Changing boundaries, distributed control, and implications for transportation sustainability

Introduction

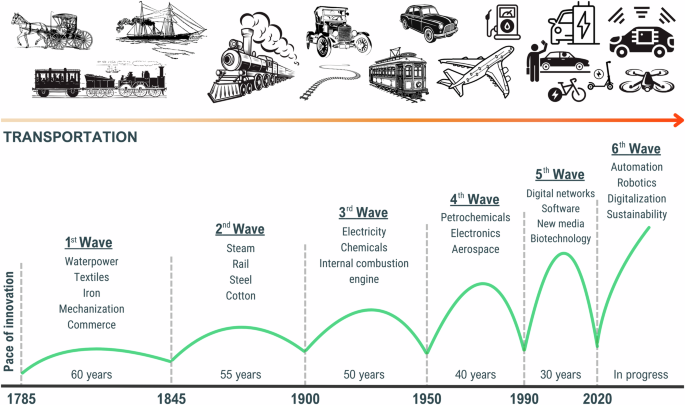

Transportation systems are an integral part of modern society. After thousands of years of relying on walking, horses, and the wind, the industrial revolution enabled people to access immense quantities of energy more rapidly than ever before1. The advent of railroads in the mid-19th century greatly increased transportation speed and required the development of supporting technologies ranging from iron, steel, and engines to time zones and infrastructure bureaucracy2,3. Within decades, railroads were eclipsed by motorized transport (cars and trucks)4. These technological developments are often contextualized within technology waves and the capabilities they create (Fig. 1)5.

The horizontal axis shows the progression of time, while the vertical axis shows the pace of innovation. The dominant technologies during each time period are listed for each wave.

A new wave has emerged in the past half-century through advancements in information technology enabled by cybertechnologies. In the 1960s, automotive manufacturers began integrating microprocessors into vehicles, initially to optimize engine performance through fuel injection6. As a result of accelerating capabilities and decreasing costs, sensors, microprocessors, data storage, and software are now prevalent in vehicles and are being integrated into transportation infrastructure. Smart phones increasingly steer our travel behavior. Modern cars contain thousands of microprocessors, used not just for fuel injection, but to enable an often opaque suite of capabilities including satellite and cellular communication of data7. Pressing the gas pedal now involves software. Microprocessors are integral to fuel economy advancements, electric vehicles, safety improvements, and navigation software8,9. The integration of cybertechnology has allowed slow-moving legacy infrastructure to keep up with the rapid changes in how we use transportation. It has also led to smarter, increasingly automated vehicles.

Treating this integration as an extension of legacy technologies fails to recognize the fundamental transformation underway. A critical perspective is needed to recognize that transportation systems are becoming part of a complex Cognitive Ecosystem (CE). This ecosystem encapsulates technologies, services, institutions, products, and data that directly support emergent cognition that together are changing the nature of transportation systems, how they are used, and who controls services10,11. Here, we adopt a framing of cognition that includes problem-solving, perception, intelligibility, learning, information processing, communication, and decision-making11. We argue the CE will not only serve the transportation system but will also hybridize and control it.

In this perspective, we reimagine our approach to understanding the integration of cybertechnology in the transportation system. We begin by examining how the melding of legacy transportation infrastructure and digital infrastructure is redefining mobility. Here, hybridization refers not to hybrid electric vehicles, but to the diffusing of traditional system boundaries between transportation and other infrastructure. We then discuss distributed control (DC), a paradigm for decentralized, connected decision-making. Finally, we discuss how these shifts caused by the CE require us to move away from traditional normative perspectives on sustainability to new framings that embrace the complexity and uncertainty of the Anthropocene and challenge existing models of the transportation system.

Hybridization

Transportation systems are increasingly integrated with other infrastructure enabled by the CE, creating new interdependencies and enabling novel capabilities. The tandem evolution of the CE and transportation systems will continue to stimulate interconnection with other systems and will require new approaches to management.

Hybridization is driven by new capabilities enabled by the sensors, data, connected technologies, and information processing that make up the CE, and by the changing conditions of the Anthropocene. As society has transitioned to technology-driven services, harnessing information has become a key driver of economic growth12. The advent of low-cost sensors, digital communication networks, and the increasing availability of data and real-time data processing capabilities are impacting physical infrastructure, vehicles, and services that make up the current transportation system and allowing for the growth of more complex, interdependent systems10.

While transportation hybridization continues to evolve as new capabilities emerge from the CE, its effects can already be seen. The power sector and transportation systems once operated largely independently, but electric vehicles (EVs) are intertwining these systems in novel ways. EVs depend on reliable electricity, but the reliability of the power system is impacted by growing electricity demand and charging patterns of EVs13. As major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, the power and transportation sectors face demands to reduce their climate impacts14,15, but their ability to do so is mutually dependent. While EVs can have lower emissions than conventional vehicles if charged with clean electricity16, increased charging demand can also increase emissions from electricity generation17. EVs may have implications for resilience if they are used to provide grid services18 or backup power during outages19. Coordinated efforts are needed to manage their development.

Integrating transportation and communication systems is creating new capabilities for mobility management and environmental sensing. Increased utilization of smart phones and their GPS functions have enabled real-time traffic control through routing services (e.g., Google Maps, MapQuest)20, ride-hailing services (e.g., Uber, Lyft), and new safety measures such as crash detection services21. GPS tracking has enabled the integration of inexpensive sensors with vehicles or smartphones, allowing for mobile data collection related to weather, air quality, UV index, and water quality22,23. Further integration of advanced sensors, computer processing, and GPS into vehicles has enabled the development of autonomous self-driving vehicles (AVs) and automated ride-hailing services. AVs may enhance safety performance and reduce traffic congestion24, and will likely have wide-ranging consequences for the design and operation of the transportation system.

Through cybertechnology integration, transportation infrastructure is increasingly evolving to have multiple functions, some unrelated to mobility. The Stormwater Management And Road Tunnel (SMART) in Kuala Lumpur is used both to regulate vehicular traffic and also to convey stormwater during heavy rains25. Smart signaling and controls steer how traffic and/or water uses the tunnel. Solar roadways are an emerging technology which would allow roads to function not only as conveyors of vehicles but also as electricity generators26. While still developing, the technology has been tested at small scale in China27. The proposed i-11 Supercorridor in the Western United States has been conceptualized as a multi-modal highway corridor improving connections to Mexico and Canada while using right of way for next generation power infrastructure, high-speed fiber optics, and rail in addition to the highway28. As hybridization of transportation systems continues, we expect continued development of multifunction infrastructure.

The integration of transportation with other systems will require re-thinking how hybrid systems are managed. Decisions that were once strictly in the domain of transportation now span multiple infrastructures. For example, determining where to locate EV charging stations will require consideration of more than just the limitations of the transportation system (e.g., traffic patterns, vehicle ranges), as the spatial distribution of EV charging loads has implications for the additional electricity generation and storage needs of the power system13, and the local distribution system, which will require upgrades to support increased power demand from charging29. Vehicle-to-grid technologies will open up new management paradigms for transportation and power system planners who may come to rely on vehicle batteries to support the grid.

The blurring of boundaries between traditionally separate infrastructure systems is already changing the capabilities of the transportation system and how we think about its value. Hybridization will likely accelerate as the CE further penetrates legacy infrastructure and innovates novel transportation functions. Harnessing the data economy and utilizing powerful emerging tools like AI could allow transportation planners and policy-makers to pursue objectives beyond physical mobility by leveraging the capabilities of and synergies with other systems. To realize the potential benefits of these developments, novel approaches to decision-making and management across infrastructure systems are needed.

Distributed control

The advent of the CE has enabled a greater diversity of actors to exert control over transportation infrastructure and services. As a result, governments, NGOs, drivers, hardware makers (e.g., the cloud, super computers), and software companies (increasingly including AI) are now decision-makers. Traditionally, transportation systems have consisted predominantly of two parties: producers (transportation agencies who determine operational goals and establish controls) and consumers (people and businesses that use transportation services). In contrast, with DC there are now additional layers of actors that can exert influence and control over systems. This complexity creates new capabilities, conflicts, and uncertainties in managing transportation systems.

Historically, transportation networks have been largely designed, monitored, and controlled by a small number of authorities: state and federal Departments of Transportation, public and private engineering and planning offices, and large industries (e.g., railroads, airlines). Limited data availability resulted in only the most powerful stakeholders—e.g., public agencies who could gather data from loop detectors and adjust traffic signal timing – having the ability to exert significant control over the system. Adoption of bureaucratic structures in government entities and industry monopolies (e.g., railroads) facilitated institutional lock-in3. Now, increasing data collection and analysis capabilities allow more actors to pursue their own interests within the transportation system. Whereas in the past only a small set of stakeholders had cognition and thus control over the system, today cognitive capabilities are much more diffuse.

As the diffusion of cognitive capabilities changes the nature of control, early examples of how DC is impacting the transportation system are emerging. Power companies are exerting influence through their control of electric vehicle charging. Many electric utilities have special tariffs and rate structures for electric vehicle owners designed to incentivize reduced charging during times of peak power demand and avoid strain on power infrastructure. This control could evolve to be more dynamic, with communications between EVs in the same power network being employed to optimize charging schedules, minimize peak power demand, and respond to electric grid conditions. New actors and approaches are also emerging to manage traffic and congestion. Metropia, a mobile app, was recently developed to reduce congestion in cities through predicting traffic flows based on real-time and historic data and offering incentives to drivers based on route selection and departure time to improve traffic flow30. Increasingly, private companies are also influencing travel behavior, with ride-hail companies like Uber and Lyft causing large decreases in transit use in some areas31.

While consumers and producers of mobility were once mostly separate, the CE has enabled actors to influence both supply and demand of transportation. Actors extract data and value from the transportation ecosystem and use the resulting knowledge to influence mobility patterns. This phenomenon will increasingly occur at micro- and macro-scales, from proximate connected and automated vehicles communicating with each other, to technology companies routing millions of travelers every day. The complexity of the CE makes tracing the origin of information difficult, making it challenging to draw conclusions about the system structure and functioning. Less centralized systems and the complexity of data flows may also lead to additional vulnerabilities and cascading failures, as seen in the 2022 Southwest Airlines crisis32 and the 2024 CrowdStrike incident33.

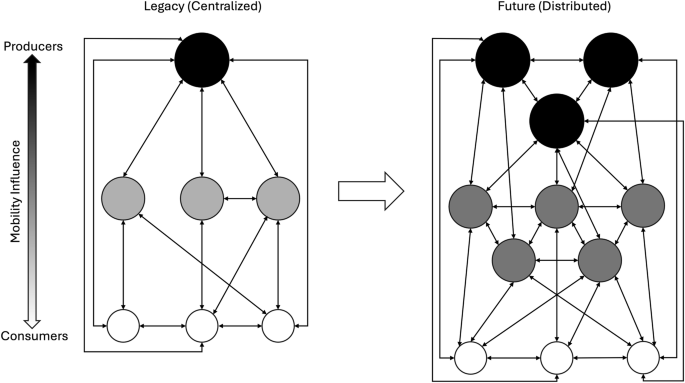

As the CE facilitates a shift from the current centralized regime to the DC regime, more players are expected to emerge with significant influence over mobility production alongside more connections between players (Fig. 2). In the DC regime, governance structures will continuously adapt and reform in response to increased technological capabilities.

Circles represent the actors, and the color represents the position of influence along a mobility producer-consumer spectrum. Players are organized into three tiers: Tier 1 (black, few but powerful) players represent actors with the largest producer influence, including infrastructure managers, tech companies, and rideshare services; Tier 2 (gray, more numerous but less powerful) players represent actors with moderate producer influence including insurance and automobile companies, major transportation industries (rail, airlines, shipping, etc.), and the energy industry; Tier 3 (white, many but weak) players represent actors with primarily consumer influence including individuals and small businesses.

The emergence of DC represents an uncoordinated regime shift in infrastructure governance. What was once an exclusive group of dominant actors with well-defined roles is now expanding into a complex network of individual actors with their own interests. Longstanding actors including public agencies, automobile manufacturers, and major industries remain, but new actors are emerging due to hybridization and integration with the CE. Apple and Google have emerged as major players due to their data collection and navigation systems, as have EV and AV companies, ride-hailing services, and adversaries targeting cybersecurity vulnerabilities10. Some historical actors have expanded their roles, with automobile companies collecting vast amounts of data from vehicles, using it to improve vehicle design and understand the use of their products, and selling it to interested parties like insurance companies34. Data management and ownership will likely be key factors in the distribution of power among actors in the DC regime. These developments obfuscate the influence of the increasing number of actors making decisions.

We consider the shift towards DC through the lens of environmental social dilemma theory, as competition over common pool resources (CPRs)35. In the DC regime, transportation governance negotiates influence over three CPRs: space, time, and the CE. Actors leverage the CE’s data capabilities to extract value from the system, which manifests in manipulating the use of space (the transportation network) and time (travel time). However, unlike most CPRs, data are not limited resources. Many actors create, collect, and manipulate transportation data, greatly increasing the complexity of DC governance leading to the emergence of unpredictable system behaviors. Travel behavior patterns, transportation operations, infrastructure design, and funding and planning decisions are all subject to the influence of the DC regime. Simple governance strategies may no longer be effective. Players have incomplete information, operate at global scales, and have diverse priorities and influence, necessitating the adoption of adaptive governance approaches to leverage the capabilities of the CE while mitigating its negative effects on the environment and society.

How can effective governance emerge from this complexity? The DC regime renders the traditional management role of public transportation agencies obsolete. The government no longer has primary authority due to the inability to explicitly control such a complex, adaptive system. Different actors have distinct ideas about what characterizes an “effective” transportation system36, making it challenging to guide and sustain system functions to provide transportation as a public service37.

These challenges require a shift in the role of transportation governance bodies from central authorities to coordinating institutions and consensus builders10,38,39. Public institutions must recognize the diverse interests, capabilities, and limitations of the many actors in this new ecosystem. Sharing control of the system will allow public institutions to leverage the unique capabilities of multiple actors to further the benefits of transportation while presenting challenges in terms of managing conflicting objectives and competing priorities. This will require identifying shared goals and employing a balance of regulations and incentives. Continuous evaluation and adaptation of governance approaches will be necessary as the system evolves. Public agencies will need to anticipate emergent trends and adapt to new roles in the DC regime.

Sustainability for the Anthropocene

The increase in hybridization and DC of transportation systems will require sustainability efforts to embrace the complexity and uncertainty of the Anthropocene. Legacy sustainability framings are increasingly inadequate as they do not generally recognize that: (i) control is wielded by new parties, (ii) the traditional boundaries defining transportation and interdependent systems are diffusing, and (iii) environmental complexity is producing novel dynamics that will profoundly impact transportation systems. Achieving sustainability goals will become more challenging given the increasing complexity of interconnected systems and lack of clarity in who dictates actions and approaches. These challenges require reframing the uncertainty, complexity, volatility, and ambiguity of the Anthropocene40 not as an impediment to sustainability, but as a charge to develop novel strategies that challenge normative models of how transportation systems work.

The transportation resilience field is uniquely positioned to inform system change during the Anthropocene. Broader resilience communities reflect domains that embrace disruption and challenge system rigidity and mental models underpinning system functionality. These communities recognize that successful systems innovate, adapt, and transform by responding to their changing and uncertain environments at pace and scale41,42,43. While sustainability is generally viewed through a normative lens and pursued through sets of goals, resilience is focused on change-oriented actions and rethinking system response capabilities44. For example, decision-making and assessment of carbon reductions have typically primarily considered technology manufacturers, fuels, travel behavior, and related policies. In the future, carbon reductions will be steered by additional actors and systems including routing technologies leveraging smart phone data, smart chargers controlled by power companies, and vehicle-to-grid battery energy systems to protect homes during blackouts. Achieving normative sustainability goals will be challenging in a future where the complex environment created by the CE reduces clarity in what is happening and who has control.

Recognizing the paradigm-shifting role of the CE in changing the nature of transportation systems is critical to transportation sustainability. We must consider whether the CE is an appropriate lens to understand actions, outcomes, and uncertainties, and its role in directing sustainability outcomes. For example, the adoption of eco-routing in Google Maps could have a much greater effect on sustainability than most local and regional efforts. This raises questions including how routes are determined, who benefits or is harmed, and what the implications are for public agencies who will have less control over supplying mobility. Policies should not simply target a single actor like Google, but address and incorporate the complex ecosystem of data flows, analytics, and DC. This will require new regulatory frameworks and approaches that acknowledge the influence of distributed actors and the relevance of emerging cognitive capabilities. Put simply, sustainability will be an artifact of the CE.

Sustainability efforts will take place within the diffuse boundaries of transportation and the CE and will require leveraging new control paradigms to exert change. Capabilities emerging from the CE will enable new approaches to transportation sustainability, but also present new challenges. Advanced sensors in vehicles and on people (e.g., as cellphones) will enable rapid data collection, leading to novel information flows that can be incorporated into governance strategies through iterative measurements, real-time responses, and adaptive management to achieve sustainability goals45. Likewise, greater integration of information and systems into the CE will allow actors to make decisions based on real-time information. While this could empower people to make decisions aligned with sustainability goals, it does not guarantee it.

The shift to DC will impact the ability of individuals and large entities to pursue sustainability objectives and prioritize their own needs. Automated ride-share opportunities will create new mobility options, resulting in economic benefits for users and affecting emissions46,47. Increasing AV penetration could allow for system-wide optimizations48, but will reduce passenger decision-making capacity49. Increased component-level control may increase individual agency, but also lead to more centralized power structures. For example, if all vehicles were autonomous and controlled by cloud-based routing applications, Google (or equivalent) could direct the vehicle fleet to reduce traffic congestion, minimize air pollutant emissions in marginalized communities, and avoid flooded roadways. However, they could also choose to route the fleet according to different objectives, leading to vulnerabilities.

The emergence of AI and its potential for changing cognition is a critical unknown for transportation systems. In addition to being a tool for analyzing large data streams, AI produces a suite of emerging capabilities that could influence transportation decision-making. Soon AI may be given the autonomy to participate in decision-making processes. Increasing hybridization means decision-making autonomy in single systems (e.g., cloud-based routing, EV charging) may drive transportation outcomes. These dynamics represent a new frontier for the technical and decision-making sciences supporting transportation systems. Early AI implementations could steer transportation systems towards particular outcomes. Who chooses these outcomes is important. As AI is given more autonomy and access to decision-making across hybrid systems, the sustainability implications become murky. Transportation planning will need to acknowledge the complexity of integrating AI into the CE in an uncertain environment with limited transparency and implications across systems.

Conclusion

Acknowledging a shift towards hybridization and DC is underway, transportation public agencies will need to reconsider their role in governing the transportation system. Rather than acting as purveyors of supply, they are now well positioned to act as consensus builders in an increasingly complex landscape. Agencies should recognize that even as they lose control of supply, new opportunities will emerge for guiding how transportation systems serve public interest in the Anthropocene. The increasing diversity of players will bring the need for consensus building and satisficing50. As new players and AI exert control, agencies should ensure that these new systems are steered by the communities they serve, which will likely require inclusive engagement practices and guardrails to prevent systems from being overtaken by AI. Building consensus across the multitude of players will be challenging given the range of goals and priorities, and public agencies will need to develop novel approaches to elucidating shared goals and visions for transportation systems. Cross-system interactions and cyberphysical system management should become core to the missions of transportation agencies.

Responses