Chinese glass ornaments from the port site of Shuo Gate, Zhejiang, China, 10th–13th Century CE

Introduction

Today, ancient China is often regarded as the “Country of Clothes and Hair Ornaments” due to considerable archaeological finds that demonstrate the tradition of focusing on dress and hair decoration. These artefacts reflect the practical use, social status, and aesthetic spirit of ancient Chinese people. Hairpins, used for stabilizing hats or long hair of both men and women, are among the most common hair accessories in the history of China. In Chinese, hairpins were called “Ji (笄)”, “Zan (簪) ” or “Chai (钗)”. In the Han dynasty in the first millennium BCE, Ji was made of bamboo with one sharp end. Ji played an important role in the coming-of-age of Chinese women. When a girl turned 15 year old, she stopped wearing braids, and a hairpin ceremony called “Ji Li” (笄礼), which means hairpin initiation, would be held to celebrate the rite of passage. During the ceremony, their hair would be coiled into a bun with a ji hairpin. After the ceremony, the woman would be eligible for marriage1,2.

As early as the Neolithic Age, hairpins made of bone, horn, and precious stone were widely used at Hemudu sites, which date between the 7th and 5th millennia BCE3. During the Qin and Han dynasties (3rd century BCE – 3rd century CE), more precious materials, including gold, silver, rhinoceros horn, jade, and glass, were selected for hairpins which presented the owner’s social status2. In the Song and Yuan dynasties, between the 10th and 14th centuries CE, there was a notable increase in the popularity of colourful glass hairpins for decoration, as evidenced by many archaeological discoveries across Chinese sites from north to south. Most glass pins have been excavated from tomb chambers in regions ranging from northern China, such as Hebei4, Shandong5 and Inner Mongolia province6, to southern China, including Zhejiang7, Jiangxi8, Jiangsu9 and Fujian Province10, etc.

This paper focuses on the glass fragments in hairpin shapes excavated from the ancient port site Shuo Gate (朔门), located north of Wenzhou (温州) city in Zhejiang province, adjacent to the south bank of the Ou River flowing into the East China Sea (Fig. 1). Archaeologists from the Wenzhou Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Archaeology have been excavating the site since October 2021 and have discovered architectural remains related to water locks and land gates of ancient Wenzhou city, eight piers, three shipwrecks, one wooden plank road, and numerous porcelain sherds.

The Shuo Gate port site, dating from the 10th–13th century AD, is marked with a red spot. (28°01’27.2“N, 120°39’13.1“E).

Seventeen pieces of hairpin glass fragments in blue, white and green colours were found (Fig. 2). These remains are primarily dated from the Song to Yuan Dynasty and continued into the period of the Republic of China. The excavations vividly illustrate the grand historical scene of the ancient port and provide critical evidence that Wenzhou was a starting port for exporting Longquan porcelain and an important node on the Maritime Silk Road11. The site was elected as “one of the top ten archaeological discoveries of 2022” by the China Archaeology Society.

Seventeen pieces of glass hairpin find.

Although glass ornaments like beads or hairpins are frequently discovered at archaeological sites, only few scientific analyses have been applied on the glass material. A piece of glass vessel fragment from Nanhai Shipwreck No. I sank at South China Sea, dating to the late Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279 CE), was analysed and classified as K2O-PbO-SiO2 glass with fluorite dendrites (CaF2) as opacifier12. Another study analysed six glass samples, including hairpins, adornments, and a chess piece, from Lindong town in Inner Mongolia, the capital city of the Liao Dynasty (918–1120 CE)6. Furthermore, research using ICP-AES on the earliest discovered glassmaking site in Yanshangzhen county, Zibo city, showed that K2O-CaO-SiO2 glass continued to be produced during the 12th to 14th centuries CE13.

Scientific studies on Chinese archaeological glass typically use XRF, SEM-EDS, and ICP-AES for chemical analysis. In this paper, LA-ICP-MS was employed on Chinese glass materials for the first time, obtaining compositional results of 57 elements within the glass matrix to provide a more comprehensive characterization of each sample. Future studies on Chinese glass can reference these results for future comparison. Additionally, advanced scientific method such as micro-CT is employed to investigate the inner structure of this unique type of glass ornament from the Song dynasty. Combining archaeological context with scientific analysis, Chinese glass reflects not only the consumption and aesthetic views of contemporary people but also the unique manufacturing and distribution processes within the global glass civilization.

Materials

Archaeologists found seventeen monochrome fragments of glass hairpins at the third cultural layer of site pit TN07E12, which was dated to the Southern Song dynasty (1127 CE–1279 CE). The assemblage was categorized into five different types: eleven blue opaque, two white opaque, two green opaque, one dark-green opaque, and one blue transparent. Consequently, five specimens, each representing one of the specific colours, were selected for a series of scientific analyses. Table 1 lists descriptions of the five samples.

Glass hairpins, ranging in length from approximately 12 to 19 cm, can be conceptually divided into three main parts: head, body, and foot. Typically, there are two types of hairpins: a single stick with a decorated head and a sharp foot or point, known as “Zan (簪)”, and a two-leg hairpin made in a “U shape” with two sharp feet, called “Chai (钗)”. The both types were used to secure and adorn various hairstyles by crossing through combed and stringed hair14. According to Table 1, samples SG and OB, which have a slight curve, might be the broken heads of “Chai”; samples TB and LG, which are straight sticks, appear to be parts of the hairpin body; sample OW, with a sharp end, represents the foot of a hairpin.

Scientific methods

The samples, originating from the glass assemblages, were exceptionally rare for local archaeologists. Consequently, non-invasive and micro-invasive approaches were predominantly employed for scientific studies. Techniques such as 3D digital microscopy, Laser Ablation-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS), Raman micro-spectrometry, and micro-CT were applied to the specimens. The instrument conditions and measurement parameters for each method are given below.

3D microscope

A Keyence VHX 5000 3D digital microscope was used for surface analysis. It consists of high brightness LED light source with 5700 K colour temperature, an image sensor of 1/1.8-inch, CMOS image sensor with virtual pixels of 1600 (H) × 1200 (V), and a progressive scanning system with 50 frames/sec.

LA-ICP-MS

In the past ten years, LA-ICP-MS has gradually become the most reliable micro-invasive method for analysing the chemical compositions of archaeological glasses15,16,17. In this study, LA-ICP-MS analyses were performed at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Key Laboratory for Biomedical Effects of Nanomaterials and Nanosafety at the Institute of High Energy Physics in Beijing, China. For quantitative analysis of major, minor, and trace elements, a Iridia laser ablation system (Teledyne Photon Machines, Bozeman, USA) with a 193 nm ArF excimer laser was coupled to a NexION 300D ICP-MS (PerkinElmer, Norwalk, USA) using the ARIS. Helium was used as transport gas.

For the LA-ICP-MS analysis, the ICP-MS was tuned using a NIST SRM 612 glass certified reference material to maximize 115In and minimize oxide interference (e.g., UO+/U+). The original samples were placed into the analytical drawer and the line scan mode selected. Due to the weathered sample surface, ablation was applied in two steps, with a pre-ablation time of 30 s followed by analytical time of 30 s. The laser fluency for pre-ablation was set at 3.8 J/cm2 with a laser frequency of 200 Hz for ten repetitions. Then, with regard to sample analysis, there were 6 designated lines ablated within the pre-ablated zone. The laser spot size was set at 20 μm, and the distance between lines was set as 20 μm. The laser frequency and fluency were set at 10 Hz and 1.5 J/cm2 respectively.

The chemical compositions of the samples were calculated and presented for 57 elements in quantitative weight percentage as oxides for major and minor components, and elemental ppm concentration for trace elements. The quantification was tested using a range of well-characterized glass reference materials, including Corning reference glasses and NIST SRM glasses. Microsoft Office Excel 2018 was used for data treatment and analysis. The precision and accuracy of the analysis of major and minor oxides have been evaluated through repeat analysis of Corning glass B, C and D18 and for trace elements by using NIST 610 and 61219,20. The results of these analyses are presented in Supplementary Appendix I, while relevant oxides and trace elements discussed in this paper are given in Table 2a, b. Corning C and D were used as references for lead-barium glass and high-potash glass, respectively. Averaging across ten individual analyses, the relative standard deviation (RSD) for Corning C was lower than 1% for MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, K2O, CaO, Fe2O3, CuO, and PbO. In terms of accuracy, except for SiO2 and CaO, which have accuracies of 9.5% and 9.9% respectively, the key oxides vary between 0.5% and 3.3%.

Apart from P, Cl, Cr and Se, the vast majority of NIST 610 trace elements display reliable results with accuracy varying from 0.15% to 15%. Appendix II lists the full results of LA-ICP-MS per sample, reporting major and minor elements in weight percent oxides and trace elements in ppm.

Raman microspectroscopy

Raman microspectroscopy has consistently been employed to investigate the colorants or opacifiers in archaeological glasses21,22. In this study, the samples were examined non-destructively with a HORIBA HR800 Raman microspectroscope coupled with an Olympus microscope, for surface analysis at a magnification of 50×. Raman spectra were collected using a liquid nitrogen-cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. The laser source was a 100 mW, 532 nm, frequency-doubled Nd-YAG laser. The test energy is set at 50 mw. The experimental wavenumbers ranged from 170 to 2000 cm−1.

X-ray micro computed tomography

With the development of X-ray technology, micro Computed Tomography (micro-CT) is increasingly used in the field of cultural heritage. As a non-invasive three-dimensional imaging technology, micro-CT offers high precision and three-dimensional positioning, allowing for the measurement and differentiation of samples at the micron or even nano level. This capability aligns with the demand for exploring the structure of cultural relics. The technique has been applied to study the internal structure and manufacturing processes of glass beads. Using X-ray CT technology, researchers can obtain specific and detailed information that is not visible to the naked eye, transforming more assumptions into realistic visual representations. For instance, polychrome eye beads have been examined using the X-ray CT method to investigate the intriguing manufacturing processes of ornamental glasses23,24. The micro-CT used is an YXLON CT Modular, Germany, with three scanning modes, namely RID-600, RID-MF and LDA-600. In this paper, we used the mode RID-MF. In this mode, the X-ray source is FXE 225.48 (Microfocus X-ray system) and the detector is Y.XRD 1620 (Flat Panel Detector). Given the consistent sizes of the hairpin samples, the scanning conditions were set with a voltage of 190 kV, a current of 0.33 mA, and a spatial resolution of 9 μm.

Results and discussion

Chemical characteristics of the glass pins

The chemical characteristics of the glass hairpins provide valuable insights into the raw materials and manufacturing techniques used in their production. This information is crucial for understanding the technological and cultural aspects of ancient glass-making practices. The chemical compositions were analysed and presented for 57 elements in quantitative weight percentages and ppm concentrations using LA-ICP-MS (Appendix II). The five samples could be divided into two types: four high potash high lead oxide glass (K₂O-PbO-SiO₂ glass) including samples LG, SG, OB, and OW; and high potash high lime silica glass (K₂O-CaO-SiO₂ glass) represented by sample TB.

K2O-PbO-SiO2 glass

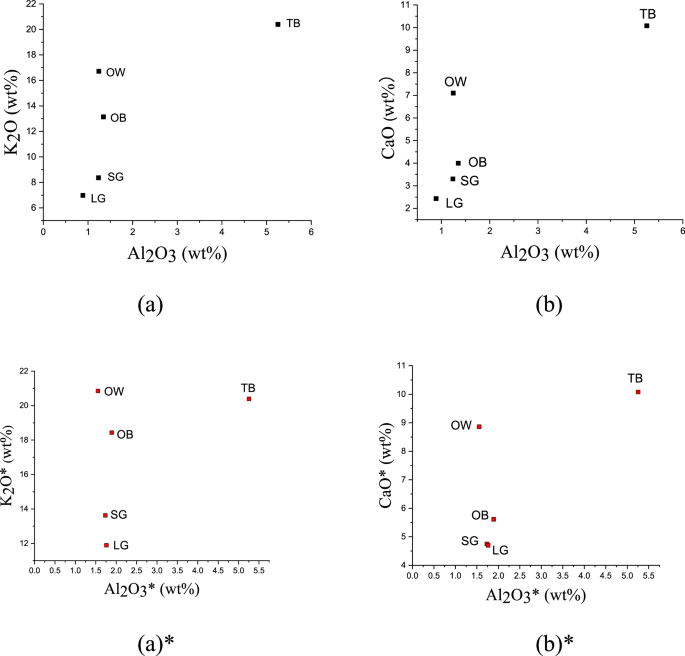

The four samples LG, SG, OB, and OW are translucent or opaque in light green, dark green, blue, and white, respectively. They are classified as K₂O-PbO-SiO₂ glass due to their considerable potash levels (ranging from 7.0 wt% to 16.7 wt%), and extremely high lead oxide content, ranging from 20 wt% to nearly 50 wt%. To explore potential sources of other elements from the four high-PbO samples we followed the concept of the ‘base glass’ developed by R. Brill25. The concentrations of lead oxide were excluded and the level of major and minor oxides, such as SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, MgO, CaO, Na2O, K2O, MnO, P2O5, TiO2, Sb2O5 and CuO, were recalculated and marked with an asterisk in Table 3 and Fig. 3. After excluding the percentages of lead oxide, the glasses are similar to potash glass with between 12 and 21 wt% K2O. Results of relevant trace elements lists in Table 4.

a Scatter plot of weight percentage of K2O versus Al2O3; b Scatter plot of weight percentage of CaO versus Al2O3; a* and b* are the scatter plots of the same oxides as a and b after excluding weight percentage of PbO from high PbO samples LG, SG, OB and OW.

According to Fig. 3b, b*, these four samples have low levels of alumina, less than 1.5 wt% in the full analyses and less than 2 wt% in the recalculated base glass, and relatively lower lime content, ranging from 2.4 wt% to 7.1 wt%, compared with those of sample TB. There is no significant difference in the plots of alumina versus lime among the five samples, with and without lead oxide. It is also worth noting that these four samples exhibit significantly low levels of soda between 0.15 wt% and 0.9 wt% free of lead oxide (Table 3), which might indicate that feldspar, a common mineral containing varying amounts of potassium, sodium and calcium alongside alumina and silica, was not involved in the glassmaking process for this high potassium high lead glass type.

The four samples show only small amounts of MgO and P2O5 even after excluding the PbO concentration, with average concentrations of 0.14 wt% and 0.08 wt%, respectively. This suggests that the flux likely came from mineral salt rather than plant ash, given that plant ash soda-lime-silica glass generally contains magnesia and potash levels above 1.5 wt%26,27, and P2O5 varying between 0.2–0.4 wt%17. Similarly, Cl concentrations in plant ash glass are typically around 1 wt%, but this group only has 0.1–0.15 wt%, indicating a mineral source.

Glass produced in China typically exhibits the characteristics of mineral-based glass raw materials28. During the Warring States period and the Han dynasty (475 BCE to 220 CE), lead-barium glass, typically produced in China, was also widely used there, and even transported from the Central Plains to Xinjiang region29,30. The use of lead-barium glass gradually declined, with high lead glass emerging during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) and lead-potassium glass between the Song and Yuan dynasties (960–1386 CE)12,31,32. Thus, these types of glass rarely show evidence of plant-based materials being involved in the glassmaking process in China, as indicated by the observation that impurity oxides associated with plant ash flux, such as MgO and K2O, are consistently present only at low levels in lead-barium glass and high lead glass, typically less than 1 wt%31. MgO in lead-potassium glass also follows this trend.

Over the past three millennia—from the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) to the Ming dynasty (1368–1544 CE)—lead oxide has consistently been a major component of raw materials used in Chinese glassmaking. Concentrations of lead oxide in lead-barium glass, high lead glass and lead-potassium glass vary from 30 wt% to 50 wt%, comparable to or even exceeding the silica content. There are probably two main reasons for adding lead oxide to the glass batch. The first reason is that lead oxide can be added as a flux to reduce the melting temperature of silica. The working range of high-lead glass typically spans between approximate 600 °C and 800 °C33. This lower melting temperature, compared to other types of glass such as soda-lime-silica glass, is due to the high lead content, which lowers the temperature required to melt the glass and decreases the fuel cost. Another reason is that lead oxide facilitates opacifying crystallite distribution evenly in the glass matrix with less precipitation34.

After the Tang dynasty, lead-potassium glass seems to be the most popular one and widely distributed in China. Several Chinese publications on scientific glass study have reported findings of glasses which are only qualitatively identified as this type of glass according to the compositional results. In central plain of China, such as Henan province, a few glass pins dated to the Jin and Yuan Period of the 12th -14th century CE were identified as K2O-PbO glass combined with K2O-CaO glass 2232. In Northeast China, Liaoning province, at the Xiao-la-ba-gou tomb site dated to the Liao Dynasty (918–1120 CE), glass ornaments decorating an iron waistband were regarded as the same type as well35. However, the use of XRF analysis without reference calibration, often conducted on weathered surfaces, produced results that cannot facilitate further comparison.

K2O-CaO-SiO2 glass

Sample TB is a broken fragment with slight weathering. According to the reflected light image of TB from Table 1, it is transparent and light blue in colour, resembling the visual effect of natural crystal. Table 3 shows that TB contains a significant amount of potash (20.4 wt%) and a very low level of soda (1.4 wt%). Thus, the flux of sample TB is unlikely from plant ash, but probably from nitre, which consists mostly of pure potassium nitrate (KNO3). Another notable feature of the sample is its lead oxide content. Unlike the four high-lead specimens, which exhibit extraordinarily high levels of lead oxide, sample TB contains only 0.35 wt%.

Compared with the high-lead group, TB contains a considerably high concentration of lime at 10.1 wt%, similar to the high-lead sample OW. Generally, calcium oxide is an essential component in glass as a network stabilizer; without it, an alkali-silica glass would tend to be dissolved by water. Similarly, high alumina levels also act as stabilizer. In this case, such a high level of calcium oxide suggests that calcium-rich additives were intentionally added as a stabilizer, alongside an alumina-rich silica source. This likely explains why TB was preserved in good condition when excavated from the muddy port site after approximate 1000 years.

It is unusual to scientifically confirm the K2O-CaO-SiO2 glass from the 10th–13th century. Sample TB is likely represents the first discovery of this distinctive glass type in southern China. So far, only one among six samples discovered at the capital city site of the Liao dynasty (10th–12th century CE) in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region6, has similar compositions to TB in terms of major and minor oxides. This glass find is a blue opaque spherical object with a still high level of potash (7.5 wt%) despite severe weathering. It also has a considerable lime content (8.1 wt%) and low lead oxide (1.2 wt%), indicating it is a K₂O-CaO-SiO₂ glass, unlike the associated five high-Pb glass samples analysed by LA-ICP-AES. However, a distinguishing feature of this object is its alumina concentration, which is only 1.5 wt%, compared to 5.3 wt% in sample TB. This suggests that different silica sources might have been used for their production, and could explain its more severe corrosion.

Published scientific studies on Chinese glasses demonstrate that during the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), most of potash glass beads were likely produced in or imported from India to the coast of Guangxi province, south of China36. In addition, glass beads found in the Qiemo cemetery sites, a major stop on the ancient southern line of the Silk Road in the Xinjiang Region, are dated to the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 24 CE). Here, a transparent glass bead with chemical characteristics of 15 wt% potash, 2.8 wt% lime, and 1.3 wt% alumina indicates that it is a type of high potash glass. This potash glass was likely imported to the Xinjiang region and was probably not made locally37.

High-potash glasses were produced simultaneously in both Eastern and Western regions. “Forest glass” is a type of late medieval glass produced in northwestern and central Europe from approximately 1000 CE to 1700 CE using wood ash, characterized by potash (10–20 wt%) and magnesia (5–10 wt%)25,38. This composition is quite distinct from the K₂O-CaO-SiO₂ glass with minimal magnesia found in the samples studied. It is less likely that this glass was recycled from earlier materials or imported from Europe. It is intriguing to note that high-potash glasses were being produced contemporaneously in both the East and the West, though with different raw materials utilized in each region.

A type of high alumina mineral glass was firstly analysed by Brill39, then Dussubieux studied and discovered this type of glass compositions in various colours from South Asia and Southeast Asia40. The significant features of this glass are the high alumina content, usually above 6 wt%, and low magnesia, around 1 wt% for blue glass. In South and Southeast Asia, an efflorescent salt found on the plain south of the Ganges, called “reh” was used for glassmaking. Combined with a sand source rich in alumina, the soda glass was present from the earliest to the latest sites, with possible many primary production sites spread. In terms of K₂O-CaO-SiO₂ glass, the potash is assumed to originate mainly from nitre which can be found in arid regions, often in the form of white crystalline efflorescent deposits, similar to the formation of reh in India. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the manufacture of K₂O-CaO-SiO₂ glass in the Song dynasty may have been influenced by Indian mineral soda-lime-silica glass-making traditions, and adapting them to the locally available raw materials.

Trace elements analysis

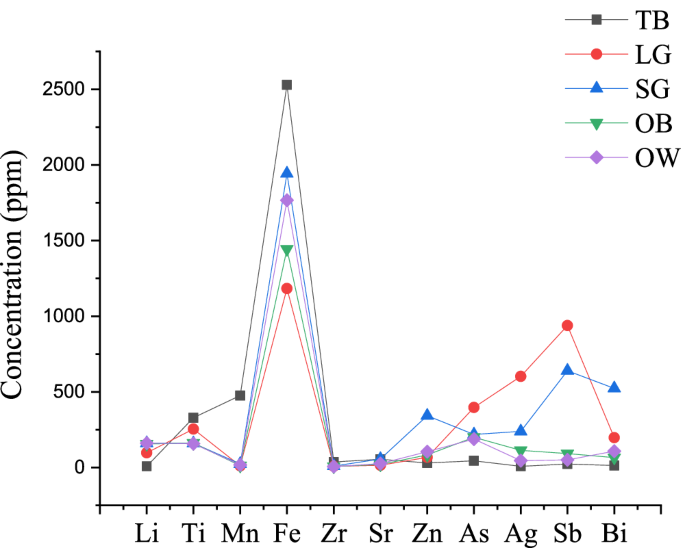

Among the five samples, there are compositional discrepancies not only in major elements but also in some minor and trace elements which were introduced into the glass batches as part of the raw materials. In characterizing these groups, a distinction can be made between elements most closely associated with the silica source, such as Li, Ti, Fe, and Zr39,41, and those related to lead and copper minerals, including As, Ag, Sb, and Bi among the four high-lead samples27,42.

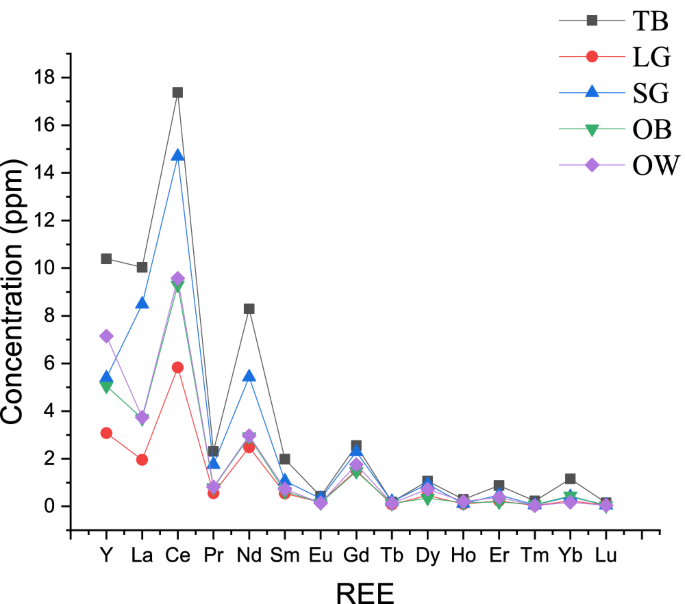

The trace element patterns highlight differences between the samples. Concentrations of trace elements in the five samples are illustrated in Fig. 4. The concentrations of elements Li, Ti, Fe, and Zr in the four K2O-PbO-SiO2 glasses are similar to each other but distinct from those in sample TB, which is consistent with the results of rare-earth elements (REE) analysis in Fig. 5. Rare-earth element concentrations reflect the geological signature of rock units, including pebbles and sands, and indicate the general rock type43. Thus, potential variations in silica sources suggest different origins between TB and the other four samples.

Correlation curves of the trace elements of the five samples. Correlation curve of the trace elements Li, Ti, Mn, Fe, Zr and Sr of the five samples relevant to silica sources, and Zn, As, Ag, Sb and Bi relevant to lead sources. Note the different profile of silica-related elements for TB, and the separation of the lead-related elements into two groups, LG & SG and OB & OW, respectively.

Note the different pattern for sample TB compared to the other four glasses.

Regarding the contents of Zn, As, Ag, Sb, and Bi among the four high-lead samples, Fig. 4 illustrates that OB and OW exhibit a similar pattern, which is distinct from the pattern of LG and SG individually. This suggests the possibility of two different lead sources for these four samples. However, it does not conclusively demonstrate that the four high-lead samples were produced in different locations or workshops in China. Due to the constraints of non-invasive scientific analysis, lead-isotope analysis could not be conducted to pinpoint the specific origins of lead in the glasses.

Relationship with the archaeological site

Various kinds of vitreous finds have been excavated in China, dating from the Western Zhou dynasty (11th to 8th century BCE) to the Ming dynasty (14th to 17th century CE)29. However, the earliest and only glass furnace site discovered in Yanshanzhen County, Shandong Province, dates to the early 14th century, which is later than the period of the Shuo Gate port site. Evidence, including glass furnaces, crucibles, raw materials, frits, and ornamental products such as hairpins, beads, and bangles, suggests the presence of a mature glass workshop with a significant output of products. Semi-quantitative analysis by XRF indicates that the samples are predominantly of the K2O-CaO-SiO2 type, with a low lead oxide content, similar to characteristics of the sample TB from the port site44. Yanshanzhen County was a home of a glass making and working industry that may have established its tradition much earlier than the 14th century. However, there is no conclusive evidence that the glass hairpin TB was related to Yanshanzhen glass.

According to the latest archaeological bulletin10, not only were city walls, roads, piers, and three waterlogged shipwrecks excavated at the port site, but also several tons of celadon remains, with approximately 90% of the fragments coming from the Longquan celadon kiln, located less than 200 kilometres from the port site. Thus, archaeologists have accepted that the site used to be the starting point for exporting Longquan commodities to the world via the Maritime Silk Road.

Generally, hair accessories were found as part of funerary suits of the deceased. However, the assemblage discovered at the port site, comprising five different colours and opacifications, suggests that many more glass hairpin commodities, similar to these finds, were transferred into or out of ancient Wenzhou City through the port. These glass pins could be identified as commodities rather than personal belongings. During the Southern Song dynasties, the current Zhejiang province used to be a political and economic core of south China, which succeeded the Northern Song dynasty after the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty conquered the northern capital of Kaifeng, forcing the Song court to relocate south of the Huai River, with Hangzhou city (then known as Lin’an) becoming the new capital. Therefore, Zhejiang developed mature manufacturing industries in ceramics, silk, textiles, lacquers45, and possibly glass ornaments. One hypothesis is that these ornaments were produced in local workshops near Shuo Gate port and exported to other regions of China or even abroad, as suggested by a glass assemblage excavated from Shipwreck No. I in the South China Sea (1127–1279 CE). The shipwreck contained a major cargo of ceramics, including a significant amount of Longquan celadon. Among the glass artifacts, only one blue opaque fragment was analysed and identified as the K2O-PbO-SiO2 type12.

The scientific analysis of glass hairpins remains challenging for pinpointing their provenance, largely because there is still a scarcity of discovered glass workshops and related artefacts. Additionally, the limited amount of reliable scientific analysis that has been conducted makes it difficult to establish meaningful comparisons. According to published papers, both of K2O-PbO-SiO2 and K2O-CaO-SiO2 glass ornaments, excavated from the site of Shang-jing, capital city of the Liao Dynasty6 (Inner Mongolia, North of China, 907–1125 CE), and a K2O-PbO-SiO2 glass fragment from the Nanhai No. I shipwreck of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279 CE)12, were found to have fluorite as opacifier. These findings are from a similar period as this port site, which demonstrates that those two types of glass were widely distributed across a broad geographic scope from the south to the north of China.

It was generally believed that K2O-CaO-SiO2 glass and K2O-PbO-SiO2 glass did not coexist in the Song dynasty because the high-potash glass appeared much earlier than the high-lead glass31,46. However, this study shows that the two types of glass could have been produced simultaneously. The case of the same situation was found from the capital city of the Liao Dynasty, where scientific studies identified the existence of the same two types of glass. Thus, it is confirmed that high-potash glass did not fade out in China but developed alongside high-lead glass, evolving from lead-barium to lead-potassium type.

Colorants and opacifiers

As a hair decoration, the visual effect was one of the most important elements of a hairpin in terms of economic value. The five samples were selected for their representative appearances. The colouring and opacifying methods will be discussed in groups: OB & OW, LG & SG, and TB, based on the results of chemical compositions and Raman spectrometry analysis.

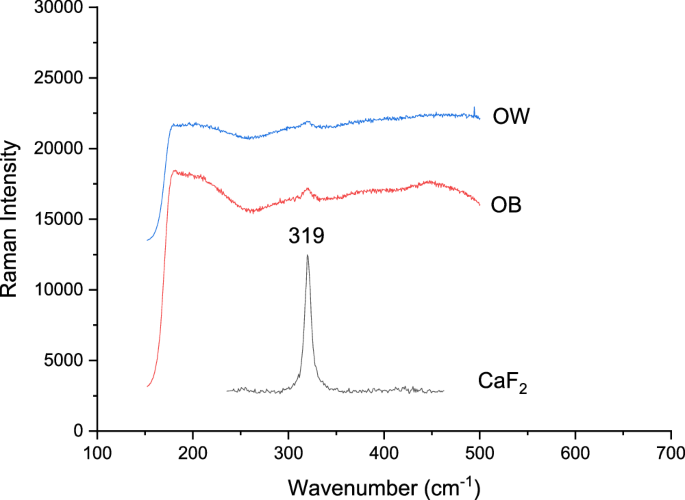

OB and OW

Among the assemblage of archaeological finds, thirteen of the seventeen pieces are blue opaque. As a representative sample, OB has 1.6 wt% copper oxide resulting in the turquoise blue colour. In contrast, the white opaque sample OW only contains much less copper oxide, 0.08 wt%. However, in order to produce an opaque glass, it was necessary to introduce a dispersion of particles within the glass matrix which can block the visible light through the material. By applying Raman spectroscopy analysis on the five sample, the absorption peaks at 319 cm−1 in the Raman spectrum of glass illustrate the existence of fluorite crystallites in samples OB and OW (Fig. 6). Probably fluorite was deliberately added into glass batch and then fluorite dendrites were formed as opacifier when fired at around 1000–1050 °C, according to the replication experiments of glass12. The dendrites result in the white opaque glass as sample OW, and to make the blue opaque glass combined with copper colorant like sample OB.

Raman spectrum graphs of the samples OB and OW, illustrating the presence of CaF2 at wavenumber 319 cm−1, compared with that of the pure mineral fluorite, calcium fluoride. From KnowItAll Raman spectral database47.

Although the fluorescence effect on samples leads to very weak Raman peaks, it is common to find fluorite in Chinese high-lead glass. Three possible fluorine minerals could have been sourced from natural occurrences: cryolite (Na3AlF6), fluorite (CaF2), and fluorapatite (Ca5F(PO4)3)12. However, according to the compositional results, samples OB and OW are characterized by low contents of Al2O3 and Na2O, and a significant lack of P2O5. Therefore, it is likely that these glasses were opacified with fluorite as the most common source of fluorine. This suggests a traditional technique for opaque glasses that imitate the visual effects as jade.

LG and SG

The samples LG and SG, of translucent light green and opaque dark green colour, contain copper oxide at 0.86 wt% and 1.35 wt%, respectively, which in lead glass contributes to the green colour of the glass. Moreover, level of Fe2O3 between 0.41 wt% and 0.56 wt% is quite similar to that of the white sample OW with 0.51 wt%, which seems that iron in low concentration is not the colorant factor of the high lead glass. Although no specific opacifiers could be identified around the surface and fracture section by Raman spectroscopy, probably due to the high-lead compositions and deteriorated surface, it is still likely that opacifiers had been applied in both of the glasses.

TB

As the only transparent blue fragment, TB is a unique sample among the assemblage of glass finds. TB contains 0.91 wt% CuO, which displays a pure transparent blue colour without interference from impurities such as iron. Notably, TB is characterized by the highest levels of iron and manganese, with 2529 ppm and 476 ppm respectively, while the other samples range from 1183 to 1943 ppm for iron and 11 to 24 ppm for manganese. It is unlikely that manganese was intentionally added by craftsmen but it may neutralize the colour effects of the iron as a clarifying agent in the TB glass.

Manufactures of the glass pins

Many archaeological finds have given us the impression of integral hairpins, which can be roughly divided into three parts: head, body and foot. The head part is always held by hand when it is inserted into the hair. The foot part is sharp and nail-shaped to smoothly secure the hairstyle. The section between the head and foot is regarded as the hairpin body. Typically, the body shows a slight tapering from top to bottom in terms of thickness. The top side is relatively thicker and gradually becomes slimmer along the body.

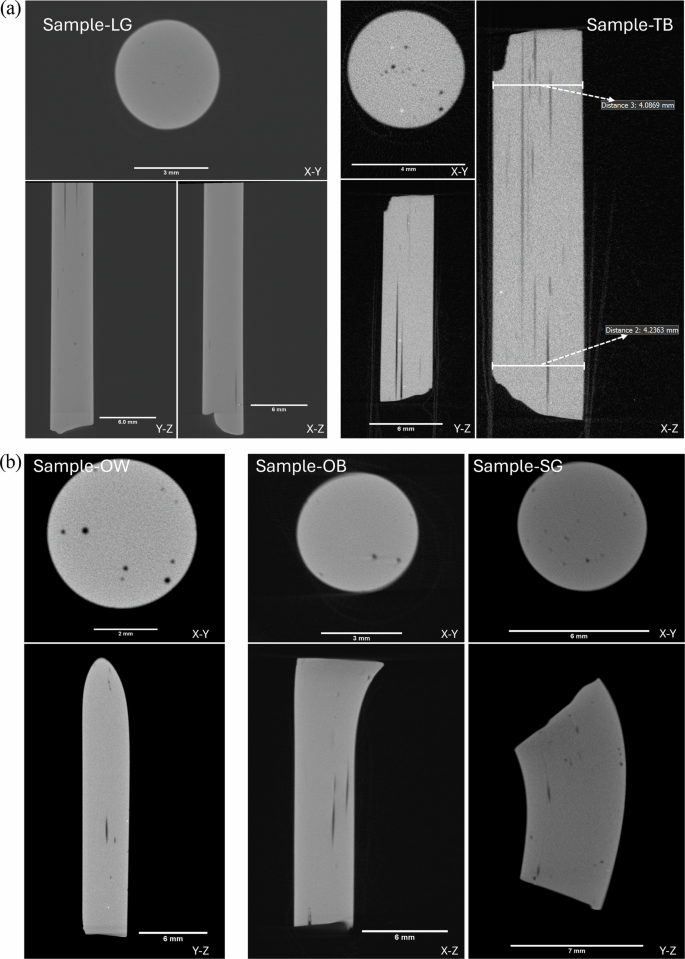

The different grey levels in the CT images display materials with different densities. Using the filtered back projection (FBP) algorithm, the geometric structure and interior information of the samples can be determined. Based on the shapes of the fragments, they can be classified into three groups: body for samples LG and TB, head part for samples OB and SG, and only sample OW with a nail-shaped foot.

Figure 7a illustrates the cross-sectional and longitudinal micro-CT images of sample LG, shown in grey. The sample is composed of homogeneous and dense glass with several small holes. These holes, shown in black, indicate the presence of deformed air bubbles within the glass stick. In the cross-sectional image, the bubbles appear as regular round shapes, while in the longitudinal image, they appear as extremely long and slender outlines. This demonstrates that the molten glass was stretched into long and thin sticks in hairpin moulds before or during the annealing procedure. A similar situation was observed in the case of sample TB. Several long and narrow holes are also clearly observed in the longitudinal image. Notably, the difference between the head and foot side of the broken stick, e.g. in sample TB, can be accurately judged by high-resolution scanning. The head end is relatively thicker, with a diameter of 4.24 mm, while the foot end is thinner, with a diameter of 4.09 mm.

a Sample LG and TB; b Sample OW, OB and SG.

Samples OB and SG are regarded as the head parts of hairpins due to the slight bend in their curved lines. It is possible that they were originally the head parts of single-foot hairpins with a curved design or the head parts of “U-shaped” hairpins with double feet. The CT results show that both samples are composed of homogeneous and dense glass with a few deformed air bubbles in a slender oval shape. It is intriguing to observe that the image of sample SG (Fig. 7b) displays two long bubbles following the curve of the head, suggesting that the glass was initially stretched while in a melted state and the bending occurred afterward. However, the bending side is much thicker than the other side, reflecting the skilled craftsmanship involved in shaping and carfting of this hairpin.

Sample OW is a fragment of a hairpin with a sharp tip. The cross sections of pores at the top of the tip are round, while the longitudinal section of them is oval. The bubbles within the tip area form bent lines along the sharp end (Fig. 7b), indicating that the sharp foot was likely formed in a specific mould during the hot melting process rather than through cold polishing treatment after annealing.

Based on observations from micro-CT images, the glass hairpin manufacturing process can be inferred to involve two main steps. First, molten glass is stretched into long sticks and cut into similar lengths and thicknesses. In the second step, a short glass stick is reheated, and the thick flow is stretched and modified according to the principle of ‘fat head and thin foot.’ For ‘U’-shaped hairpins, a longer glass rod is reheated and bent into various designs as desired by the craftsmen. Variations in thickness, length, and shape may reflect skilled craftsmanship, aimed at achieving specific aesthetic or functional qualities in each piece.

Conclusions

Few studies so far have focused on glass ornaments from the Chinese Song dynasty. Here, scientific research using multi-disciplinary methods has determined the embedded characteristics of chemical composition and manufacturing information of the glass hairpins excavated from the ancient Shuo Gate port. The hairpins are divided into two types based on their compositions: high potash high lead oxide glass (K₂O-PbO-SiO₂ glass) and high potash high lime silica glass (K₂O-CaO-SiO₂ glass). These types seem to reflect the origins of Chinese glassmaking. The K₂O-CaO-SiO₂ glass type may have been influenced by Indian mineral soda-lime-silica glass, while the K₂O-PbO-SiO₂ glass type was inherited and modified from the traditional lead-barium glass of the Han dynasty and high-lead glass of the Tang dynasty, spanning the first millennium BCE to the first millennium CE. The levels of major elements show the distinct provenances of the two types, and the representative trace elements possibly indicate two lead sources for the K₂O-PbO-SiO₂ glass samples. Crystalline fluorite was detected in the white and blue opaque glass pins by applying Raman spectroscopy. Additionally, stretching during the glass working process was observed through micro-CT, which provides us with specific information on manufacturing techniques.

It is noteworthy that glass ornaments in five different colours and opacifications were discovered from the location of a port site. This probably suggests that they were likely commodities, rather than funerary items usually found in tomb sites. Combined with archaeological discoveries including numerous Longquan ceramics, three shipwrecks, and architectural remains at the port site, these ornaments were possibly produced in regional workshops near Shuo Gate port and exported to other regions of China or even abroad. It has been discovered that these two types of glass were widely distributed across a vast geographic area from southern to northern China, even with a shipwreck yielding K2O-PbO-SiO2 type of glass ornaments. If more glass working sites are to be discovered and more quantitatively scientific analyses on glass finds are carried out in the future, it will contribute to a deeper understanding of the origins of Chinese glass, its trade and communication with the world along the Maritime Silk Road.

Responses