Coastal wetland resilience through local, regional and global conservation

Introduction

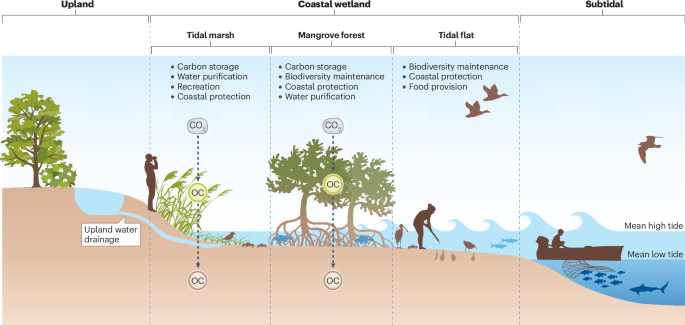

In the world’s most densely populated coastal zones between land and ocean, coastal wetlands, which include tidal marshes, mangrove forests and tidal flats, support the well-being of millions of people1. In addition to forming nursery habitats for numerous juvenile fishes and exporting organic matter to subsidize offshore waters2 (Fig. 1), coastal wetlands also support biodiversity by providing habitats for many unique or threatened plant and animal species3. As long as they are protected by a sufficiently large wave-attenuating tidal flat4, tidal marshes and mangrove forests attenuate destructive storms, purify wastewater runoff, prevent shoreline erosion and sequester carbon (blue carbon) at rates orders of magnitude higher than those of terrestrial forests and grasslands5,6,7. Provisioning of these services ranks coastal wetlands among the most valuable ecosystems on Earth8.

Upland boundaries for tidal marshes and mangrove forests are limited by competition from other vascular plants, and lower boundaries (typically at the mean high water of neap tides) by drowning and sediment anoxia. Carbon storage occurs, in part, via sequestration of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere as organic carbon (OC) in plant and substrate organic matter. Coastal wetlands are ecosystems of major value to humanity in multiple different ways, ranging from recreation (such as bird watching) to food provision. We note that many services are found in all types of coastal wetland and that only a representative few are shown for each type of wetland.

Coastal wetlands are threatened by an increasing number and intensity of anthropogenic impacts. In addition to local anthropogenic threats to coastal wetlands (such as wetland reclamation for agriculture and aquaculture), coastal wetlands are also affected by anthropogenic threats from adjacent ecosystems within a region (such as watershed pollution and nearshore fishing)9,10, as well as threats operating at global scales including elevated temperatures and sea-level rise (SLR) driven by global climate change11,12,13. Loss of coastal wetlands has reduced the populations of fisheries and endangered shorebirds14, increased carbon emissions15,16, and increased risk to human infrastructure and life from storms and floods7,17. Over the past several decades, conservation efforts targeting sustainable development and the harmonious coexistence of humanity and nature in coastal zones have been increasing18,19,20. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted by 196 nations in 2022 has set global targets to protect at least 30% of coastal ecosystems, and to restore at least 30% of those degraded by 2030. Achieving these conservation targets necessitates the development of effective strategies to enhance the resilience of coastal wetlands21,22.

Despite increased research attention11,23,24,25, the resilience of coastal wetlands to anthropogenic threats, especially those operating at regional and global scales, has yet to be fully understood. Physical processes, such as sediment supply and hydrology, have been increasingly recognized as important drivers of coastal wetland resilience26,27,28. Coastal wetlands are also strongly regulated by ecological processes, such as biotic and biophysical interactions, which contribute, positively or negatively, to their resilience29,30,31. For example, plants in tidal marshes and mangrove forests can accelerate sediment deposition, lowering the depth and duration of water inundation and enabling these ecosystems to persist when facing SLR32. Although decisions on conservation actions could be highly context-dependent, a collective synthesis of the drivers of coastal wetland resilience is critical for informing effective actions by conservation practitioners and policy makers to meet conservation targets.

In this Review, we synthesize anthropogenic threats to coastal wetlands and the drivers of their resilience through the lens of scale, focusing on tidal marshes, mangrove forests, and tidal flats. Except where noted, we omit tidal swamps which remain poorly studied compared to other types of coastal wetlands33,34. First, we briefly review the distributions of coastal wetlands and their biodiversity. Second, we identify anthropogenic threats to the extent and quality of coastal wetlands across local, regional and global scales. Third, we examine the drivers of coastal wetland resilience across different scales, highlighting that resilience is fundamentally driven by the quality of coastal wetlands. From this multiscale understanding of anthropogenic threats to coastal wetlands and the drivers of their resilience, we outline future conservation priorities to enhance both the extent and quality of coastal wetlands at relevant scales.

Distributions and biodiversity

Understanding the distributions of coastal wetlands and their biodiversity is essential for developing spatial conservation planning35. Local and regional information about the distribution of coastal wetlands and associated biodiversity has been available for many decades, but advances in remote sensing now facilitate the study of global patterns (Box 1). In this section, we first review the current distributions of coastal wetlands and then highlight the diversity and spatial variation of plant, animal and microbial species occupying these habitats.

Current distributions

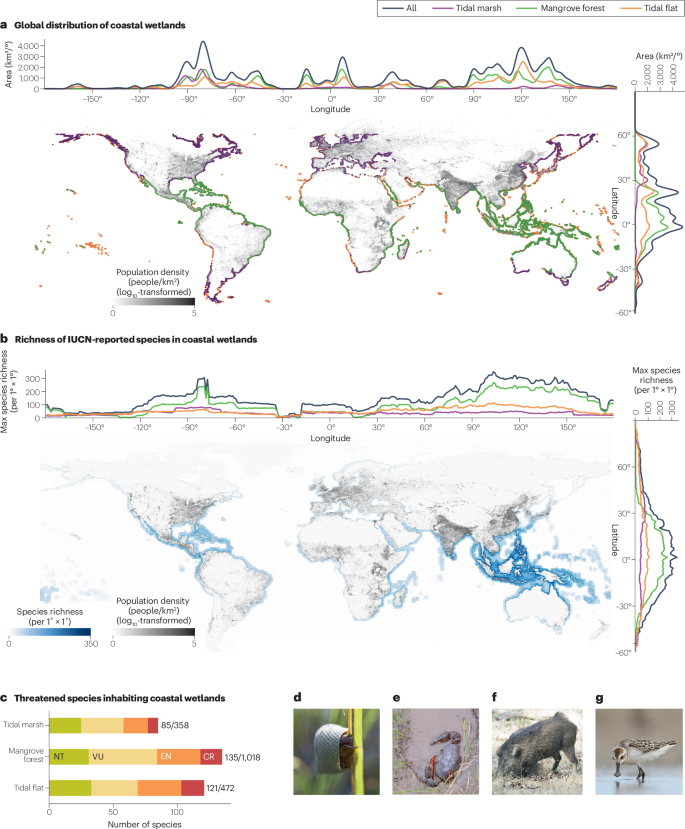

The global mapping efforts of coastal wetlands36,37 indicate that in 2019–2020, 354,600–355,120 km2 of coastal wetlands are distributed from the densely populated tropical shores of Java to the cold, unpopulated coastlines of Siberia (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Table 1). Globally, mangrove forests cover the widest area (145,068–157,250 km2), followed by tidal flats (122,960–140,923 km2) and tidal marshes (52,880–90,800 km2; Supplementary Table 1). The Northern Hemisphere has approximately twice as many coastal wetlands as the Southern Hemisphere, reflecting the much longer coastlines in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 2a). By latitude, mangrove forests are found in tropical and subtropical zones between 30° N and 30° S. Tidal marshes are mainly found at latitudes higher than 25° N and 15° S, though they can be found in the tropics. By contrast, tidal flats are broadly distributed in all climatic zones, and extensive tidal flats are even found in polar zones above 60° N (ref. 37). Longitudinally, tidal marshes, mangrove forests and tidal flats all peak around 80° W and 120° E, where tropical and warm temperate coastlines are particularly extensive, shallow and complex, with myriad bays and islands, as in the Caribbean and southeast Asia (Fig. 2a).

a, Global distribution of tidal marshes, mangrove forests and tidal flats alongside human population density. Areas above 60° N and S are data-deficient owing to limited high-quality remote-sensing images. b, Global distribution of species richness for species inhabiting tidal marshes, mangrove forests and tidal flats, based on the ICUN Red List of Threatened Species. c, Number of threatened species inhabiting tidal marshes, mangrove forests and tidal flats on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Numbers adjacent to a bar indicate the number of threatened and near-threatened species divided by the total number of species reported (including species labelled as least concern and data deficient). Photographs in d to g depict representative common and threatened species inhabiting coastal wetland ecosystems. d, Periwinkle snails (Littorina littorea), which graze and facilitate pathogenic fungi on plant leaves. e, Mud crab (Scylla serrata), a keystone predator in coastal wetlands in East Asia. f, Feral hog (Sus scrofa), an invasive mammal in the southeastern USA. g, Spoon-billed sandpiper (Calidris pygmaea), a critically endangered shorebird. CR, critically endangered; EN, endangered; NT, near-threatened; VU, vulnerable. Both the global distribution of coastal wetlands and their species richness are concentrated in tropical regions, which often have high human population density (also see ref. 207). The coastal wetland distribution data in panel a are from refs. 177,208,209, the human population data in panels a and b are from ref. 204, and the species data in panels b and c are from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Photograph credit: panels d and e, Qiang He; panel f, reprinted from https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/159409844 (Daniel S. Katz, iNaturalist Network), CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/); panel g, Tengyi Chen.

Indonesia, the USA, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, China, Nigeria, India and Myanmar have the largest total area of all coastal wetlands combined (Table 1; see Supplementary Table 2 for a list of the top ten countries or regions with the largest tidal marshes, mangrove forests and tidal flats). Coastal zones are generally densely populated38 (Fig. 2a) and many of the countries or regions with the largest area of coastal wetlands (such as China, Nigeria, India and Myanmar) have a coastal population density even higher than the global average population density in coastal zones (224 people per square kilometre; Table 1). Furthermore, many of these countries or regions still face intense development pressures, with a coastal gross domestic product per capita lower than the global coastal average (18,734 international dollars; Table 1). This combination of high human population densities and strong demand for economic growth in coastal zones puts substantial anthropogenic pressure on coastal wetlands.

Associated biodiversity

Coastal wetlands harbour unique biodiversity adapted to the often salty, frequently flooded transitional habitats between land and ocean. Plant species diversity is generally low in coastal wetlands (the species diversity of algae, such as those on tidal flats, has been less studied). For example, only about 70 mangrove species have been identified globally39 and in most tidal marshes, only one or a few plant species are found per square metre40. However, many of these plant species (such as Spartina alterniflora, Scirpus mariqueter and most mangrove species) are found predominantly in coastal wetlands, sometimes with considerable intraspecific genetic diversity. In tidal marshes on Sapelo Island, Georgia, USA, for example, 74 unique multilocus genotypes of Borrichia frutescens were identified and 447 unique multilocus genotypes of S. alterniflora were identified out of 480 ramets per species41. In mangrove forests on the northern Pacific coast of Nicaragua, the mean number of alleles per locus per population was 6.42 for the red mangrove Rhizophora mangle42.

Plants serve as the foundation species that define these coastal wetland ecosystems, and in turn support a high diversity of faunal species of certain taxonomic groups, including birds, fishes and aquatic invertebrates such as crustaceans and molluscs12. Coastal wetlands in the Yellow Sea provide stopover habitats for millions of shorebirds across 60 species that migrate along the East Asian–Australasian Flyway43. Tidal marshes in Queensland, Australia provide feeding grounds for 23 fish species44. Globally, tidal marshes and mangrove forests support at least 84 fully and semi-aquatic megafauna species that include sea turtles, dolphins, porpoises, otters, mink, seals, crocodiles, alligators, dugongs, manatees, sharks and rays45.

The diversity of microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, fungi and viruses) has also been increasingly explored in the past few decades. In a tidal flat in China, for example, 1,911 operational taxonomic units of viruses were found in sediment samples46. As of 2021, a total of 486 taxa of fungi have been recorded in tidal marshes globally47.

Notably, many of the plant and animal species inhabiting coastal wetlands are considered threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Although not yet comprehensive, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is an authoritative, widely used data source that is currently available for global-scale analyses of biodiversity. Of the 1,589 species attributed to these ecosystems and assessed by the IUCN, 17% are threatened or near-threatened. Proportions of threatened species are particularly high for mammals (71%) and chondrichthyans (sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras; 83%). Of the same 1,589 species, 24.1%, 13.2% and 25.6% of the assessed 358, 1,018 and 472 species occupying tidal marshes, mangrove forests and tidal flats are threatened or near-threatened, respectively (Fig. 2c).

The biodiversity of coastal wetlands is variable across space, often mirroring patterns in the extent of coastal wetlands. Traversing the vertical elevation gradient of a spatially restricted wetland site will reveal that different plants and animals, sessile species in particular, often dominate different tidal zones and exhibit striking zonation patterns48,49. With increasing elevation, species of terrestrial origin such as plants50 and insects51 typically increase in number, whereas those of marine origin such as fishes, crustaceans and molluscs44,52 typically decrease. Salinity is especially variable in estuaries, and plant and animal occurrence can also change strikingly along a salinity gradient, with glycophytes (plants that grow in non-saline soils) dominating tidal freshwater wetlands in the upper reaches of estuaries, away from more saline ocean waters53,54.

At large scales, the overall species richness of plants and animals is generally greater at lower latitudes than higher latitudes, at least among the 1,416 plant and animal species with reported geographic ranges encompassing coastal wetland habitats on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (most of them are species associated with mangrove forests) (Fig. 2b). Similar latitudinal patterns in species richness are also found in specific groups of species and in regional studies, such as mangroves55, fishes56, megafauna45 and nematodes57, although the species richness of tidal marsh plants58, shorebirds3 and bacteria59 can peak in temperate regions. Across longitudes, the overall species richness of plants and animals in coastal wetlands peaks around 80° W and 120° E (Fig. 2b). Regional and global-scale patterns of coastal wetland biodiversity, however, remain unstudied for many taxa. A detailed study of regional and global biodiversity requires extensive data collection and analysis, including field surveys and taxonomic identification. Advances in molecular sequencing approaches (including DNA metabarcoding and environmental DNA) and species distribution modelling techniques are contributing to exploration of these gaps in our knowledge.

Anthropogenic threats

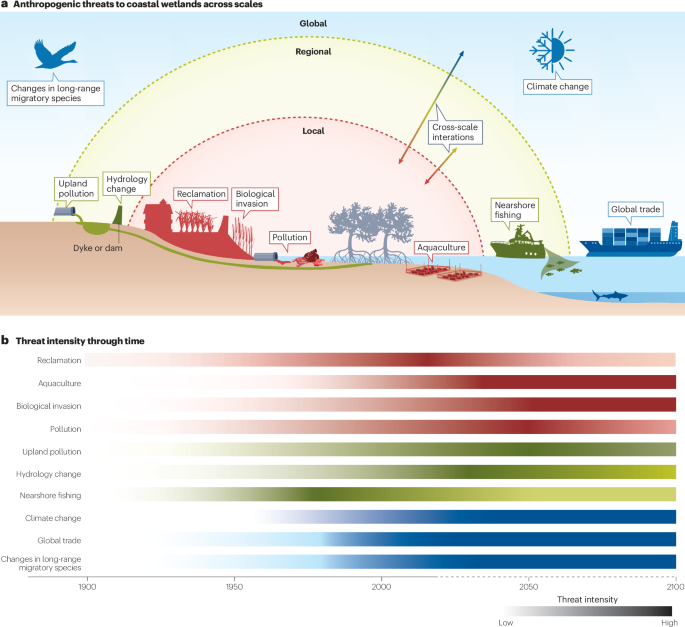

Over the past several decades to centuries, anthropogenic threats to coastal wetlands have expanded from localized human disturbances to pervasive impacts arising from a combination of local, regional and global stressors (Fig. 3; reviewed in refs. 12,13,60,61,62,63). Here, we highlight predominant anthropogenic threats to the extent (such as reclamation) and quality (such as species invasions) of coastal wetlands at local, regional and global scales. We refer to an anthropogenic threat as affecting the extent or quality of coastal wetlands according to its primary effect, which can also vary depending on the magnitude of the threat.

a, Schematic of anthropogenic threats at local (red), regional (yellow) and global (blue) scales, including cross-scale interactions. b, Historical and future trends in the intensity of the anthropogenic threats at local, regional and global scales. The dotted part of the x axis indicates future projections. The threats to coastal wetlands are complex and interactive. Whereas some anthropogenic threats (such as reclamation and nearshore fishing) have begun to decrease, many others (such as aquaculture, biological invasions and climate change) are likely to intensify under future scenarios.

Local threats

Coastal wetlands have been directly affected by local human activities for millennia (Fig. 3a), with their extent being directly reduced by conversion for agriculture, aquaculture and urban use. The Mesopotamian tidal marshes in southwest Asia are thought to be the birthplace of agriculture64. Reclamation of coastal wetlands — including tidal flats — for croplands, aquaculture farms and urban areas began in the Roman Empire, accelerated between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, and is probably the single largest cause of contemporary coastal wetland loss in Europe and globally65.

Coastal wetland quality is also threatened by many local human activities, including fishing, bait digging, livestock grazing and plant harvesting. Fishing and livestock grazing date to the Neolithic in the coastal wetlands bordering the North and Wadden seas66,67, and coastal wetlands have long been used as a dumping ground for sewage and trash in populated areas, probably since the Middle Ages68. The introduction of alien or invasive species, such as S. alterniflora, native to the US eastern and Gulf coasts, often results in loss of native wetland plants or tidal flat habitats that could be of particular importance, such as for migratory shorebirds69,70,71. Although many local threats to coastal wetland extent are now controlled in some regions19,20,72, threats to the quality of coastal wetlands remain severe or may even intensify in the future, including light, noise and plastic pollution73,74,75 (Fig. 3b).

Regional threats

At larger scales, anthropogenic activities taking place in adjacent wetland or non-wetland ecosystems within a region can threaten coastal wetlands (Fig. 3). A key regional threat to the extent of coastal wetlands is modifying hydrology. Restriction or interference with tidal seawater exchange can reduce the extent of coastal wetlands owing to changes in hydrological conditions, such as tidal infiltration and sediment starvation76,77. Similarly, the diversion of freshwater through artificial barriers, such as dams, can considerably reduce the flow of water and sediments, as well as organisms, reaching coastal wetlands78.

Regional threats can also affect coastal wetland quality. One such threat stems from land-use or sea-use changes in the landscape or seascape. Conversion of uplands into impervious surfaces, such as buildings and parking areas, can increase the diffusion of nutrients and sediments to coastal wetlands via watershed. Although increased sediments can help to build coastal wetlands, eutrophication can disrupt the balance of production away from structurally important roots and towards growth of shoots, resulting in shoreline destabilization9,79. Excessive nutrients can also favour invasive species and increase the abundance of species competing with native species80,81. Conversion of offshore waters for aquaculture might not only increase nutrient loading in coastal wetlands82,83, but can also lead to loss of adjacent deeper-water habitat-forming species, such as oysters, seagrasses or corals, thereby exacerbating the exposure of coastal wetlands to waves and storms84,85. Coastal wetland quality is further threatened by exploitation of species that migrate or disperse across the landscape or seascape. Fishing-driven loss of aquatic predators that migrate between nearshore waters and tidal marshes, for example, can release herbivorous crabs and snails in tidal marshes from predator control86,87. Unregulated herbivore population growth and runaway grazing can suppress or denude marsh vegetation86,87. Although many species migrate or disperse across the landscape or seascape and are exploited outside their coastal wetland habitats88, the cascading consequences of their exploitation have often been neglected as regional threats.

Global threats

At global scales, coastal wetlands have been, and are likely to be, increasingly threatened by global climate changes, such as warming, SLR and more intensive and frequent extreme climate events, and by anthropogenic activities that alter the flow or movement of non-living materials and organisms across distant regions (Fig. 3).

The extent of coastal wetlands can be threatened by global climate change. SLR, for example, is the most pervasive global threat to the extent of coastal wetlands, given that they typically occupy narrow intertidal elevation bands24. In places where suspended sediment concentrations are low and accretion cannot match SLR, the seaward limits of tidal marsh plants and mangroves will retreat because of increasing stress from drowning32. If global warming exceeds 2 °C above preindustrial levels (before 1850–1900) and the rate of global mean SLR increases to 7.8 mm per year in 2080–2100 (ref. 89), models project that nearly all the world’s mangrove forests and 40% of mapped tidal marshes will fail to cope with the SLR and will eventually drown25. The loss of tidal marshes and mangrove forests with SLR could initially lead to increases in the extent of tidal flats, although SLR above a certain threshold (such as a relative SLR of 4–10.5 mm per year for Ameland Inlet in the Dutch Wadden Sea90,91) might ultimately convert tidal flats into constantly inundated subtidal areas. Furthermore, although some aspects of global climate change can have positive effects (for example, warming allows poleward expansion of tidal marshes92,93,94), extreme climate events (including those occurring in unusual seasons) often result in loss of coastal wetlands. Extreme heat and droughts can contribute to the mortality of wetland plants, resulting in the loss of mangrove forests and tidal marshes and conversion to tidal flats95,96,97,98,99. Stronger storms driven by a changing climate can also increase tidal flat erosion100.

The quality of coastal wetlands can also be threatened by global climate change, as well as by anthropogenic activities that affect the connectivity between coastal wetlands and distant systems. Instead of causing plant mortality, low-to-intermediate levels of droughts driven by decreased precipitation generally reduce plant growth. Ocean acidification following the Industrial Revolution increases physiological stress on bivalves, gastropods and microalgal coccolithophores101,102 and dissolution of calcareous skeletons. As an example of anthropogenic activities that affect the connectivity between coastal wetlands and distant systems, agricultural intensification in the midwestern USA promoted an overabundance of snow geese (Anser caerulescens), which migrated to and subsequently increased damage to subarctic tidal marshes relative to previous years103,104. Coastal wetlands are habitats for numerous migratory species105,106, whose population dynamics, as with those of snow geese, could be subsidized or inhibited in systems distant from a focal coastal wetland site. Long-range, cross-continental atmospheric transport of pollutants can also decrease the quality of coastal wetlands, including mercury, which threatens fishes and other wildlife in coastal wetlands107,108. Global trade can affect coastal wetlands by increasing the exploitation of natural resources109 and by facilitating invasions of exotic organisms110. In the modern globalizing era, interactions between distant locations have become increasingly widespread, with potentially substantial, but largely understudied, consequences111,112.

Cross-scale interactions among threats

Local, regional and global threats might occur concurrently or sequentially over periods of days to decades, and interact additively, synergistically or antagonistically, to affect the extent and quality of coastal wetlands. Upland conversion to developed areas, for example, constrains the landward migration of coastal wetlands that occurs with SLR, hastening coastal wetland loss and leading to coastal squeeze24. Importantly, threats that impair the quality of coastal wetlands can affect their resilience to withstand other threats. Watershed nutrient input, for example, can decrease the below-ground biomass of bank-stabilizing roots, thereby accelerating the loss of tidal marshes in the face of SLR and strong storms9,113. Watershed sediment runoff can enhance coastal wetland accretion, thereby reducing the loss of coastal wetlands in the face of SLR and strong storms114. Restricting tidal flow can weaken the recovery of native plants in human-trampled tidal marshes and promote the invasion of non-native upland plants115. Reducing threats at one scale, such as local threats, can therefore affect resilience to threats at another scale, such as global threats including SLR13. Although interactions among threats at either local or global scales have been increasingly studied, cross-scale interactions remain largely unstudied.

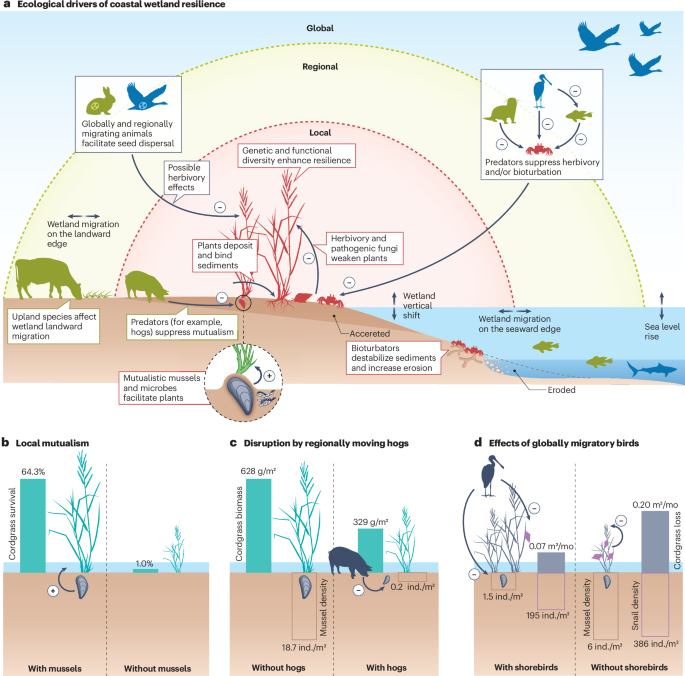

Drivers of resilience

Intensifying anthropogenic threats across local, regional and global scales make it increasingly necessary to understand the resilience of coastal wetlands to anthropogenic threats. The resilience of coastal wetlands is determined fundamentally by their quality and can be modified (increased or decreased) by physical and ecological factors that operate at local, regional and global scales (Fig. 4a). The roles of physical factors (such as sediment supply, hydrology and topography) have been widely studied26,28,116. The effect of ecological factors can be profound31,32 but remains relatively understudied, especially at regional and global scales. Here we first clarify the definition of resilience and then review existing studies (dominated by tidal marsh studies from North America) to identify the drivers of coastal wetland resilience, focusing on their ecological drivers at different spatial scales.

a, Local (red), regional (yellow) and global (blue) ecological drivers of coastal wetland resilience in a representative tidal marsh. b, A mutualistic relationship between mussels and cordgrass facilitates the survival of cordgrass during droughts. c, Regionally moving hogs disrupt mutualistic relationships by consuming mussels, thereby disabling plant–mussel mutualism and weakening the biomass recovery of cordgrass from drought. d, Globally migrating shorebirds can affect the resistance or recovery of cordgrass, but their net effect depends on the balance of their effects on both cordgrass-mutualist species (such as mussels) and cordgrass grazers (such as snails). Shorebirds might consume mussels and/or transmit parasites to grazers. Consuming mussels decreases resistance, but weakening snail herbivory activities via parasite transmission enhances resistance. Coastal wetland resilience is subject to complex drivers that occur at local, regional and global scales, including mutualistic relationships between resident species that could be altered by regionally and globally moving species. Ind., individuals. Data in panel b are from ref. 134, data in panel c are from ref. 30, and data in panel d are from ref. 165.

Defining and assessing resilience

Following historic21 and modern definitions22, we consider resilience to integrate resistance and recovery. Thus, resilience to acute threats (such as pulse disturbances like storms and heat waves) is determined by the capacity to reduce the threat impact (resistance) and subsequently return to the baseline before the threat (recovery). Resilience to longer-term, more diffuse threats (press disturbances such as species invasions and SLR) might be determined more by resistance because negligible time is available for recovery. When exposed to the same level of threat, a coastal wetland is more resilient than another if the threat impact relative to the baseline before the threat is lower, if recovery rate is greater, or if the time needed to achieve recovery is shorter22. Resilience of coastal wetlands can be measured by changes in wetland extent and quality, in terms of species composition and ecosystem functions.

Coastal wetlands often show resilience to certain levels of anthropogenic threats across all scales. Some coastal wetlands change gradually and continuously with increasing levels of anthropogenic threats. However, above a threshold threat level (in other words, a tipping point), coastal wetlands can undergo sudden, abrupt transitions into a degraded state, and exhibit little natural (unaided) recovery117,118. For example, tidal marshes can maintain their spatial extent or expand into uplands with increasing rates of relative SLR if their vertical accretion matches relative SLR. However, beyond a threshold rate of relative SLR of 5–7 mm per year25, vertical sediment accretion cannot keep pace with relative SLR, and tidal marshes will drown as a result of increasing depth and duration of inundation.

Local drivers

At local scales, the resilience of coastal wetlands is affected by a suite of physical and ecological drivers. Resilience to SLR is affected by physical factors such as tidal regime, tidal range, elevation relative to sea level and topography. Resilience to SLR could be greater in one coastal wetland rather than in another if certain conditions are met: if tides are semi-diurnal rather than less frequent, diurnal tides28; if mean tidal range is greater owing to the larger swathe of upper intertidal zone and relatively smaller expansion in tidal prism116; or if elevation relative to sea level is higher, providing greater elevation capital to cope with SLR119. The resilience of coastal wetlands to storms can also be affected by wetland topography. Tidally restricted mangrove forests, for example, are less resilient to storms than unrestricted ones, possibly owing to poor drainage of rainwater120. Physical factors can also affect the resilience of coastal wetlands to local and regional anthropogenic threats. For example, tidal connectivity can decrease the resilience of tidal flats to exotic plant invasions, as interconnected tidal channels facilitate dispersal of exotic plant propagules such as seeds and rhizomes121.

A key ecological driver of coastal wetland resilience at local scales is biological diversity120. High plant species diversity, for example, can promote belowground biomass and their resilience. In Essex, UK, the rate of tidal marsh erosion due to waves and currents was lower when plant species richness was higher122, but — as previously mentioned — coastal wetlands are usually dominated by just a few plant species. Despite fairly low plant taxonomic diversity, the genetic and functional diversity of coastal wetland plants can be high. These levels of diversity can impart resilience through mechanisms including the portfolio effect, where plants resistant to one or more threats maintain ecosystem functioning until other plants recover123,124 (Fig. 4a). The role of genetic diversity in enhancing resilience can be altered by rapid evolution, which might change contemporary ecosystem dynamics125, or by evolutionary rescue, which enables diminished populations to recover and adapt to new environmental conditions126. For example, decadal-scale trait evolution related to soil accretion in the dominant sedge Schoenoplectus americanus over the past 100 years has decreased the resilience of North American tidal marshes to SLR by making root growth shallower and lowering sediment accretion125. In contrast to plants, animal species diversity is frequently high in coastal wetlands (partly because such wetlands can support both terrestrial and marine taxa depending on tidal inundation) and helps to mediate the resilience of coastal wetlands to eutrophication and erosion127. In three New Zealand estuaries, for example, the rate of tidal flat erosion increased with increasing macrofaunal species richness, although it increased more strongly with the abundance of small bioturbating macrofauna128. More studies, particularly those that employ manipulative experiments, are needed to better understand how faunal diversity affects coastal wetland resilience.

Another local ecological driver of coastal wetland resilience is interaction among resident species, including keystone species with roles in structuring ecosystems that are disproportionately large relative to their abundance129. Positive species interactions, including plant–plant130, plant–fungal131 and animal–plant132 interactions and multispecies facilitation cascades133, have been reported to enhance coastal wetland resilience to anthropogenic threats. Ribbed mussels (Geukensia demissa), for example, form mounds that enhance water storage, reduce soil salt stress, filter suspended particles from the water column and transform them into nutrients available to plants, and enhance sediment microbial processes (such as microbial oxidization of ammonium to nitrite and then nitrate134,135). Ribbed mussels can thereby increase the survival of tidal marsh cordgrass (S. alterniflora) during severe drought by 5–25-fold and shorten the recovery time after die-off from many decades to less than 20 years134 (Fig. 4b). Moreover, ecosystem engineering by ribbed mussels greatly enhances accretion rates where they are present, increasing the resilience of tidal marshes to SLR31.

By contrast, herbivory and bioturbation typically weaken coastal wetland resilience. Herbivores (including many snails, crabs and small mammals), for example, can decrease vegetation biomass and preclude vegetation recovery through consumption, decreasing resilience to droughts136,137,138, although they can increase plant diversity in eutrophic tidal marshes139. Negative effects of herbivores (such as the periwinkle snail Littorina littorea) on coastal wetland resilience can be amplified by pathogenic microorganisms (such as fungi in the genera Phaeosphaeria and Mycosphaerella140) but controlled by predators (such as carnivorous wetland crabs141,142). Bioturbation of sediments by crabs and clams can increase the erosion of tidal flats under increasing waves and rising sea levels143,144, although it could enhance tidal marsh resilience by improving soil oxygen and facilitating plant growth, especially in waterlogged interior marshes145,146.

The roles of local drivers of coastal wetland resilience are conspicuous at dynamic wetland edges, including boundaries between upper and lower zones, transitions from vegetated to mudflat habitats, and the limits of equatorial or poleward ranges, where coastal wetlands experience the strongest cross-ecosystem stressors. For example, by killing vegetation, destabilizing sediments, and widening tidal channels at the lower marsh edges, crabs increase tidal marsh loss to SLR147,148 or extreme storms149. By contrast, mussels can facilitate establishment of tidal marsh grasses at marsh–mudflat boundaries and thereby enhance tidal marsh resilience to SLR and wave disturbances132,150. Finally, competition, facilitation and herbivory can affect the resistance of tidal marshes at their warm range edges to poleward encroachment of mangrove forests under climate warming151,152.

Regional drivers

The resilience of coastal wetlands to anthropogenic threats is also regulated by physical and ecological drivers at regional scales. Ecosystems, including coastal wetlands, do not exist in isolation but form interconnected mosaics with transfer of energy and organisms across boundaries153. For physical drivers, coastal wetlands are typically more resilient to SLR if there are increased levels of sediment supply, which facilitates vertical accretion26, or when their upland topography is flat, so that landward migration of coastal wetlands is attainable154.

Ecological drivers of coastal wetland resilience at regional scales include animals that migrate across ecosystem boundaries, species dispersal through land, water and air, and biotic factors that affect the vertical or latitudinal shifts of coastal wetland boundaries. In the southeastern USA, for example, feral hogs (Sus scrofa) shelter in upland forests during colder months but move into tidal marshes for the warmer months to forage in mussel-rich areas. This foraging can disable cordgrass–mussel mutualism and weaken the resilience of tidal marshes to drought30,155 (Fig. 4c). Conversely, sea otters (Enhydra lutris), blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus), and many fishes that primarily inhabit coastal waters also forage in tidal marshes and consume herbivorous, burrowing crabs that suppress plants and destabilize sediments, thereby enhancing tidal marsh resilience to erosion86,156. Blue crabs also consume herbivorous snails, indirectly facilitating the growth of cordgrass, reducing its die-off during drought, and enhancing its recovery thereafter87.

In places where coastal wetlands have been destroyed and have no or limited seed banks, dispersal of propagules through adjacent land, water and air is essential for wetland recovery. In many tidal marshes, seeds are entrained and transported by the outgoing tides, so tidal connectivity between donor and receiver sites is crucial to recovery157,158,159. Many small mammals and birds facilitate seed dispersal and thereby contribute to plant recovery, particularly in areas where tidal dispersal is limited. For example, small mammals such as hares typically deposit seeds of mid-successional, perennial, high-marsh species from nearby donor sites, whereas birds such as geese deposit seeds of early successional, annual, low-marsh species from distant donor sites160.

Migration of coastal wetlands into adjacent ecosystems under climate change can be affected by ecological factors in adjacent ecosystems. For example, tidal marsh expansion into upland forests driven by SLR can be slowed by competition with upland trees and grasses and by herbivory from ungulates161,162,163. Similarly, with climate warming, mangrove poleward expansion into tidal marshes can be slowed or inhibited by competition from tidal marsh vegetation and herbivory from rodents151,152.

Global drivers

The resilience of coastal wetlands to anthropogenic threats is further regulated by global-scale drivers, including animals that migrate across distant regions. Migratory geese can weaken tidal marsh resilience to SLR by grazing on tidal marshes and increasing marsh-edge erosion. For example, in Westham Island, British Columbia, Canada, tidal marshes accreted by 1–2 cm per year after the experimental exclusion of geese, outpacing the rate of SLR, but the marshes eroded by 1 cm per year in the presence of geese164. In other tidal marshes, however, migratory shorebirds can control the grazing activities of herbivorous animals such as snails directly through consumption or indirectly through transmitting snail-infecting parasites, thereby increasing the resilience of tidal marsh vegetation to drought43,165 (Fig. 4d). In addition to direct and indirect trophic effects, long-range migratory birds can mediate coastal wetland resilience by facilitating seed dispersal166. Many other species such as insects, fishes and marine mammals also migrate across distant regions. Their temporary visits to coastal wetlands can affect wetland resilience through trophic and non-trophic interactions167,168,169, although their effects remain poorly studied overall.

Cross-scale interactions among drivers

The local, regional and global drivers of coastal wetland resilience are not typically independent but can interact concurrently or sequentially. Regional and global drivers can affect coastal wetland resilience by interacting with local drivers. For example, globally migratory shorebirds can interact with local, resident grazing crabs via consumptive and non-consumptive effects (such as fear of predation) to regulate the recovery of tidal marsh vegetation following disturbance43 (Fig. 4a). This role of globally migratory shorebirds, which occurs most often during low tides, can further be complemented by regionally moving fishes that enter coastal wetlands during high tides170,171. Drivers of coastal wetland resilience can be altered by anthropogenic threats at different spatial scales, including those that primarily affect the quality of coastal wetlands, leading to weakened or enhanced resilience to other threats.

Resilience through conservation

The scientific understanding of coastal wetland resilience to anthropogenic threats should be translated into conservation policies, strategies and actions that work to protect and improve both the extent and quality of coastal wetlands. Here, we first review existing conservation efforts, focusing on the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, and then highlight priorities to enhance conservation through the lens of scale.

Existing conservation efforts

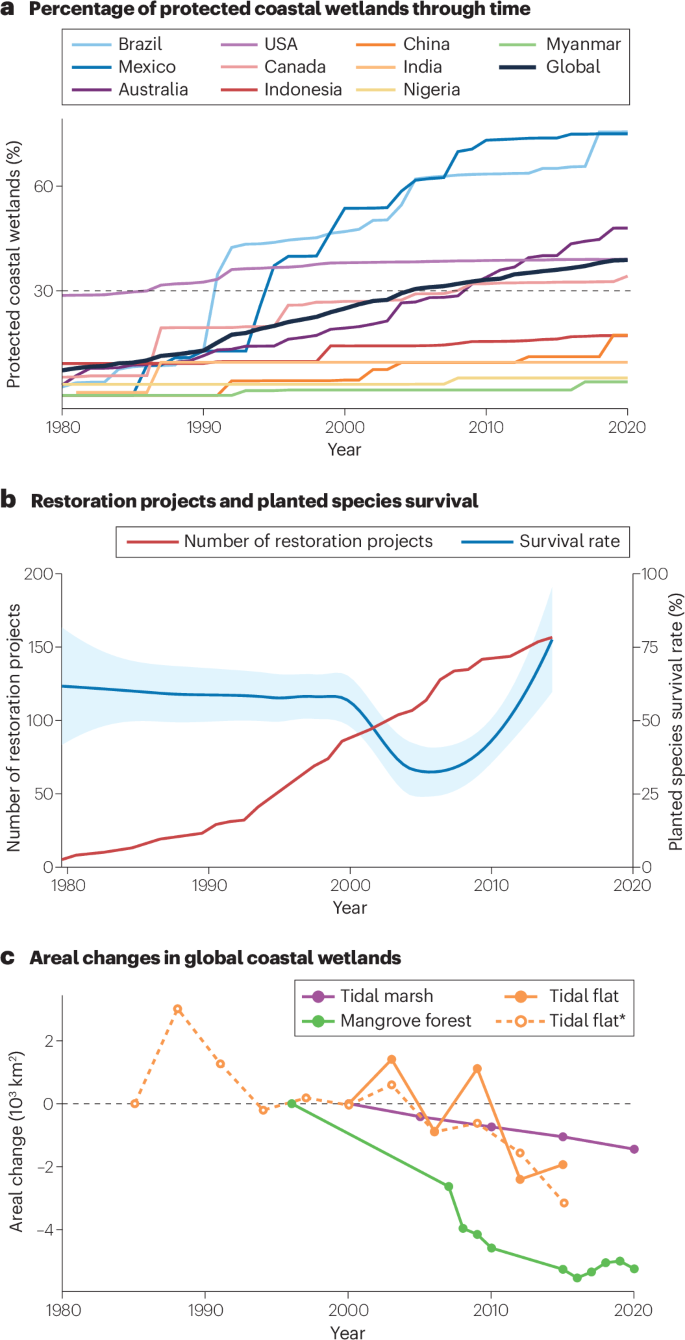

Coastal wetland conservation efforts include establishing laws and regulations to reduce anthropogenic threats, setting up protected areas, restoring the physical conditions of the degraded habitat, and rewilding populations of threatened flora and fauna. These efforts date back to the 1950s and have increased rapidly over the past four decades. In the UK, for example, sections of tidal marshes were designated as protected areas for the preservation of bird habitat following the establishment of the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act172. In China, mangrove restoration has increased considerably since the 1980s173. Globally, less than 10% of coastal wetlands were under some level of protection before the 1980s, a percentage that has gradually increased to 35% in the 2020s (Fig. 5a) with a largely consistent pattern across tidal marshes, mangrove forests and tidal flats (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Although many restoration projects are undocumented, those reported have increased since the 1990s (Fig. 5b).

a, Temporal trends in estimated percentage of coastal wetlands that are protected, globally or in representative countries or regions. The dotted line indicates the 30% protection target of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Protected areas with unreported year of designation were included throughout. b, Temporal trends in the number of coastal wetland (tidal marsh and mangrove forest) restoration projects reported globally alongside the average reported survival rate of planted species (the line represents loess smoothing and the shaded error represents the 95% confidence interval) in restoration projects. c, Relative changes in the global extents of coastal wetlands since the 1980s. Areal changes in the first year analysed (1984 or 1999 for tidal flats, 1996 for mangrove forests, and 2000 for tidal marshes) were set to zero. For tidal flats, the solid line denotes trends from 1999 to 2016 based on 61.3% of the mapped area, and the dotted line (*) denotes trends from 1984 to 2016 based on 17.1% of the mapped area, where sufficient satellite images were available209. Despite increasing protection and restoration efforts, coastal wetlands around the globe continued to decrease. Estimations in panel a were derived from data in refs. 177,208,209 and maps available at Protected Planet, the data in panel b were extracted from ref. 210, only those where the year of data collection was given were included and those where only the year of publication was given were excluded. The data in panel c were extracted from ref. 16 for tidal marshes, ref. 209 for tidal flats and ref. 177 for mangrove forests.

Although the percentage of protected coastal wetlands has already surpassed the global target of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework for 2030, key gaps remain in the protection for coastal wetlands. There are substantial disparities in protection among countries. Some countries or regions including the USA and Australia have protected around 35–75% of their coastal wetlands, whereas many others (including India, China, Myanmar and Indonesia) have so far protected only 5–20% of their coastal wetlands (Fig. 5a). Many of the countries or regions where coastal wetlands are less protected have expansive coastal wetlands but are densely populated and/or have a GDP per capita lower than the global coastal average (Table 1). In many cases protected areas are not fully protected or the protecton is not fully enforced (such as fishing still being allowed). Others are newly established, or are small and/or isolated, which probably undermines their effectiveness and resilience174, although their performance remains often unassessed. Critically, protected areas are typically targeted to restrict local and specific anthropogenic threats, rather than the many other threats operating at regional and global scales. As such, even when local anthropogenic threats are effectively controlled, protected areas can still suffer from regional and global threats such as watershed pollution, tidal restriction, species invasions, droughts, SLR and barriers to landward migration137,175,176 (Fig. 3).

Key gaps also remain in the restoration for coastal wetlands. Despite rapid increases in restoration projects since the 1990s, trends varied among different types of coastal wetland. The number of mangrove forest restoration projects has increased steadily since the 1980s, but very few new tidal marsh restoration projects have been registered after the 2000s (ref. 19) (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The majority of reported restoration projects were small in spatial extent, short-lived or assessed only within the first 1–2 years after implementation18. These issues are often constrained by local and regional policies and funding mechanisms173. Across these many decades of restoration projects, the reported survival rate of planted species in tidal marshes remained around 50%, although the survival rate of planted mangroves first decreased and then increased after the 2000s (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 1b). Recovery in the extent and quality of coastal wetlands (including tidal flats without vegetation, where success should be assessed using metrics such as extent change rather than the survival rate of planted grasses and trees) after restoration is often unassessed. Consequently, whether restoration is on a trajectory to meet the restoration target of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework for 2030, at any level, remains highly uncertain.

Priorities to enhance conservation

Increasing conservation efforts have reversed the loss of coastal wetlands in some regions16,177, but global-scale loss has only declined, rather than being reversed (Fig. 5c). Moreover, it is likely that loss was much greater before the 1980s, when the emergence of satellite imagery enabled monitoring coastal wetlands at global scales to begin178,179,180 (Box 1). To date, conservation efforts remain far from recovering these historic losses. Therefore, increasing the extent of coastal wetlands by reducing anthropogenic threats, such as reclamation and tidal restriction, must continue where feasible. However, for coastal wetlands currently protected or subject to restoration efforts, and in places where further expanding their extent is infeasible owing to natural, social, economic and political constraints, it is essential to maintain and enhance their quality and resilience. The following four priorities are intended to reduce threats to coastal wetlands and enhance their resilience at local, regional and global scales. Incorporating these priorities into conservation practice will, in some places, require transformative change in conservation policies, regulations and laws181,182.

Strengthening local conservation by enhancing the quality of coastal wetlands

Traditionally, conservation efforts have focused on maintaining and increasing the extent of coastal wetlands by reducing local threats. These efforts have included setting up protected areas, restoring the physical habitat by removing farms and tidal gates, and planting grasses and trees in tidal marshes and mangrove forests. Despite success in maintaining and increasing the extent of coastal wetlands, these conservation efforts often fail to enhance the quality of coastal wetlands183. Filling this conservation gap is critical and could be achieved by optimizing the physical conditions of coastal wetlands and incorporating the local drivers of resilience into conservation plans. For example, mimicking key traits of habitat-forming species to locally suppress hydrodynamic stress using biodegradable establishment structures greatly enhanced the restoration success of cordgrass in tidal marshes184. Co-restoration of mutualistic mussels or carnivorous crabs can enhance the establishment and recovery of vegetation at tidal marsh restoration sites142,185. Furthermore, protected areas are often established in remote areas with low value for human usage. These areas might not have the local features that confer resilience to anthropogenic threats such as SLR and extreme climate events. To enhance resilience to anthropogenic threats, future protection efforts could be prioritized for areas with high genetic and functional diversity, and for areas with mutualistic organisms that can enhance the resilience of coastal wetlands.

Improving regional conservation through cross-ecosystem coordination

Conservation efforts to date have generally focused on individual coastal wetlands. However, the connectivity of coastal wetlands with adjacent ecosystems highlights the need to incorporate regional processes in conservation153. Across the landscape and seascape, processes generated in one ecosystem, such as wave attenuation and pollution, can facilitate or plague another, affecting its resilience. It is important to manage such cross-ecosystem interactions for the conservation of both the extent and quality of coastal wetlands. For example, co-protection of an upland buffer zone will be critical to ensure that future wetland migration to uplands is possible and that the extent of wetlands is therefore resilient to SLR. For coastal wetland quality, seascape connectivity can enhance the effects of reserves on fish biomass and species richness in mangrove forests186. Co-restoration of mangrove forests and adjacent oyster reefs has been shown to increase the abundances of both in a Florida estuary187. In practice, the key challenges for successful cross-ecosystem conservation include: increased costs of protection, restoration and monitoring over a much broader spatial extent; large-scale relocation of humans and infrastructure such as farmlands and built-up areas, especially in densely populated areas; and cooperation and coordination across the authorities responsible for the management of different systems such as land and ocean. A growing number of positive examples of regional cooperation, for instance in the form of the Chesapeake Bay Program in the USA and the Natura 2000 protected areas network in Europe, show potential for regionally coordinated conservation.

Promoting global conservation by empowering low-income nations and engaging Indigenous communities

Despite increasing evidence that coastal wetlands are affected by global processes, they have rarely been accounted for in conservation efforts, in part because they are beyond the immediate control of local and regional agencies and stakeholders. However, long-term conservation efforts rely on reducing global threats (including global warming) and managing global drivers of resilience. Recent examples of global-scale initiatives include the Blue Carbon Initiative (focusing on the protection and restoration of coastal wetlands for climate change mitigation and adaptation) and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands (focusing on conservation of wetlands, especially endangered wetland species, and on the wide use of wetland resources). In addition to increasing the extent of protected and restored coastal wetlands by including more and larger sites in more regions, such initiatives might benefit from considering global-scale processes that affect the quality and resilience of coastal wetlands, such as the migratory routes of keystone species.

Global-scale conservation initiatives cannot be feasible without empowering low-income nations, engaging Indigenous communities, and harnessing traditional knowledge. Many coastal wetlands are found in densely populated, low-income nations, which often lack the technical and financial resources required to implement and scale up conservation efforts. As such, international assistance through programmes such as the United Nations’ Green Climate Fund can be critical19. As coastal wetlands are often in regions with Indigenous communities who typically have a long-term interest and deep understanding of their surroundings, coastal wetland conservation can benefit from recognizing their traditional knowledge and involving them in decision-making. These efforts can foster ownership, enhance the enforcement and efficacy of conservation efforts, and ensure blue justice188,189. Traditional knowledge, for example, has been found to be important in selecting appropriate sites, choosing the right mangrove species, and scheduling the planting period, making a vital contribution to the success of mangrove forest restoration in the Baie des Assassins on the southwestern coast of Madagascar190.

Facilitating conservation at all scales through advanced technologies

Coastal wetland conservation at local, regional and global scales can all benefit from advances in technology such as robotized machinery and artificial intelligence (AI). The restoration costs of coastal wetlands per unit area are currently ten-fold higher than in terrestrial systems, in part owing to the logistic challenges of working in highly dynamic, muddy and frequently flooded environments18,191. Cutting costs is urgently needed, such as by the use of robotized machinery. Similarly, current monitoring of anthropogenic threats and conservation performances is often manual, time-intensive and cost-intensive, and is done sporadically. These activities can be improved by harnessing automation and AI. Furthermore, the use of AI could facilitate exploring large and complex data, which could feed into automatic predictive modelling and decision support systems. This capacity could help to identify coastal wetland sites that are most promising for conservation, as well as the anthropogenic threats to target conservation sites and the key drivers of their resilience at various scales. In addition, AI has the potential to drive innovation and optimization of conservation methodologies by analysing dedicated learning experiments192 and tailoring conservation methodologies to specific local or regional conditions, such as tidal amplitude, wave exposure and sediment supply. Despite the potential advantages of integrating advanced technologies into conservation practice, doing so will require training and collaboration among ecologists, AI scientists, engineers from industry and conservation practitioners, which could be particularly challenging to achieve in low-income regions.

Summary and future directions

Over the past decades and centuries, anthropogenic threats to coastal wetlands have expanded from localized disturbances to a combination of stressors operating within and across local, regional and global scales, reducing both the extent and quality of coastal wetlands. The resilience of coastal wetlands to anthropogenic threats is fundamentally driven by their quality, which is affected by physical conditions (such as sediment supply, tidal regime and topography) and ecological conditions (such as trophic interactions that can transcend scales through resident, regionally or globally migratory species). The drivers of coastal wetland resilience across different scales, however, have not been studied in detail nor fully incorporated into conservation efforts. Although conservation efforts to maintain and increase the local extent of coastal wetlands must continue, maintaining and enhancing the quality of coastal wetlands is critical for their functioning and long-term resilience. Below, we outline priorities for future research that should inform conservation efforts.

The first need is to better understand and predict the resilience of coastal wetlands to multiple co-occurring anthropogenic threats. Current understanding of coastal wetland resilience has largely focused on one or two threats, but coastal wetlands face multiple anthropogenic threats at local, regional and global scales (Fig. 3). These threats vary in their duration, magnitude and frequency. Moreover, multiple anthropogenic threats can interact synergistically, additively or antagonistically to complicate predictions about the resilience of coastal wetlands193. Although local threats have been reported in a few cases to affect the resilience of coastal wetlands to climate change13, more studies are needed to understand and predict how interactions among multiple threats at all spatial scales affect the resilience of coastal wetlands. Studies that quantify co-tolerances of coastal wetlands to multiple threats across spatial scales194,195, that experimentally test a randomly selected gradient of increasing threat number (analogous to biodiversity effects on ecosystem functions196), and that develop mechanistic experiments and models that incorporate the interactions of multiple threats197,198 will be particularly useful.

The second need is to investigate whether and how ecological and physical factors interact to modify coastal wetland resilience. Studies of the drivers of coastal wetland resilience have traditionally focused on vertical or lateral changes associated with sedimentation, tidal regimes and topography. The role of vegetation and bioturbation in modifying sedimentation processes has been recognized as a critical biophysical process that mediates coastal wetland resilience32,144,199. A growing number of studies, often on tidal marshes and in a few regions such as North America, are showing that diversity, evolution and species interactions can affect the resilience of vegetation or other target species. However, it remains largely unknown how these ecological processes might propagate to affect wetland vertical or lateral changes associated with sedimentation processes, ultimately affecting changes in their spatial extent. It is necessary to develop a coupled physical–ecological understanding of coastal wetland dynamics in order to screen for the critical, physical or ecological drivers of resilience and to identify direct or indirect pathways to operationally enhance resilience, thereby informing the development of more effective and innovative conservation strategies31. To do so, future research on mangrove forests, tidal flats and tidal swamps from understudied continents such as Africa, Asia and South America should be especially encouraged.

A final need is to develop conservation approaches that enhance the quality, and thus the long-term resilience, of coastal wetlands. Although the field’s understanding of coastal wetland resilience and its drivers is rapidly expanding, novel research has not yet been translated into practical conservation approaches. Findings from undegraded natural areas might not be applicable to restoration of degraded areas. For example, herbivores typically help to increase plant diversity in relatively natural areas but decrease it in areas under restoration200. Thus, the effectiveness, costs and feasibility of conservation approaches aimed to enhance the quality and resilience of coastal wetlands should be tested in realistic conservation scenarios prior to application and with input from local communities who stand to benefit from these conservation efforts. These conservation approaches could include co-restoring plants and mutualistic species, rewilding migratory top predators and co-protection of adjacent uplands and seas. The development of such conservation approaches can be facilitated by creating scalable mechanistic models of coastal wetland dynamics that integrate different drivers of coastal wetland resilience and potentially by applying AI tools.

In the coming decades, the world’s coastal zones will probably experience stronger human–nature interactions as populations grow and humanity accelerates the exploration and utilization of coastal marine resources201, while facing increasing threats from SLR and storms in a warming climate202,203. An improved scientific understanding of coastal wetland resilience to anthropogenic threats across local, regional and global scales is necessary to inform what conservation actions will be key for the long-term persistence of coastal wetlands. The future of coastal wetlands and, ultimately, the harmonious coexistence of humanity and nature in coastal zones, will depend not only on improved science, but also on society’s prompt actions to enhance the extent and quality of coastal wetlands through science-based conservation at all scales.

Responses