Chemogenetic induction of CA1 hyperexcitability triggers indistinguishable autistic traits in asymptomatic mice differing in Ambra1 expression and sex

Introduction

Autism spectrum Disorders (ASD) are neurodevelopmental disorders characterized on the behavioural level by sensory and attentional deficits, motor stereotypies, and decreased sociability [1, 2]. These alterations have been shown to associate with impairments in GABAergic or glutamatergic neurotransmission which alter the excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance and trigger hyperexcitability [3, 4] in cortical [5, 6], hippocampal [7, 8] and cerebellar [9] networks. Interestingly, rectification of E/I unbalance produced by increasing activity in inhibitory parvalbumin interneurons (PV-IN), or diminishing it in pyramidal neurons (PN), rescues autistic behaviors in mice with mutations in ASD relevant genes [10,11,12,13].

Among these genes, Ambra1, which encodes for Activating Molecule in Beclin1-regulated Autophagy [14], is currently gaining an increased attention due to evidence which show that Ambra1 heterozygous deletion in mice triggers autistic-like traits in a sexual dimorphic manner [15, 16]. Specifically, in mice, Ambra1 exhibits constitutively higher expression under physiological conditions, and its reduction due to Ambra1 haploinsufficiency is proportionally greater in the female hippocampus compared to the male [17]. Indeed, Ambra1+/− females exhibit social and attentional impairments, loss of hippocampal parvalbumin–positive inhibitory interneurons (PV-IN), reduced inhibitory currents onto CA1 PNs (PN) and prevalence of abundant and immature dendritic spines on CA1 PN dendrites while Ambra1+/− males are insensitive to the mutation [17]. Supporting the involvement of decreased hippocampal inhibitory tone in the ASD phenotype of Ambra1+/− females, chemogenetic increase of hippocampal PV-IN activity entirely rescues ASD-like neural and behavioral dysfunctions [18].

Aside to genetic components, the causal role of environmental factors in autism etiology has extensively been demonstrated [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. In general, ASD symptoms are driven by events altering neurodevelopment (see 19 for a review) which, in most cases, trigger brain hyperexcitability [8, 20, 21]. Some of those events have a clear parental origin like maternal infectious diseases [22], age of biological parents [23] or addictions [24]. However, external events including adverse conditions at birth [25], perinatal exposure to toxins [26], and early experience of stressful or traumatic events [27, 28] also contribute. Although addictive effects of genetic and environmental ASD factors have been pointed out [29, 30], an aspect not yet investigated relates to the latent ASD risks of asymptomatic mice which bear susceptibility factors insufficient to induce an autistic phenotype which instead could emerge in response to external events enhancing hippocampal excitability. To address this issue, here we examine to what extent the minor Ambra1 downregulation in male vs female mutant mice, or the constitutively lower Ambra1 levels in male vs female Wt mice might increase the severity of the ASD symptoms triggered by chemogenetic induction of hippocampal hyperexcitability.

Methods

Animals

Manipulations of PV-IN activity were carried out in adult (2/3 months) male PV-Cre_Ambra1+/− (PV_A) male and their PV_Cre wild-type (PV_Wt) male and female siblings obtained from the breeding of Ambra1+/− males with homozygous PV-Cre+/+ females (JAX stock #017320) which selectively express the Cre-recombinase in PV-IN. For genotyping, DNA was isolated from tail tissues and digested at 56 °C in the lysis buffer. DNA amplification and PCR products were analyzed as in [17]. Expression of Cre-recombinase in PV-IN was confirmed by the Jackson Laboratory (https://www.jax.org/) method. Mice were housed in groups of four with sex-matched siblings throughout the experiments, except during procedures requiring isolation like the SIP test. Experiments were conducted using blind randomization and data sampling. Specifically, mice were assigned to groups prior to the experiments using the online random number generator (https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomize1/). Rare exclusions were made prior to testing. Those included mice showing an abnormally low weight, or exhibiting motor/exploratory massive deficit in TC or NOR phase 1, or during the isolation period of the SIP test. Experimenters were blinded throughout, and no retrospective group allocation occurred, adhering to ARRIVE guidelines.

Total protein extraction and Western blot

Hippocampi were dissected from the entire brain and stored at −80 °C until the day of the experiment. Tissue was homogenized in RIPA buffer containing (in mM) 50 Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 NaCl, 5 MgCl2, 1 EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 sodium orthovanadate, 5 b-glycerophosphate, 5 NaF and protease inhibitor cocktail, and incubated on ice for 30 min. The samples were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 min and the protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by the Bradford method. Proteins were applied to SDS–PAGE and electroblotted on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Blotting analysis was performed using a chemiluminescence detection kit. The relative levels of immunoreactivity were determined by densitometry using ImageJ- Primary antibodies: Actin (1:10000; Sigma Aldrich; #A5060; RRID: AB_476738); AMBRA1 (1:1000; Millipore, ABC131, RRID:AB_2636939). Secondary antibodies: goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:3000; Bio-Rad; #1706515; RRID: AB_2617112). All the experimental groups were analyzed simultaneously.

Chemogenetic enhancement of hippocampal excitability

Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of Zoletil (800 mg/kg) and Rompum (200 mg/kg) and DREADD-mediated enhancement of hippocampal excitability was produced by injecting bilaterally the different viral constructs in the dorsal CA1 region of the hippocampus at the following coordinates: antero-posterior from bregma: – 2,2 mm; lateral from midline: ± 1,8 mm; dorsoventrally in each hemisphere (−1.5 mm from the bregma) [31]. For PV-IN manipulations aimed at augmenting excitability by reducing the inhibitory input onto PN, PV_A males and PV_Wt male and female mice were injected with the mutant human inhibitory muscarinic receptor Gi (AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry, #44362, Addgene). For PN manipulations aimed at directly increasing depolarization of PN, Ambra1+/− males and Wt males and females were injected with the excitatory hM3Dq receptor driven by the CamKII promoter (AAV5/CaMKIIa-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry, University of North Carolina Vector Core [32]). DREADD were activated four weeks after injections of the viral constructs by the DREADD ligand Clozapine N-oxide (CNO, 5 mg/kg dissolved in DMSO, C0832 Sigma-Aldrich) that was (i) delivered in the medium 40 min before electrophysiological recordings, (ii) injected i.p. 40 min before behavioral testing, or (iii) diluted at the same concentration in the drinking water 24 h before mice were sacrificed for dendritic spines measurements.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

DREADD specificity was controlled by co-labelling PV or αCamKII with mCherry in 30 μm-thick coronal sections. Primary antibodies were PV (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich; P3088) or αCamKII (1:200; Thermo Fisher; #13-7300). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific; #R37114) or NeuroTrace 435/455 (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific; #N21479). Images were acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM 700; Carl Zeiss AG, Feldbach, Switzerland) and analyzed by means of the ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Brain slicing

Slicing was performed as previously described [17]. Briefly, following halothane anesthesia, mice were decapitated and the brain was rapidly removed from the skull; parasagittal brain slices containing the dorsal hippocampus (280 μm thickness) were obtained with a Leica VT1200S vibratome in chilled bubbled (95% O2, 5% O2) ice-cold sucrose-based solution (containing in mM): KCl 3, NaH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 26, MgSO4 10, CaCl2 0.5, glucose 25, sucrose 185; ~300 mOsm, pH 7.4). After cutting, brain slices were incubated in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; containing in mM): 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 1 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, ~ 300 mOsm, pH 7.4) at 34 °C for 40 min and transferred at room temperature for at least 30 min before recordings.

Patch clamp recordings

A single brain slice was transferred to a recording chamber of an upright microscope (Axioskop 2-FS; Zeiss, Germany) and continuously perfused (3 mL sec−1, 32 °C) with aCSF. The dorsal hippocampus was identified with infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) at 4x magnification; whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from the soma of CA1 pyramidal neurons, identified using a magnification of 60x. All recordings were performed with Axon 700B amplifier using a 4 kHz low pass-filter, digitized at 20 kHz with a Digidata 1400 A and computer-saved using Clampex 10.3 (allf from Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). No liquid junction potential correction was applied. Recording electrodes (3–4.5 MΩ) were pulled from thin-wall borosilicate glass tubes (TW150F-4; World Precision Instruments, Germany) and filled with (in mM): 140 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 2.5 QX314-Cl, 4 Mg-ATP ( ~ 290 mOsm, pH 7.29). The extracellular solution for the recording of inhibitory currents was the above-mentioned aCSF that also contained (in μM) 10 NBQX (Abcam), 50 D-AP5 (Abcam), 1 CGP55845 (Sigma-Aldrich) to block the activity of AMPA/kainate, NMDA and GABAB receptors, respectively. Recordings were carried out before and after CNO (10 μM) applied to bath perfusion. Evoked IPSCs (at − 70 mV holding potential) were recorded using the above-mentioned extracellular solution containing receptor antagonists plus 1 μM WIN55,212-2((R)-(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3-(4-morpholinylmethyl)pyrrolo[1,2,3-de]1,4benzoxazin-6-yl]-1naphthalenylmethanone mesylate; Tocris) to block GABA release from cholecystokinin (CCK) basket cells. Inhibitory currents were evoked by placing the stimulating electrode in the stratum pyramidale, in close proximity to the recorded neuron, to evaluate perisomatic inhibition. The stimulating electrode was a monopolar glass electrode filled with aCSF and stimuli (100 μs duration every 30 s) were applied with an ISOFlex stimulus isolator (A.M.P.I, Israel). Overall, stimulus intensity ranged from 20 to 110 μA. Miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) from hippocampal pyramidal neurons were recorded in voltage-clamp mode (at −70 mV) using the same solutions and drugs as for evoked currents in the presence of bath-applied lidocaine for at least 5 min (500 uM; Abcam) routinely used to block voltage-gated sodium channels. For analysis, one-minute-long analysis window was scanned for the detection of mIPSCs; single events were detected manually using an amplitude threshold crossing method in Clampfit 10.3 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and analysed for amplitude, instantaneous frequency and charge transfer; all parameters were tested for time stability using Spearman’s rank order correlation test and segments of events that showed time instability during the experiment were excluded from further analysis. At least 400 events were analyzed for each condition (pre- and post-CNO) in each patch.

Behavior

Independent mice groups were exposed to the three chambers (TC), the social interaction in pairs (SIP), and the novel object recognition (NOR) tests.

The TC test was run in an apparatus made of three adjacent chambers (70 cm L × 20 cm W × 20 cm H) delimited by Plexiglas walls with an opening at the floor level. The test consisted of 3 phases of 10 min separated by 1-min intervals. In phase 1 (habituation), the test mouse was allowed to freely explore the empty chambers. In phase 2 (sociability), and phase 3 (social novelty), perforated cylinders, empty or containing a wild-type age- and sex-matched conspecific mouse (sociability), or the familiar and a novel age- and sex-matched conspecific mice (social novelty), were placed in the external chambers. The test mouse introduced in the central chamber was left free to enter the external chambers. The total time (s) spent in contact with the empty cylinder or the cylinder containing the conspecific mouse, and with the cylinders containing the familiar and the unfamiliar mice was recorded manually to score sociability and social novelty and the recognition index was calculated as in [16].

The SIP test consisted in introducing for 5 min an unfamiliar Wt female into a standard cage (26,5 cm L x 20,5 cm W, 14 cm H) where the test mouse was reared in isolation for the previous 5 days as in [33]. The total time (s) spent by the test mouse in contact with the unfamiliar Wt female was recorded manually and calculated by summing up the time spent in nose-to-nose, anogenital and body sniffing.

The NOR test was run in a squared Plexiglas cage (40 cm L × 40 cm W × 34 cm H). The test consisted of 3 phases of 5 min each separated 1-min intervals. Mice were placed in the empty cage (phase 1, habituation), successively exposed to two identical objects (phase 2, object exploration), and then to one familiar and one unfamiliar object (phase 3, object novelty). Habituation of exploration in phase 1 was estimated by measuring the distance traveled (cm) and the velocity (cm/s) in the empty arena using Noldus EthoVision XT software. The time (s) in contact with similar objects during phase 2, and the familiar and unfamiliar objects during phase 3, was recorded manually to calculate recognition indexes as in the TC test.

Apparatuses were cleaned with a 10% alcohol solution after the tested mouse was returned to the home cage.

Dendritic spines

Golgi-Cox staining was performed as in [17]. CA1 neurons were identified with a light microscope (Leica DMLB) at low magnification (×20), and dendritic spines were analyzed at higher magnification (×100). Spines were counted on randomly chosen apical 30–50 μm dendritic segments of secondary and tertiary branches of CA1 dorsal pyramidal neurons, excluding regions near the soma and the distal ends. Spines were counted using the computer-based neuron tracing system (Neurolucida; MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT), with 3–5 neurons and 3–5 segments analyzed per mouse. For morphological analyses, we employed the freely accessible RECONSTRUCT software (http://synapses.clm.utexas.edu) [34, 35] to measure the width and length of dendritic spines from previously acquired images by Motic Live Imaging as in [18]. The output data from RECONSTRUCT was then processed through an automated algorithm, which classified the spines based on their morphological parameters —combining width and length according to a custom hierarchical formula previously validated by Risher et al. [35].

Statistics

Input-output curves of eIPSCs at different stimulations were analyzed with 3-way ANOVAs with treatment and stimulus intensity as between-group factors, and repeated measures as the within-group factor. In each genotype, differences in eIPSC amplitude, and in mIPSC amplitude and frequency before and after bath application of CNO were estimated by means of paired t-tests or the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, according to normality. Delta reduction of eIPSC were compared between (i) PV_A males and PV_Wt males, and (ii) PV_Wt females and PV_Wt males using unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction. mIPSC amplitude and frequency were compared in the same groups by Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for cumulative probability plots for inter-event interval and peak amplitude.

Two-way ANOVAs were used to compare recognition indexes (TC and NOR), time spent sniffing (SIP), habituation of motor activity (NOR), and spine density or morphology between (i) PV_A and PV_Wt males injected with CNO or Veh (main factors: genotype and treatment) and (ii) PV_Wt males and females injected with CNO or Veh (main factors: sex and treatment). Paired t-tests were used to compare dual items exploration scores in TC- and NOR- phases 2 and 3 shown in Supplementary figures 1–3. Student’s t-test was used to compare CNO/Veh Sham groups in Supplementary Figure 4.

Data collection and availability

Distributions compared with ANOVAs or paired t-tests were previously tested for normality using the Shapiro’s test. Data collection stopped when sample size was reached. This was determined in each experiment by setting the probability of a Type I error (α) and power at 0.05 and 0.80, respectively as in [18]. Raw data are available, upon request, from the corresponding authors.

Results

PV_Ambra1+/− mice show sex-specific Ambra1 protein reduction and selective DREADD expression in CA1 PV interneurons

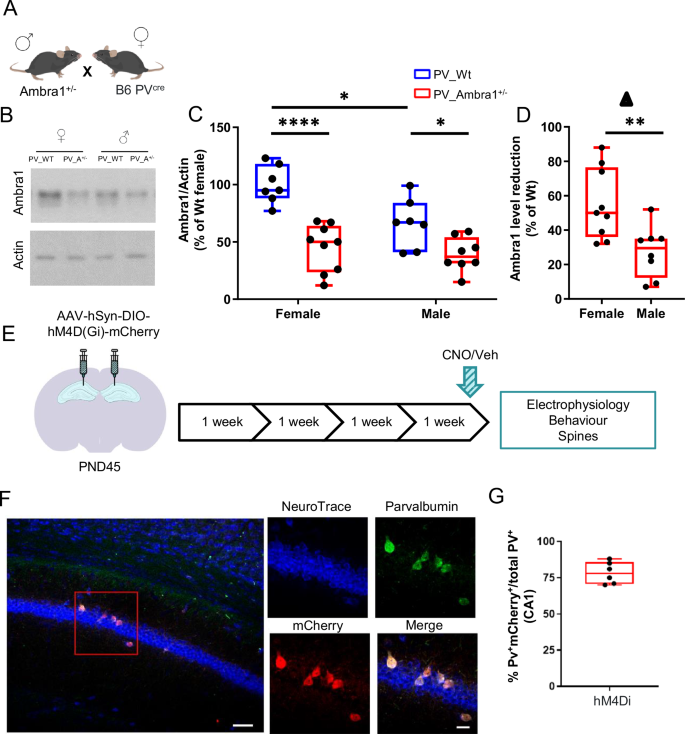

Heterozygous Ambra1+/− mice were crossed with PV-Cre transgenic mice to generate Ambra1_PV-Cre (PV_A) and Wt_PV-Cre (PV_Wt) mice that allows for selective manipulations of PV-IN activity (Fig. 1A). To confirm that hippocampal differences in sex and mutation of Ambra1 protein levels were preserved when Ambra1 haploinsufficiency was expressed in PV_Cre mice, Ambra1 was measured in hippocampal extracts from each experimental group. In line with our report [17], Ambra1 expression was constitutively lower in PV_Wt males than PV_Wt females, and globally lower in PV_A mice than PV_Wt mice, with no difference being observed between PV_A males and PV_A females (Fig. 1B, C). Remarkably, the percentage of Ambra1 reduction from constitutive levels was significantly lower in males than females, thereby demonstrating that the amount of Ambra1 downregulation is stronger in female mutants (Fig. 1D). In mice injected bilaterally with AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry in the dorsal CA1 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 1E) the specific targeting of PV interneurons was controlled by immunofluorescent labeling of slices. Results indicate that about 75% of PV-expressing interneurons showed mCherry expression (Fig. 1F, G).

A Breeding. B Representative western blots from PV_Wt and PV_A female and male hippocampi. C Box and whisker plots show hippocampal levels of Ambra1 protein expression in the four experimental groups. Data are expressed as % of Ambra1 levels from PV_Wt females, normalized to Actin. 2-way ANOVA shows an effect of genotype (F(1, 27) = 38.02, P < 1 × 10−4), sex (F(1, 27) = 8.76, P = 0.006, and of genotype x sex interaction (F(1, 27) = 4.39, P = 0.04). Ambra1 was constitutively more expressed in PV_Wt females (n = 7) than PV_Wt males (n = 7), P < 0.05, and significantly decreased in PV_A females (n = 9) compared to both PV_Wt females (P < 1 × 10−4)) and PV_Wt males (P = 0.010). Ambra1 was also significantly decreased in PV_A males (n = 8) compared to PV-Wt males (P = 0.040) but similarly expressed in PV_A males and PV_A females (Tukey’s test post hoc pair comparisons). D Box and whisker plots depicting the percentage reduction of Ambra1 expression from constitutive levels in PV_A mice of both sexes. Downregulation of Ambra1 expression was significantly stronger in PV_A females than PV_A males (P < 0.01). E Experimental design: AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry was bilaterally inoculated in the dorsal hippocampal CA1 region. Experiments started four weeks later. Vehicle (VEH) or CNO were injected i.p. 40 min before behavioral testing and electrophysiological recordings, or diluted at the same concentration in the drinking water 24 h before mice were sacrificed for dendritic spine analyses. F Left panel: low magnification image depicting in situ stereotaxic inoculation of AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry in dorsal CA1 hippocampus, scale bar: 50 μm. Right panels: representative images of CA1 NeuroTrace/PV/mCherry labeling showing overlapping signals (yellow) of mCherry (red) and Parvalbumin interneurons (PV-IN) (green). Scale bar: 20 μm. G Percentage estimation of PV-IN infected with the hM4Di AAV (PV+mCherry+/total PV+). In box-and-whisker plots, the central line denotes median value, edges are upper and lower quartiles, whiskers show minimum and maximum values. Points are individual experiments (N = 6 for hM4Di). Data are plotted as mean ± s.e.m. Post hoc pair comparisons *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

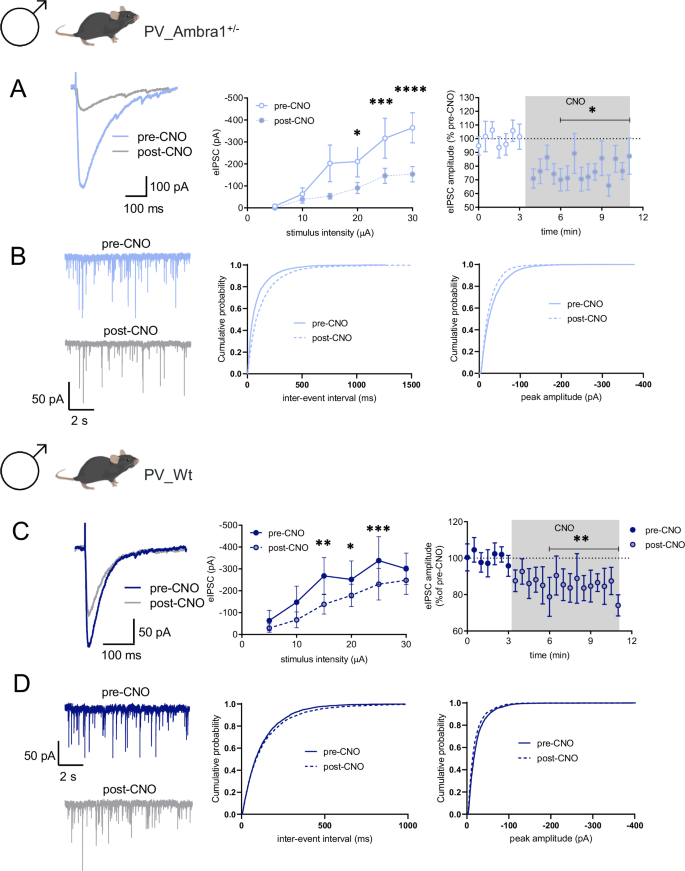

Chemogenetic inhibition of PV-IN in Ambra1+/− and Wt male mice reduces GABAergic currents onto CA1 PN

To confirm the CNO-induced chemogenetic inhibition of PV-INs, we recorded perisomatic evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs) from CA1 PNs of PV_A and PV_Wt male mice. Given that perisomatic inhibition of PNs derives not only from PV-INs but also from fast-spiking cholecystokinin (CCK) cells, we pharmacologically blocked the release of GABA from CCK cells by WIN55,212-2 (1 μM), an agonist of cannabinoid CB1 receptors that is expressed by CCK but not PV-INs [36]. Pre- and post-CNO recordings of eIPSCs on PNs following stratum piramidale stimulation showed that bath application of CNO (10 μM) reduced the amplitude of recorded eIPSCs in both PV_A males and PV_Wt males (Fig. 2A, C), thereby indicating that activation of the inhibitory DREADD by CNO selectively blocks the inhibitory activity of PV-INs. Importantly, the effect of CNO was similar, regardless of genotype. In line with these data, CNO also reduced the frequency and/or amplitude of miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) recorded from PNs (Fig. 2B, D).

A The traces show eIPSCs before and after bath application of CNO (10 μM), from CA1 PNs (held at −70 mV) from PV_A male mice inoculated with AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry. The left plot shows the input-output relationship of eIPSCs at different stimulation intensities (n = 9 neurons, 2-way (repeated stimulus x treatment) ANOVA; interaction F(5,40) = 7.33, P = 1 × 10−4; stimulus F(5,80) = 21.88, P < 1 × 10−4; treatment F(1,8) = 5.77, P = 0.043 with Bonferonni’s post-hoc test). The right plot shows the effect of CNO on eIPSC amplitude at half-maximal stimulation. The gray panel shows the duration of CNO application (n = 10 neurons, *P = 0.032 with paired t-test). B Traces show paired recordings of miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) before and after bath application of CNO (10 μM) from PV_A males inoculated with AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry. The plots show cumulative probability plots for inter-event interval and peak amplitude (9 neurons, inter-event interval P < 0.0001, peak P < 0.0001 with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). C Paired eIPSCs before and after bath application of CNO from PV_Wt males inoculated with AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry. The left plot shows the input-output relationship of eIPSCs at different stimulation intensities (n = 8 neurons, 2-way RM-ANOVA, Interaction F(4,28) = 3.06. P = 0.033, stimulus F(4,28) = 10.37, P < 1 × 10−4; treatment F(1,7) = 6.31; P = 0.040, pair comparisons **P = 0.001, *P = 0.029, ***P = 7 × 10−4 with Bonferonni’s test). The right plot shows the effect of CNO on eIPSC amplitude at half-maximal stimulation (n = 11 neurons, *P = 0.009 with paired t-test). D mIPSCs before and after bath application of CNO (10 μM), from PV_Wt inoculated with AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry. The plots show cumulative probability plots for inter-event interval and peak amplitude (7 neurons, inter-event interval P = 0.0601, peak P < 0.0001 with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). A–D. The effect of CNO showed similarity between PV_A males and PV_Wt males. Specifically, there is no discernible variance in genotype effects between PV_A males and PV_Wt males, evident in the delta reduction of eIPSC [t(18,8) = 0.65, P = 0.5244] (A, C), and neither in the frequency nor in the amplitude [Two-way ANOVA repeated measures: frequency: genotype effect = ns, F(1,14) = 0.64, P = 0.44; amplitude: genotype effect: ns, F(1, 14) = 0.3, P = 0.6] (B, D).

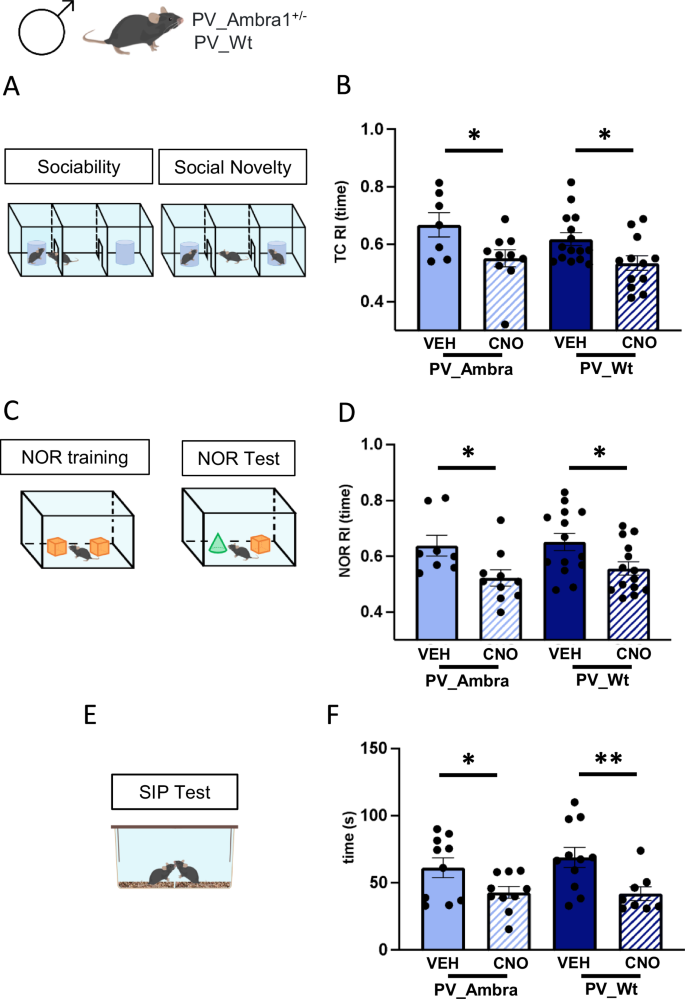

Acute chemogenetic inhibition of PV-IN triggers social and attentional deficit in male mice regardless of mutation

Although the Ambra1 haploinsufficiency is not per se sufficient to induce ASD traits in male mice, it could nonetheless underlie a stronger propensity of male mice to develop autistic-like phenotype in response to events increasing hippocampal excitability. We examined this possibility by comparing the effect of chemogenetic augmentation of CA1 excitability in Wt and mutant males. Inhibitory DREADD infused in dorsal CA1 of PV_A and PV_Wt males were activated by CNO i.p. injections 40 min before exposing mice to three chamber (TC), novel object recognition (NOR), and social interaction in pair (SIP) tests which tackle each specific dimension of sociability and attention typically altered in ASD (Fig. 3A–F, see Methods section for detailed description of the behavioral procedures). In TC phase 2 (sociability), all groups explored significantly more a stranger mouse (S1) than a neutral object (O1) (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). Differently in TC phase 3 (social novelty), a significant decrease in recognition index (Fig. 3B) and the absence of a significant difference in the time spent exploring the familiar (S1) and novel (S2) females (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D) revealed a social novelty impairment in CNO-injected mice regardless of the mutation. In NOR phase 1 (habituation to the empty open field) and phase 2 (training), the distance traveled and velocity (Supplementary Fig. 1E), and the exploration of identical objects (Supplementary Fig. 1F, G) did not significantly vary among groups. Differently in NOR phase 3, a significant decrease in recognition index (Fig. 3D) and the absence of a significant difference in the time spent exploring the familiar (O1) and novel (O2) objects (Supplementary Fig. 1H, I) revealed a NOR impairment in CNO-injected males regardless of mutation. In the SIP test, CNO-injected PV_A and PV_Wt spent less time interacting and sniffing a stranger mouse introduced in their home cage compared to VEH-injected groups (Fig. 3F). To control side effects of CNO on mice behavior, we ran additional experiments using Wt mice lacking DREADDs (Wt_Sham), i.p. injected with CNO or Veh, and exposed to the TC and NOR test. Remarkably, Wt_Sham i.p. injected with CNO or Veh performed similarly in the TC and NOR test, thereby excluding any side effect of CNO per se on behavior (Supplementary Fig. 4A, B).

A Three-chamber (TC) test protocol. B Histograms show mean value of the recognition index (RI) calculated in the social novelty phase of the TC test in PV_A and PV_Wt males injected with vehicle (VEH) or CNO. Reactivity to social novelty was significantly impaired in CNO-injected mice regardless of genotype [2-way ANOVA, treatment: F(1,40) = 11.5 P = 0.002, genotype: ns; PV_A/CNO (n = 10) vs PV_A/VEH (n = 7), P = 0.016; PV_Wt/CNO (n = 12) vs PV_Wt/VEH (n = 15), P = 0.021 with Fisher LSD post hoc test. C Novel object recognition (NOR) protocol. D Histograms show mean value of RI calculated in the NOR test phase in same groups. Novel object recognition was impaired in CNO-injected mice regardless of genotype [treatment: F(1,42) = 11.62, P = 0.001, genotype: ns; PV_A/CNO (n = 10) vs PV_A/VEH (n = 8), P = 0.021; PV_Wt/CNO (n = 14) vs PV_Wt /VEH (n = 14), P = 0.017 with Fisher LSD post hoc test]. E Social interaction in pair (SIP) protocol. F Histograms show mean time spent exploring a stranger age-matched mouse during the SIP test. Social interactions were decreased in CNO-injected mice regardless of genotype [treatment: F(1,35) = 11.85, P = 0.002, genotype: ns; PV_A/CNO (n = 10) vs PV_A/VEH (n = 10), P = 0.05; PV_Wt/CNO (n = 8) vs PV_Wt/VEH (n = 11), P < 0.01 with Fisher LSD post hoc test]. Data are plotted as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The similarity of scores recorded in CNO-injected PV_A and PV_Wt males in the three tasks they were exposed to, excludes that the mild downregulation of Ambra1 levels in mutant males underlies a latent ASD risk.

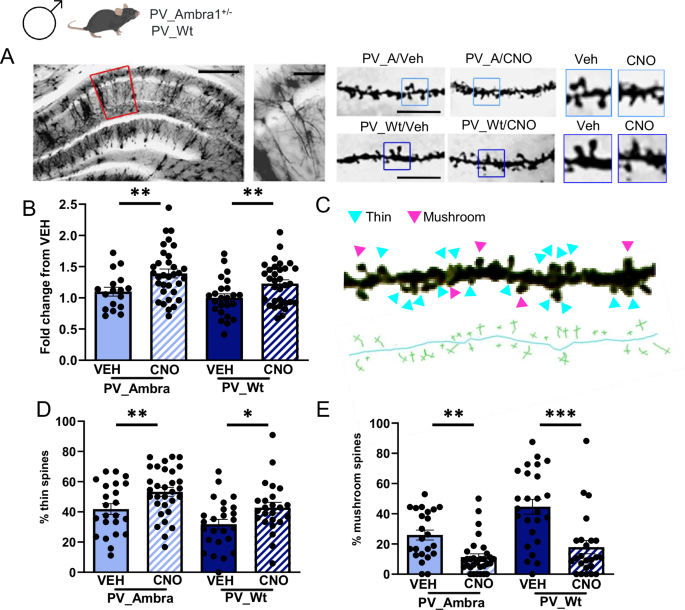

Prolonged chemogenetic inhibition of PV-IN triggers ASD-typical hippocampal spine dysgenesis in male mice regardless of mutation

The proliferation of dendritic spines with an immature morphology is an endophenotype of neurodevelopment disorders [37]. Augmentation in filopodia-like thin spines concurrently with a decrease in mature mushroom spines has been regularly observed in ASD patients and genetic mouse models [38, 39]. In general, spines alterations were detected in relation to mutations in genes implicated in spine structure, maturation and plasticity [40]. More recently, the report that mTOR-linked ASD genes are implicated in the regulation of spine dynamics [41] revealed that pro-autophagic genes also contribute. Given the absence of spine dysgenesis in non-autistic males [17], we verified whether chemogenetic elevation of hippocampal excitability which elicits ASD symptoms could promote ASD-typical spines in this same region. Spine measurements were carried out in Golgi-stained CA1 pyramidal neurons from CNO/Veh-drinking PV_A and PV_Wt male mice. Results showed that CNO-treated groups showed the same proliferation of spines (Fig. 4A, B) and, based on the analysis of spine head diameters (Fig. 4C), the same increase in the percentage of immature thin spines (Fig. 4D) with concurrent reduction in the percentage of mature mushroom spines (Fig. 4E). These findings demonstrate that hippocampal hyperexcitability trigger ASD-typical spines in the hippocampus and that Ambra1 downregulation does not exacerbate spine alterations detected in CNO-drinking PV_Wt males.

A Representative Golgi-stained dorsal hippocampal section from a male Wt control mouse. Left panels: area of dendritic spines measurement (5x magnification, scale bar: 250 μm; 20x magnification, scale bar: 50 μm). Right panels: dendritic spines magnification (100×, scale bar: 5 μm) and zoom of the same sections. B Histograms show mean spine density counted in PV_A and PV_Wt males expressed as fold change of CNO-drinking groups from vehicle (VEH)-drinking goups [PV_A/VEH (17 neurons), PV_A/CNO (33 neurons), PV:Wt/VEH (24 neurons), PV_Wt/CNO (32 neurons)]. Spine density was increased in CNO-drinking mice regardless of genotype [2-way ANOVA, treatment: F(1,102) = 13.78, P = 0.0001, genotype: ns; PV_A/VEH vs PV_A/CNO, P = 0.006; PV_Wt/VEH vs PV_Wt/CNO, P = 0.01; PV_A/CNO vs PV_Wt/CNO, ns]. C Enlarged 100× magnification of a representative dendritic segment (23,57 μm) from a CA1 pyramidal neuron. Pink arrows indicate mushroom spines and blue arrows thin spines. Below, the skeleton of the same dendritic segment with the visualization of the length and head diameter for each spine category. This image has undergone post-production and stack merging with various focus points. Being exclusively designed to enhance clarity of the classification method, it does not depict spines counted in any experimental subject. D, E Histograms show the percentage of thin (D) and mushroom (E) spines in the four experimental groups [PV_A/VEH (3 mice, 6 neurons, 23 segments), PV_A males/CNO (4 mice, 8 neurons, 31 segments), PV_Wt/VEH (3 mice, 6 neurons, 25 segments), PV_Wt/CNO (3 mice, 6 neurons, 24 segments)]. Thin spines were increased, and mushroom spines decreased, in CNO-drinking mice regardless of genotype [Thin spines: treatment F(1,99) = 11.65, P = 0.001, genotype (ns); PV_A/VEH vs PV_A/CNO, P = 0.01; PV_Wt/VEH vs PV_Wt/CNO, P = 0.02; Mushroom spines: treatment F(1,99) = 30.95, P = 0.0001, genotype (ns); PV_A/VEH vs PV_A/CNO, P = 0.005 ; PV_Wt/VEH vs PV_Wt/CNO, P = 0.0001]. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. LSD Fisher post hoc pair comparisons, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

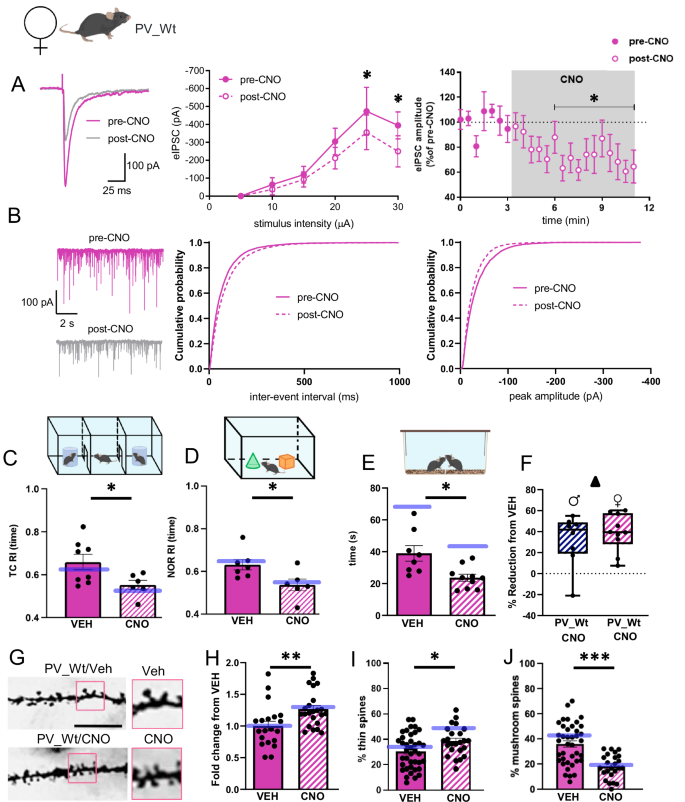

Chemogenetic inhibition of PV-IN in Wt females recapitulates the autistic phenotype of CNO-injected Wt males

Having shown that DREADD-mediated inhibition of PV-IN activity is sufficient to trigger autistic traits in non-autistic males regardless of mutation, we completed our investigation by carrying the same manipulations in non-autistic PV_Wt females. Pre-post recordings from PN showed that CNO injections produced the same reduction of eIPSCs and mIPSCs amplitude in PV_Wt females as it did in PV_A and PV_male mice, overall indicating that activation of inhibitory DREADD in CA1 similarly and selectively blocks the inhibitory input of PV-IN on PN in the three non-autistic groups regardless of mutation or sex (Fig. 5A, B). Histograms below (Fig. 5C–J) show data from PV_Wt females injected with VEH or CNO. On the same histograms, blue lines indicate the scores of PV_Wt males that were previously displayed in Fig. 3B, D and F (behavioral measurements), and in Fig. 4B, D and E (spine measurements). Statistical comparisons were carried out between these two groups to check for a single effect of sex. When tested for sociability and attention, VEH- and CNO-injected PV_Wt females exhibited the same pattern of intact vs impaired behaviors shown by VEH- and CNO-injected PV_Wt males. Specifically, sociability in TC phase 2 (Supplementary Fig. 2A) and exploration of similar objects in NOR phase 2 (Supplementary Fig. 2D) did not vary between VEH- and CNO-injected PV_Wt females. Differently, this latter group showed a decreased reactivity to social (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. 2B) and to object (Fig. 5D and Supplementary Fig. 2E) novelty during TC- and NOR-phase 3 respectively, and a reduction of social interactions in the SIP test (Fig. 5E). Statistical comparisons of behavioral scores between PV_Wt females and PV_Wt males (blue lines) never reached levels of significance, except in the SIP test where VEH-injected PV_Wt females spent less time in contact with their conspecific than VEH-injected PV_Wt males (blue line) (Fig. 5E). If the observation that PV_Wt males is consistent with the report that males tend to interact more with a conspecific [42], the finding that the percentage reduction in exploration time do not vary between CNO-injected PV_Wt females and PV_Wt males (Fig. 5F) reveals the same CNO-induced decrease in SIP performance regardless of sex. Dendritic spines analyses showed that CNO-drinking PV_Wt females showed the same ASD-typical spine abnormalities as CNO-drinking PV_Wt males. Abnormalities consisted in a proliferation of spines (Fig. 5G, H) with reduced head diameters (thin spines) (Fig. 5I) and concurrent diminution of mushroom spines (Fig. 5J). Statistical comparisons between PV_Wt females and PV_Wt males (blue lines) revealed the same spine scores in the VEH condition, and the same decrease from VEH levels following CNO injections.

A The traces show eIPSCs before and after bath application of CNO (10 μM), from CA1 pyramidal neurons (held at −70 mV) from PV_Wt females inoculated with AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry. The left plot shows the input-output relationship of eIPSCs at different stimulation intensities (n = 8 neurons, 2-way ANOVA, Interaction, F(4,28) = 2.02, P = 0.119; stimulus F(4,28) = 11.64, P < 1 × 10−4; treatment F(1,7) = 3.51, P = 0.011 with Bonferonni’s post-hoc test). The right plot shows the effect of CNO on eIPSC amplitude at half-maximal stimulation. The grey panel shows the duration of CNO application (n = 9 neurons, P = 0.012 with Wilcoxon matched-pairs test). B Traces show paired recordings of mIPSCs before and after bath application of CNO (10 μM) from PV_Wt females injected with AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry. The plots show cumulative probability plots for inter-event interval and peak amplitude (7 neurons, inter-event interval P < 0.0001, peak P < 0.0001 with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). A, B. The impact of CNO treatment was analogous in PV_Wt females and PV_Wt males. No significant variations are detected between sexes in A delta reduction of eIPSC [t(16) = 0.8, P = 0.45], B frequency and amplitude [Two-way ANOVA repeated measures: frequency: effect of sex = ns, F(1, 12) = 9.157, P = 0.56; amplitude: effect of sex = ns, F(1, 12) = 1.604, P = 0.23 between PV_Wt females and PV_Wt males. C Histograms show the mean recognition index (RI) calculated during the social novelty phase of the TC test. The blue line represents scores of PV_Wt male mice. PV_Wt/CNO females (n = 6) show social novelty impairments compared to PV_Wt/VEH females (n = 8) [treatment: F(1, 37) = 10.72, P = 0.002. PV_Wt/CNO vs PV_Wt/VEH females, P = 0.03 with Fisher LSD post hoc test]. Of note, no effect of sex was reported [sex: F(1, 37) = 0.99, P = 0.326]. D Histograms show the mean recognition index (RI) calculated during the NOR test phase. The blue line represents scores of PV_Wt males. Novel object recognition was impaired in PV_Wt/CNO females (n = 6) compared to PV-Wt/VEH females (n = 7), [treatment: F(1, 37) = 10.28, P = 0.003; PV_Wt/CNO (n = 6) vs PV_Wt/VEH (n = 7) females, P = 0.04 with Fisher LSD post hoc test]. Of note, no effect of sex was reported [sex: F(1, 37) = 0.42, P = 0.5]. E Histograms show the mean time spent exploring an unknown female conspecific during the social interaction in pair test (SIP). The blue lines represent scores of PV_Wt males. PV_Wt/CNO females show less social interactions than PV_Wt/VEH females. [treatment: F(1, 33) = 14.48, P = 0.001; PV_Wt/CNO (n = 10) vs PV_Wt/VEH (n = 8) females, P = 0.04 with Fisher LSD post hoc test]. Males show more sociality than females [sex: F(1, 33) = 19.53, P < 0.001; PV_Wt/VEH females vs PV_Wt/VEH males, P < 0.001; PV_Wt/CNO females vs PV_Wt/CNO males, P = 0.03. F Box and whisker plots depicting the relative reduction in exploration time induced by CNO in PV_Wt females and PV_Wt males. No differences are detected between the two groups t(16) = 0.7, P = 0.5. G Representative dendrites obtained from a Golgi-stained dorsal hippocampal section in a Wt control female. On the left, 100× magnifications (scale bar: 5 μm) with zoom of the same sections on the right. H Histograms show the mean spine density in PV_Wt females exposed to CNO, expressed as fold change from vehicle (VEH). The blue lines represent scores of PV_Wt males. CNO-drinking Wt females showed an increase in spine density compared to VEH-drinking females [PV_Wt/VEH (20 neurons), PV_Wt/CNO (23 neurons); treatment: F(1, 95) = 14.58, P < 0.001; PV_Wt/CNO vs PV_Wt/VEH females, P = 0.007 with Fisher LSD post hoc test]. No effect of sex was found [sex: F(1, 95) = 0.08, P = 0.77]. I, J Histograms show the percentage of thin I and mushroom J spines in the same groups [PV_Wt/VEH females (4 mice, 9 neurons; 39 segments); PV_Wt/CNO females (3 mice, 5 neurons, 24 segments)]. CNO-drinking PV-Wt females showed an increase in thin spines, and a decrease in mushroom spines, compared to VEH-drinking PV_Wt females [Thin spines: treatment: F(1, 108) = 11.4, P = 0.001; PV_Wt/CNO vs PV_Wt/VEH females, P = 0.034 with Fisher LSD post hoc test]. No effect of sex was reported [sex: F(1, 108) = 0.99, P = 0,3]. Mushroom spines: F(1, 108) = 39.98, P < 0.001; PV_Wt/CNO vs PV_Wt/VEH females, P < 0.001 with Fisher LSD post hoc test]. No effect of sex was found [sex: F(1,108) = 1.44, P = 0.2]. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

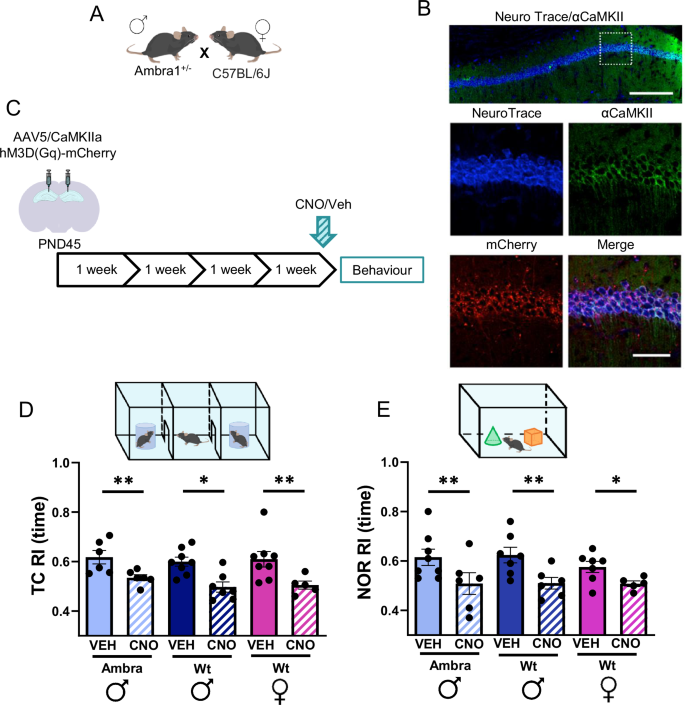

Chemogenetic increase of CA1 PN activity replicates social and NOR impairments produced by chemogenetic decrease of CA1 PV-IN activity

Although PV-INs represent only 25% of CA1 GABAergic interneurons [43], their dense pattern of innervation [44] candidates them as the principal regulators of synaptic inhibition onto CA1 PN. To confirm that PV-IN are key players in upregulating CA1 excitability and triggering autism in Ambra1+/− males and Wt mice of both sexes, we examined whether chemogenetic manipulations that augment CA1 PN activity could trigger sociability and attentional deficits similar to those triggered by decreasing PV-IN activity. An AAV expressing the activatory hM3Dq receptor driven by the CamKII promoter was injected in situ in the CA1 region of hippocampus of Ambra1+/− males and Wt mice of both sexes (Fig. 6C). CNO was injected 40 min before mice were exposed to the TC and NOR tests. All CNO-injected mice showed the same preservation of sociability in TC phase 2 (Supplementary Fig. 3A–C) and of object exploration in NOR phase 2 (Supplementary Fig. 3G–I), but the same impairment in detection of social novelty in TC phase 3 (Fig. 6D and Supplementary Fig. 3D–F) and of object novelty in NOR phase 3 (Fig. 6E and Supplementary Fig. 3J–L) exhibited by CNO-injected PV-Cre mice undergoing chemogenetic inhibition of CA1 PV-IN activity.

A Breeding. B Representative images of NeuroTrace/CamKII/mCherry labeling showing overlapping signals of mCherry (red) and CamKII- neurons (green). hM3Dq receptors are selectively expressed in CA1 principal neurons. Scale bars: top, 200 μm; below, 50 μm. C Experimental design: the rAAV5/CaMKIIa-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry vector was bilaterally inoculated in the dorsal CA1 region of Ambra1+/− males and Wt mice of both sexes. Behavioral tests were performed 4 weeks later. Vehicle (VEH) or CNO were injected i.p. 40 min before testing. D Histograms show the mean recognition index (RI) calculated in the social novelty phase of the TC test. Reactivity to social novelty was impaired in CNO-injected mice regardless of group [2-way ANOVA, treatment: F(1,34) = 24.9, P = 0.001. Group: ns; A/VEH males (n = 6) vs A/CNO (n = 6) males, P = 0.002; Wt/VEH males (n = 8) vs Wt/CNO males (n = 7), P = 0.02; Wt/VEH females (n = 8) vs Wt/CNO females (n = 5), P = 0.004 with Fisher LSD post hoc test]. E Plots show the mean recognition index (RI) calculated in the NOR test phase. Novel object recognition was impaired in CNO-injected mice regardless of group [treatment: F(1,33) = 17.84, P = 0.001, Group: ns; A/Veh males (n = 8) vs A/CNO males (n = 6), P = 0.01; Wt/VEH males (n = 7) vs Wt/CNO males (n = 6), P = 0.01; Wt/VEH females (n = 7) vs Wt/CNO females (n = 5), P = 0.05]. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Dysfunctions in the GABAergic system contribute to neurodevelopmental disorders by altering the functional maturation of cortical and subcortical regions involved in cognition, emotions, and socialization [45, 46]. In ASD, an association between autistic traits and deficiency in genes which control ubiquitous development of GABAergic PV-INs has been extensively reported [47]. Within this context, Ambra1 is one rare example of pro-autophagic gene whose heterozygous deletion decreases PV-IN density in the hippocampus and triggers autistic traits exclusively in the female sex [17]. Having shown that chemogenetic rectification of hippocampal E/I balance in Ambra1+/− females rescues their autistic phenotype [18], this study investigates the possibility that susceptibility factors insufficient to induce an autistic phenotype – like non-pathogenic downregulation of Ambra1 levels and/or sex – might underlie a latent predisposition to show autistic traits in response to external events triggering hippocampal hyperexcitability.

Ambra1 downregulation in male mutants does not exacerbate their reactivity to chemogenetic induction of idiopathic ASD

Our findings show that CNO-injected PV_A and PV-Wt male mice exhibit the same DREADD-mediated reduction of the inhibitory input onto CA1 PN, and exhibit indistinguishable ASD-typical behavioral and dendritic spines alterations. A point to be noticed is that Wt males, differently from Wt females, do not show any decrease in hippocampal PV expression or estrogen receptor levels neither during development, nor after treatments decreasing sex hormones like castration or testosterone/dihydrotestosterone injections [48]. Although these findings might suggest that their inhibitory circuits are more stable and potentially less susceptible to be altered by mutations which trigger E/I unbalance, data from the literature do not support this possibility. For example, heterozygous deletion of TSC1, TSC2, PTEN or FMR1 genes which, like Ambra1, are key components of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 cascade, all trigger autistic traits regardless of sex [49, 50]. Even when a sex bias was observed like in heterozygous Cc2d1a mice, reduction in cortico-hippocampal autophagy markers and manifestation of autistic symptoms were only statistically more frequent in males than females [51]. In contrast with these data, Ambra1 heterozygous deletion restricts the autistic phenotype to Ambra1+/− females despite Ambra1 is comparably expressed in the hippocampus of mutant mice of both sexes [16, 17]. It is therefore apparent that the resilience of male mice to Ambra1 deficiency cannot be ascribed to their absolute Ambra1 levels, but their minor downregulation from constitutive levels.

Constitutive sex differences in Ambra1 levels do not underlie a differential reactivity to chemogenetic induction of idiopathic ASD in wild-type mice

DREADD-mediated augmentation of CA1 excitability trigger similar behavioral, electrophysiological, and dendritic spine ASD-like alterations in Wt males and females despite CA1 microcircuits differ anatomically and functionally between sexes [52]. Specifically, the report that ERβ receptors co-localize with PV cells in the hippocampus of female rats reveals a female-specific mechanism by which estrogen regulates hippocampal neuronal excitability via modulation of the inhibitory tone [53]. Confirming the steroid modulation of female hippocampal inhibitory circuits, Wu et al. [48] observed that ovariectomy decreases PV/GAD67 co-localization in the hippocampus, and that this sex-specific alteration is restored by 17b-estradiol supplementation. Interestingly, comparison of the developmental trajectory of PV/GAD67 hippocampal expression showed that only females show a progressive augmentation of PV/GAD67 co-localization with age [48] suggesting that a stronger inhibitory input is necessary to maintain physiological levels of excitability in the adult female hippocampus. In their whole, these findings indicate that hippocampal inhibitory circuits are less stable in Wt females than males, and hence require higher levels of autophagy to remain in a functional state. Indeed, the constitutively higher levels of Ambra1 expression in the hippocampus of Wt females align with this possibility. However, if differences of Ambra1 levels are tailored to stabilize physiological levels of CA1 excitability in Wt mice of each sex, these differences are expected to serve the same neuroprotective function, which has therefore the same probability to be impaired by events enhancing hippocampal excitability. This might explain why despite their robust constitutive differences in hippocampal Ambra1 levels, male and female WT mice are both prone to exhibit autistic traits in response to events which trigger hippocampal hyperexcitability, consistently with a minor role of sex in environment-driven idiopathic ASD.

Conclusions

Sex differences in autism are fundamental to identify factors which render males and females statistically more protected or vulnerable allowing, in turn, to define gender-specific criteria for diagnosis, prevention, and therapy [54, 55]. Within this context, the sexual strict dimorphism of autistic traits triggered by Ambra1 haploinsufficiency authorizes to draw general conclusions on ASD risks from molecular/neurobiological alterations specific to the sex.

For example, given the mounting interest into the contribution of autophagy to ASD [56,57,58,59], our observation that it is the sex-relative decrease, and not the absolute level, of Ambra1 protein which associates, or does not associate, to autistic symptoms, contributes to refine the role played by hippocampal regional Ambra1 variations in ASD. Also, by demonstrating that chemogenetic manipulations of GABAergic interneurons or principal pyramidal neurons result equivalent in augmenting CA1 excitability and triggering autistic traits in all asymptomatic mice groups, our findings (i) reveal that CA1 GABAergic PV-IN, despite their low density (25%) in the broad network of rodent hippocampal interneurons [43], finely regulate hippocampal network activity (ii) show that PV-IN and PN provide alternative sites for therapeutic rectification of hippocampal hyperexcitability, and (iii) definitely confirm the causal role of local hippocampal E/I unbalance impacting spine dysgenesis [60] in ASD, even though E/I unbalance in other regions [5, 6] might also contribute.

Indeed, the observation that none of the non-pathogenic fluctuations in Ambra1 levels exacerbate the DREADD-induced ASD phenotype raises the possibility that the severity of acute CA1 DREADD manipulations overwhelm any latent ASD risks. Although this hypothesis cannot be entirely discarded, the robust differences in Ambra1 levels between groups, especially between Wt females vs mutant males, suggest that there is room for a differential reactivity to DREADD manipulations.

As previously outlined [61], analyses of ASD risks deriving from genotype x environmental interactions have to be completed by investigating the contribution of adverse conditions experienced early in development. Within this context, exposing asymptomatic mice to perinatal stress [62], neurotoxins [8, 63], or pro-inflammatory factors [64] which elicit idiopathic ASD associated with hippocampal hyperexcitability via a decrease in PV+ interneurons activity [5] should allow to go further in estimating how non-pathogenic Ambra1 fluctuations enhance idiopathic ASD risks.

Responses