Cd248a regulates pericyte development and viability in zebrafish

Introduction

Pericytes, recognized as vascular mural cells embedded within the basement membrane of capillaries, play crucial roles in regulating blood flow, stabilizing capillary structures, and maintaining the integrity of the blood–brain barrier (BBB)1,2. The loss or dysfunction of pericytes leads to the development and progression of various diseases, such as diabetes3,4, Alzheimer’s disease5, stroke6, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis7 and aging8.

In the past decade, several analyses have revealed the basic molecular mechanisms regulating pericyte development, including PDGFRβ signaling9, Notch signaling10, TGFβ/BMP signaling11 and sonic hedgehog signaling12. However, given the heterogeneity of pericyte transcription profiles and spatial distribution, it is necessary to identify candidate gene functions for pericyte development. This will enhance our understanding of the pathogenesis of diseases related to pericyte disorders and provide insights for future therapeutic approaches.

CD248, also known as tumor endothelial marker 1 or endosialin, is a type I single transmembrane glycoprotein. It serves as a pericyte marker during embryonic and tumor neovascularization, being highly expressed by pericytes and fibroblasts in developing embryos and tumors undergoing active physiological or pathological angiogenesis, but weakly expressed in normal adult tissues13,14. Both types of angiogenesis are largely induced by the hypoxic microenvironment, and further studies have confirmed that CD248 transcription is regulated by HIF-215. CD248-deficient mice exhibit fully developed and functional vasculature and normal wound healing16. However, other studies have shown that CD248 can enhance wound healing by interacting with PDGFR17. Moreover, a defect in selective vessel regression leading to increased vessel density was observed in CD248 knockout mice in a postnatal retina model18. In contrast, tumor volume and density of vessels and pericyte density are lower in orthotopic lung cancer-transplanted mice lacking CD24819. These contrasting results may be related to the functional heterogeneity of CD248 in different organs. Additionally, CD248 is significantly increased in liver injury and can regulate hepatic stellate cell proliferation in response to PDGF-BB stimulation20. CD248 is also required for complete popliteal lymph node expansion and subsequent immune responses21. Recently, zebrafish-deficient models of cd248a and cd248b (orthologs of human CD248) were reported, and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines was downregulated when the zebrafish were treated with LPS in their deficient model22.

Despite significant advancements in understanding the role of CD248 in various physiological and pathological processes, the specific role and molecular mechanisms of CD248 in pericyte proliferation and survival remain undefined. The zebrafish model offers advantages in visualizing vascular development using fluorescently labeled pericyte reporter lines, providing an excellent opportunity to explore the roles of cd248 in regulating pericyte proliferation and apoptosis. In this study, we examined the expression patterns of two cd248 paralogs (a and b) in zebrafish and generated mutants via CRISPR/Cas9 to determine whether cd248a or cd248b mutation affects pericyte proliferation and apoptosis. Our results suggest that cd248a deficiency reduces pericyte number by regulating Pdgfrβ function during embryonic development and increases pericyte apoptosis induced by hypoxia in zebrafish larvae. Our newly established zebrafish mutant lines and related studies will help us elucidate the molecular mechanism of the effects of the cd248a and cd248b genes on pericyte function.

Results

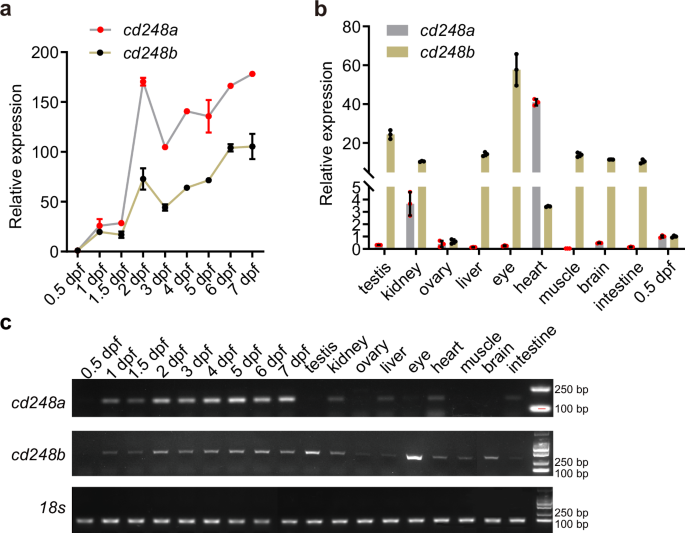

Temporal and spatial gene expression profiles of cd248a and cd248b

It has been reported that human CD248 is primarily expressed in developing embryos but is weakly expressed in normal adult tissues. We wondered whether the zebrafish paralogs, cd248a and cd248b, exhibit similar expression patterns. We investigated the expression levels of cd248a and cd248b at various embryonic stages and in different adult zebrafish organs using qPCR. As shown in Fig. 1a, both genes displayed almost consistent expression trends during embryonic development. Their expression levels gradually increased from 0.5 dpf to 7 dpf, with a sharp rise at 2 dpf and a slight decrease at 3 dpf. Moreover, the expression level of cd248a was significantly higher than that of cd248b at the same developmental stage. In adult fish, the expression of cd248a was extremely low in most organs, except for the heart and kidney, and was much lower in adult fish compared to embryos at 0.5 dpf. In contrast, cd248b was expressed at high levels in organs other than the ovary (Fig. 1b). To directly compare the expression levels of cd248a and cd248b in embryonic and adult organs, we performed semiquantitative RT-PCR. The results were consistent with the qPCR results (Fig. 1c).

Relative expression levels of cd248a and cd248b at different developmental stages (a) and in various adult zebrafish tissues (b). Gene expression values were normalized to the level at 0.5 dpf (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). c Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression for cd248a and cd248b at different developmental stages and in different adult zebrafish tissues. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

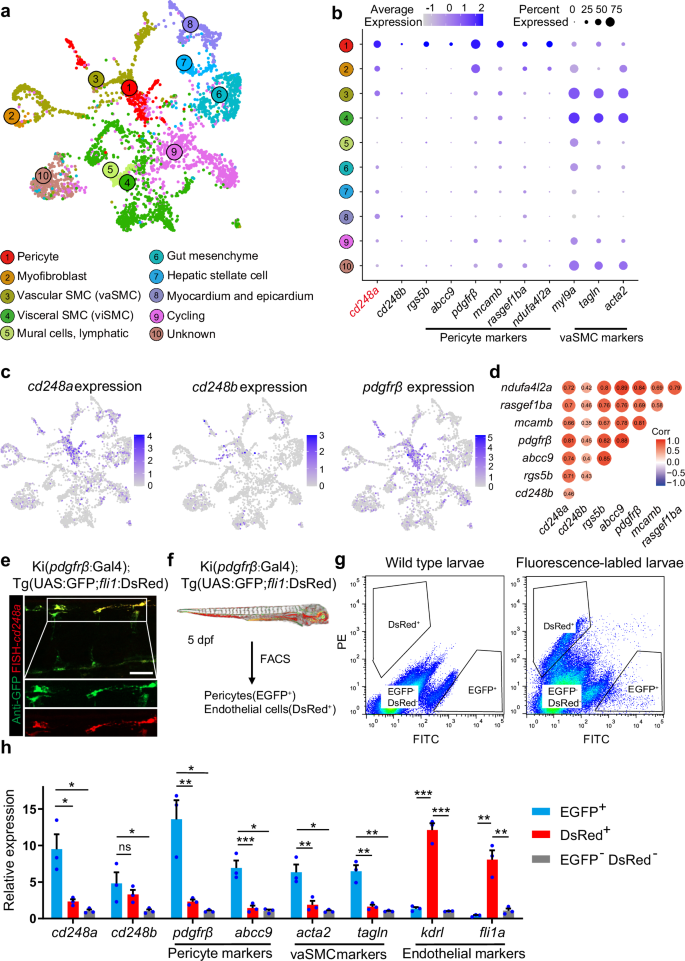

cd248a is highly expressed in most pericytes during embryonic development

To identify the cell populations that express cd248a and cd248b, we analyzed published single-cell sequencing data from different developmental stages in zebrafish (14–120 hpf)23. The distributions of nonskeletal muscle subclusters were superimposed on the temporally coded UMAP (Fig. 2a). We then constructed UMAP plots of genes associated with pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells (vaSMCs) (Fig. 2b, c, Supplementary Fig. 1). Our results showed that cd248a is highly expressed in pericytes, consistent with the expression of pdgfrβ, the most specific and reliable vascular mural cell marker. In contrast, cd248b is expressed in only a very small proportion of pericytes. We also found that cd248a correlates most highly with pdgfrß (Fig. 2d) and indeed, cd248a is expressed in the majority of pdgfrß+ cells (Fig. 2e).

a Using publicly available single-cell sequencing data set (GSE223922), we show a UMAP projection of 3866 non-skeletal muscle cells collected from whole zebrafish embryos at 50 different developmental stages between 14 and 120 hpf. b Dot plots showing the expression of cd248a, cd248b, and selected pericyte and vascular smooth muscle cell (vaSMC) markers in the indicated clusters. The size of the dot corresponds to the percentage of cluster cells expressing the indicated gene. Color intensity reflects the relative mean expression per cell. c UMAP plots of gene expression (blue dots) highlight individual cells that express cd248a, cd248b, and pdgfrβ. Darker blue dots indicate higher gene expression, while gray dots indicate no gene expression. d Correlation analysis of cd248a, cd248b and other pericyte marker genes. e Labeling of FISH-cd248a (shown in red) and anti-GFP (shown in green) in the Tg(pdgfrβ:Gal4; UAS:GFP) larvae at 4 dpf. Scale bars = 50 μm. f Schematic of the experimental design for sorting pericytes and endothelial cells. g Graphed data of representative FACS analysis of EGFP+ and DsRed+ cells from dissociated 5 dpf Tg(pdgfrβ:Gal4; UAS:GFP; fli1:DsRed) larvae. h qRT-PCR analyses of cd248a, cd248b, pericyte marker genes (pdgfrβ and abcc9), vaSMC marker genes (acta2 and tagln) and endothelial cell marker genes (kdrl and fli1a) followed FACS sorting of EGFP+, DsRed+ and double-negative cells. Data were analyzed by One-way ANOVA and presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). *, p < 0.05. **, p < 0.01. ***, p < 0.001. ns: no significance.

To confirm the expression of cd248 isoforms in zebrafish pericytes, we sorted endothelial cells and pericytes via FACS from zebrafish embryos with Ki(pdgfrβ: Gal4) and Tg(UAS:GFP; fli1:DsRed) transgenic backgrounds, which expressed GFP and DsRed in pericytes and endothelial cells, respectively (Fig. 2f, g). The expression levels of cd248a and cd248b in these two distinct cell populations were analyzed via qPCR. The results revealed that both cd248a and cd248b were expressed in pericytes; but the expression of cd248a was higher than that of cd248b (Fig. 2h). Moreover, we obtained similar results by analyzing publicly available transcriptomics data comparing pdgfrβ+ vs. pdgfrβ– cells24 and acta2+ vs. acta2– cells25 in zebrafish (Supplementary Fig. 2). Taken together, these data strongly support that cd248a is an ideal pericyte marker gene during embryonic development.

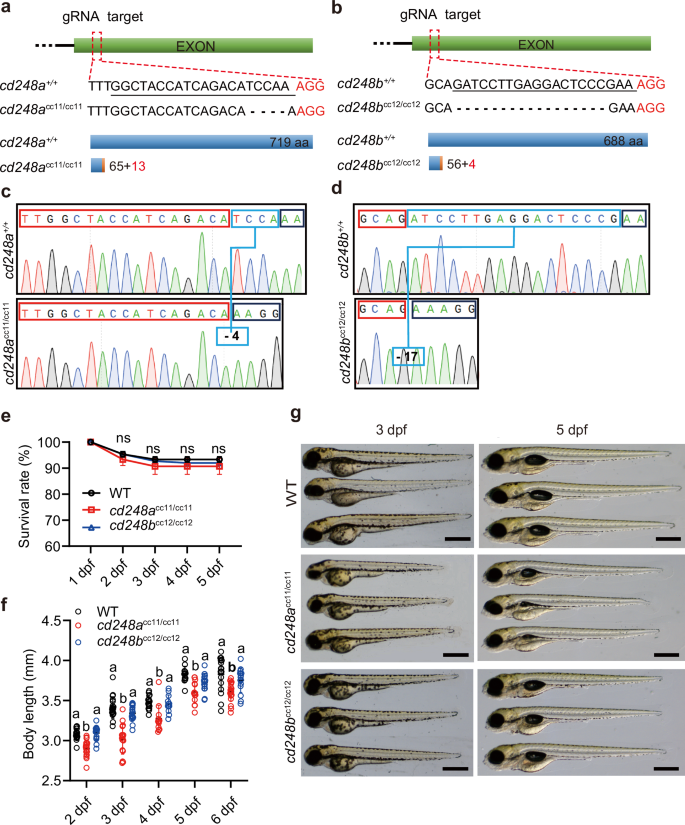

cd248a mutant zebrafish exhibits a deficit of pericytes

To examine whether cd248a and cd248b are important for pericyte development, we employed the CRISPR/Cas9 technique to generate mutants in zebrafish. Both cd248a and cd248b consist of a single exon, and we targeted the region near the N-terminus for mutagenesis. We successfully identified and confirmed cd248a and cd248b mutants with 4 bp and 17 bp deletions, respectively, through sequence analysis (Fig. 3a-d). These mutant zebrafish lines were registered with ZFIN under the designations cd248acc11/cc11 and cd248bcc12/cc12, respectively. We compared the survival rates of these mutant lines with the WT fish from 1 to 5 dpf and found no significant difference (Fig. 3e). Additionally, we tracked and compared the average body length of the mutants with the WT from 2 to 6 dpf (Fig. 3f) and provided representative images of larvae at 3 dpf and 5 dpf (Fig. 3g). While cd248acc11/cc11 and cd248bcc12/cc12 larvae appeared largely similar to wild type, the cd248acc11/cc11 larvae exhibited delayed growth and impaired swim bladder development. These findings suggest that although overall development is not severely disrupted in the mutants, specific aspects such as pericyte development and related physiological processes may be compromised in cd248a mutants.

Diagrams depicting the complete gene structures and deletion mutants of cd248a (a) and cd248b (b). The sgRNA target sequence is underlined. The wild-type Cd248a protein consists of 719 amino acids; the Cd248a mutant (cd248acc11/cc11) consists of only 65 amino acids identical to the wild type and 13 frameshifted amino acids. The wild type Cd248b protein consists of 668 amino acids; the Cd248b mutant (cd248bcc12/cc12) consists of only 56 amino acids identical to wild type and 4 frameshifted amino acids. Sequencing analysis shows indels sites in cd248acc11/cc11 (c) and cd248bcc12/cc12 (d), indicated with the blue box. e Survival rate of cd248acc11/cc11, cd248bcc12/cc12 and wild type zebrafish from 1 to 5 dpf (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). f Body length of cd248acc11/cc11, cd248bcc12/cc12 and wild-type zebrafish from 2 to 6 dpf (n ≥ 12 embryos or larvae). g Representative images of cd248acc11/cc11, cd248bcc12/cc12 and wild-type larvae at 3 dpf and 5 dpf. Scale bars = 500 μm. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA and presented as mean ± SD. ns: no significance. Different alphabets (a and b) between groups indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

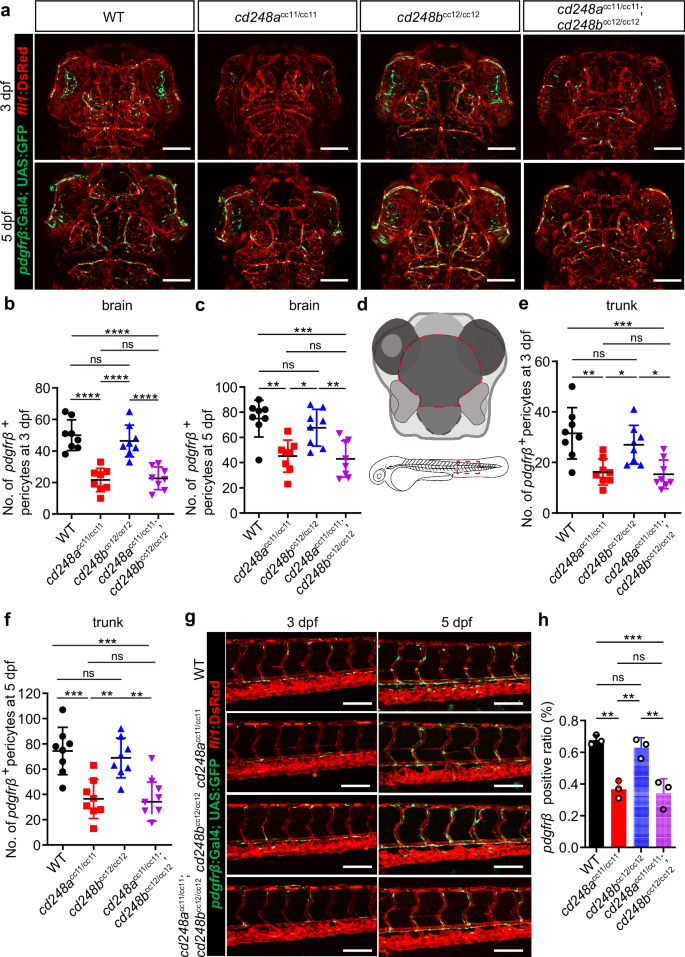

We crossed both mutant lines with the Ki(pdgfrβ:Gal4) and Tg(UAS:GFP; fli1:DsRed) lines to investigate pericyte development by examining and counting the number of pdgfrβ+ pericytes. At 3 and 5 dpf, the number of pdgfrβ+ pericytes in cd248a mutant and double mutant larvae was significantly lower than that in wild-type larvae both in the brain (Fig. 4a-d) and trunk (Fig. 4d-g). In contrast, no significant differences were detected in cd248b mutant larvae (Fig. 4a-g). To validate this pericyte deficiency, we determined the pdgfrβ-positive ratio in 5 dpf larvae using FCAS. The results corroborated the findings from the above confocal analyses (Fig. 4h).

Confocal micrograph (a) and quantification of pdgfrβ+ brain pericytes at 3 dpf (b) and 5 dpf (c) in wild-type (WT) and mutant zebrafish (n = 8 embryos or larvae). Scale bars = 100 μm. d Schematic diagram of the counting region, as circled by the red dashed lines. Confocal micrograph (g) and quantification of pdgfrβ+ pericytes in the trunk region at 3 dpf (e) and 5 dpf (f) in wild-type (WT) and mutant zebrafish (n = 8 embryos or larvae). Scale bars = 100 μm. h FACS analysis of the proportion of pdgfrβ+ cells in wild-type and mutant fishes (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). Data were analyzed by One-way ANOVA and presented as mean ± SD. *, p < 0.05. **, p < 0.01. ***, p < 0.001.****, p < 0.0001. ns: no significance.

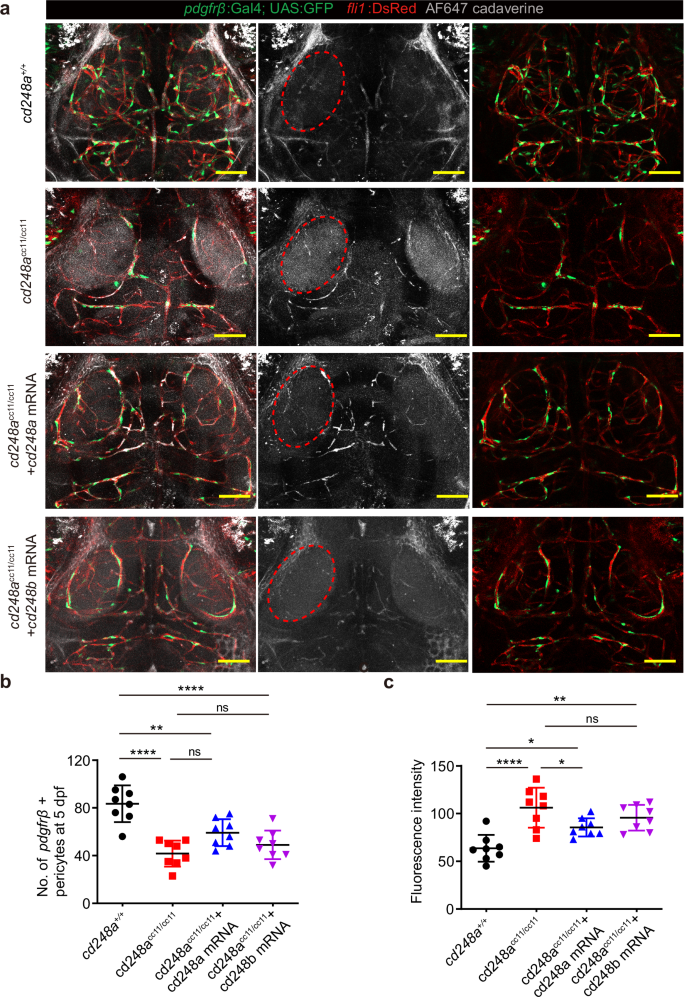

The defective BBB in cd248a

cc11/cc11 zebrafish can be partially rescued by injecting cd248a mRNA

Pericytes are crucial for regulating BBB integrity, and their deficiency can increase BBB permeability. To determine whether the defective BBB is due to impaired pericyte coverage resulting from the loss of cd248a function, we conducted a dye diffusion assay using Alexa FluorTM-647 cadaverine (1 kDa, 0.5 mg/ml). This assay visualizes and quantifies vascular leakage by measuring the fluorescence intensity of cadaverine in the extravascular space. Our data showed significantly increased vascular permeability in cd248acc11/cc11 zebrafish compared to cd248a+/+ controls (Fig. 5a). To confirm that the increased permeability was indeed caused by cd248a deficiency, we performed a rescue experiment by injecting in vitro synthesized cd248a or cd248b mRNA into zebrafish eggs. The results indicated that only cd248a mRNA, but not cd248b mRNA, could partially restore the phenotype of cd248a mutant larvae (Fig. 5a-c).

a Cerebrovascular images showing infiltration of cadaverine in the extravascular space, as indicated by red circle. Scale bar = 50 μm. b Quantification of pdgfrβ+ brain pericytes in cd248a+/+ and cd248acc11/cc11 larvae with or without mRNA injection (n = 8 larvae). c Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity within the red circle area (n = 8 larvae). Data were analyzed by One-way ANOVA and presented as mean ± SD. *, p < 0.05. **, p < 0.01. ****, p < 0.0001. ns: no significance.

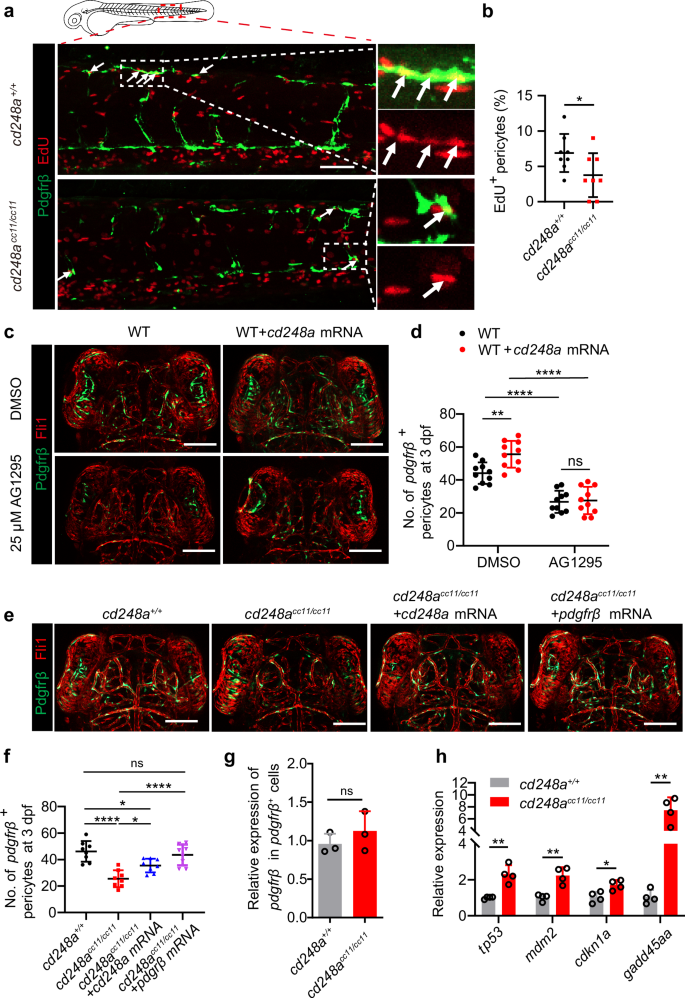

Cd248a regulates pericyte proliferation and functions through Pdgfrβ

To investigate whether the increase in pericyte number was due to pericyte proliferation regulated by cd248a, EdU staining was used to label proliferating pericytes26. Compared with cd248a+/+ larvae, cd248acc11/cc11 zebrafish larvae exhibited significantly fewer pericytes, and the percentage of EdU+ pericytes (defined as the number of pdgfrβ+ EdU+ pericytes divided by the total number of pdgfrβ+ pericytes) was significantly lower (Fig. 6a, b). Overexpression of cd248a increased the number of pdgfrβ+ pericytes in cd248a+/+ larvae (Fig. 6c, d, Supplementary Fig. 3a), and restored the pericyte deficiency phenotype in cd248acc11/cc11 larvae in both the brain and trunk (Fig. 6e, f, Supplementary Fig. 3b). These results indicate that cd248a functions in regulating pericyte proliferation.

a Confocal micrograph showing pericytes (pdgfrβ+ cells, green) and EdU staining (red) in cd248a+/+ and cd248acc11/cc11 larvae. Arrows indicate EdU-positive pericytes. Scale bar = 50 μm. b Quantification of the percentage of EdU-positive pericytes at 3 dpf, represented as the ratio of the number of EdU-positive pericytes to the total number of pericytes within the imaging area (n = 8 embryos). Confocal micrograph (c) and quantification (d) of brain pericytes at 3 dpf in WT and cd248a-overexpressing groups with or without exposure to AG1295 (n = 10 embryos). Scale bar = 100 μm. Confocal micrograph (e) and quantification (f) of brain pericytes at 3 dpf in cd248a+/+ and cd248acc11/cc11 groups with or without mRNA injection (n = 8 embryos). Scale bar = 100 μm. g Relative expression levels of pdgfrβ in pdgfrβ+ cells isolated from cd248a+/+ and cd248acc11/cc11 larvae (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). h Relative expression levels of cell cycle arrest-related genes in pericytes isolated from cd248a+/+ and cd248acc11/cc11 larvae (n = 4 biologically independent experiments). Data in all quantitative panels are presented as mean ± SD; two-tailed unpaired t test (b, g, h), one-way ANOVA (f) and two-way ANOVA (d). *, p < 0.05. **, p < 0.01. ****, p < 0.0001. ns: no significance.

Previous data have shown that CD248 is involved in hepatic stellate cell proliferation induced by PDGF-BB stimulation20 and that Pdgfb/Pdgfrβ signaling is crucial for zebrafish pericyte proliferation27, suggesting that cd248a may regulate pericyte proliferation, at least in part, by regulating Pdgfrβ function. To test this hypothesis, zebrafish embryos were treated with the PDGFRβ inhibitor AG1295, a blocker of mural cell proliferation10,28. Figure 6c and d shows that the increase in pericytes caused by overexpression of cd248a did not occur when larvae were treated with 25 μM AG1295. Additionally, Overexpressing pdgfrβ could restore the pericyte deficiency in cd248acc11/cc11 larvae (Fig. 6e, f, Supplementary Fig. 3b). These results indicate that the regulation of pericyte proliferation by cd248a is dependent on the function of Pdgfrβ.

Furthermore, no transcriptional changes in pdgfrβ were detected in pdgfrβ+ pericytes sorted from cd248acc11/cc11 zebrafish larvae compared with those sorted from cd248a+/+ larvae (Fig. 6g). This suggests that the increase in pericyte number regulated by cd248a requires Pdgfrβ function through a non-transcriptional mechanism. It has been reported that activation of the PDGF/PDGFR signaling pathway is associated with cell proliferation through modulation of PI3K/Akt pathway, which in turn regulates p53, leading to cell cycle arrest29,30,31. We investigated the expression levels of cell cycle arrest-related genes26 (tp53, cdkn1a, mdm2, and gadd45aa), and the results showed that these genes were all upregulated in cd248acc11/cc11 larvae (Fig. 6h). This implies that the decrease in pericytes is at least partially related to cell cycle arrest.

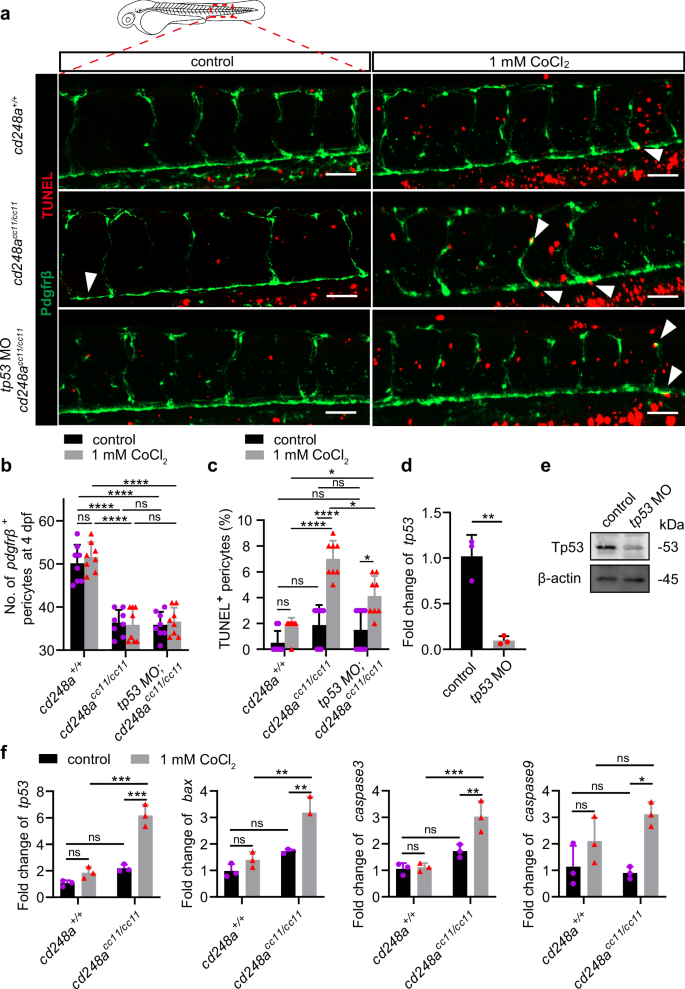

Deletion of cd248a increases hypoxia-induced apoptosis of pericytes

Previous studies have emphasized that the transcription of CD248 is regulated by a hypoxic microenvironment, which tends to induce apoptosis in most cells15,32. However, it remains unclear whether increased expression of CD248 plays a role in resisting apoptosis in pericytes. To investigate this, CoCl2, a classic hypoxia inducer, was applied to induce hypoxic conditions33.

The expression levels of cd248a and cd248b were examined in 5 dpf larvae and in different adult zebrafish organs. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a, b, an increase in cd248a expression was detected both at the juvenile stage and in various organs of the adult fish (except for the heart and muscle) after CoCl2 treatment. In contrast, elevated cd248b expression was detected only in the ovary, brain, eye, and intestine (Supplementary Fig. 4c). These results indicate that the hypoxia-induced expression of cd248a in zebrafish is similar to that of human CD248. Thus, we explored the potential antiapoptotic effect of CD248 using cd248a mutant model.

To determine whether enhanced cd248a expression confers resistance to CoCl₂-induced apoptosis in pericytes and whether this resistance is mediated by a tp53-dependent apoptotic response, a tp53 morpholino (MO)34 was injected into cd248acc11/cc11 eggs to block the translation of Tp53. TUNEL staining was then performed on 4 dpf larvae exposed to CoCl₂ for 24 h. As expected, the number of apoptotic pericytes significantly increased in cd248acc11/cc11 larvae after exposure to CoCl₂, but only slightly increased in cd248a+/+ larvae. Knockdown of tp53 rescued the pericyte apoptotic phenotype (Fig. 7a-c). Notably, cd248acc11/cc11 larvae had significantly more apoptotic pericytes than wild-type larvae even without exposure to CoCl₂ (Fig. 7a-c). These data indicate that cd248a deficiency increases hypoxia-induced pericyte apoptosis through a tp53-dependent apoptotic response.

a Confocal micrograph showing pericytes (pdgfrβ+ cells, green) and TUNEL staining (red) in WT and cd248acc11/cc11 larvae with or without tp53 MO injection at 4 dpf. Arrows indicate TUNEL-positive pericytes. Scale bar = 50 μm. b Quantification of pericyte numbers in WT and cd248acc11/cc11 larvae with or without tp53 MO injection at 4 dpf within the imaging area (n = 8 larvae). c Quantification of the percentage of TUNEL-positive pericytes at 4 dpf represented as a ratio of the TUNEL-positive pericyte to the total number of pericytes within the imaging area (n = 8 larvae). The effectiveness of the tp53 MO in blocking transcription (d) and translation (e) (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). f Relative expression levels of apoptosis-related genes in pericytes isolated from cd248a+/+ and cd248acc11/cc11 larvae with or without exposure to CoCl₂ (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). Data in all quantitative panels are presented as mean ± SD; two-tailed unpaired t test (d), and two-way ANOVA (b, c and f). *, p < 0.05. **, p < 0.01. ***, p < 0.001. ****, p < 0.0001. ns: no significance.

To confirm the protective effect of cd248a on pericytes against hypoxia-induced apoptosis, the expression levels of several apoptosis-related genes35 were analyzed in pdgfrβ+ pericytes sorted from cd248a+/+ or cd248acc11/cc11 larvae treated with or without CoCl₂. Consistent with the TUNEL results, exposure to CoCl₂ led to a significant increase in the expression of caspase3, caspase9, tp53, and bax in cd248a-deficient larvae compared to the wild-type group. (Fig. 7f). Overall, these data suggest that cd248a alleviates hypoxia-induced pericyte apoptosis by regulating the expression of genes related to the tp53-mediated apoptotic signaling pathway.

Discussion

CD248 is a cell membrane protein that is highly expressed in pericytes and fibroblasts during embryogenesis and tumorigenesis. Although CD248 has been extensively studied for its role in tumor neovascularization13, vessel regression18, wound healing17, chronic liver injury20, renal fibrosis36, and other diseases37,38, little is known about its role in regulating pericyte proliferation and survival. The zebrafish embryo is an ideal in vivo model for vascular biology research due to its genetic manipulability and optical transparency. To our knowledge, current reports on the role of cd248a in pericytes in zebrafish model are still quite limited.

In this study, we revealed that cd248a is highly expressed in developing embryos but is weakly expressed in most normal adult organs, except for the heart and kidney tissues. This is consistent with findings in humans and mice, where Cd248 expression persists only in the lung, kidney, and uterus postnatally39,40. However, the other paralog, cd248b, remains expressed in most adult organs. We further confirmed that cd248a is specifically expressed in pericytes at a higher rate and in a greater proportion than cd248b, resulting in expression patterns similar to those of pdgfrβ, a typical pericyte marker. Our findings align with previous scRNA-seq analysis, which also identified CD248a as being associated with pdgfrß+ pericytes41. In summary, these results indicated that cd248a could be a pericyte marker gene during the embryonic development of zebrafish.

To further explore the functions of the two cd248 paralogs in pericyte development, knockout zebrafish lines were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system and crossed with the Ki(pdgfrβ:Gal4) and Tg(UAS:GFP; fli1:DsRed) lines42. Compared with wild-type zebrafish, cd248a mutant zebrafish presented a deficit of pericytes during embryonic development, similar to the phenotype observed in tumor transplantation models, which have a lower density of pericytes in Cd248-deficient mice19. Double-mutant larvae did not exhibit a more severe pericyte deficiency, implying that only cd248a plays a vital role in pericyte development. The function of cd248b should be explored in future studies. We next characterized the BBB function of cd248a mutant larvae with a reduced pericyte population. Consistent with previous findings that pericytes are required for BBB formation and function43,44, cd248a mutant larvae presented a leaky BBB, but no brain hemorrhage was detected in our study. Taken together, these observations indicate that cd248a may function to accelerate pericyte proliferation to support intense angiogenesis in developing embryos or tumors.

To test whether cd248a promotes pericyte proliferation, we examined EdU incorporation in both wild-type and cd248a mutant larvae. The number of EdU+ pericytes was significantly lower in cd248a knockout larvae than in wild-type control larvae. Conversely, cd248a overexpression in wild-type zebrafish resulted in an increase in pdgfrβ+ pericytes. However, the increase was inhibited when the zebrafish larvae were treated with AG1295, a pharmacological Pdgfrβ inhibitor, suggesting that Pdgfrβ function is required for cd248a to regulate pericyte proliferation. Another finding that overexpressing pdgfrβ could restore the pericyte deficiency phenotype further supports this viewpoint. Previous work has shown that the Pdgfrb expression level is an intrinsic determinant of pericyte proliferation rate27,44, but we did not detect a change in pdgfrb expression in individual pericytes isolated from cd248a mutants and wild-type larvae. This is consistent with a Cd248 knockout mouse model in which the PDGFRβ expression levels in hepatic stellate cells are similar to those in wild-type controls, yet their proliferation could not be induced by PDGF-BB stimulation20. These results suggest that cd248a may regulate Pdgfrb functions through a non-transcriptional mechanism, likely involving the activation of downstream signaling pathways. It has been reported that the PI3K/Akt pathway, activated by PDGF/PDGFR signaling, is associated with cell proliferation, which mediates the regulation of p53, leading to cell cycle arrest29,30,31. Our findings of elevated expression of cell cycle arrest-related genes in cd248acc11/cc11 larvae confirmed this inference. Given the limitations of protein detection in the zebrafish pericyte model, further work is needed to explore this mechanism in greater depth in pericyte cell lines.

Another important function of cd248a in pericytes was documented in our work. We found that cd248a expression is increased under hypoxic conditions, consistent with previous reports that the transcription of CD248 is regulated by HIF-215. However, the reason for the upregulation of cd248a in the hypoxic microenvironment is still unclear. In our study, the increase in the number of apoptotic pericytes in cd248a mutant larvae after exposure to CoCl₂ was greater than that in the wild-type controls, and this increase could be rescued by injection of tp53 MO. Our results indicated that cd248a deficiency increases hypoxia-induced pericyte apoptosis in a tp53-dependent manner. Although the function of p53 in mediating apoptosis under hypoxia has been extensively investigated45,46, how cd248a regulates tp53 under hypoxia remains unclear.

Furthermore, we found that the expression levels of tp53, tp53 target gene (bax) and other proapoptotic genes (caspase3 and caspase9) in cd248a mutants were significantly increased after CoCl₂ exposure. In contrast, in the wild-type zebrafish, the expression levels of most genes did not change significantly. These results indicate that cd248a plays a crucial role in resisting hypoxia-induced apoptosis in pericytes, depending on the regulation of tp53.

In summary, this study investigated the functions of the cd248a and cd248b genes in zebrafish pericytes. In contrast to cd248b, cd248a appears to be more likely expressed in pericytes. Furthermore, cd248a promoted the expansion of pericytes, possibly by regulating Pdgfrb function. Additionally, cd248a is clearly involved in increasing pericyte resistance to hypoxia-induced apoptosis in a tp53-dependent manner, but the precise regulatory mechanisms of cd248a remain to be identified.

Methods

Ethical approval

The animal experiment was conducted according to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (Eighth Edition, 2011) and has been approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of the Third Military Medical University (Approval ID: AMUWE20223877).

Zebrafish culture

All fish were raised in an automatic water cycler system at 28.5 °C on a 14/10 h daily light cycle, and fed newly hatched brine shrimp twice each day. Embryos were maintained in E3 water. The transgenic lines Ki(pdgfrβ:Gal4) and Tg(UAS:GFP; fli1:DsRed) were used in this study to visualize pericytes and endothelial cells, respectively. These lines have been characterized by Bing et al.42.

Generation of the cd248a and cd248b mutant zebrafish

cd248a or cd248b in zebrafish was disrupted according to a standardized gene knockout protocol using CRISPR/Cas9 technique47. Briefly, target sites of cd248a and cd248b were designed using an online tool available at http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no. sgRNAs transcription templates were generated through PCR with T7-targetsite-F primers and a universal reverse primer gRNA-R (Supplementary Table 1). The sgRNAs and Cas9 capped mRNA were synthesized in vitro with a MAXIscript T7 Kit (Invitrogen, AM1314M) and Ambion mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Transcription Kit (Invitrogen, AM1344), respectively. Then, Cas9-capped mRNA (300 ng/μL) and sgRNA (30 ng/μl) were co-injected into zebrafish embryos at the single-cell stage. The T7E1 assay was performed to detect the efficiency using PCR product of genomic DNA from injected embryos at 48 hpf.

Whole-mount fluorescence in situ hybridization and antibody staining

Combined whole-mount fluorescence in situ hybridization and antibody staining in Tg(pdgfrβ:Gal4; UAS:GFP) zebrafish larvae was performed according to published protocols48. The fragment of cd248a was generated through PCR using the following primers: cd248a forward, 5′- CCCTCTTGACTTCCCTGGAG -3′; T7-cd248a reverse, 5′- TAATACGA CTCACTATAGGGCAAGCTGTCTTGTTTGCCAT -3′. cd248a antisense Fluo-labeled RNA probe was synthesized in vitro with T7 RNA-polymerase (Roche, cat. no. 10881767001). For the staining, a goat anti-GFP primary antibody (1:300, Invitrogen, PA5-143588) and Alexa-488 donkey anti-goat IgG secondary antibody (1:500, Invitrogen, A-11055) were used.

For TUNEL assays, embryos that had been labeled with a GFP antibody were incubated in 100 µl staining solution (Beyotime, C1089) at 37 °C for 1 h according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The embryos were then washed in PBST, mounted, and imaged. For EdU labeling, zebrafish embryos at 3 dpf were treated with 500 µM EdU containing 5% dimethylsulfoxide in embryo medium for 4 h at 28 °C on a shaker. They were then fixed in 4% PFA overnight. The GFP fluorescent was detected as described above, and the EdU labeled cells were detected using BeyoClickTM EDU Cell Proliferation Kit with Alexa Fluor 647 (Beyotime, C0081) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro mRNA synthesis and mRNA microinjection

The full open reading frame (ORF) of zebrafish cd248a (NM_001099228.3), cd248b (XM_021469088.2), and pdgfrβ (NM_001190933.1) were amplified using the PrimeSTAR Max Premix (Takara, R045Q). The pCS2-cd248a, pCS2-cd248b, and pCS2-pdgfrβ vectors were constructed by inserting their ORF into the EcoRI/SnaBI cloning sites of the pCS2+ vector. Capped mRNAs were then produced using Ambion mMESSAGE Mmachine T7 Transcription Kit (Invitrogen, AM1344). The purified mRNA was injected into the one-cell stage embryos at a concentration of 100 ng/μl. The samples were incubated at 28.5 °C before collection.

MO injection

The tp53 MO-ATG sequence, 5′-GCGCCATTGCTTTGCAAGAATTG -3′, was obtained from Gene Tools34 and solubilized in water at a concentration of 1 mM. The tp53 MO and a control MO were injected into the yolk of one-cell stage embryos at the same volume.

Drug treatment

To inhibit pigmentation, embryos were treated with 0.003% N-phenylthiourea (PTU; Sigma Aldrich, P7629) at 24 hpf. For PDGF receptor inhibitor assays, embryos were treated with 25 μM AG1295(MCE, HY-101957) or an equivalent volume of DMSO in E3 media from 2 dpf to 3 dpf. For hypoxic treatments, embryos were exposed to 0.5 or 1.0 mM CoCl2 (Sigma Aldrich, 31277) from 3 dpf to 4 dpf.

FACS analysis

To dissociate embryos and obtain single-cell suspensions, we followed established protocols with minor modification49. We used embryos with Ki(pdgfrβ:Gal4) and Tg(UAS:GFP;fli1:DsRed) transgenic backgrounds to sort EGFP-positive or DsRed-positive cells, thereby isolating pericytes and endothelial cells. WT or mutant embryos at 5 dpf with EGFP and DsRed fluorescence were disaggregated using the Papain Dissociation System (Worthington Biochemical, LK003150) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cell suspension was then used to sort out pericytes and ECs using the Beckman coulter Moflo XDP. Our gating strategy involved selecting the target cell population based on Forward Scatter and Side Scatter parameters, with positive cells being identified using negative control profiles as a reference.

Analysis of mRNA expression level

Total RNA was isolated from staged embryos, adult organs, or FACS-sorted zebrafish pericytes and endothelial cells using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Fastagen, 220010). The extracted RNA was reverse transcribed using RNA Reverse Transcription kit (TRANSGEN, AE341). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed using EasyTaq PCR SuperMix (TRANSGEN, AS111) in a 20 μL reaction contain 1 μL cDNA, with primers as indicated in Supplementary Table 1. Amplicons were visualized by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel using equal volume of PCR product. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using TransStart Green qPCR SuperMixon (TRANSGEN, AQ101) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad), following manufacturer’s instructions and using primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. The relative expression of selected genes was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method with 18 s as reference.

Western blot analysis

Sixty larvae from each group were collected in a single tube and lysed in a lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The following antibodies were used: p53 antibody (1:1000, GeneTex, GTX102965) and β-actin antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 8457). Vilber FUSION FX6 was used to image Western blots.

Measurement of brain vascular integrity

A dye diffusion assay was performed to analyze the integrity of BBB in vivo33,50. A volume of 10 nl of Alexa FluorTM-647 cadaverine (1 kDa, 0.5 mg/ml, Invitrogen, A30679) was injected into the blood circulation system of 5 dpf zebrafish larvae via the common cardinal vein. Images of the cerebrovasculature were captured immediately after the injection. The relative fluorescence intensity of the dyes was measured and analyzed by Qupath (v.0.2.3) software.

Imaging and quantification

For confocal imaging, embryos were anesthetized in 0.01% tricaine (Sigma, A5040) and mounted in 1.2% low-melting agarose (Invitrogen, 16520100), and covered with E3 water. Then embryos were imaged on a Zeiss LSM 900 confocal microscope using a 10x objective at a resolution of 1024 × 1024. Z-stacks were acquired in 5-μm increments. Quantification of pericytes in embryonic trunk or brain was performed using Qupath (v.0.2.3).

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical significance between different groups of samples was performed by ANOVA or two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses