Chiral Floquet engineering on topological fermions in chiral crystals

Introduction

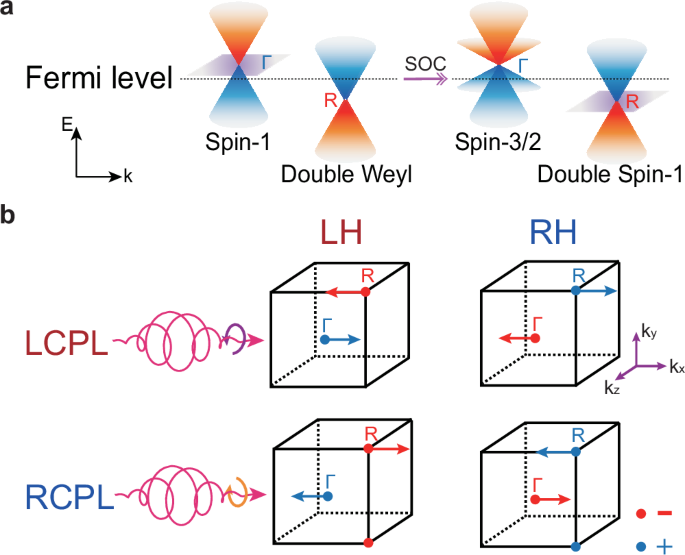

Chirality, which refers to the misalignment between an object and its mirror image, is a prevalent phenomenon in the natural world1,2,3,4. In the realm of a quantum material, constrained by chiral space groups (SGs)5, chiral crystals exhibit a distinct handedness η in their lattices due to the absence of mirror, inversion, or roto-inversion symmetries5,6,7. For example, within the chiral SG 198 (P213), the compound family of CoSi hosts left-handed (LH, η = + 1) and right-handed (RH, η = − 1) lattice structures8,9, which are mirror images of each other. Due to the protection of the chiral crystal symmetry, the CoSi family possesses unconventional chiral fermions with higher topological charges in bulk states8. Namely, in the LH CoSi without spin-orbit coupling (SOC), spin-1 excitation and double Weyl fermion with topological charges + 2 and − 2 emerge at Γ and R points around the Fermi level, characterized by the fermion’s chirality (defined by the sign of the topological charge10) χΓ(η) = + 1 and χR(η) = − 1. Upon inclusion of SOC, the chiral fermions at Γ and R points become spin-3/2 and double spin-1 fermions11,12, as shown in Fig. 1a. These chiral topological fermions have led to many chirality-dependent intriguing physical phenomena in chiral crystals, a field that has garnered much attention over the past few years. These phenomena include helicoid surface states6,13,14,15,16,17, circular photogalvanic effect18,19,20,21, chirality locking charge density wave7, the interference of chiral quasiparticle22,23, and other attributes such as unconventional resistivity scaling24, orbital transport25, exotic excited modes26,27 and quasi-symmetry-protected topology28.

a A schema of topological fermions at Γ and R points which exhibit spin-1 (spin-3/2) and double Weyl (double spin-1) excitations without (with) SOC around the Fermi level in CoSi. b Schema of the left-circularly polarized light (LCPL)- and right-CPL (RCPL)- induced momentum shifts for topological fermions, marked as blue and red arrows, in the LH and RH CoSi crystal via Floquet engineering. The black cube represents the Brillouin zone (BZ) of the CoSi family and the red negative and blue positive signs denote the sign of topological charges.

Photon, like various chiral quasiparticles, possesses an optical chirality γ, referring to the left- and right-circularly polarized light (LCPL, γ = + 1 and RCPL, γ = − 1). Leveraging time-periodic laser fields, Floquet engineering emerges as a potent avenue to realize light-dressed states through virtual-photon absorption or emission processes, thereby enabling an opportunity to engineer electronic structures and topological properties of quantum materials in non-equilibrium29,30,31,32,33. Especially, with CPL pumping, the time-reversal symmetry (TRS) in the host material is transiently broken, inducing many interesting phenomena that have been observed experimentally, including the dynamical gap opening of Dirac cone on the surface state of topological insulator34,35, as well as CPL-induced anomalous Hall conductance in graphene36,37 and Cd3As238. Theoretically, CPL-driven Floquet engineering is proposed in many topological systems, encompassing the momentum shift of chiral Weyl nodes39, the splitting of Dirac fermions40,41, and the driving of topological phase transitions in semiconductors42,43,44,45,46,47 and semimetals48,49,50,51,52,53,54. While the exploration of the interplay between the chiralities of light and chiral crystals is still lacked, which can provide a new chance to manipulate electronic properties of chiral topological materials.

In this Letter, we report the chiral Floquet engineering on topological fermions in the CoSi family using the Floquet effective k ⋅ p model from the perturbation theory, complemented by the Floquet tight-binding Hamiltonian based on the ab initio calculations as a benchmark. We show that under CPL pumping, gapless topological fermions with different topological charges undergo momentum shifts along opposite directions (see Fig. 1b) while preserving their topological properties. This phenomenon is distinct from the momentum shifts of Weyl points driven by the light-induced shear phonon mode in WTe255 and shifts of topological fermions under the linearly polarized light (LPL)56,57. The sign and magnitude for light-induced momentum shifts at Γ and R points are determined by the Floquet chirality index Ξk=Γ,R, which depends on the light-matter coupling strength and the interplay among the three distinct chiralities, the crystal handedness η, the chirality χk=Γ,R(η) of topological fermions, and the chirality γ of CPL. Via analyzing the Lie algebra representations of ({mathfrak{su}}(2)) for effective Hamiltonians of topological fermions under laser pumping, we provide a comprehensive understanding of chiral Floquet-engineered transient change of electronic structures in CoSi, which could be detected by the Mid-IR pumping and THz Kerr or Faraday probe spectroscopy measurements in an ultrafast time scale58.

Results

k ⋅ p model analysis

We start from the effective k ⋅ p model to investigate the evolution of topological fermions in the LH CoSi (η = + 1) under CPL pumping in the framework of the Floquet engineering. For the CoSi compound, electronic structure calculations without SOC reproduce experimental observations faultlessly6,14,15,16, thus in the following we focus on CoSi and do not include the SOC effect (see the Supplementary Note 1). For compounds composed of heavy elements such as AlPt13 and PdGa17,23, SOC must be considered seriously and related discussions are shown in Supplementary Note 2 and Note 4. At the Γ point, the topological fermion around the Fermi level in the CoSi compound is represented as a spin-1 excitation with χΓ(η) = + 18 and its k ⋅ p Hamiltonian is ({hat{H}}_{Gamma }({bf{k}})=hslash {v}_{Gamma }eta {bf{k}}cdot {bf{J}}), where ℏ is the reduced Plank constant, vΓ > 0 denotes the Fermi velocity for spin-1 excitation, k is the momentum and J = (Jx, Jy, Jz) represents the matrix representation of the spin-1 angular momentum operator.

Given that CoSi is a non-magnetic material with TRS but lacks inversion symmetry due to its chiral crystal structure, the light-matter interaction will yield distinct phenomena depending on the type of pumping laser used. The LPL can indeed break the inversion symmetry of the material, however, in the case of the chiral crystal CoSi, unlike the previous study on the organic salt with tilted Dirac nodes56, LPL does not introduce any new changes of symmetry (see the Supplementary Note 3 and Note 4). On the other hand, CPL can break the TRS of CoSi, potentially leading to the emergence of transient anomalous Hall signals39. Consequently, we focus exclusively on the CPL in our study. We consider the CPL to be incident along the x direction with a frequency Ω and a vector potential ({bf{A}}(t)={A}_{0}(0,gamma sin Omega t,cos Omega t)) where A0 is its amplitude. Then we apply the Peierls substitution to account for the light-matter interaction term and the Floquet theory with the Magnus expansion59 to calculate the light-dressed electronic structures for spin-1 excitation, whose Floquet effective k ⋅ p Hamiltonian is obtained as (see the Supplementary Note 2)

Herein, we redefine A = eA0/ℏ as the effective amplitude of the vector potential for simplicity, in which e is the charge of the electron. As calculated results illustrated in Fig. 2a, it is evident that the spin-1 excitation with threefold degeneracy in the LH CoSi keeps its gapless nature under the irradiation of the CPL, without the change of its topological charge. Instead, the crossing point shifts along the x direction in momentum space with the magnitude of δΓ, which is given by

Here, we propose the quantity of ({Xi }_{Gamma }=frac{gamma {chi }_{Gamma }(eta ){A}^{2}}{Omega }) as the Floquet chirality index for the first time, which combines the chirality γ of CPL and χΓ(η) of topological fermion and also depends on the crystal handedness η. The interplay among these chiralities via Floquet engineering determines the light-induced momentum shifts of spin-1 excitation in CoSi.

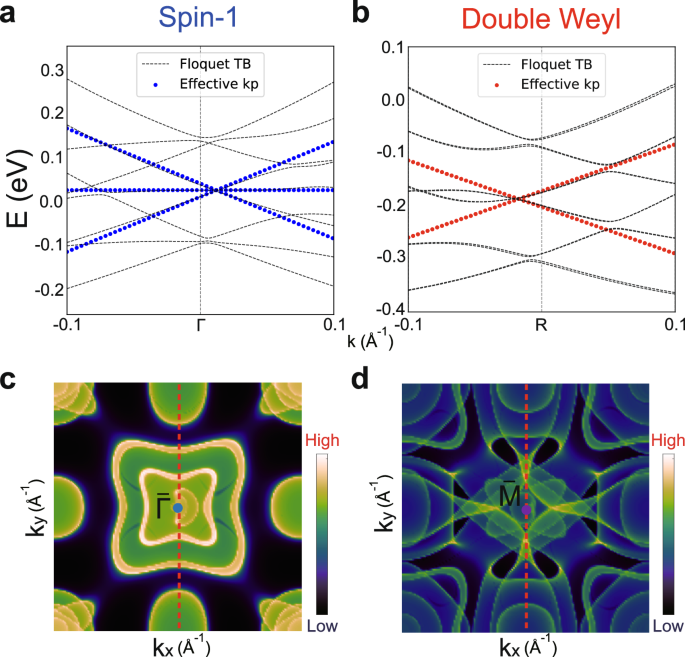

a, b The Floquet band structures around Γ and R points for the LH CoSi under the radiation of the LCPL without SOC. Blue and red dot lines in (a) and (b) are obtained from the Floquet effective k ⋅ p model and the black dashed lines are obtained from the diagonalization of the Floquet tight-binding Hamiltonian. The cut-off of the Floquet index is set as n = { − 1, 0, 1}, and the Fermi levels are set as zero. In these calculations, the photon energy is 100 meV and the electric field intensity is 4.4 × 107 V/m. c, d The projection of the bulk states around Γ and R points onto the (001) side surface respectively, where (bar{Gamma }) and (bar{{rm{M}}}) points are their projected points. The energy levels in (c) and (d) are set at crossing points of the spin-1 excitation and double Weyl fermion, respectively.

For the double Weyl fermion at the R point with opposite topological charge [χR(η) = − 1], we can demonstrate that its crossing point shifts to an opposite direction in momentum space under the same laser driving, in contrast to the evolution of the spin-1 excitation at the Γ point. The effective k ⋅ p Hamiltonian of the double Weyl fermion can be expressed as a direct sum of two decoupled Weyl fermions as ({hat{H}}_{{rm{R}}}({bf{k}})=hslash {v}_{{rm{R}}}eta {bf{k}}cdot ({boldsymbol{sigma }}oplus {boldsymbol{sigma }})), where vR > 0 represents the Fermi velocity at the R point and σ = (σx, σy, σz) are Pauli matrices. In the same way, we obtain the Floquet effective k ⋅ p Hamiltonian ({hat{H}}_{{rm{R}}}^{eff}({bf{k}})) as (see the Supplementary Note 2)

and the shift δR expresses as

which is opposite compared to the light-induced momentum shift of the spin-1 excitation, as shown in Fig. 2b with red dot lines for LCPL (γ = + 1).

Intriguingly, a similar effect of momentum shift is reported for the Weyl fermion upon exposure to CPL39. We can take it as an example to understand such an effect for topological fermions in the framework of Lie algebra. The Pauli matrix σ appearing in the effective Hamiltonian of Weyl fermion (({hat{H}}_{W} sim {boldsymbol{k}}cdot {boldsymbol{sigma }})) is the generator of the Lie algebra ({mathfrak{su}}(2)). Because of the completeness of the two-dimensional Pauli matrix, the correction term from the Floquet commutator within the Magnus expansion (see the Supplementary Note 2) still can be expressed by the Pauli matrix σ. Thus, under the CPL pumping, there will be a light-induced momentum shift for the gapless Weyl fermion. Such result is in sharp contrast to the dynamic behavior of the Dirac fermion [({hat{H}}_{D} sim {bf{k}}cdot ({boldsymbol{sigma }}oplus {{boldsymbol{sigma }}}^{* }))] under the Floquet engineering, which will be converted to a pair of Weyl fermions with opposite chirality40. We can also understand this phenomenon in the framework of Lie algebra. Because σ ⊕ σ* is not the generator of ({mathfrak{su}}(2)), ultimately the Dirac fermion will undergo a photoinduced momentum splitting and lead to the emergency of Floquet-Weyl cones under CPL radiation (see the Supplementary Note 3).

Within the similar analysis, we found that, for spin-1 and double Weyl fermions, both J and σ ⊕ σ can serve as generators of the Lie algebra ({mathfrak{su}}(2)). We can prove that their generators can still expand the Floquet commutator (see the Supplementary Note 3). Consequently, the Floquet engineering of spin-1 and double Weyl fermions under CPL pumping resembles a similar behavior for Weyl fermions under the same condition. More generally, for the spin-S topological excitation, as long as S is the generator in the (2S+1)-dimensional irreducible representation of ({mathfrak{su}}(2)), the crossing point for the Hamiltonian (hat{H} sim {bf{k}}cdot {bf{S}}) will not be gapped under the CPL pumping in the framework of the Floquet engineering, instead, the crossing point will be shifted in momentum space. When we consider the CoSi family compounds with SOC, a spin-3/2 fermion (k ⋅ S3/2) locates at the Γ point and a double spin-1 fermion (k ⋅ J ⊕ k ⋅ J) can be found at the R point around the Fermi level. Since S3/2 and J denote generators in the 4− and 3−dimensional irreducible representations of ({mathfrak{su}}(2)), light-induced momentum shifts rather than the gap opening occur at crossing points around the Fermi level, and such analysis is consistent with our calculations based on the Floquet effective model (see the Supplementary Note 2).

Tight-binding Hamiltonian analysis

The discussion shown above is based on perturbation theory and effective k ⋅ p model that is only valid for high-frequency limit and low energy approximation31,59. To verify the robustness of the phenomena reported here, we apply the Floquet tight-binding calculations for the LH CoSi (see Methods, the Supplementary Note 4 and Note 5) in which the hopping parameters are obtained from ab initio calculations. We neglect the influence of dipole transitions, as they do not fundamentally alter the qualitative behavior of the momentum shift in our case, which is supported by previous research on the Dirac semimetal Na3Bi40. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, the light-induced momentum shifts can be observed for the gapless topological fermions at Γ and R points, which are consistent with results of the Floquet effective k ⋅ p model. Furthermore, we calculate the distributions of bulk states in the BZ for CoSi under CPL pumping when the energy levels cross the gapless points of spin-1 excitation and double Weyl fermion. The results obtained from the tight-binding calculations are shown in Fig. 2c, d, which are summed over bulk states along the kz direction and projected on the (001) side surface. Notably, in sharp contrast to the symmetric distribution of bulk states without laser pumping, the light-induced asymmetric feature can be observed in the center of plots (see regions around (bar{Gamma }) in Fig. 2c and (bar{{rm{M}}}) in Fig. 2d), attributed to TRS breaking caused by CPL pumping.

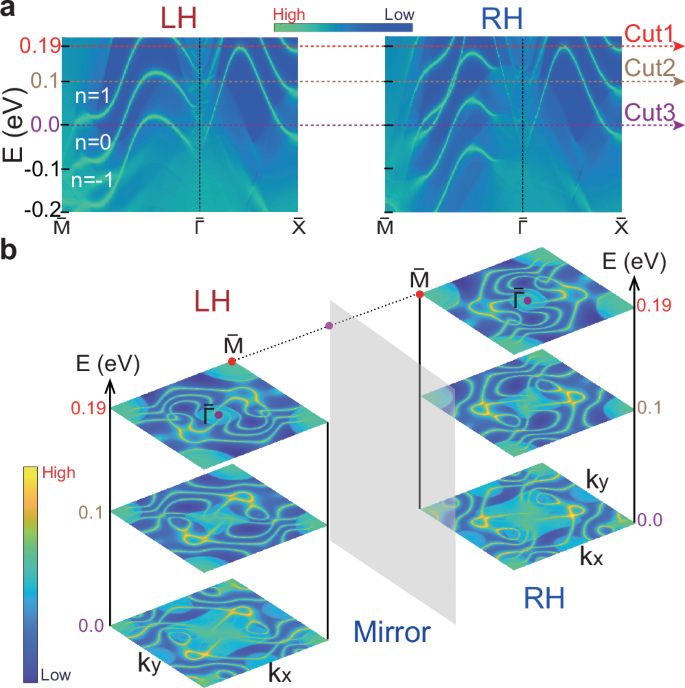

In equilibrium, the non-trivial topology of bulk states results in the emergence of Fermi arcs on the surface, which connect the projected topological fermions with opposite topological charges. So it is natural to explore the evolution of non-equilibrium surface states upon laser pumping. Here upon the LCPL pumping, we calculate the surface band structure projected onto the (001) surface for both LH and RH CoSi, as shown in Fig. 3a. Besides Fermi arcs with the Floquet index n = 0 which connect the projections of the spin-1 excitation around the (bar{Gamma }) point and the double Weyl fermion around the (bar{{rm{M}}}) point, additional replica surface states with Floquet indices of n = ± 1 also can be observed and the energy difference between the neighboring Floquet sidebands equals the pumping photon energy ℏΩ.

a The surface Floquet electronic structures along high symmetry lines, which are projected to the (001) surface for the LH (left panel) and RH (right panel) CoSi without SOC under the LCPL radiation. b The evolution of the constant-energy contours for Floquet surface states in the LH (left panel) and RH (right panel) CoSi without SOC. Three energy cuts are marked in (a) and the mirror plane is a gray parallelogram.

Figure 3 a shows the Fermi arc contours on the (001) surface for LH and RH CoSi with different energy levels. Similar to the case in equilibrium8, under laser pumping, the Fermi arcs are observed in a large energy window across the whole BZ of the side surface, which connect the projections of bulk states around (bar{Gamma }) and (bar{{rm{M}}}) points. Because the LH and RH structures in CoSi are mirror images of each other, correspondingly on the same (001) side surface, the Fermi arcs in LH and RH structures can be converted to each other via the operation of mirror symmetry (see Fig. 3b). Moreover, except for the emergency of additional replica Floquet surface states, the distribution of Floquet Fermi arcs is similar to the case without laser pumping (see the Supplementary Note 1). Upon considering the influence of SOC in CoSi and AlPt, as illustrated in Supplementary Note 4, the degeneracy of surface states is lifted while the connection of the surface states remains consistent with the scenario in the absence of SOC. Such fact indicates that upon the CPL pumping, topological properties of topological fermions in the CoSi family will not be altered although the Floquet states emerge and crossing-point positions are shifted by the pumping laser.

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrate a chiral Floquet engineering of topological fermions in the CoSi family. However, the experimental realization of Floquet engineering is still challenging and only limited to a few material candidates34,35,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67. One significant obstacle in the formation of Floquet states lies in the competition between the laser pumping and the decoherent scattering for the excited electrons68. To avoid the Floquet state’s collapse, the pumping laser period (T = 2π/Ω) should be shorter than the experimental scattering time. For a metallic system, such as the surface state of Bi2Te3, a previous study has shown that the emergency of Floquet-Bloch sidebands can be built up within a few ultrashort optical cycles35. Based on the transport measurement69, the scattering time in the CoSi single crystal is estimated as around 131 fs (see the Supplementary Note 6), which provides a lower limit to the pumping laser frequency. Consequently, considering these constraints, we expect a Mid-IR pumping laser with photon energy around 100 meV and an electric field intensity as large as 4.4 × 107 V/m can be used to excite the Floquet states in CoSi compounds. Additionally, time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TrARPES) is a powerful and direct experimental technique70 to observe Floquet band structures, such as the detection of Dirac surface34,35 and bulk66,67 states under the Mid-IR laser pumping (see the Supplementary Note 7 for details). It should be noted that a tunable probe photon energy is essential for the detection process14,16, particularly to track the evolution of topological fermions along the kz direction when subjected to the Mid-IR laser pumping that propagates along the z direction. Therefore, we propose that TrARPES can be used to probe the light-dressed electronic structures of both bulk and surface states.

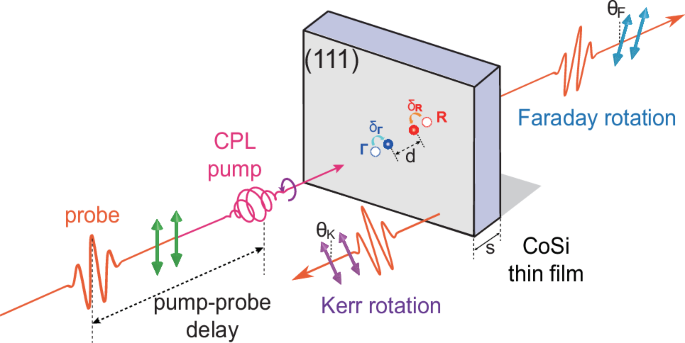

Beyond the direct observation of light-induced Floquet states, we suggest that Mid-IR pumping and THz Kerr or Faraday probe spectroscopy experiments could also be employed to probe the chiral Floquet-engineered electronic structures58. In the absence of laser pumping, no signal can be detected in non-magnetic CoSi due to the presence of TRS71. However, upon the pumping of CPL to break TRS, in general, both the non-equilibrium electron occupation and the light-induced Berry curvature can contribute to anomalous Hall conductivity (AHC). Based on the previous study in a similar setup58, we anticipate that the light-induced Berry curvature, which appears in an ultrafast time scale proportional to ∑k∈{Γ, R}χk(η) ⋅ δk39,72, could partially contribute to the AHC38,58,73 (see the Supplementary Note 7 for more detailed analysis). Given that the Kerr and Faraday angles are linearly proportional to the AHC74, we expect that the pump-probe Kerr or Faraday experiments could detect momentum shifts of topological fermions. As proposed in Fig. 4, when we apply the CPL pumping laser on the CoSi thin film with (111) surface, a finite value for Kerr angle θK and Faraday angle θF should be detected in the duration of the pumping laser.

The CPL (pink) is illuminated onto the CoSi thin film. The polarization directions of the reflected and transmitted light are denoted as purple and blue arrows, and the Kerr (θK) and Faraday (θF) angles of the linearly polarized probe pulse (orange) are measured as a function of pump-probe delay time.

In summary, applying chiral Floquet engineering on chiral crystals, we demonstrate that the CPL pumping can induce momentum shifts of topological fermions in CoSi and these shifts occur either parallel or antiparallel to the propagation direction of the incident beam depending on the Floquet chirality index Ξk. Via an analysis of the Lie algebra representation of ({mathfrak{su}}(2)) for the low-energy Hamiltonians of topological fermions, we could extend our conclusion to other SOC-dominated heavy compounds in CoSi family, such as AlPt and PdGa, and other spin-S fermionic excitations11 under the chiral Floquet engineering. Furthermore, we propose that light-induced electronic structure changes in CoSi could be detected via TrARPES and Mid-IR pumping and THz Kerr or Faraday probe spectroscopy experiments. Our findings propose leveraging chirality as an adjustable degree of freedom in Floquet engineering, paving new avenues to enable ultrafast switching of material properties and the development of innovative optoelectronic devices, such as chirality logic gates75 and chiral optical cavities76.

Methods

First-principles calculation

We applied the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)77 to perform density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate electronic ground states of the CoSi and AlPt compounds using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof-type exchange-correlation functional78. Projector augmented wave potentials79 were employed with a plane-wave energy cutoff of 300 eV. The BZ of the primitive cell was sampled using a Γ-centered 9 × 9 × 9 k-point grid. The convergence criteria for the electronic self-consistent calculation and force were set to 10−7 eV and 0.01 eV/Å, respectively.

We constructed the tight-binding Hamiltonian ({hat{H}}^{TB}({bf{k}})) from the ab initio calculations using maximally localized Wannier functions obtained from Wannier90 code80. d orbitals of Co (Pt) atoms and p orbitals of Si (Al) atoms were chosen as projected orbitals. The (001) surface projections of bulk states in Fig. 2c and d, as well as the surface states in Fig. 3, were obtained by extracting the spectral functions from the imaginary part of the bulk Green’s function:

and the surface Green’s function:

Here, Earc denotes the energy of the Fermi arc states, and ϵ is an infinitesimally small broadening parameter for the Fermi arc states. Gb(kx, ky, Earc + iϵ) and Gs(kx, ky, Earc + iϵ) are the bulk and surface Green’s functions, respectively, which were calculated by the iterative Green’s function method81. These calculation procedures have been merged into the open-source software package WannierTools82.

Floquet theory

The Floquet theory is a powerful mathematical tool that relates the time-periodic Schrödinger equation ({hat{H}}^{TB}({bf{k}},t){Phi }_{alpha }(t)=ihslash frac{partial }{partial t}{Phi }_{alpha }(t)) to a static eigenvalue problem in the energy domain. Herein, we construct the time-periodic tight-binding Hamiltonian or effective model by using the Peierls substitution

where e is the charge of electron, ℏ is the reduced Plank constant and A(t) is the vector potential of the pumping laser.

For the time-dependent Hamiltonian with one optical cycle T in Eq. (7), the Floquet theory guarantees the existence of solutions Φα(t) that can be expressed as

where Eα denotes the Floquet quasienergy and the periodic function uα(t) satisfies uα(t + T)= uα(t). Moreover, uα(t) can be expanded in a Fourier series with coefficients ({u}_{alpha }^{m}) as

where Ω = 2π/T is the frequency of the pumping laser. By substituting Eq. (8) and Eq. (9) into the original Schrödinger equation and performing some algebraic manipulations, we can derive an eigenvalue equation for the coefficients ({u}_{alpha }^{m}) and the corresponding eigenvalues Eα as

where ({hat{{mathcal{H}}}}_{nm}({bf{k}})=frac{1}{T}mathop{int}nolimits_{0}^{T}dthat{H}({bf{k}},t){e}^{i(n-m)Omega t}-mhslash Omega {delta }_{mn}) is the matrix element of the Floquet tight-binding Hamiltonian or Floquet effective model as (hat{{mathcal{H}}}({bf{k}})) and m, n are Floquet indices. We can diagonalize (hat{{mathcal{H}}}({bf{k}})) to obtain Floquet band structures of the CoSi crystal in the main text.

Responses