Characterizing the variation in safflower seed viability under different storage conditions through lipidomic and proteomic analyses

Introduction

Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.), a member of the Asteraceae family, serves as a versatile cash crop. The dried tube flowers of safflower are utilized as Chinese medicinal materials and are known for their hot, bitter, and warm properties. In traditional Chinese medicine, they are commonly used to promote blood circulation and remove blood stasis. Historically, safflower was regarded as one of the raw materials for dye production before the advent of chemically synthesized dyes1. Safflower seeds are of both medicinal and economic value due to their high content of unsaturated fatty acids. Specifically, their Linoleic acid (LA) content is approximately 74%2. Safflower also has a rich history of use in Chinese medicine for treating cardiovascular diseases, showcasing notable anti-myocardial ischemia effects3. Additionally, safflower exhibits various pharmacological properties such as anti-coagulant, antioxidant, and neuroprotective effects4. Safflower was introduced to the mainland by Zhang Qian during the Western Han Dynasty, following his travels to the Western regions. It was further spread across the world during the Tang Dynasty, mainly through the efforts of Tang Dynasty ambassadors. Presently, safflower is extensively cultivated in China, with significant plantations in Xinjiang, Yunnan, Sichuan, and Henan provinces. Notably, Xinjiang boasts a large safflower planting area5. Despite its global cultivation, safflower remains an underutilized cash crop in terms of its potential value, adaptability to high temperatures, drought, saline-alkali lands, and the changing environmental conditions observed in recent years.

Seeds are the fundamental materials for agricultural planting and production, playing a crucial role in determining the level of agricultural output. However, seed aging presents a significant challenge to seed germination, production, and storage, resulting in considerable economic losses. It has emerged as one of the primary threats to seed vitality6.

Numerous factors contribute to seed aging, encompassing both genetic (internal) and environmental (external) factors. During the natural aging process, seeds generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), also known as free radicals. Excessive accumulation of ROS, primarily produced by mitochondria, induces abnormal cell metabolism and accelerates aging7. Seed aging involves distinctive cellular, metabolic, and chemical changes, including chromosomal aberrations, DNA damage, reduced RNA and protein synthesis, alterations in enzyme and sugar reserves, and compromised membrane integrity8;9. Our previous study demonstrated a significant decline in germination percentage of safflower seeds stored at room temperature for different durations (4 months, 16 months, and 28 months). Moreover, an increase in aging time was accompanied by a notable decrease in catalase (CAT) activity and a significant rise in malondialdehyde (MDA) content. Additionally, the aging process led to substantial modifications in both the surface and internal structure of the cotyledon. Therefore, investigating improved preservation methods for safflower seeds holds great significance.

Low temperature and air isolation have been identified as effective methods to prolong the longevity of seeds. Research has demonstrated that Dendrobium officinale seeds, when dried and stored at different temperatures including room temperature, 4 °C, -20 °C, and in liquid nitrogen, exhibit varying germination percentages. Notably, when the seed water content reaches 20.63%, the germination percentage can achieve 94.15%. Additionally, a seed moisture content ranging from 10 to 20% can result in a seed germination percentage exceeding 90%. Optimal storage practice involves subjecting the seeds to 24 h of drying treatment followed by storage in liquid nitrogen10. Furthermore, an investigation was conducted on the impact of different packaging methods on the storage stability of 89 wheat seeds in foil bags and non-vacuum aluminum boxes at -40℃ over an 11-year period in a low-temperature germplasm bank. This article examines storage effects under low-temperature conditions by analyzing three aspects: the difference in germination percentage between stored seeds and the initial germination percentage before storage, the difference in seed germination percentage between the two packaging methods across different years, and the difference in seed germination percentage between the two methods within the same year. The findings indicate that, after 11 years of low-temperature storage, 82% of the material exhibited an average germination percentage higher than the initial rate. However, a significant decrease in germination percentage was observed only after the 10th year of storage in comparison to the initial germination percentage. Additionally, the germination percentage decline in seeds stored in aluminum foil bag packaging was less pronounced than in those stored in aluminum boxes, with a statistically significant difference. Moreover, the storage effect of vacuum-sealed aluminum foil bag packaging was significantly superior to non-vacuum packaging11. Nonetheless, further research is required to explore the specific mechanisms underlying the situation in safflower.

To investigate the effects of temperature and oxygen levels on the membrane structure of safflower seeds, an array of storage conditions were employed, including: -18 °C, vacuum -18 °C, -4 °C, vacuum -4 °C, 4 °C, vacuum 4 °C, 15 °C, vacuum 15 °C, 25 °C, and vacuum 25 °C. The seeds were subjected to these conditions for a duration of one year. Initially, X-ray imaging technology was utilized to assess seed fullness and germination percentages. Subsequently, TTC staining and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were employed to examine seed viability and cotyledon outer surface cell structures. Concurrently, catalase (CAT) activity and malondialdehyde (MDA) content analyses were conducted, accompanied by the determination of proteomic and lipidomic profiles of safflower seeds following one year of storage in varying environments. Additionally, the presence of differentially expressed proteins and lipid metabolite variations were scrutinized. Ultimately, the specific influence of temperature and vacuum on seed aging was analyzed. The objective of this study is to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying natural aging in safflower seeds under diverse environmental conditions and establish a scientific foundation for their preservation.

Materials and methods

Experimental material

Safflower were planted in the Medicinal Plant Garden of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and all the safflower seeds used in the experiment were collected by ourselves. The seeds were kept in a clean kraft paper bag, then the part was removed and vacuumed, placed in sealed bags. The air was extracted with a vacuum machine (Starfish family, ZK-8815). Subsequently, they were stored together with untreated seeds at -18 °C, -4 °C, 4 °C, 15 °C, and 25 °C. After one year, 20 seeds were chosen from each seed bag kept under different conditions for X-ray examination and germination rate determination.

X-ray imaging

The experiment utilized the MX-20 Cabinet X-ray System (Faxitron, AZ, USA). X-ray technology is an efficient tool for examining the interior aspects of seed embryos, endosperms, and detecting mechanical damages, fractures, and presence of pests, while ensuring minimal seed damage12,13. Such analysis provides essential insights for determining seed viability, germination percentage, health status, and degree of fullness among others. Imaging was facilitated by a 12 cm x 12 cm DC-12 camera, which captured images of the seeds. The camera’s 20 μm nominal focal spot and up to 5 times geometric magnification yielded images with ultra-high contrast and high spatial resolution. Approximately twenty seeds were included in each image capture.

Determination of water content

Seeds from an extensive variety of plant species conclude their developmental phase by shedding a significant portion of their cellular water content, achieving a state of anhydrobiosis. In this state, cellular functions and metabolic activities are halted, and the cellular contents are solidified. This desiccated state endows seeds with the remarkable ability to transcend time and space, a critical attribute for species dissemination and foundational for global agriculture and food security. It preserves the seeds’ inherent value, ensuring their viability for subsequent planting seasons14. Put the clean aluminum tray into the oven for 2 h, weigh and record it as M0, then put 10 g seeds which were stored for 1 year under different conditions into a clean aluminum tray, weigh and record it as M1, put the aluminum disc and seeds into a constant temperature oven at 103 ± 2 °C for 8 h, then weigh and record it as M2. The experiment was repeated 5 times. The seed moisture content (%) = (M1-M2)/(M1-M0) × 100%.

Germination percentage determination

Twenty seeds were randomly selected from ten sample sets that underwent natural aging for one year at different storage environments and temperatures. A sodium hypochlorite (NaClO3) solution with a concentration of 1.66% was prepared, resulting in a total volume of 140 ml. Subsequently, the seeds are immersed in NaClO3 solution, rinsed under running water for approximately three minutes, and then blotted with a paper towel. The seeds are then placed on Petri dishes with 1% agar. Observe and record germination percentages one day later, observation for 7 days. The experiment was repeated five times to ensure accuracy and reproducibility of the results.

Staining of 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazole chloride (TTC)

Five safflower seed samples were isolated from each group asnd placed into cryogenic storage tubes, following which an adequate amount of distilled water was added. After a period of six hours, the samples were removed, de-shelled, and positioned on a Petri dish. Subsequently, a 1% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining solution was prepared and introduced into the Petri dish, avoiding the seeds. The Petri dish was then sealed and subjected to a water bath regulated at 37 °C.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

Following one year of preservation, the cellular structure of the outer surface of safflower seed cotyledons was examined utilizing scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Cotyledon outer surfaces were meticulously dissected using a scalpel and subsequently affixed onto an aluminum stub using double-sided adhesive tape. Following gold sputter coating, variations in cell structure were observed under an acceleration voltage of 6.00 kV.

Activity of catalase (CAT)

The spectrophotometer was activated and preheated for a minimum of thirty minutes, its wavelength adjusted to 240 nm, and its baseline set using distilled water. Subsequently, 0.1 g of seed kernel was collected into an Eppendorf (EP) tube, to which 1 ml of catalase (CAT) extract and a steel bead were added. This mixture was homogenised then subjected to centrifugation (8000 g, 4 °C, 10 min) for 30 s. The reagent solution for CAT detection was immersed in a water bath regulated at 25 °C for ten minutes. A quantity of 10μL of sample supernatant and 190μL of reagent solution was introduced into the cuvette, promptly mixed and timed. The initial absorption value (A1) at 240 nm and the absorption value (A2) after one minute were recorded, with the difference (ΔA) calculated as A1—A2. The experiment was repeated five times.

Content of malondialdehyde (MDA)

The microplate reader was switched on and preheated for a duration of at least 30 min; the respective absorbance settings were established at 532 nm and 600 nm, with distilled water serving as the zero reference. Following this, 0.1 g of seed kernels were acquired and placed into Eppendorf (EP) tubes, to which 1 ml of malondialdehyde (MDA) extract and steel balls were included. The mixture was subjected to a homogenizer and then centrifuged (8000 g, 4 °C, 10 min) for 30 s. Assay tube reagents (consisting of 100μL supernatant, 300μL MDA working solution, 100μL Reagent III) and blank tube reagents (consisting of 100μL distilled water, 300μL MDA working solution, and 100μL Reagent III) were prepared accordingly. The assay tube was then positioned in a water bath held at 100 °C, later to be transferred to an ice bath for one hour for rapid cooling. Following centrifugation (10000 g, room temperature, 10 min), 200μL of each supernatant was transferred into a 96-well plate to determine the sample’s absorbance. From these readings, the respective Δ532 and Δ600 values were calculated. The experiment was repeated five times.

Lipidomics data analysis

In this study, four experimental conditions were selected, namely -18 °C, 25 °C, vacuum -18 °C, and vacuum 25 °C, and were assigned the labels L1, L2, L3, and L4, respectively. Using the CD search library software for simple screening and peak alignment of raw data, peak extraction and quantification are performed based on parameters such as retention time deviation, mass deviation, signal intensity deviation, signal-to-noise ratio, and minimum signal intensity; predicting molecular formulas through molecular ion peaks and fragment ions, and comparing them with the Lipidmaps and Lipidblast databases; removing background ions with blank samples and normalizing the quantification results. Subsequently, multivariate statistical analysis is conducted using the metaX software, including Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), to determine the VIP values of metabolites. Univariate analysis calculates the P-values and fold changes of metabolites based on t-tests, with the criteria for screening differential metabolites being VIP > 1, P-value < 0.05, and FC ≥ 2 or FC ≤ 0.5. Finally, the R package ggplot2 is used to draw volcano plots, Pheatmap for clustering heat maps, and the corrplot software package for drawing correlation graphs between differential metabolites.

Proteomics data analysis

Seeds stored at -18 °C, 25 °C, vacuum -18 °C, and vacuum 25 °C for one year were selected as lipid sequencing samples and labeled as P1, P2, P3, and P4 respectively. Proteomic sequencing was performed by the commissioned service of Beijing Nuohe Zhiyuan Technology Co., Ltd. The mass spectrometry data is analyzed using the Proteome Discoverer software for database searching, with a precursor ion mass tolerance set to 10 ppm and a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.02 Da, considering both fixed and variable modifications, and allowing for up to 2 missed cleavage sites. The analysis results are filtered to retain only peptides with a confidence level above 99% and proteins containing at least one unique peptide, with a false discovery rate (FDR) validation to remove peptides and proteins with an FDR greater than 1%. Statistical analysis of the protein quantification results is performed using a T-test, defining proteins with p < 0.05 and |log2FC|> * as differentially expressed proteins (DEPs). Further functional annotation is conducted using the interproscan software for GO and IPR, as well as COG and KEGG pathway analysis15;16. DEPs are subjected to volcano plot, cluster heat map analysis, and pathway enrichment analysis, with the STRING DB software used to predict protein–protein interaction networks.

Result

Analysis of the activity and structure of safflower seeds after one year of storage under different storage conditions

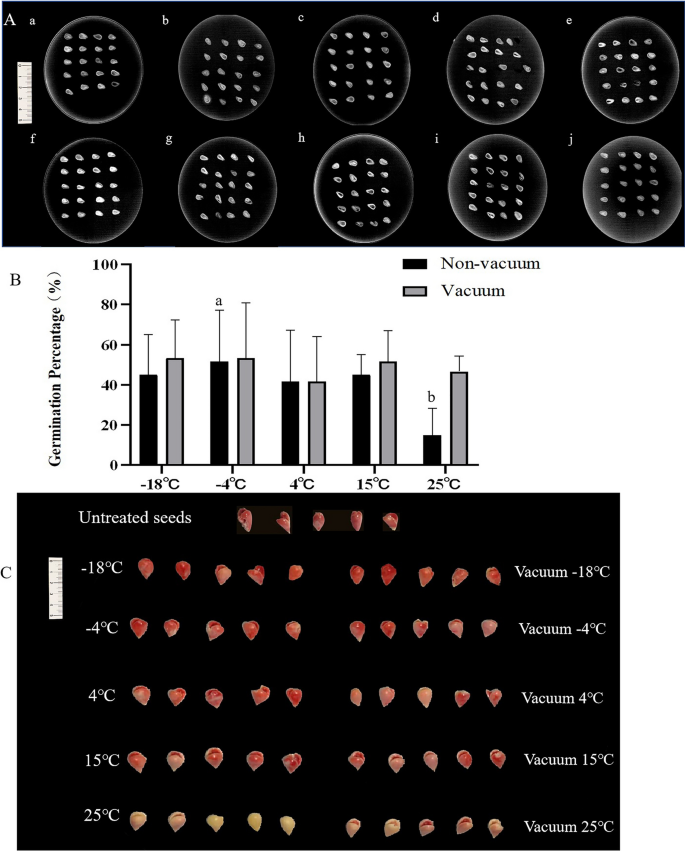

To investigate the relationship between the vitality of safflower seeds and different treatments, as well storage environments, we stored safflower seeds for one year under various conditions: -18 °C, vacuum -18 °C, -4 °C, vacuum -4 °C, 4 °C, vacuum 4 °C, 15 °C, vacuum 15 °C, 25 °C, and vacuum 25 °C. We measured their moisture content and germination percentage. To ensure the accuracy of the results, we first used X-ray imaging technology to observe the internal structure of the seeds to check for integrity. The results showed no significant difference in the degree of fullness within the seeds (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, the water content was tested, we found that the water content of the untreated seeds was around 7% overall, the lowest moisture content of the seeds stored at -18 °C was 7.95% among the treated seeds, and the highest was stored at 25 °C at 10.74%. Table S1 provides detailed data. Finally, we determined the germination rate of safflower seeds stored for one year under different conditions. The results revealed that seeds treated with vacuum and stored at -18 °C exhibited the highest germination percentage at 53%, whereas those naturally aged at 25 °C had the lowest germination percentage at only 15% (Fig. 1B). Detailed results are presented in Table S2. Additionally, the experiment also found that safflower seeds treated with vacuum generally had lower moisture content and slightly higher germination percentages compared to untreated seeds.

Differences in integrity and activity of seeds after preservation for one year in different environments. (A) Seed integrity was analysed using X-ray imaging techniques. a, seeds stored at -18℃ for one year; b, seeds stored in vacuum -18℃ for one year; c, seeds stored at -4℃ for one year; d, seeds stored in vacuum at -4℃ for one year;e, seeds stored at 4℃ for one year; f, seeds stored for one year in vacuum at 4℃; g, seeds stored at 15℃ for one year; h, seeds stored for one year under vacuum at 15℃; i, seeds stored at 25℃ for one year; j, seeds stored for one year at a vacuum of 25℃. (B) Seed germination percentage. (C) TTC staining results. Different lowercase letters in the histogram indicate significant differences between different storage conditions (P < 0.05).

To delve deeper into seed viability under varied storage environments, triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining was utilized. The outcomes elucidated a significantly enhanced viability of seeds subjected to a one-year ageing process at -18℃, when juxtaposed with seeds aged at 25℃ for an equivalent period. Moreover, the staining outcomes at 25℃ demonstrated that vacuum preservation markedly influenced seed viability. Remarkably, safflower seeds conserved under vacuum conditions manifested considerably elevated vitality in contrast to their non-vacuum preserved counterparts, as visually represented in Fig. 1C.

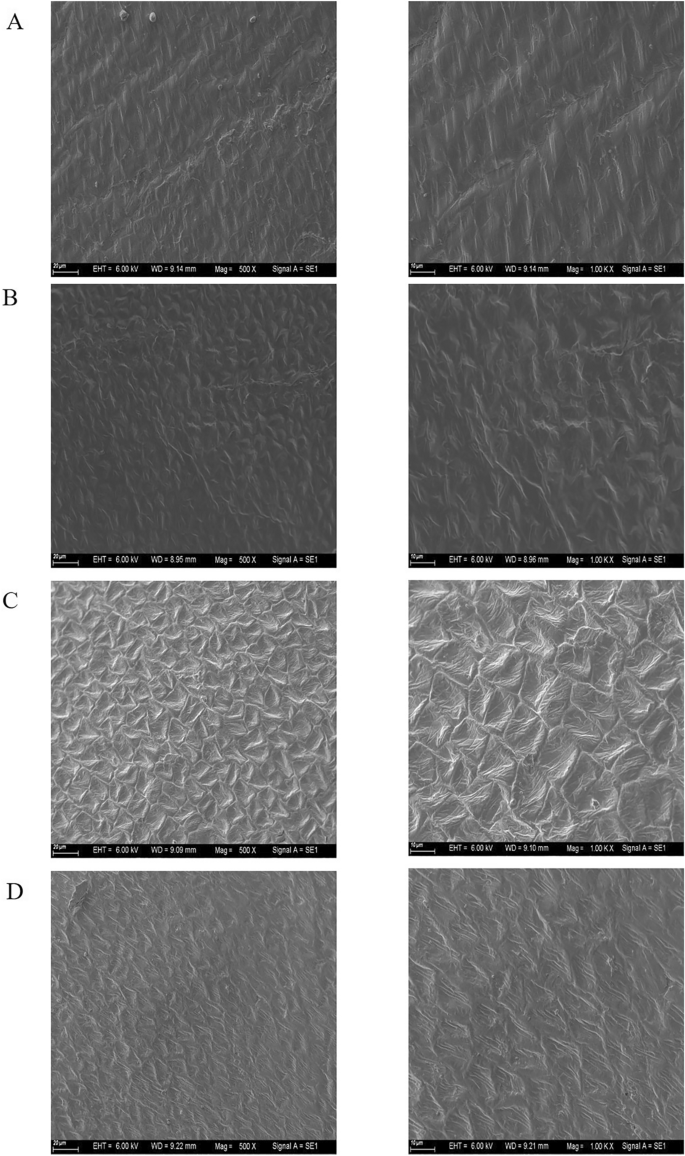

Significant differences in seed viability can be viewed after the safflower seeds have undergone an aging process at -18 °C and 25 °C over the course of one year. To conduct an exhaustive exploration of seed alterations post one-year preservation across varying environmental conditions, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was employed to scrutinize the external surface morphology of the safflower seed cotyledon. Preservation at -18℃ seemingly conserved an unblemished cotyledon structure, with a scarcely discernible intercellular space (Fig. 2A). Moreover, vacuum preservation manifested an even more impeccable structural integrity (Fig. 2B). Conversely, seeds subjected to non-vacuum storage at 25℃ over a year exhibited significant cotyledon surface corrugation and conspicuous intercellular spacing (Fig. 2C). However, vacuum preservation somewhat attenuated this predicament, diminishing the intercellular space within the seed cotyledon (Fig. 2D). On the whole, the surface morphology of safflower seeds aged over a year under subzero temperatures in conjunction with vacuum preservation exhibited considerable structural preservation. Conversely, the cotyledon structure of seeds conserved at 25℃ without vacuum treatment incurred significant damage observable through disrupted cell spaces and potential annihilation of the seed cell membrane.

External surface structure of safflower cotyledon preserved in different environments for one year. (A) Seeds stored at -18° C for one year. (B) Seeds stored in a vacuum of -18° C for one year. (C) Seeds stored at 25 ℃for one year. (D) Seeds stored at a vacuum of 25° C for one year. On the left is an image magnified 500x. On the right is an image that is magnified 1000x.

Physiological and biochemical changes of safflower seeds after one year of storage under different storage conditions

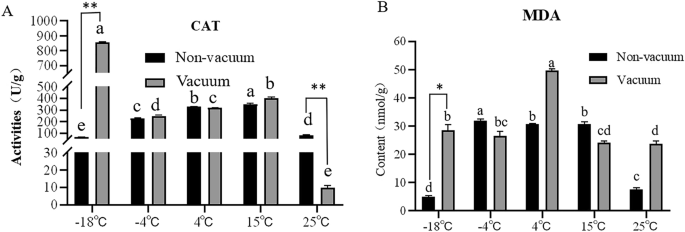

Catalase (CAT) is ubiquitously present in plant tissues, acting as a pivotal protective enzyme whose role encompasses efficacious eradication of hydrogen peroxide generated during cellular metabolic processes, thus thwarting detrimental effects of excessive peroxide on cellular health17. Malondialdehyde (MDA), the terminal result of unsaturated fatty acid oxidation in seeds, can inflict profound damage on the seed membrane system18;19), serving as a reflection of the degree of membrane lipid peroxidation and membrane system structural integrity20. Therefore, we evaluated CAT activity and MDA content in safflower seeds following a one-year preservation period under varying storage conditions. Our results illustrated that, in the absence of vacuum, the CAT activity exhibited thermosensitivity with an overall trend of initial surge followed by a subsequent reduction. While seeds preserved at lower temperatures illustrated diminished CAT activity, a progressive incline trailed by a decline was noted with augmenting temperatures. Conversely, under vacuum storage, seeds conserved at lower temperatures demonstrated consistently high CAT activity. Interestingly, aside from 25℃, CAT activity of seeds preserved at all other temperatures under vacuum exceeded that under nonvacuum storage conditions (Fig. 3A and Table 1).

Physiological and biochemical changes of seeds stored in different environments for one year. (A) CAT activity. (B) MDA content. Different lowercase letters in the histogram indicate significant differences between different storage conditions (P < 0.05). **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

The assessment of MDA content unveiled a discernible discrepancy in the MDA levels of seeds preserved under disparate conditions. Notably, seeds conserved at -18℃ in a non-vacuum setting displayed substantially reduced MDA concentrations in comparison to those maintained at -4℃ or higher temperatures. In a contrasting manner, a insight was gleaned as we discerned that the MDA content in the majority of safflower seeds subjected to vacuum preservation for one year surpassed the levels observed in seeds conserved without vacuum (Fig. 3B and Table 2).

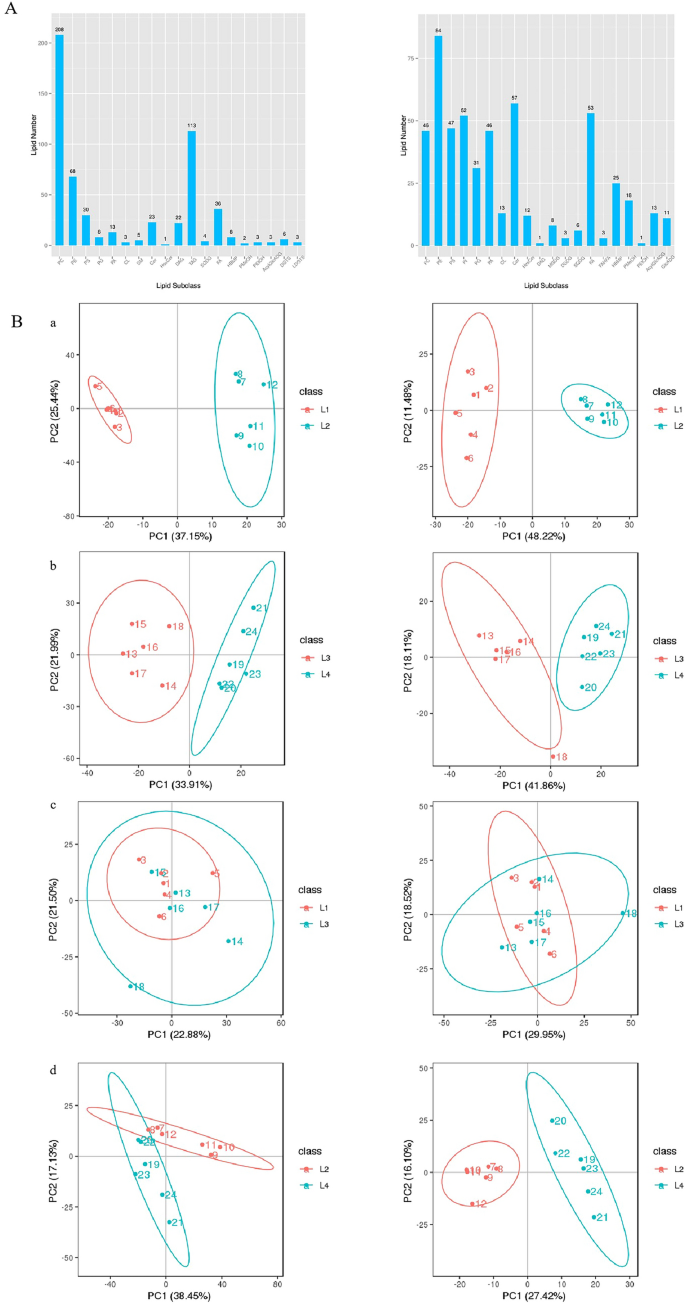

Lipidomic analysis of safflower seeds after one year of storage under different storage conditions

Safflower seeds, characterized by their high oil content, exhibited significant variations in seed viability under different storage conditions, particularly at -18 °C and 25 °C. We aimed to conduct an exhaustive analysis of the lipid profile at these temperatures. Lipidomic analysis was performed utilizing the high throughput Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS) technique. We identified a total of 1148 lipid compounds in positive ion mode and 863 compounds in negative ion mode, distributed across all 24 samples, thereby giving rise to 24 distinct species. Remarkably, triacylglycerol (TAG; 113 species subclass), phosphatidylcholine (PC, 254 species), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE, 152 species), and fatty acids (FA, 89 species) featured high abundance, primarily in the positive ionization mode (Fig. 4A, Tables S3 and S4). A differential analysis was subsequently conducted, and the outcomes of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) delineated substantial variations between L1VL2 constituents, facilitating their clear segregation into independent clusters. Moreover, intra-cluster aggregation instances were high. Additionally, a clear distinction could be observed between L3VL4 and L2VL4 clusters. Despite partial overlaps, these two clusters could still be effectively differentiated. Such discernible separations were perceivable for both positive and negative ion modes. Nonetheless, the difference between L1VL3 was marginal, with a high degree of overlap and insufficient differentiation observed (Fig. 4B).

Seed lipid and PCA analysis. (A) Seed liposome analysis. (B) PCA analysis diagram. L1 indicates that the seeds have been stored at -18 °C for one year, L2 indicates that the seeds have been stored at 25 °C for one year, L3 indicates that the seeds have been stored at -18 °C for one year, and L4 indicates that the seeds have been stored at 25 °C in a vacuum for one year. The left side is in positive mode. The right side is in negative mode.

Differential lipid compounds were analyzed to compare the lipidomic profiles of safflower seeds under various storage conditions, including positive ion mode (Fig. S1A) and negative ion mode (Fig. S1B). Venn diagrams highlighted significant differences in lipid composition, particularly between seeds stored at -18 °C and 25 °C, with vacuum storage at -18 °C further influencing lipid metabolites. Cluster analysis was performed to explore lipid metabolic patterns, revealing that lipid compounds with similar profiles may share functions or pathways. Hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) of normalized data (Fig. S2) demonstrated distinct lipid expression patterns under different storage conditions in both positive (A) and negative ion modes (B). The heatmap showed upregulation (red), downregulation (blue), or no change (white/light) in lipid abundance. Significant differences in expression patterns were observed among storage conditions, with certain metabolites notably upregulated or downregulated in specific groups (L1–L4). These variations reflect the impact of storage conditions on lipid metabolism and indicate distinct biological functions or regulatory mechanisms. Both ion modes revealed substantial shifts in lipid abundance, emphasizing the complexity of lipid metabolism under different storage environments, particularly at low temperatures and vacuum conditions.

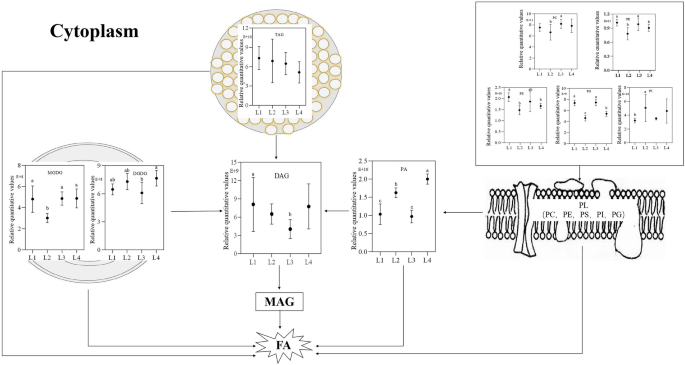

These findings align with previous results obtained through TTC staining, which revealed a significant difference in seed vitality after one year of storage at -18 °C and 25 °C. However, vacuum storage at -18 °C showed no substantial variation in seed vitality. In both L1VL3 and L2VL4 clusters, the triacylglycerols (TAGs) exhibited a decline during natural seed aging. The L1VL3 cluster showed a significant reduction in all four TAGs, while the L2VL4 cluster displayed a substantial decrease in 18 out of 19 TAGs. Within the L1VL3 cluster, all three phosphatidic acid (PA) species experienced a sharp decrease, whereas within the L2VL4 cluster, only a third of the TAG species displayed a significant reduction (Table 3). The lipid content of specific membrane lipids, including phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and PA, as well as storage lipids such as TAG and diacylglycerol (DAG), showed considerable variability. There were divergent trends observed in PA content under different conditions: non-vacuum storage at -18℃ resulted in reduced PA content, whereas a significant increase was observed following storage at 25℃. This underscores the substantial impact of temperature on the evolution of PA content, as higher temperatures amplify PA levels. Additionally, subsequent examinations revealed that the content of PC, PE, phosphatidylserine (PS), and phosphatidylglycerol (PG) species increased after one year of storage at -18℃, whereas they significantly decreased after a year-long storage at 25℃ (Fig. 5).

Analysis of lipids of seeds stored in different environments for one year. Membrane lipid (PL) is first degraded to phosphatidic acid (PA), then degraded to diacylglycerol (DAG), triacylglycerol (TAG), monogalactodiyl glycerol (MGDG), and digalactodiglycerol (DGDG) directly degraded to DAG. DAG is then degraded to monoacylglycerol (MAG) and finally to fatty acids (FA). L1, Store at -18 °C; L2, Store at 25 °C; L3, Store under vacuum -18 °C; L4, Store under vacuum 25 °C. Different lowercase letters in the histogram indicate significant differences between different storage conditions (P < 0.05).

Proteomic analysis of safflower seeds after one year of storage under different storage conditions

We utilized TMT-based quantitative proteomics, successfully identifying 5004 proteins across 12 samples, of which 4991 proteins were quantified within a 95% confidence interval (Table S5). The differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were divided into four subgroups (P1/P2, P3/P4, P1/P3, P2/P4) and subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) and clustering analysis. However, as shown in Fig. S3 and Fig. S4, no significant differences were observed between groups, and the within-group cohesion was poor. A total of 274 significantly differentially expressed proteins were identified between the four groups (fold change ≥ 1.2 or ≤ 0.83, P < 0.05) (Table S6).

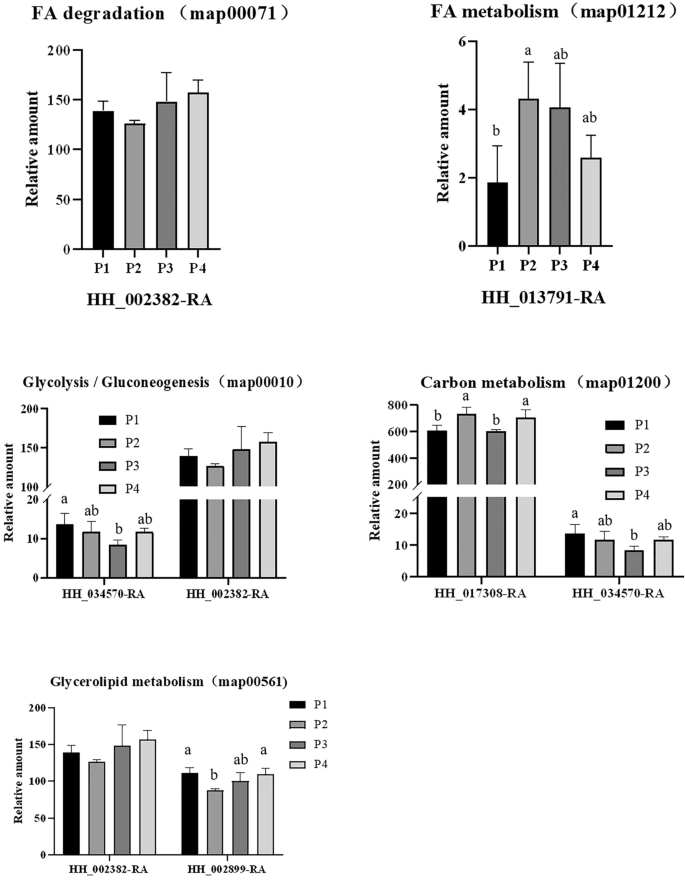

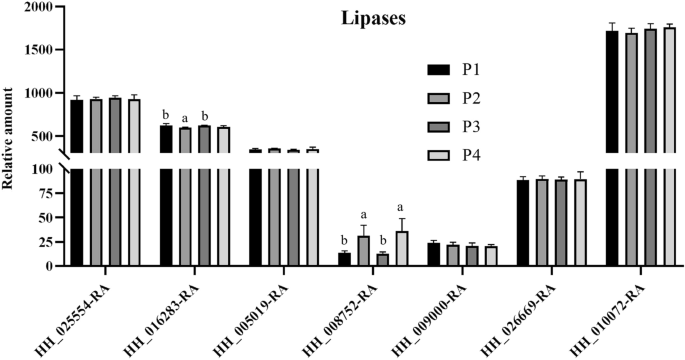

During safflower seed storage, respiration progressively consume soluble sugars and eventually lead to seed deterioration21;22. In addition, a reduction in structural lipids, such as phospholipids and galactoselipids, can lead to a loss of seed viability23. We focused on investigating the metabolic pathways related to sugar and lipid metabolism. These pathways include starch and sucrose metabolism (map00500), carbon metabolism (map01200), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (map00010), fatty acid metabolism (map01212), glycerolipid metabolism (map00561), fatty acid degradation (map00071), glycosphingolipid biosynthesis – globo and isoglobo series (map00603) and sphingolipid metabolism (map00600). KEGG analysis identified 35 DEPs in group P1/P2, 21 in P3/P4, 21 in P1/P3, and 27 in P2/P4 (Table S7-S10). Table 4 summarizes the total DEPs, along with up- and down-regulated proteins. Most DEPs were localized to five key pathways: glycerolipid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, carbon metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and fatty acid degradation, though intergroup variation was minimal. Five specific gene-encoded proteins (HH-002899-RA, HH-002382-RA, HH-034570-RA, HH-013791-RA, HH-017308-RA) showed differential abundance (Fig. 6). Notably, HH-013791-RA and HH-017308-RA exhibited increased expression with rising storage temperatures under non-vacuum conditions. Conversely, HH-002899-RA, HH-002382-RA, and HH-034570-RA displayed higher expression levels after one year of low-temperature storage (-18 °C) compared to high-temperature storage (25 °C), indicating that lipase genes are involved in lipid degradation. Statistical analysis of lipase-coding protein abundance (HH-0087250-RA) revealed its expression level was significantly lower at -18 °C compared to 25 °C after one year (Fig. 7). These findings highlight that low-temperature storage effectively mitigates membrane lipid degradation during seed aging.

Protein detected by various metabolic pathways. (A) FA degradation (map00071). (B) Glycolysis Gluconeogenesis (map00010). (C) FA metabolism (map01212). (D) Carbon metabolism (map01200). (E) Glycerolipid metabolism (map00561). P1, Store at—18 °C; P2, Store at 25 °C; P3, Store under vacuum -18 °C; P4, Store under vacuum 25 °C. Different lowercase letters in the histogram indicate significant differences between different storage conditions (P < 0.05).

The expression level of HH-0087250-RA after storage at low temperature (-18 °C) for 1 year was significantly lower than that after 1 year of storage at 25 °C. P1, Store at -18 °C; P2, Store at 25 °C; P3, Store under vacuum -18 °C; P4, Store under vacuum 25 °C. Different lowercase letters in the histogram indicate significant differences between different storage conditions (P < 0.05).

Integration of lipidomic and proteomic data revealed significant differences in lipid profiles across storage conditions, while proteomic differences were less pronounced.Two plausible hypotheses were taken into consideration. Firstly, alternative modifying factors may have impacted enzyme activity, leading to insignificant differences in protein expression. However, the preceding activity experiment illustrated the evident influence of the preservation environment on enzyme activity. Secondly, there could be fragmented genome annotations, resulting in incomplete identification of several enzymes engaged in safflower lipid degradation. Additional investigations are necessary to investigate these specific factors.

Discuss

Seed aging is a complex process influenced by various factors, primarily involving genetic factors (internal causes) and environmental factors (external causes). Our previous experimental results showed that with the extension of the aging period, catalase (CAT) activity significantly decreased, while malondialdehyde (MDA) content significantly increased. The aging process caused significant changes in both the external and internal structures of the cotyledons. Over time, the external structure of the cotyledons gradually deteriorated from its original plump state, and the oil bodies within the cotyledons transitioned from a compact to a more relaxed state. Additionally, the total content of diacylglycerol (DAG) and phosphatidic acid (PA) increased with aging, while the content of triacylglycerol (TAG) and phospholipids (such as phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and phosphatidylglycerol (PG)) significantly decreased. Studies have shown that the levels of PA, PC, PE, PI, and PS significantly decrease during seed aging, while the level of PG increases24. This suggests that the phospholipid metabolism changes related to seed aging may vary depending on the specific crop species and handling conditions. These changes reveal that during the natural aging process of safflower seeds, the cell membrane undergoes degradation, leading to significant changes in physiological indicators and a decline in seed vitality, which is also reflected in the changes in the proteome and lipid composition25,26. We hypothesize that during seed aging, enzymatic metabolism induces structural changes in the cell membrane, leading to the influx of reactive oxygen species (ROS) into the cells, which ultimately reduces safflower seed vitality. To determine the optimal preservation method for safflower seeds, we treated them under different temperature and sealing conditions and evaluated their vitality, structure, physiology, biochemistry, lipid composition, and proteome changes after one year under different environmental conditions.

When the CAT (catalase) activity of safflower seeds stored in different environments for one year was measured, it was observed that the overall trend of CAT activity in seeds stored under non-vacuum conditions exhibited an initial increase followed by a decrease. This phenomenon can potentially be attributed to the activation of other enzymes present in the seeds that facilitate the dismutation of O2– into H2O2. The presence of increased H2O2 subsequently enhanced the CAT activity, which aids in the elimination of excess H2O227. As the H2O2 content decreased, the CAT activity gradually declined. Additionally, SOD (superoxide dismutase) was found to participate in the generation of H2O228. Our subsequent experiment aims to further evaluate the variations in SOD activity in seeds following preservation under different conditions. MDA (malondialdehyde) content is an important indicator of seed aging, and lower MDA content means lower membrane damage. Conversely, greater membrane damage results in higher MDA content29. For example, the MDA content of pine seeds increases dramatically after 25 days of accelerated aging at 45 °C and increases to 21-fold after 35 days of control30. In this paper, the effects of accelerated aging on MDA content in wheat seeds, and the effects of storage temperature and vacuum storage on MDA accumulation in safflower seeds were introduced. The results suggest that the accumulation of MDA during aging may vary depending on the plant species and the preservation environment, and further research is needed to determine whether lipid composition assays can better assess lipid peroxidation in seeds31. The studies cited in the article suggest that the accumulation of MDA does not necessarily exacerbate membrane lipid peroxidation in seeds with extended storage time, and that the accumulation of MDA during aging may be species-related.

By integrating lipidomics and proteomics analysis results, significant differences were observed between the lipid groups and the proteome in different preservation environments, while the disparities within the proteome were relatively inconspicuous. We considered the following four possibilities: First, low temperature and vacuum treatment slow down seed metabolic activity: low temperature and vacuum treatment can significantly slow down seed respiration and metabolic activity, thus delaying the natural aging process32;33. Although this treatment extends the storage period of seeds, it does not completely stop the aging process. Seeds stored under low temperature and vacuum conditions still undergo gradual physiological and structural changes, so the differences in proteomics might be relatively small and not easily distinguishable from naturally stored seeds. Second, the stability of proteins: Some proteins in seeds, such as storage proteins and structural proteins, have strong stability and are less likely to degrade under low temperature and vacuum conditions. Since low temperature and vacuum reduce oxidative reactions and moisture influences, these proteins remain stable, meaning that changes in the proteome under these conditions may not be as significant as those observed in naturally stored seeds34. Third, the gradual occurrence of the aging process: low temperature and vacuum treatment slow down metabolism, but they do not completely stop the aging process in seeds, particularly in terms of protein degradation and synthesis. This means that although the aging process is slower under these conditions, some subtle physiological changes will still occur over time, and these changes might not manifest as significant proteomic differences in the short term25. Fourth, experimental conditions and detection sensitivity: In proteomic analysis, some minor changes might not be detected, especially when the preservation method effectively slows down the aging process. These subtle changes may not be significant enough in terms of protein expression or function to show noticeable differences in proteomic data35. Lipases play a crucial role in the natural aging process36, and earlier studies have found that two specific lipases (HH-026818-RA and HH-025320-RA) increase in expression during seed storage26Moreover, lipases are also involved in glucose metabolism and fatty acid degradation, leading to the breakdown of oil bodies (triacylglycerols—TAG) and membrane lipids (PC, PE, PS, PI, PG). These processes result in the disruption of seed structure and a decline in seed vitality during natural aging. It can be speculated that during seed storage, the oxidation of seeds gradually increases with the extension of storage time, which may be related to lipid degradation. Lipid degradation leads to changes in both membrane structure and oil body structure, making it easier for ROS to penetrate the seeds. However, in the current experiment, it was observed that seeds stored under low-temperature vacuum conditions had a tighter surface structure compared to those stored under high-temperature non-vacuum conditions, with no collapse or cracking. This phenomenon may be due to the different seed treatment conditions used in this study compared to previous experiments. Specifically, low temperature and vacuum treatment were found to reduce seed respiration and effectively inhibit seed metabolism37;38

Our study revealed that the differences observed between the groups were consistent with the outcomes of previous experiments based on lipid analysis. Furthermore, we observed that the contents of PC, PE, PS, and PG were highest when stored at low temperature (-18℃), and gradually decreased with an increase in storage temperature. However, the contents of PA and PI showed an opposite trend, increasing with an increase in temperature, while the change in contents after vacuum storage was not significant. These observations suggest that changes in membrane lipid metabolism during seed aging vary by crop species and treatment conditions. We hypothesize that enzymes related to fat degradation are involved in the aging process under different preservation conditions, leading to the deterioration of membrane lipid degradation and impaired activity. During proteomic analysis, only five metabolic pathways were detected, and the five gene-coding proteins selected from them had not been identified in previous experiments. We speculate that the differences may be attributed to the selection of experimental materials. In the previous experiment, we used seeds that grew at different times of natural aging, while in this experiment, we used seeds that had been stored in different environments for one year. The different treatment methods of experimental materials may have led to differences in the proteome.

In the forthcoming research, we will persistently investigate the detectability of a specific protein gene under distinct environmental conditions, following a one-year preservation period. Additionally, we will persist in scrutinizing the impact of the environment on the lipid composition and proteomic profile of seeds while concurrently striving to minimize preservation duration through deliberate artificial aging procedures. Expounding the identification of genes associated with seed aging, we will undertake a comprehensive exploration of the precise mechanisms underlying seed aging. Ultimately, the outcomes of this study present a novel theoretical framework for the scientific preservation of safflower seeds.

Our research findings highlight the pivotal role of low-temperature storage in enhancing the viability of safflower seeds, recommending that seed practitioners should preserve seeds in an environment close to or below the freezing point. This not only helps to slow down the aging process but also effectively extends the seeds’ lifespan. Additionally, vacuum packaging technology has shown significant effectiveness in improving seed preservation quality by reducing moisture content and minimizing oxidation reactions, thereby extending the storage duration of seeds. To ensure seed quality, regular measurements of CAT and MDA levels are essential, aiding in monitoring the physiological status of the seeds and allowing for timely interventions when necessary. Control of humidity and temperature in the seed storage environment is equally important, with a recommendation to utilize storage facilities that maintain a constant temperature and humidity, along with regular checks to ensure optimal storage conditions. Implementing a seed rotation system is also an effective strategy to maintain the optimal vitality of seeds in storage, updating stock periodically to prevent a decline in vigor that could result from prolonged storage. Education and training are crucial for enhancing the understanding of seed storage personnel regarding the mechanisms of aging and storage techniques, ensuring they can properly execute and manage seed storage. Lastly, it is encouraged that seed storage practitioners stay informed and adopt the latest advancements in seed science, leveraging new technologies and methodologies to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of seed storage. Through these comprehensive measures, there can be a marked improvement in the storage outcomes for safflower seeds, ensuring they exhibit high vitality and germination rates when applied in agricultural and medicinal contexts.

Responses