Comparative analysis of endoscopic discectomy for demanding lumbar disc herniation

Introduction

Lumbar disc herniation (LDH) is a clinical condition manifested by symptoms such as low back pain, radiating pain along the sciatic nerve, and, in severe cases, cauda equina syndrome. It affects an estimated 1–3% of the general population annually1. When the nucleus pulposus protrudes through the posterior longitudinal ligament, the likelihood of displacement significantly increases, resulting in intervertebral disc fragment displacement in 35–72% of cases2. High-grade down-migrated lumbar disc herniation (HDM-LDH) is a rare type of lumbar disc herniation, in which the intervertebral disc is displaced downward to below the midpoint of the pedicle3. Studies have reported that the incidence of HDM-LDH accounts for about 23% of translocated LDH4. Previous studies have demonstrated that the direction of disc migration is influenced by both the disc level and patient age. Discs located at the upper lumbar levels exhibit a higher tendency for upward migration, while those at the lower lumbar levels show a greater propensity for downward migration. Additionally, as age advances, the likelihood of lumbar disc displacement increases, although the incidence of downward displacement decreases5,6. When the intervertebral disc protrudes downward, it can compress the nerve roots or cauda equina, leading to general symptoms such as pain, numbness, and sensory and motor dysfunctions, or even paralysis. This condition is more harmful than typical LDH7.

When herniated disc fragments are proximal to the originating disc, therapeutic intervention is relatively straightforward. However, as the extent of displacement escalates, the complexity of treatment correspondingly increases5. When patients with HDM-LDH do not respond to conservative treatment or when the effect of such treatment is unsatisfactory, surgical intervention can significantly improve symptoms. Previous studies have demonstrated that fully endoscopic lumbar discectomy has a high failure rate in cases of severe disc displacement, thus open lumbar discectomy or lumbar fusion with internal fixation is often recommended8. However, open surgery necessitates the dissection of paraspinal muscles and the removal of lamina and facet joints, which may result in spinal motion segment instability and persistent lower back pain9. With the advancement of minimally invasive surgical techniques, unilateral biportal endoscopic (UBE) discectomy and percutaneous interlaminar endoscopic lumbar discectomy (IELD) have emerged as new options for clinicians. Both procedures offer advantages in terms of postoperative recovery, skin incision length, muscle damage, infection rate, surgical pain, and hospitalization time. Notably, the success rates of these operations have improved10. Several studies have compared the efficacy of two surgical procedures for treating LDH, but their effectiveness in treating HDM-LDH remains undetermined. This study involved 39 patients with HDM-LDH as observation subjects, comparing and analyzing the clinical efficacy of UBE and IELD. The findings offer novel insights into the treatment of HDM-LDH.

Materials and methods

Demographic data

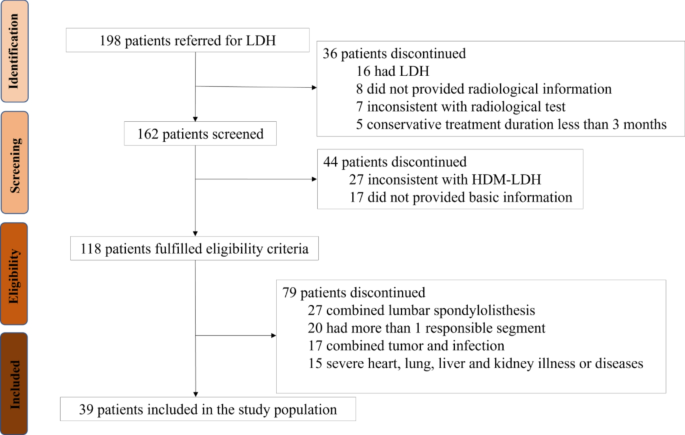

A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients who underwent UBE or IELD surgery for HDM-LDH at the Department of Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, from January 2020 to February 2023. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study, the UBE group comprised 18 cases, while the IELD group consisted of 21 cases, totaling 39 cases (see Fig. 1 for the screening process). The preoperative basic data of both groups were compared, and the indicators were found to be comparable (Table 1). This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (approval number: JY2024-120). Informed consent from patients was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study design. All research procedures adhered to pertinent guidelines and regulatory standards. The surgeons in both groups held equivalent qualifications.

Flowchart of study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) preoperative imaging revealed a single-segment LDH with significant downward displacement, and there was no prior history of LDH; (2) clinical manifestations were consistent with radiological findings, presenting with pronounced low back pain and radiating pain in the lower extremities. Conservative treatment for three months proved ineffective; (3) follow-up extended for at least three months post-treatment.

Exclusion criteria: (1) concurrent lumbar spondylolisthesis, instability, or other conditions that could cause low back and leg pain; (2) more than one responsible segment or a history of lumbar surgery on the same segment; (3) concurrent tumors, infections, and other lesions; (4) a history of severe underlying diseases; (5) patients unfit for anesthesia.

Surgical method

UBE group

The patients were positioned prone under general anesthesia. C-arm fluoroscopy was employed preoperatively to identify the targeted intervertebral space and determine the needle insertion site. The target intervertebral space was located 1.5 cm lateral to the spinous process, approximately at the medial edge of the vertebral arch. A puncture needle was introduced along the paramedian line on the affected side, 1 to 1.5 cm above and below the midline of the target intervertebral space, serving as both the observation channel incision and the operational channel incision, with a distance of 2.5 to 3.0 cm between the two incisions. For the right-sided approach, the cranial end served as the operational port, while the caudal end functioned as the endoscopic observation port; the left-sided approach followed the reverse configuration. Under fluoroscopic guidance, two guide rods were inserted into the entry points and intersected at the junction of the spinous process and lamina of the superior vertebra. The soft tissue was gradually expanded using a dilator, and both the endoscopic cannula and working cannula were positioned. The endoscope system was then connected. Once the field of view under water perfusion was clear, radiofrequency ablation and forceps were employed to clean the soft tissue within the field of view. This process exposed the lower edge of the superior lamina and the upper edge of the inferior lamina. A drill and rongeurs were used to separate the yellow ligament at the cephalic end and remove part of the vertebral lamina bone from the caudal end until the nucleus pulposus prolapsed. Subsequently, the yellow ligament was separated from the dura mater. The yellow ligament was gradually removed to expose the dura mater sac and nerve roots, and the free nucleus pulposus was separated from the nerve roots while protecting the dura mater sac and nerve roots. The prolapsed nucleus pulposus tissue was progressively removed. Throughout the entire operation, vigilant attention was paid to bleeding control and hemostasis. After complete decompression of the nerve root, the working cannula was removed, a drainage tube was placed, and the incision was sutured and bandaged.

IELD group

The patient was positioned prone under general anesthesia. C-arm fluoroscopy was utilized to identify the responsible intervertebral space and determine the needle insertion site preoperatively. A 1.0 cm incision was made lateral to the spinous process, and the puncture needle was used to penetrate the outer edge of the interlaminar space layer by layer. Once the position was confirmed via fluoroscopy, a guide wire was inserted. An 0.8 cm skin incision was then made, and the soft tissue was progressively dilated using a dilator before inserting a working cannula. The entire surgical procedure was conducted under real-time visualization and continuous irrigation with isotonic saline solution. The bone at the superior and inferior edges of the interlaminar space was meticulously exposed, followed by the removal of the yellow ligament situated between the vertebral laminae. A grinding drill and bone rongeurs were employed to excise the caudal portion of the vertebral lamina at the distal end, thereby exposing the traversing nerve roots and the prolapsed intervertebral disc. Subsequently, the extruded nucleus pulposus was carefully dissected away from both the nerve roots and the dural sac. This herniated material was progressively extracted in a controlled manner to alleviate neural compression. Throughout the operation, vigilance was maintained to address any bleeding sites promptly, ensuring adequate hemostasis. Upon completion, the working cannula was removed, the incision was sutured, and a bandage was applied.

Perioperative management

Post-surgery, conventional symptomatic treatments, including analgesia, were administered. In the UBE group, if the drainage volume was less than 50 mL within 24 h, the drainage tube could be removed. Absent any significant discomfort, both the IELD and UBE groups were permitted to ambulate with protective gear the day following surgery. To assess postoperative recovery, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were conducted within 3 days after the procedure.

Observation indicators

The two patient groups were compared based on hemoglobin (Hb) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels preoperatively and postoperatively, intraoperative blood loss, duration of surgery, length of hospital stay, and incidence of complications. Pain severity in the back and legs, as well as limb dysfunction, were assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS) and the Oswestry disability index (ODI) at four time points: prior to surgery, one day post-surgery, one month post-surgery, and three months post-surgery. Patient satisfaction with clinical outcomes was gauged through the modified MacNab criteria, which categorized results into four tiers: excellent, good, fair, and poor, with ‘excellent’ denoting complete satisfaction. This assessment was conducted at a follow-up interval of three months post-surgery.

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26.0 software. For normally distributed measurement data, results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation ((:stackrel{-}{x})±s). Inter-group comparisons of such data employed an independent samples t-test, while within-group comparisons at each time point utilized variance analysis. Non-normally distributed measurement data were expressed using median and interquartile range (M [P25, P75]), with inter-group comparisons conducted via the two-sample rank sum test. Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square (χ²) test. Statistical significance was determined (P < 0.05).

Results

Perioperative outcomes and complications

Compared to the UBE group, the IELD group exhibited a shorter operative duration, reduced hospital stay, and less intraoperative blood loss, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). However, there were no statistically significant differences in the reduction of Hb levels or the increase in CRP levels (P > 0.05). No complications such as nerve root injury, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, epidural hematoma, or dural tear occurred in the UBE group, nor did any patients experience worsening conditions or require reoperation. Conversely, one patient in the IELD group experienced postoperative neurological symptoms, aggravated limb numbness, and decreased dorsiflexor muscle strength. See Table 2 for details.

Clinical indicators

Comparison of VAS scores between the two groups

Postoperatively, both groups showed significant reductions in VAS scores for low back and leg pain compared to preoperative levels. One day after surgery, the VAS score for low back pain was higher in the UBE group than in the IELD group (P < 0.05). However, there were no statistically significant differences in the VAS scores for low back pain and lower limb pain at one and three months postoperatively between the two groups (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 3.

Comparison of ODI scores between the two groups of patients

Postoperatively, both groups exhibited a significant reduction in ODI scores compared to their preoperative levels (P < 0.05). However, no statistically significant differences were observed in ODI scores between the two groups at one day, one month, and three months following surgery (P > 0.05), as illustrated in Table 4.

Improved MacNab criteria for evaluation of excellent and good rates

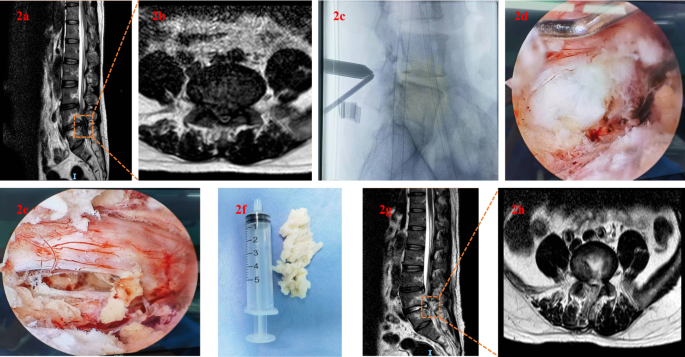

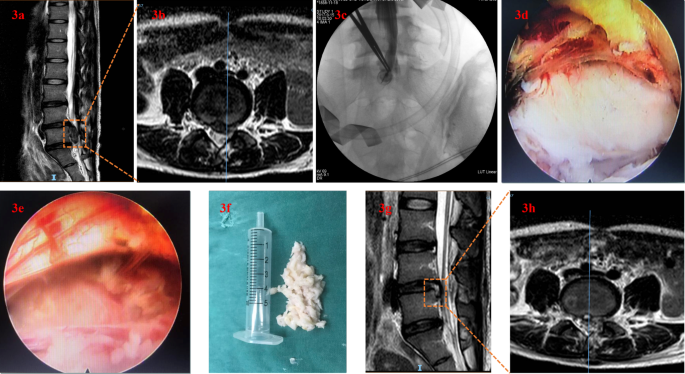

Follow-up was conducted three months post-surgery. In the IELD group, there were 20 cases classified as excellent and good, representing 95.24% of the total. In the UBE group, 17 cases were classified as excellent and good, accounting for 94.44%. The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 5. Representative cases are illustrated in Figs. 2 (UBE) and 3 (IELD).

UBE. (a–b) preoperative MRI demonstrated significant findings in both sagittal and transverse planes. Specifically, there was evidence of L5/S1 HDM-LDH, accompanied by pronounced compression of both the dural sac and adjacent nerve roots;(c) intraoperative lateral lumbar spine X-ray; (d–f) the microscope revealed a significant herniation of the nucleus pulposus. Following UBE treatment, nerve compression was alleviated;(g–h) postoperative MRI follow-up demonstrated complete removal of the herniated nucleus pulposus, with a satisfactory decompression outcome.

IELD. (a–b) preoperative lumbar MRI demonstrated the presence of HDM-LDH at the L4/L5 level, exhibiting severe nerve root compression in both sagittal and transverse planes;(c) intraoperative lateral lumbar spine X-ray;(d–f) upon microscopic examination, a hill-shaped herniation of the nucleus pulposus was observed. Following IELD therapy, the compression exerted on the dural sac was alleviated;(g–h) postoperative MRI follow-up revealed the resolution of the herniated nucleus pulposus, with evidence of effective neural decompression.

Discussion

LDH can induce radiating pain and paresthesia as a consequence of nerve compression and inflammatory responses. This condition may weaken the muscles innervated by the affected nerves, thereby impairing motor function. Consequently, the reduced physical activity stemming from LDH adversely impacts both the patient’s employability and overall quality of life. Beyond the direct psychological toll on the individual, prolonged treatment necessitates substantial financial expenditures, imposing an economic strain on the patient’s household11,12. When non-surgical interventions prove ineffective, common surgical approaches for LDH encompass open fixation, open simple nucleotomy, microscopic nucleotomy, and endoscopic nucleotomy1.

With the advancement of various surgical techniques, common surgical options for treating LDH have evolved accordingly. Early scholars advocated for open discectomy as the primary treatment for highly displaced LDH. However, since Kambin introduced the concept of the “safe triangle”, percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy has emerged as a prevalent surgical option among physicians. This minimally invasive procedure has an efficacy rate comparable to that of open surgery, reaching up to 90%, and encompasses three distinct approaches: transforaminal, interlaminar, and contralateral transforaminal13,14. Previous research has established the viability of percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal lumbar discectomy in addressing far-migrated LDH; however, this procedure is associated with a notably high failure rate ranging from 5–22%15. Ruetten initially introduced the IELD technique in 2006. The IELD procedure combines the benefits of conventional fenestration discectomy with advanced endoscopic technologies, leveraging the sublaminar corridor for comprehensive visualization of the extruded nucleus pulposus while minimizing excessive removal of the lamina and facet joints. This approach not only conserves the integrity of paraspinal musculature but also mitigates harm to osseous structures, thereby preserving the functional stability of the spinal motion segment16,17. Nonetheless, the integration of the operating channel within the single-port endoscope necessitates the use of instruments that are both more slender and elongated compared to their conventional counterparts. This deviation in instrumentation profoundly alters the surgical approach, demanding heightened technical proficiency from the surgeon and entailing an extensive period of skill acquisition18. From an anatomical standpoint, direct visualization of the distal free nucleus pulposus is challenging due to obstructions posed by the facet joints and pedicles. This issue is exacerbated when severely displaced intervertebral discs fragment into multiple pieces. Consequently, traditional percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy often falls short in treating HDM-LDH because of a limited field of view, inadequate exposure, and the technical difficulty in grasping these remote fragments9. Consequently, clinicians have shifted their focus toward the burgeoning UBE technology. The double-hole endoscope technique was initially introduced by Antoni in 1996 and has undergone continuous enhancements to evolve into the contemporary UBE technique19. From an instrumentation perspective, UBE can utilize conventional arthroscopes and microsurgical tools to perform the procedure, eliminating the need for a specialized single-port endoscope system and its accompanying surgical instruments. Since the distal operating channel of UBE is not constrained by a rigid working cannula, traditional larger surgical instruments can also be employed. Additionally, the endoscope is separate from the surgical instrument channel, which enhances mobility and provides a more comprehensive visual field, thereby facilitating easier grasping of the distal free nucleus pulposus. For novice surgeons, the surgical pathway and decompression process are analogous to those of conventional microdiscectomy, resulting in a relatively short learning curve18,20.

This investigation revealed that patients undergoing IELD experienced reduced intraoperative hemorrhage, abbreviated surgical durations, and expedited hospital discharges. This advantage can be attributed to the minimally invasive nature of IELD, wherein the establishment of the operative corridor involves less aggressive muscle dissection compared to UBE, thereby minimizing tissue trauma. Specifically, UBE necessitates blunt muscle spreading via dual channel creation for access, leading to heightened tissue disruption. Moreover, during the exposure of the herniated nucleus pulposus in a caudal direction, partial resection of the lamina is undertaken, inducing minor osseous bleeding. Postoperatively, the insertion of a drainage tube mandates monitoring of wound exudate, prolonging both surgical duration and convalescence period21. The IELD procedure involves inserting a cannula into the interlaminar space through a single access point. This approach allows for a direct incision of the yellow ligament, thereby exposing the nerve root with minimal tissue damage and reduced bleeding. Additionally, this technique facilitates shorter hospital stays as it obviates the need for a drainage tube to monitor effluent22. In Wang’s study, postoperative serum creatine kinase levels and the ratio in the UBE group were higher compared to those in the IELD group. Additionally, postoperative MRI examinations revealed that the cross-sectional area of high-signal lesions in the paraspinal muscles was smaller in the IELD group than in the UBE group, suggesting that IELD is less invasive and causes less muscle damage than UBE23. Perioperative anemia not only elevates the risk of postoperative infections and prolongs hospitalization but also significantly impairs postoperative activity levels and functional recovery. However, the comparison of Hb decrease values did not reveal statistical significance (P > 0.05), and no adverse reactions associated with anemia were observed post-surgery, suggesting that the total blood loss in both groups was minimal.

In the intra-group comparison, the VAS scores for low back pain and leg pain demonstrated a downward trend. In the inter-group comparison, the IELD group exhibited lower VAS scores for low back pain at one day post-surgery; however, the VAS scores for low back pain and leg pain at other time points were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The ODI scores within each group were compared, revealing that both groups had significantly lower ODI scores post-surgery compared to baseline (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in ODI scores between the two groups at one day, one month, and three months post-surgery (P > 0.05). Additionally, the comparison of the excellent and good rates according to the MacNab standard between the two groups at three months post-surgery was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). These results suggested that both groups had similar clinical efficacy in terms of functional improvement. Since the inflammatory response is closely related to pain, the lack of a significant difference in CRP increase values between the two groups (P > 0.05) indicates a similar degree of inflammatory response. This analysis may be influenced by factors such as the surgeon’s proficiency, the precision of the operation, and postoperative medication.

In this study, one patient in the IELD group developed neurological symptoms postoperatively, which required rehabilitation and outpatient follow-up. Although the incidence of complications was low, preventive measures should still be implemented. Common intraoperative complications included dural tears (0.18%) and nerve root injuries (0.55%). Postoperative complications comprised weakness (0.92%), limb numbness (3.3%), and incomplete disc removal (0.18%)24. Maintaining optimal water pressure during surgery not only helps to control bleeding at the surgical site but also effectively minimizes dural expansion, thereby creating a safe distance between the dura mater and the yellow ligament. This reduces the risk of inadvertent dura mater injuries. Should a tear in the dura mater be detected postoperatively, it must be repaired via suturing or the use of a fibrin patch, depending on the specific circumstances25,26. Furthermore, persistent irrigation with isotonic saline serves to eliminate locally secreted pro-inflammatory mediators during surgical procedures, thereby mitigating the likelihood of regional inflammatory responses and alleviating postoperative pain experienced by patients27,28. Postoperative neurological symptoms, such as paresthesia, may be attributed to irritation of the spinal ganglia or nerve roots during the surgical procedure. The use of bipolar coagulation and repeated compression within the working channel can also contribute to postoperative dysesthesia15. When the intraoperative exploration range is insufficient, intervertebral disc residue may occur. Therefore, while expanding the exploration range as much as possible, care should be taken to minimize stimulation of the nerve roots.

In terms of procedural application, IELD typically involves initially staining the protruding nucleus pulposus followed by its removal. During ligament sectioning, employing basket forceps and lamina rongeurs to create a transverse incision outward facilitates clear exposure of critical anatomical structures, including the dura mater sac, nerve roots, and the protruding nucleus pulposus. Utilizing the lingual surface of the working sleeve for rotation and forward pressure to shield the nerve root, the sleeve’s rotation typically spans from the nerve root’s distal extremity towards its proximal end. In cases of inferiorly displaced intervertebral disc herniations, UBE adopts the Corner angle technique to disengage the superior margin of the lamina’s yellow ligament terminus and excise a portion thereof, with no need to reveal the cranial aspect of said ligament. Subsequent steps entail utilizing a burr and rongeurs to excise a segment of the caudal lamina, thereby unveiling the distal extremity of the descending nucleus pulposus. Post-removal of the entire protrusion, intervertebral space decompression is executed.

This study has several limitations: (1) the data were sourced from a single center, resulting in a small sample size; (2) surgeons exhibited varying levels of proficiency in the two surgical procedures; (3) the follow-up period was short, and no long-term postoperative effects were investigated; (4) both surgical techniques are destructive to the lumbar vertebral bone structure, necessitating further comparison and evaluation of postoperative lumbar segment stability. These issues will be addressed in future research.

In conclusion, both UBE and IELD demonstrate efficacy in treating HDM-LDH, markedly alleviating symptoms of lower back pain, leg discomfort, and enhancing patient mobility. However, the IELD cohort exhibited advantages such as reduced intraoperative hemorrhage, abbreviated hospitalization durations, and a minimally invasive approach. Conversely, UBE offers enhanced flexibility in surgical maneuverability alongside a distinct decompressive impact. Given these findings, clinicians are advised to tailor their therapeutic selection to individual patient circumstances. Nonetheless, it is imperative to acknowledge that due to the constraints imposed by the limited sample size and brief follow-up period inherent to this retrospective investigation, there remains a necessity for comprehensive, multi-institutional, large-scale prospective trials to definitively assess and compare the long-term outcomes and overall efficacy of UBE versus IELD in managing HDM-LDH.

Responses