Clinical and genetic landscape of IRD in Portugal: pooled data from the nationwide IRD-PT registry

Background

Inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) comprise a wide group of clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorders. Despite being rare, they can lead to blindness from birth to late middle age and they are a major cause of inherited blindness worldwide1,2,3,4,5,6.

In the era of gene therapy, high levels of clinical suspicion and timely diagnosis are increasingly important7. According to recent guidelines on clinical assessment of patients with IRDs, genetic testing and genetic counselling are mandatory to confirm the diagnosis, improve the accuracy of prognosis and guide treatment decisions (eligibility for the FDA and EMA-approved voretigene neparvovec or consideration for any clinical trials)8,9,10,11. Moreover, genetic testing also facilitates the development of gene therapy, through increasing knowledge of molecular mechanisms involved in IRD pathogenesis12. As genetic testing costs have decreased, worldwide access to genetic testing has improved. Similar to the United Kingdom, costs of genetic testing in IRD in Portugal are covered by the national healthcare system13.

Developed countries have widely shared genetic profile and phenotype-genotype correlations in IRDs from different continents around the world, namely Europe14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, Asia22,23,24,25,26,27, America13,28,29,30, Africa31 and Oceania32. This has contributed to calculating the diagnostic yield of genetic testing in IRD, reporting new disease-causing variants and atypical presentations, as well as identifying ethnic and regional differences.

In Portugal, we have recently shown that the IRD prevalence varies between regions with different socioeconomic conditions33. However, information regarding the large-scale genetic and phenotypic profile of IRDs in Portugal is lacking. Currently, the most comprehensive study on Portuguese IRD patients was performed in a single Portuguese healthcare provider (HCP) and reported molecular assessment of 230 Portuguese IRD families34. Other studies reported even smaller cohorts with variants in certain genes of interest35 or specific clinical diagnoses36,37,38. Taking advantage from the well-established IRD-PT registry (retina.com.pt)39, a national, web-based registry specifically developed for IRD, this study aims to characterize the clinical spectrum and genetic landscape of IRDs in Portugal by pooling data from all the contributing HCP.

Results

Geographic distribution

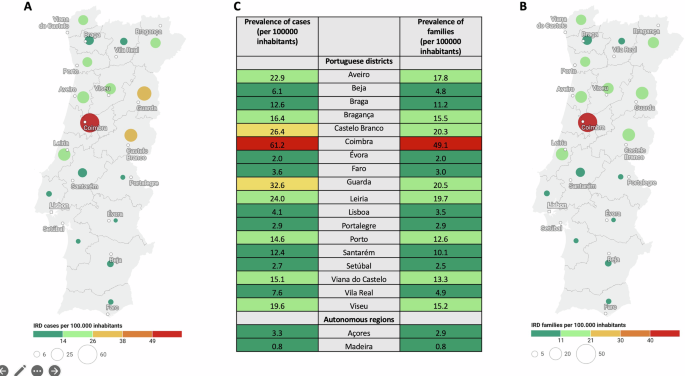

Our study enroled 1369 patients from 1125 families, who underwent genetic testing for IRD. Considering that Portugal has 10343066 inhabitants (census 2021)40 and IRDs have an overall prevalence of 1:3000 individuals41, estimates point towards 3448 Portuguese IRD patients. Therefore, this cohort likely represents about 39.7% of the IRD patient population in Portugal. The regional distribution of cases and families with respective prevalence can be seen in Fig.1. In our cohort, the districts with a higher prevalence of cases and families were: Coimbra (61.2 cases and 49.1 families per 100,000 inhabitants), Guarda (32.6 cases and 20.5 families per 100,000 inhabitants), Castelo Branco (26.4 cases and 20.3 families per 100,000 inhabitants), and Leiria (24.0 cases and 19.7 families per 100,000 inhabitants).

Relative values of prevalences considering individual cases (A) and families (B) are represented in a coloured map of Portugal (excepting autonomous regions of Azores and Madeira). Absolute values of prevalences considering individual cases and families in each administrative region (including autonomous regions of Azores and Madeira) are represented in table (C). This figure was created using the tool datawrapper (© 2023 Datawrapper developed by Datawrapper GmbH and available on the website datawrapper.de).

Clinical data

Males and females were almost equally represented among the cohort (51.6% vs. 48.4%). By removing cases due to variants in X-linked genes, the sex balance was 49.8% males vs 50.2% females. The cohort’s mean age was 39.8 ± 19.4 (ranged 1 to 86 years).

More than 1/3 of patients (36.6%) presented with initial symptoms between 6 and 20 years of age, while 15.2% presented symptoms before 5 years of age, 21.7% between 21 and 50 years, and 26.5% after 51 years of age. History of consanguinity was present in 20.2% and positive family history in 52.7% of the cases. The districts with an above-average consanguinity rate were: Castelo Branco (40.4%), Leiria (23.6%), Lisboa (23.1%), Coimbra (22.4%), Guarda (22.2%) and Viseu (21.4%), if we exclude districts with less than 20 cases.

Clinical phenotypes were distributed across 44 ORPHA diagnoses. Isolated and syndromic forms of IRDs represented 78.6% and 21.4%, respectively. Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (ORPHA 791), Stargardt disease (ORPHA 827) and cone and cone-rod dystrophies (ORPHA 1872) were the most frequent diagnoses (40.8%, 8.6% and 8.2% respectively). Among the syndromic phenotypes, Usher syndrome (ORPHA 886) was the most common (representing 7.0% of the total sample and 32.8% of the syndromic sample), followed by Bardet-Biedl syndrome (ORPHA 110) (representing 2.7% of the total sample and 12.6% of the syndromic sample). Distribution by clinical diagnoses including the respective ORPHA numbers can be seen in Table 1.

Molecular genetic composition of the cohort

The overall diagnostic yield (genetically solved rate) was 72.3% (813/1,125 families). An inconclusive test was obtained in 17.2% of families, while partially solved results were seen in 10.6% of families. The diagnostic yield varied widely depending on the clinical phenotype, ranging from 0 to 100% (Table 1). The zygosity also impacted in overall diagnostic yield. Excluding homozygous solved cases, the diagnostic yield decreases to 61.1%.

Disease-causing genotypes were distributed across 136 different genes. Although there is a wide spectrum of genes, 113 were represented in 1% or less of the cohort. The 10 most frequently implicated genes (by number of affected families) were as follows: ABCA4 (13.0% of families), EYS (10.0% of families), USH2A (6.9% of families), RPGR (3.7% of families), RHO (3.3% of families), RS1 (2.6% of families), ABCC6 (2.5% of families), RPE65 (2.5% of families), MYO7A (2.1% of families) and PRPH2 (2.1% of families). These accounted for 48.6% of all molecularly characterized families. Table 2 summarizes the distribution of these genes in the solved cohort. Figure 2 illustrates numbers affected by the 26 most frequently implicated genes (by number of affected families and numbers of affected individuals, upper and lower panels, respectively). When genes were ranked by the number of individuals affected, rather than families, autosomal dominant genes, as expected, moved slightly upwards in rank (e.g., PAX6, VCAN, IMPG2).

A Genes ranked by numbers of affected families. B Genes ranked by numbers of affected individuals.

Among the genetically solved families, 89.8% showed causative variants in autosomal genes (most frequently ABCA4, EYS, and USH2A), 8.4% in X-linked genes (most commonly RPGR, RS1, and CACNA1F) and 1.8% in mitochondrial genes (most widely MT-TL1 and MT-ATP6). Of the autosomal genes, 81.1% of families showed variants in genes in which disease-causing variants are recessive (43.5% compound heterozygous and 56.5% homozygous) and 18.9% of families showed variants in genes in which disease-causing variants are dominant.

For patients with autosomal dominant RP, the most frequently associated gene was RHO; for X-linked and autosomal recessive forms of RP, the most frequently associated genes were RPGR and EYS, respectively. For macular dystrophies, the most common gene by far was ABCA4 (autosomal recessive), whereas PRPH2 and BEST1 were implicated frequently in autosomal dominantly inherited macular dystrophies.

Six hundred and seventy-one different variants were detected in the entire cohort (Supplementary Data 1). The most common variants (by number of affected families) are described in Table 3. Table 4 shows variants detected in more than 5% of characterized families, by Portuguese regions. All these variants are depicted in Table 3 of IRD most frequent causing variants.

In the solved paediatric cohort (under 18 years of age), disease-causing genotypes were distributed across 47 different genes and the most common genes (by number of affected families) were ABCA4 (n = 12 families), RS1 (n = 7), RPGR (n = 6), BEST1 (n = 5), NMNAT1 and PAX6 (n = 4 each). Figure 3 illustrates numbers affected by the 15 most frequently implicated genes (by number of affected families and numbers of affected individuals, upper and lower panels, respectively).

A Genes ranked by numbers of affected families. B Genes ranked by numbers of affected individuals.

In the solved syndromic cohort, disease-causing genotypes were distributed across 61 different genes and the most common genes (by number of affected families) were USH2A (n = 34 families), ABCC6 (n = 20), MYO7A (n = 17), BBS1 (n = 14), and ADGRV1 (n = 9).

Figure 4 illustrates the types of testing used alone or in combination in the entire sample. There were few cases not represented in this Euler diagram: 63 cases with known molecular results, but the type of test performed was unavailable in the registry (missing data); 11 cases who performed Sanger sequencing of the RPGR ORF15 region alone (n = 3) or in combination with other tests (n = 8); 2 cases who performed both targeted variant testing (family variant analysis) and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA); 2 cases who performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS); and 1 case performed both Sanger sequencing and whole exome sequencing (WES).

FVA Family variant analysis, MLPA multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, NGS next-generation sequencing-based panels, SS Sanger sequencing, WES whole exome sequencing-based panels. This figure was created using the tool eulerr (available on the website eulerr.co).

Discussion

Achieving strong population-based data is the first step towards better genetic and prognostic counselling as well as guidance for future therapeutic interventions. This nationwide multicentre study reports the genetic landscape of the largest cohort of Portuguese IRD patients to date, including 1369 patients from 1125 families. Although there are recent studies with larger samples in other countries14,15,16,21,24,25,30, this study represents around 40% of the estimated IRD patient population in a single country, a figure higher than those reported and estimated in other studies (Table 5).

Regarding the regional case distribution, there was a higher prevalence of IRD cases in districts of the country’s centre region (Coimbra, Guarda, Castelo Branco and Leiria). This is consistent with the municipalities previously identified as having higher IRD prevalence in Portugal: Góis (Coimbra), Oleiros (Castelo Branco), Penacova (Coimbra), Vila de Rei (Castelo Branco), Pampilhosa da Serra (Coimbra) and Seia (Guarda)33. Except for Lisboa, districts of the country’s centre region (Castelo Branco, Leiria, Coimbra, and Guarda) had a higher consanguinity rate probably contributing to its higher IRD prevalence. “Hotspots” due to a high rate of consanguinity/homozygosity may allow for an earlier diagnosis, further increasing the difference between regions14,34,42. Another possible reason can be the disease awareness inside the communities as well as smaller distance to a referral tertiary hospital33.

The fact that more than 50% of patients initiated symptoms before 20 years of age highlights the importance of early identification of the clinical picture, with significant implications for the future of the affected patients and their families. Consanguinity was identified in about 1/5 of cases, explaining an enrichment in homozygous variants in this cohort. Specifically, among the autosomal recessive genes, 56.5% of families showed variants in homozygosity, similar to the Argentinian cohort (54%)13, higher than some Italian (31.2%) and Polish (25.5%) cohorts16,18, but much lower than Arab countries (93%)22.

While in most cases of IRD the disease is limited to the eye (non-syndromic), over 80 forms of syndromic IRD have been described43. Additionally, it has been estimated that up to 30% of IRD are syndromic44. Most of these syndromes are so rare that they can be underdiagnosed, explaining their lower representation in our cohort (21.4%) and in other cohorts (between 10 and 23%)16,19,20,26,28,44,45,46.

In addition to being representative, this study achieved a highly satisfactory detection rate (72.3%) of disease-causing genotypes using clinically oriented genetic testing, with only two recent studies reporting a slightly higher solved rate (76% and 72.9%)28,34, despite having smaller samples (Table 5). Homozygous cases can contribute to this high accuracy because, when we excluded them, the diagnostic yield decreased to 61.1%.

Pathogenic variants in over 280 genes are now known to cause IRD, with multiple modes of inheritance47. Overall, our cohort shows a good genetic coverage, with disease-causing variants identified across 136 genes. This surpasses the number of genes identified in the British cohort, which is the largest published molecularly-solved IRD cohort to date, and trails only the Spanish cohort, which has identified 142 genes. (Table 5).

Regarding disease-causing genotypes, this study confirmed that EYS gene is more frequently implicated than what is commonly observed in other European cohorts (Table 5), as evidenced in previous studies34,35. Netherlands and Switzerland were the only European countries with EYS in the top 5 of most frequently implicated genes (second and third position, respectively)20,48.

Analysing other cohorts worldwide, we found that the EYS gene was also frequently implicated in Asian cohorts, namely in Japan (the most implicated gene), South Korea and Taiwan (the second most implicated gene in both), China and Israel (the fifth most implicated gene in both)23,24,25,44,49.

Nevertheless, at least in Japan, the high frequency of EYS-related disease might be linked to variants different from those in our cohort. For example, the variant EYS (NM_001142800.2): c.2528 G > A was found in 381 alleles in the genome aggregation database (gnomAD)50 for Asia but in none in Europe, suggesting it is a probable founder variant in Asia. Considering the most frequent EYS variants in our cohort through the gnomAD, EYS (NM_001142800.2): c.4120 C > T was found in 17 alleles (8 American, 6 European and 3 others) and EYS (NM_001142800.2): c.5928-2 A > G in 33 alleles (17 European, 15 American and 1 other), meaning that they are probably variants of European origin34,51,52,53. EYS (NM_001142800.1): c.(2023 + 1_2024-1)_(2259 + 1_2260-1)del variant has only been reported in a Spanish and a Portuguese/Brazilian cohort in a lower prevalence than our cohort, suggesting a probable founder effect in the Portuguese population54,55.

Our study also showed the most frequent variants detected across the country and regions with higher prevalences. The two most common EYS variants appeared to be more frequent in the centre region of country, namely EYS (NM_001142800.1): c.(2023 + 1_2024-1)_(2259 + 1_2260-1)del in Castelo Branco and Coimbra and EYS (NM_001142800.2): c.4120 C > T p.(Arg1374*) in Leiria, where a founder effect could be happening35. Contrasting, three of five most common ABCA4 variants appeared to be more frequent in the north of the country, namely ABCA4 (NM_000350.3): c.1804C>T p.(Arg602Trp) in Aveiro, and ABCA4 (NM_000350.3): c.3210_3211dup p.(Ser1071Cysfs*14) and ABCA4 (NM_000350.3): c.4926 C > G p.(Ser1642Arg) in Braga, where another founder effect could be happening.

One of the strengths of this study is its multicentric design, which includes all IRD patients enroled in the IRD-PT registry until March 2024 (database closure), pooling together a significant sample of patients nationwide, its regional distribution in the country and avoiding repetitive cases.

Nevertheless, this study is not exempt of limitations. The districts where IRD patients currently live were evaluated, but not the family’s district of origin. Therefore, IRD prevalence may be biased by migration from the interior to the coast (from rural to urban environments) that occurred in Portugal a few decades ago33. Furthermore, patients not yet registered on the platform were not included. Not all IRD patients are followed up in ophthalmology departments which are actively enroling patients in the registry (either due to lack of time, acknowledgement, or lack of motivation)56. A previous study identified that regions with lower diagnosis rates are in rural areas of the country probably due to less access to health care33. This may be more significant in districts of the country’s south region and autonomous regions of Azores and Madeira, less represented in this study. The high prevalence of IRD in the Coimbra district can also be due to referral bias, given that this is the only HCP affiliated with the ERN-EYE. Additionally, our national registry started later than other consortiums or databases from other countries cohorts, consequently having fewer patients: Spain (since 1991), Italy (since 1991), United Kingdom (since 2003), USA and Canada (since 2006), Germany (since 2010), Japan (since 2010), and Israel (since 2013)15,16,21,24,25,30,46. The IRD-PT pre-launched in mid-2019 in a single HCP (currently ULSC), with posterior progressive inclusion of other HCPs56. We consider that in the last 5 years, we achieved a reasonable national cohort representation (Table 5). Lastly, given the high consanguinity rate, dual or blended diagnoses could be expected. However, the IRD-PT registry was not designed to capture other diseases than IRDs and data about other genetic diagnoses is not available.

This is a pioneer study, shedding light on the clinical and genomic landscape of IRDs in Portugal and opening avenues for future intervention. Overall, we identified 329 patients (31.7% of the solved cohort) with variants in potential genotypes for therapeutic approaches (namely gene therapy-based) that are either already available [e.g. Luxturna for RPE65 (n = 26)] or are currently being tested in advanced clinical trials (Phase II/III) e.g. ABCA4 (n = 124), RPGR (n = 76), RS1 (n = 27), USH2A-exon13 (n = 16), PDE6A (n = 10), CNGB3 (n = 10), MERTK (n = 8), CHM (n = 8), CNGA3 (n = 7), PDE6B (n = 6), CEP290 (NM_025114.4):c.2991+1665 A > G (n = 5), RLBP1 (n = 3), and GUCY2D (n = 3)57,58,59,60.

In the future, we hope that the number of molecularly diagnosed patients will increase. The growth of the national registries worldwide will assist in knowing the molecular epidemiology of IRDs and validate public health and social measures, as well as stimulate research efforts for the development of therapeutic options due to a growing number of patients recognized. In addition, they also describe the natural history of these diseases, giving information about the evolution of some variants in each population35.

Methods

Study design

A nationwide, multicentre, cross-sectional, cohort study was conducted, involving the six Portuguese HCP that were actively enroling patients in the IRD-PT registry (retina.com.pt) at the time of database closure: Unidade Local Saúde de Coimbra (ULSC), Unidade Local Saúde de Santo António (ULSSA), Unidade Local Saúde de São João (ULSSJ), Unidade Local Saúde de Braga (ULSB), Unidade Local Saúde de Santa Maria (ULSSM) and Unidade Local Saúde de Almada-Seixal (ULSAS). The IRD-PT registry (retina.com.pt) is a national, web‐based, interoperable registry for IRDs, developed in 2019 and designed to generate scientific knowledge and collect high‐quality data on the epidemiology, genomic landscape and natural history of IRDs in Portugal39,56. The platform allows registration by the national health user number, compiling records from different hospitals in the same clinical file, anonymized for each centre, avoiding the inclusion of repetitive cases.

Patient selection and ethical statement

Consecutive patients with a clinical diagnosis of IRD and available genetic results, enroled in the IRD-PT registry until March 2024 were included. Incomplete or incongruent data exported by the platform was checked and corrected by each IRD specialist and their collaborators, between April and June 2024. Patients who did not undergo genetic testing or whose genetic testing results were pending at the database closure were excluded from this analysis.

Every patient provided written informed consent before enrolment, and the study complied with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for biomedical research. Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee approval was obtained from the Departamento de Ensino, Formação e Investigação (DEFI) of Unidade Saúde Local de Santo António with reference number 2021.269(216-DEFI/224-CE). Of note, the study includes data that has been featured in previous publications35,36,37, however most of the data shown here has never been published.

Clinical/demographic data

Prior to enrolment in the IRD-PT registry, all patients were observed by a retina specialist and underwent a complete ophthalmological examination complemented by multimodal retinal imaging. Demographic and clinical data included: age, gender, district of residence, age of onset of disease-related symptoms, clinical phenotype, presence of consanguinity, family history, genetic test state, disease-causing genotypes, inheritance pattern and zygosity.

All IRD cases are coded in the IRD-PT registry according to the Orphanet Rare Disease Ontology (ORPHA codes) to characterize the phenotypes better. The IRD-PT registry is longitudinal and allows the capturing of natural history data over time. New visits are added every time the patient visits the HCP and can also be included retrospectively (the registry launched in 2019 but for some patients we have clinical data with more than 30 years of follow-up). Some diagnoses have changed over time. Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we consider only the current clinical diagnosis for our analysis. This registry excludes suspicious phenocopies, defined as nonhereditary phenodeviations that may closely mimic RP mutant phenotypes (e.g., post-inflammatory conditions, traumatic sequelae, neoplastic or non-neoplastic autoimmune retinopathy).

Genotyping methods

Genetic testing was clinically-oriented in all probands and included Sanger sequencing, MLPA, next-generation sequencing (NGS) IRD panels, WES-based panels or WGS; whenever possible, segregation analysis was performed in family members. Variants were classified in accordance with the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)61. Cases were classified as solved when pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified with consistent allelic phasing and phenotypic correlation to known literature for the gene. Partially solved cases were considered if a single disease-causing variant was found in a recessive gene compatible with the phenotype or cases harbouring one or more variants of uncertain significance (VUS) compatible with the phenotype. Cases with no genetic findings or findings not compatible with the patient’s phenotype were classified as unsolved. Only the solved cases were considered to calculate the diagnostic yield. Genetic counselling provided by a medical geneticist was granted to all families.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS programme (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28.0.1.0 for Mac). Figure 1 was made with the tool datawrapper (© 2023 Datawrapper developed by Datawrapper GmbH and available on the website datawrapper.de)62. Fig. 4 was made with the tool eulerr (available on the website eulerr.co)63.

Responses