Composite vortex air laser

Introduction

With advanced optical tailoring technologies, structured light with finely engineered amplitude, phase, and polarization patterns can be constructed1,2. A distinct form of structured light is optical vortex (OV)3 which is generally produced by tailoring light with designed orbital angular momentum (OAM)4. OVs have distinctive helical phase structures and characteristic doughnut-shaped intensity profiles, which demonstrate the potential for a diverse of applications such as optical manipulation5, quantum communication6, and soft X-ray generation7.

Air laser refers to a cavity-free lasing emission through establishing the optical gain of atmospheric components such as molecular N2+ and N2 at a standoff distance by high-power ultrafast laser pulses8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Recently, it was demonstrated that vortex N2+ lasing emission on the B2Σu+ − X2Σg+ transition at 391 nm can be realized by either pumping a nitrogen gas by a strong 800-nm vortex laser15,16 or seeding a Gaussian laser-pumped N2+ gain media by a weak 400-nm vortex laser17. However, because of the sophisticated strong-field dynamical processes involved in the formation of N2+ laser9,10,11,12,13, several controversial scenarios for interpreting how the OAM information is transferred from the pump or seed optical field to the N2+ lasing emission were proposed15,16,17. On the one hand, with the 800 nm vortex laser pumping, a twofold topological charge of N2+ laser than the pump vortex was observed, which was attributed to the absorption of two more photons for populating the B2Σu+ state than the X2Σg+ state of N2+ during the photo-ionization process of N215. Alternatively, a contradictory experimental result, in which the measured topological charge of N2+ lasing was the same as that of the pump vortex, was observed and interpreted as a result of the pump-to-signal OAM transfer16. On the other hand, with the vortex laser seeding, there also exist contradictory results, where either a Gaussian N2+ laser15 or a vortex N2+ laser with the same topological charge as that of the seed laser17 were observed. Therefore, the consensus on the generation mechanisms of vortex N2+ laser has not yet been reached.

Here, we show the generation of a composite vortex N2+ laser by using a near-infrared Gaussian pump pulse and a weak external Laguerre-Gaussian (LG) seed pulse having a topological charge of ℓ = |2|. By manipulating the relative position, polarization and intensity ratio of the external seed pulse with respect to the pump pulse, the topological charge of the composite vortex air laser can be transformed from ℓ = |2| to |1| or vice versa. The analyses of the beam profiles and the stripe patterns show that the OAM of the N2+ laser is strongly dependent on the intensity ratio and the separation distance between the pump and the external seed pulses. Numerical simulations reveal the essential role of the interference between the pump laser-induced self-seeded and the external-seeded N2+ lasing actions in the change of the topological charge of the N2+ laser.

Results

Basic scheme for generating composite vortex air laser

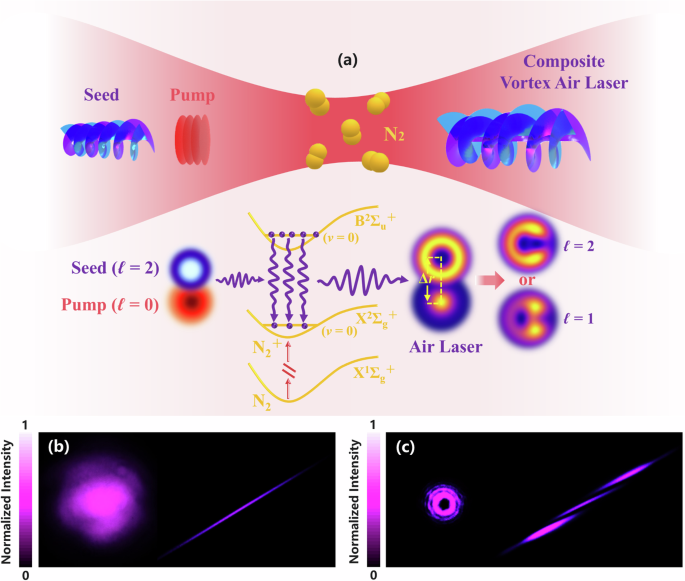

As schematically shown in Fig. 1a, an intense near-infrared pump pulse in Gaussian mode is employed not only to ionize nitrogen molecules and establish the optical gain of N2+ on the B2Σu+ (ʋ = 0)- X2Σg+ (ʋ = 0) transition at around 391 nm, but also to induce a Gaussian (ℓ = 0) second harmonic or white light10 at around 391 nm to serve as a self Gaussian-shaped seed. Moreover, an LG-mode (ℓ = 2) laser pulse at around 391 nm with an adjustable separation distance Δr with respect to the pump pulse is used as the external vortex seed (see Methods). As a result, the generated N2+ laser emissions by the Gaussian-shaped self-seed and the external vortex seed naturally interfere to form a composite vortex air laser at a standoff distance with variable topological charge. Figure 1b, c shows the transverse intensity and dark stripe profiles of (b) the self-seed generated 391 nm N2+ laser and (c) the external seed laser with the designed topological charges of ℓ = 0 and ℓ = 2, respectively.

a Schematic of simultaneously injecting a Gaussian pump and a vortex external seed into a nitrogen gas to generate the composite vortex N2+ air laser, and the corresponding energy-level diagram of N2 and N2+ for illustrating the ionization, the lasing emissions on the B2Σu+ (ʋ = 0) to X2Σg+ (ʋ = 0) transition and the subsequent interference between the self-seeded Gaussian-shaped and the externally seeded vortex-shaped lasers for generating a vortex 391-nm N2+ lasing with ℓ = 2 or ℓ = 1 under different separation distances Δr. Transverse and dark-stripe profiles of (b) the self-seeded N2+ laser and those of (c) the external seed.

Position-dependent modulation of the composite vortex air laser

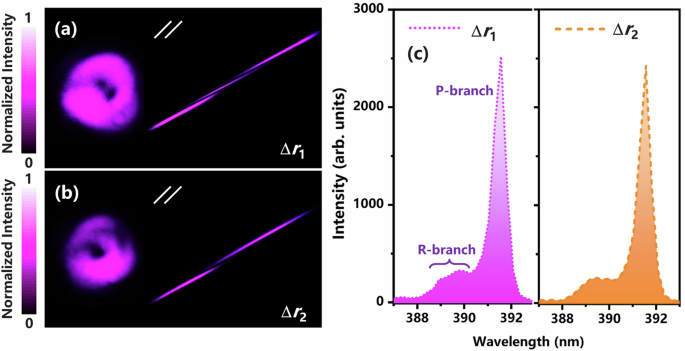

We first examine the effect of the spatial separation distance Δr on the topological charge of the generated 391 nm N2+ air laser. In this measurement, the polarization directions between the pump and external seed pulses are parallel. Figure 2a shows the measured transverse and dark-stripe profiles of the air laser pulse with a separation distance at Δr = Δr1. Note that the lasing signal is optimized in this case, and thereafter refer this overlapping condition as Δr = Δr1 ≈ 0 µm. It can be seen that the transverse energy distribution profile in Fig. 2a shows two vague dark cores. Since the number of dark cores corresponds to the number of phase singularities, the recorded transverse intensity distribution profile in Fig. 2a may indicate that the N2+ laser pulse has a topological charge of ℓ = 2. This consequence is further verified from the corresponding dark stripe profile which also shows an averaged topological charge of ℓ = 2. Then, we slightly modified the separation distance from Δr1 ≈ 0 to Δr2 ≈ 20 µm, and measured the transverse and dark-stripe profiles of the 391-nm laser pulse, as shown in Fig. 2b. However, the recorded transverse intensity distribution and dark-strip profiles in Fig. 2b show that the topological charge of the N2+ lasing emission is changed to ℓ = 1. Moreover, it can be seen in Fig. 2c that the lasing signal intensity obtained at Δr = Δr2 is comparable with that at Δr = Δr1, showing the essential role of the separation distance Δr in the topological charge transformation of the N2+ air laser.

The transverse and dark-stripe profiles of the vortex N2+ laser pulse measured for the separation distance Δr at a Δr1 and b Δr2, respectively. c The corresponding spectrum of the vortex N2+ laser for the conditions of Δr1 (purple dotted line) and Δr2 (orange dashed line), respectively.

A cross-validation experiment was then conducted by setting the topological charge of the external seed at ℓ = −2 (supplementary Fig. S1 and Note 1) with a spiral phase plate (SPP). The same position-dependent modulations of the composite vortex air laser were observed from the transverse beam and dark-stripe profiles (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Note 1), in which the dark stripes exhibit an opposite orientation to those shown in Fig. 2. These results indicate that the topological charge of the 391-nm N2+ air lasing emission is not always the same as that of the external laser pulse at ℓ = 2, showing its composite vortex nature.

Polarization-dependent modulation of the composite vortex air laser

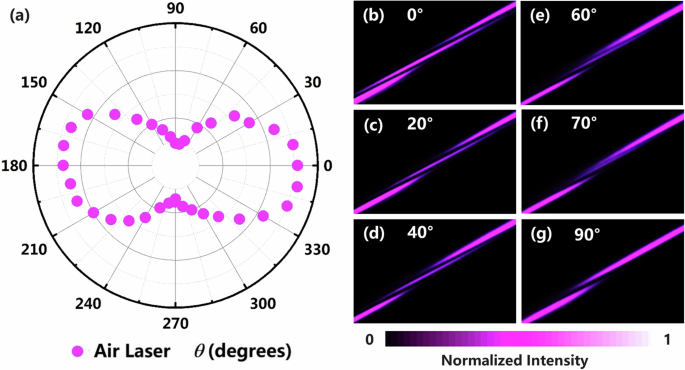

We then investigate the effect of the laser polarization states on the topological charge of the N2+ air laser by fixing the separation distance at Δr = Δr1 ≈ 0. In Fig. 3a, we show the recorded lasing intensities by varying the relative polarization direction of the external seed pulse with respect to the pump pulse, in which θ = 0° and 180° represents that the polarization directions of the pump and seed pulses are parallel, while θ = 90° and 270° denote that the polarization directions of these two pulses are perpendicular. When θ increases, the intensities of the vortex N2+ laser change periodically with the maximum occurring under the parallel condition and the minimum under the perpendicular condition. This variation trend agrees with the Gaussian-shaped air laser generation18,19. However, the topological charge of the vortex N2+ laser gradually changes from ℓ = 2 to ℓ = 1 when the polarization direction of the pump pulse with respect to the external seed pulse varies from parallel to perpendicular, as can be seen from the dark-strip profiles shown in Fig. 3b–g. It should be pointed out that the transformation of the topological charge occurs mainly when θ is larger than 60° (for details, see Supplementary Fig. S3 and Note 2), where the laser intensity sharply decreases (see Fig. 3a).

a The composite vortex air laser intensity is measured as a function of θ, which is the angle between the electric field direction of the pump laser pulse and that of the external seed pulse. b–g the dark stripe profiles measured at different angles of θ = b 0°, c 20°, d 40°, e 60°, f 70° and g 90°, respectively.

Intensity-dependent modulation of the composite vortex air laser

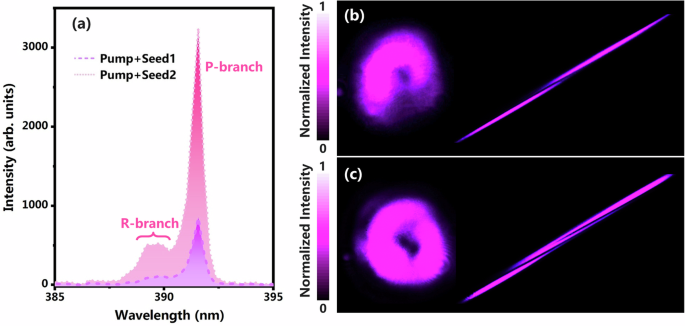

We also study the effect of the external-seed laser intensity on the topological charge of the composite air laser. Figure 4a presents the spectra of the N2+ air laser pulse generated by the external seed pulse respectively with the energies of 7 pJ (seed 1: purple dashed line) and 240 pJ (seed 2: pink dotted line). Clearly, the air laser intensity induced by the weak seed pulse is much lower than that by the higher-intensity seed pulse. Figure 4b, c shows the corresponding transverse beam and dark stripe profiles of the vortex N2+ air laser obtained respectively with the (b) weak and (c) strong seed pulses. Besides, it is evident that the topological charge of the vortex N2+ laser pulse changes from ℓ = 1 to ℓ = 2 when the external-seed laser intensity becomes stronger. This topological charge transformation is also verified by the cross-validation experiments by setting the topological charge of the external seed pulse to ℓ = −2, which demonstrate the transformation from ℓ = −1 to ℓ = −2 under the same seed intensity conditions (see Supplementary Fig. S4 and Note 3).

a Spectra for the vortex N2+ laser induced by the external seed pulse with the laser energies of 7 pJ (seed1: purple dashed line) and 240 pJ (seed 2: pink dotted line). The corresponding transverse and dark-stripe profiles of the vortex N2+ laser pulse measured for b the weak and c and strong seed laser pulses, respectively.

Numeric simulation of composite vortex air laser

To interpret the observed topological charge modulation of the vortex N2+ laser, we consider the possibility that under the Gaussian pump and the vortex seed conditions the N2+ air laser may be generated through the two seeding channels: (i) the self-generated Gaussian-shaped seed through nonlinear frequency conversion of the pump laser pulse8, and (ii) the externally-injected vortex seed. We therefore conducted numerical simulations on the basis of the composite vortex N2+ laser having two components, i.e., a Gaussian component ({{rm{alpha }}}{E}_{ell 1}({r}_{1},{phi }_{1},{z}_{1})) generated through Channel (i) with ℓ1 = 0 and a vortex component ({{rm{beta }}}{E}_{ell 2}({r}_{2},{phi }_{2},{z}_{2})) generated through Channel (ii) with ℓ2 = 2, where r, ϕ and z represent the cylindrical coordinates, α and β are the amplitude constants (see “Numerical simulation in Methods”). In the simulation, we assume that the two components have the same temporal profiles20, and are temporally overlapped. The polarization directions of the two components are set to be parallel to each other. After the generation of the composite vortex N2+ laser, an interference between the two components takes place. Based on this interference model, the simulated transverse intensity profiles (left) and the phase distributions (right) of the N2+ air laser under different intensity ratio (gamma ={|alpha {E}_{ell 1}/beta {E}_{ell 2}|}^{2}) and separation distance Δr = r2 − r1 conditions are obtained, as shown in Fig. 5. We first show the simulated intensity (left) and phase (right) distributions of the N2+ laser pulse with (a) γ = 0 (i.e., without the Gaussian self-generated seed injection, and Δr = 0) and (b) 1/γ = 0 (i.e., without the external seed injection, and Δr = 0), respectively. Clearly, in Fig. 5a, the N2+ laser shows a Laguerre-Gaussian (LG) mode with a discernible dark core at the center in the intensity distribution, and two overlapped singularities in the phase plane, i.e., ℓ = 2, in which a positive charge denotes a counter-clockwise increase in the phase21. While in Fig. 5b, the N2+ laser shows a Gaussian intensity distribution with ℓ = 0 (left), and there is no discernible phase singularity observable in the phase plane (right). This indicates that in the absence of the interference between the two N2+ laser components, the N2+ laser pulse will have a topological charge same as either the self-seed pulse or the external seed pulse.

The transverse intensity profiles (left) and the phase distributions (right) of the N2+ air laser obtained under the conditions of a γ = 0, b 1/γ = 0, c Δr = 20 µm, γ = 0.1, d Δr = 20 µm, γ = 0.2, e Δr = 20 µm, γ = 0.5, f γ = 0.4, Δr = 0 µm, g γ = 0.4, Δr = 15 µm, and h γ = 0.4, Δr = 20 µm, respectively.

We then simulate, as shown in Fig. 5c–e, the transverse intensity (left) and phase (right) distributions of the vortex N2+ laser with γ = (c) 0.1, (d) 0.2 and (e) 0.5, respectively, but with Δr being kept at a constant value of Δr = 20 µm. Here the waist radius of the two N2+ laser components was set to be constant at ~25 µm. When γ = 0.1, the vortex air laser exhibits two dark holes in the transverse intensity profile and two-phase singularities in the phase pattern (Fig. 5c), resulting in the topological charge of ℓ = 2, which indicates that the air laser component resulting from the external seed dominates. When γ is increased to γ = 0.2, one hole in the transverse intensity profile becomes smaller, and the distance between the separated singularities enlarges, as can be seen in Fig. 5d. Moreover, when γ is further increased to γ = 0.5, as shown in Fig. 5e, there is one hole left in the transverse intensity profile, and one singularity vanishes from the phase pattern, resulting in the transformation of topological charge from ℓ = 2 to ℓ = 1. This result indicates that the relative intensity ratio γ of the two laser components plays a key role in determining the topological charge number of the composite vortex N2+ air laser when Δr ≠ 0.

Next, we simulate, as shown in Fig. 5f–h, the transverse intensity (left) and phase (right) distributions of the vortex N2+ laser with Δr = (f) 0 µm, (g) 15 µm and (h) 20 µm, respectively, but with γ being kept at a constant value of γ = 0.4. Obviously, when Δr = 0 µm, there are two distinct dark holes in the transverse intensity profile and two phase singularities in the phase pattern in Fig. 5f, which indicates the vortex N2+ laser has a topological charge of ℓ = 2. When the separation distance is increased to Δr = 15 µm, one dark hole in the transverse intensity profile gets smaller and the distance between the separated singularities in the phase pattern becomes farer, as shown in Fig. 5g. When the separation distance is further increased to Δr = 20 µm (Fig. 5h), one hole disappears in the transverse intensity profile, and there is only one singularity in the phase pattern. This means that the transformation of the topological charge from ℓ = 2 to ℓ = 1 takes place, indicating that Δr is a key parameter in controlling the topological charge of the composite vortex N2+ air laser. Furthermore, based on the interference model, our simulations also show that a vortex air laser with a desired higher-order topological charge can be generated by designing the OAMs of the two components of a composite vortex air laser under different interference conditions (see supplementary Fig. S5 and Note 4).

Discussion

Based on the simulation results shown in Fig. 5c–e, we can interpret the mechanism for the topological charge modulations of vortex N2+ laser shown in Figs. 3 and 4. As the polarization directions between the pump and the external seed pulses change from parallel to perpendicular, the intensity of the composite vortex air laser decreases significantly (Fig. 3), which was ascribed to the variation of the azimuthal quantum number M of N2+ related to the polarization direction of the seed pulse in the two cases18,19,22, as well as the alignment of N2+ induced through the preferential ionization of N2 by the pump pulse19. That is, the intensity decrease shown in Fig. 3 mainly originates from the air laser component induced by the external seed pulse. Therefore, the intensity of the air laser component resulting from the self-generated seed will remain constant when the polarization directions between the pump and the external seed pulses from parallel to perpendicular. This leads to the increase in the intensity ratio γ, and thus the transformation of the topological charge from ℓ = 2 to ℓ = 1, as shown in Fig. 3. It should be pointed out that in the simulation the interference will not occur at θ = 90° and θ = 270°, i.e., when the polarization directions of the two components of the composite air laser are perpendicular. The experimentally observed interference occurring at θ = 90° and θ = 270° may result from the birefringence effect in the plasma filament23, and also from the fact that it is hard to make the external seed strictly perpendicular to the pump light in real experiments settings (see Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7, and Note 5). On the other hand, as the intensity of the external seed pulse increases, the intensity of the air laser component resulting from the self-generated seed will also remain constant, and thus the enhancement of the composite vortex air laser intensity in Fig. 4 is mainly from the component induced by the external seed. This leads to the decrease in γ, and finally the change of the topological charge from ℓ = 1 to ℓ = 2.

Judging from the simulation results in Fig. 5f–h, the separation distance Δr is another crucial parameter modulating the topological charge of the composite vortex air laser, a finding supported by the experimental results in Fig. 2. In the experiments, the phase singularities can be manipulated from 2 to 1 and vice versa by carefully controlling the separation distance Δr between the pump and the seed, while leaving the laser intensity invariant. Since the propagating direction of the externally seeded N2+ laser follows that of the external seed, the movement of the external seed will introduce the separation distance between the N2+ lasers seeded respectively by the external seed and the self-generated seed. However, it should be pointed out that, if the separation distance Δr is further increased and exceeds a certain value, a so-called non-uniform amplification mechanism17 may also make a contribution to the change in the topological charge of the composite vortex air laser, resulting in an output of ℓ = 0 (see Supplementary Figs. S8 and S9, and Note 6). These results confirm that it is feasible to achieve a tunable topological charge of ℓ = 0, 1, 2 by manipulating the separation distance Δr.

As a consequence, the simulation and experimental results show the essential role of the interference between the two components originating from the self-generated seed and the externally injected seed in the generation of vortex air lasers, which strongly depends on their relative intensities and positions. It should be noted that in the generation of vortex N2+ laser, the component induced by self-generated seed would always exist more or less depending on the pump laser intensity. We thus speculate that the previously observed contradictory topological charge results of the vortex air laser15,16,17 may originate from their different interference effects between the N2+ laser components generated respectively by the self-generated and externally injected seed pulses.

To summarize, we have demonstrated the experimental realization of generating composite vortex N2+ air lasers by employing a Gaussian pump and LG-seed pulses. We have found that the topological charge of the vortex N2+ air laser can be transformed from ℓ = |2| to |1| or vice versa by manipulating the relative positions, polarization, and intensity ratio between the external seed pulse and the pump pulse. We have performed the numerical simulations and revealed that the transformation of the topological charge of the vortex N2+ air laser can be ascribed to the interference between the two N2+ laser components induced respectively by the pump-laser-induced self-generated seed and the externally injected seed, which depends strongly on their intensity ratio γ and separation distance Δr. This interference mechanism over controlling the topological charge of the vortex N2+ air laser, where the spatial phase of the seed is maintained in the air laser during the propagation and amplification17,24, is fundamentally different from those based on the transfer of the OAM information from the pump15,16 to the N2+ gain medium, and then to the N2+ lasing emissions. Our results not only provide a way to generate composite vortex air lasers with higher degree of OAMs by introducing higher topological charge into the external seed and the pump pulses, but also open up avenues for remote quantum manipulation of structured light through strong-field laser ionization of a variety of molecules.

Methods

Experimental details

The experiment was conducted using a Ti: sapphire laser system (Spectra Physics, Spitfire ACE) that produced a linearly polarized 800-nm, 40-fs pulse train in the Gaussian mode (ℓ = 0) with a repetition rate of 200 Hz. The pulse beam was split into a strong and a weak arm. The strong arm (3.4 mJ) served as the pump and was focused by a 30-cm fused silica lens into a gas chamber filled with pure nitrogen gas at 25 mbar. The weak arm was first transformed into the LG mode (ℓ = 1) via the SPP, and then frequency-doubled in a 0.3-mm-thick β-barium-borate crystal to generate an LG-mode external seed (ℓ = 2) at around 391 nm with the maximum energy of 250 pJ. Unless otherwise specified, we fixed the energy of the external seed pulse at 100 pJ. The external seed was also focused into the chamber to induce the N2+ laser by another 30-cm fused silica lens, which was placed on a three-dimensional stage, so that the separation distance Δr between the external seed and self-generated seed (i.e., pump) pulses at the focal spots can be modified. Note that the topological charge of the external seed can be changed from ℓ = 2 to ℓ = −2 by flipping the SPP. The external seed energy was controlled by a half-wave plate and a polarizer, and the time delay of the external seed pulse with respect to the pump pulse was fixed at t = 300 fs (for details, see Supplementary Fig. S10 and Note 7), with which the interference between the self-seed and the external seed that occurs at t = 0 can be eliminated. The polarization direction of the pump pulse with respect to the external seed pulse was controlled by a half-wave plate inserted in the external seed path. The forwardly generated 391 nm lasing emission was collimated by a 25-cm fused silica lens and then filtered out from the pump light by a band-pass filter. The beam first passed through a 50%:50% beam splitter and then was probed respectively by a fiber spectrometer (HR 4000, Ocean Optics) for spectral analysis and a CMOS camera for beam pattern analysis. In the latter case, the beam was focused onto the CMOS camera by either a 10-cm fused silica lens to examine the transverse profile of the beam or a cylindrical lens (f = 1 m) to extract the topological charge from the dark stripe profile25,26.

Numerical simulation

For a single-ringed LG beam with a topological charge ℓ, its amplitude is given by ref. 27,

where r, ϕ and z represent the cylindrical coordinates, w is the beam radius, k is the wave vector, φ is the initial phase value. Since the wavefront of the femtosecond laser emitted by the laser system has a large radius of curvature, we neglect the curvature of the N2+ laser. Therefore, the total amplitude of the dual-channel generated composite vortex N2+ laser carrying the topological charges ℓ1 = 0 and ℓ2 = 2 with a separation distance Δr = r2 − r1 can be expressed as,

where α, β are the amplitude constants. In this case, the intensity ratio between these two components is defined as (gamma ={|{{rm{alpha }}}{E}_{ell 1}/{{rm{beta }}}{E}_{ell 2}|}^{2}).

Responses