Comparison of stimulation sites enhancing dual-task performance using transcranial direct current stimulation in Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

As the global population continues to age, Parkinson’s disease (PD) has arisen a major neurological condition, contributing significantly to the global burden of disease1. PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder caused by dopamine deficiency due to the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta2. The hallmark motor symptoms of PD include bradykinesia, rigidity, tremors, and postural instability3. Additionally, non-motor symptoms, such as cognitive impairment, depression, sleep disturbances, and autonomic dysfunction, are also common4. Pharmacotherapy is the cornerstone of PD treatment, with levodopa being the standard treatment for alleviating symptoms by replenishing dopamine levels5. However, despite optimal pharmacological management, most patients with PD inevitably experience functional impairments. As such, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic strategies to delay or restore functional deficits in patients with PD.

Noninvasive brain stimulation techniques offer safe, inexpensive, and easy-applicable methods6. Notable examples include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial alternating current stimulation, and direct current stimulation (tDCS). Of these, tDCS delivers a direct current through electrodes placed on the scalp, thereby changing the polarity of the neuronal membranes of the cerebral cortex, which may either increase or decrease cortical excitability7. Numerous studies have previously demonstrated the efficacy of tDCS in enhancing mood and cognitive functions such as working memory and attention following stimulation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in patients with major depressive disorder and schizophrenia8,9. Additionally, research involving tDCS in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease has revealed improvements in verbal and visual memory recognition10,11. In the field of rehabilitation, tDCS has been used to aid recovery from motor and speech impairments caused by neurological deficits following stroke12,13.

Several studies have also investigated the utility of tDCS in alleviating various symptoms in patients with PD. For example, anodal tDCS over the primary motor cortex (M1) in patients with PD has been shown to have beneficial effects on gait, freezing of gait, and motor function14. Postural responses have also improved following eight sessions of bilateral M1 stimulation15. Furthermore, bilateral M1 tDCS in PD exerts an immediate beneficial effect on tremor suppression by modulating the interhemispheric imbalance in cortical excitability, which contributes to tremor genesis16. The application of tDCS to the motor and prefrontal cortices has further been shown to improve the 10-meter walk speed and reduce bradykinesia in patients with PD17. Meanwhile, multitarget tDCS over M1 and DLPFC has been shown to improve freezing of gait, although only M1 stimulation failed to demonstrate these effects18. To enhance cognitive function, including working memory and executive function, in PD, several studies have investigated stimulation of the DLPFC19,20,21. Anodal stimulation of the DLPFC has also demonstrated positive effects on depression, a common nonmotor symptoms of PD22. In addition, cerebellar tDCS has been explored as a method to potentially improve balance in patients with PD, with some studies reporting beneficial outcomes in terms of postural control and gait stability23. Other studies have indicated that anodal tDCS targeting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and cathodal over the DLPFC could affect deep brain regions with dopaminergic neurons, which were considered unreachable using noninvasive stimulation methods24. Furthermore, the vmPFC, along with the DLPFC, is known to play a central role in the processing of cognition and emotion. It is primarily involved in functions such as evaluating the value of stimuli, decision-making, and self-based evaluation25. Anodal tDCS over the vmPFC has been shown to significantly reduce arousal attribution to emotional stimuli and enhance emotional regulation, particularly in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders25,26. This approach may represent a promising intervention in patients with PD.

In the early stages of PD, dysfunction of the sensorimotor areas of the basal ganglia leads to impairments in habitual control27. Consequently, cognitive effort is required to perform habitual motor tasks, such as walking, which reduces dual-task performance and affects gait automaticity. This reduction in dual-task performance increases the risk of falls among patients with PD28. Few studies have previously explored the effects of tDCS targeting the M1, DLPFC, or bilateral DLPFC in improving dual-task gait speed and reducing dual-task interference in patients with PD29,30,31. However, the rationale and effects of tDCS on dual-task performance in patients with PD remain unclear. The stimulation sites, frequency and duration of application, use of the cathode or anode, and evaluation methods vary across studies. Therefore, we hypothesize that tDCS applied to different brain regions will have varying effects on motor and cognitive functions, potentially enhancing dual-task performance in patients with PD. This study aimed to investigate and compare the effects of different stimulation sites on dual-task performance in patients with PD using tDCS, with the goal of identifying the most effective stimulation site.

Results

A total of 24 patients were screened and enrolled in this study, of whom 20 completed all four sessions successfully, and 4 withdrew consent during the study. One participant was diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy following neurological clinical evaluation after the study and was therefore excluded from the final analysis. Consequently, the results of 19 participants were analyzed. Two participants were unable to perform the trail-making test (TMT) Trail B due to cognitive decline; as such, the Trail B results were analyzed based on the remaining 17 participants. As an adverse event, one participant reported nausea following the stimulation; however, it was mild and resolved within a day.

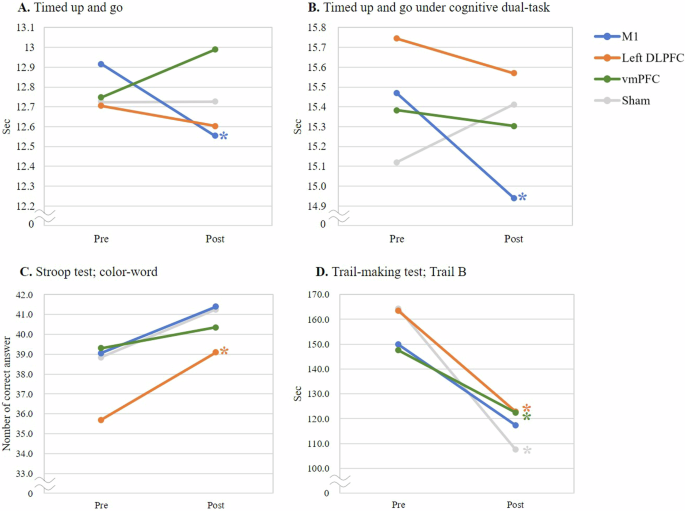

The participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Overall, we observed no statistically significant time-by-group interactions in the timed up and go (TUG) test or dual-task effects (DTEs) by generalized estimation equation (GEE) (Supplementary Table 1). Although we observed significant time effects on the word test (χ2 = 6.666, p = 0.010), color test (χ2 = 9.791, p = 0.002), color-word test (χ2 = 9.897, p = 0.002), TMT Trail A (χ2 = 5.149, p = 0.023), Trail B (χ2 = 20.070, p < 0.001), and Digit span forward test (χ2 = 4.584, p = 0.032), we did not observe any significant time-by-group interactions. Table 2 presents the changes in clinical outcome variables before and after stimulation. Stimulation of the M1 significantly reduced the TUG time from 12.92 ± 4.16 to 12.55 ± 3.88 s (p = 0.028), while also significantly decreasing the cognitive dual-task TUG time from 15.47 ± 5.48 to 14.94 ± 4.97 s (p = 0.044). Anodal tDCS over the DLPFC induced significantly improvements in the color-word test from 35.79 ± 11.25 to 39.05 ± 11.27 (p = 0.013). The TMT Trail B was significantly enhanced following DLPFC, vmPFC, and sham stimulation (p = 0.017, 0.035, and 0.017, respectively) (Fig. 1).

A Timed up and go test. B Timed up and go test under cognitive dual-task condition. C Stroop test (color-word test). D Trail-making test, Trail B. Each data point represents the group mean. *p < 0.05, indicating a significant difference between pre- and post-stimulation within the group.

For subgroup analysis, the TUG test results before and after stimulation were analyzed in 15 participants with Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stages 2 and 2.5 (Table 3). The cognitive dual-task TUG time was significantly reduced following left DLPFC stimulation (p = 0.041), while the single-task TUG time was significantly reduced following M1 stimulation (p = 0.035). The TUG results, categorized according to the presence of freezing of gait, indicated that freezers consistently exhibited longer TUG times than non-freezers. This difference was particularly notable during physical dual-task performance. Among non-freezers, anodal left DLPFC stimulation resulted in a statistically significant decrease in TUG time under cognitive dual-task conditions, from 15.81 ± 2.51 to 14.83 ± 2.84 s (p = 0.014) (Table 4).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the most effective tDCS stimulation sites to enhance dual-task performance in patients with PD. Overall, our results indicated that stimulating the M1 significantly improved TUG times under both single-task and cognitive dual-task conditions. Anodal stimulation of the left DLPFC led to significant improvements in the executive function. However, none of the stimulation sites resulted in significant changes in the DTE. Subgroup analysis further indicated that left DLPFC stimulation reduced cognitive dual-task TUG times in certain subgroups, such as those with H&Y stages 2 and 2.5, and in non-freezers. Additionally, although not statistically significant, we observed a tendency for cognitive DTE to decrease with all real stimulations except sham stimulation in the H&Y stage 2 and 2.5 group.

Similar to our study, another study also compared the effects of tDCS between stimulation targets, including the M1, left DLPFC, cerebellum, and sham stimulation, to improve dual-task walking performance in PD32. The results of this prior study indicated that stimulation of the left DLPFC improved performance in the 10-meter walk test with a cognitive dual-task compared with sham stimulation. Among the secondary outcomes, the TUG test results did not identify the most effective stimulation site that improved performance, which is consistent with our study results. Among patients with PD, straight walking showed little difference in dual-task performance compared with healthy controls33. However, significant differences were observed when performing functional ambulation tasks that include turning or curved gait, such as the TUG test, figure-of-eight walk test, or Three-Meter Backward Walk Test33. As approximately 30% of walking in daily life occurs in complex environments like curved walking, it is advisable to evaluate and improve dual-task performance in PD patients within environments that could provide a variety of walking tasks34.

Overall, our results indicated that M1 stimulation significantly decreased TUG time under both single-and cognitive dual-task conditions. Several studies have previously reported that tDCS over the M1 enhances motor performance35. tDCS of the M1 influences the targeted cortical area and achieves indirect modulation through cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loops36. However, this improvement did not appear to be directly related to the reduction in DTE. Dual-task performance further involves a complex interaction of many factors, including the motor phenotypes of PD, such as rigidity, tremor, and bradykinesia, and cognitive functions such as executive function, attention, and set shifting37. Therefore, rather than improving a specific function, a more comprehensive approach may be required to enhance dual-task performance.

tDCS over the DLPFC has been investigated to improve dual-task gait performance30,31. The left DLPFC is involved in the management of cognitive resources for dual-task performance38. Previous functional near-infrared spectroscopy studies have shown increased activation of this area during the dual-task gait38. Anodal DLPFC stimulation can enhance the dual-task gait speed and dual-task interference among patients with PD30,32. Nevertheless, our results indicate that there were no significant changes in the TUG results with left DLPFC stimulation, despite an increased executive function. Similar to our research, other studies have also found that DLPFC stimulation did not induce changes in TUG results, although some studies have reported that DLPFC stimulation improved the dual-task effect or cognitive performance under dual-task conditions31,39. These findings indicate mixed results regarding the efficacy of tDCS over the DLPFC. In our study, subgroup analysis suggested that cognitive dual-task performance improved with DLPFC stimulation in patients with H&Y stages 2 and 2.5, as well as in non-freezer patients. Therefore, the characteristics of the study population may be one of the reasons explaining these mixed results. Various factors may contribute to the differences in the effects of tDCS, including inter-individual variability (such as anatomical features, age, or sex), intra-individual variability (such as hormonal variation or substance use), and contextual features40. For example, even when applying tDCS using the same montage based on the international 10–20 electroencephalography system, anatomical differences between individuals may result in varying current densities at the targeted sites, leading to inconsistent results41. Future studies are warranted to investigate the effects of personalized tDCS, based on the functional and anatomical aspects of patients with PD.

Our results indicated that positive effects of tDCS were not observed in freezers, whereas non-freezers showed improvements. A recent meta-analysis investigating the effects of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) on freezing of gait (FoG) in PD reported no significant improvement in the TUG test following NIBS application42. This finding aligns with our results, and these findings may be attributed to the underlying neural mechanisms associated with FoG. Freezers exhibit alterations in the functional connectivity and topological properties of specific brain regions, such as decreased nodal centrality in the left middle frontal gyrus, which reflects disrupted regional topological organization and may contribute to the pathophysiology of FoG43. These findings suggest that addressing such complex network disruptions may require alternative tDCS protocols or stimulation parameters to achieve meaningful improvements in patients with FOG.

This study has several limitations. First, as this was a pilot study, the sample size was small, and the crossover design involved repeated measures, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, conventional tDCS, which does not reflect individual variability, was used. Despite limiting the functional level of the patients through the inclusion criteria, inter-individual differences may have affected the significance of the results, as shown by the subgroup analysis. Third, we compared the effects of single-session stimulation across various targets to identify optimal stimulation sites. Assessments were conducted repeatedly before and after the stimulation. This protocol may lead to underestimated effects of tDCS due to participant fatigue44 or overestimated results if participants adapt to the assessment tasks over time. Furthermore, although the observed changes in our study were statistically significant, the effect sizes were relatively small. To strengthen the synaptic connections and maintain these effects, repeated applications may be necessary to achieve cumulative effects45. Repeated stimulation sessions could potentially lead to clinically meaningful changes. Lastly, combining tDCS with other training modalities, such as dual-task walking or aerobic exercise, has been reported to yield significant improvements in motor and cognitive symptoms of PD46,47. Future research exploring the integration of tDCS with concurrent tasks would be valuable in determining whether this combined approach offers greater benefits compared to single interventions.

In conclusion, tDCS over the M1 may enhance motor performance, and stimulation of the DLPFC may improve cognitive performance, although we could not establish the superiority of any specific stimulation site. Despite these findings, none of the stimulation sites demonstrated significant effects on dual-task interference. Further research is needed required to explore alternative stimulation approaches based on patient functional levels, or to verify the cumulative effects of repeated tDCS sessions.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective, single-center, double-blind, explorative, pilot randomized crossover trial. The protocol for which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. 2003-221-1114) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04504422). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age > 19 years, (2) clinical diagnosis of idiopathic PD according to the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank Diagnostic Criteria, and (3) modified H&Y stages of 2, 2.5, or 3. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of seizure; (2) metallic implants, such as cardiac pacemaker or an artificial cochlea; (3) inflammation, burns, or wounds in the stimulation area; (4) diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease dementia based on the Korean Montreal Cognitive Assessment (K-MoCA) test, with the following cutoff scores48: < 7 points: Illiterate, < 13 points: Education duration 0.5–3 years, < 16 points: Education duration of 4–6 years, < 19 points: Education duration of 7–9 years, and < 20 points: Education duration 10 years or more; (5) severe dyskinesia or severe on-off phenomenon; (6) plan to adjust medication at the time of screening; (7) sensory abnormalities of the lower extremities, other neurological or orthopedic disease affecting lower extremities, or severe cardiovascular diseases; (8) vestibular disease or paroxysmal vertigo; (9) pregnant or lactating patients; and (10) other comorbidities that make it difficult to participate in this study.

Participants were recruited from an outpatient clinic at Seoul National University Hospital between November 2020 and January 2024, with the last follow-up date on February 13, 2024. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants by the physicians involved in the study. Evaluations and interventions were conducted in the “on” state, representing the peak effect of PD medication. Each participant was required to visit the hospital during a time when their physical condition was optimal after taking their first dose of medication for the day. To ensure consistency in the participants’ condition, both the time of the first medication dose and the start of the study were kept constant. Throughout the study, the dosage of anti-parkinsonian medications was kept constant for all participants.

Intervention

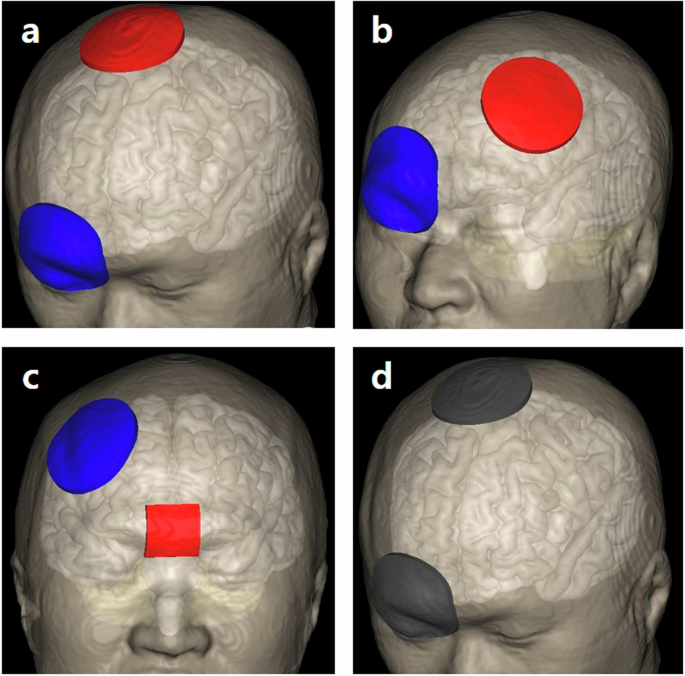

The participants underwent four sessions, each of which involved the application of anodal tDCS randomly assigned to the M1, left DLPFC, or vmPFC, or sham stimulation (Mindd Stim; Ybrain, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) (Fig. 2). All possible permutations in the four stimulation methods were generated, yielding 24 unique sequences. These sequences were then independently generated and randomly shuffled by a third party not involved in the study, and each participant was assigned to a sequence based on their order of enrollment. For M1 and sham stimulation, the anodal electrode was positioned over Cz according to the international 10–20 electroencephalography system, while the cathodal electrode was placed on the right orbital frontal cortex (Fp2). For left DLPFC stimulation, the anodal electrode was placed at the F3 position, with the reference electrode positioned at Fp2. Additionally, when targeting the vmPFC, the anodal electrode was placed over the Fpz, while the cathodal electrode was placed on the right DLPFC (F4)24. The stimulation intensity was set to 2 mA for 20 min. During the real stimulation, the current was ramped up to 2.0 mA over a period of 30 s, maintained at 2.0 mA for 19 min, and then ramped down to 0 mA over the final 30 s. For the sham stimulation, the current was ramped up to 2.0 mA during the first 30 s, ramped down to 0 mA over the next 30 s, and then no current was supplied for the remaining 19 min. A washout period of at least 7 days was implemented between sessions to mitigate carry-over effects. For both the M1 and left DLPFC stimulations, as well as the sham stimulation, a 0.9% normal saline-soaked sponge electrode with a diameter of 6 cm was used to deliver the current. The vmPFC stimulation utilized a 2.5 cm square anodal electrode. All the reference electrodes comprised saline-soaked sponges with a diameter of 6 cm.

This figure illustrates the electrode placements used in transcranial direct current stimulation with the anodal electrode shown in red and the cathodal electrode shown in blue. d depicts sham stimulation with electrodes in grey, indicating no current flow. a Primary motor cortex stimulation: The anodal electrode is placed over the primary motor cortex, with the cathodal electrode on the right supraorbital region. b Left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex stimulation: The anodal electrode is positioned over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the cathodal electrode is placed on the right supraorbital area. c Ventromedial prefrontal cortex stimulation: Electrodes are arranged with the anodal electrode over the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the cathodal electrode placed on the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. d Sham stimulation: Electrodes are placed in active primary motor cortex stimulation conditions but with no current delivered.

Outcome measures

Baseline characteristics of the participants, including age, sex, disease duration, H&Y stage, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), K-MoCA, new-freezing of gait questionnaire, and freezing subtypes, were collected49. Outcome measures were assessed immediately before and after the stimulation. Both the evaluators and the participants were blinded to the specific stimulation conditions to prevent bias in the assessment of the outcomes. This blinding was maintained throughout the study in order to ensure the integrity of the data, as well as the validity of the study results. The TUG test was evaluated under single-task and cognitive and physical dual-task conditions. Additionally, the Stroop, trail-making, and Digit Span tests were administered to evaluate cognitive function. For safety assessment, vital signs were monitored before and after stimulation.

In the single-task TUG test, participants were required to stand from a chair, walk 3 m to a traffic cone at a comfortable pace, walk back to the chair, and sit down. In the cognitive dual-task TUG test, participants performed the test while subtracting three from a randomly selected number ranging from 50 and 100. For the physical dual-task, participants carried a cup filled with water in their preferred hand31. The average completion time of the two trials for each condition were applied in the analysis. The single cognitive task involved seated serial subtraction by threes for 1 min. Dual-task interference during the TUG test was evaluated using both cognitive and motor DTEs (1).

Cognitive DTE was calculated based on the average time taken for each correct response in a serial subtraction task50. The motor DTE was calculated based on TUG completion time. In this study, test-retest reliability of the TUG was assessed using intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) across four visits conducted at one-week intervals. The ICCs were 0.960 for single-task TUG, 0.929 for cognitive dual-task TUG, and 0.921 for physical dual-task TUG, indicating excellent reliability (p < 0.001 for all).

The Stroop, trail-making, and digit span tests were applied to assess cognitive function. The Stroop test assesses cognitive function, including attention, executive function, processing speed, and cognitive flexibility, by measuring an individual’s capacity to suppress automatic responses51. This test consists of three sections: word, color, and color-word pages, each containing 100 items arranged in five columns of 20. Participants were required to read the words or name the colors of the items as quickly and accurately as possible within a 45-second timeframe. The TMT is a neuropsychological tool used to evaluate the psychomotor speed, attention, sequencing, mental flexibility, as well as visual scanning abilities52. For Trail A, participants connected a line as quickly as possible from 1 to 25, with the numbers placed randomly within a 360-second time limit. The test was terminated if a participant made five errors. The Korean version of Trail B requires participants to alternately connect consecutive numbers and Korean letters within a 300-s time limit, also stopping after five errors. The digit span test, both forward and backward, measures immediate recall and attention. This study utilized raw scores from these tests.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations. A GEE was applied to assess the time-by-group interactions across different stimulation targets. The Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to evaluate the normality of the collected data. As most variables did not satisfy the normality assumption, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate changes before and after stimulation. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Responses