Co-cultivation of high-value microalgae species with filamentous microalgae for dairy wastewater treatment

Introduction

Microalgae have several notable advantages, including rapid growth, the ability to fix carbon dioxide, its potential as a biofuel feedstock, and the capability to synthesize various valuable products1,2. Ongoing endeavors aim to use microalgae for applications in fuels, cosmetics, chemicals, food, and feed. Despite these efforts, the large-scale production of microalgae is constrained by high cultivation costs and the substantial energy required for biomass harvesting. Studies indicate that the cost of microalgae production ranges from €36/kg to €105/kg of biomass, with harvesting costs typically accounting for 20−30% of the total production costs3.

Recently, using wastewater for microalgae cultivation has attracted significant attention due to its potential to reduce freshwater requirements by up to 90%, which makes this method more sustainable and cost-effective than traditional approaches that rely on freshwater and supplemental nutrients4,5,6,7,8.

More than 12% of the total agricultural output in the European Union (EU) comes from the dairy sector, making it the second-largest agricultural sector in the EU9. The high production of dairy products also results in the generation of substantial amounts of dairy wastewater (DW). Annually, EU-27 countries generate around 192.5 million cubic meters of DW10. According to the European Dairy Association, wastewater generated by the dairy industry results from several rinsing processes, including pre-rinsing, inter-rinsing, and clean-in-place operations11. DW is typically treated using physico-chemical methods like coagulation and flocculation, membrane filtration, sedimentation, electrocoagulation, and adsorption, which require substantial amounts of chemicals, energy, and operating expenses. Conventional biological treatments, including anaerobic and aerobic processes, or combinations of physico-chemical and biological methods, are also commonly employed. While these methods are effective, they often produce sludge that requires additional management and disposal, increasing environmental and economic challenges. Additionally, they tend to consume large amounts of energy10. In contrast, microalgae-based treatment presents a more sustainable option. Microalgae can assimilate organic pollutants and convert them into valuable cellular components, such as carbohydrates and lipids, reducing pollutants in an eco-friendly manner. This approach also has the added potential of exploiting the biomass produced, making it an attractive option compared to traditional processes1. Therefore, utilizing DW for the cultivation of microalgae and its simultaneous remediation has been reported in literature7,12. However, on a large scale, maintaining the axenicity of microalgae culture for wastewater treatment is not feasible due to the high cost of the aseptic process and its limited capacity to uptake nutrients and generate carbohydrate/lipid-rich biomass13. Therefore, to develop an efficient and economically feasible wastewater treatment process, the use of microalgae consortia instead of monoculture can be a feasible solution that can tackle the contamination risk (due to the production of allelochemicals), can enhance nutrient removal efficiencies (due to co-operative interactions) and hence generate valuable biomass13. Therefore, the current study focuses on the development of microalgae consortia consisting of high-value microalgae sp. and filamentous microalgae for the treatment of DW and generation of valuable biomass.

The harvesting of microalgal biomass poses a considerable obstacle, primarily due to several inherent characteristics of microalgae. These include their microscopic size (1−10 µm), a density that closely matches that of water, a negative surface charge (−7.5 to −40 mV), and a slow settling rate (10−5−10−6 m s−1)14. Commonly employed methods for biomass harvesting include centrifugation, filtration, sedimentation, and the use of organic and inorganic flocculants1. However, each method has its drawbacks; centrifugation is highly energy-intensive, sedimentation is a slow and time-consuming process, and the use of flocculants requires removal from the culture medium before reuse, incurring additional operational costs1. The utilization of microalgae consortia comprising microalgae along with bioflocculants like bacteria or fungi has been explored for wastewater treatment and biomass harvesting15,16. Nevertheless, introducing fungi or bacteria into microalgal cultures poses a contamination risk that could negatively affect the growth and productivity of desired microalgal sp.17. Hence, bioflocculation of non-flocculating microalgae sp. with flocculating filamentous microalgae sp. appears to be a viable strategy to enhance harvesting efficiency17,18. These filamentous microalgae act as bio-flocculants, capturing small-sized microalgae cells within their filamentous networks, thereby forming large, dense biomass aggregates17. This bio-flocculation process facilitates the easy harvesting of microalgal biomass through simple gravitational sedimentation or filtration1,17. Compared to harvesting single-sp. cultures, the mixed consortium approach reduces the energy and cost required for biomass recovery, making the overall process more economical. One study reported a harvesting efficiency of 64.9‒88.5% during the cultivation of microalgae consortia consisting of filamentous Tribonema sp. with Chlorella zofingiensis in swine wastewater18. Furthermore, the presence of both non-flocculating and flocculating filamentous sp. enhances the overall biomass yield, providing more material for harvesting18.

Existing literature predominantly focuses on the utilization of microalgae consortia for the treatment of DW to produce biodiesel feedstock12,19. However, no study to date has developed microalgae consortia comprising non-flocculating microalgae sp. along with flocculating filamentous microalgae sp. for the remediation of DW, enhancement of harvesting efficiency, and generation of valuable biomass. Therefore, the present study aims to develop microalgae consortia consisting of non-flocculating microalgae sp. C. vulgaris and Scenedesmus sp. in combination with flocculating filamentous microalgae sp. Tribonema and Lyngbya sp. The objectives will be pursued through (a) assessing different combinations of non-flocculating with flocculating filamentous microalgae sp. for biomass production and DW remediation, (b) investigating the effect of harvesting time on the accumulation of biochemical components in monoculture and consortia, and (c) evaluating the harvesting potential of monoculture and microalgae consortia.

Results

Biomass growth profile of monoculture and microalgae consortia grown in dairy wastewater

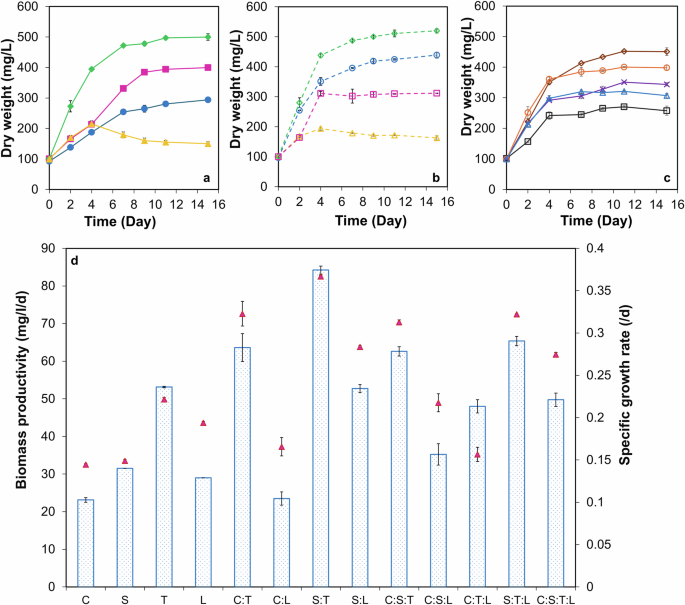

The biomass growth profile of monoculture and microalgae consortia grown in DW are shown in Fig. 1a–c. From Fig. 1, co-culturing microalgae sp. C. and S. with filamentous microalgae sp. T. increased the biomass growth by 13‒53% as compared to what was obtained with C. and S. alone (p < 0.05). Further, the biomass productivity (BP) and the specific growth rate increased by 12‒174% compared to the BP obtained with monoculture (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1d). All the combinations of C. and S. with T. performed well in the order S:T (520 ± 7.07 mg L−1) > C:S:T (451 ± 12.72 mg L−1) > C:T (439 ± 9.89 mg L−1) as compared to the combinations tested with L (Fig. 1). This may be because L. itself did not grow very well and entered into the decline phase after day 4. Therefore, the growth in the consortia of C:L, S:L, C:S:L, C:T:L, S:T:L, and C:S:T:L is mainly contributed by the other sp. present in the consortia. From Fig. 1a and b, the maximum biomass growth of 520 ± 7.07 mg L−1 obtained with consortia S:T was significantly similar (p > 0.05) to biomass growth of 500 ± 10.6 mg L−1 obtained with T. However, the maximum BP of 84.25 ± 1.06 mg L−1 d−1 and the specific growth rate of 0.37 ± 0.01 d−1 obtained with consortia S:T were 58‒167% higher than what was obtained with S. and T. alone (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1d).

a Monocultures: a closed green diamond with a solid green line refers to Tribonema sp., a closed pink square with a solid pink line refers to Scenedesmus sp., a closed blue circle with a solid blue line refers to Chlorella vulgaris, a closed yellow triangle with a solid yellow line refers to Lyngbya sp. b Consortia (1:1): an open green diamond with a green dotted line refers to consortia S:T, an open blue circle with a blue dotted line refers to consortia C:T, an open pink square with a pink dotted line refers to consortia S: L, an open yellow triangle with a yellow dotted line refers to consortia C: L. c Consortia (1:1:1, 1:1:1:1): an open brown diamond with a solid brown line refers to consortia C:S:T, an open orange circle with a solid orange line refers to consortia S:T:L, purple cross with a solid purple line refers to consortia C:T:L, an open blue triangle with a solid blue line refers to consortia C:S:T: L, an open black square with a solid black line refers to consortia C:S:L. d Biomass productivity and specific growth rate of monoculture and microalgae consortia: blue column refers to biomass productivity, a closed red triangle refers to the specific growth rate. The values are the mean of two replicates (n = 2) with standard deviation.

Removal of COD, NO3

−-N, and PO4

3–-P from dairy wastewater by monoculture and microalgae consortia

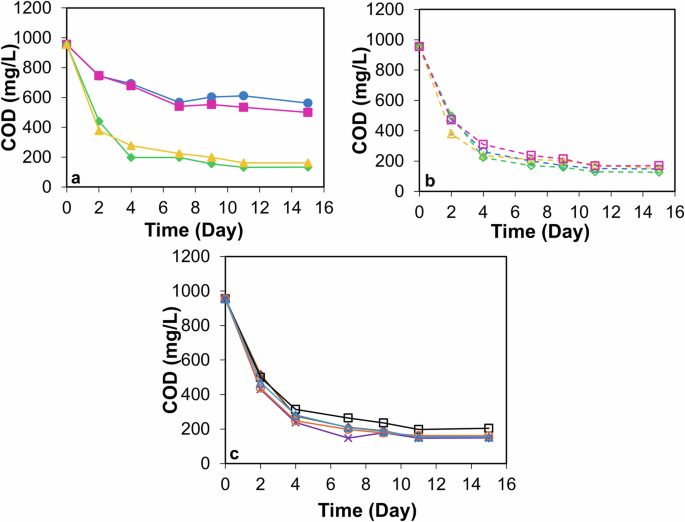

The removal profile of COD from DW by monoculture and microalgae consortia is shown in Fig. 2. From Fig. 2a, microalgae sp. C. and S. showed COD removal of 41% (net reduction: 393 mg L−1) and 47% (net reduction: 455 mg L−1), respectively. However, significant enhancement in COD removal percentage was obtained with microalgae consortia (p < 0.05). The range of COD removal obtained with microalgae consortia was 79−88% (net reduction: 750−828 mg L−1) (Fig. 2b and c). This may be due to the synergistic effects between the different types of microalgae. Also, as can be seen from Fig. 2a, the filamentous microalgae sp. T. and L. played a major role in COD removal which was 86% (net reduction: 821 mg L−1) and 83% (net reduction: 793 mg L−1), respectively.

a Monocultures: a closed green diamond with a solid green line refers to Tribonema sp., a closed pink square with a solid pink line refers to Scenedesmus sp., a closed blue circle with a solid blue line refers to Chlorella vulgaris, a closed yellow triangle with a solid yellow line refers to Lyngbya sp. b Consortia (1:1): an open green diamond with a green dotted line refers to consortia S: T, an open blue circle with a blue dotted line refers to consortia C:T, an open pink square with a pink dotted line refers to consortia S: L, an open yellow triangle with a yellow dotted line refers to consortia C:L.. c Consortia (1: 1: 1, 1: 1: 1: 1): an open brown diamond with a solid brown line refers to consortia C:S:T, an open orange circle with a solid orange line refers to consortia S:T:L, purple cross with a solid purple line refers to consortia C:T:L, an open blue triangle with a solid blue line refers to consortia C:S:T:L, an open black square with a solid black line refers to consortia C:S:L.

The removal profiles of PO43–-P and NO3−-N from DW by monoculture and microalgae consortia are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. From Table 1, 92‒96% of PO43–-P was removed from DW within 4 days. This high removal efficiency indicates that the microalgae were highly effective in assimilating PO43––P from the DW quickly. By the end of 15th day, PO43–-P values were below the detection limit (<0.05 mg L−1) in DW for all monocultures and consortia except for S:T:L. Table 2 shows that most of the NO3−–N was removed from DW within 2 days, with values falling below the detection limit for all (<1 mg L−1), except L. and the consortia having L., which had NO3−-N values of 1.5‒2.6 mg L−1. However, by the 4th day, NO3−-N values were below the detection limit (<1 mg L−1) in DW for all monocultures and consortia.

Biochemical composition of monoculture and microalgae consortia grown in dairy wastewater

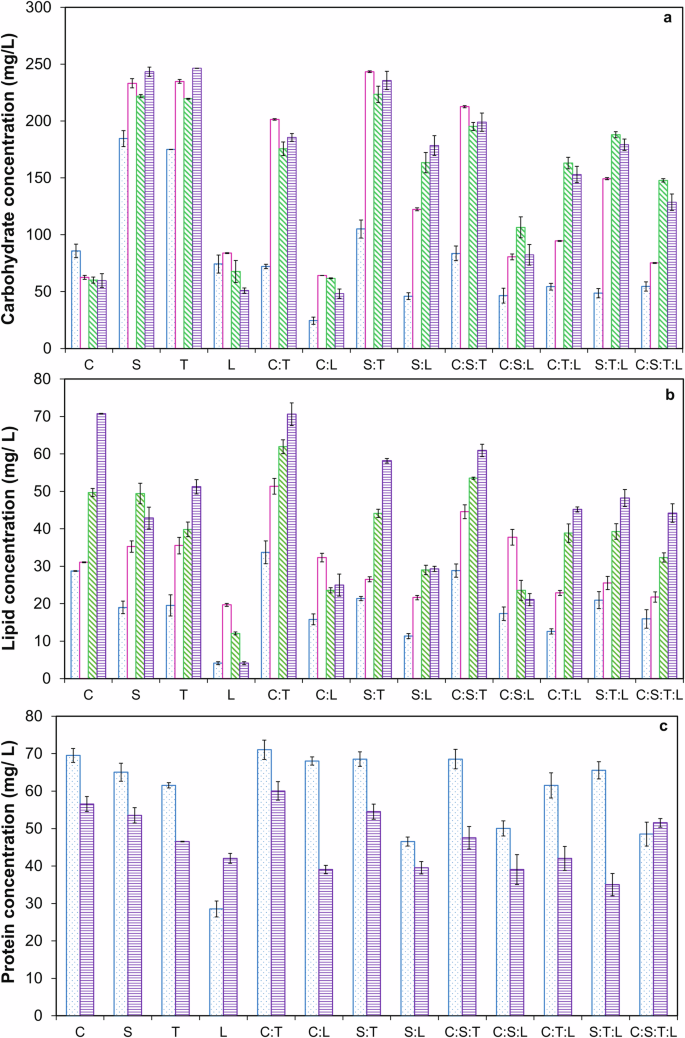

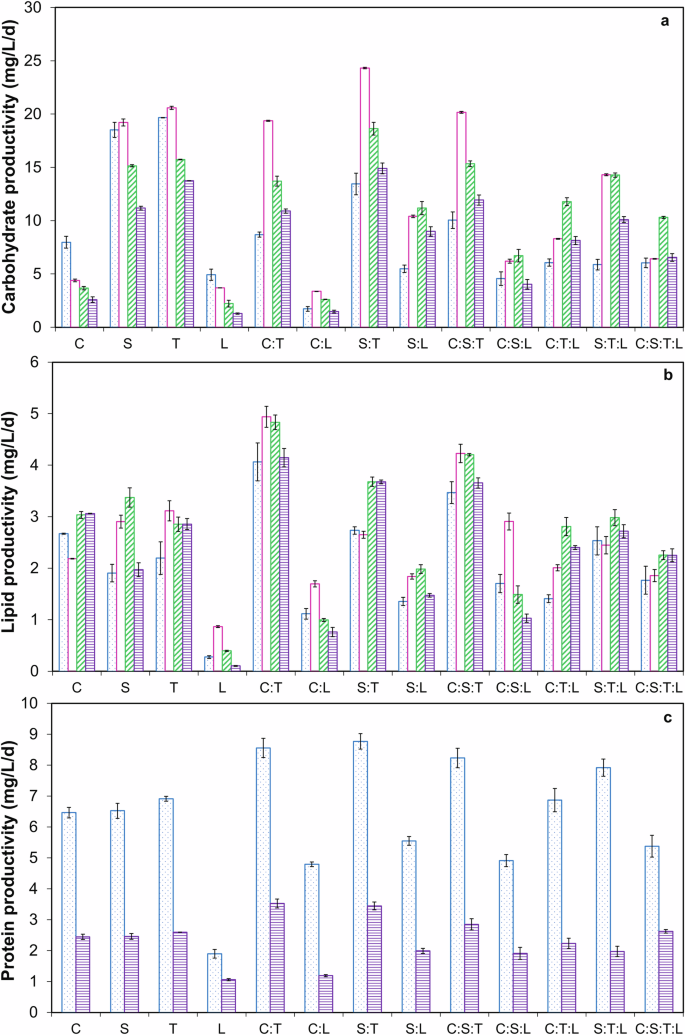

The biochemical compositions, including concentrations, productivities, and contents (%) of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins for monocultures and microalgae consortia grown in DW, are shown in Figs. 3 and 4, and Table 3. Carbohydrate and lipid concentrations increased by 31.8‒268.3% from day 7 to day 15, while protein concentrations decreased by 15‒46.5% during the same period (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3c). However, the maximum carbohydrate productivity (CP) and lipid productivity (LP) were obtained on day 9. Co-culturing microalgae sp. significantly reduced the time required to achieve the maximum carbohydrate concentration. Specifically, the time decreased from 15 days to 9 days when co-culturing, as the maximum carbohydrate concentration of 246.5 ± 0.07 mg L−1 achieved by T. on day 15 was nearly the same as that of the consortia S:T on day 9 (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3a). Moreover, the consortia S:T exhibited a maximum CP of 24.31 ± 0.07 mg L−1 d−1 on day 9, which was 26.55% and 18.15% higher than the productivities of S. and T. monocultures, respectively (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, the carbohydrate content of 54.84% for the S:T consortia on day 9 was comparable to that obtained on day 15 (Table 3).

a Carbohydrate concentration. b Lipid concentration. c Protein concentration. The blue column refers to day 7, the pink column refers to day 9, the green column refers to day 11, and the purple column refers to day 15. The values are the mean of two replicates (n = 2) with standard deviation.

a Carbohydrate productivity. b Lipid productivity. c Protein productivity. The blue column refers to day 7, the pink column refers to day 9, the green column refers to day 11, and the purple column refers to day 15. The values are the mean of two replicates (n = 2) with standard deviation.

Regarding lipid production, prolonged exposure to nutrient limitation increased lipid concentration and content (%) from day 7 to day 15 as a protective mechanism20 (Fig. 3b and Table 3). The maximum lipid concentration of 70.8 ± 0.09 mg L−1 achieved by C. on day 15 was similar to that obtained for the consortia C: T (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3b). However, LP decreased from day 9 to day 15, with the maximum LP of 4.94 ± 0.2 mg L−1 d−1 obtained on day 9 for consortia C: T which was significantly higher by 126.03% and 58.63% compared to C. and T. monocultures, respectively (Fig. 4b). Protein concentrations, productivities, and contents (%), decreased by 15–75% from day 7 to day 15 (p < 0.05) (Figs. 3c, 4c, and Table 3).

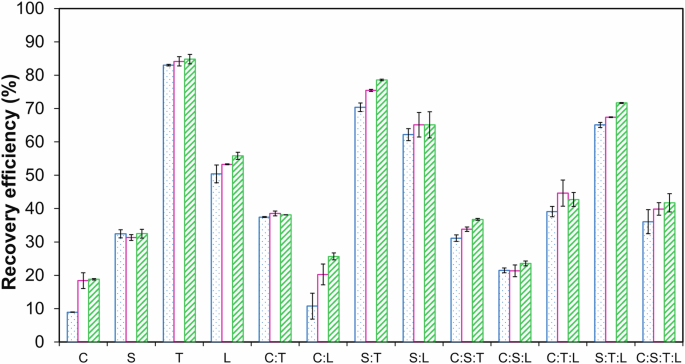

Harvesting potential of monoculture and microalgae consortia grown in dairy wastewater

The study investigated the biomass recovery of various microalgae sp. from DW at the end of day 15 over a period of 3 h, and the results are shown in Fig. 5. The focus was on both, monocultures and consortia of microalgae sp., examining how flocculating and non-flocculating sp. performed individually and in combination. In the case of monocultures, the microalgae C. and S. showed biomass recoveries of only 18.82 ± 0.21% and 32.48 ± 1.31%, respectively, within 3 hours. In contrast, the microalgae sp. T. and L. exhibited high biomass recoveries of 84.8 ± 1.39% and 55.8 ± 1.06%, respectively, within 3 h. Consortia containing non-flocculating sp. C. or S. along with flocculating sp. T. or L. showed significantly higher biomass recovery (25.66‒78.54%) compared to monocultures of C. or S. alone (p < 0.05). The highest biomass recovery of 78.54 ± 0.24% was obtained for the consortium S: T, comparable to the 84.8 ± 1.39% recovery of the monoculture T. This suggests that the flocculating species T. was highly effective in co-flocculating and harvesting the non-flocculating species S. when grown together. The consortium C:L and C:S:L exhibited low biomass recovery of 25.66 ± 1.03% and 23.54 ± 0.75%, respectively, potentially because species L did not thrive well in DW (Fig. 1), resulting in insufficient biomass to effectively trap C. and S. cells, slowing the settling process.

The blue column refers to 1 h, the pink column refers to 2 h, and the green column refers to 3 h. The values are the mean of two replicates (n = 2) with standard deviation.

Discussions

The study reveals that co-culturing different microalgae species in a consortium significantly increases biomass production, which may be due to the functional richness and diversity within the community. When microalgae sp. are co-cultivated, they can exhibit complementary metabolic and enzymatic activities, which can enhance environmental adaptability and result in higher biomass growth compared to monocultures21. Qin et al. also reported 14.6% increase in biomass growth during the cultivation of microalgae consortia (C. sp. and C. zofingiensis) in DW as compared to the biomass growth achieved with C. sp. only12. The growth in the consortia containing L. is mainly contributed by the other sp. present in the consortia. The reason could be that DW may have an imbalance of nutrients that are essential for the growth of L. The nutrient concentrations, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, may favor other microalgae species over L. Further, the current study used microalgae sp. C. and S., which are often used for wastewater treatment5,6,8,18. However, in the current study, these two strains grew slower than filamentous microalgae T. This may be due to the different nutritional requirements of different microalgae sp. Moreover, the most conducive consortia S:T, reach their exponential growth phase faster than the monoculture, resulting in higher BP and growth rates, even though S:T and T. eventually reach similar total biomass production. Similar findings of achieving almost the same biomass growth but with a higher BP for a consortium of T. and C. zofingiensis, compared to that obtained for its monoculture in anaerobically digested swine wastewater, were also reported by Cheng et al.18. The enhanced biomass productivity observed in the co-cultivation system compared to monocultures might be attributed to potential synergistic interactions between the two species. These interactions likely stimulate each other’s growth by enhancing metabolic activities and optimizing nutrient utilization. Additionally, co-cultivation may increase the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs), presumably as a result of the enhanced sp. interactions. EPSs can stabilize the culture by forming a protective matrix and facilitating nutrient exchange, thereby supporting the growth of both microalgae and filamentous microalgae22,23. These mechanisms potentially explain the enhanced biomass productivity in co-cultivation systems, though further research is needed to confirm their exact roles and influences. Future studies could employ metabolomic analysis to identify key exchanged metabolites or use gene expression profiling to understand how co-cultivation affects metabolic pathways in each species.

The maximum biomass growth obtained in this study with consortia S:T was 520 ± 7.07 mg L−1 which is in line with the reported study in the literature for DW: 450 mg L−1 with consortia of C. vulgaris, Nannochloropsis oceanica, and Tetradesmus obliquus24, 673 mg L−1 with consortia of C. variabilis, and S. obliquus25, 470 mg L−1 with S. quadricauda26, 430 mg L−1 with S. quadricauda27. However, another study reported higher biomass growth of 2500 mg L−1 with microalgae consortia (S. abundans, Nostoc muscorum, and Spirulina sp.) as compared to biomass growth of 600−800 mg L−1 with its monoculture19. The reason for this may be the nutritional composition of DW. The DW used by Chandra et al. had a high concentration of nitrogen (105 mg L−1) and phosphorus (36 mg L−1). Therefore, it can be said that microalgae growth is highly dependent on the initial characteristics of the wastewater medium used for cultivation.

The study found that microalgae consortia achieved higher COD removal from DW compared to C. and S. monocultures, with filamentous microalgae playing a significant role in this COD removal (Fig. 2). The higher COD removal with filamentous microalgae sp. T. compared to C., and S. could be due to the higher biomass production of filamentous microalgae, which can lead to higher COD removal. However, despite the higher COD removal efficiency, the biomass production was lower with filamentous microalgae L. This could be due to the lower growth rate and biomass yield of L. compared to C. and S. Additionally, filamentous microalgae L. may require more nutrients to grow, which could limit their biomass production. The nearly complete removal of PO43–-P within 15 days, with most occurring within the first four days, highlights the effectiveness of microalgae in PO43–-P uptake and potential applications in bioremediation (Table 1). The rapid reduction of NO3−-N within two days for most cultures and complete removal by the fourth day underscores the algae’s capability to assimilate NO3−-N efficiently (Table 2). However, the initial slower reduction in NO3−-N levels by L. and consortia containing L. suggests that different species or combinations may vary in their NO3−-N assimilation rates. The rapid consumption of PO43–-P and NO3−-N from DW observed in this study aligns with findings reported by Biswas et al.28. The study reported initial values of 9 mg L−1 and 5.5 mg L−1 for phosphate and nitrate, respectively, in bacterially treated DW. These nutrients were rapidly consumed by an algae-bacteria consortia, with concentrations dropping below the detection limit within 48 hours. Further, the COD, nitrogen, and phosphorus removal obtained in this study is in line with the reported studies for DW, as can be seen in Table 412,19,25,28,29,30.

The observed increase in carbohydrates and lipids, along with the decrease in protein suggests a strategic metabolic shift induced by nutrient limitation, which prompts microalgae to accumulate storage compounds (carbohydrates and lipids) instead of proteins31,32. The reduction in time to reach maximum carbohydrate concentration and achieving almost similar carbohydrate content (%) in co-cultures (from 15 days to 9 days) demonstrates the efficiency of co-culturing in enhancing productivity. A similar observation of achieving nearly identical carbohydrate content on day 15 and day 21 during the cultivation of A. dimorphus in synthetic media was reported in a study33. The results showing higher LP with consortia compared to monocultures are consistent with previous studies that reported similar synergistic effects in mixed cultures12,19. The possible mechanisms behind the higher biochemical productivity in a co-cultivation system, compared to monocultures, may be linked to mutualistic interactions between sp. These interactions could potentially enhance each other’s growth, leading to improved metabolic activities associated with the biosynthesis of key biochemical components. Additionally, microalgae naturally produce EPSs, and in co-cultures, the increased interactions between species may result in higher EPS production. This potential boost in EPSs could provide metabolic support, possibly aiding growth and promoting the accumulation of carbohydrates and lipids, particularly under nutrient-limited conditions22,23. The superior performance of the S:T consortia in terms of BP and harvesting efficiency highlights its potential as an optimal choice for maximizing yield and efficiency in DW remediation (Figs. 1d and 5). While day 9 was optimal for CP, day 11 was better for LP, suggesting that different biochemical goals require specific harvesting times (Fig. 4). This study confirms that microalgal consortia can significantly outperform monocultures in terms of productivity and that optimizing harvesting times is essential to maximize yields of valuable biochemical components in minimal cultivation periods.

The study found low biomass recovery of C. and S. is due to the lack of self-flocculation or auto-flocculation ability in these sp., which keeps the cells suspended in the culture medium. However, higher biomass recovery of T. and L. is attributed to their inherent ability to auto-flocculate or self-flocculate, leading to rapid settling and harvesting of the biomass. Further, the high biomass recovery in consortia is likely due to the flocculating species (T. or L.) inducing co-flocculation or entrapping the non-flocculating cells within the flocs, facilitating their settling and harvesting. Studies have shown that microalgae flocculation can significantly enhance biomass recovery. Flocculating species produce extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that promote cell aggregation, leading to efficient sedimentation17,18. Cheng et al. reported only 34.7% recovery of C. zofingiensis biomass; however, biomass recovery increased from 64.9‒88.5% when C. zofingiensis was co-cultivated with T18. The success of microalgae growth and subsequent biomass recovery depends on the compatibility of species with the growth medium. Species that do not thrive well in specific conditions (like L. in DW) will not contribute effectively to biomass recovery in consortia. The study demonstrates the advantages of using flocculating microalgae and their combinations with non-flocculating sp. to enhance biomass recovery. The findings highlight the need to consider species-specific growth conditions and interactions when designing microalgae consortia for optimal biomass harvesting.

Using dairy wastewater for the co-cultivation of microalgae with filamentous algae presents promising opportunities for sustainable biomass production, as the wastewater provides a rich nutrient source. However, scaling this approach for industrial applications poses several challenges that need to be carefully addressed for success:

-

Variability in wastewater composition: Dairy wastewater composition can vary significantly due to seasonality, production practices, and cleaning processes. Fluctuations in nutrient levels, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon, can make it difficult to maintain optimal conditions for both microalgae and filamentous algae. Additionally, the nutrient ratios may not always align with the requirements of both algae types. Periods of nutrient deficiency or excess can reduce BP and destabilize the system. Optimizing nutrient balance is crucial for maximizing biomass yield.

-

Environmental and operational challenges at scale: Scaling the co-cultivation system for industrial use introduces environmental challenges such as fluctuations in light intensity, temperature, and pH. These inconsistencies may also result from insufficient stirring, leading to uneven conditions within the culture medium. Such fluctuations create a more heterogeneous environment, complicating large-scale implementation. Additionally, scaling up may require significant energy input for mixing, aeration, and possibly artificial lighting, which increases operational costs and may reduce the economic feasibility of the system. Furthermore, the financial success of this approach depends on the value of the final biomass products. Relying solely on biofuels may not generate enough revenue to cover the costs of large-scale treatment, harvesting, and processing. so exploring higher-value products such as bio-based chemicals might be necessary.

-

Product consistency: Ensuring consistent quality and composition of the biomass, such as carbohydrate, lipid, and protein content, is critical for industrial applications. Co-cultivation systems may introduce variability in the final biomass composition, especially if one species dominates at different times. This variability can make it difficult to meet industry standards for specific products, requiring additional monitoring and adjustments to maintain consistent product quality.

Methods

Microalgae species

Chlorella vulgaris (NIVA-CHL 108), Scenedesmus sp. (NIVA-CHL 116), Tribonema sp. (NIVA-1/84), and Lyngbya sp. (NIVA-CYA 455) were purchased from Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA), Oslo, Norway. The microalgae culture was maintained and cultivated in 250 mL conical flasks containing 150 mL sterilized BG11 media. The flasks were kept in a shaking incubator containing light under the following cultivation conditions: irradiance−5800 lx; temperature—22 °C; light:dark cycle—12 h:12 h.

Characterization of the wastewaters

The raw DW was obtained from a dairy industry in Norway. The wastewater was stored at 4 °C and kept for 72 h to let the suspended solids settle down. The wastewater was sterilized in an autoclave and analyzed for physicochemical parameters, the values of the same are presented in Table 5.

Experimental procedure

The pH of the DW was adjusted to 7.0 before conducting the experimental runs. For the experiment, a 500 mL culture of well-grown microalgae species was centrifuged for 15 min at 4500 rpm and then the microalgae suspension was washed thrice using sterilized distilled water. For the monoculture study, all four microalgae culture was inoculated into the wastewater with the initial concentration of 0.1 g L−1. For the consortia study, 9 combinations of microalgae sp. were tested at the ratio of 1:1 for two species, 1:1:1 for three species, and 1:1:1:1 for four species with the initial concentration of microalgae 0.1 g L−1 in all runs. The present study conducted a total of 13 runs, as shown in Table 6 for 15 days. The cultivation conditions were similar to those used for the cultivation of microalgae sp. The study also tested the effect of harvesting time on biochemical compositions of monoculture microalgae sp. and microalgae consortia by withdrawing the culture on days 7, 9, 11, and 15.

During the experimental runs, samples were withdrawn periodically and centrifuged for 15 min at 4500 rpm. The supernatant was analyzed for COD, NO3-N, and PO43–-P. The pellet was used to determine dry weight, carbohydrate, lipid, and protein content of microalgae sp. All the experimental analysis were carried out in duplicate.

Microalgae growth determination

To measure dry weight, a 10 mL sample was centrifuged, and the microalgae pellet obtained after centrifugation was washed and filtered using GF/C filter paper. The- filter papers were then dried in a hot air oven at 105 °C until a constant weight was achieved. The biomass productivity (mg L−1 d−1) and specific growth rate (d−1) were determined during the exponential phase using Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

where X1 and X2: dry weight of monoculture and consortia (mg L−1) at time t1 and t2 (day), respectively.

Chemical oxygen demand, nitrate, and phosphate analysis

For the determination of wastewater parameters, 10 mL samples were withdrawn periodically and centrifuged for 15 min at 4500 rpm. The supernatant was analyzed for COD, NO3−-N, and PO43–-P using a Spectroquant test kit based on the Photometric method. Removal percentage and removal rates of COD, NO3−-N, and PO43–-P was analyzed using following equation:

where S0 and S1: Initial and final concentrations of the wastewater parameter, respectively; t1 and t2: initial and final time, respectively.

Determination of biochemical composition of microalgae species

For the determination of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, a 1 ml sample was withdrawn on days 7, 9, 11, and 15 for each analysis and centrifuged. The supernatant was then removed, and the pellet was washed three times with sterilized distilled water. For total carbohydrate estimation, the phenol sulfuric acid method was used34,35. For lipid estimation, the sulfo-phospho vanillin method was used36. For protein estimation, the Bradford method was used34,37. The protein estimation was performed on days 7 and 15 only. The content (%) and productivity (mg L−1 d−1) of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, were determined using Eqs. (4) and (5), respectively.

Determination of harvesting potential of microalgae consortia

To check the harvesting potential of microalgae consortia, at the end day, i.e. day 15, the sample was withdrawn at different time intervals, i.e., 0, 1, 2, and 3 h, and measured optical density (OD750 nm) using Spectroquant. Harvesting efficiency (%) was determined by using the following Eq. (6):

where OD750 (t0) and OD750 (t): turbidity of the sample taken at 0 h and at time t, respectively14,15.

Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the differences among the mean values, with subsequent analysis performed using a Tukey post hoc test in Minitab 18 software. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Responses