Climate data for climate action

Climate science needs climate data

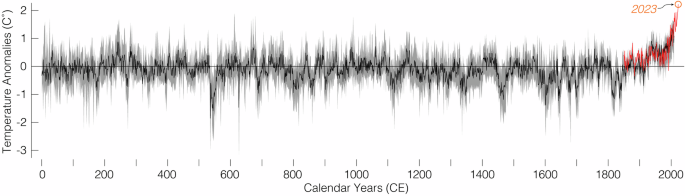

This Comment focuses on the still emerging ‘global climate change’ arena, in which easily accessible and freely available, physical and digital, climate data and associated computer codes are a fundamental precondition for reproducibility. Contextualising recent warming and disentangling the relative contributions of anthropogenic and natural climate forcing factors across different spatiotemporal scales, for instance, hinges on both the quantity and quality of temporally precise, seasonally distinct and spatially explicit proxy-based climate reconstructions that extend well beyond the modern period of meteorological measurements1 (Fig. 1). While “Climate models struggle to explain why planetary temperatures spiked suddenly.” and “More and better data are urgently needed.”2, the past two millennia offer a natural benchmark for evaluating the rate of rapidly changing recent temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere extra-tropics3.

Tree ring-based, annually resolved and absolutely dated ensemble reconstruction for Northern Hemisphere extra-tropical summer temperatures (black line)3,8, together with its 95% uncertainty range derived from the variance of individual ensemble members (grey shading). The reconstruction is scaled over the 1901–2010 period against instrumental June–August land surface temperatures from Berkeley Earth (red line)30 and expressed as anomalies with respect to the 1850–1900 mean3. The warmest summer on record is indicated separately.

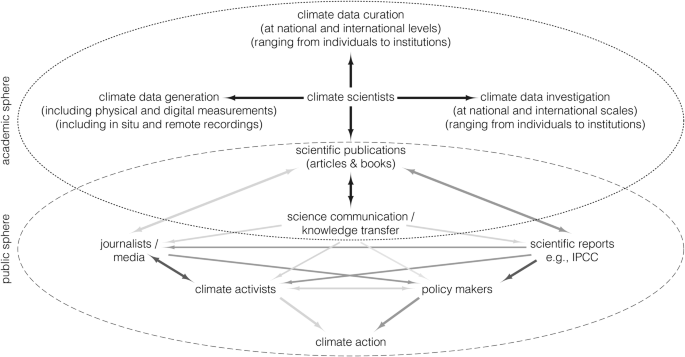

Forming the backbone of high-resolution palaeoclimatology (and thus impacting political and economic decisions at national to global scales), more than 6000 annually resolved and absolutely dated tree-ring chronologies are currently stored in the International Tree-Ring Databank (ITRDB)4. While this is a still-growing network with hundreds of new and updated sites submitted each year, future success will strongly depend on the willingness and ability of the international dendro community to make their chronologies freely available. For the Holocene, the ongoing interglacial that started approximately 11,700 years ago at the end of the last Ice Age5, more and spatiotemporally better-resolved climate reconstructions are needed6. Independent of the pre-industrial target period, be it the Common Era or the Holocene, high-quality climate proxy records, and hybrid proxy-model data assimilation products7 are critical for assessing and constraining the full range of reconstruction uncertainties8,9,10, which must be communicated unrestrictedly within and beyond academia. Moreover, any form of credible and sustainable climate activism is well-advised to be evidence-based. Likewise, policymakers and stakeholders need reliable information to develop climate change strategies and put in place and justify measures to mitigate the global greenhouse effect under predicted anthropogenic warming11. Hence, restricted access to and exchange of climate data, both observed and simulated, not only affects climate scientists but also climate activists and climate politics (Fig. 2).

Flow chart of climate data and knowledge-related interactions and dependencies between climate scientists (academic sphere), and climate activists and policymakers (public sphere). The generation (e.g., collection and recording) of climate data may include physical and digital measurements from in situ stations and remote sensing platforms, as well as computer codes. Both, the curation (e.g., archived and organised) and interpretation (e.g., analysed and evaluated) of climate data may happen on national and international levels and can range from the collaboration of individual scholars within and between countries to global institutional research networks. Publication and communication of scientific results and wider knowledge transfer are the interface between academic and public spheres. While any form of climate action and climate politics should be informed by climate data and research, climate scientists can and should operate independently of climate activists and climate politics31 – climate science does not need climate action, but climate action needs climate science.

Growing constraints for climate science

Further to the impacts of rising nationalism, bureaucracy and economic pressure12, and the effects of academic acceleration itself, e.g., ever-growing administrative tasks and economic demands13,14, recent geopolitical tensions hinder scientific relations and collaborations with scholars and institutions in many countries around the world15. Addressing and tackling the grand challenges of global climate change, however, requires the involvement of data and expertise from all regions and nations. For instance, as the world’s largest country that has the longest Arctic shoreline and the largest forest biome, peatland and permafrost zones, Russia plays an important role in global climate change research16. Without question, changes in the Earth’s biosphere and climate system cannot fully be understood without data from the terrestrial and marine Arctic and sub-Arctic, of which more than half lies within Russian territory. Similarly, climatological and environmental insights from the boreal forest in northern North America cannot simply be extrapolated to the high-northern latitudes of Eurasia17. While justified and unavoidable, Russia’s current isolation is hindering the generation, curation and interpretation of scientific data (Fig. 2), both space-born and ground-based.

Restricted data access and exchange affect predictions of the influence of anthropogenic climate change on natural and societal systems at different scales from local to global16. Inaccessibility of local permafrost observations from the high-northern latitudes hampers precise estimates of carbon pools and fluxes17,18, with biases in some cases as large as the predicted climate change signal by the end of the twenty-first century. Another example is tree-ring chronologies from remote regions in Siberia that are needed to understand how warming-induced changes in the functioning and productivity of the boreal forest influence carbon, nutrient, and water cycle dynamics19. Despite the enormous capabilities of rapidly advancing remote sensing products, these cannot fully replace in situ site measurements because of a lack of spatiotemporal resolution.

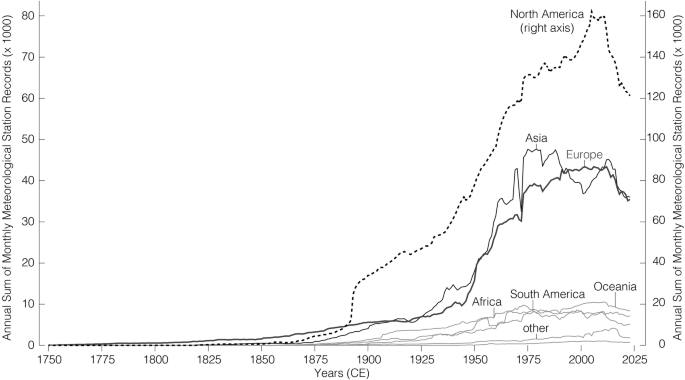

Further to the Russian dilemma16, data and knowledge transfer for the western hemisphere is also difficult with China and several countries in Africa and the Middle East. Political instability in different parts of the world has impeded, and may even cease, the exchange of climate and environmental data within and between various regions, with no foreseeable improvement. For example, national and international drought monitoring programmes not only in sub-Saharan Africa but also in large parts of inner Eurasia and the Americas are dependent on real-time data access, and any reduction in the quality and quantity of meteorological measurements implies potential long-term and large-scale consequences for food security and wildfire prevention20,21,22, amongst others. Early action needs early warning and early warning needs detailed monitoring and rapid knowledge transfer23. Counterintuitively, and in contrast to the overall exploding volume of climate data24,25, the number of freely available meteorological measurements at the global scale has been declining during the last decade (Fig. 3). The Asian data started to decline after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, and a substantial drop in weather stations since 2011 is evident even in North America. In addition to this temporal instability, the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere are spatially very much underrepresented. Spatial and temporal data gaps can hardly be compensated by gridded products, since interpolation masks local factors and processes. The causes of the change in the quantity (and quality) of weather observations are not singular26. While free access to and exchange of climate data has been taken for granted by many, the observed negative trend not only impacts individual scholars, smaller projects and larger organisations but will likely have knock-on effects in related fields of the natural and social sciences. A decline in easily accessible and freely available climate data will also affect forms of climate action and political decisions, which should always be informed by evidence.

The annual sum of monthly weather station recordings available to Berkeley Earth from 1750–2023 CE (update from ref. 30 but excluding 2024 to avoid bias from reporting delays). Data from North America are shown on the right y-axis that is twice as much as all others (left y-axis). Antarctica has the lowest number of weather station recordings (flat line at the bottom).

Likewise, climate scientists around the world are confronted with more demanding bureaucratic procedures and administrative hurdles to explore regions, perform observations, extract samples, and transport materials. This is alarming since free access to field sites, physical and digital measurements and computer codes, i.e., the Mertonian norm of ‘communality’27, describes a fundamental principle of academic work and good scientific practice. Experimental reproducibility and ethical integrity are directly related to unrestricted access and exchange of all kinds of data. On-ground operations are indispensable for installing and repairing instruments, maintaining and refining meteorological and other stations, updating existing and developing new proxy records and networks, exploring novel archives in remote regions, and calibrating and validating satellite imagery and other remote sensing products. There is also a worrying tendency towards unjustified costs for all kinds of physical and digital research data and computer codes, as well as far too intricate application processes and long waiting times for permissions that may, or may not, be granted for restricted periods of time, geographical regions and collaborative work tasks. These administrative and legal obstacles are particularly frustrating since scientific infrastructure, measurements and databases are typically funded by public tax money in the first instance. The negative consequences of reduced data access and exchange are not restricted to one country, but impact national and international collaborations, and will unavoidably affect future generations of climate scientists, policymakers, the wider public, and climate activists. Moreover, our concerns are not restricted to a particular academic discipline or research field. The same is true for social climate scientists who must conduct in-person interviews, visit libraries and gather evidence from archaeological, historical and modern sites28.

A global climate data convention

As a way forward, and in line with a new paradigm of more open, user-friendly access to climate data24, we call for a coordinated open-data policy well beyond existing protocols, such as those of the World Meteorological Organisation29. The policy must be implemented jointly and rigorously by universities and institutions, academies and organisations, journals and editors, as well as funding agencies and governments all over the world. We appeal to the scientific norm of communalism and argue for a consequent veto against any form of data commercialisation, in which research data are economically traded within and between institutions, organisations and administrations across national and international scales. We recommend a global treaty that ensures sustainable data access and exchange to support collaboration amongst climate scientists and stakeholders from different countries in maximising their needs while minimising potential harm.

A universal and legally binding climate data convention, endorsed by the vast majority of relevant actors, could deepen our understanding of the Earth’s climate system and foster the mitigation of anthropogenic climate change. Free data access and exchange, as well as rigorous science communication and knowledge transfer, are needed to address the grand challenges society will face under a warmer and more extreme future climate. A binding data convention will support climate science, climate action and climate politics alike (Fig. 2).

Responses