Chromosome-level genome assembly of Jaguar guapote (Parachromis manguensis) by massive parallel sequencing

Background & Summary

Parachromis managuensis (NCBI Taxonomy ID: 172535), commonly known as the jaguar guapote, belongs to the order Perciformes and the family Cichlidae within the genus Parachromis. This species is native to rivers and lakes in Nicaragua, Honduras, Costa Rica, and other Central American countries1. P. managuensis is a predominantly carnivorous, bottom-dwelling fish that helps regulate the overpopulation of smaller fish in freshwater ecosystems. It is recognized for its rapid growth, tolerance to low oxygen levels, high yield, strong disease resistance, and excellent meat quality2. These attributes have contributed to its increasing prominence as an economic fish species, leading to a significant expansion in its aquaculture. It is therefore regarded as an important tropical fish.

Research on P. managuensis at the molecular level is limited. In 2015, the mitochondrial genome of P. managuensis was sequenced3. Subsequently, in 2018, investigations into the adaptive evolution of P. managuensis at the transcriptomic level were conducted4. However, studies of its genome have not yet been reported, which significantly hinders the advancement of breeding programs and the development of desirable aquacultural traits. Recent advancements in sequencing technologies have markedly improved genomic research. Notably, Pacific BioSciences (PacBio)‘s Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) mode, available on the Sequel II platform, offers long read lengths (10–20 kb) and high accuracy (over 99%), thereby greatly benefiting de novo assembly studies of both plant and animal genomes5,6. High-quality reference genome sequences serve as the foundational prerequisite for advancing both fundamental and applied research in plants and animals. For example, the recent cat genome study, AnAms1.0, revealed over 1,600 novel protein-coding genes when compared to the previously utilized felCat9 assembly7. Furthermore, AnAms1.0 exhibits a higher count of structural variants and intact olfactory receptor genes compared to felCat9. These advancements play a crucial role in the discovery of novel genetic traits and in fostering advancements in veterinary medicine.

In this study, we report a chromosome-level genome assembly of P. managuensis by combining short sequencing reads, PacBio high-fidelity (HiFi) long reads, and chromosomal conformational capture (Hi-C) sequencing data. This high-quality assembled genome not only facilitates population genetic research and evolutionary analysis of P. managuensis but also provides important resources for optimizing genetic breeding.

Methods

Sampling, DNA and RNA extraction

Samples of P. managuensis were collected from Dagun Village, Lancang Lahu Autonomous County, Pu’er City, Yunnan Province (coordinates: E 100°27′95.11″, N 22°93′99.27″). Tissue samples were promptly collected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80 °C. DNA and RNA extraction, library construction, and sequencing in this study were performed using standard experimental and analytical protocols provided by NextOmics Biosciences (Wuhan, China).

Long read DNA preparation and sequencing

A total of 8 μg of high-quality genomic DNA was extracted from muscle tissue using a Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and concentration of the extracted DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. PacBio long insert libraries were prepared using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 according to manufacturers’ instructions, with an insert size of approximately 20 kb. The libraries were sequenced on the PacBio Sequel II system in CCS mode. Subreads were processed with SMRTLink (v11.1.0)8 using the parameters “–minPasses 3 –minPredictedAccuracy 0.99 –minLength 500”, producing approximately 21.70 Gb HiFi reads with an N50 size of 17,831 (Table 1). The parameter “minPredictedAccuracy” set to 0.99 in the context of PacBio SMRTLink software means that, during the data processing of sequencing reads, only those reads that have a predicted accuracy of 99% or higher will be retained for further analysis. This filtering step helps ensure that only high-quality reads, with a high likelihood of correct base calls, are included in the downstream processes, thereby improving the overall accuracy of the genome assembly.

Short read DNA preparation and sequencing

The extracted DNA (~5 μg) was randomly sheared into approximately 350 bp fragments, and a short fragment library was constructed using the MGIEasy Universal DNA Library Prep Set (MGI, China). Sequencing was conducted on the MGISEQ T7 platform (MGI, China), resulting in a total of 63.45 Gb of short sequencing reads, each 150 bp in length (Table 1).

Hi-C DNA library preparation and sequencing

A Hi-C library was generated using the DpnII restriction enzyme (GrandOmics, China). Muscle tissue samples were treated with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10–30 minutes to crosslink chromatin-interacting proteins. Subsequently, the DNA was digested with the restriction enzyme, and the 5′ overhangs were repaired with a biotinylated residue. A paired-end library with insert sizes of approximately 300 bp was prepared and then sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina, USA). A total of 151.09 Gb of clean data was obtained from 151.28 Gb of sequencing data using the software fastp (v0.19.5)9 with parameters “-w 20 –length_required 100” (Table 1). The “-w” parameter specifies the number of threads, while “–length_required 100” ensures that reads shorter than 100 bp are discarded.

RNA library preparation and sequencing

For the purpose of RNA sequencing, we extracted total RNA from gill and ovary tissues using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA purity was assessed with a NanoPhotometer spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, CA, USA), while RNA concentration was quantified using the Qubit RNA Assay Kit with a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA). RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on a HiSeq X-Ten instrument, generating 150 bp paired-end reads.

Genome size estimation

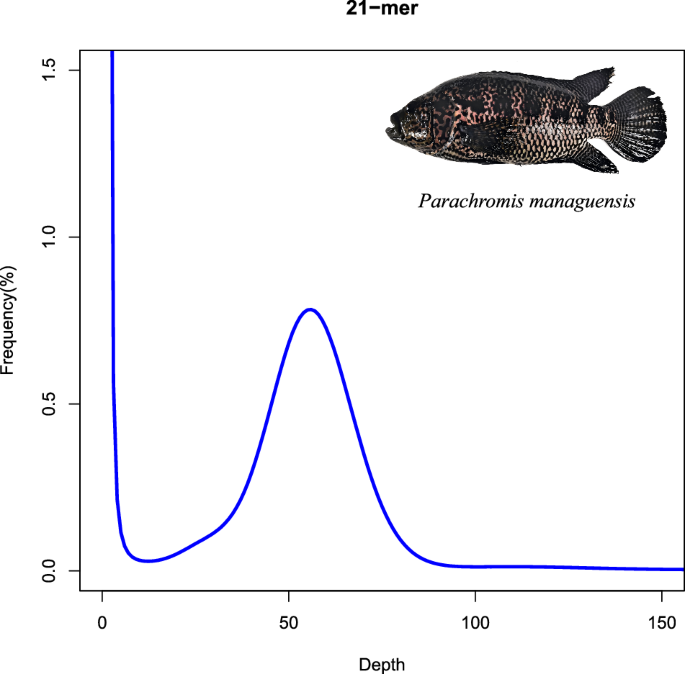

The genome size of P. managuensis was estimated through K-mer profiling. First, raw short sequencing reads underwent quality control using fastp (v0.19.5)9. Subsequently, a K-mer depth distribution curve was generated with Jellyfish (v1.1)10 using clean short sequencing reads. Base on the method described in the orange-spotted grouper study11, the genome size, G, can be calculated from the formula G = K_num/K_depth, where the K_num is the total number of K-mer, and K_depth denotes the frequency occurring more frequently than the other frequencies. In this study, K was 21, K_num was 52,215,706,815 and K_depth was 56. Therefore, the genome size of P. managuensis was estimated to be 932,423,335 bp (Fig. 1). The estimated heterozygosity rate was about 0.15% and the repeat content was approximately 29.31%, suggesting that it is not a complex genome.

K-mer distribution of P. managuensis genome sequencing reads. The X-axis is the depth of K-mer derived from the sequenced reads, and the Y-axis is the frequency of the K-mer depth.

De novo assembly and Hi-C assembly

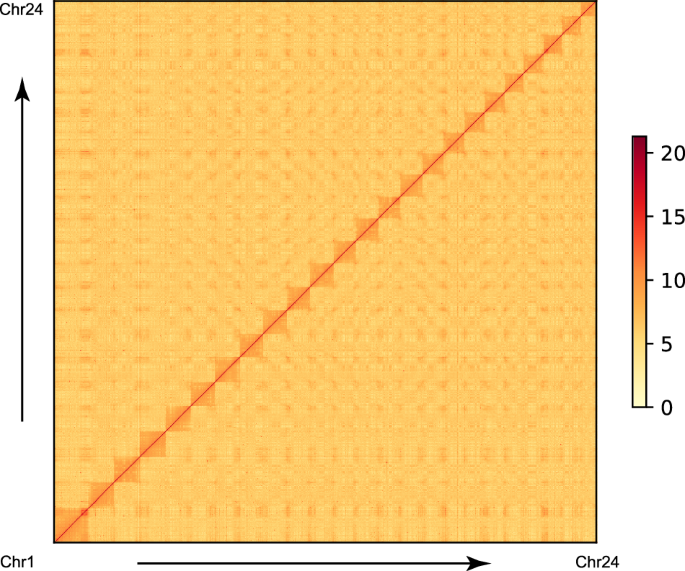

The primary contigs were assembled from HiFi reads using Hifiasm (v0.16.1)12 with default parameters. Three rounds of error correction were performed with NextPolish (v1.4.1)13 with both HiFi reads and short reads. This process resulted in 346 contigs, a total size of 896.65 Mb, and an N50 length of 5.14 Mb. To anchor contigs onto chromosomes, BWA (v0.7.12)14 was used to align the Hi-C clean data to the assembled contigs. Low-quality reads were filtered using the HiC-Pro pipeline15 with default parameters. The remaining valid reads were employed to anchor chromosomes using Juicer16 and the 3d-dna pipeline17, followed by manual correction with Juicebox (v2.13.07)18. Ultimately, approximately 99.10% of the contig sequences were anchored to 24 pseudochromosomes, with only 55 contigs remaining unanchored to chromosomes (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The longest and shortest pseudochromosomes were 56.13 Mb and 26.86 Mb in length, respectively (Table 3). The final genome assembly harbored a total size of 896.66 Mb with a scaffold N50 of 38.19 Mb (Table 2).

Hi-C assembly of chromosome interactive heat map. The abscissa and ordinate represent the order of each bin on the corresponding chromosome group. The colour block illuminates the intensity of interaction from yellow (low) to red (high).

Annotation of repetitive sequences

Tandem repeats and interspersed repeats were identified in this study. Tandem Repeat Finder (v4.10.0)19 and GMATA (v2.2.1)20 were used to discern tandem repeats with default parameters. The analysis revealed that simple sequence repeats (SSRs) account for 0.16% of the total genome length, while tandem repeat sequences comprised 0.69% of the genome length (Table 4). Subsequently, RepeatModeler (v1.0.4)21 and MITE-hunter22 were employed to construct a de novo repeat sequence library, which was then used to detect interspersed repeats and low-complexity sequences with RepeatMasker (v4.0.7)23. DNA transposable elements (TEs) were identified through RepeatMasker (v4.0.7). In detail, a total of 325.58 Mb (~36.31%) of repetitive sequences were obtained (Table 4). Among the interspersed repeats, DNA elements were the most prevalent type, accounting for 15.64% of the genome (Table 4).

Protein-coding genes prediction and function assignment

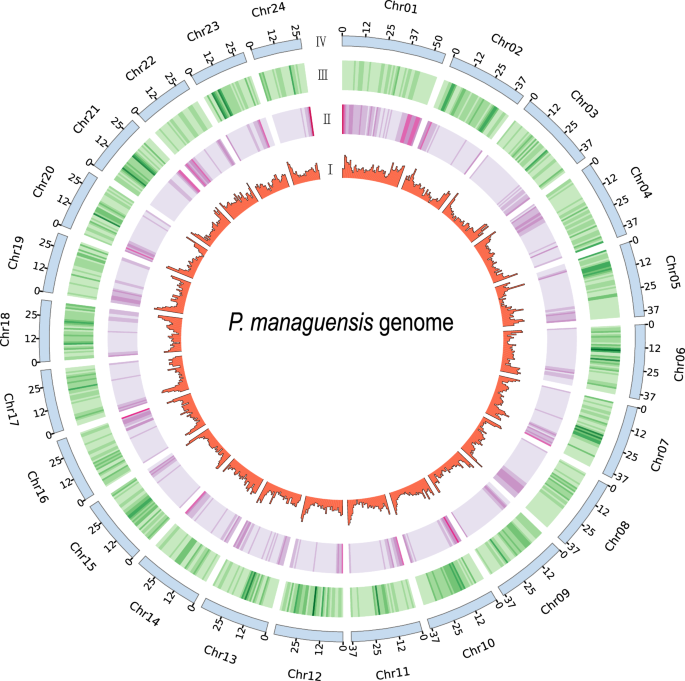

Gene prediction was performed using a multifaceted approach incorporating transcriptome-based, homology-based, and ab initio methods. For the transcriptome-based prediction, a total of 55.85 Gb of RNA-seq clean reads were aligned to the P. managuensis assembly using STAR (v2.7.3a)24 (Table 5). Stringtie (v1.2.2)25 was then utilized to assemble transcripts based on the alignment results. Afterwards, these assembled transcripts were aligned against the P. managuensis assembly using Program to Assemble Spliced Alignment (PASA) (v2.4.1)26. This process led to the identification of 22,712 genes, which were designated as the “RNAseq-set”. Genomes from five fish species were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database for homology-based gene prediction. The species included Oreochromis niloticus (GCF_001858045.2), Maylandia zebra (GCF_000238955.4), Neolamprologus brichardi (GCF_000239395.1), Astatotilapia calliptera (GCF_900246225.1), and Archocentrus centrarchus (GCF_007364275.1). O. niloticus is a well-studied fish with abundant genomic information and holds an important position in the field of fish biology and genomics research. It can provide a broad foundation of reference sequences and functional information for gene annotation of P. managuensis. M. zebra, N. brichardi, A. calliptera, and A. centrarchus all belong to the Cichlidae family and have a relatively close phylogenetic relationship with P. managuensis. These genomes were used as queries to search against the P. managuensis assembly using GeMoMa (v1.9)27, yielding 30,878 genes. Homology predictions were denoted as “Homology-set”. For ab initio prediction, 3,000 high-quality genes from PASA were randomly selected as the training set for model training with AUGUSTUS (v3.2.3)28. AUGUSTUS (v3.2.3)28 was then employed to predict coding regions in the repeat-masked genome, identifying 26,490 genes. The gene models generated by AUGUSTUS were labeled as the AUGUSTUS-set. Finally, all gene models were integrated using EvidenceModeler (v2.1.0)29. The weight of each evidence was set as follows: RNAseq-set > Homology-set > AUGUSTUS-set. The final comprehensive gene set comprised 24,145 genes, with an average of 10.53 exons per gene, an exon length of 167.11 bp, and a coding sequence (CDS) length of 1,760.01 bp. Circos (v0.69)30 was used to visualize the 24 pseudochromosomes, GC content, repetitive sequence density, and gene density (Fig. 3). The values for GC content were determined using SeqKit2 (v2.9.0)31. For the calculation of repetitive sequence density and gene density, bedtools (v 2.29.2)32 was employed and a window size of 1 Mb was set.

Circos plot showing the features of the assembled P. managuensis genome. From the inside to the outside, GC content, repetitive sequences density, and gene density, respectively.

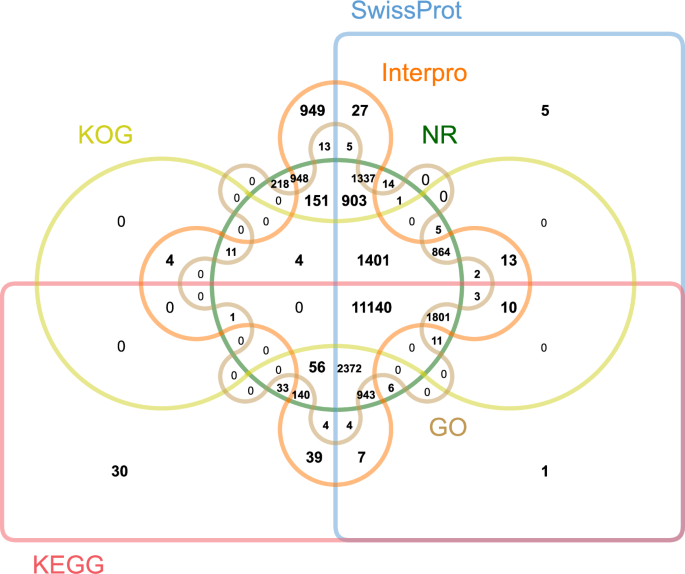

The integrated gene set was translated into amino-acid sequences and annotated using six public databases. Briefly, amino-acid sequences were aligned to EuKaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG)33, SwissProt34, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)35, and the NCBI nonredundant database (NR) using the BLSAT program (v2.7.1+)36 with an E-value cutoff of 1e-05. Protein domains were identified using the InterProScan (v5.30)37 program, and Gene Ontology (GO) terms for each gene were also extracted through InterProScan. Overall, 23,476 (97.23%) of the predicted protein-coding genes were functionally annotated (Fig. 4).

Venn diagram showing the number of genes with homology or functional classification by each method.

Data Records

All the raw sequencing data utilized in this study were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database with accession numbers SRP52769238 under BioProject number PRJNA1150327. The genome assembly has been deposited GenBank under the WGS accession GCA_040437545.139. Additionally, the genome assembly and annotation were deposited at Figshare40.

Technical Validation

Genome assembly and gene prediction quality assessment

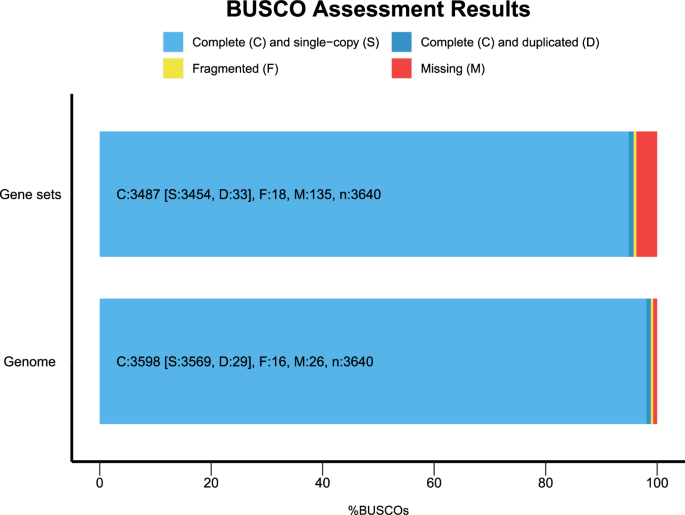

The precision and integrity of the P. managuensis assembly were evaluated using several methods. We utilized Merqury (v1.3)41 with PacBio HiFi long reads, employing a K-mer value of 17-bp to infer the consensus quality value (QV). Merqury assesses genome completeness by first defining reliable K-mers based on K-mer count histograms to set a threshold. Then, it calculates the fraction of these reliable K-mers in the read set that are also in the assembly. The results revealed a QV of 50.95 and a genome completeness of 98.28% (Table 2). Next, minimap2 (v2.24-r1122)42 and BWA (v0.7.12)14 were employed for aligning the HiFi reads and short sequencing clean reads to the P. managuensis assembly, respectively. Notably, 99.99% of HiFi reads and 99.51% of short sequencing reads were aligned to the genome. Referring to the genome study of Epinephelus coioides11 and Neosalanx taihuensis43, the completeness evaluation of the P. managuensis assembly was assessed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) (v5.5.0)44 with the actinopterygii_odb10 database. Results showed that 98.85% of the expected actinopterygii genes (including 98.05% single and 0.80% duplicated ones) had complete gene coverage, while 0.44% were identified as fragmented (Fig. 5). Furthermore, BUSCO analysis was also conducted to validate the genome annotation quality, which indicated that 95.80% of recognized BUSCOs, comprising 94.89% single-copy and 0.91% duplicated genes, were complete (Fig. 5). In conclusion, the P. managuensis genome assembly has achieved high quality.

BUSCO assessments of P. managuensis genome and gene sets.

Responses