Coinfection with chikungunya and Zika results in mild disease and distinct inflammatory response

Introduction

Re-emerging arboviruses including chikungunya, Zika, Rift Valley Fever, West Nile viruses, pose significant global health concerns due to their potential for sudden outbreaks and rapid spread, driven by factors such as global travel, urbanization, and climate change1. Chikungunya and Zika viruses (CHIKV and ZIKV) are transmitted by the same mosquito vectors, primarily from the Aedes genus2. Initially reported in Africa, CHIKV has since spread to over 120 countries, and ZIKV to over 80, largely in tropical and subtropical regions3. This expansion has been facilitated by viral adaptability to mosquito species such as Aedes albopictus, which can thrive in a wide range of climates.

Both CHIKV and ZIKV can lead to mild manifestations, such as fever, exanthema, and myalgia. However, severe manifestations can occur, including chronic debilitating arthralgia in CHIKV-infected individuals, congenital abnormalities in ZIKV-infected newborns, and neurological disorders for both viruses4,5,6. The interplay between the host immune response, viral infection, and tropism is a crucial factor in the differences observed among clinical manifestations. CHIKV and ZIKV infections in humans trigger robust innate and adaptive immune responses, including the activation of type I interferons, T cells, and the production of neutralizing antibodies7. However, there are differences in cytokine profiles and cellular responses that reflect their distinct pathogenesis and tissue targeting8. Indeed, CHIKV and ZIKV have structural differences that lead to varied interactions with host cells and, consequently, different assemblies of the immune response9.

Previous research has shown that arbovirus cocirculation, particularly dengue virus (DENV), CHIKV, and ZIKV, is common in highly endemic regions10,11. Previous reports on arbovirus coinfection suggest that the disease commonly presents with mild clinical symptoms12, although severe manifestations, including Guillain-Barré syndrome, encephalitis, and meningoencephalitis, have been observed in rare cases. Severe manifestations have been associated with the presence of CHIKV and ZIKV in cerebrospinal fluid or brain tissue in fatal cases13,14, raising concerns that coinfection could exacerbate neurological outcomes, and to the hypothesis that coinfection could be a risk factor for severe and fatal outcomes in immunosuppressed adults15. Despite the detection of CHIKV and ZIKV in the cerebrospinal fluid, there is no clear evidence that coinfection enhances neuroinvasion, causing brain damage and neurological disorders. To address this gap, the current study evaluates the clinical characteristics of monoinfected and coinfected patients and is the first to assess immunological markers in patients with CHIKV and ZIKV.

Results

Patients with CHIKV and ZIKV coinfection exhibit no distinct clinical characteristics

Coinfection of ZIKV and CHIKV is a significant issue in Brazil, with a prevalence of 1.0%3. During study recruitment, out of more than 300 patients evaluated at the university hospital clinic for symptoms of arboviral disease, 12 patients were identified with concurrent CHIKV and ZIKV infections. This coinfected group had a median age of 39 years, and 75% were women, as shown in Table 1. These coinfected patients were compared to patients with only chikungunya (CHIKV-monoinfected group) or Zika (ZIKV-monoinfected group) infections. The monoinfected patients were selected from those seen at the same hospital and were matched for sex and age, with median ages of 34 for CHIKV and 43 years for ZIKV. Coinfected patients showed a median of 4 days of symptoms at recruitment, compared to medians of 2 days for CHIKV-monoinfected and 3 days for ZIKV-monoinfected patients.

The quantification of viral load by qPCR performed for molecular diagnostics showed that patients infected with CHIKV had lower Ct values, indicating higher viral load when compared to those infected with ZIKV, regardless of their infection status, indicating that ZIKV produces lower viral load than CHIKV (p < 0.0001, Kruskal-Wallis test). Moreover, CHIKV monoinfected patients produced significantly higher viral loads (lower Ct median) than those coinfected (p = 0.015, Mann-Whitney test).

Coinfected patients showed no differences in symptom presentation compared to those in the CHIKV- and ZIKV-monoinfected groups. Patients infected with ZIKV alone experienced a lower incidence of fever during the acute phase. Additionally, there were no differences in the presence of comorbidities or in the medications used during the disease among the groups. None of the coinfected patients reported persistent symptoms after the acute phase, similar to the monoinfected patients

Coinfected patients exhibit a distinct inflammatory profile compared to monoinfected patients

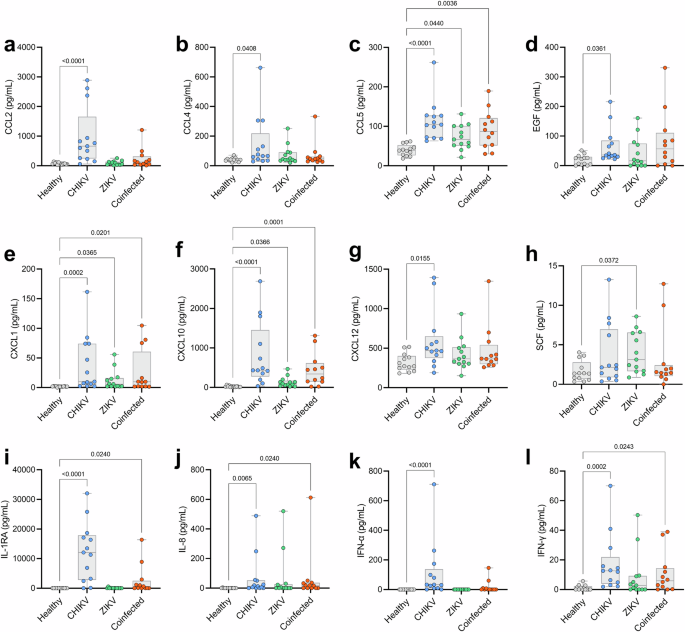

We analyzed 45 cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors in the sera of patients and 13 matched noninfected controls. The analysis revealed that 12 of the 45 (26.7%) immunological mediators were differentially expressed in at least one patient group – CHIKV monoinfected, ZIKV monoinfected, or Coinfected – compared to noninfected controls. Specifically, these mediators include CCL2 (Fig. 1a), CCL4 (Fig. 1b), CCL5 (Fig. 1c), EGF (Fig. 1d), CXCL1 (Fig. 1e), CXCL10 (Fig. 1f), CXCL12 (Fig. 1g), SCF (Fig. 1h), IL-1RA (Fig. 1i), IL-8 (Fig. 1j), IFN-α (Fig. 1k), and IFN-γ (Fig. 1l).

Of the 45 immune mediators quantified in patients’ sera, 12 were differentially expressed and are presented as follows: CCL2 (a), CCL4 (b), CCL5 (c), EGF (d), CXCL1 (e), CXCL10 (f), CXCL12 (g), SCF (h), IL-1RA (i), IL-8 (j), IFN-α (k), and IFN-γ (l). Each dot represents one participant; the boxes indicate the median and interquartile ranges (25%–75%), and the lines denote the minimum and maximum values. Comparisons were made using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test. The p-value is presented for each specific comparison.

Among these mediators, CCL2, CCL4, EGF, CXCL12, and IFN-α showed significantly elevated levels exclusively in CHIKV mono-infected patients compared to non-infected controls. Three mediators, IL-1RA, IL-8, and IFN-γ, exhibited significantly higher expression levels in both CHIKV-infected groups (monoinfected and coinfected), while three chemokines, CCL5, CXCL1, and CXCL10, demonstrated significantly elevated levels across all three infected groups (CHIKV monoinfected, ZIKV monoinfected, and coinfected). One growth factor, SCF, showed significantly elevated levels only in the ZIKV monoinfected group. No correlations were found between Ct values and immune mediators.

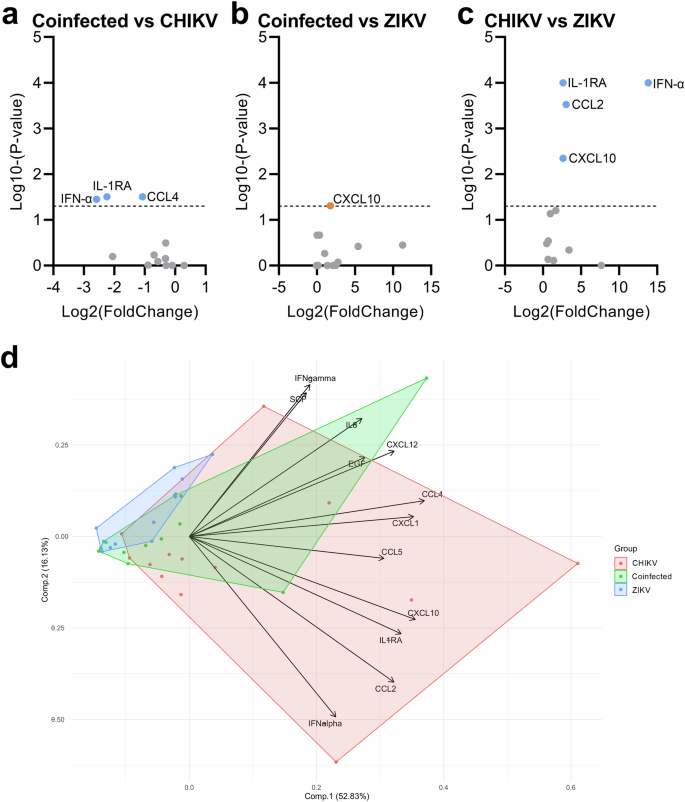

To further explore these 12 differentially expressed mediators, we performed two analyses. First, the comparative analyses indicated that the CHIKV monoinfected group had significantly higher levels of IL-1RA, IFN-α, and CCL4 compared to the coinfected group (Fig. 2a), while the coinfected group displayed significantly higher expression of CXCL10 compared to the ZIKV monoinfected group (Fig. 2b). The CHIKV monoinfected group also showed higher levels of CCL2, CXCL10, and IFN-α than the ZIKV monoinfected group (Fig. Fig. 2c). Additionally, the principal component analysis revealed overlapping groups with no clear segregation (Fig. 2d), displaying greater dispersion in the direction of immune mediators for the CHIKV monoinfected group. In contrast, the coinfected and ZIKV monoinfected groups showed moderate to low dispersion, respectively. Additional correlation analyses between Ct values and cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors did not reveal any significant positive or negative correlations. Similarly, no significant correlations between age and immune mediators were observed.

Comparisons were initially made between levels of immune mediators in pairs of groups, revealing differences between Coinfected versus CHIKV-monoinfected (a), Coinfected versus ZIKV mono-infected (b), and CHIKV versus ZIKV monoinfected groups (c). The volcano plots display differences based on the fold change of quantified cytokines and p-values from multiple comparisons tests (shown as Log2 and Log10, respectively). d Principal component analysis of the 12 differentially expressed cytokines across the three infected groups. The PCA biplot, based on the two principal components (accounting for approximately 70% of the variance), illustrates the overlap of the three patient clusters and the relationships among cytokines, as indicated by the loadings on the graph.

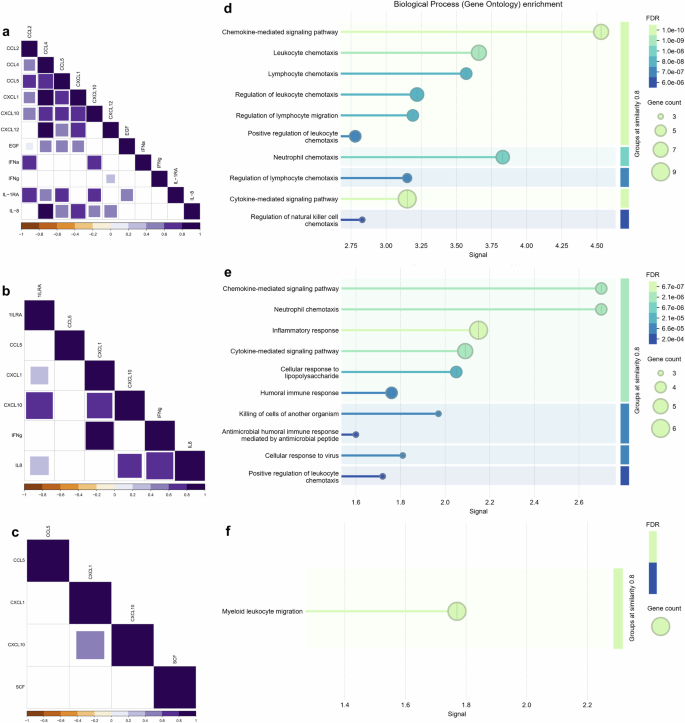

In a complementary manner, correlation analysis was performed for all differentially expressed cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors for each group. The results show that in the CHIKV monoinfected group, among all 12 altered mediators, the chemokines exhibit strong correlations for themselves, with clustering observed for CCL4, CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL10, and IL-8 (Fig. 3a). Conversely, the coinfected group exhibits similar results to that of the CHIKV monoinfected group, but to a lesser extent, mainly involving the mediators CXCL10, IL-1RA, and IL-8 (Fig. 3b). Among the four immune mediators in the ZIKV monoinfected group, there is only a significant moderate correlation between the chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL10 (Fig. 3c). The enrichment analysis of biological processes using STRING protein-protein association networks shows that the immune mediators in the CHIKV monoinfected group are mainly related to chemokine-mediated signaling pathways and neutrophil, leukocyte, and lymphocyte chemotaxis (Fig. 3d). Moreover, the interactions of immune mediators in coinfected patients also show, besides more modest, enrichment of chemokine-mediated signaling pathways and neutrophil chemotaxis, as well as inflammatory and cytokine signaling pathways (Fig. 3e). Finally, the enrichment analysis of the ZIKV monoinfected group shows the presence of the myeloid leukocyte migration pathway (Fig. 3f).

The correlations among differentially expressed cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors in the CHIKV (a), Coinfected (b), and ZIKV (c) groups exhibit distinct patterns, including only positive and significant correlations (with purple intensity indicating the strength of positive values). Non-significant correlations are not shown. Data were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation. An enrichment analysis of protein-protein interaction networks was performed using STRING. Biological processes are depicted for each group: CHIKV (d), Coinfected (e), and ZIKV (f). The false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, and graded p-values are displayed using a green-blue gradient. The signal measure represents the weighted harmonic mean between the observed/expected ratio and -log(FDR). The number of proteins included in the analysis is indicated by circle size.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated a case series of patients coinfected with CHIKV and ZIKV, comparing them to well-matched groups of patients’ monoinfected with each virus and noninfected subjects. In summary, no distinct clinical characteristics were observed in coinfected patients compared to those with only CHIKV or ZIKV infections. Viral load analysis revealed lower ZIKV loads in coinfected patients, regardless of mono or coinfection. Additionally, immune profiling identified an inflammatory signature in coinfected individuals that was intermediate compared to monoinfections, differing from monoinfected patients in specific cytokine expressions.

Our results show that CHIKV and ZIKV coinfected patients exhibited no significant differences in clinical manifestations compared to those with monoinfections, except for a lower frequency of fever in ZIKV-monoinfected patients, a well-documented characteristic of ZIKV infection16. This may be related to the lower viral loads found for ZIKV in both monoinfected and coinfected patients, leading to a less intense immune response in the infected host. Moreover, none of the patients in any group developed severe or persistent symptoms after the acute phase. ZIKV infection is well-known for not producing chronic disease, but previous reports suggest it could be associated with long-term neurological manifestations17. On the other hand, CHIKV infection has a prevalence of chronic symptoms in 40% of patients18, which was not observed in the present study. Based on our results, we hypothesize that the frequency of complications in CHIKV and ZIKV coinfections is comparable to that observed in CHIKV and ZIKV mono-infections. These complications may be due to individual patient factors that warrant further investigation and are beyond the scope of this study.

We rigorously screened over 300 individuals, ensuring strict patient selection to create well-matched groups to provide confidence in the robustness of our findings. Although, the rate of ZIKV and CHIKV coinfection in our cohort was 4%, three-times higher than the reported 1%3, studies of this nature are challenging and require the screening of many patients and strict selection criteria to produce meaningful data. Indeed, we recruited patients during an outbreak in a geographical region that is part of a cluster experiencing intense co-transmission of CHIKV and ZIKV19. This co-occurrence could lead to more intense transmission of both viruses, a phenomenon not clearly observed in other studies.

To our knowledge this is the first study to provide an extensive cytokine profile for CHIKV and ZIKV coinfected patients, showing that coinfection leads to an intermediate inflammatory profile between CHIKV and ZIKV monoinfections. A previous report evaluating eight cytokines and chemokines among patients with CHIKV and ZIKV coinfection and monoinfections found similarities among all groups, except that ZIKV-monoinfected patients exhibited more intense clinical manifestations20. Conversely, we observed that CHIKV infection triggered a robust immune response, upregulating eleven immune markers, while ZIKV infection resulted in a modest increase in only three immune mediators to lower symptomatology. This aligns with previously published data suggesting that CHIKV and ZIKV infections elicit robust and less robust immune responses, respectively21,22. However, it is necessary to emphasize that differences could be due to host genetic characteristics that lead to variations in the immune response. In this regard, our group has demonstrated that certain genetic characteristics in humans from the study population, when infected with arboviruses or other infectious and parasitic diseases, could lead to different disease progression and evolution5,23,24,25.

Indeed, it is well known that CHIKV proteins can interact with more host factors than ZIKV, which could contribute to a more diverse response to infection9, as observed in the present study. Therefore, it is possible that concomitant ZIKV and CHIKV infection leads to viral interference rather than synergy26, resulting in a more modest immune response, as previously observed by reduced viral loads in coinfections among CHIKV, DENV, and ZIKV27. Corroborating this, our results show that coinfected patients had a higher average Ct value for CHIKV detection than patients infected with CHIKV alone, which may indicate interference by ZIKV leading to a lower CHIKV viral load in concomitant infections. Furthermore, this viral interference and lower immune response could be related to similar clinical manifestations, with no severe cases and no worse prognosis observed in coinfected patients, as indicated by our results. However, more studies are necessary to clarify this, especially infection models that could determine whether there is interference between CHIKV and ZIKV.

As expected, CXCL10 levels were elevated in all groups, as this chemokine is upregulated by type I and II IFNs following viral infections and plays a key role in the pathogenesis of viral infections. This study corroborates previous finding of CXCL10 elevation during the acute phase of CHIKV and ZIKV infections28. Specific comparisons show that the coinfected and CHIKV groups displayed higher levels of CXCL10 than the ZIKV group, indicating a more robust inflammatory profile in these groups. However, despite previous associations of this cytokine with severe disease in arboviral infections29, severe cases were not observed in the present study.

Moreover, the CHIKV monoinfected group exhibited higher levels of IL-1RA, IFN-α, CCL2, and CCL4 than the other groups. These markers are linked to the acute antiviral response and are related to different prognoses of CHIKV, ZIKV, and other arbovirus infections30,31,32. However, additional analyses did not reveal a specific segregation of the immune response among the groups. ZIKV-infected patients exhibited a less intense immune response, primarily involving three chemokines present across all groups – CXCL10, CCL5, and CXCL1 – which have been previously associated with ZIKV infection33. These patients also exhibited higher levels of SCF, a growth factor released in inflammatory conditions and associated with the protection of the fetus in ZIKV-infected pregnant women34. Indeed, the enrichment analysis of protein–protein interactions revealed a more pronounced response of chemokine-mediated chemotaxis activity in patients with CHIKV monoinfection or coinfection, including neutrophil attraction, which could act as protection or lead to disease exacerbation35. Additionally, the pronounced presence of other pathways linked to cytokine and inflammatory responses in coinfected patients corroborates the elicited differential response in coinfection with CHIKV and ZIKV.

In conclusion, CHIKV and ZIKV coinfection resulted in mild clinical symptoms, similar to those seen in monoinfections, and presented a profile of circulating immune mediators more robust than ZIKV infection but more modest than CHIKV infection. Our study makes an important contribution to the limited research on coinfection and its impact on disease severity and host responses. We recognize the limitation in sample size of this study to draw strong conclusion, however, it provides valuable information regarding profiles of immune mediators produced during acute phase of CHIKV, ZIKV and coinfection with these viruses. The reported data adds to the field and to further studies on the pathogenesis of arboviruses infections and coinfections.

Materials And Methods

Ethics statement

The research was developed according to national guidelines and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Sergipe (protocol number 1.486.302). The participants provided written informed consent after receiving verbal information about the study.

Study design, sampling, and diagnostics

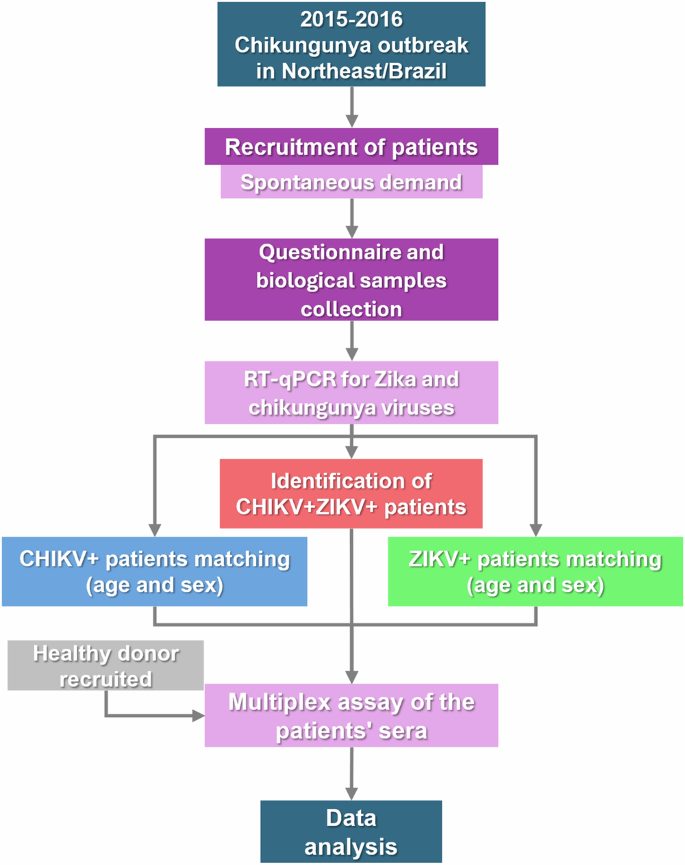

This research is a cross-sectional observational study involving patients with concomitant infections of chikungunya and Zika viruses. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and informed consent was obtained. Recruitment occurred throughout 2016 at the University Hospital of the Federal University of Sergipe. Participants were divided into one noninfected control group and three primary patient groups: the CHIKV monoinfected group, the ZIKV monoinfected group, and the Coinfected group (Fig. 4).

Timeline summarizing the study rationale and the steps of patient recruitment, blood collection, sample processing, data acquisition, and analysis.

All patients were adults who spontaneously reported to the hospital with signs and symptoms of arboviral infection. The selection criteria for inclusion in this study were based on positive qPCR results for CHIKV and/or ZIKV and patients who were symptomatic for less than 14 days. A total of 300 patients were screened by qRT-PCR using previously reported protocols and 38 participants were selected and divided into three groups: the CHIKV monoinfected group (n = 13), the ZIKV monoinfected group (n = 13), and the CHIKV and ZIKV coinfected group (n = 12). The control group (n = 13) consisted of well-matched noninfected individuals recruited based on the lack of clinical symptoms and a negative history of arboviral infection, who tested negative for IgG and IgM for both CHIKV and ZIKV.

Data were collected for all groups at the initial assessment included age, sex, duration and type of symptoms, including the presence of conjunctivitis, exanthema, fever, myalgia, lymphadenopathy, and retro-orbital pain. The frequency of treatment with analgesics, NSAID, antihistaminic, and antipyretic and diagnosis of comorbidities were also documented. Blood samples were collected from all participants during their initial visit and stored frozen until the assay execution.

The exclusion criteria were patients with cancer, or in chronic use of immune modulators, or those diagnosed with other inflammatory or infectious diseases. All patients included in this study achieved clinical cure without developing complications from the arboviral infection or requiring hospitalization.

Detection of chikungunya and Zika virus

Viral RNA was isolated from serum or plasma samples utilizing the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. Subsequently, reverse transcription followed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using the SuperScript® III Platinum® One-Step qRT-PCR System from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Specific primers and probes targeting chikungunya36 and Zika37 viruses were sourced from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, USA). Amplification was executed on an ABI 7500 FAST system (Applied Biosystems, USA). Samples yielding a cycle threshold (CT) value of 38 or below were classified as positive for either Chikungunya or Zika virus infection36.

Quantification of immunological mediators

The immune response markers were quantified using the ProcartaPlex™ Human Cytokine/Chemokine/Growth Factor Panel 1, 45plex kit (Thermo Fisher, USA). The analysis was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a Luminex® 100 system (Merck Millipore, USA). Results are expressed in picograms per milliliter (pg/mL). The following were the analytes studied: Th1/Th2: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon γ (IFN-γ), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-18, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α); Th9/Th17/Th22/Treg: IL-9, IL-10, IL-17A, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23, IL-27; Inflammatory cytokines: IFN-α, IL-1α, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), IL-7, IL-15, IL-31, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), Lymphotoxin α (LT-α or TNF-β); Chemokines: C-C motif chemokine ligand 11 (CCL11 or Eotaxin), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), CXCL10 (or IP-10), CCL2 (or MCP-1), CCL3 (or MIP-1α), CCL4 (or MIP-1β), CCL5 (or RANTES), CXCL12 (or SDF-1α); Growth factors: brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), nerve growth factor β (β-NGF), platelet derived growth factor subunit B (PDGF-BB), placental growth factor 1 (PIGF-1), stem cell factor (SCF), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), VEGF-D.

Data processing and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9 and R version 4.3. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05 in a two-tailed analysis. The STROBE guidelines were followed to construct this report (checklist v4)38. For categorical variables, Pearson’s chi-squared test, followed by post-hoc analysis, was employed to identify differences among groups, using the ‘chisq.posthoc.test’ package in R.

For continuous numerical data, the normality of the data was first assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Subsequently, the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s test with adjustments for multiple comparisons, was used to compare groups. For selected immune mediators, volcano plots were generated by plotting the log2 fold change against the negative log10 p-value for each comparison. Additionally, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed and plotted using the ‘ggfortify’ package. To understand the relationships among immune mediators, correlations were calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation (rho) and plotted using the ‘corrplot’ package. Furthermore, analysis of protein–protein interactions and biological enrichment was performed using STRING39.

Responses