely on ENGOs for successful initiative development. One of the key motivations of local officials in solving challenges is to win promotions, but innovation may carry political risks. Collaborating with ENGOs allows officials to avoid the risk of failure while gaining credit for successful innovations. A common phenomenon is that if a policy implemented by ENGOs succeeds, officials claim success; if it fails, the ENGOs bear the consequences in China58.

Waste-sorting policies and socio-economic contexts vary significantly across China’s cities and regions. Community size, settings, cohesion, and governance impact the effectiveness of waste sorting59. ENGOs at the inter-local and trans-local actor niches focus on testing new approaches, developing models, and aggregating knowledge and resources from various experiments across different regions to address demands beyond local contexts. These waste management models have great potential to form effective waste classification approaches tailored to local needs.

ENGOs at the inter-local and trans-local actor niches also aim to demonstrate pilot waste management solutions for government adoption and dissemination. Research has found that Chinese ENGOs often establish effective models for social problems and then persuade state agencies to implement them on a larger scale60. Many innovations described by officials were initially piloted and promoted by grassroots ENGOs.

The studied ENGOs at the inter-local and trans-local actor niches play an important role in policy enhancement, offering policymakers valuable insights and recommendations based on front-line experiences. They provide ongoing access to on-site information, knowledge, and cooperation among residents, which is crucial for developing effective waste separation strategies and policies55.

Six ENGOs at the trans-local actor niche mobilize political support for grassroots endeavors and build evidence to validate community waste management experiments. They influence policymaking by aggregating innovations and enhancing the visibility and impact of their experiments through public debates and media campaigns. These ENGOs introduce a new environmental discourse centered on civic participation, acting as facilitators of citizen engagement in participatory governance61,62. They serve as knowledge brokers, supporting dialog between the government and citizens by conveying policies to citizens and citizens’ preferences to decision-makers63,64. Thus, their efforts open channels for citizen participation in political processes, potentially shaping Chinese politics over time. By addressing environmental problems through non-confrontational, boundary-spanning, or legal actions, these ENGOs may gradually push the boundaries of institutional and governance structure and change the relationship between the state, citizens, and non-state organizations. They provide channels for inclusive dialog and alternative solutions, especially where democratic institutions are weak or inadequate65.

Six ENGOs are identified as working in the trans-local actor niche, engaging in peer empowerment, and serving as enablers and promoters of fellow ENGO partners to conduct experiments in different regions in China. These trans-local ENGOs provide crucial support, including financial and informational aid, which creates favorable conditions for local and inter-local ENGOs. This support allows local and inter-local ENGOs to explore and develop waste management approaches tailored to specific local and regional needs. By fostering a collaborative environment, these trans-local ENGOs enhance the capacity of partners to innovate and implement sustainable waste management practices across diverse communities.

It is important to note that roles are not identically and uniformly adopted by ENGOs at various actor niches. Influenced by their own interests, priorities, capabilities, and external contextual factors, the role of ENGOs can remain unchanged or evolve.

Five ENGOs (N13, N16, N17, N25, and N26) have unchanged roles, focusing primarily on vision articulation at the local actor niche. Each has fewer than five full-time staff and is deeply rooted in its community, acquiring place-specific knowledge. Their experiments involve few actors, and their networks are dispersed with limited connectivity.

Fifteen ENGOs (N2–N7, N9–N12, N14, N18–N20, and N22) have expanded their roles from local to inter-local actor niches over time. Two ENGOs (N8 and N21) have undergone the most extensive role expansion, embracing policy advocacy and policy enhancement, and peer-to-peer support, pushing the boundaries of their traditional roles and nearing the trans-local actor niche. Four ENGOs (N1, N15, N23, and N24) have maintained their roles in the trans-local niche unchanged over time.

Changes in ENGO roles are influenced by internal competition and the evolving needs of stakeholders32,66. Our analysis suggests that the factors driving the role expansion and changes in ENGOs’ actor niches align with those contributing to the successful scaling up and diffusion of ENGO-led experiments. Some ENGOs (i.e., N13, N25, and N26) encounter challenges in expanding or scaling up their experiments, while others (i.e., N16 and N17) may not wish to develop or diffuse their experiments. As a result, they have fewer roles and limited influence. This aligns with existing literature, which indicates that the decision to expand and scale up an experiment depends on factors such as leader ambition, resources, and the external environment67.

Leadership is crucial in managing stakeholder expectations and fostering the growth of experiments68. Positive relationships with multiple stakeholders enable ENGOs to access new resources, increase visibility, and enhance professional capacities69. Additionally, peer learning within intra-organizational networks helps develop shared objectives and a common understanding among ENGOs44. These networks facilitate collaboration, support lobbying efforts, promote knowledge sharing of best practices, and contribute to the institutionalization of learning67. These factors contribute to accumulating resources, expanding actor networks, and social and institutional influence of ENGO experimentation, which may consequently expand their functions.

Another critical factor for role expansion is the presence of favorable political, institutional, economic, and cultural settings. For example, two ENGOs (N8 and N21) evolved significantly from local to trans-local niches because, when the waste-sorting policy was introduced in their regions, these ENGOs secured more government contracts and resources, expanding their influence. This finding aligns with existing literature on the fluctuating nature of the ENGO’s roles27, while deepening the understanding of the underlying rationales of such evolution.

To summarize, this research examined the roles and challenges of ENGOs in Chinese community waste management drawing on data from 106 Chinese ENGO surveys and 26 in-depth case studies. We identified four main roles: vision articulation, model development, policy advocacy and enhancement, and peer empowerment. These roles are adopted across three operational levels, which we conceptualized as local, inter-local, and trans-local actor niches, each defined by their specific capacities, priorities, goals, ideologies, and mandates. Some ENGOs address localized waste problems, articulate the needs of various stakeholders, and build partnerships at local and inter-local actor niches. Others develop waste management models and advocate for policy changes at regional and national levels within inter-local and trans-local actor niches. Additionally, some ENGOs empower peers, create standards, and drive sector-wide political change in the trans-local actor niche. While our findings indicate that the actor niches and roles of ENGOs may remain consistent or evolve based on their interests, capabilities, and external contextual factors, their efforts across these actor niches collectively contribute to sustainable waste management transitions in China.

Despite their essential roles in promoting effective community waste management approaches in China, ENGOs face challenges such as securing local government recognition, stable funding, human resources, and professional development. Our findings suggest three key policy implications. Firstly, strengthening government-ENGO linkages is important to better harness ENGOs’ resources, strategies, and capabilities, fostering political will for embracing bottom-up approaches. Secondly, institutionalizing or strengthening the legal status of ENGOs may provide clarity and legitimacy to their contributions, especially given the lukewarm engagement from municipal government officials in some cities. Thirdly, the professional development of ENGOs is crucial for improving waste-specific knowledge, engaging residents, extracting learning, transferring knowledge, and increasing their visibility.

Our findings show that ENGOs across different actor niches have great potential to contribute to waste management, which policymakers can tap into. Further research is needed to explore the long-term effects of ENGO experiments, strategies for scaling successful ENGO-led experiments, and expanding their roles and influences. Enhancing our understanding in these areas will better support ENGOs in delivering sustainable community waste management transitions in China.

Methods

Data collection

We adopted a mixed-method approach for collecting primary data on ENGO roles and challenges in participating in Chinese community waste management, combining participatory observation, surveys, elite interviewing, and documentary analysis. The main author participated in conferences, workshops, and events related to ENGO-led community waste management in various cities across China from 2020 to 2022. This active engagement facilitated the development of a comprehensive understanding of typical ENGOs working in the field of waste separation in China, which have been operational for over one year (at the time of conducting the research) and have garnered interest and emulation in their respective regions and beyond.

We designed survey questions based on existing literature on ENGO roles34,36,39and challenges38,68,70, two relevant reports71,72, and consultations with experienced ENGO leaders. We conducted online surveys between April and June 2022 using the Wenjuanxing tool with the support of N15 (see Supplementary Note 2). One hundred six ENGOs participated and answered multiple-choice questions about their focus areas, geographical distribution, scales, funding resources, roles, and challenges. Open-ended questions were included to explore additional nuanced roles and challenges of ENGOs not covered in existing literature.

We selected 26 ENGOs from the initial pool of 106 ENGOs for further interviews based on three key factors: (1) a significant role in directing the development of community waste management experiments, (2) availability of written reports or project websites for in-depth analysis of the ENGOs’ roles in initiating and implementing experiments, and (3) willingness of the founders or senior staff to participate in our study.

We conducted qualitative case studies for each of the 26 selected ENGOs (see Table 1), gathering insights through in-depth semi-structured interviews with one to four elite informants, such as founders or senior staff members. The interviews were conducted both online and in-person, with 11 site visits conducted in 2022. Due to COVID-19 restrictions in China, site visits were not possible for the remaining 15 cases. However, self-published reports or project websites of each case study were available.

The data set is supplemented by secondary data used including government policy documents, media reports, academic papers, and ENGO-produced project reports accessed through websites and academic journals.

Data analysis

We employed both qualitative and quantitative data analysis. First, we analyzed survey data. For multiple-choice questions, we used statistical description and visualized in Microsoft Excel the broader information of waste management ENGOs and patterns of ENGO roles and challenges. We manually coded responses to open-ended questions using NVivo 12 software to understand participants’ comments on their roles and challenges beyond the options provided in the multiple-choice questions.

We translated interview transcripts from Chinese to English and manually coded and analyzed them using NVivo 12 software in three stages. First, we employed an inductive coding approach. At this stage, the coding was done without a set of codes defined by theory as a point of departure, and we attempted to search for patterns and potential categories that serve as a coding structure. 138 codes related to ENGO roles and 10 codes of challenges were obtained from this stage. Then we employed a deductive coding approach. At this stage, we derived a coding scheme based on literature and categorized the codes obtained from the first stage. This led us to obtain 32 codes for ENGO roles and 8 codes for their challenges. Finally, we adopted an iterative abductive approach to coding73. We iterated between data, emerging patterns, and existing literature, to develop a coding scheme (see Supplementary Fig. 7). This process enabled us to identify ENGO roles (Fig. 3) and the four main categories of roles (Fig. 4).

A major limitation of this study is the absence of up-to-date and comprehensive data on the total number of ENGOs actively participating in community waste management in China. This makes it difficult to determine the proportion surveyed ENGOs represent of similar entities. The representativeness of survey and interview results is another limitation stemming from the absence of data on the total population of ENGOs involved in community waste management. We cannot know whether the surveyed and interviewed ENGOs adequately represent the diverse range of organizations’ roles in this field. To address these limitations, future research should focus on collecting comprehensive data, enabling a more robust assessment.

Responses