Consumers’ perspectives on antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals: a systematic review

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance has become one of the biggest threats to global human health1,2. More and more existing antibiotics become ineffective against resistant bacteria2. About 1.27 million people died from antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections in 20193. Without intervention, the figure could rise to 10 million deaths each year by 20504. Although the development of antibiotic resistance is a natural phenomenon, it is largely accelerating by inappropriate antibiotic use in both humans and food animals2. Globally, 72.5% of antibiotics are used in animals5. It was estimated that 131,109 tons of antibiotics were used in food animals in 2013 and will reach to 200,235 tons by 20306.

Antibiotics are usually administered to food animals for two purposes: therapeutic use and subtherapeutic use. For therapeutic use, antibiotics are normally applied to treat animals with clinically diagnosed infectious diseases7,8. For subtherapeutic use, low doses of antibiotics are usually added to feed or water to prevent healthy animals from getting sick (prophylaxis) or to promote growth9,10,11. While therapeutic use of antibiotics is essential for maintaining animal health, antibiotics are widely used in animals for the purpose of subtherapeutic function—an inappropriate use12,13,14. Hence, inappropriate antibiotic use in food animals is considered an important contributor to the increasing antibiotic resistance6,15,16. Furthermore, antibiotic-resistant bacteria in food animals caused by the inappropriate use can be transmitted to humans7. The transmission can happen through direct or indirect contacts between humans and animals, including direct animal contact, through the food chain, and via environmental routes17. Given that most antibiotic classes which are clinically important to humans are currently used in food animals, such transmission imposes significant risks to human health5.

In recent years, several countries have taken some measures to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use in food animals. For example, using antibiotics to promote growth has been banned in the EU since 200618 and in China since 202019, and has been limited to antibiotics which are not clinically important to humans in the US since 201720. However, it is still common to have antibiotics added to feed or water to prevent diseases, or promote growth in agriculture and aquaculture, particularly in the developing countries2,11,21,22,23.

To address the health threats posed by antibiotic resistance, reducing inappropriate antibiotic use in food animals is a vital step6,17,24,25. Given that it is the consumers who eventually purchase and consume the food products, they can play a critical role in reducing inappropriate antibiotic use in food animals. Research has shown that consumers’ attitudes towards and perceptions of food products have a huge impact on their consuming intentions, behaviours, and demands26,27. The more consumers perceive a product as risky, the more they are unwilling to take on the risk and choose not to consume the product28,29. Consumers’ demands and preferences can also influence industry strategies as well as government policies and regulations30. Therefore, it is important to understand consumers’ perspectives (i.e., knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes) on antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals. While research so far has shed light on those aspects31,32,33,34,35,36,37, the measures and findings were varied and, sometimes, conflicting. What is missing is a comprehensive and coherent understanding of this subject. Recently, Barrett and colleagues conducted a scoping review on consumers’ concern about antibiotics in meat products in the US, Canada, and the EU38. The review was, however, focused on whether consumers were concerned about antibiotics in meat products and the reasons for concern (i.e., human health and animal welfare), which shed limited light on consumer’s knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes regarding antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals. Therefore, the present research aimed to synthesize all published literature to draw a comprehensive understanding of consumers’ perspectives on antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals.

Results

Descriptive statistics of included studies

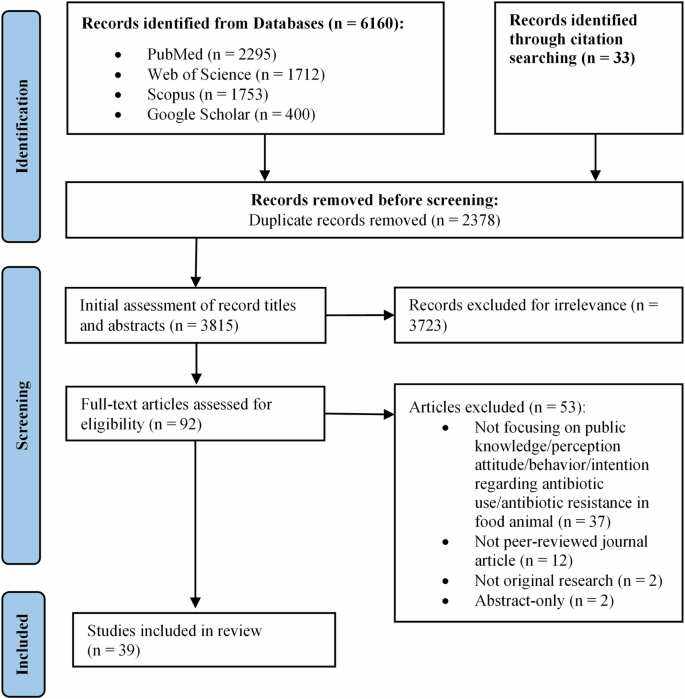

The literature searches identified 3815 records in total (Fig. 1). Among them, 39 articles were included in the review. The detailed characteristics of each included article are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection procedure.

Publication year

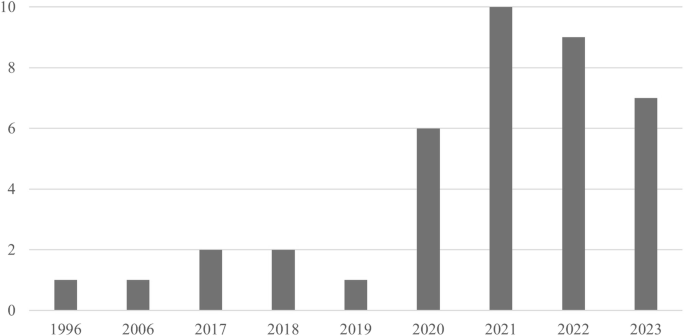

Most included studies (n = 32, 82.1%) were published from 2020 to 2023, 12.8% (n = 5) were published between 2015 and 2019, and only 5.1% (n = 2) were published before 2015 (Fig. 2).

The publication year of included studies.

Research locale

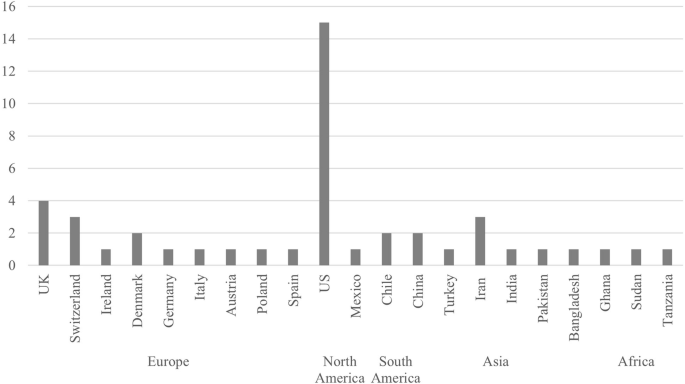

A total of 21 countries from 5 continents were involved in the 39 included studies (Fig. 3). The US had the most studies (n = 15), followed by the UK (n = 4), Switzerland (n = 3), and Iran (n = 3). In addition, 2 studies were conducted in multiple countries, with one of them collecting data from Germany, Italy, and the US34 and the other from five European countries (Austria, the UK, Poland, Denmark, and Spain)39.

The total number of study locales was greater than 39 because two studies were undertaken in multiple locales.

Study design

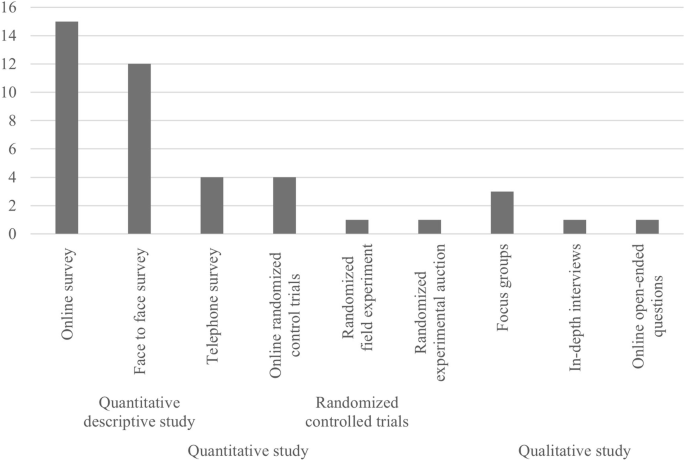

Figure 4 presents the study design and data collection method of included studies. Overall, 34 studies (87.2%) applied a quantitative approach and 5 applied a qualitative approach (12.8%). Notably, three quantitative studies utilized two data collection methods40,41,42. The most used quantitative study design was quantitative descriptive study (n = 31, 79.5%) collecting data via online survey (n = 15), face-to-face survey (n = 12), or telephone survey (n = 4). Besides, 6 studies (15.4%) applied quantitative randomized controlled trials, with four of them conducted online, one field experiment, and one experimental auction. As for the qualitative studies, 3 out of 5 collected data through focus groups, while the fourth one used in-depth interviews and the last one utilized online open-ended questions. Furthermore, only 6 studies were based on established theoretical frameworks (15.4%).

The total number of data collection methods was greater than 39 because three studies used two data collection methods.

Sample characteristic

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics of included studies. Approximately two thirds of the studies targeted either the public/consumers or consumers of certain animal-derived food products (i.e., meat, dairy, pork, and poultry). The remainders targeted food preparers/grocery shoppers, household heads, or college students. Nearly two thirds of the studies focused on certain food products or animals, including general meat, pork/pig, beef/cow, poultry/chicken, eggs, dairy products (i.e., cheese and milk), and raw food. Notably, 1 study examined three food products (i.e., pork, eggs, and milk)43.

The studies covered 31161 participants. The participants of two studies32,35 were excluded as they were the same sample set as another two studies31,44, respectively. Participants covered different ages and genders (Table 1). The sample size of qualitative studies ranged from 14 to 779. The sample size of quantitative studies ranged from 80 to 5693, with most of them (58.8%) having a sample size >500. Over one third of studies (n = 14, 35.9%) did not report sampling technique. Among the studies who reported sampling technique, the most used ones were random (25.6%) and quota (20.5%) sampling. Notably, only 6 studies (15.4%) reported response rate, which varied from 17% to 74%.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of included studies is presented in Supplementary Table 2–4. All 39 included articles passed the first two screening questions (i.e., “Are there clear research questions?” “Do the collected data allow to address the research questions?”). The studies were further appraised based on the study design, with 29 studies falling into the category of quantitative descriptive studies, 6 quantitative randomized controlled trials, and 5 qualitative studies. Notably, 1 article consisted of two substudies, with one of them falling into quantitative descriptive study and another one randomized controlled trial42. The most common reason for an unclear risk of bias was due to a lack of reporting on response rate (79.3%) among quantitative descriptive studies.

Identified themes

Our review identified seven themes regarding consumers’ perspectives on antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals. The key findings of each theme are presented in Table 2.

The use of antibiotics in food animals

General use of antibiotics in food animals

Out of the 39 studies, 21 provided results regarding consumers’ perspectives on antibiotic use in food animals in general without specifying the purpose of usage (i.e., therapeutic or subtherapeutic). Therefore, the findings can be conflicting and confusing. While a study conducted in the US revealed that participants had no or little knowledge about antibiotic use in food animals44, studies undertaken in Pakistan45, Sudan46, and the US47 suggested that most consumers believed that antibiotics are widely used in food animals. Focus group discussions conducted in Ireland revealed mixed views on the motivations of antibiotic use in farming48. Some participants believed that antibiotics are used for the best interest of animals, while others thought that antibiotic use is driven by profit and thus leading to antibiotic overuse48. A study conducted across Germany, Italy, and the US also revealed that participants in these three countries were all sceptical about the justification of antibiotic use in livestock, with German participants holding the strongest opinion, followed by Italians and Americans34. However, studies undertaken in Bangladesh49 and the UK31,32 found consumers had a moderately49 or slightly31,32 favourable attitude towards the general use of antibiotics in food animals.

Fifteen studies investigated consumers’ perceived benefits and risks of antibiotic use in food animals. With respect to the benefits, consumers agreed antibiotic use in food animals can improve animals’ health, reduce pain for sick animals, help to manage infectious diseases, and maintain food safety34,35,44,48,50,51. As for the risks, consumers believed that antibiotic use in food animals poses threats to human health, hampers animal welfare, leads to antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the environment, and results in less effective antibiotic treatments in both animals and humans31,32,34,35,37,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,52,53. Although these studies did not specify the purpose of usage (i.e., therapeutic or subtherapeutic), consumers seemed to recognize the benefits of therapeutic use and the potential risks of inappropriate use and overuse. However, there were some differences among consumers from different countries. For example, a cross-country comparison revealed that participants in Germany, Italy, and the US all regarded antibiotic use in food animals as a health threat to humans, but only US participants recognized the benefits of antibiotic use in food animals34. Meanwhile, a 5-country comparison study revealed that Spanish participants were least concerned about the risks of antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals, the Danish and Polish participants were mildly concerned, the UK participants were more concerned, while the Austrian participants were most concerned and most critical39. Moreover, consumers were less concerned about the health risks posed by antibiotic use in food animals when compared to other food safety issues (e.g., genetically modified foods, food additives, and hormones)41,54,55,56,57.

Three studies provided information on consumers’ attitudes towards reducing58 or removing antibiotics from livestock industries34,48. Both the advantages and disadvantages of restricting antibiotic use in food animals were discussed. The advantages included reducing the risk of antibiotic residues presenting in animal-derived food products and the transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, improving animal welfare, and leading to more natural animal-derived food productions34,58. The disadvantages included leading to sick animals entering the food chain thus affecting human health, resulting in animal suffering, increasing the prices of animal-derived food products, and positing challenges to farmers (e.g., the monetary and time investment on making changes to their infrastructure and loss of animals because of illness)34,48,58. Noticeably, though there was some concern about the adverse effect of restricting antibiotic use in food animals on animal health and farmers’ financial loss, consumers were mostly concerned about food safety and human health48. In general, consumers were in favour of reducing antibiotic use in food animals58, but disagreed on a total ban of antibiotic usage48. Instead, consumers called for more protective measures to reduce the need for antibiotic usage, including vaccination, good husbandry, good hygiene management, low stocking density, isolating sick animals, and regular veterinarian visits39,48.

Therapeutic use of antibiotics in food animals

Two studies conducted in Chile40 and the US59 examined consumers’ opinions on therapeutic use of antibiotics. Although most participants supported the use of antibiotics to treat sick animals, they did not want these animals to enter the food chain after receiving the treatment40,59. Further, consumers’ support for therapeutic use was associated with the chance of animal recovery and exposure to information on the adverse effect of usage. Support increased as the probability of sick animals recovering after treatment increased40 and decreased after exposure to information on the link between antibiotic use in food animals and increasing antibiotic resistance59. Some US participants considered the adverse effects of both treating (i.e., increasing antibiotic resistance and polluting the environment) or not treating (i.e., leading to animal suffering and farmers facing financial loss) the sick animals with antibiotics, and acknowledged that there is a trade-off for either option59. US participants also highlighted that farmers should isolate sick animals, use antibiotics prudently with the supervision of a veterinarian, observe a lengthy withdrawal period, and segregate the manure when using antibiotics to treat sick animals59. The participants further emphasized the importance of improving management practices (i.e., avoiding overcrowding and providing appropriate diets) and seeking alternatives to reduce the need for antibiotics59. The favourable attitude towards therapeutic use of antibiotics among consumers was also found in several other studies conducted in the US33,35,44 and Europe39,51. These consumers thought it is acceptable to use antibiotics to treat diseases and tended not to worry about it35,39,44. They also agreed that using antibiotics to treat diseases improves animal welfare and delivers more benefit than harm35,44,51.

Five studies provided findings regarding consumers’ knowledge about using antibiotics to treat diseases. Studies undertaken in China52 and Chile50 suggested that most consumers knew that antibiotics can treat infections in food animals. A study conducted in Tanzania found most participants believed that antibiotics are widely used to treat infectious diseases in food animals60. Only two studies specifically mentioned bacterial and viral infections, showing 49% of US participants knew antibiotics can treat bacterial infections in food animals, but only 31% of them correctly identified that antibiotics cannot treat viral infections35,44. Only 28.6% of participants in China knew that antibiotics used for animals are the same as those used for humans52. These findings suggested that although consumers were in favour of therapeutic use of antibiotics in food animals, their knowledge about it was low.

Subtherapeutic use of antibiotics in food animals

Eight reviewed studies provided results related to the use of antibiotics for preventing disease and/or promoting growth. The overall findings indicated that although consumers lacked understanding about subtherapeutic use of antibiotics in food animals, they were unfavourable and concerned about it. Most consumers were not aware that antibiotics can stimulate the growth of animals52 and can be used for preventing diseases in food animals48. Yet, consumers agreed that antibiotics are widely used for disease prevention and growth promotion in livestock industries34,52,53 and such practice contributes to antibiotic resistance52. These results suggested that though consumers lacked awareness of subtherapeutic use, they became very sceptical when researchers brought up the topic, indicating a deep mistrust of antibiotic use practice in livestock industries.

The findings regarding the attitudes towards subtherapeutic use of antibiotics varied across studies. A qualitative study conducted in the US found participants made a clear distinction between therapeutic and subtherapeutic use (i.e., for promoting growth and preventing diseases), and regarded the subtherapeutic use as unacceptable59. Most participants in another US study were very concerned about antibiotic use as growth promoters and considered it unacceptable, while less of them were concerned about and against using antibiotics for disease prevention35. Meanwhile, a study conducted in five European countries (Austria, the UK, Poland, Denmark, and Spain) revealed that most participants were concerned about the impact of preventive antibiotic use on increasing antibiotic resistance and considered it unacceptable39. The divided opinion on preventive use of antibiotics was also found in another qualitative study carried out in Ireland, where some participants regarded the preventive use as a normative, standard, and acceptable practice, while others felt the opposite48. These conflicting results could be due to a lack of knowledge about preventive use and the health risks associated with it.

Noticeably, one US study investigated consumers’ intention to vote for a ban on subtherapeutic use of antibiotics in pork production and their willingness to pay a tax for the ban61. Participants had a strong demand for banning subtherapeutic use and were willing to pay an average of $ 125 tax for the ban. However, the proposed tax level in the study had a significant impact on the intention to vote for the ban, with a higher tax rate leading to a lower possibility of voting61.

Antibiotic residues in animal-derived food products

Only 5 studies mentioned antibiotic residues in animal-derived food products with varied findings. Most participants in an Indian study reported limited knowledge about antibiotic residues in animal-derived food products56. Most participants from Tanzania had heard of antibiotic residues and were aware that animal waste/manure containing antibiotic residues are used in agriculture60. The majority of participants in a Ghanian study had also heard of antibiotic residues and believed that both locally produced and imported meat sometimes contain antibiotic residues62. However, most of them were not aware of the transmission pathways of antibiotic residues from food to humans via consumption62. Most US participants slightly agreed that antibiotic use in food animals pollutes food products and the environment with antibiotics35,44, or antibiotic residues34, while Italians and Germans held stronger opinions34. The majority of participants in China were concerned about consuming food products with antibiotic residues having adverse impacts on human health52.

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria associated with antibiotic use in food animals

Seven out of the 39 studies provided results about antibiotic-resistant bacteria associated with antibiotic use in food animals. Participants in China appeared to believe that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are widespread in farming52, while participants in Ghana thought both locally produced and imported meat sometimes contain antibiotic-resistant bacteria62.

A substantial knowledge gap was apparent regarding the transmission pathways of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from animals to humans45,48,52,55,63. A qualitative study conducted in Ireland found participants did not realize that antibiotic resistance means bacteria, not humans, become resistant to antibiotics48. These participants believed that people become immune or resistant to antibiotics due to taking too many antibiotics48. Similar belief was found in another qualitative study undertaken in Switzerland, where participants believed that only the use of antibiotics with humans results in antibiotic resistance in humans, without realizing that people can get infected from other sources55. Consequently, these participants were confused about the transmission pathways of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from food animals to humans48,55. Participants were surprised by the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria after exposure to information about it48. Some participants still had difficulty in understanding the transmission pathways after information exposure48. These participants regarded consuming antibiotic residues in food as the main way of antibiotic-resistant bacteria transmitting from animals to humans, thus becoming concerned about getting infected from diet48. Participants’ understanding of antibiotic resistance improved when they perceived it as “bad bacteria/germs” becoming stronger48. These participants believed that “good hygiene” can kill “bad bacteria/germs”. Therefore, to mitigate the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, they thought preventive measures and good hygiene practices should be adopted both on farms and by individuals48.

On the other hand, most consumers in China and Switzerland correctly recognized that antibiotic-resistant bacteria in animals can be transmitted to humans when eating undercooked meat (especially poultry meat) and drinking contaminated water52,63. However, these consumers underestimated the risk of handling raw meat, contacting live farm animals, and eating tainted vegetables and fruits52,55,63. Besides, a Swiss study revealed that consumers had some misconceptions about the transmission risks of antibiotic-resistant bacteria: they did not realize that the transmission risk of raw meat is higher than processed meat and of raw chicken is higher than other raw animal-derived food products, and that organic and locally produced meat may also be affected by antibiotic-resistant bacteria55. Noticeably, another Swiss study revealed that watching an educational video on how antibiotic-resistant bacteria transmit from animals to humans significantly increased participants’ knowledge and perceived susceptibility of the transmission risks64.

Regulations on antibiotic use in food animals

Many countries have employed a range of regulations on antibiotic stewardship in food animals. For instance, The EU has banned antibiotic growth promoters in 2006 and banned preventive use of antibiotics in animal feed for groups of animals in 202210,65. The US has banned the use of antibiotics which are medically important to humans for promoting growth in 201710,20. China has banned antibiotic growth promoters in 202019.

Eight studies examined consumers’ knowledge about and perceptions of regulations on antibiotic stewardship in food animals. Consumers in the UK showed a generally higher level of knowledge about EU and national regulations on antibiotic use in food animals, while consumers in the US and China seemed to be less knowledgeable about the national regulations on this issue31,32,33,51,52. There were some common misunderstandings regarding regulations on antibiotic use in food animals across countries, such as the belief that antibiotic growth promoters are still legal31,32,33 and that there are no regulations on antibiotics used in food animals31,32,48,52. Consumers also believed that not enough measures have been taken to restrict the misuse and overuse of antibiotics in food animals52 and that regulatory agencies are inefficient and untrustworthy48,50. Consequently, consumers called for increased appropriate governance and regulatory control to ensure responsible antibiotic use in food animals, as well as incentive measures to support farmers to make proactive changes to reduce antibiotic use45,48.

Information source on antibiotic use in food animals

Five out of the 39 studies investigated the information source regarding antibiotic use in food animals. Common information sources for consumers included traditional media (e.g., newspaper, TV, and radio), social media (e.g., Facebook and YouTube), the internet, health professionals/doctors, family and friends, teachers/schools/universities48,50,52,55,62. Noticeably, information from scientists, health professionals/doctors, and government institutions was perceived as more accurate and trustworthy52. However, compared to other information sources (e.g., social media and the internet), these sources were less available and less commonly used52. Further, a qualitative study conducted in Chile revealed that consumers thought the information available to them is very scarce and that they need more trustworthy, official, and accessible sources of information50.

A study examined US consumers’ information avoidance behaviour by giving participants a choice to (a) watch a video about antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals—information seeking, or (b) watch a video with a black screen and nature white noise—information avoidance44. The authors found that about 40% of participants chose option b. The most common reasons given by those participants for their choice were unwillingness to change their existing view, fear (afraid to know about antibiotic resistance), and feeling powerless (nothing they can do about it). Moreover, participants who had little knowledge about antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals were more prone to avoiding information44. For participants who opted to access antibiotic resistance information, their risk perception of antibiotic resistance significantly increased after watching the video, with the increase being greater for participants with little pre-knowledge44.

Antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use labelled food products

More than half (n = 23, 59.0%) of the included studies provided results on consumers’ perceptions of, attitudes and purchase behaviours towards, or willingness to pay for various antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use labelled food products. Identified examples included “raised without antibiotics” labelled pork32, antibiotic-free labelled food products43,47,50,51,66,67,68,69, QR code (embedded with antibiotic use information) labelled pork31, minimal use of antibiotics labelled pork36, responsible antibiotic use labelled milk42, as well as organic food products33,57.

UK consumers believed that antibiotic-free and QR code labelled food products are safer, healthier, tastier, of higher quality, and more likely free from antibiotics as well as have higher animal welfare standards31,32. US consumers also believed that antibiotic-free labelled meat are healthier than unlabelled meat and that unlabelled meat contain antibiotics or hormones66. Moreover, UK consumers agreed that information provided by the labels are useful, accurate, reliable, trustworthy, and reassuring31. These consumers also believed that buying labelled products will reduce their risks of consuming antibiotic residues and getting infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria31. Though consumers formed positive perceptions of antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use labelled food products, there were some barriers preventing them from purchasing. For instance, consumers in the UK and US reported that they are not familiar with the labelled food products and believed that these products are harder to find and more expensive31,32,47. Furthermore, the social norm of encouraging people to purchase these labelled food products was low47. Although most studies found consumers had great interest or intention to buy antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use labelled food products31,32,42,47,48,50, one study performed in the UK suggested that only 32% of the participants reported they would prefer antibiotic-free products, while 50% of them were uncertain51. In addition, studies conducted in the US revealed that purchase frequency was low, with only a minority of consumers purchasing these labelled products often or exclusively33,57. However, a study conducted in Iran found more than half of participants often choose antibiotic-free chicken67. This might be due to the locale of the study (Guilan province), which is the largest producer of antibiotic free chicken in Iran. Another study undertaken in Iran revealed that only one third of participants purchased antibiotic free poultry meat in the year of investigation69.

Fifteen studies investigated consumers’ willingness to pay for antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use labelled food products. However, the research methods (e.g., choice experiments, questionnaires, and experimental auctions) and the findings varied significantly (see Supplementary Table 5). In general, most consumers were only willing to pay a small premium (e.g., <10% or 20% more than conventional products) for these labelled food products. In addition, compared to food products with reduced antibiotic use (e.g., without subtherapeutic use of antibiotics), consumers appeared to be willing to pay much more for products without any antibiotic use36,42. Moreover, consumers’ willingness to donate to non-profit organizations that seek to promote food products without subtherapeutic use of antibiotics was low, with an average donation of $ 0.04 per household per year61.

Studies also examined determinants of purchase intention/behaviour or willingness to pay for antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use labelled food products. A greater intention/likelihood to buy or higher willingness to pay was associated with higher awareness, positive perceptions (e.g. of higher quality and animal welfare standards), favourable attitudes, and purchase habits of the labelled food products31,32,37,42,47,58,67,69. In addition, greater exposure to advertisements, stronger social norms of purchasing labelled food products, and higher perceived behavioural control in finding and understanding antibiotic use information also led to an increased purchase intention/behaviour31,32,47,69. In addition, consumers who had higher risk perceptions of and lower acceptance of antibiotic use in food animals and antibiotic resistance, as well as higher concern about animal welfare expressed a higher intention to buy or willingness to pay for antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use labelled products31,32,37,47,58. However, higher price, lower availability, and purchase habit for conventional food products were linked to a lower intention/likelihood to buy or willingness to pay for the labelled food products31,32,58,69.

Two studies examined the effect of educational information on the willingness of US consumers to pay for food produced with different levels of antibiotics (i.e., with subtherapeutic use of antibiotics, without subtherapeutic use of antibiotics, and antibiotic-free)36,42. The results showed that information provision significantly increased participants’ willingness to pay for antibiotic-free food but not for food produced without subtherapeutic use of antibiotics36,42. Another study conducted in China also revealed that college students’ willingness to buy and willingness to pay more for antibiotic-free food products were significantly increased after exposure to information about the adverse effects of inappropriate antibiotic use in food animals on humans and the environment43. The participants also reported a higher support for antibiotic-free food labelling after information intervention43.

Consumers’ role in reducing antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals

Two qualitative studies discussed consumers’ perceived role in the food chain and in reducing antibiotic use in food animals and the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from animals to humans. Participants both in Ireland and Switzerland considered the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria an issue of collective responsibility, which is out of individuals’ control48,55. The participants felt that consumers are in a vulnerable position in the food chain and that it is the responsibility of farmers, food producers, and governments to ensure appropriate antibiotic use in food animals48,55. Participants in Ireland further argued that consumers should be more informed about antibiotic use in food animals. These participants believed that once consumers become aware and motivated, they could change their purchase behaviours, such as reducing the consumption of animal-derived food products, switching to, and paying more for products produced with reduced or no antibiotic usage. However, the participants believed that appropriate governance and antibiotic stewardship should be in place first48.

Demographics

Some demographic factors were associated with consumers’ knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes regarding antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals. In general, consumers who were female, older, married, highly educated, living in an urban area, or with higher incomes and full-time jobs seemed to be more knowledgeable, sceptical, and concerned about antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals32,37,41,45,52,56,60. They also had a higher intention to buy or willingness to pay for food products with antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use32,37,52,56,58,60,68,69,70. However, there were also some countervailing findings. For example, some studies found younger consumers were more knowledgeable and sceptical about antibiotic use in food animals50 and were more likely to purchase food products labelled with responsible antibiotic use42. An early study conducted in the US found consumers who were white, more highly educated, and with higher incomes were less concerned about meat produced with antibiotics at approved levels41. These inconsistencies might be due to the differences in measurements and participants’ social and cultural values.

Discussion

This review identified and synthesized 39 published research on consumers’ perspectives (i.e., knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes) on antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals. The publication years (Fig. 2) suggested that this is an emerging research interest in recent years. Through a thematical approach, we identified seven key themes from the included studies. The results indicated that existing literature has covered a broad range of topics relating to consumers’ perspectives on this subject. The following provides discussions of the key review findings.

Overall, this review found consumers lacked a deep understanding of antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals. Especially, substantial knowledge gaps emerged regarding how antibiotics are being used in livestock industries, the different purposes of antibiotic use (i.e., therapeutic VS. subtherapeutic use), what regulations are in place to restrict inappropriate antibiotic use, and the risks and pathways of antibiotic residues and antibiotic-resistant bacteria transmitting from animals to humans. The low understanding of these critical aspects of antibiotic use in food animals might have led to the lack of risk perception and the formation of misconceptions. On one hand, due to lack of knowledge about the health threats associated with antibiotic use in food animals, consumers had low risk perception of this issue. Consequently, they were more concerned about other food safety issues, such as genetically modified foods, food additives, and hormones41,54,55,56,57. On the other hand, because of low knowledge about different purposes of antibiotic use and antibiotic stewardship in food animals, consumers have formed some misunderstanding and misconceptions. For instance, some consumers believed that there are no regulations on antibiotic use in livestock industries and that antibiotic growth promoters are still legally allowed in countries where they have been banned. These knowledge gaps and misconceptions were largely due to a lack of communication and low information disclosure. Consumers especially thought information is scarce and untrustworthy, indicating that the lack of communication and transparency itself drives mistrust and concern.

Although consumers lacked a deep understanding of different purposes of antibiotic use in food animals, they did recognize the benefits of therapeutic use for animal welfare and food safety, as well as the risks of inappropriate use. Emerging evidence showed that consumers wanted antibiotic use in food animals to be reduced, but did not support a complete ban. Instead, consumers highlighted that livestock industries should take more preventive measures to reduce the need for antibiotic use, such as vaccination, good hygiene management, low stocking density, isolating sick animals from the herd, and regular veterinarian visits. These findings suggest that consumers have a strong demand for livestock industries to change farming practice and reduce reliance on antibiotics. To meet this consumer demand, firstly, governments need to strengthen regulations and monitoring procedures to ensure responsible antibiotic use in food animals. Although antibiotic growth promoters have been banned in many countries, there is a lack of regulation on the preventive use of antibiotics71. Given that farmers often administer large amount of antibiotics to their animals as a main approach to prevent diseases71,72,73,74,75, it is important to establish regulations to restrict such practice. For instance, the EU has banned the use of antibiotics as preventatives in animal feed and applying to entire herds10,65. In addition, governments need to establish monitoring systems to enforce the regulations considering that farmers often do not comply with established policies due to the lack of monitoring71,76,77,78. Second, the perceived risk of financial loss is a main barrier for farmers to reduce antibiotic use71,76,77,78. Therefore, governments and livestock industries need to implement incentive schemes and provide necessary training to assist farmers in making proactive changes.

Research has shown that consumers had positive perceptions of antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use labelled food products (i.e., being safer and healthier). However, the relatively high price and low availability hinder consumers from purchasing them. These findings are consistent with studies on organic food, which suggest insufficient availability and higher price are significant barriers for purchasing behaviours27,79. Due to these barriers, consumers showed high intention to buy antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use labelled food products, but the frequency of actual purchasing was low. Further, although most consumers were willing to pay more for the labelled food products, the premium they were willing to pay was rather small. In addition, compared with food products with reduced antibiotic use, consumers were willing to pay much more for products without any use of antibiotics. This consumer preference for antibiotic-free products seems to be contradictory to consumers’ support for necessary antibiotic use. That is, although recognizing the benefits of necessary antibiotic use and supporting this practice, consumers still prefer the absence of antibiotics in their food. As found in a Chilean study, most participants supported the use of antibiotics to treat sick animals, but they thought the animals should not be used for food production anymore after recovery40. This might be due to a lack of knowledge about antibiotic stewardship in food animals, especially regarding withdrawal periods40,57. These findings have important implications for future food labelling strategies regarding antibiotic use information. Currently, more and more “antibiotic-free” or “raised without antibiotics” labelled food products are emerging in the market in countries such as the US, Germany, the UK, Italy, and Australia31,34,80,81. These labels might mislead consumers to believe that unlabelled food products contain antibiotics and are not safe to consume. Moreover, increasing demand for these “antibiotic-free” products might incentivize the elimination of antibiotics from livestock industries, which will be harmful to both animal welfare and food safety82,83. Therefore, future food labelling initiatives should focus on promoting responsible antibiotic use rather than completely antibiotic free. Importantly, labelling initiatives need to provide reliable and detailed information on antibiotic use and the measures taken to prevent antibiotic residues and antibiotic-resistant bacteria presenting in food products (e.g., withdrawal periods), underpinned by a verifiable monitoring system32,48. This will assure consumers that antibiotics are being used responsibly and that the food products are safe to consume. In addition, given that limited availability and high price might prevent consumers from purchasing, future food labelling initiatives need to make labelled products more accessible and balance profitability for farmers and livestock industries with affordability for consumers.

This review suggested that consumers saw themselves in a vulnerable position in the food chain and believed there is little they can do to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use in food animals or to tackle antibiotic resistance. The sense of powerlessness might be due to the lack of public engagements and information disclosure, as consumers did not know how antibiotics are being used and what regulations are implemented to control antibiotic overuse. In addition, consumers placed the responsibility for inappropriate use of antibiotics and the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria on other parties in the food chain, such as farmers, food producers, and governments. Other-blaming was also found in veterinarians and farmers, who blamed increasing antibiotic resistance and inappropriate antibiotic use on other stakeholders, including other farmers and veterinarians, doctors and patients, and livestock industries77. These findings highlight a lack of accountability and self-efficacy among key stakeholders in tackling antibiotic resistance.

Several demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, education, income, employment, and living area) commonly appeared to be associated with consumers’ perspectives on antibiotic use in food animals. However, the findings were inconsistent across included studies, which is in line with the previous scoping review38. While these discrepancies could be due to the differences in research settings, methodologies, or participants’ social and cultural backgrounds, they also underscore the complexity of the subject.

Current research also identified gaps and scarcities in reviewed studies, which can provide directions for future research. First, most included studies did not specify and separate the purposes of antibiotic use in food animals (i.e., therapeutic and subtherapeutic use), which might have caused confusion among consumers, thus leading to unclear and conflicting findings. Future research needs to examine consumers’ perspectives on therapeutic and subtherapeutic use separately to avoid confusion and to gain deeper understanding on this topic. Second, most reviewed studies were conducted in developed countries. However, misuse and overuse of antibiotics in food animals is more common in developing countries11,13,21,22,23. Therefore, more studies need to be conducted to identify consumers’ perspectives in developing countries and draw direct comparisons between developed and developing countries. Third, most included studies used cross-sectional quantitative approaches without the adoption of established theoretical frameworks. More theory-based experimental, longitudinal, qualitative, interventional, and mixed methods research with improved methodologies need to be carried out.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review synthesizing consumers’ knowledge about, perceptions of, and attitudes towards antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals. We conducted a comprehensive literature search using well-defined selection criteria, followed by a systematic synthesis of the data, ensuring a rigorous and robust review process. However, this review has certain limitations. For example, it only includes peer-reviewed journal articles in English, which may have led to the exclusion of relevant research in other languages and in grey literature. Additionally, the included studies varied widely in settings, designs, sample characteristics, data collection and analysis methods, limiting our ability to conduct statistical synthesis of the findings or make comparisons across studies.

In summary, this study provided a comprehensive review of consumers’ perspectives on antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals and identified knowledge gaps. The review showed that the issue of inappropriate antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals has raised some concern among consumers in various countries, with consumers demanding for the reduction of antibiotic use and the reinforcement of legislations on antibiotic stewardship in food animals. However, consumers still lacked knowledge on some key aspects, including antibiotic use practice and antibiotic stewardship in food animals, the link between antibiotic use in food animals and increasing antibiotic resistance, and the transmission risks of antibiotic residues and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Although antibiotic stewardship is well established in livestock industries and by governments in many countries, it is still a “black box” to most consumers. This has led to the beliefs that consumers have no control over antibiotic use in food animals and that it’s the responsibility of other stakeholders (i.e., farmers, livestock industries, and governments) to ensure responsible antibiotic use. Lack of deep understanding of antibiotic use in food animals might have also led to the increasing demand for food produced without any use of antibiotics, which is problematic as eliminating antibiotics from therapeutic use is detrimental to both animal welfare and food safety. The review also showed that most consumers were willing to pay a small premium for antibiotic-free or reduced-antibiotic use food products, suggesting that using labelling schemes to disclose antibiotic use information is a promising strategy for quality differentiation. However, future food labelling initiatives should emphasize responsible antibiotic use instead of freedom from antibiotics.

Methods

Search strategy

This review was conducted and reported in line with guidelines on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)84. We searched the literature for records published up to December 31, 2023. A librarian specialized in biosecurity (D.J.) conducted the literature search in four databases: PubMed, Web of Science (Web of Knowledge Core Collection), Scopus, and Google Scholar. The initial search was performed on November 14, 2022. An updated search was carried out on April 30, 2024, and integrated with the original search result, extending the timespan to December 31, 2023. The search terms were derived from “consumer/public”, “knowledge/perception/attitude/behaviour/intention”, “antibiotic/antimicrobial” and “food animals/livestock/agriculture/aquaculture”. The combinations of these terms were used. Full details of the search strategy for each database are presented in Supplementary Table 6. In addition, we conducted forward and backward citation searching for all included articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The eligible criteria for this review were: (1) Focusing on knowledge/perception/attitude/behaviour/intention regarding antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals; (2) Participants of any age from general public/consumers; (3) Written in English; (4) Full-text articles and original research; (5) Peer-reviewed journal articles; (6) Published up to December 31, 2023. We put no limits on study design and study context. Studies were excluded if they focused on other aspects such as food safety, food labels, animal welfare, natural/organic food, sustainable food, general attributes of food products, food production technologies, and farming system.

Screening and selection

The search results were extracted into Endnote 20 and checked for duplicates. One team member (Y.Z.) then screened all the titles and abstracts retained from literature search for relevance, while another researcher (D.J.) randomly screened 25% of them. Uncertainties and discrepancies were discussed and resolved by Y.Z. and D.J. Following this step, Y.Z. assessed full-text articles against inclusion criteria for eligibility. Uncertainties around the inclusion of articles were resolved via discussion by Y.Z. and A.Z. The full process of searching, screening, and selecting publications for both original and updated searches is illustrated by the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Quality assessment

The quality of all included articles was assessed using “The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018”85. The MMAT is developed for the quality assessment of systematic review of mixed studies. It appraises the quality of methodology for five types of study designs: qualitative study, randomized controlled study, nonrandomized study, quantitative descriptive study, and mixed methods study. The appraisal checklist includes 2 screening questions for all studies and 5 criteria for each type of study design. For each included study, screening questions and the criteria of specific study design were applied to assess the methodological quality. The assessment was conducted by one researcher (Y.Z.) and verified by another (A.Z.).

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction and synthesis was carried out by Y.Z. and verified by A.Z. and R.D.v.K. Three sets of data were extracted: (1) characteristics of studies, including author, year of publication, country, objective, study design, population, sample size, and response rate; (2) characteristics of participants, such as age and gender; and (3) outcomes related to research question. Collected data on characteristics of studies and participants were tabulated and visually displayed in figures. Extracted data regarding consumers’ knowledge about, perceptions of, and attitudes towards antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food animals were synthetized using a thematical approach. The data were coded and grouped into potential themes, which were further defined and refined. Seven key themes emerged from this synthesizing process.

Responses