Close relationship partners of impartial altruists do not report diminished relationship quality and are similarly altruistic

Introduction

Impartial altruism is a widely-held moral ideal. Its value is enshrined in foundational religious and philosophical texts, from the Bible’s parable of the Good Samaritan to Buddhism’s Metta Sutta, which positions universal love among the highest aspirations, to contemporary teachings on effective altruism, which argue social and physical distance should not influence decisions to help1,2. Laboratory research also finds that typical adults view impartial helping as the most morally praiseworthy, at least in the abstract3. And yet impartial altruism remains rare, and it is not always lauded in practice. This may be because many social relationships, such as between spouses or close friends, entail special moral obligations that undermine impartial altruism4. And when impartiality is pitted against relational obligations, most people view it as more appropriate to prioritize social closeness5,6. When people fail to help a family member, they are judged as morally worse than those who fail to help a stranger3,6,7, perhaps because helping strangers is seen as supererogatory rather than obligatory3. And impartial, utilitarian agents who do prioritize helping distant others over less-needy close others are seen as less warm, less morally good, less trustworthy, and less desirable as friends relative to agents who prioritize close others6,7. This suggests impartial altruism may be admired in theory but rare in practice in part because it carries (or is perceived to carry) costs to close relationships.

We thus conducted a series of pre-registered (https://osf.io/g7xc6/), laboratory studies assessing whether impartial altruism necessarily comes at a cost of lower-quality close relationships. We developed an impartial decision-making task to behaviorally assess impartial altruism. We adapted the first-person social discounting paradigm8 (wherein participants elect to keep money for themselves or split it between themselves and a social other) to assess third-party decision-making (wherein participants elect to keep the money for a close social other or split it between a close social other and a more distant social other) to determine how people make valuations between close and distant others. We administered both the first-person social discounting paradigm and our third-party social discounting paradigm to pairs of close others. Participants included a sample of adults who had engaged in a canonical real-world act of impartial altruism: altruistic living kidney donors (and their socially closest other as their study partner). Several lines of evidence indirectly support the notion of such donors’ impartial altruism. Beyond their willingness to engage in costly, non-normative generosity for an anonymous stranger, these altruists also exhibit heightened altruism toward socially distant others in the laboratory. They engage in reduced social discounting, such that their generosity towards others decreases minimally as social distance increases8,9,10. Relative to controls, these altruists show increased self-other overlap in neural responses to strangers’ distress11; subjectively value distant other’s well-being12; and preferentially endorse impartial beneficence, or the ideal of helping others regardless of social closeness, on the Oxford Utilitarianism Scale13. By contrast, altruists score no higher than controls in measures, such as self-reported empathy, conscientiousness, or risk sensitivity10. However, it remains an open question whether altruists show relatively less favoritism than typical adults for close versus distant others.

Operationalizing impartial altruism as objectively measured real-world costly altruism overcomes some shortcomings associated with the exclusive use of laboratory measurements of altruism, which cannot ethically assess genuinely risky or costly altruism. Furthermore, it mitigates the social desirability and norm adherence motives associated with self-report measures, scores on which do not reliably correspond to real-world altruistic behavior14. We compared altruists and their close others to typical adults and their close others as they completed a first-person social discounting task in which they were able to make selfish or generous choices for socially close and distant others8,10,15.

Social discounting is a direct measure of generosity, but an indirect measure of impartiality. A more direct test of impartial altruism would explicitly require participants to divide resources between closer and more distant others, such that resources could either be divided equally (impartiality) or allocated to the close other (favoritism). Moral judgment studies find this to be an essential distinction, with helping distant others viewed by most people as a moral good only when it does not come at a direct cost to close others3,6. We thus created our third-party social discounting task to mirror the design of a first-person social discounting task but required participants to choose how to allocate actual resources between closer and more distant others. We predicted that real-world impartial altruists would show greater impartiality than typical adults in this task.

What remains an open question is whether impartial altruism is associated with relationship quality with close others and whether real-world altruists, on average, have poorer-quality close relationships than typical adults. Of note, the only individual raters who do not view impartial altruists as less desirable friends are those who are more impartial themselves7. This suggests value homophily–preferential formation and maintenance of close relationships with those who share similar values, attitudes, and beliefs4,16,17,18,19,20—could buffer the costs of real-world impartial altruism in close relationships. If altruists’ close others are similarly impartial, this value homophily could serve as a potential protective factor.

Homophily in both prosocial and antisocial values has been found to predict improved relationship quality, though not all values have such effects. Similarity in self-direction values (interest in independent thought and action, expressed in choosing, exploring, and creating21) has been found to predict higher relationship satisfaction in opposite-sex spousal pairs22. Meanwhile, other values more closely related to impartiality, such as benevolence (concern for the welfare of one’s ingroup21), are not predictive of relationship quality. And though same-sex spousal pairs exhibit similar levels of universalism (concern for the welfare of all beings)21 to each other, this similarity is not predictive of relationship quality22. But similar levels of some antisocial traits, such as narcissism and psychopathy have been found to predict increased relationship quality in heterosexual romantic pairs23. Could similarity in impartiality serve as a similar protective factor for altruistic pairs?

We sought to directly test the prediction that real-world altruists would exhibit true impartial altruism, sacrificing close others’ resources to benefit more distant others. We next tested whether this tendency carries social costs in altruists’ close relationships. We predicted that any such difference would not predict group differences in relationship quality between altruist dyads and control dyads if we also observed homophily in impartial discounting across friend pairs for altruists and controls, such that altruists’ socially close others would also exhibit significantly more impartial generosity than controls’ socially close others. As for why altruists exhibit increased impartial altruism in the third-party social discounting task, we hypothesized and tested three potential psychological mechanisms: One hypothesis is that impartial decision-making is driven by a generally heightened concern for impartial beneficence–that is, altruists’ increased impartial generosity could be significantly predicted by a generally heightened concern for impartial beneficence (as measured through the Oxford Utilitarianism Scale24); a second, related hypothesis is that impartial third-party social discounting is driven by a lack of moral tolerance for social others who might prefer favoritism (on their own behalf) over impartiality–that is, no matter what social others might prefer, impartial decision-making is determined by the decision maker’s moral dogma of impartiality; lastly, the third hypothesis is that individuals use their own first-person social discounting tendencies as a cognitive anchor25 when engaging in third-party social discounting, such that impartial decision-making is driven by an overreliance on how oneself would socially discount and a failure to properly adjust to social others’ differing preference sets25, resulting in a form of consensus bias, or the implicit view that others share one’s own beliefs and preferences26. We tested the first two hypothesized mechanisms by investigating the predictive roles of impartial beneficence and moral tolerance/relativism on third-party social discounting behavior; and we tested the last hypothesized mechanism by investigating the predictive role of first-person social discounting behavior on third-party social discounting behavior. For the social discounting task to have real stakes, participants were informed at the start of the study that their decisions were yoked to real-world consequences wherein one of their choices would be randomly selected for a payout to the participants and/or their nominated social other(s).

Methods

Participants were recruited through our database of verified altruistic kidney donors in North America and controls. Additional controls were recruited via the online recruitment database ResearchMatch. Interested participants invited their socially closest other, described as their “closest friend, partner, or relative,” to contact the researchers independently. Once both participants in a dyad agreed to participate, they were instructed to separately complete a survey using Qualtrics. All materials were approved via the Georgetown University IRB.

Recruitment procedures are described in the pre-registration and approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board. The study was performed in accordance with approved guidelines and regulations, and informed consent was provided by all participants.

260 participants completed all laboratory tasks, exceeding our target sample size (N = 208), but in accordance with our preregistered stopping rule (N = 260). Preregistration was registered on April 26, 2022 is available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/g7xc6/). The sample included 59 altruists, 59 close others of altruists (nominated by altruists as their closest other), 71 controls, and 71 closest others of controls. Only participants in a complete dyad (wherein both partners completed the survey) were included. Altruists and controls were closely matched in gender distribution (x2 = 0.06, df = 1, p = 0.806) and race/ethnicity (x2 = 0.08, df = 1, p = 0.777; see Table 1). However, following exclusions, the altruist sample was slightly older (Maltruists = 54, Mcontrols = 47, t = 2.21, df = 109.2, p = 0.03) and higher in income (Maltruists = $90,000–179,999, Mcontrols = $60,000–89,999, x2 = 11.35, df = 1, p = 0.0008). Altruists’ closest others and controls’ closest others were similar in gender distribution, education level, and race/ethnicity. Altruists’ closest others, however, were older (Maltruists’ friends = 56, Mcontrols’ friends = 47, t = 3.08, df = 124.7, p = 0.003) and had higher household income (x2 = 9.53, df = 1, p = 0.002) compared to controls’ closest others. Thus, we controlled for gender, age, and income in all analyses. Because income and education are typically highly correlated, our preregistered analyses did not include both factors in statistical models in order to reduce collinearity27. Altruists and controls did not differ significantly in relationship type (i.e., spouse, friend, roommate, etc.; see Fig. S1 in the SI) across nominations.

All participants completed a first-person social discounting task8,9,28. The task was structured into seven blocks, each containing nine trials. Following established protocols29, participants were first instructed to provide the names of individuals from their personal social network: “Imagine a list of 100 people in your social circle, with person #1 representing the closest relationship and person #100 being someone completely unfamiliar to you.” Participants then entered names of people at social distances N = 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 50, with N = 100 representing a nameless stranger. Participants then were asked to make nine binary decisions concerning retaining and/or sharing specific amounts of money with each of these individuals. In each trial, participants had to indicate whether they preferred to keep a sum of money exclusively for themselves (the selfish option) or to retain a sum of money for themselves while also sharing an identical amount with the Nth person on their list (the generous option). The selfish options involved keeping varying amounts of money, ranging from $155 down to $55, decreasing in $10 increments. On the other hand, the generous option consistently entailed keeping a fixed amount of money and sharing that same amount with the Nth person (i.e. “$75 for you, $75 for [N]”). Participants were required to confirm their knowledge of each N’s identity before task initiation.

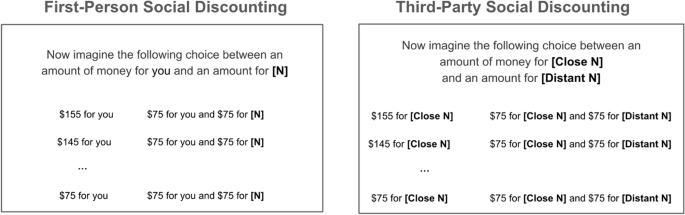

They next completed our third-party social discounting task created for this research protocol to assess third-party social discounting. Its design closely parallels a first-person social discounting task, except participants allocate money between closer and more distant others (e.g., allocating $145 to N = 1 (favoritism) versus splitting $150 evenly between N = 1 and N = 50 (impartial). Because the third-party task requires choosing to favor a close other versus impartiality, the number of choices decreases as the social distance of the close other increases (Fig. 1).

Dichotomous social discounting choices in the first-person (left) and third-party (right) social discounting tasks, where [N] represents the nominated names of the participants’ social other at social distance of N = 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, or 100; [Close N] represents the nominated names of the participants’ social other at social distance of N = 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, or 50, and [Distant N] represents the nominated names of the participants’ social other at all social distances < [Close N].

Participants made a total of 252 decisions across the first-person and third-party social discounting tasks, each involving the seven previously described social distances.

Prior to commencing the study, participants were informed that their payments were linked to their task responses, ensuring that the experiment adhered to ethical standards and avoided any form of deception, meeting the requirements of behavioral economics. Based on their actual choices, participants received 10% of the total from a randomly selected trial. If a participant chose the generous option, the designated person also received 10% of the amount allocated for them. If necessary, participants were asked after the task to provide an email address or phone number for contacting the relevant person to facilitate payment through PayPal or an Amazon gift card. In cases where the randomly selected trial involved a person at a social distance of 100, a random recipient received the payment from our database of future participants.

Participants then completed a battery of moral belief questionnaires to assess explicit moral beliefs in order to evaluate the role of normative moral beliefs in impartial altruism. These included the moral relativism scale (MRS30; a 10-item self-report questionnaire that asks participants to indicate their level of agreement with statements regarding the universality of morality on a 1–5 Likert scale to assess the level of black and white moral thinking regarding right and wrong. Participants also completed the moral tolerance scale (MTS30; a 10-item self-report questionnaire that asks participants to indicate their level of agreement with statements regarding their acceptance of opposing moral views on a 1–5 Likert scale, to assess the level of respect and tolerance granted to differing moral viewpoints. Finally, participants completed the Oxford utilitarianism scale (OUS24; which indexes negative and positive dimensions of utilitarian judgments using 9 items scored on a 7-point scale. The OUS has two subscales, impartial beneficence (impartial maximization of the greater good, even at a personal cost) and instrumental harm (willingness to cause harm to bring about the greater good).

Participants also completed the McGill Friendship Questionnaire Respondent’s Attachment and Friend’s Functions subscales (MFQ-RA; MFQ-FF31), which assess relationship quality between altruists and their closest other, as well as controls and their closest other. The MFQ-RA is a 15-item self-report measure that assesses participants’ perceived levels of satisfaction and positive feelings within a particular friendship, using a −4 to 4 Likert scale. For the purposes of this study, which examines relationships beyond friendships, we tailored the wording of the items, such that “friendship” is replaced by “relationship”. The second subscale of the MFQ, the MFQ-FF, is a 30-item self-report measure that assesses participants’ perceived levels of stimulating companionship, helpfulness, intimacy, reliability, self-validation, and emotional security within a particular friendship, using a 0–8 Likert scale. As with the previous subscale, we revised the verbiage of applicable items to apply to relationships beyond friendship. For more information regarding these self-report measures, see Table S7.

As part of the larger battery, participants also completed a psychopathy questionnaire (TriPM32; a Financial Interdependence scale—asking participants the extent to which they are financially interdependent with their study partner), a Friends of Kidney Donors Questionnaire (asking close other partners of altruists questions regarding their feelings and thoughts about their study partner donating a kidney), and a Kidney Donor Questionnaire (asking altruists their feelings and thoughts they had after donating as well as those they thought their study partner had regarding the donation). The results of these measures are not reported here because they (1) address questions that are outside the scope of this paper and (2) are not attached to any of our preregistered hypotheses. Participants indicated their attention using three attention checks distributed throughout the survey. Finally, participants provided socio-demographic information (including age, gender, race, education, and income).

For analyses using linear models, data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Power and sensitivity analyses

We calculated sample size in G*Power33 based on the social discounting effects published by Vekaria and colleagues9, which features samples of both altruistic kidney donors and demographically-matched controls (Cohen’s d = 0.80, alpha = 0.05, target power = 0.80, computation type = two-tailed comparison of means). The results of this power analysis suggested a total of 26 subjects per group in order to detect an effect of this size (>0.79). We then multiplied this computed sample size by 2 in order to account for the nesting within the model, a recommendation by Aiken and West34 suggested by Schönbrodt et al.35 as appropriate for dyadic analysis. Thus, we aimed to recruit a minimum total of 52 dyads per group, or a total of 208 participants, with a stopping rule (due to funding limitations) of 260 participants.

The study sample included 59 altruists, 59 close others of altruists (nominated by altruists as their closest other), 71 controls, and 71 closest others of controls. Altruists and controls were closely matched in gender distribution and race/ethnicity (see Table 1 for full demographic reports and estimates of statistical power).

A post-hoc sensitivity analysis revealed that for analyses involving multivariate linear regressions, with an alpha level of 0.05 and a power of 0.80 were sensitive enough to detect a small to medium effect size of at least f2 = 0.117, or a beta value of 0.122 or larger.

Modeling first-person and third-party social discounting behavior

Following standard procedures36, we first calculated an “indifference point” for each participant when they transitioned from selecting selfish choices to opting for sharing. In order to include participants with multiple crossover points within a given trial, multiple crossover points were averaged in the data-cleaning process.

Therefore, we obtained “amount willing to forgo” (v) values corresponding to each of the social distance (N) combinations (e.g., self vs. N = 2, N = 10 vs. N = 50, etc.). For our computed measure of social discounting, the area under the curve (AUC) was computed for each participant by normalizing the amount willing to forgo (v) as a percentage of the maximum v, normalizing social distance (N) as a percentage of the maximum N, connecting the crossover points with straight lines, and then summing the areas of the trapezoids formed.

First-person and third-party social discounting reveals higher generosity and impartiality in altruists

AUC is calculated through a trapezoidal function summing the average amounts willing to forgo at each social distance and converting them to a proportion where 0 < AUC < 1, such that an AUC of 0 would indicate that the participant never chose to split resources during that trial block and that an AUC of 1 would indicate that the participant always chose to split resources during the trial block. Therefore, higher AUC values in the first-person social discounting task reflect greater generosity, while higher AUC values in the third-party discounting task indicate greater impartiality.

We replicated the finding that altruists engage in reduced social discounting compared to controls (b[95% CI] = −1.98[−3.06, −0.90], t value = −3.21, df = 703, p < 0.001; see Table S1 in the SI) in the first-person social discounting task9,10.

Using a binomial logistic regression model predicting group membership from AUC, controlling for age, income, and gender, we found altruists were more generous (higher AUC) than controls (OR[95% CI] = 31.78 [6.83, 148.41], z value = 4.41, df = 131, p < 0.001; Table 2). Higher income was also associated with altruism in this model OR[95% CI] = 2.44 [1.65, 3.59], z value = 4.38, df = 131, p < 0.001; Table 2).

We also found that altruists show greater impartiality in our third-party discounting task, sacrificing on behalf of close others to benefit more distant others. We tested this prediction by comparing AUC values from the N = 1 third-party discounting trial, in which participants chose to either allocate money to their closest other (N = 1) or to split money equally between their closest other and a more distant other (Ns = 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, or 100). We conducted a binomial logistic regression model predicting group membership from social discounting rates (AUC), controlling for age, income, and gender. Results indicated that altruists exhibited dramatically more impartial altruism than controls (OR[95% CI] = 23.55 [5.58,99.53], z value = 4.31, df = 130, p < 0.001; see Table 3 and Fig. 2). Income was also associated with altruist status in this model (OR[95% CI] = 2.18 [1.45, 3.29], z value = 3.73, df = 130, p < 0.001).

***P < 0.001. Altruists’ and controls’ first-person social discounting (monetary allocation between self and N = 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100) and third-party social discounting when making decisions for their closest other (monetary allocation between N = 1 and N = 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100). P values from solid line denote significance from logistic regression predicting altruist status from first-person social discounting AUC, controlling for demographic variables. P values from the dashed line denote significance from logistic regression predicting altruist status from third-party AUC from the N = 1 trial, controlling for demographic variables.

We next assessed the social discounting behaviors of altruists and controls when allocating money between all other social distances (e.g., between N = 5 and N = 50, between N = 2 and N = 100, etc.). Results confirmed that altruists exhibited more impartiality, allocating significantly more resources to more distant recipients than did controls in 26 of 28 comparisons (Fig. 3).

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Numerical values represent the average amount ($) that participants elected to give to the more distant social other. Larger (darker) values represent more impartiality (more generosity toward the more distant other). Smaller (lighter) values represent more favoritism for the closer other. P-values derived from two-sided t-tests between altruists and controls.

The effect of favoritism on relationship quality

Our results did not find evidence that heightened impartiality (i.e., reduced favoritism toward close others) in the third-party social discounting task is associated with poorer relationship quality. To assess this, we calculated respondent affection scores from the McGill Friendship questionnaire, as reported by both altruists’ and controls’ close others. This subscale measures satisfaction and positive feelings about a social relationship. Using a linear regression model predicting respondent affection from group membership (altruists, controls), controlling for the age, income, and gender of both dyad partners, we found no statistically significant differences in respondent’s affection across groups (b[95% CI] = −0.29[−0.65, 0.07], t value = −1.57, df = 104, p = 0.121; see Table S2 in the SI). Similar effects were found in a similar model using group membership (altruist, control) to predict friendship function scores from the McGill Friendship questionnaire; this scale indexes feelings of stimulating companionship, helpfulness, intimacy, reliability, self-validation, and emotional security within a social relationship as reported by close others (b[95% CI] = −0.23[−0.71, 0.25], t value = −0.94, df = 104, p = 0.352; see Table S3 in the SI). We employed two separate models to avoid multicollinearity due to high bivariate correlations between these subscales (r = 0.62, df = 222, p < 0.001; Table S4 in the SI).

To assess the direct relationship between impartiality and relationship quality, two additional linear models were run, predicting altruists’ and controls’ close others’ (1) respondent affection and (2) friendship function from altruists’ and controls’ third-party social discounting scores (AUC) from their N = 1 trials, where they made partial or impartial decisions regarding their closest other. These models similarly controlled for age, income, and gender, and similarly failed to find any statistically significant predictors of relationship quality in either model (brespondent_affection [95% CI] = −0.02 [−0.54,0.50], t value = −0.09, df = 102, p = 0.928; bfriendship_function [95% CI] = −0.03 [1−0.71, 0.66], t value = −0.08, df = 102, p = 0.933; Tables S5, S6 in the SI). For Bayesian analyses of these group comparisons, see ‘Deviations from Preregistration’ below.

Homophily in impartiality

In light of these findings, we tested the prediction that altruists would show altruistic homophily: that is, their closest friends and family members would also be more generous toward distant others than would controls’ closest friends and family members. To test this prediction, we conducted a binomial logistic regression predicting group membership (partners of altruists, partners of controls as baseline) from social discounting rates, controlling for age, income, and gender, and found close others of altruists were also more generous than controls’ close others (OR[95% CI] = 4.22 [1.14, 15.68], z value = 2.15, df = 113, p = 0.031; see Table 4 and Fig. 4), such that for every 0.1 increase in AUC (where values range from 0 to 1) the odds of being the close other of an altruist is 3.22 times higher. Again, income was also associated with altruist status in this model (OR[95% CI] = 1.80 [1.29, 2.51], z value = 3.43, df = 113, p < 0.001; Table 4).

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. First-person social discounting (monetary allocation between self and N = 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100) across all four groups.

Predictors of impartiality

We next tested alternative potential mechanisms that prior research suggests may drive altruists’ impartiality. One potential mechanism is heightened concern for impartial beneficence. Another related mechanism is that this heightened concern is a normative or prescriptive moral conviction, such that altruists are more impartial in the third-party task due to reduced moral tolerance or sense of moral relativism for competing, partial moral values (such as ingroup favoritism). Another (not mutually exclusive) mechanism is consensus bias, or the implicit view that others share one’s own beliefs and preferences26 such as a preference for impartiality and sharing resources with distant others. If this phenomenon were driving altruists’ decisions, we would predict first-person social discounting decisions to predict allocation decisions in the third-party task. To test the role of these factors, we conducted a three-step hierarchical regression model predicting altruists’ N = 1 discounting from altruists’ own social discounting for self (Step 1), their utilitarian beliefs (Oxford Utilitarianism Scale; Step 2), and their moral tolerance and moral relativism (Moral Relativism Scale and Moral Tolerance Scale; Step 3), controlling for age, gender, and income throughout. At each step, altruists’ first-person social discounting was the sole predictor of third-party discounting decisions, predicting impartiality toward study partner above and beyond moral beliefs at Step 1 (b[95% CI] = 0.73 [0.50, 0.96], t value = 6.28, df = 52, p < 0.001; Table 5), Step 2 (b[95% CI] = 0.71 [0.47, 0.95], t value = 5.90, df = 50, p < 0.001; Table 5), and Step 3 (b[95% CI] = 0.70 [0.45, 0.95], z value = 5.66, df = 48, p < 0.001; Table 5). This suggests altruists make similar choices on behalf of their close others as they would make for themselves, and this pattern is not related to explicitly held moral beliefs as measured here.

Deviations from preregistration

In our preregistration (https://osf.io/g7xc6/), we planned to use hyperbolic models (logk) to detect group differences in the first-person and third-party tasks. Logk is typically used interchangeably with area-under-the curve (AUC) to analyze first-person social discounting tasks, and these measures typically yield highly correlated results37,38,39. Logk modeling utilizes the following equations:

Level 1 (hyperbolic function):

The model assessed how discounting rates (logki) varied among altruists compared to controls:

Unfortunately, we determined comparisons between first-person generosity and third-party impartiality are infeasible using hyperbolic modeling due to the fact that decisions begin at N = 1 in the first-person task and at N = 2 in the third-party task. Comparing slopes with different starting points on the x-axis is not conceptually valid. Thus, we used AUC for all analyses. AUC, which is model-agnostic, allows comparisons of actual participant data as opposed to predicted values from hyperbolic, predictive models, which is preferable for a task with unknown response patterns prior to this study. AUC also captures both the starting point and the shape of the discounting curve and thus can differentiate between selfish and generous responses when discounting rates are similar38.

We also conducted two Bayesian analyses that were not pre-registered to compare the alternative hypothesis (group differences between altruists and controls in relationship satisfaction as measured by the MFQ-FF and the MFQ-RA) against the null hypothesis (no group differences). The Bayes factors for the alternative hypotheses (r = 0.707) were BF10 = 0.372 (± 0.02%) for the MFQ-FF and BF10 = 0.239 (±0.03%) for the MFQ-RA. This indicates that the MFQ-FF data are ~0.37 times as likely under the alternative hypothesis as under the null hypothesis and that the MFQ-FF data are ~0.24 times as likely under the alternative hypothesis as under the null hypothesis. Hence, results for MFQ-FF provide anecdotal evidence for the null hypothesis and the results for MFQ-RA provide moderate evidence for the null hypothesis40.

Discussion

Through the use and validation of our third-party social discounting task that directly assessed veridical impartial altruism in real-world extraordinary altruists, we find that these individuals indeed show more impartial altruism compared to controls. When offered the opportunity to allocate actual resources to a close other or to divide them equally between a close and more distant other, they were more likely to divide the resources equally than were typical adults.

Modifying the first-person social discounting paradigm for third-party decision-making allows for a direct behavioral measure of impartiality using participants’ own social networks and employing real-world payouts in order to extend an otherwise hypothetical decision into a task with tangible outcomes. Previous measures of (im)partiality have relied on self-reported Likert responses, such as the fairness/reciprocity and ingroup/loyalty foundations in the moral foundations questionnaire41,42 or relied on self-reported levels of concern for different entities, as in the moral expansiveness scale43. Though useful, these scales do not directly assess behavior or real-world outcomes. Meanwhile, studies linking impartial versus partial altruism to anticipated relationship quality do so via third-party judgments of hypothetical characters3,6,7. By contrast, participants in our third-party social discounting task made decisions that resulted in real-world payouts to actual others in their social networks based on their decisions. Responses in this third-party social discounting task followed the hyperbolic decay of the first-person social discounting paradigm, validating that variation in social distance predicts generosity when respondents choose how to allocate resources between two individuals in their social network (as opposed to choices simply reflecting selfish versus selfless tradeoffs, as is portrayed in the class social discounting task)8.

Prior work suggests such impartial generosity might conflict with the favoritism and prosocial prioritization of close others usually associated with close relationships and undermine the quality of these relationships3,6. But using two measures of impartial altruism–real-world altruistic kidney donation and increased impartiality in the third-party social discounting task–our results indicate that the propensity for impartial altruism need not come at the cost of the quality of close relationships. In the present study, relationship satisfaction for highly impartial participants was not significantly lower than that of controls, who showed relatively more favoritism for their close others. This may be due to value homophily, as altruists’ close others also showed low levels of social discounting (were similarly generous and for distant relatives to close others). In light of prior findings that only relatively impartial participants do not view impartial altruists as worse relationship partners7, this suggests similar levels of generosity and impartiality within close relationships may serve as a protective factor for highly impartial, altruistic individuals to maintain high levels of relationship satisfaction with similar close others. By the same token, controls and their close others exhibited similarly lower levels of impartial altruism. This underscores our findings related to the mechanisms underlying impartial altruism. We found that first-person social discounting decisions predicted impartial altruism. These results are consistent with consensus bias—that altruists may implicitly respond on others’ behalf as they would on their own behalf. Importantly, however, the accumulated patterns contradict a false consensus bias, as altruists’ decisions appear to correctly reflect how their close others would actually respond.

We did not find that explicit beliefs about impartiality or morality predict impartial altruism. Participants completed measures of normative moral beliefs to assess whether impartiality reflects explicit beliefs about impartial beneficence24, moral tolerance (respect for moral priorities that differ from one’s own), or low moral relativism (impartial decisions for others based on the belief that the value of impartiality should be applied to all). However, none of these belief frameworks were significant predictors of impartial altruism. Although past work has found impartial beneficence to predict extraordinary, selfless altruism13, the present study’s findings corroborate the presence of a moral judgment-behavior gap44, perhaps because moral judgments and self-reported moral values lack some of the salient moral features, external pressures, and other context relevant for real-world moral decisions and actions.

At face value, our findings might seem to contradict past work in moral psychology in which impartial characters are viewed as worse relationship partners3,6,7. The finding that third-party character judgments do not corroborate real-life reports of relationship quality could reflect the effects of salience bias on judgments in such scenarios, including moral judgments45. Salience bias is the tendency to over-inflate the importance of salient information simply because it is more noticeable or prominent than more relevant, less salient factors46,47,48,49. This discrepancy might also be partially due to the sample at hand. The close others of altruists were not the random or convenience samples used in many moral judgment studies but were the closest friends or family members of a highly impartial person. These relationships have been selected and maintained over time. People who view altruists’ impartiality unfavorably may be less likely to form or maintain close relationships with them.

Our results suggest a reason that altruism may not come at the cost of close relationship quality is value homophily–the phenomenon of preferential formation and maintenance of close relationships with those who share similar values, attitudes, and beliefs16,17,19,20. Though altruists were less partial toward their closest others compared to controls, the closest others of altruists were similarly less partial and more generous when compared to the closest others of controls. Similar values have been found to benefit cooperation17, and moreover, similar levels of cooperative behavior have been found to extend to up to two degrees of separation50. Yet how value homophily influences close relationship quality has remained an open question. More, value homophily provides insight into why such impartial altruism does not negatively affect close relationships. Rather than one party viewing impartiality favorably and the other party viewing impartiality negatively, our dyadic data suggests that patterns of generous decision-making are similar within dyads. That close others respond similarly during the discounting task aligns with a growing body of neuroscience findings that social closeness predicts similarity in how people respond to events in the world at neural level51. Future work should seek to investigate the causes of value homophily in close relationships. Although close relationships research suggests similarity in close relationships results from selection effects rather than partners becoming more similar over time52, altruism research suggests that altruistic behavior and preferences can be socially contagious53,54. Future work should also investigate how more distant, less relationally satisfied dyads vary (or do not vary) in impartiality, generosity, and other values, as including a more diverse range of relationships might reduce ceiling effects in relationship satisfaction scores.

Limitations

Our findings should be considered in light of some limitations. One limitation is that efforts to recruit controls who were demographically similar to altruists resulted in a sample that was relatively racially and ethnically homogenous and on average, richer and more educated than the average American. This, in part, reflects the selection criteria applied to living kidney donors, who must typically meet stringent health criteria before donating, including low risk for kidney disease, which disproportionately affects lower-income, Black, and Hispanic adults in the United States. However, it is reasonable to assume our findings would apply to more demographically representative samples, as prior research has found that more diverse altruistic samples, such as bone marrow donors and heroic rescuers10,55,56, display similar reductions in first-person social discounting as altruistic kidney donors10 as well as other similar personality and behavioral traits. It is also worth noting that income was associated with altruist status in our models. This is likely due to sampling, as controls were, on average, lower income in our sample (see Table 1). This group difference is consistent with prior work showing reliable positive associations between altruism and various measures of objective and subjective well-being, including wealth (Rhoads and Marsh57). It could be argued that the behavior of altruists in this study may reflect their awareness that they were recruited for a study on altruism, introducing an experimental demand bias. Several pieces of evidence argue against this possibility. First, altruists do not score highly on self-report altruism or empathy scales more directly related to altruism and more susceptible to demand effects10,58. Second, prior work finds that the traits and behaviors that most reliably distinguish altruists from controls are not those predicted by the average person, suggesting that altruists are not simply conforming to stereotype-consistent behaviors10. Prior behavioral and neuroimaging work also find no evidence that altruists’ reduced social discounting reflects effortfully overcoming selfishness. Instead, neural activation during the task in regions that include amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex correspond to the subjective valuation of others’ welfare predicted by the social discounting model12. Lastly, the task’s real-world payout component further reduces demand effects, as participants were aware that their decisions were yoked to real money.

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings address fundamental questions regarding the potential real-world social costs of impartial altruism. We used our behavioral paradigm to veridically model impartial altruistic decisions in real-world altruists and controls, along with their closest friends and family members. We found that impartial altruists tend to have impartial friends and family members, and similar close relationship quality as controls. This study contradicts prevalent beliefs that care for others is limited in quantity, a belief associated with reduced empathy and caring behaviors toward distant others59. Rather, we find that altruism toward socially distant others need not prevent impartial altruists from enjoying the benefits of close social relationships.

Responses