Cervical mucus in linked human Cervix and Vagina Chips modulates vaginal dysbiosis

Introduction

The cervicovaginal fluid that covers the surface of the vaginal epithelium is essential to women’s health and reproductive functions because it serves as a selective barrier that protects against environmental pathogens1,2. This fluid includes mucus that is mainly produced by the cervical epithelium along with vaginal secretions, and it contains a range of cytokines, chemokines, immunoglobulins, and other immune mediators that help to prevent pathogens from crossing this critical mucosal interface. However, the role of cervical mucus in regulating vaginal microbiome composition and its effects on health outcomes has largely remained unexplored3,4,5.

This is important because dysbiotic changes in the composition of the female genital tract microbiome, have been linked to increased susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, preterm birth, and maternal and neonatal infections6,7. This is observed for example in patients with bacterial vaginosis (BV) whose microbiome often contains strict and facultative anaerobes including Garderenella vaginalis. BV is also the most prevalent cause of vaginal symptoms in women with a more than 50% recurrence rate, yet the underlying factors contributing to these conditions remain elusive8.

In this study, we leveraged human organ-on-a-chip (organ chip) microfluidic culture technology to directly explore how cervical mucus secretions influence human vaginal epithelium under both healthy and dysbiotic conditions. To achieve this, we connected two recently described human organ chip models of female reproductive organs. The first is a human vagina-on-a-chip (Vagina Chip) that is lined by primary, hormone-sensitive, vaginal epithelium interfaced with underlying stromal fibroblasts that we have shown recapitulates the pathophysiology of a dysbiotic vaginal epithelium when co-cultured with a G. vaginalis-containing microbiome and that enables analysis of human host-microbiome interactions in vitro9. The second is a human cervix-on-a-chip (Cervix Chip) lined by primary cervical epithelium interfaced with cervical fibroblasts10 that produces abundant cervical mucus with compositional, biophysical, and hormone-responsive properties similar to those observed in vivo. In that past study, we found that varying flow conditions influenced the model to exhibit either endocervical or ectocervical characteristics. In this paper, we focus specifically on mucus production using the endocervical model conditions. To model and study the effect of cervical mucus on vaginal responses in vitro, we co-cultured a dysbiotic microbiome in the human Vagina Chip in the presence or absence of mucus-containing effluents that were transferred from the epithelial channel of human Cervix Chips. These studies revealed that human cervical epithelial secretions exert immunomodulatory effects and protect the vaginal epithelium against a dysbiotic microbiome by reducing innate inflammatory responses and inhibiting the growth of G. vaginalis bacteria, thereby reducing vaginal cell injury.

Results

Modulation of innate immunity in Vagina Chips by mucus-containing effluents from Cervix Chips

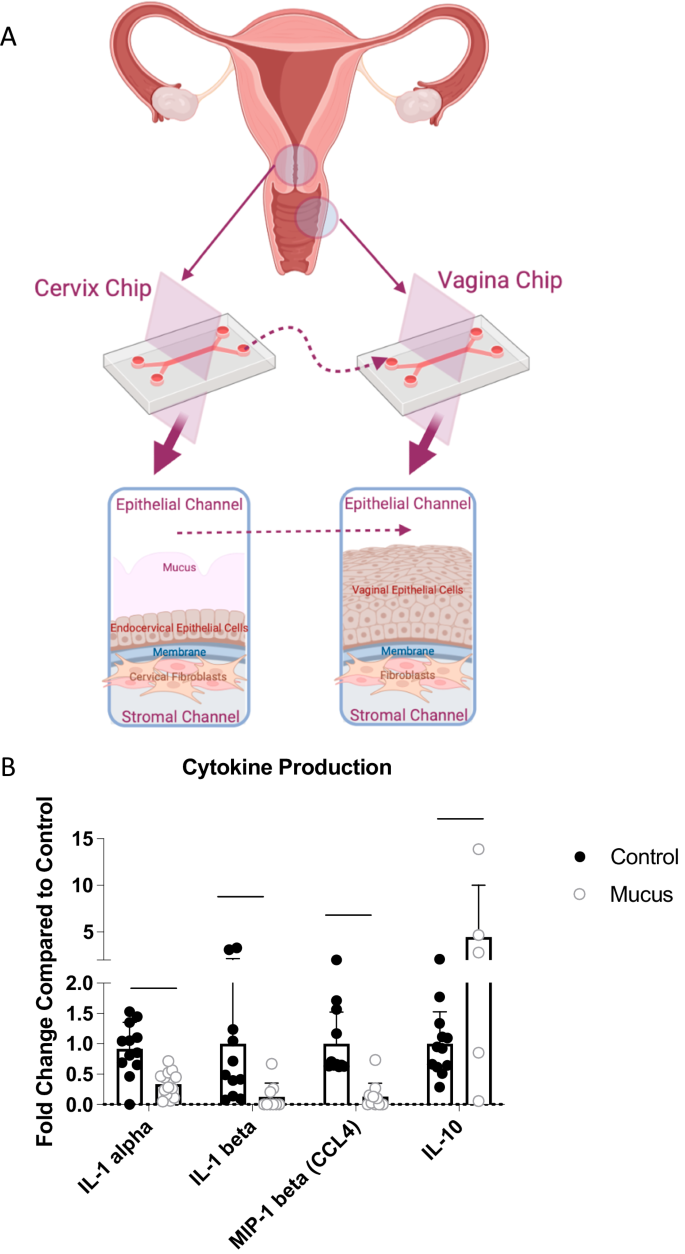

We recently described a human Vagina Chip lined by primary human vaginal epithelium interfaced across an extracellular matrix (ECM)-coated porous membrane with underlying stromal fibroblasts that enables analysis of human host-microbiome interactions in the vaginal microenvironment9, as well as a human Cervix Chip containing primary cervical epithelium interfaced with stromal cervical fibroblasts that produces cervical mucus with physical and chemical properties similar to those observed in vivo10. Here, we collected mucus-containing effluents from the epithelial channel of the Cervix Chip (‘cervical chip mucus’ containing 4.01 ± 3.04 mg/mL of mucus glycoproteins) for 7 days and then perfused it through the epithelial channel of a Vagina Chip to simulate the natural flow of mucus in the reproductive tract in vivo (Fig. 1A). Presence of this mucus in the Vagina Chip induced statistically significant decreases in secretion of multiple relevant proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1α (IL-1α), IL-1β, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1β (MIP-1β), accompanied by a concomitant increase in anti-inflammatory IL-10 protein production after 24 h of exposure compared to control Vagina Chips without mucus (Fig. 1B). These results demonstrate that the mucus-containing fluids produced by human cervical epithelium in Cervix Chips in vitro can directly influence the vaginal epithelium and result in suppression of cytokine production, even in the absence of immune cells.

A Schematic diagrams of Cervix and Vagina Chips and the transfer of cervical mucus between chips (Created with BioRender.com). B Cytokine protein levels for IL-1α, IL-1β, MIP-1β, and IL-10 measured in effluents of Vagina Chips cultured with (light gray bars) without (dark gray bars) cervical mucus for 1 day. Each data point indicates one chip; data shown are from 3 different experiments and are presented as mean ± sd; significance was calculated by unpaired t-test; ***P < 0.0001; **P < 0.001.

Modulation of the dysbiotic vaginal microbiome by introducing cervical mucus into the Vagina Chip

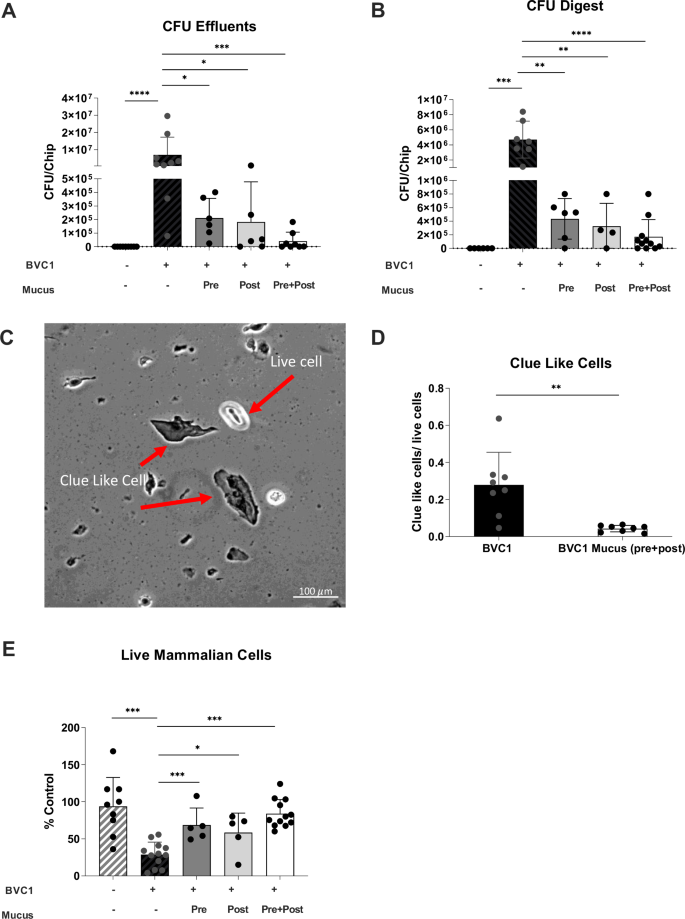

We next studied the effects of cervical mucus on a dysbiotic (non-optimal) vaginal microbiome in Vagina Chips by inoculating them with a consortium containing G. vaginalis E2 and E4 combined with P. bivia BHK8 and A. vaginae (BVC1; ~105 CFU/chip) on day 14 of Vagina Chip culture in the presence or absence of mucus-containing effluents from the Cervix Chip. Interestingly, the presence of human cervical mucus inhibited the consortium’s ability to colonize the vaginal epithelium and thrive on the Vagina Chip. The total number of CFU of live non-adherent bacteria in the effluents of the vaginal chip epithelial channel collected over 72 h of infection (Fig. 2A) and the number of live adherent bacteria in Vaginal Chips digests at the end of the culture (Fig. 2B) were significantly reduced whether the Vagina Chips were pretreated with cervical mucus effluents for one day before microbiome introduction, the mucus was added after the introduction of microbiome, or if the mucus was added one day before the bacteria and present continuously for the following 3 day culture.

Vaginal epithelium cultured on-chip for 72 h in the absence (Control: gray with stripes bars) or presence of BVC1 consortium (black bars) perfused either with media alone or with mucus-containing effluents from Cervix Chips that were added 1 day prior to the addition of bacteria (Pre; dark gray bar), 1 day after BVC 1 addition (Post; light gray bar), or continuously for the entire 3-day culture starting 1 day prior to addition of bacteria (Pre+Post; white bar). A Total non-adherent bacterial cell number (CFU) per chip determined by quantification of bacteria collected in effluents from the apical epithelial channel during 72 h of co-culture with BVC1 in Vagina Chips. B Total adherent CFU/chip determined by quantification of bacteria retained within epithelial tissue digests after 72 h of culture. C Bright-field microsopic image showing Clue-like cells and live epithelial cells using Trypan blue stain. D Ratio of Clue-like cells to live cells detected as described in (C). E Quantification of vaginal epithelial cell injury (percent cell viability) assessed by calculating the number of live cells relative to control using Trypan blue exclusion assay. In all graphs, results were obtained from at least 2 different experiments; each data point indicates one chip. Data are presented as mean ± sd; significance was calculated by unpaired t-test; ***P < 0.0001; **P < 0.001.

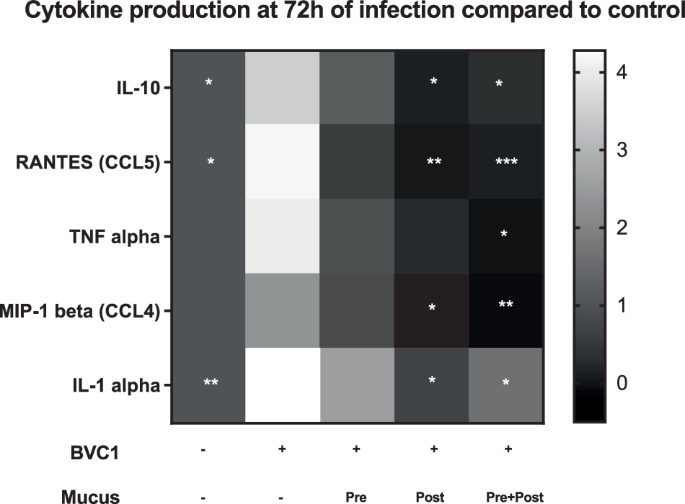

Consistent with these data, we observed a decrease in the number of vaginal epithelial cells with a Clue Cell-like appearance (i.e., covered with bound bacteria)11 in digests of Vagina Chip epithelium with the dysbiotic BVC1 consortium in the presence of cervical mucus (Fig. 2C, D). Not surprisingly, this reduction in bacterial cell number induced by the presence of cervical mucus was also accompanied by a concomitant increase in vaginal epithelial cell viability (retained cell number) (Fig. 2E), as well as significant downregulation of the proinflammatory cytokines, IL-8, IL-10, RANTES (CCL5), TNF-α, MIP-1β, and IL-1α after 72 h of co-culture (Fig. 3). These results demonstrate that Cervix Chip mucus can directly influence the Vaginal Chip epithelium to dampen production of inflammatory cytokines and this correlates with protection of the vaginal epithelium against injury.

Heat map showing the innate immune response of vaginal epithelium cultured on-chip for 72 h in the absence (Control) or presence of BVC1 consortium perfused either without or with mucus-containing effluents from Cervix Chips that were added 1 day prior to the addition of bacteria (Pre), 1 day after BVC 1 addition (Post), or continuously for the entire 3-day culture starting 1 day prior to the addition of bacteria (Pre+Post). IL-10, RANTES(CCL5), TNF-α, MIP-1β, and IL-1α protein levels in the epithelial channel effluents were normalized for cell number. IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-6, MIP-1α, and IP-10 did not show a statistically significant difference between the groups. The grayscale represents the fold-change in cytokine levels relative to untreated control chips, and the statistical analysis was performed by comparing the BVC1 chips (n = 4–10 individual chips for each group from 4 independent experiments; significance was calculated by unpaired t-test ; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared to BVC1).

Suppression of G. vaginalis growth in Vagina Chip effluents

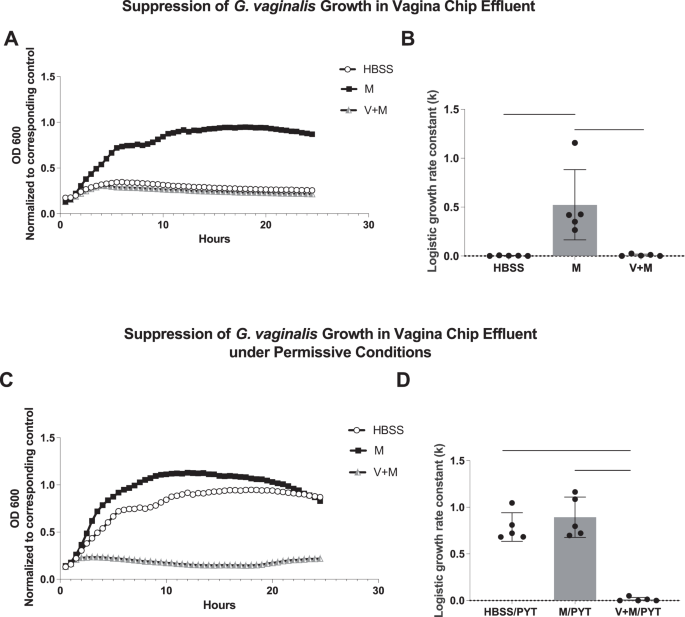

To explore whether cervical mucus acts directly to suppress bacterial cell growth or indirectly by altering vaginal cell physiology, we next compared the growth of G. vaginalis in mucus-containing effluent samples collected from the epithelial channel of control Cervix Chips (perfused with HBSS) versus effluents from Vagina Chips that were perfused with Cervix Chip-derived mucus-containing effluent for 1 day, with the bacteria cultured directly in the HBSS that was used to perfuse the apical channels of our Cervix and Vagina chips as a control. Our results demonstrate that G. vaginalis grew well in the Cervix Chip mucus-containing effluents in 2D culture, but growth was suppressed when cultured in effluents from the Vagina Chip perfused with similar Cervix Chip-derived mucus-containing effluent or in HBSS that lacks critical nutrients (Fig. 4A, B). Importantly, when similar studies were carried out after the addition of 50% bacterial broth to provide optimal nutrient conditions, bacterial growth was restored in the control HBSS effluents, but not in the effluents from the Vagina Chip exposed to Cervix Chip-derived mucus-containing fluids (Fig. 4C, D). These findings suggest that mucus components produced by the Cervix Chip induce the cells lining the Vagina Chip to express factors that suppress G. vaginalis growth.

A G. vaginalis growth in 2D culture wells by optical density (OD) measurement every 30 min for 24 h; (M) within mucus-containing Cervix Chip effluent; (V + M) similar effluent perfused through a Vagina Chip for 1 day; and (HBSS) control. B Logistic growth rate constant (k) for bacterial growth in (A). C Bacterial growth in permissive conditions in which the effluents shown in (A) were supplemented with 50% bacterial broth (PYT). While permissive conditions allowed for growth in the HBSS control group, G. vaginalis growth remained suppressed in the V + M group. D Logistic growth rate constant (k) for bacterial growth in (C). n = 5; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Cervix Chip mucus alters the vaginal secretome

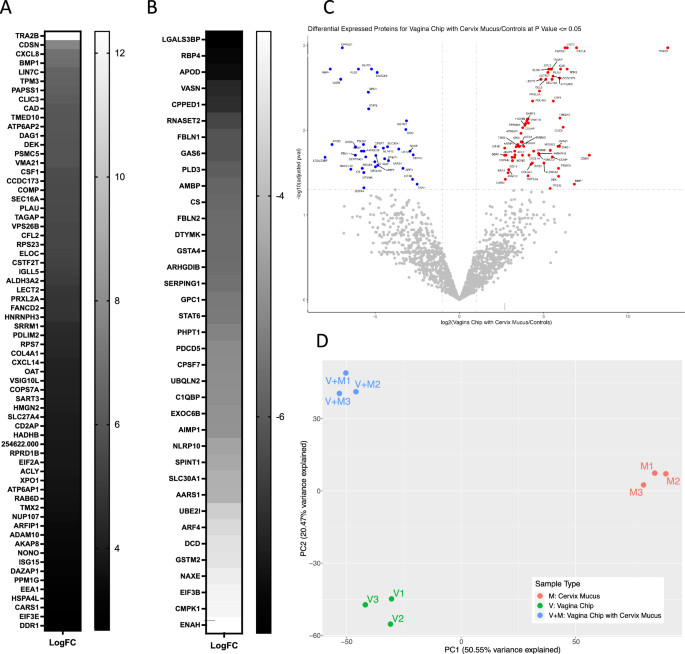

To further explore the effects of cervical mucus on the vaginal epithelium, we conducted mass spectrometry analysis to compare the proteome composition of the Cervix Chip effluent before and after exposure to the Vagina Chip versus the untreated Vagina Chip effluent. Of the 1752 proteins identified (Supplementary table 1), 103 were found to be differentially abundant as determined by fold change ( | log2 fc | > = 1), padj ≤ 0.05) in Cervix Chip effluents that had passed through the Vagina Chip versus either the Cervix Chip effluent or Vagina Chip effluent alone. Significant changes in the expression of multiple proteins were observed, with 64 proteins showing increased expression (Fig. 5A) and 39 proteins showing decreased expression (Fig. 5B), with the most prominent alterations highlighted in a volcano plot (Fig. 5C). Principal component analysis (PCA) of the proteomics data also revealed distinct segregation among these sample groups, indicating notable changes in protein expression in effluents from Vagina Chips exposed to Cervix Chip mucus compared to those from untreated Cervix or Vagina Chips alone (Fig. 5D).

Mass spectrometry analysis of Vagina Chip effluents pre-exposed to Cervix Chip mucus-containing effluent for 1 day (V + M) compared to Vagina Chip effluent alone (V) and Cervix Chip mucus-containing effluent (M). A Upregulated and B Downregulated proteins in (V + M) compared (V) and (M), determined by fold change ( | log2 fc | > = 1, padj ≤ 0.05). C Volcano plot showing differentially expressed proteins in (V + M) compared to (V) and (M). The plot was constructed using the normalized protein expression data with the negative logarithm of the adjusted p value represented on the y-axis and the log2 fold change represented on the x-axis. Each dot on the plot corresponds to a protein, with color coding used to indicate the statistical significance of differential expression. Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method was used for multiple testing correction and plotted adjusted P values. Proteins with a p < 0.05 and fold change >2 are colored red, while proteins with a p < 0.05, and fold change < −2 are colored blue (Gray, proteins with p > 0.05). D PCA plot of the cervix mucus (M, red), vagina chip (V, green) and vagina chip with cervix mucus (V+M, blue) secretome.

Interestingly, using STRING analysis, which incorporates both physical protein-protein interactions and functional associations from various sources (e.g., automated text mining, computational interaction predictions from co-expression, conserved genomic context, databases of interaction experiments, and curated sources of known complexes/pathways)12, we found that 3 of the 39 down-regulated proteins exhibit calcium channel inhibitor activity (PHPT1, AMBP, SLC30A1). Previous research has shown that G. vaginalis strongly induces epithelial calcium influx and contraction13. In addition, 6 of the down-regulated proteins are ECM molecules (LGALS3BP, GPC1, AMBP, SERPING1, VASN, FBLN1, FBLN2), which may play a role in G. vaginalis adhesion and biofilm formation14. Finally, 3 down-regulated proteins are members of the Lipocalin family (AMBP, APOD, RBP4), which is known for its role in regulating inflammation and antioxidant responses15.

The STRING analysis additionally showed that 17 of the up-regulated proteins are RNA-binding proteins (RBPs). Previous studies have highlighted the vital role of RBPs in bacterial replication by binding to and regulating their RNAs16. These proteins also play a crucial role in the immune system response to viral infections by regulating viral RNA stability and translation17. Considering that BV increases susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections, including viral infections, these findings further support the potential involvement of RBPs in the immune response within the reproductive tract. Twenty-five proteins related to the male reproductive system were also found to be upregulated. This finding is significant because past studies have established a notable link between BV and infertility6. For instance, one of the proteins identified, CSTF2T, has the potential to contribute to sperm adhesion to the zona pellucida18 while the also identified TMED10 protein may be involved in sperm capacitation and the acrosome reaction19.

Importantly, exposure of the Vagina Chip to cervical mucus also resulted in enhanced production of potential antimicrobial proteins PLAU and WASF2. PLAU is a serine protease with immunomodulatory functions20 and WASF2 is a member of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein family that regulates autophagy and inflammasome activity21. One of the prominent down-regulated proteins, GNS, is an N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase. This is interesting because BV is often associated with the breakdown of mucins, which are necessary for these dysbiotic bacteria to colonize the vagina22. Thus, downregulation of GNS could contribute to the inhibition of dysbiotic bacterial growth we observed by increasing glycoprotein sulfation and thereby preventing mucin degradation.

Potential role of exosomes as mediators of the effects of cervical mucus on the Vagina Chip

Exosomes, which are small extracellular vesicles containing nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins, play a significant role in intercellular communication in the female reproductive tract by modulating the immune system and promoting tissue repair23. This is accomplished by presenting antigenic peptides, regulating gene expression through exosomal miRNA, and inducing differential signaling through exosomal surface ligands. Importantly, when we carried out STRING analysis of the proteins differentially expressed in Vagina Chip effluents exposed to Cervix Chip mucus, we found that a significant proportion of the differentially expressed proteins were associated with exosomes. Specifically, 23 out of 37 down-regulated proteins and 17 out of 64 upregulated proteins were found to be linked to extracellular exosomes. Notable among the upregulated proteins were DDR124 and COMP25, which regulate cellular adhesion to the ECM and its remodeling, subsequently influencing bacterial adhesion26. Conversely, among the down-regulated proteins, 5 ECM proteins (AMBP, FBLN1, GPC1, LGALS3BP, and SERPING1) were identified, which may also influence bacterial adhesion. Interestingly, SERPING1 functions as a regulator of the complement system27, and three of the down-regulated proteins (AMBP, SERPING1, and SPINT1) belong to the Kunitz family of serine protease inhibitors that are involved in coordinating inflammation28.

Cervicovaginal antimicrobial peptides

Additionally, we identified 12 antimicrobial peptides in the Cervix Chip and Vagina Chip effluents (Table 1). Of these, 6 (Dermcidin, Ubiquicidin, Chemerin, Acipensin 6, hSAA1, and Psoriasin) were present in both Vagina and Cervix Chip effluents, 1 was solely produced by the Vagina Chip (KAMP-19), and 5 were exclusively produced by the Cervix Chip. No antimicrobial peptides were specifically induced in Vagina Chips exposed to Cervix Chip effluents. The Cervix Chip-derived antimicrobial peptides include Histone H4, Histone H3, CXCL1, BHP, and Chromacin. Histones and their fragments have a variety of antimicrobial actions and functions, including bacterial cell membrane permeabilization, penetration into the membrane followed by binding to bacterial DNA and or RNA, binding to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and neutralizing its toxicity, and entrapping pathogens as a component of neutrophil extracellular traps29,30. It is noteworthy that P. bivia, which was included in our bacterial consortium, has been shown to produce high concentrations of LPS31. CXCL1 also inhibits the growth of E. coli and S. aureus in vitro32 and BHP impedes growth of M. luteus, S. epidermidis, and several fungi (e.g., C. albicans, S. cerevisiae, and A. nidulans)33, while Chromacin suppresses the growth of Bacillus megaterium and Micrococcus luteus34.

Comparison of mucus characteristics and immune responses across different cervical donors

To assess the generalizability of our results, we compared mucus samples from two different cervical donors (Supplementary Fig. 1). We observed comparable mucus glycoprotein concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 1A) as well as similar levels of cytokine proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1B) measured in effluents from Cervix Chips derived from two different donors. The number of non-adherent bacterial cells (CFU) per chip, determined by quantifying bacteria collected in effluents from the apical epithelial channel during 24 h of co-culture with BVC1 in Vagina Chips, was also comparable between the two donors (Supplementary Fig. 1D). However, the innate immune response of vaginal epithelium cultured on-chip for 24 h in the presence of the BVC1 consortium perfused with mucus-containing effluents from different Cervix Chip donors, exhibited a slightly different profile, as illustrated in the heat map (Supplementary Fig. 1C).

Discussion

These data show that mucus-containing effluents from human Cervix Chips suppress the growth of dysbiotic microbiota, associated inflammation, and epithelial cell injury in human Vagina Chips. By analyzing the differentially abundant proteins in the secretome of Vagina Chips following treatment with Cervix Chip effluents, we identified multiple proteins that may contribute to this protective response and that potentially could be used as clinical biomarkers for monitoring female reproductive tract health.

Maintaining homeostasis is crucial for the health of epithelial barriers, which can be disrupted during infection or injury. Inflammation plays a vital role in supporting the body’s defense against pathogens, promoting tissue healing, and restoring homeostasis35. However, chronically high levels of proinflammatory cytokines that undermine normal protective immune signals have been linked to an imbalanced microbiome and compromised epithelial cell stability. This study presents evidence that communication between cervical and vaginal tissues in the lower reproductive tract via transfer of cervical mucus-containing secretions helps to suppress vaginal inflammation in the presence of a dysbiotic microbiome. A growing body of clinical evidence suggests that medical procedures, such as cervical excision, may disrupt the crucial communication between cervical and vaginal epithelium, leading to changes in the composition of the vaginal microbiome36, 37. Our results support this observation and suggest that it is a direct effect of reducing cervical mucus transfer to the vagina, which could only be studied directly using this type of engineered in vitro model.

The recurrence of abnormal vaginal flora after treatment of BV (e.g., with metronidazole) is commonly detected in most women8, however, the underlying factors contributing to these recurrences remain elusive. In our past publications (9,10), we assessed bacterial infection in female reproductive tract organ chips and found that although bacteria can grow in the Cervix Chip, bacterial engraftment was significantly higher in the Vagina Chip. The results of the present study suggest that changes in cervical mucus levels may further impact the susceptibility of the vaginal epithelium to engraftment by bacteria that are associated with BV. Therefore, an imbalance in the cervicovaginal mucus may be a possible contributing factor to the high rate of BV recurrence. In this context, it is important to note that we identified five cervical antimicrobial peptides that appear to play a role in the antimicrobial effects we observed on-chip. These findings suggest that interactions between antimicrobial peptides and the host vaginal epithelium can enhance innate immune protection against dysbiotic flora.

Immune effectors and specialized stromal cells at epithelial surfaces produce cytokines and antimicrobial defenses to orchestrate tissue repair and minimize opportunistic infections. Exosomes can act as mediators for this form of inter-tissue communication. We identified 40 exosomal proteins produced by vaginal epithelium that were modulated by exposure to cervical mucus produced in the human Cervix Chip. Human cervicovaginal exosomes have been previously shown to be part of the female innate defense system and to protect against HIV-1 infection38 as well as bacterial toxins39. Exosomes are also currently being explored as potential therapeutic agents and drug delivery vehicles. Thus, the ability to study the role of exosomes in host-microbiome interactions in the female reproductive tract in vitro using the human organ chip models described here may facilitate the development of novel treatments for vaginal dysbiosis as well as other conditions of the female reproductive tract.

Our study has important clinical implications as it has the potential to identify new targets for diagnosis and treatment of vaginal disorderss. Identifying patients with a high likelihood of recurrent vaginal dysbiosis can help to customize their treatment plan and prevent complications. In this study, we identified multiple proteins and antimicrobial peptides that may contribute to the protective response against dysbiotic microbiota and associated inflammation and injury to the vaginal epithelium. These proteins and peptides could potentially be used as clinical biomarkers for monitoring the health of the female reproductive tract health in the future. Several proteins we identified (e.g., TPM3, PLAU, ALDH3A2, GAS6, DTYMK, SERPING, STAT6, CMPK1) are known to be targeted by existing approved drugs (Progesterone, Urokinase, Disulfiram, Warfarin, Zidovudine, Rhucin, Indomethacin, and Gemcitabine, respectively). Thus, if these molecules actively contribute to the BV phenotype, one or more of these therapeutics could be added to current clinical regimens.

Our results show the value of human organ chip technology for studying vaginal health and diseases of the female reproductive tract. However, further research is needed to evaluate the effects of these compounds as well as modulators of the other putative targets we identified for maintaining vaginal homeostasis and a healthy microbiome.

While the human Vagina and Cervix Chips used in this study replicate many physiological and pathophysiological features of the female reproductive tract, we did not incorporate immune cells. As these cells play a crucial role in mounting antibacterial immune responses, the model would be strengthened by incorporating them in the future. Additionally, this study is based on single-donor data, and we acknowledge that biological replication across multiple donors is essential to enhance the generalizability of our findings. While this study provides initial insights and we observed comparable effects on bacterial growth across donors, the variability seen in cytokine production indicates that additional donors are needed to confirm the consistency of protein expression changes across a broader population.

This study highlights the crucial role that cervical mucus plays in maintaining vaginal health and preventing dysbiosis-associated changes. Our results directly demonstrate that cervical mucus-containing secretions can suppress the growth of dysbiotic microbiota as well as associated inflammation and epithelial cell injury in the human Vagina Chip. We also identified several proteins and antimicrobial peptides that could serve as clinical biomarkers for monitoring female reproductive tract health and potentially be targeted for the treatment of vaginal dysbiosis. This study also sheds light on the potential role of exosomes in inter-tissue communication and immune protection against dysbiotic flora in the female reproductive tract. In addition, these findings could have important clinical implications, particularly for identifying patients with a high risk of recurrent dysbiosis and customizing their treatment plans. Further research is needed to evaluate the effects of modulating the potential molecular mediators we identified on maintaining healthy vaginal microbial homeostasis. However, these findings provide further evidence that human organ chip models provide a valuable tool for studying host-microbiome interactions in the female reproductive tract as well as be useful for identifying potential clinical biomarkers and therapeutic targets for patients with vaginal dysbiosis and other related conditions.

Methods

Human Vagina Chip culture

The Human Vagina Chip was cultured as previously described (36434666). Briefly, microfluidic two-channel co-culture organ chip devices (CHIP-S1TM) were obtained from Emulate Inc. (Boston, MA). The Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane was coated with collagen IV (30 μg/mL) (Sigma, cat. no. C7521) and collagen I (200 μg/mL) (Corning, cat. no. 354236) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, ThermoFisher, cat. no. 12320-032) in the apical channel. The basal channel was coated with collagen I (200 μg/mL) (Corning, USA) and poly-L-lysine (15 μg/mL) (ScienCell, Cat# 0403(. Primary human uterine fibroblasts (ScienCell Research Laboratories, cat. no. 7040) were then seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL in the basal channel and human vaginal epithelial cells (Lifeline Cell Technology, cat. no. FC-0083; donors 05328) were seeded at a density of 3 × 106 cells/mL in the apical channel. Chips were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 under static conditions until the cells formed a uniform monolayer. Chips were then connected to the culture module instrument (ZOË™ CULTURE MODULE, Emulate Inc., USA) and placed under flow conditions. Vagina Chips were cultured using a periodic flow regimen in which vaginal epithelium growth medium (Lifeline, Cat# LL-0068) was perfused through the apical channel for 4 h/day at 15 μL/h. The basal channel was perfused continuously with fibroblast growth medium (ScienCell, Cat# 2301) at 30 μL/h. After 5–6 days, the basal medium was replaced with an in-house differentiation medium9 for eight days following the same intermittent and continuous perfusion regime in the apical and basal channels, respectively. The apical medium was replaced with customized Hank’s Buffer Saline Solution (HBSS) Low Buffer/+Glucose (HBSS (LB/ + G), and the basal medium was replaced with antibiotic-free differentiation medium for one day followed by three days of microbial co-culture as described below.

Human Cervix Chip culture

Human Cervix Chips were cultured as previously described (Izadifar et al., 2023, BioRxiv). Briefly, microfluidic two-channel co-culture organ chip devices (CHIP-S1TM) were obtained from Emulate Inc. (Boston, MA). The PDMS membrane was coated with 500 μg/mL collagen IV (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. no. C7521) in the apical channel and with 200 μg/mL Collagen I (Advanced BioMatrix, Cat. no. 5005) and 30 μg/mL fibronectin (Corning, Cat. no. 356008) in the basal channel. Primary cervical fibroblasts (0.65 × 106 cells/mL, P5,isolated from hysterectomy cervical tissues) were seeded on the basal side followed by seeding primary cervical epithelial cells (1.5 × 106 cells/mL, P5, LifeLine Cell Technology Cat# FC-0080) on the apical side. After seeding, respective chip media were refreshed for each channel and the chips were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 under static conditions overnight. Chips were then connected to to a ZOË™ culture module instrument and cultured using a periodic flow regimen in which cervical growth medium was flowed through the apical channel for 4 h/day at 30 μL/h while fibroblast growth medium was continuously perfused basally at 40 μL/h. After five days the apical medium was replaced by HBSS (Thermo Fisher, cat. no. 14025076) while epithelial cells in the apical channel were fed across the membrane via the basal channel with differentiation medium consisting of cervical epithelial medium (LifeLine Cell Technology, Cat. no. LL-0072) supplemented with 5 nM estradiol-17β (E2) (Sigma, Cat. no. E2257) and 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid (ATCC, Cat. no. PCS-201-040). On day 2 of differentiation the apical medium was replaced by HBSS with low buffering salts and no glucose (HBSS (LB/-G) at pH ~5.4 and cultured for five additional days.

Mucus collection from Cervix Chips

Cervix Chip mucus was collected daily in apical channel effluents for 7 days starting on day 4 of differentiation. During the collection period, the basal channel was continuously perfused with antibiotic- free differentiation medium at a volumetric flow rate of 40 μL/h. The apical channel was perfused with HBSS (LB/-G) for 4 h/day at 40 μL/h and the collected effluents were stored at −80 °C until the end of the experiment. Before introduction to the Vagina Chip, 5.56 mM D-glucose (Sigma, cat. no. G7021) was added to the Cervix Chip mucus effluents to match the glucose concentration to that of the HBSS control medium.

Culture of a BV-associated dysbiosis consortium in Vagina Chips

In BV-associated dysbiosis, Gardnerella species are typically found as dominant bacteria7 accompanied by other frequently found taxa, such as Prevotella species and Fannyhessea species40. To mimic the ecology of BV-associated dysbiosis, we utilized BVC1, which is a BV-associated dysbiosis consortium containing Gardnerella vaginalis E2, Gardnerella vaginalis E4, Prevotella bivia BHK8, and Fannyhessea vaginae. The Gardnerella isolates used in this study were selected because they represent distint genomic groups, exhibit phenotypic diversity in vitro, and were also co-resident, meaning that they were co-isolated from a single participant in the UMB-HMP study42. P. bivia and A. vaginae are prevalent species in BV-associated dysbiosis. The two strains used in this study were co-resident, isolated from a single participant in the Females Rising Through Education Support and Health study41. The apical channel of each Vagina Chip was inoculated with ~2.5 × 104CFU of each bacterium/chip and then chips were incubated statically at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 20 h before starting flow using a Zöe culture module. The basal channel was continuously perfused with in-house antibiotic-free differentiation medium and the apical channel was perfused for 4 h/day with customized HBSS (LB/ + G) medium at a volumetric flow rate of 40 μL/h.

Study design

The study was carried out under five conditions: control, BVC1, pre-treatment, post-treatment and pre+post treatment. Vaginal epithelium was cultured on-chip for 72 h in the absence (Control) or presence of BVC1 consortium with or without cervical mucus. In the Mucus Pre-treatment group, cervical mucus was used as the apical medium for 24 h before BVC1 infection, followed by the use of customized HBSS Low Buffer/+Glucose (HBSS (LB/ + G)) for 72 h as the apical medium. In the Mucus Post-Treatment group, cervical mucus was used as the apical medium beginning 24 h after BVC1 infection and continuing for the duration of the experiment (96 h). In the Mucus pre+post treatment group, cervical mucus was used as the apical medium for 24 h before BVC1 infection, and for 72 h during BVC1 co-culture. All experiments were conducted using Vaginal and Cervix Chips technical replicates of primary cells from a single donor, except for data shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, which compared results from chips created with cells from two different primary donors.

Bacterial enumeration from Vagina Chip co-culture

To enumerate all cultivable bacteria in the effluents, effluent samples (50 μL) were collected at 24, 48, and 72 h. Effluent samples from Vagina Chips containing BVC1 consortia were plated on Brucella blood agar (with hemin and vitamin K1) (Hardy, cat. no. A30) at 37 °C under completely anaerobic conditions. After 48 h incubation, CFU/chip was calculated for each sample. To enumerate all cultivable bacteria engrafted in the Vagina Chip, the whole epithelial cell layer was digested for 1 h with 1 mg/mL collagenase IV (Gibco, cat. no. 17104019) in TrypLE (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 12605010). Cell layer digests were diluted and processed in the same way as effluent samples and CFU/chip was calculated for each chip digest.

Analysis of cytokines and chemokines

Samples (50 μL) of apical effluents from Vagina Chips 72 h post bacterial infection were collected and analyzed for a panel of cytokines and chemokines, including TNF-α, IFN-y, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-8, IL-6, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IP-10, and RANTES using custom ProcartaPlex assay kits (ThermoFisher Scientific). The amount of cytokines per chip was calculated by multiplying the concentration by the chip effluent volume, and the fold change was determined relative to the control. Analyte concentrations were determined using a Luminex 100/200 Flexmap3D instrument coupled with Luminex XPONENT software.

Protein extraction and mass spectrometry

Proteins in the Cervix Chip effluents obtained either before or after exposure to the Vagina Chip were analyzed and compared to proteins in effluents from untreated Vagina Chips. Sample digestion: Samples were run through a 50 kDa filter (Amicron Ultracel, Merck Millipore, Ireland) and digested according to the manufacturer’s protocol for 1 h at 50 °C by Trypsin Platinum (Promega, WV), and digested material was dried in a Speedvac (Eppendorf, Germany). Mass spectrometry: Each sample was resolubilized in 10 µL of 0.1% formic acid. Single LC-MS/MS was performed on a 240 Exploris Orbitrap (ThermoScientific, Germany) equipped with a NEO nano-HPLC pump (ThermoScientific, Germany). Peptides were separated onto a micropac 5 cm trapping column (Thermo, Belgium) followed by a 50 cm micropac analytical column (ThermoScientific, Belgium). Separation was achieved by applying a 5–24% ACN gradient in 0.1% formic acid over 90 min at 250 nL min−1. Electrospray ionization was achieved at 1.8 kV with an electrode junction (PepSep, Denmark) at the end of a microcapillary column with a stainless-steel 4 cm needle (ThermoScientific, Denmark). The Exploris Orbitrap was operated in data-dependent mode, and the mass spectrometry survey scan was performed at 450–1200 m/z and a resolution of 1.2 × 105, followed by selection of the ten most intense ions (TOP10) for HCD-MS2 fragmentation. For each HCD MS2 scan, the fragment ion isolation width was 0.8 m/z, AGC was 50,000, maximum ion time was 150 ms, normalized collision energy was 32 V and an activation time of 1 ms.

Data analysis: Raw data were analyzed with Proteome Discoverer 3.0 (Thermo Scientific, CA) software. Assignment of MS/MS spectra was performed using the Sequest HT algorithm by searching the data against a protein sequence database including all entries from the Human Uniprot database (SwissProt, 2019) and full Uniprot bacteria database (SwissProt, 2022) as well as known contaminants such as human keratins and common lab contaminants. Sequest HT searches were performed using a 15 ppm precursor ion tolerance requiring each peptide N-/C terminiusto adhere with Trypsin protease specificity, allowing up to two missed cleavages. For searches, methionine oxidation ( + 15.99492 Da) and asparagine and glutamine deamidations (+0.984016 Da) were set as variable modifications as well as N-terminal acetylation of protein termini. A MS2 spectra assignment false discovery rate (FDR) of 1% on the protein level was achieved by applying the target-decoy database search. Filtering was performed using a Percolator (64 bit version)43. For quantification analysis between samples, label-free quantitation mode using Minora detection features of the Proteome Discoverer platform was used. Protein-level data obtained from each TMT channel was subjected to comprehensive analysis in R. After normalizing the dataset using the variance stabilization method, the data were transposed and input into the R prcomp function to perform PCA. To compare the protein expression profiles of the Vagina Chip with Cervix Mucus to Controls, differential expression analysis was then conducted using the R limma package. P-value adjustment for multiple testing correction was performed using the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method. Next, we performed STRING analysis on the identified proteins. This analysis incorporates both physical protein-protein interactions and functional associations from various sources, including automated text mining, computational interaction predictions from co-expression, conserved genomic context, databases of interaction experiments, and curated sources of known complexes and pathways We conducted a comparison of multiple proteins by name and selected Homo sapiens as the organism. In our analysis, we grouped terms by similarity with a threshold of ≥ 0.08 and applied a FDR of < 0.00112.

Statistical analysis

The results presented in this study are based on findings from at least two independent experimental replicates. For each experiment, data points represent the mean values, with the associated standard deviation (s.d.) calculated from a sample size of greater than three organ chips, unless otherwise explicitly noted. To assess statistically significant differences between the means of different experimental groups, an unpaired t-test was utilized. The statistical analyses were rigorously conducted using GraphPad Prism software, version 9.0.2.

Responses