Continental-scale shellfish reef restoration in Australia

Introduction

Target 2 of the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework has raised ambitions for the restoration of degraded ecosystems. The target commits countries to ‘ensure that by 2030 at least 30% of areas of degraded terrestrial, inland water, and coastal and marine ecosystems are under effective restoration’ by 20301, and doubles the target of 15% from the previous decade2. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has also clearly identified the role of habitat restoration, when implemented at scale, as a key adaptation solution for reducing climate change impacts on coastal and marine ecosystems3, while the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) further recognises the intrinsic linkages between such climate adaptation solutions and climate mitigation4.

Restoration of marine and coastal habitats faces multiple challenges including development of effective, scalable restoration methods and integration of social and ecological restoration priorities5,6. Documenting examples of large-scale restoration of marine ecosystems, and the factors both enabling and inhibiting restoration outcomes, is critical for learning and adaptation. Here we document planning and progress to restore temperate shellfish reefs, in 30% of their former distribution in Australia. Shellfish reefs are structural features in coastal waters created through the aggregation and accumulation of bivalve molluscs, such as oysters and mussels.

Why do shellfish reefs need restoring in Australia? The first continental-scale assessment of shellfish reefs found “dramatic decline in the extent and condition of Australia’s two most common shellfish reef ecosystems, developed by Sydney Rock Oysters Saccostrea glomerata and Australian Flat Oysters Ostrea angasi”7. The decline occurred during the “mid-1800s to early 1900s in concurrence with extensive harvesting for food and lime production, ecosystem modification, disease outbreaks and a decline in water quality”7. Prior to the mid-2010s, knowledge on the extent, physical characteristics, biodiversity and ecosystem services of Australian shellfish ecosystems was extremely limited7. Shellfish reefs, including oyster reefs, provide both structured habitat and add food to that structure in the form of biodeposits as the byproduct of filtration. Consequently, these habitats provide outsized biodiversity benefits8, fish production9 and nutrient mitigation10 as well as sediment stabilization shoreline protection and the associated jobs and economic support11. This makes them a small natural feature that has ecological importance that is disproportionate to their size12.

The degradation of southern Australia’s shellfish reefs, and that of their once supporting coastal and estuarine environments, has been assessed in a variety of ways across both national and local scales over the past decade. Nationally, this included a science-led approach to systematically review the current status and historical extent of reef-forming shellfish across Australia7. The study assessed the conservation status and risk of ecosystem collapse for the Oyster Reef Ecosystem of Southern and Eastern Australia in alignment with the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems risk assessment process13, and ranked the ecosystem as Critically Endangered with a high degree of confidence. Since 2014, national understanding of shellfish reef degradation has also developed from several studies exploring the historical socio-ecology of shellfish reef exploitation14,15,16, convening face-to-face workshops, meetings and conferences with relevant research, conservation and management agencies, and developing a national community of practice (e.g. Australian Shellfish Reef Restoration Network).

Ecoscape-scale restoration of shellfish reefs

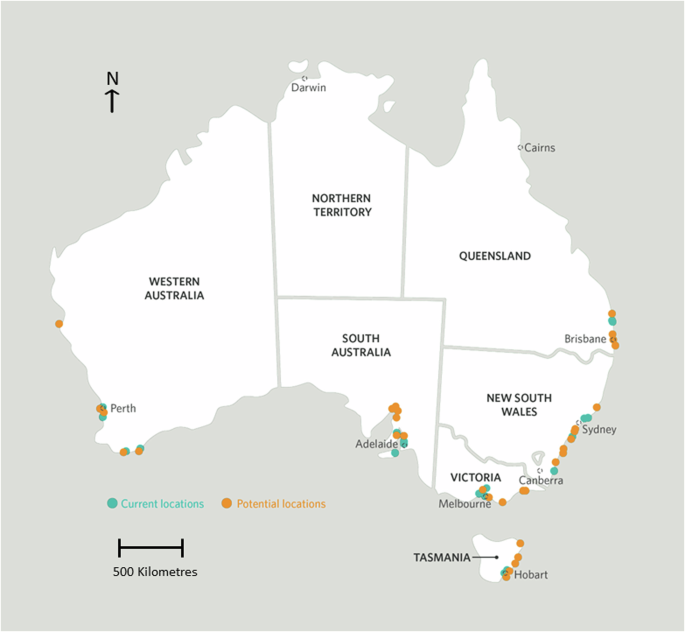

Over the last decade, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), a non-government conservation organisation, has been working in partnership with Australian policy-makers, regulators, natural resource managers, First Nations communities, researchers, recreational fishers and environmental groups—spanning national to local scales—to galvanise support, build expertise and lead action in the large-scale restoration of Australia’s shellfish reefs7,13,17,18,19. The goal has been to restore oyster reefs to 30% of the bays and estuaries that were once dominated by oyster reef habitat. That equates to the restoration of 60 reef systems, an accomplishment that would trigger a reassessment of the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems status to a lower threat category for the Oyster Reef Ecosystem of Southern and Eastern Australia. As of April 2024, TNC has led the restoration of 21 shellfish reefs (Fig. 1) covering 62 hectares, demonstrating that these vital habitats can be recovered at meaningful scales and reversing the trajectory towards extinction. This restoration has often been undertaken to improve the health of bays and estuaries in conjunction with or parallel to other restoration efforts focusing on marine (e.g. seagrass), tidal fringe (e.g. mangroves and saltmarsh) or riparian ecosystems. These combined ecoscape-scale restoration efforts can achieve additional benefits from reductions in nutrients, sediments, and other water quality improvements, than any single restoration method alone. Some integral elements of building and progressing this ecoscape-scale restoration program are outlined below (and Fig. 2 presents more detail in a flow diagram).

Prospective restoration locations will be subject to further refinement through further feasibility and stakeholder engagement assessments.

Stages of shellfish reef restoration, from project pre-planning through to project handover.

Building trust, knowledge sharing and restoration capacity

The shellfish restoration approach adopted in Australia relies on multisectoral partnerships to build the evidence base (e.g. science, traditional knowledge, expert opinion, local stories, pilot trials), canvas wide perspectives and build the practical expertise (internally and with delivery partners) to deliver large-scale shellfish reef projects. This has included supporting national networks of coastal restoration practitioners (e.g. Australian Coastal Restoration Network) to promote knowledge sharing and, more recently, providing a close supporting role for local natural resource management agencies to enable them to lead the on-ground delivery of large-scale reef restoration projects. TNC’s extensive history of successful oyster reef restoration in the USA20 provided confidence to governments and stakeholder groups to enable early trials of the restoration approach in Australia21.

Demonstration of national-scale on-ground experience and success

The multisectoral partnership has now restored multi-hectare shellfish reefs in all six states across southern and eastern Australia (Figs. 1, and 3), and often at multiple local geographies per state. This has required not only building the requisite partnerships in each geography to garner supporting evidence, expertise and trust, but also navigating nationally disparate and complex legislative frameworks, permits and approvals for (i) implementing marine construction projects at this scale; (ii) ensuring environmental and public benefit as opposed to harm, and (iii) ensuring the reef structures remain in situ in perpetuity and under appropriate environmental management by state-based agencies22,23. This widespread experience, combined with ongoing advocacy for streamlining legislative frameworks, was fundamental for enabling shellfish reef restoration at this scale.

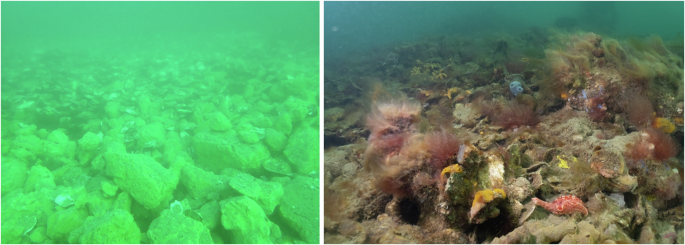

Image (left) of shellfish reef post construction with limestone rock base and seeded with oyster spat on recycled shell, Wilson Spit, Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, 2017. Photo: Simon Branigan/TNC. Image (right) of the same reef in 2023, with high survival and growth of Australian Flat Oysters and colonised by red seaweeds, temperate sponges and nudibranch in the foreground. Photo: Jarrod Boord, Streamline Media

Influencing coastal restoration policy and legislative frameworks

Oyster reef ecosystems were nominated to be assessed as a threatened ecological community under Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 based on peer reviewed evidence of the historical loss of shellfish reefs7,13. If listed as a threatened ecological community, this will raise considerable awareness about the loss and need to further recover shellfish reefs and potentially lead to a recovery plan. In addition, several papers identifying solutions to current challenges regarding the permitting framework for marine ecosystem restoration in Australia have been published to target policy changes18,22,24.

Financing mechanisms and future sustainability

Since 2014, TNC has secured ~AUD$40 million (USD$26 million) in funding from a range of government, industry and philanthropic sources to support the shellfish reef restoration. Within governments, this funding has come variously from environment, fisheries and regional development departments, highlighting the multiple values of these ecosystems.

From 2019, the case for funding a national-scale restoration program was proposed to the Australian Government, based largely on the Critically Endangered status of the ecosystem. Following the extensive Black Summer wildfires in Australia in 2019–2020, the case was made that a national restoration program could help recover degraded estuaries from ash deposits and to stimulate local economies. In October 2020, the Australian Government announced a commitment to provide AUD$20 million towards creating local employment opportunities to assist communities recover from the dual effects of COVID-19 and bushfires whilst restoring shellfish habitats25. Influencing this was data on job creation in Australia from shellfish reef restoration projects, but also from the USA, where shellfish reef restoration is a significant economy of its own, providing substantial economic contribution and job creation26.

Securing the requisite funding to fully realise the goal of this ecoscape-scale restoration by 2030 will require support from additional and more consistent sources. There are a number of emerging market-based opportunities to attract greater private investment to reef restoration alongside traditional funding sources, including development of ‘methods’ for shellfish reef restoration (or broader coastal ecosystem restoration) under emerging biodiversity credits markets. TNC has further been exploring the feasibility of other innovative financing mechanisms, including blue impact bonds (investment frameworks for coastal restoration projects that yield financial returns while generating positive environmental benefits), blue insurance products (reduced insurance premiums for coastal infrastructure as a result of reducing risk to coastal hazards through restoring key habitats), and seafood enterprises with a proportion of proceeds cycling back to restoration projects. Further expansion of the partner-delivery model identified will also assist with reducing upfront costs and mobilising partner in-kind contributions into on-ground delivery.

Major challenges and lessons learnt

There were a number of major challenges that were commonly encountered in restoring shellfish reefs. A key stage of any restoration project is securing the relevant local and state government permits and approvals during the planning and permitting stage. The approval pathway differs between Australian jurisdictions and was sometimes unclear22, however, a common element is the requirement for a development application approval. In many jurisdictions, shellfish reef restoration is considered the same as building grey infrastructure such as bridges and the approval timeframe for development applications, combined with other permit obligations, took more than a year. This had flow on effects for other logistics such as contractor procurement and seasonal timing of deployment. Permit conditions also vary by jurisdiction, but a common negotiation area is the liability conditions, particularly for ownership of, and responsibility for, maintenance of the reefs. The tenure of the seabed where shellfish reefs are restored is under government jurisdiction, so ensuring that TNC was not liable for the reefs in perpetuity was a priority.

Two other challenges in relation to the logistics of in-water restoration at scale are (1) locating suitable load-out sites and (2) sourcing juvenile oysters to seed the reefs with. Load-out sites are the land-based areas where rock (used to construct reef bases) and/or shells are transported, stockpiled, then loaded onto a barge to be towed out by a tug to undertake reef base construction (Fig. 4). Locating a suitable load-out site was difficult in both busy urban estuaries and in rural areas and required consultation with local government, maritime authorities and the community. The site needed to allow for regular truck movement, a large quantity of reef base materials to be stored, a water depth suitable for a barge to berth, and ideally, rock revetment on the shoreline. Another major logistic consideration is the proximity of restoration locations to a shellfish hatchery. Most restoration locations were recruitment limited, meaning that the new reefs needed to be seeded with juvenile oysters to kickstart the recovery process. For locations geographically distant from hatcheries, remote setting methods were applied for the first time in Australia. Oysters were reared to the free-swimming larval stage in a hatchery, then cooled to allow transport to a temporary shoreside setting facility near the restoration location. Local shellfish farmers were integral in this remote setting process through providing tanks and other infrastructure to settle the larvae on recycled shells, husbandry advice and seeding of the grown-out spat on shell on the nearby reefs. The remote setting approach was proven to be successful and relatively inexpensive, however was a labour-intensive activity for a 2–3 week period in terms of the time commitment and having expertise in hatchery operations and oyster husbandry knowledge is an advantage.

Upper image: Longreach excavator loading locally sourced andesite rock onto barge at a load-out site adjacent to Sydney Airport, Botany Bay, New South Wales, 2023. Photo: Kirk Dahle/TNC. Lower image: Shellfish reef construction using a barge, longreach excavator and locally sourced limestone rock, Nyerimilang, Gippsland Lakes, Victoria, 2022. Photo: Scott Breschkin/TNC.

More local challenges included selecting suitable restoration locations in busy, urbanised estuaries that stakeholders supported, procuring marine construction contractors with the infrastructure and necessary skill set to undertake ecological restoration and the flexibility to delay works until permits were secured and project funding timeframes that allow for follow-up monitoring at least 6 months post restoration.

Future directions

Building on the momentum and learnings from the 21 shellfish reefs restored to date, focus is now set on restoring a further 39 reefs across Australia by 2030, thus achieving the 30% restoration target for this ecosystem. Prospective locations for the remaining 39 reefs have been mapped (Fig. 1) and will be refined with local partners and stakeholders as projects progress towards implementation.

In addition to further progressing key enabling conditions identified above (e.g. sustainable financing and supportive policy and legislation) and adapting restoration strategies based on lessons learnt, areas for expansion during the next phase of restoration towards 2030 include:

-

1.

Building the capacity of local delivery partners through (i) co-design of new reefs with stakeholders, (ii) two-way knowledge and skills transfer to lead reef construction projects, and (iii) expanding on-ground volunteer opportunities.

-

2.

Expanding opportunities to restore shellfish reefs alongside other native coastal habitats (e.g. seagrass beds and kelp forests) to further amplify ecological connectivity and ecosystem benefits and accelerate wider coastal ecosystem resilience. This includes both opportunities for active co-restoration, as well as adapting reef design to better facilitate natural recovery of surrounding habitats. Several of the restored reef locations are already demonstrating positive results, including through the natural return of seagrass meadows and mangroves where they were historically lost. For example, monitoring has recorded up to 320 seagrass seedlings/m2 in the lee of restored reefs in South Australia27, reflecting similar outcomes in other countries28.

Documenting the enabling factors and challenges to large-scale restoration programs will be critical to advance Target 2 of the Global Biodiversity Framework29, in addition to better clarifying interpretation of that target30. Many of the lessons for shellfish reef restoration in Australia have relevance for (a) oyster restoration in other countries, (b) restoration of marine ecosystems and (c) large-scale ecosystem restoration generally.

Responses