CENPF (+) cancer cells promote malignant progression of early-stage TP53 mutant lung adenocarcinoma

Introduction

With the popularity of low-dose spiral CT in physical examination, the detection rate of early-stage lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) characterized by pulmonary nodules has increased year by year, and its precise prevention and treatment has become increasingly important [1]. Early-stage LUAD, mainly classified as stage IA, still has some heterogeneity, and its 5-year survival rate is only ~80% [2]. While some patients have a favorable prognosis requiring less invasive methods, an appreciable quantity of patients are still highly likely to relapse, which requires more progressive clinical management [2,3,4,5,6]. Therefore, the current single standardized clinical therapeutic strategy, radical lobectomy with lymph node dissection and without postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, has many drawbacks for individualized precision medicine of early-stage LUAD [7,8,9].

Risk stratification is the cornerstone of precise clinical intervention for early-stage LUAD. The existing risk stratification of early-stage LUAD mainly focuses on radiological and histopathological features. For example, the combination of the consolidation tumor ratio (CTR) and tumor size could effectively indicate the risk of lymph node metastasis and serve as the basis for sublobotomy (a limited surgery method for the low-risk type of early-stage LUAD) [4, 10], while pathological features such as micropapillary components, solid components, vascular invasion, and air diffusion often predict poorer prognosis and the possibility of benefit from postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for the high-risk type of early-stage LUAD [5, 11,12,13]. However, the existing risk classification remains flawed due to ambiguity (such as evidence for the classification of CTR values and size of solid components [14], combination and quantification of pathological features, etc. [15, 16]) and incomplete stratification, especially for high-risk types (the most high-risk IA3 subtype still outperformed stage IB in the eighth edition of TNM staging, which cannot suggest aggressive methods) [2].

Risk classification of early-stage LUAD could identify valuable molecular clues from carcinogenesis underlying preneoplasia to invasive adenocarcinoma. Based on bulk transcriptome and exon sequencing, it was found that with the evolution of early-stage LUAD, that is, from atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH), carcinoma in situ (AIS), microinvasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC), tumors exhibit more genetic mutations, aggressive behaviors, and immunosuppression [17,18,19,20]. Single-cell transcriptome sequencing (scRNA-seq) of pulmonary nodules with different radiological features revealed notable microenvironment discrepancies in the evolutionary pathological stages of early-stage LUAD [21, 22]. However, the specific molecular mechanisms underpinning the malignant progression of early-stage LUAD remain unclear in many aspects, severely hindering effective risk stratification for clinical management.

By multiomics technologies, such as scRNA-seq, bulk transcriptome and proteome analysis as well as in vivo and in vitro experiments, we demonstrated that cancer cells highly expressing centromere protein F (CENPF) promote the malignant progression of early-stage LUAD and could be applied as novel biomarkers for its risk stratification and precise clinical management.

Methods

Cell lines

Human LUAD cell lines (PC-9, HCC827, and H1975), a human lung cancer cell line (H1299), HEK293T cells, and mouse Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in RPMI‑1640 or DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. All cells were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested without mycoplasma contamination.

Infection and transfection

For stable infection, recombinant lentiviruses (Hanbio, Shanghai, China) for gene interference were introduced into cells (PC-9, HCC827) and organoid, followed by puromycin selection for stable models. For transient transfection, siRNAs (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) and plasmids (Hanbio; Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) were introduced into cells (PC-9, HCC827, H1975, H1299 and HEK293T) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The utilized nucleic sequences are listed in Table S1.

ScRNA-seq and RNA-seq (tissue bulk and cell lines)

Nine clinical specimens (AIS: n = 3; MIA: n = 3; IAC: n = 3) (female: n = 6; male: n = 3; ranging from 37 to 69 years old) used for scRNA-seq (under accession GSE189357, deposited at GEO: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) were collected from Tangdu Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University (Xi’an, China), in accordance with ethics authority approval and all participants provided informed consent. Detailed methods for scRNA-seq are similar to those used in previous studies [23]. In brief, after modified tumor sampling, a single-cell suspension was generated through enzymatic dissociation, filtration, centrifugation, and red split fusion, and then, droplet-based scRNA-seq was performed on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, CA, USA) platform after a final cDNA library was established (Genergy Inc., Shanghai, China). Cell Ranger (10x Genomics, CA, USA) was used to generate gene expression matrices based on the Ensembl GRCh38 human transcriptome. The quality control, integration and subsequent analysis of scRNA-seq data are described below (“Bioinformatics and statistical analysis”).

Sixty-five clinical specimens (NC: n = 5, AIS: n = 20, MIA: n = 17, IAC: n = 23) (female: n = 44; male: n = 21; ranging from 48 to 74 years old) used for bulk RNA-seq (under accession HRA005169; deposited at CNCB-NGDC: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/) were collected from Tangdu Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University (Xi’an, China), in accordance with ethics authority approval and all participants provided informed consent. Total RNA extracted from LUAD samples or cell lines (Knockdown model of CENPF in PC-9 cell lines by sh-NC/CENPF lentivirus; sh-NC: n = 3; sh-CENPF-1: n = 3; sh-CENPF-2: n = 3) (under accession HRA005374; deposited at CNCB-NGDC: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/) was prepared to establish a cDNA library, which was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq™ 6000 platform (LC Bio Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). The inclusion criteria were carefully defined as the following: (1) histological diagnosis of LUAD; (2) maximum diameter of the tumor ≤ 3.0 cm; (3) no lymphatic metastasis or distant metastasis; (4) no prior history of any other malignant tumors; and (5) radical lobectomy/segmentectomy.

Tissue microarray (TMA), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and evaluation

A total of 262 LUAD specimens (131 paired cancerous tissues and normal tissues) (female: n = 46; male: n = 85; ranging from 33 to 82 years old) for TMA construction as well as early-stage LUAD specimens (AIS: n = 9; MIA: n = 12; IAC: n = 16) (female: n = 20; male: n = 17; ranging from 38 to 78 years old) were collected from Tangdu Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University (Xi’an, China), in accordance with ethics authority approval and all participants provided informed consent; detailed information about TMA can be found our previous study [24]. In brief, microarrays, specimens and organoids were dewaxed, antigen repaired, treated with hydrogen peroxide and blocked; then, they were incubated with specific primary antibodies (Ki-67: GB111499, Servicebio, Wuhan, China; CENPF: GTX70137, GeneTex, CA, USA; TERT: 54247, SAB, MD, USA; TERT: ab230527, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, and GB11915, Servicebio; Napsin A: GB121012, Servicebio) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibody, followed by staining, counterstaining and microscopy. The slides were scanned, digitalized, and quantified using a Pannoramic MIDI based on the H-score (3D HISTECH, Budapest, Hungary) [25].

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT‒PCR)

Total cell RNA was extracted using RNAiso reagent (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and cDNA was synthesized from 1.0 μg of total RNA using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TaKaRa). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa) with an Mx3005p Real-Time PCR detection system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). β-actin was used as an internal reference. The 2−ΔΔCt method was used to determine relative gene expression. The sequences of primers used are listed in Table S1.

Western blot (WB)

Proteins from cell lysates were separated by SDS‒PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, which was incubated with primary specific antibodies (β-actin: 4970S, CST, MA, USA; cyclin A2: 27242-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China; cyclin B1: 28603-1-AP, Proteintech; cyclin D1: 26939-1-AP, Proteintech; cyclin E1: 11554-1-AP, Proteintech; TERT: ab230527, Abcam; TP53(DO-1): sc-126, Santa Cruz, USA and 60283-2-Ig, Proteintech; CENPF: ab5, Abcam and 58982S, CST; Histone H3: 4499S, CST; HA: T501, SAB and 3724S, CST; CEBPB: 40657, SAB; MAZ: 44263, SAB; Flag: 48043, SAB and 66008-4-Ig, Proteintech; E2F1: 3742S, CST), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (specifically, we used conformation-specific anti-rabbit IgG (5127, CST) and anti-mouse IgG (ab131368, Abcam) for immunoprecipitation). ECL reagent (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) was applied for protein detection.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells were incubated with the appropriate primary antibody (Ki-67: 27309-1-AP, Proteintech; CENPF: GTX70137, GeneTex; PCNA antibody: ab29, Abcam) at 4 °C overnight in a moist chamber, washed with PBS, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488/594- or CY3-conjugated secondary antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI.

Plate and soft agar colony formation experiments

Cells (CENPF-knock-down model of PC-9 and HCC827 cell lines) in the logarithmic growth stage were fully mixed into a single-cell suspension, seeded in six-well plates with 2 ml of medium containing 10% FBS with or without 0.35% agar, stained with crystal violet after 2–3 weeks, and the area of colonies was measured by Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, MD, USA). At least three independent experiments were performed in triplicate.

Tumoursphere formation

Cells (CENPF-knock-down model of PC-9 and HCC827 cell lines) were cultured in serum-free medium with cell line-specific annexing agents. A total of 1000–5000 cells were seeded in six-well ultralow attachment plates (Corning, NY, USA) and cultured for 1–2 weeks. The area of spheres was scored by Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, MD, USA). At least three independent experiments were performed in triplicate.

CCK-8 proliferation assays

Cells (CENPF-knock-down model of PC-9 and HCC827 cell lines, with or without telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) overexpression) in the logarithmic growth phase were fully mixed, inoculated in a 96-well plate, and continuously cultured for 96 h, and the number of living cells was measured every 24 h with a CCK-8 kit (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). At least three independent experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cell cycle assays

Cells (CENPF-knock-down model of PC-9 and HCC827 cell line) were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with cold 75% ethanol, incubated with RNase A, stained with propidium iodide, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. At least three independent experiments were performed in triplicate.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-(LC-MS) based proteomic analysis

The primary antibody (CENPF: ab5, Abcam; HA: 3724S, CST; Flag: 66008-4-Ig, Proteintech; E2F1: 3742S, CST and TP53: 60283-2-Ig, Proteintech) was added in an optimal amount to magnetic beads diluted in PBS with Tween-20 and then incubated with rotation at room temperature for crosslinking. After that, the supernatant was removed, and the bead-antibody complex was washed by using a magnet. Then, the cell samples extracted using a MinuteTM total protein extraction kit (Invent Biotechnologies, Plymouth, MN, USA) were added to the bead-antibody complex to immunoprecipitate the target antigen. Based on the experimental objectives, for a portion of the samples, SDS loading buffer was then added prior to SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis.

Finally, the supernatant was removed, and the beads, antibody, and antigen were gently washed and collected for further identification by LC‒MS (in-gel) following the manufacturer’s instructions (LC Bio Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) (PC-9 cell lines, IP of CENPF: n = 3; IgG: n = 3; Input: n = 1; under accession OMIX004768; deposited at CNCB-NGDC: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/) and western blotting. In the LC–MS process, after the protein is accurately quantified, its three-dimensional structure is first unfolded through reductive alkylation. Following enzymatic digestion, the resulting peptide segments are extracted. These peptide segments are then analyzed using mass spectrometry technology (Q-Exactive, Thermo Scientific) to obtain their respective mass spectra. Finally, the protein present in the sample is identified using protein identification software (Proteome Discoverer). The quality of the identification is rigorously assessed based on factors such as the distribution of peptide matching errors, the charge distribution of the peptides, and the length distribution of the identified peptide sequences.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays were conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol (The SimpleChIP® Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit: 9005, CST). Briefly, cells were fixed with formaldehyde, and the chromatin was fragmented by enzymatic digestion and sonication. Then, precleared chromatin was immunoprecipitated overnight with specific antibodies (anti-dimethyl-histone H3 (Lys4): 07–030, Merck Millipore; anti-trimethyl-histone H3 (Lys4): 07–473, Merck Millipore; anti-trimethyl-histone H3 (Lys27): 07–449, Merck Millipore; anti-acetyl-histone H3 (Lys9): 07–352, Merck Millipore). The following antibodies were selected for negative and positive controls: Normal Rabbit IgG: #2729, CST; Histone H3 (D2B12) XP® Rabbit mAb: #4620, CST. The enrichment of specific DNA fragments were analyzed by qPCR. The primers used are listed and explained in Table S1.

Luciferase reporter assays

Luciferase activity was determined in cell lysates using a dual-luciferase assay system (Promega, WI, USA). The CENPF promoter fragment (2000 upstream from the transcription start point of the human CENPF gene) was cloned and inserted into the pGL3 vector (Promega) to establish the pGL3-CENPF-Promoter-Luc plasmid. Moreover, the pRL-TK plasmid (Promega) carrying Renilla luciferase was co-transfected for normalization.

Patient-derived organoid (PDO) culture

Briefly, isolated fresh LUAD tissues (stage IA) obtained from Tangdu Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University in accordance with ethics authority approval, were cut into pieces, washed, and dissociated in digestion buffer (Advanced DMEM/F12 medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) with 10% penicillin/streptomycin, 1.5 mg/mL collagenase type II, 500 U/mL collagenase type IV, 0.1 mg/mL dispase type II, 10 μM Y-27632 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, England) and 1% FBS) for 0.5 –1 h at 37 °C. After washing, filtering with a 70-μM cell strainer (Biosharp), and centrifugation, the cell pellets were embedded in Matrigel (Corning), plated in 24-well plates and cultured in medium containing Advanced DMEM/F12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), Noggin (R&D Systems), R-Spondin (R&D Systems), EGF (R&D Systems), Glutamax (Invitrogen), HEPES (Invitrogen), N-2 additive (Invitrogen), B27 cell culture additive (Thermo Fisher Scientific), N-acetylcysteine (Tocris Bioscience), nicotinamide (Tocris Bioscience), A83-01 (Tocris Bioscience) and SB202190 (Sigma-Aldrich). The medium was changed approximately every 4 days.

Cell-derived transplantation tumor models

LLC cells in the logarithmic growth phase (5 × 105 cells/100 µl) were subcutaneously injected into the right posterior flank of each nude mouse (GemPharmatech, Nanjing, China, 4-week-old). Once the tumor volume reached ~50 mm3, mice were randomized into the indicated groups (5 animals/group). Intratumour injection of scramble or adeno-associated virus 6 (AAV6)-sh-CENPF was performed once every 2 days, four times. The tumors were measured every 3 days. Mice were killed 4 weeks later, and tumors were further assessed by weight and IHC.

Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models

Tumors from one LUAD patient (invasive lung adenocarcinoma, IIA: T2bN0M0) were fragmented and then subcutaneously transplanted into immunodeficient mice for engraftment to build PDX models (Tangdu Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China and GemPharmatech, Nanjing, China). After growth, the tumors were subcutaneously transplanted into 10 NOD/ShiLtJGpt-Prkdcem26Cd52Il2rgem26Cd22/Gpt (NCG) mice (GemPharmatech, Nanjing, China, 7-week-old). Once the tumor volume reached ~50 mm3, mice were randomized into the indicated groups (5 animals/group). Intratumour injection of scramble or sh-CENPF lentivirus was performed once every 3 days, four times. The tumors were measured every 3 days. Mice were killed 4 weeks later, and tumors were further assessed by weight and IHC.

Autochthonous mouse models of LUAD

Seven-week-old echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (EML4-ALK)-LSL mice (Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Shanghai, China), were intratracheally intubated with purified AAV6-Cre to trigger spontaneous LUAD derived from oncogenic EML4-ALK protein, as well as scramble or AAV6-sh-CENPF (6 animals/group). Mice were killed 3 weeks following virus infection, and the whole lungs were examined by haematoxylin–eosin staining (HE) and IHC.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

CENPF autoantibody production in patient serum was detected using an ELISA kit (Human ACA;CENPF ELISA Kit, Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China). Clinical serum (NC: n = 21; AIS: n = 236, IA: n = 286) (female: n = 176; male: n = 313; missed: 54; ranging from 25 to 84 years old) were collected from Tangdu Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University (Xi’an, China), in accordance with ethics authority approval and all participants provided informed consent. Briefly, micropores were precoated with antibodies specific to the target antigens. Subsequently, 50 µL of the specimen, standard substance, and HRP-labeled detection antibody were added. The samples were incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature, followed by thorough washing and the addition of chromogenic substrate reagents. The absorbance (OD value) was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite 200 Pro, Tecan, Switzerland), and the sample concentrations were calculated accordingly.

Public datasets

The bulk transcriptome data and clinical information of LUAD were acquired from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (TCGA-LUAD) [26] and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (GSE10072 [27], GSE13213 [28], GSE32863 [29], GSE41271 [30], GSE42127 [31], GSE43458 [32], GSE63459 [33], GSE72094 [34]). The scRNA-seq data of LUAD in E-MTAB-6149 were downloaded from ArrayExpress [35]. The CancerSEA and Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) databases also provided information on the transcriptome profiles of single cells and cell lines in LUAD [36, 37].

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

For scRNA-seq data, the R package Seurat was used for analysis [38]. Briefly, after quality control (gene numbers between 200 and 5000), the gene expression matrix was normalized (Function: NormalizeData), and 2000 genes with the most highly variable expression were selected (Function: FindVariableFeatures). The integrated data (Function: FindIntegrationAnchors and IntegrateData) were scaled, the dimensionality was reduced (Function: RunPCA, RunUMAP, and RunTSNE), and the data were clustered (Function: FindClusters; Total cells: resolution = 0.1; Epithelial cells: resolution = 0.2). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (Function: FindAllMarkers) with differences indicated by a P value < 0.05 and a log2 fold change (log2FC) > 0.25 were considered marker genes, which were used to identify cell types. Copy number variation (CNV) was determined to identify malignant epithelial cells (R package: infercnv). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed to assess biological significance based on the Hallmark databases (based on DEGs, ranked in FC order) [39].

For bulk transcriptome data, RNA-seq of cell lines and proteomic analysis, z-scaling was used for normalization, and UMAP/T-SNE (Packages: umap and Rtsne) was used to visualize the distribution of samples from different sources [40, 41]. The single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) was used to quantify the relative content proportion of specific cells (DEGs of these cancer cells as background gene set) in the bulk transcriptome data [42]. Biological process enrichment was based on Reactome databases (R package: ReactomePA), and GSEA was performed to assess biological significance based on the Hallmark and Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases (based on associated genes of target genes, ranked in correlation coefficient order) (clusterProfiler package) [39, 43,44,45]. The DESeq2 package and limma package were utilized for DEGs analysis [46, 47].

Cox analysis, Kaplan‒Meier curves, and the log-rank test and weighted log-rank test (Peto-Peto test) were used for survival analysis (Packages: survival and survminer). The Benjamini‒Hochberg (BH) method was used for P value correction for multigroup comparisons. A nomogram was used to estimate survival probability (Packages: rms). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used for the diagnostic analyses (Packages: pROC). The GitHub platform and devtools packages were used for R package development and storage. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Kruskal–Wallis test, two-group t test, ANOVA, Dunnett’s t test, Tukey’s test, and Dunn’s test were utilized for differential analysis of measurement data according to data characteristics. Pearson correlation analysis was used to estimate correlativity. The chi-square test was used for rate comparison. The sample size was calculated utilizing the PASS software, taking into account the pre-experimentally estimated effect size, standard deviation, and the proportion of individuals within each group. The utilization of the random table method ensures the allocation of participants into groups in a randomized manner (investigator was blinded to the group allocation), enhancing the rigor and validity of the experimental design. The R package ggplot2 was used for graphing. R language was adopted for the above-mentioned operations, with a two-sided P value (or adj. P value) <0.05 considered to be statistically significant [48].

Results

High CENPF expression in cancer cells might be an important event in early-stage LUAD progression

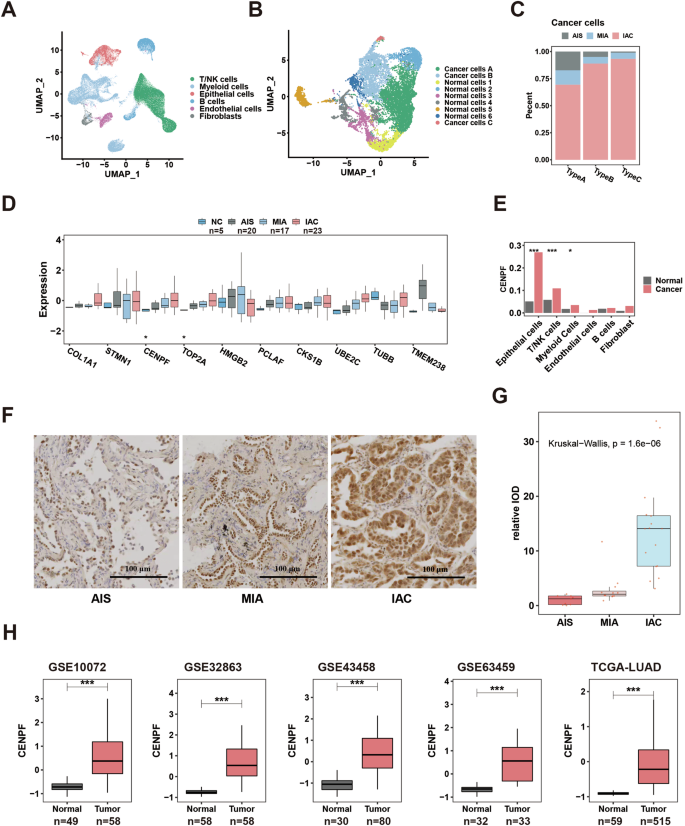

We performed scRNA-seq of clinical samples from three progressive pathological stages (AIS: n = 3, MIA: n = 3, IAC: n = 3) of early-stage LUAD. T/NK cells, myeloid cells, epithelial cells, B cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts were identified by cell clustering and specific marker genes (Figs. 1A and S1a). Cancer cells still play crucial roles in the carcinogenic process. We further performed subclustering of epithelial cells and distinguished normal cells from cancer cells according to copy number variation (Figs. 1B and S1b). We found that a special cluster of cancer cells (cancer cell type C) accumulated gradually with AIS-MIA-IAC progression (Fig. 1C), with more aggravated malignant characteristics in bioenrichment analysis in the hallmark database by GSEA of DEGs, ranked in FC order (Fig. S1c), indicating the possible critical role of this cluster in the malignant progression of early-stage LUAD. We further analyzed the key genes mediating this cancer subcluster. We compared the transcriptomic profile of the top 10 marker genes of cancer cell type C (in FC order) in four different pathological stages of early-stage LUAD tissue specimens (normal tissue, NC: n = 5; AIS: n = 20, MIA: n = 17, IAC: n = 23), and we found that two genes (CENPF and DNA topoisomerase II alpha, TOP2A) showed significant gradual increases (Fig. 1D). Compared with TOP2A, a classic enzyme that controls and alters the topological states of DNA during transcription [49, 50], CENPF has intriguing characteristics with a more complex structure and diverse functions and has shown carcinogenic potential in a variety of tumors [51,52,53]. Therefore, CENPF was selected for further study. Furthermore, we confirmed in pathological specimens (AIS: n = 9, MIA: n = 12, IAC: n = 16) that CENPF showed a gradual increase in protein level along with the evolution stage of early-stage LUAD (AIS-MIA-IAC), suggesting the possible role of CENPF in the malignant evolution of early-stage LUAD (Fig. 1F, G). It is evident that CENPF exhibits a diverse distribution, initially localized in the nucleus but gradually extending to the cytoplasm. This pattern suggests a broader range of functions beyond its classical role in the centromere spindle within the nucleus, aligning with similar notions proposed in prior literature [53, 54]. In addition, we confirmed the high transcription of CENPF in LUAD tissue in five large independent datasets (Fig. 1H). Moreover, we demonstrated that highly transcriptionally expressed CENPF in LUAD was mainly concentrated in cancer cells (epithelial cells) rather than other cells in a public single-cell LUAD dataset (E-MTAB-6149) by comparing its expression among different cell types between normal and cancerous tissue of LUAD (Fig. 1E) (Fig. S1d: marker genes; Fig. S1e: clustering of different cells). We subsequently demonstrated that LUAD has a high CENPF protein level in a tissue microarray (Fig. S1f), with a significant difference (Fig. S1g). These findings suggest that high CENPF expression in cancer cells may be a key event in the malignant evolution of early-stage LUAD.

A Cell distribution in the microenvironment of early-stage LUAD via scRNA-seq of clinical samples from three progressive pathological stages (AIS: n = 3; MIA: n = 3; IAC: n = 3). B The distribution of malignant and benign epithelial cells in early-stage LUAD via scRNA-seq of clinical samples from three progressive pathological stages (AIS: n = 3; MIA: n = 3; IAC: n = 3). C The content distribution of different malignant epithelial cells in three progressive pathological stages (AIS, MIA, IAC). D Expression distribution of the top 10 highly expressed genes in Type C malignant epithelial cells in four progressive pathological stages (NC: n = 5; AIS: n = 20; MIA: n = 17; IAC: n = 23). E The expression of CENPF in microenvironment cells via scRNA-seq of LUAD and normal tissue. F CENPF protein expression in pathological specimens of the progressive stage of early-stage LUAD (AIS: n = 9, MIA: n = 12, IAC: n = 16). G Statistical comparison of CENPF protein expression in early-stage LUAD (AIS: n = 9, MIA: n = 12, IAC: n = 16). H The expression of CENPF in LUAD and normal tissue of five bulk transcriptional datasets. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. The boxplots indicate median (center), 25th and 75th percentiles (bounds of box), and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles (whiskers). Wilcoxon rank-sum test (E, H). Kruskal–Wallis test (D, G). CENPF centromere protein F, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, AAH atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, AIS carcinoma in situ, MIA microinvasive adenocarcinoma, IAC invasive adenocarcinoma, scRNA-seq single-cell transcriptome sequencing, NC Normal tissue.

CENPF promotes malignant progression of early-stage LUAD by facilitating the proliferation and stemness maintenance of cancer cells

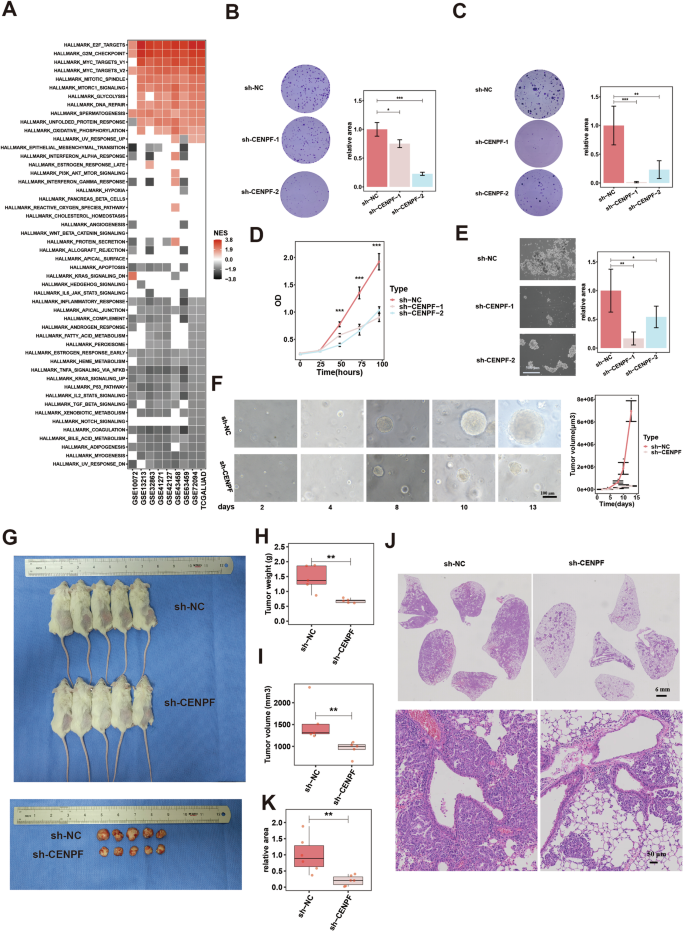

Next, we explored the biological function of CENPF in early-stage LUAD. By GSEA of CENPF-associated genes (ranked in correlation coefficient order), we found that CENPF was positively correlated with malignant proliferative potential in LUAD tissues (9 datasets) (Fig. 2A) and individual LUAD cells (Fig. S2a: single-cell database, CancerSEA, http://biocc.hrbmu.edu.cn/CancerSEA/; Fig. S2b: LUAD cell lines, CCLE https://depmap.org/portal/). We also demonstrated a significant positive correlation between the gene expression of CENPF and the proliferative index Ki-67 (MKI67) in LUAD tissue (8 datasets) (Fig. S2c), as well as protein expression (LUAD tissue microarray) (Fig. S2d, e). Similarly, we also demonstrated significant positive association between CENPF and malignant proliferative potential both by GSEA of CENPF-associated genes (ranked in correlation coefficient order) (Fig. S2f: Hallmark; Fig. S2g: KEGG and the correlation with MKI67 expression (Fig. S2h) in stage IA LUAD (two large datasets, GSE72094, n = 150; TCGA-LUAD, n = 131). Besides, in different pathological stages evolving to stage IA (AIS-MIA-IAC), there was still a strong positive correlation between the expression of CENPF and MKI67 (Fig. S2I).

A Bioenrichment of CENPF expression in nine LUAD datasets by GSEA based on associated genes of CENPF (ranked in correlation coefficient order). B Plate colony formation images (left) and quantification data (right) for CENPF knockdown cell models of PC-9 (sh-NC/CENPF lentivirus). C Soft agar colony formation images (left) and quantification data (right) for CENPF knockdown cell models of PC-9. D Proliferative ability assessed by CCK-8 experiments for CENPF knockdown cell models of PC-9. E Tumorsphere formation images (left) and quantification data (right) for CENPF knockdown cell models of PC-9. F Images (left) and quantification data (right) of growth of PDOs for CENPF knockdown models (sh-NC/CENPF lentivirus). Tumors formation in LUAD-derived PDX models treated with sh-NC/CENPF lentivirus, images (G) and quantification data (H, tumor weight; I, tumor volume), n = 5 mice per group. Tumors formation in autochthonous mouse models of LUAD driven by EML4-ALK treated with AAV6-sh-NC/CENPF, images (J) and quantification data of tumors size (K), n = 6 mice per group. *P< 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. N ≥ 3, Data are presented as mean ± SD. The boxplots indicate median (center), 25th and 75th percentiles (bounds of box), and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles (whiskers). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s t test for multiple comparisons test (B, C, E). Multi-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (D, F). Wilcoxon rank-sum test (H, I, K). CENPF centromere protein F, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, GSEA gene set enrichment analysis, NC negative control, PDO patient-derived organoid, PDX patient-derived xenograft, EML4-ALK echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 and anaplastic lymphoma kinase, AAV6 Adeno-associated virus serotype 6.

Then, we investigated the biological function of CENPF in vitro and in vivo. In two cell lines by recombinant lentivirus infection (Fig. 2, Fig. S3: PC-9; Fig. S4: HCC827), CENPF knockdown (Figs. S3a–c and S4a–c) significantly reduced cell cloning ability (Figs. 2B and S4d: plate colony; Figs. 2C and S4e: soft agar colony), cell proliferation (Fig. 2D and S4f: CCK-8 experiments; Figs. S3d and S4g: detection of the cell proliferation indices Ki-67 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCN(A)), cell cycle progression (Figs. S3g and S4j: cell cycle analysis; Figs. S3f and S4k: detection of the cell cycle checkpoints), stemness maintenance (Figs. 2E and S4h: tumoursphere formation; Figs. S3e and S4i: detection of markers for stem cells). PDO are pivotal models for cancer research, as they mimic the histological and stereochemical structural features of the original tumor [55]. We established an organoid model of early-stage LUAD (stage IA), which maintained histological features and morphology consistent with the original lesion (Fig. S3I). By lentivirus RNA interference technology, we established CENPF-KD model of organoids (Fig. S3h). We found that in the CENPF-KD group, the organoid increased significantly slower than that in the control group (Fig. 2F).

Finally, we explored the role of the CENPF in in vivo models of LUAD. A mouse lung cancer model was established in nude mice by inoculating mouse LLC cells subcutaneously. AAV6-mediated shRNA of CENPF (AAV6-sh-CENPF) was injected into tumors when the tumor size reached 50 mm3 (once every two days, four times). After 14 days, we found that the tumor volume and weight in the AAV6-sh-CENPF group were significantly lower than those in the control group (Fig. S3j–l). PDX model can accurately reconstruct the characteristics of the tumor microenvironment and is considered an admirable preclinical model for cancer [56]. In the PDX model of LUAD tissue, lentivirus-mediated shRNA of CENPF (sh-CENPF) was injected into tumors when the tumor size reached 50 mm3 (once every three days, four times). After 15 days, the tumor volumes and weights of the sh-CENPF group were significantly lower than those of the control group (Fig. 2G–I). Finally, we established autochthonous mouse models of LUAD driven by EML4-ALK mutation triggered by intratracheal intubation with AAV6-Cre (EML4-ALK is the classic driving gene of LUAD [57]. The spontaneous tumor formation model based on EML4-ALK was faster than other driving gene models (EGFR, KRAS, TP53, etc.) and chemical-induced models [58, 59], also with a good tumor formation effect). One week after AAV6-Cre administration, AAV6-sh-CENPF and its control were intratracheally intubated into mice. After 3 weeks, we found that the number and size of spontaneous LUAD in the experimental group were significantly lower than those in the control group (Fig. 2J, K).

In conclusion, these findings suggest that CENPF plays a carcinogenic role in early-stage LUAD possibly by enhancing the malignant proliferation and stemness maintenance of cancer cells.

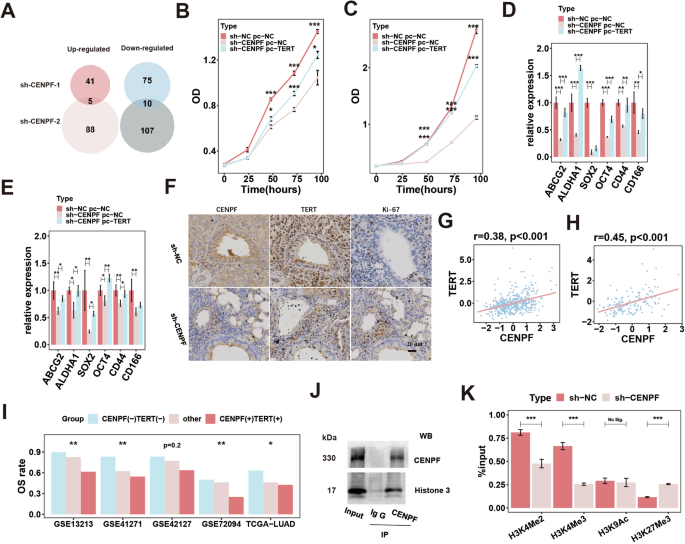

CENPF activates TERT transcription by regulating methylation of histone H3 to facilitate oncogenic effects

To investigate the underlying oncogenic mechanism of CENPF upon tumor cells, we performed RNA-seq of two CENPF knockdown (KD) models and negative control (NC) PC-9 cells (sh-NC: n = 3; sh-CENPF-1: n = 3; sh-CENPF-2: n = 3). Via differential gene analysis (log2 FC >1 and adj.P value < 0.05) (Fig. S5a) and intersection analysis (Fig. 3A), we identified ten downregulated genes and five upregulated genes in the control group compared with the CENPF-KD group. Among these candidates, upregulated TERT is a critical oncogene for maintaining telomere activity and facilitates rapid cancer cell proliferation and stemness [60,61,62]. Therefore, we focus on analyzing the relationship between CENPF and TERT. We further confirmed by qPCR (Fig. S5b) and western blotting (Fig. S5d) that CENPF knockdown significantly inhibited TERT expression in PC-9 cells and HCC827 (Fig. S5c, e) cells. Then, we overexpressed TERT in the CENPF-KD model (Fig. S5f) and found that overexpression of TERT could partially reverse the inhibitory effect of CENPF knockdown on proliferation (Fig. 3B) and stemness maintenance (Fig. 3D) in PC-9 cells and HCC827 cells (Figs. S5g and 3C, E).

A intersection analysis of DEGs in two CENPF-KD models of PC-9 cells (sh-NC/CENPF lentivirus); Proliferative ability examined by CCK-8 assay in CENPF-KD model with TERT overexpression of PC-9 (B) and HCC827 (C) cell lines (sh-NC/CENPF lentivirus; pc-NC/TERT plasmids); Detection of markers for stem cells in CENPF-KD model with TERT overexpression of PC-9 (D) and HCC827 (E) cell lines (sh-NC/CENPF lentivirus; pc-NC/TERT plasmids). F Protein content of CENPF, TERT and Ki-67 by IHC detected in tumors of in autochthonous mouse models of LUAD driven by EML4-ALK treated with AAV6-sh-NC/CENPF. Correlation between CENPF and TERT in LUAD (G) and stage IA LUAD (H). I Combined OS rate analysis of CENPF and TERT in five LUAD datasets. J IP of CENPF and histone H3. K Epigenetic modifications of H3 histone examined by ChIP assay in CENPF-KD model of PC-9 cell lines. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. N ≥ 3. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Multi-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (B, C). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s t test for multiple comparisons test (D, E). Pearson correlation analysis (G, H). The chi-square test (I). Two-group t test (K). CENPF centromere protein F, TERT telomerase reverse transcriptase, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, DEGs differentially expressed genes, KD knockdown, IHC immunohistochemistry, NC negative control, EML4-ALK echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 and anaplastic lymphoma kinase, AAV6 Adeno-associated virus serotype 6, OS overall survival, IP immunoprecipitation, WB western blot, ChIP chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Furthermore, in vivo models of LUAD, IHC of tumor specimens showed that CENPF expression was significantly decreased in CENPF-KD, group, while TERT and Ki-67 exhibited consistent decreased expression, compared to that of the control group (Fig. S5m: mouse lung cancer modes built by inoculating LLC cells subcutaneously; Fig. S5n: PDX model of LUAD tissue; Fig. 3F: autochthonous mouse models of LUAD driven by EML4-ALK mutation). Moreover, we further explored the presence and function of the CENPF-TERT axis in LUAD tissues from patients and found that there was a positive correlation between CENPF and TERT expression levels (Fig. 3G), especially in stage IA LUAD (Fig. 3H). Furthermore, we classified LUAD patients into three groups based on the expression levels of CENPF and TERT (CENPF(-) TERT(-), other and CENPF(+) TERT(+)) and found that the overall survival (OS) rate of patients in the three groups showed a gradual decline, indicating that the CENPF-TERT oncogenic axis has significant clinical value (Fig. 3I).

Finally, we explore the potential specific regulatory mechanism of CENPF on TERT. We conducted an immunoprecipitation (IP) experiment to investigate CENPF-interacting proteins in PC-9 cells (Fig. S5h). We obtained protein samples from the IgG group (n = 3) and IP group (n = 3) for mass spectrometry analysis and identified intersecting proteins in each group as enriched proteins in this group, among which 219 were enriched proteins in the IP group (Fig. S5i) and 121 were enriched proteins in the IgG group (Fig. S5j). The IgG group-enriched proteins were deducted from the IP group-enriched proteins, and 116 CENPF-interacting proteins were obtained (Fig. S5k). Bioenrichment analysis in the Reactome database showed that CENPF-binding proteins were significantly enriched in histone methylation and acetylation pathways (Fig. S5l). The methylation and acetylation of histone H3 are important regulatory modes of TERT content [63]. Also, in the above proteomics analysis, histone H3 was significantly enriched in CENPF-binding protein precipitates (Table S2). Therefore, we speculated that CENPF may interfere with the methylation and/or acetylation of histone H3 to regulate TERT. Then, we demonstrated that CENPF could bind to histone H3 by IP experiments (Fig. 3J). Subsequently, we performed ChIP experiment in the CENPF-KD and control cells using antibodies against canonical histone modification sites in TERT (such as H3K27Me3, H3K4Me2, H3K4Me3, and H3K9Ac) and corresponding specific primers for detecting the TERT promoter region by qPCR. In fact, methylation of Lys4 histone H3 (MeK4H3) is associated with active gene transcription [64, 65], where methylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 are generally associated with inactive genes [66]. Acetylation of promoter histones H3 are generally considered to allow the gene to be permissive for transcription [67]. We found that CENPF probably regulated methylation of histone H3 (repression of H3K27Me3 and activation of H3K4Me2 and H3K4Me3), thus might actively regulating TERT expression by epigenetic modification (Fig. 3K). These findings indicate that CENPF promotes the progression of cancer cells by augmenting TERT transcription, potentially through the regulation of histone H3 methylation.

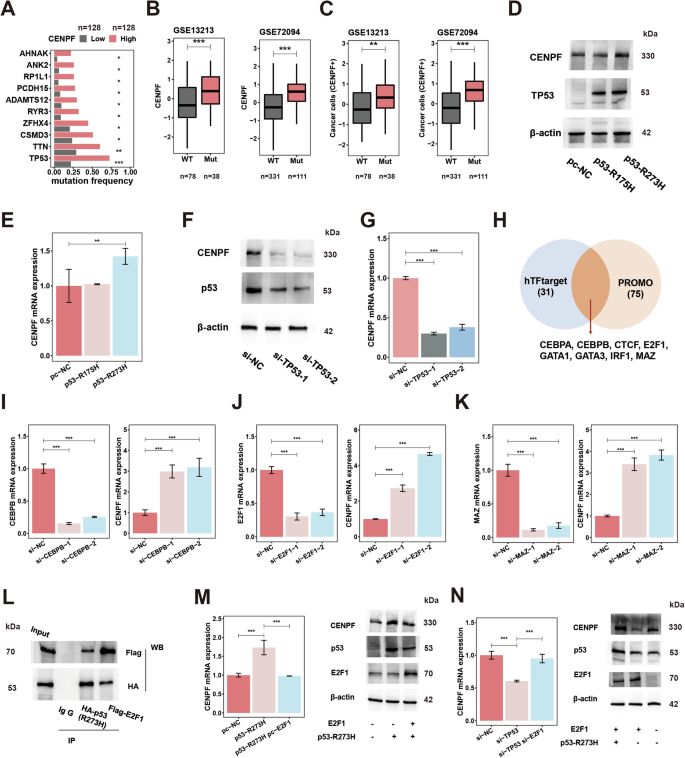

The mutant TP53 protein binds to E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1) and represses its transcriptional inhibition of CENPF

The specific reason for the abnormal expression of CENPF or accumulation of cancer cells (CENPF+) in early-stage LUAD is critical to fully understand carcinogenic function of these cancer cells. First, the TCGA-LUAD cohort containing mutation records was divided into two groups based on CENPF expression (Fig. S6a). We found that TP53 mutations were the most significant genomic changes in the high CENPF expression group compared to the low CENPF expression group (Fig. 4A). The higher CENPF expression, as well as a higher level of cancer cells (CENPF+) examined by ssGSEA in the TP53 mutant group, was further demonstrated in two LUAD transcription datasets (Fig. 4B, C). TP53 is known as the guardian of the genome, and its mutation is an important genetic event in the occurrence and development of tumors [68]. TP53 mutations are widespread in tumors; ~40% of LUAD cases have TP53 mutations, and TP53 mutations are also reported to be the driving mutation events in the malignant progression of early-stage LUAD (AIS-MIA-IAC) [17, 19, 69]. TP53 mutations in tumors are mainly missense point mutations caused by single nucleotide substitutions [70]. In the TP53-null lung cancer cell line H1299, the hotspot (high frequency) TP53 mutant plasmid (p53-R175H, p53-R273H) was overexpressed, and CENPF content was increased in the mutant group (p53-R273H) (Fig. 4D, E). In addition, we silenced the overexpression of the mutated TP53 protein in H1299 cells (p53-R273H) by small RNA silencing, and we found that CENPF content was reduced (Fig. S6b). We further specifically silenced the mutated TP53 protein in the TP53-mutated LUAD cell line H1975 (p53-R273H) by small RNA silencing, and we found that CENPF content was significantly reduced (Fig. 4F, G). TP53-mutated proteins can regulate the transcription of tumor-related molecules by themselves and/or by recruiting and binding transcription factors or by affecting copy number variation [71]. In the TCGA-LUAD database, it was found that the TP53 mutant group had no significant change in CENPF copy number variation compared with the wild-type group (Fig. S6c), and the correlation between the copy number of CENPF and its expression was weak (Fig. S6d). These results suggest that copy number variation may not be the main reason for the high expression of CENPF in early-stage LUAD. Therefore, we focused on the transcriptional regulation of TP53 upon CENPF. We used the hTFtarget (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/hTFtarget) and PROMO (https://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3) databases to predict CENPF transcription factors (ChIP evidence) and identified eight transcription factors with the highest scores (Fig. 4H). By two small RNA silencing experiments in PC-9 cells, we found that three transcription factors, MYC-associated zinc finger protein (MAZ), CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta (CEBPB), and E2F1, could uniformly inhibit CENPF expression (Figs. 4I–K and S6e–i). Furthermore, in HCC827 cells, we found that among the three transcription factors, only E2F1 consistently inhibited CENPF expression (Fig. S6j–l). We constructed MAZ-, CEBPB-, and E2F1-overexpressing transcription factor (Flag-tagged) plasmids and promoter plasmids of the potential binding region of CENPF (Fig. S6n). In HEK293T cells, a dual fluorescein reporter gene assay confirmed that E2F1 could transcriptionally inhibit CENPF, suggesting that E2F1 was a new transcriptional suppressor of CENPF (Fig. S6m). The classic tumor regulator E2F1 exhibits significant functional diversity and contrasting roles in cancer, varying according to its molecular status, cellular context, and tumor stage [72, 73]. This current study further underscores the intricate functions of E2F1 in tumors, highlighting its complex involvement in cancer biology. In addition, we co-transfected exogenous E2F1 (Flag-tagged) and mutant p53-R273H (HA-tagged) into H1299 cells, and the co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay showed that E2F1 indeed physically interacted with mutant p53-R273H (Fig. 4L). Similarly, a native interaction of mutant p53 and E2F1 was found in the TP53-mutated LUAD cell line H1975 (p53-R273H) using p53 and E2F1 antibodies in both directions, without the use of transfection (Fig. S6o). Furthermore, in H1299 cells, E2F1 overexpression significantly reduced the transcriptional activation of CENPF by mutant p53 overexpression (p53-R273H) (Fig. 4M), while in H1975 cells, E2F1 downregulation significantly inhibited the transcriptional inhibition of CENPF by silencing mutant p53 (p53-R273H) (Fig. 4N). As reported in previous research, Extensive crosstalk occurs between the (wild-type) p53 and E2F1, significantly impacting crucial cellular decisions [74]. Mutant p53 could directly recruit E2F1 and transcriptionally mediate gene expression [75]. Therefore, we concluded that mutant p53 could bind E2F1 to interfere with its transcriptional inhibition of CENPF; thus, accumulated CENPF in cancer cells could exert its oncogenic effect in early-stage LUAD.

A Driver mutation comparation analysis of patients with high and low expression of CENPF in TCGA-LUAD database; CENPF expression (B) and relative content of cancer cells (CENPF+) (C) in patients with WT and Mut p53 in two LUAD datasets; CENPF protein content (D) examined by WB and gene expression (E) examined by qPCR after overexpression of hot mutant p53 proteins (R175H and R273H plasmids) in TP53-null H1299 cells; CENPF protein content (F) examined by WB and gene expression (G) examined by qPCR after KD of mutant p53 (R273H) by siRNA in H1975 cells. H transcription factors prediction for CENPF in different transcription factor databases. I CENPF expression (right) and CEBPB (left) examined by qPCR in PC-9 lines after KD of CEBPB (siRNA). J CENPF expression (right) and E2F1 (left) examined by qPCR in PC-9 lines after KD of E2F1 (siRNA). K CENPF expression (right) and MAZ (left) examined by qPCR in PC-9 lines after KD of MAZ (siRNA). L Interaction between exogenous E2F1 and mutant p53-R273H. H1299 cells were co-transfected with indicated constructs (mutant p53 (R273H)-HA and E2F1-Flag). Cellular extracts were immunoprecipitated with antibodies (HA, lane 3 and Flag, lane 4) and immunoprecipitations were performed with antibodies against the indicated proteins. M CENPF gene expression (left) examined by qPCR and protein content (right) examined by WB in H1299 cells after overexpression of mutant p53 (R273H)-HA and E2F1-Flag (plasmids). N CENPF gene expression (left) examined by qPCR and protein content (right) examined by WB in H1975 cells after KD of mutant p53 (R273H) and E2F1 (siRNA). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. N ≥ 3, Data are presented as mean ± SD. The boxplots indicate median (center), 25th and 75th percentiles (bounds of box), and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles (whiskers). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s t test for multiple comparisons test (E, G, I–K, M, N). Wilcoxon rank-sum test (B, C). The chi-square test with the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) method for P value correction (A). CENPF centromere protein F, E2F1 E2F transcription factor 1, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, WT wild-type, Mut mutation type, KD knockdown, WB western blot, qRT-PCR quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, MAZ MYC-associated zinc finger protein, CEBPB CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta.

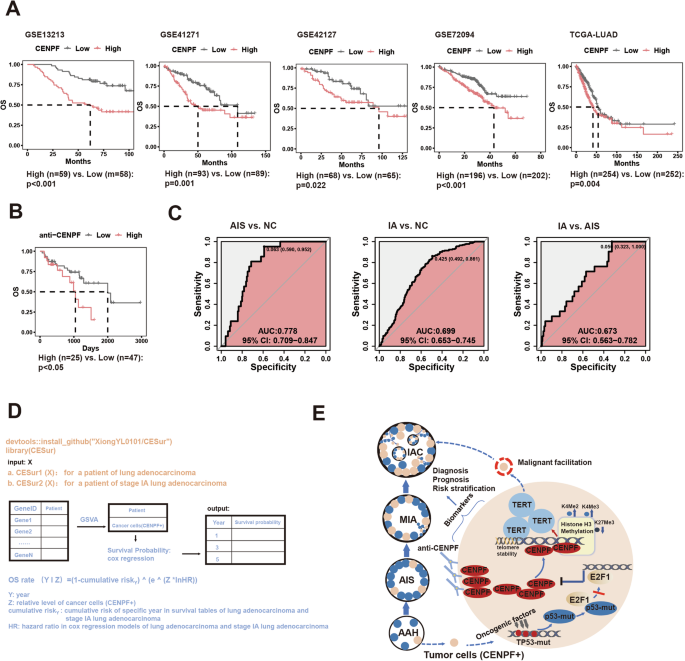

Clinical significance of CENPF in early-stage LUAD, especially stage IA

The clinical significance of CENPF is the key to evaluate its cancer-promoting function. First, we then evaluated the relationship between CENPF expression and malignant clinical features of early-stage LUAD. We found that LUAD patients with high CENPF expression (divided by the median value) had generally poorer OS in five independent datasets (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, high CENPF expression in tumor tissues was an independent predictor of risk for OS in four LUAD datasets with complete clinical information (Fig. S7a). Subsequently, we found that CENPF increased gradually with tumor stage, and the trend was most pronounced in stage I-II tumors in the four LUAD datasets (Fig. S7b). We further investigated the importance of CENPF for earlier stage LUAD, such as stage IA, which is dominated by small nodules and has a prognosis that is always difficult to stratify [1]. We selected two datasets with relatively large numbers of LUAD patients with stage IA disease (GSE72094, n = 150; TCGA-LUAD, n = 131) and divided them into high and low CENPF expression groups according to the median cut-off value. We found that stage IA patients with high CENPF expression had generally poorer OS (Fig. S7c), and CENPF expression was also an independent risk factor for OS in stage IA patients (Fig. S7d). These results suggest that CENPF content can be used as a prognostic risk parameter for early-stage LUAD, especially stage IA disease.

A Association between CENPF expression and OS in five LUAD datasets. B The relationship between serum CENPF autoantibodies and OS of LUAD. C The combined diagnostic effect of serum CENPF autoantibody, CEA, and CYFRA21.1 for distinguish NC from AIS (left), for distinguish NC from stage IA (middle) and distinguish AIS from stage IA (right). D Development a R package (CESur) for clinical application of cancer cells (CENPF+) to predict prognosis of LUAD. E Schematic diagram of mechanisms by which the cancer cells (CENPF+) promote the malignant evolution of early-stage LUAD. The log-rank test and weighted log-rank test (Peto-Peto test) (A, B). CENPF centromere protein F, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, OS overall survival, NC Normal patients, AIS carcinoma in situ, IAC invasive adenocarcinoma.

Serum autoantibodies against tumor antigens play an important role in the clinical evaluation of tumors [76]. Previous studies demonstrated a direct correlation between CENPF autoantibody levels and hepatocellular carcinoma progression, suggesting the potential of CENPF autoantibody as an early diagnostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma [77, 78]. We found that the serum CENPF autoantibody levels in LUAD patients could be used as a predictor of prognosis, and patients with high serum CENPF autoantibody levels had poorer OS (Fig. 5B). We further evaluated the prognostic value of serum CENPF autoantibody levels in early-stage LUAD, especially stage IA disease. Stage IA patients with higher CENPF autoantibody levels had a lower OS; however, significance might occur with extended follow-up due to the high survival rate of stage IA LUAD patients (Fig. S8a). Similarly, classical serum biomarkers (CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CYFRA21-1, Cytokeratin fragment antigen 21-1) of LUAD showed a similar trend in stage IA patients (Fig. S8b, c). We then evaluated the diagnostic value of serum CENPF autoantibody levels in early-stage LUAD. We found that serum CENPF autoantibody levels were progressively increased in early-stage LUAD (normal patients (NC)-AIS-IA) (Fig. S8d); however, no NC-AIS-IA progressively increasing rule was observed for CEA and CYFRA21-1 (Fig. S8f, h). Serum CENPF autoantibody levels could distinguish NC from stage IA and AIS from IA but could not distinguish NC from AIS (Fig. S8e). For CEA, CEA in serum could distinguish NC from IA and AIS from IA but could not distinguish NC from AIS (Fig. S8g). For CYFRA21.1, CYFRA21.1 in serum could distinguish between NC and IA and between NC and AIS but could not distinguish between AIS and IA (Fig. S8i). We conducted combined diagnostic analysis of the above three serum indicators and found that NC and AIS, NC and IA, and AIS and IA could be clearly distinguished after taking the three serum indicators into consideration (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that serum CENPF autoantibody levels can be used as prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers for LUAD, especially stage IA, and the combination with classical markers has a better diagnostic effect.

Finally, we evaluated the role of cancer cells (CENPF+) in the prognostic assessment of early-stage LUAD. In the TCGA-LUAD dataset, patients with high cancer cell (CENPF+) levels had a significantly poorer prognosis (the median content was taken as the cut-off value) (Fig. S9a). We also used this content as a cut-off value and found that in four other LUAD datasets (GSE13213, GSE41271, GSE42127, GSE72094), patients with high cancer cells (CENPF+) levels still had a significantly poorer prognosis, suggesting the universality of this cut-off value (Fig. S9c). Based on the TCGA-LUAD dataset, we plotted a nomogram to predict the OS probability of LUAD based on cancer cell (CENPF+) levels (Fig. S9b). We further evaluated the prognostic role of cancer cell (CENPF+) levels in stage IA LUAD. Due to the small sample size of stage IA LUAD patients in a single dataset, we integrated stage IA patients from five LUAD datasets into one dataset. Before Z transformation, the five datasets showed obvious batch effects (Fig. S9d), while after Z transformation, the batch effect was not serious (Fig. S9e). By cross-validation (k = 4), we found that cancer cells (CENPF+) levels could significantly predict the prognosis of stage IA LUAD patients (Fig. S9f). Based on all samples considered in the survival prediction (Fig. S9g), we also established a nomograph to predict the OS probability of stage IA LUAD based on cancer cells (CENPF+) levels (Fig. S9h). Finally, based on the above models, we established the R package (CESur) for predicting the survival probability of LUAD, especially stage IA patients with bulk transcriptome data, which includes two functions: CESur1: LUAD; CESur2: stage IA, which could be used for clinical application conveniently and economically (Fig. 5D).

In conclusion, mutant p53 binds to E2F1, abrogating its transcriptional repression of CENPF, thereby fostering the accumulation of cancer cells (CENPF+) in early-stage LUAD. High CENPF expression in cancer cells epigenetically activates TERT by modulating histone H3 methylation, sustaining high stemness and proliferative capacity, thereby promoting malignant progression in early-stage LUAD. The detection of CENPF autoantibodies in serum and the abundance of cancer cells (CENPF+) in tumor tissue can serve as valuable biomarkers for assessing the clinical characteristics of early-stage LUAD (Fig. 5E).

Discussion

Early-stage LUAD, mainly characterized by small nodules, has gradually become a common disease in the population, and precise prevention and treatment are urgently needed [1, 2]. Clinical management of early-stage LUAD cannot be generalized due to its heterogeneity in prognosis risk to avoid overtreatment in the low-risk type and undertreatment in the high-risk type [2,3,4,5,6]. Previous studies have differentiated high-risk and low-risk subtypes of stage IA LUAD based on radiological and pathological characteristics. For example, the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) and the West Japan Oncology Group (WJOG) carried out a series of trials to demonstrate that the combination of the proportion of solid components and tumor size was a good indicator to define the invasive degree of stage IA LUAD (such as lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, local recurrence and long-term survival), resulting in a decreased excision extension and extended time for surgery of the low-risk type [4, 10, 79]. Pathological features such as a micropapillary component, solid component, vascular invasion, and spread through air spaces often predict poorer prognosis, which can guide the possibility of benefit from postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy [5, 11, 13]. However, the existing classification criteria, such as the CTR value, are controversial, and the specific quantification of pathological components is also difficult, so other risk classification indicators are still urgently needed [14,15,16].

Molecular classification based on malignant mechanisms has important clinical benefits for the precise treatment of cancer [80]. The progressive evolution of pathological stages from preneoplasia to invasive LUAD is the cornerstone of accurate prevention and treatment of early-stage LUAD [15]. The key cellular-molecular events are an important breakthrough to elucidate the process of cancer evolution, and scRNA-seq technology provides an important research method [81]. Using scRNA-seq technology, we identified a kind of special cancer cells (CENPF+) that accumulated gradually with the progression of early-stage LUAD (AIS-MIA-IAC). Further, we demonstrated the expression of CENPF, the content of cancer cells (CENPF+) in tumor tissue and even CENPF autoantibodies in serum could be used as indicators to evaluate the clinical features of early-stage LUAD.

We next investigated the biological function of cancer cells (CENPF+) in early-stage LUAD. Via biological enrichment of scRNA-seq data, we found that cancer cells (CENPF+) exhibited more aggressive malignant characteristics than other cancer cells in early-stage LUAD. Furthermore, through GSEA, we found that the expression of CENPF was closely related to proliferative potency and stemness maintenance in LUAD tumor tissues, even in stage IA samples, as well as in cancer cells in a single-cell database or in vitro cell lines. CENPF is often used as the surrogated marker for cell proliferation and as the functional and structural unit of the kinetochore complex in the process of mitosis [53]. Is CENPF merely a bystander indicator of malignant features in early-stage LUAD? In recent years, studies have gradually suggested that CENPF has significant carcinogenic potential. In breast cancer, liver cancer, prostate cancer, LUAD and other cancers, abnormally high expression of CENPF indicated poorer prognosis and facilitated diverse malignant characteristics, such as proliferation, metastasis, apoptosis inhibition, and immune escape [78, 82,83,84,85]. Previous studies focused on the relationship between CENPF expression in tissues and the prognosis of LUAD, as well as its role in adenocarcinoma cell lines and xenograft lung cancer model of nude mice [82, 86, 87]. We not only demonstrated that CENPF significantly promotes the proliferative potency and stemness of LUAD cell lines. At the same time, in more advanced tumor research models, the cancer-promoting function of CENPF was systematically demonstrated. Cancer organoids can closely recapitulate the histological features and stereochemical structure of tumors and have gradually become valuable platforms for cancer research [55]. We established organoids derived from stage IA LUAD and demonstrated that CENPF pivotally maintains the stemness of LUAD cells. PDX model can accurately reconstruct the characteristics of tumor microenvironment, considering to being an admirable preclinical model for cancer [56]. In addition, in a cell line or PDX mouse model of LUAD, we proved the oncogenic potential of CENPF in vivo. Furthermore, we demonstrated that silencing CENPF could impede cancer initiation and formation in a spontaneous LUAD mouse model. Therefore, CENPF may be a driver gene rather than just a companion gene in the malignant progression of early-stage LUAD. However, the current classical molecular mechanisms of CENPF like functioning in kinetochore complex cannot enough explain the oncogenic effect of CENPF, especially on stemness maintenance and cancer initiation demonstrated above. The detailed molecular mechanisms of CENPF in malignant progression of early-stage LUAD needs to be explored in depth. It is worth noting that the animal models used in this study are conventional and classic models of LUAD, without distinguishing between stages of LUAD. Subsequent work will focus on developing specific models of early-stage LUAD (stage IA) to more accurately explore the role of CENPF in the evolution of early-stage LUAD.

Through transcriptome sequencing of the CENPF-KD model and corresponding molecular experiments, we found that silencing CENPF significantly decreases the transcription and protein content of TERT, and the carcinogenic function of CENPF can be affected by the content of TERT. Such effects have also been highlighted in a clinical cohort. TERT is a key molecule that maintains the activity of tumor telomerase and thus maintains the stability of telomeres and is an important prerequisite for the infinite proliferation, stemness maintenance and other malignant characteristics of cancer cells [88,89,90]. Through IP experiments and proteomics analysis, we further found that CENPF probably mediates epigenetic modification by interacting with histone H3. Considering the important regulatory modes of TERT by methylation and acetylation of histone H3 [63], we further demonstrated that CENPF interfered with methylations of histone H3 (repression of H3K27Me3, a common mark of inactive chromatin [66], and activation of H3K4Me2 and H3K4Me3, associated with active genes [64, 65]) to activate TERT transcription. In clinical LUAD samples, we also demonstrated a close relationship between CENPF and TERT, as well as the clinical value of the CENPF-TERT axis. In fact, in addition to being a critical assembly protein of the chromosomal centromere and kinetochore, CENPF possesses a complex structure and diverse functions, and its abnormal expression or mutation is closely related to many kinds of diseases, such as human ciliopathy, microcephaly phenotypes, stromme syndrome and myocardiopathy [53, 91,92,93,94]. Therefore, we comprehensively showed that CENPF mediates methylations of histone H3 to transcriptionally activate TERT, thus promoting early-stage LUAD progression.

Finally, we investigated the regulatory mechanism of high CENPF expression, or accumulation of cancer cells (CENPF+) in early-stage LUAD. We found that LUAD patients with high CENPF expression or high cancer cells (CENPF+) levels had more TP53 mutations. In fact, TP53 mutation has been reported to be a driver mutation in early-stage LUAD progression [17, 19, 69], which is consistent with the oncogenic function of CENPF in early-stage LUAD. We further demonstrated that the hotspot mutation (p53-R273H) of TP53 was possibly the main reason for high CENPF expression in LUAD. How does TP53 mutation specifically regulate CENPF content? Previous studies suggest that mutated TP53 proteins can regulate the transcription of tumor-related molecules by themselves and/or by recruiting transcription factors [71]. Via transcriptional prediction and molecular experiments, we found that E2F1 is a new transcription factor that inhibits CENPF transcription. It has also been reported that mutant TP53 protein can directly recruit E2F1 to transcriptionally regulate target genes [75]. We indeed demonstrated that the mutant TP53 protein can bind to E2F1 and interfere with its transcriptional inhibition of CENPF. E2F1 has intensive functional diversity and conflicting nature in tumors, depending on its molecular status or cell context and tumor stage [72, 73]. This study once again confirmed the complex function of E2F1 in tumors, possibly exhibiting tumor repression function, to some extent, in early-stage LUAD. Therefore, we deduced that the widely mutated TP53 protein in early-stage LUAD cells upregulates CENPF expression by binding to E2F1 and blocking its transcriptional inhibition of CENPF, thus allowing cancer cells (CENPF+) accumulation to exert its malignant effects for early-stage LUAD progression.

Conclusion

In summary, the accumulation of cancer cells (CENPF+), triggered by TP53 mutations, exhibits robust proliferative and stem-like properties. These features collectively promote the malignant progression of early-stage LUAD, offering a promising diagnostic marker and therapeutic target for precision medicine approaches in LUAD.

Responses