Codes for entanglement-assisted classical communication

Introduction

Entanglement serves as a valuable resource in many quantum communication and quantum information processing tasks. Pre-existing entanglement can sometimes enhance the information transmission capabilities of quantum channels. One of the earliest results demonstrating this power of entanglement-assisted communication came in 1992. Wiesner introduced the technique of super-dense coding1 in which a sender can communicate two classical bits while sending a single qubit across a noiseless quantum channel, provided they have pre-shared entanglement. Subsequently, Bennett et al.2 showed that the classical capacity of some noisy quantum channels can be significantly increased with the assistance of unbounded pre-shared entanglement between the sender and the receiver. In 2002, Bowen3 presented a class of entanglement-assisted (EA) quantum codes that achieve the quantum EA channel capacity when a certain amount of shared entanglement per channel use is provided. A few years later, Brun et al.4 proved that assisting a quantum channel with entanglement allows quantum codes to have better parameters than codes not aided by entanglement.

So far, entanglement-assisted communication has been largely explored through an information-theoretic lens. This means, prominently questions on entanglement-aided capacities have been addressed2,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. For instance, Hsieh and Wilde12 proved a capacity theorem establishing the maximum rate at which one can transmit classical and quantum information simultaneously across a noisy quantum channel supported by entanglement. Shadman and Bruß10, on the other hand, consider a similar problem setting but focus on transmitting only classical information. They determine the super-dense coding capacity for specific resource states in the presence of noise. The interest in capacity questions is completely natural considering how the concept of capacity forms a central theme in information theory. Its significance can be seen in Shannon’s noisy-channel coding theorem13, a foundational result lying at the heart of information theory. Shannon showed that for a noisy channel, given an information transmission rate below capacity, the transmission error probability asymptotically tends to zero when the coding length increases.

The problem of reliable transmission of either classical or quantum information, or a combination of both, across n uses of a quantum channel with the help of entanglement has been explored from a coding theory perspective as well, although this approach has been much less prevalent. This perspective involves addressing the problem in a practical setting, defined by specific parameters like a fixed code length and a set of errors that can be perfectly corrected. Kremsky et al.14 proposed a generalization of the stabilizer framework to capture entanglement-assisted hybrid codes. Here “hybrid” refers to the fact that these codes can transmit both classical and quantum information at the same time. The authors give examples of hybrid codes, but none that transmit only classical information. Their work primarily focuses on establishing a framework and conditions for error correction without addressing how to find codes that meet these conditions. Also, they do not connect the parameters of the code described in their “extended stabilizer formalism” with the properties of the corresponding classical codes. In particular, there are no constructions in the literature for codes designed for entanglement-assisted classical communication.

While considerable attention has been devoted to exploring EA quantum codes, the exploration of EA classical codes has been notably scarce. A common assumption is that an unlimited amount of entanglement can be used, but the question of less entanglement has, for example, been considered in ref. 3. Directly using EA quantum codes to transmit classical information is inferior to the solution we present here. This is related to the fact that the parameters [[n, k, d; c]]q of an EA quantum code obey the classical Singleton bound d ≤ n−k + 1 given in Eq. (3) below15, while our codes can exceed that bound.

Addressing these aspects, in this paper, we present an explicit encoding scheme that can transmit classical information using a qudit channel n times assisted by c ≤ n maximally entangled qudit pairs when, at most, d−1 erasures occur. We demand perfect error correction, i.e., the probability of error after decoding should be zero. Our scheme is “explicit” in the sense that we provide a construction method that works for all parameters within a certain range and allows us to easily deduce the parameters of the resulting code.

The flow of the paper is as follows. First, the task of transmitting classical information over a quantum channel using maximally entangled pairs is simplified by reducing it to a classical one. We then present an explicit encoding scheme, offering practical methods for creating directly implementable codes. Following this, we derive Singleton-like bounds, compare our scheme to these bounds, and identify parameter ranges where the scheme is optimal. We then analyze how our proposed EACC scheme surpasses classical protocols in terms of error correction capability and information transfer rate. Finally, we conclude by discussing potential future directions and implications of our work.

Results

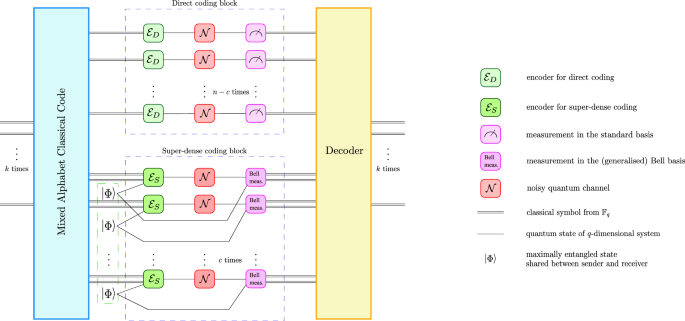

Reduction to a classical problem

Let q be the dimension of the quantum system associated with the quantum channel. We distinguish two cases. If we do not have entanglement available, for each use of the quantum channel we can send q mutually orthogonal states over the channel (one at a time), and the receiver measures in the corresponding basis. In case we have entanglement available, we can send q2 different messages per use of the channel with the super-dense coding protocol16 which requires one maximally entangled pair for each single transmission. This allows for our problem to be translated to a classical one. The amalgamation of direct coding and super-dense coding results in a combination of classical channels: n−c classical channels transmitting one symbol each and c classical channels transmitting two symbols each. Each of the c symbols being communicated via the super dense-coding protocol can be interpreted as two symbols from an alphabet containing q letters. The problem now reduces to finding an encoding of messages into a string of n symbols, where n−c of them come from an alphabet ({{mathcal{A}}}_{q}) with q letters and c symbols are from the alphabet ({{mathcal{A}}}_{{q}^{2}}={{mathcal{A}}}_{q}times {{mathcal{A}}}_{q}) with q2 letters. An erasure during a single transmission in the context of a super-dense coding scheme implies that two classical symbols are erased, otherwise a single symbol is considered to be erased. The setting is illustrated in Fig. 1. In the extremal case of c = 0 we can use a classical error-correcting code over the alphabet ({{mathcal{A}}}_{q}). When n = c we can use a code over ({{mathcal{A}}}_{{q}^{2}}). The case of n = c has been considered earlier in ref. 17, Proposition 11. We denote the code by ({mathcal{C}}={[n,k,d;c]}_{q}), where n is the number of channel uses, and c is the amount of entanglement required by the code. The parameter d is the minimum distance of the code. A code with minimum distance d can correct a maximum of d−1 erasures or ⌊(d−1)/2⌋ errors. An erasure is an error at a known position18. Further, k is the dimension of the code, that is, qk different classical messages can be sent across the channel. From here on, we assume q to be a power of prime. Lastly, the alphabets ({{mathcal{A}}}_{q}={{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) and ({{mathcal{A}}}_{{q}^{2}}={{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}) are chosen to be finite fields with q elements and q2 elements, respectively. For an introduction to finite fields and the basics of coding theory see, for example, ref. 19 or ref. 20.

The mixed alphabet classical code maps k input symbols to n outputs from different alphabets. Then, n−c of the symbols are transmitted using direct coding and c symbols are transmitted using super-dense coding. The encoder ({{mathcal{E}}}_{{rm {D}}}) maps one classical symbol from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) onto a qudit which is transmitted across a noisy quantum channel ({mathcal{N}}) and measured in the corresponding basis. This process is repeated n−c times as illustrated by the direct coding block. The encoder ({{mathcal{E}}}_{{rm {S}}}) encodes a pair of classical symbols (identifying ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}) and ({({{mathbb{F}}}_{q})}^{2})) onto one half of a maximally entangled state (leftvert Phi rightrangle). This encoded state is then transmitted across a noisy quantum channel ({mathcal{N}}). The other half of the maximally entangled state (leftvert Phi rightrangle) is shared with the receiver noiselessly. Upon reception, the receiver performs a measurement in the Bell basis on the received pair of states. This process is repeated c times as illustrated by the super-dense coding block. Finally, the decoder corrects errors and outputs a classical message.

Code construction

We use the following modified version of the concept of Reed–Solomon codes21 to construct the code. Let ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}[x]) denote the set of polynomials in x with coefficients in ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) and let ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}^{n-c}times {{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}^{c}) be the direct product of vector spaces. We obtain our mixed alphabet Reed–Solomon code ({[n,k,d;c]}_{q}subseteq {{mathbb{F}}}_{q}^{n-c}times {{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}^{c}) by evaluating all polynomials (fin {{mathbb{F}}}_{q}[x]) of degree at most k−1. More precisely,

where n−c = n1 distinct evaluation points from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) and c = n2 distinct points from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}setminus {{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) are denoted by αi and γj, respectively. The elements of ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}setminus {{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) come in conjugate pairs {γ, γq}. We choose only a single element γ from each conjugate pair to be present among our evaluation points. This gives rise to the partitioning of the n evaluation points as n = n1 + n2, where n1 is the number of elements from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}), and n2 is the number of elements from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}).

In the standard classical setting, without entanglement assistance, one cannot achieve a rate R = k/n higher than one, since the size of the code qk cannot exceed the number qn of different strings over an alphabet with q symbols. In contrast, our scheme allows k to be larger than n (whenever c is non-zero) while maintaining an injective encoding. To see this, consider the situation at the receiver’s end. In order to retrieve the encoded information from a received codeword, the receiver uses the fact that a polynomial of degree at most k−1 is uniquely determined by its value at k evaluation points. For evaluation points (gamma in {{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}setminus {{mathbb{F}}}_{q}), we have f(γq) = f(γ)q. Hence if the receiver knows the component of a codeword corresponding to an evaluation point γj, he can also compute the evaluation at the conjugate point ({gamma }_{j}^{q}). This means that in the error-free case the receiver actually has n1 + 2n2 = n + n2 evaluation points at his disposal to identify the polynomial, i.e., interpolation is possible as long as the degree of the polynomial is strictly smaller than the number of evaluation points. Therefore we have deg(f) < n1 + 2n2, or equivalently, k−1 < n1 + 2n2 = n + n2.

The length of our code is limited by the maximum number of elements one can pick from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) and the maximum number of single elements one can pick from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}). Therefore we have 1 ≤ n ≤ q +(q2−q)/2 = (q2 + q)/2. We note that we can extend the length by one and increase the minimum distance by one as well, using “the point at infinity”. For simplicity, we do not consider that option in what follows.

For a linear code, the minimum distance d of the code equals the minimum weight (number of non-zero components) of a non-zero codeword. It can be deduced from the maximum number of evaluation points that are roots of a polynomial (fin {{mathbb{F}}}_{q}[x]) of degree at most k−1.

For n1 ≥ k−1 we have

since there exists a polynomial f of degree at most k−1 with coefficients in ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) that has the maximal possible number of k−1 roots among the n evaluation points. The distance in Eq. (2) meets the so-called (classical) Singleton bound

with equality. The bound is derived as follows. A code with distance d can correct d−1 erasures. Erasing d−1 of the n symbols results in strings of length n−d + 1. Since all these strings have to be different, we get the bound k ≤ n−d + 1, which is equivalent to Eq. (3).

For n1 < k−1, we have

This is because of the following reasoning. We know that a polynomial of degree at most k−1 has at most k−1 roots. In the worst-case scenario, all of the n1 evaluation points from the base field ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) are roots, and the remaining k−1−n1 roots come from the extension field ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}). If an element γ in ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}) is a root, its conjugate partner γq is also a root. Since we have only single elements present among our evaluation points, not their conjugate partners, this implies that, in the worst case, at most half of the remaining k−1−n1 roots are among the n2 elements. The inequality follows from the fact that n1 < k−1 implies that n2 = n−n1 > n−k + 1. Hence, the minimum distance in Eq. (4) exceeds the classical Singleton bound in Eq. (3).

In the case of n1 < k−1 we have the freedom to choose n1, n2 according to n = n1 + n2 and the constraints listed below such that the minimum distance (4) of a code ({mathcal{C}}={[n,k,d;c]}_{q}) is maximized. This optimization involves picking as many evaluation points c = n2 from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}backslash {{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) as possible, constrained by c = n2 ≤(q2−q)/2. The number of evaluation points one can pick from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) is restricted by the values of n, c and q, giving us n−c ≤ n1 ≤ q. Also, we have 0 ≤ c ≤ n.

Bounds

We now examine different ranges of n, c and k to determine when our code is optimal with respect to certain bounds.

The size of our code, i.e., the number of classical messages that our code can transmit, can be bounded, assuming that the code can correct a maximum of d−1 erasures.

Each of the n1 symbols in a codeword can be visualized as a block of length one. Each of the n2 symbols in a codeword can be seen as a block of length two. Overall, a codeword of length n contains n1 blocks from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) and n2 blocks from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}). The blocks from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}) contain two symbols from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}) per block, allowing us to identify each element of ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}) with an element in ({({{mathbb{F}}}_{q})}^{2}). This means erasing an element from the extension field corresponds to erasing a block of two symbols. First, assume that n2 ≥ d − 1. Then, in the worst case, all the d−1 erasures occur within the n2 blocks from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}). After the erasures have occurred, we are left with strings of n2−(d−1) symbols from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}) and n1 symbols from ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}). All these strings have to be different. This results in the bound

This is the block error bound. Essentially, in the analysis above we have customized the bound in ref. 22 to our situation. The block error bound (5) is met when (nle q+frac{{q}^{2}-q}{2}), n−q ≤ c. In this case, the minimum distance is d = ⌈(n−k + 1 + c)/2⌉ as given in Eq. (4). In the scenario when n2 < d−1, the block error bound reduces to the Singleton bound k ≤ n−d + 1. This bound is met as long as n1 ≥ k−1 (see Eq. (2)).

We continue examining general bounds on the parameters of our setting. In this context, ref. 23 establishes a bound on hybrid codes that can transmit classical and quantum information simultaneously with the assistance of entanglement. We apply the bound in ref. 23 to our scenario. Since we are not transmitting quantum information, their parameter Q = 0 in our case. From Theorem 8 in ref. 23 and the corresponding equations (54)–(56) therein, we obtain the inequalities:

Here t is a parameter such that t ∈ [0, 1]. Note that in ref. 23, all logarithms use base 2, while our parameters k and c are related to base q. Hence the range ([0,{log }_{2}q]) for the parameter t in ref. 23 yields the range [0, 1] in our setting. Also, the amount of classical information k we are sending is C in their case, and the amount of available entanglement c for us is E in their scenario.

Consider the inequalities (6) and (8). Fixing all but k and t, we see that the maximum value of k is achieved when the corresponding bounds on k are equal. We compute the intersection point as (n−d + 1)(1 + t) = c+(n−d + 1)−t(d−1) giving us t = c/n. Particularly, we find that t = c/n lies in the interval [0, 1]. When we substitute t = c/n in Eq. (7) we find that it is fulfilled. This means ({k}_{max }=(n-d+1)(1+c/n)).

Using the above analysis, we obtain the following quantum-bound:

Equivalently, this gives the following bound on the distance

The main question that we seek to answer in this section is for which range of n, k and c the code we have constructed is optimal. To reach the maximal integral value of k in Eq. (9), we get the condition

In this case, we say that our code achieves dimension optimality.

To reach the maximal integral value of d in Eq. (10), we get the condition

In this scenario, we say that the code achieves distance optimality. Distance and dimension optimality are related as follows. When Δ < n/(n + c), we have dimension optimality. When n/(n + c)≤ Δ < 1, we have distance optimality but not dimension optimality since fixing all other parameters of the code we could increase the dimension by one without violating the bound (10). This means that dimension optimality is harder to achieve and implies distance optimality as well.

For the minimum distance in Eq. (4) we have (Delta =n+1-frac{kn}{n+c}-lceil (n-k+1+c)/2rceil). As a reminder, the minimum distance given in Eq. (4) is obtained after imposing the conditions n ≤ q +(q2−q)/2 and n−q ≤ c. We know that when n = c, we can use super-dense coding and obtain optimal solutions. Therefore we only consider the case n > c. The ranges of k for which our code is distance optimal are as follows

When n−k + 1 + c is even, we reach dimension optimality only for k = n + c which implies d = 1. However, when n−k + 1 + c is odd, we reach dimension optimality when (k > n+c-frac{2n}{n-c}).

Note that for linear codes, the dimension k is an integer, while the upper bound (9) on the dimension is, in general, non-integral. This means that when the bound is non-integral, it might be possible to find larger codes, but they cannot be linear. However, as we have shown, in specific instances where the upper bound is integral, linear codes attain the bound (9).

Discussion

Our proposed protocol achieves quantum advantage by surpassing the capabilities of classical codes through the use of entanglement. In our approach, entanglement strengthens error correction by increasing the minimum distance of the codes. We can see this using

from Eq. (4) where the parameter n2 equals the required amount of entanglement c ≥ n−k + 1. If we fix k, with more entanglement, we can achieve a higher minimum distance. At the same time, fixing the distance d, with more entanglement, we get a higher dimension k and, in turn, a higher rate. Therefore, in our scenario entanglement helps us both to increase the distance or to increase the rate.

Moreover, entanglement allows us to achieve significantly higher minimum distances than what is possible classically without entanglement. Consider the following example. A code [34, 20, 22; 28]8 using c = n2 = 28 maximally entangled pairs achieves a minimum distance of 22. In contrast, without the use of entanglement, a linear code with parameters [34, 20, d]8 can attain a maximum minimum distance of only 12. Furthermore, only a code [38, 20, 10]8 is explicitly known24. To illustrate further, consider fixing the distance instead of the dimension. That is, we might ask what the largest possible code with distance 22 could be. Without the use of entanglement, a linear code with parameters [34, k, 22]8 can achieve a maximum dimension of only 1024. In contrast, with entanglement assistance, we achieve twice the dimension, specifically k = 20.

In general, entanglement helps to achieve better code parameters in our scheme. Consider the code rate R = k/n. As discussed earlier in this section, there exists a trade-off between maximizing the rate for efficient information transmission and increasing the minimum distance for reliable error correction. Finding the best trade-off is an important question in coding theory.

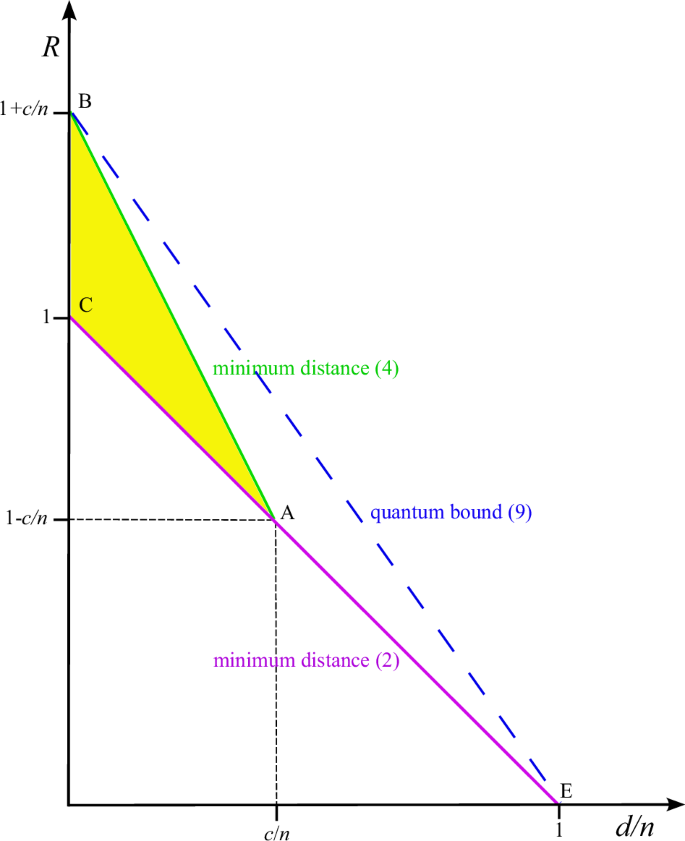

In Fig. 2 we illustrate this trade-off for the code we constructed. We plot the code rate R as a function of the normalized minimum distance d/n in the asymptotic limit, ignoring additive terms that vanish when n goes to infinity. When n1 ≥ k−1 our code with minimum distance (2) achieves rates represented by the line AE. Conversely, when n1 < k−1, our code with minimum distance (4) achieves rates represented by the line BA. Note that the line segments BA and AE agree with the block error bound. The region ABC encompasses points where the rate is greater than one and also includes points with rates less than one, all of which still exceed the Singleton bound, indicating that we are surpassing the performance of any classical code. Entanglement is the reason we can reach these higher rates unattainable by classical means within this range. The line AE indicates the range when our codes meet the Singleton bound. While the length of a classical MDS code with 1 < k < n−1 cannot exceed 2q−2 (see ref. 25, p. 94), our entanglement-assisted codes can have lengths up to (q2 + q)/2.

The code rate R = k/n of our mixed-alphabet Reed–Solomon code is plotted as a function of the normalized minimum distance d/n in the asymptotic limit.

We now examine certain additional aspects of our protocol. Our scheme allows to use the mixed alphabet Reed–Solomon codes introduced here. Using not only evaluation points from the field ({{mathbb{F}}}_{q}), but also from the field ({{mathbb{F}}}_{{q}^{2}}) we obtain longer codes, extending the length of optimal codes for fixed parameter q from O(q) to O(q2). The scheme is not restricted to these codes. One can use other mixed alphabet codes or error-block correcting codes26.

Also, our scheme is not restricted to the setting of perfect entanglement. Noisy entanglement (studied widely in the literature) results in errors in the super-dense coding protocol, which can equivalently be treated as errors during the transmission. In the error correction process, as long as the number of errors plus the number of “bad” entangled states is less than half of the minimum distance, our scheme will still work.

While our scheme provides an advantage over unassisted classical codes, we reach the quantum bound (9) only for specific parameters. We leave it to future research to determine whether there are entanglement-assisted codes for classical communication whose parameters lie in the region BAE of Fig. 2.

Finally, we would like to point out that our scheme does not require quantum memory or quantum computation. It only uses the primitive of super-dense coding that has been experimentally demonstrated27,28.

We have thus designed an explicit protocol together with its parameters for EA classical communication. Our research provides an avenue to illustrate how entanglement can boost various finite-length communication protocols. In certain scenarios, using entanglement can enable a code to correct twice as many errors compared to a code with similar parameters without entanglement assistance. Additionally, in specific cases, entanglement allows a code to achieve a rate higher than one, a feat that is not possible classically without entanglement.

One of the open problems is to find coding schemes whose parameters are in the region BAE of Fig. 2. As the classical codes underlying our scheme meet the block error bound, codes reaching the quantum bound BE are unlikely to be derived from our reduction to a classical problem.

Our work paves the way for finding new explicit code constructions as well. Also, hybrid protocols for simultaneously sending both classical and quantum information with the assistance of entanglement can potentially be obtained by combining our scheme with existing schemes for EA quantum communication. Developing such hybrid codes, facilitated by our code construction, has far-reaching benefits. Explicit hybrid protocols have the potential to enhance error correction and secure communication and may play an important role in quantum computing tasks.

Responses