Could transparent model cards with layered accessible information drive trust and safety in health AI?

Medicines and medical device labelling in comparison to the Model Card

For medical devices, including AI models, laws specify many requirements for the IFU but do not standardize the layout of this information. Although these documents provide much useful information, they do not standardize the layout of capabilities, limitations, safety, performance, validation, or on other parameters as the Model Card does. Patients wanting to know about the suitability of a medical AI, doctors prescribing medical AI, or health system buyers and information system implementation engineers looking to locally implement AI tools in their hospitals would find it hard to extract information for side-by-side comparison from current IFUs.

In the US, UK and EU, there is already a legal requirement for a standardized compulsory medical device label (and therefore, by extension, an AI Model when these are used for a medical purpose). However, this provides highly technical information such as lot and serial numbers, the names of assessing certifying bodies (Notified Bodies) and importers (Fig. 2). It does not provide the tangible information a patient is likely to want, or the information critical to know for AI system introduction and implementation.

This is an example EU label, which uses the standard symbols legally required for use from ISO 15223-1:202117 and is very similar to international labels required under medical device law (see ref. 18 for a similar US example).

We agree that the more standard layout of information for users in the Model Card, with which they could quickly become familiar, would likely assist them in comparing different AI models. The Model Card proposed by CHAI1 (Fig. 1), does not include all the information required on a medical device label (Fig. 2), but these two concepts could be provided together or merged, with the latter approach being superior as avoiding repeated data.

Accessibility and comprehensibility for different users

AI development and validation uses a vast array of technical jargon, much of which is not readily understandable to the layperson, or even to health care providers (HCPs) unless they have had advanced technical training4,5. An AI label is of little practical use if it conveys information but does not truly communicate understanding. For many patients, and some HCPs, the information in both the proposed Model Card and the medical device label will be minimally comprehensible. Arguably neither approach has been developed with these user groups to the forefront. Is it important that labelling and product information is comprehensible to patients? It is required that IFUs undergo usability testing, where the ability of users (including patient users, if applicable) to follow critical instructions is assessed3. Explaining technical information in an accessible manner to users and the public relies upon simplicity and uniformity. We advocate for much greater standardization of information supplied to users, with the presentation of this information in highly usable formats, that look the same for every product and use standardized layouts for including, ordering and ranking of information. When users are faced with highly detailed information that has a format that differs for every new product that they encounter, this can lead to information overlap and disengagement, irrespective of how much effort has been taken to present information well. The CHAI Model Card delivers a highly standardized format, but interestingly it is entirely text-based, with simple titles in repeated tabular elements1. Under headings, it provides boxes for text-based model descriptions, but it is unclear how long these responses can be and stipulates links should be provided to the validation process and its justification.

Other authors have proposed graphical approaches to provide information to consumers, including for AI, based on food nutritional quality labelling, food origin labelling and energy efficiency labelling6,7,8 (Fig. 3). These approaches focus on the labelling of the ethics of AI models, but the domains described overlap the CHAI model card (e.g.6,7,8, and1 both address the domains of fairness and equity). Consumers are used to simple coloured rating scales, which rapidly convey complex information that allows consumers to make fast decisions. Is this approach applicable to AI in the health domain? If such approaches were to be used to convey critical safety information for users, they may not be applicable, and they should not be used as a substitute to inherent safe design. They may however be applicable to convey information about the ethical sourcing of data for model training, ethical employment practices in model training, and responsible approaches to data privacy, antidiscrimination, and intellectual property.

It has been recognized in food labelling and energy-efficient labelling that communication is best done through highly standardized and easy-to-interpret color scales and simple ratings. Similar approaches have been proposed for AI ethics labels6,7,8.

Layered verifiable information to avoid the label serving as a conduit for false claims

The AI Model Card has the beauty of simplicity, but beauty is not skin deep. In order to be both useful and safe, it is critical that the Model Card (and if used, the ‘Nutrition Label’ for patients) is linked to verifiable and refreshed data on model safety and performance. Any label or Model Card is only as good as the verifiable deeper meaning of the information it summarizes.

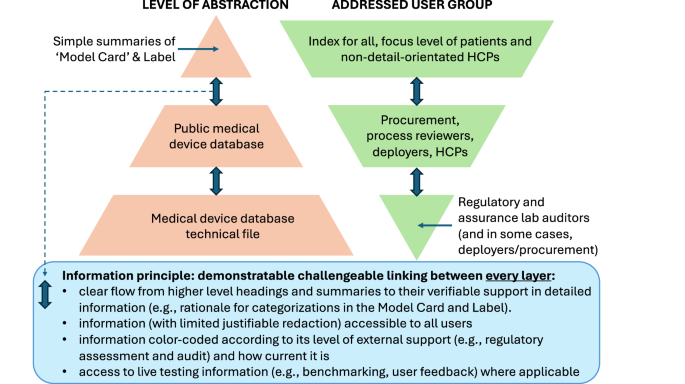

The CHAI ‘Model Card’ already has a degree of information layering through the way in which it orders information, starting from goals to results, then to methods, followed by links to external sources for justifications and more detailed methods descriptions. The layering of information, starting from higher level principles, with successive linking through to more complex and detailed information, is a longstanding approach for structuring information, increasingly used in digital information tools, e.g. in wikis. As we set out above, layered information serves two primary purposes (Fig. 4). Firstly, it allows the high-level summaries to be simple and accessible to many users (including some patients and non-tech-savvy HCPs), while allowing the more curious user, depending on the detail they need, to look at successively deeper layers of information. This serves the second purpose, which is to have the credibility of information checked by users, who can at least to some degree verify the compatibility of links between summaries and data. This should be assisted by appropriate mechanisms to allow reporting of problems9.

Patients and non-detail-oriented HCPs can access simple information, but this must always be linked and cross-verifiable with lower-level information and open external test/benchmarking data to avoid Model Cards being corrupted from a force for genuine transparency to a vehicle for misleading marketing claims.

Is an accessible layered ‘Model Card’ applicable to general-purpose AI

There is increasing development and direct and indirect use of general-purpose AI (GPAI) models in health and these models challenge the approaches that were developed for the oversight and regulation of specifically developed (and generally narrow scope) AI-enabled medical devices10,11. The EU AI Act sets out a series of requirements for GPAI providers12,13. The developer of the GPAI models must make a large amount of information available to the downstream providers of AI systems. When developers of a GPAI model directly apply the system in health or make it available for medical purposes then they become providers of high-risk AI systems. The delivery of meaningful transparency and the exchange of useful information between GPAI developers and downstream medical device ‘manufacturers’ calls for common approaches on transparency and model testing, which are best delivered through standardized approaches14,15. This raises the question, should Model Cards be applicable only to downstream medical device products (e.g., approved clinical decision support systems) that have defined (even when broad) intended purposes and target populations and clinical indications, or should Model Cards also be applied for underlying GPAI models, where these are intended to be the foundations of later approved medical device products? In other words, could Model Cards be used to describe the basic claims made by providers of GPAI models? Downstream providers of healthcare AI systems must receive an extensive range of information from GPAI providers, so that they can satisfy the information requirements of the AI Act, and where needed, pass this information on to deployers and users. The high-level Model Card does not directly include all this information, but as described in Fig. 4, the concept could readily be linked to this information, serving as a starting point, or a form of directory for more detailed model information. Once GPAI models providers make a Model Card available for their GPAI, would these models then be used directly by HCPs and patients (even where the Model Cards and laws state that they should not), bypassing developed, fine-tuned and approved downstream medical device products? This is likely to occur to a degree if these models are available to downstream users11 and it will require strong engagement with users and strict enforcement action if regulators aim to stop it.

Balancing transparency with practical implementation

The CHAI Model Card summarizes this critical model information through a standardized table. Do we propose changing the simple Model Card into a ‘bureaucratic monster’?

We argue that the utility of the ‘Model Card’ in the hands of its users must be measured through representative quantitative and qualitative assessment, accounting for cultural and international differences. As far as we can determine, the ‘Model Card’ has not been systematically tested, and this should be done before widespread uptake. It is also important that the approach gains regulatory acceptance, otherwise it is difficult to see it being sustainable.

A yet harder challenge is ensuring that the information provided in the card is reliable and genuinely transparent. If not well audited, the Model Card could turn out to be highly accessible to users, but with underlying information that is predominantly deceptive marketing spin rather than truly reliable transparent information. This is a clear and present danger for AI nutrition labels and Model Cards that must be avoided to maintain public safety and to avoid the erosion of public trust in health AI. This is not scaremongering – in September 2024 a US Attorney General investigation was settled after a company deployed a GPAI medical documentation and summarization tool at several Texas hospitals after making a series of false and misleading statements about the accuracy and safety of its products16. The ‘Model Card’ could either be a system that serves safety and the ethical use of AI, or it could turn into a charade, with companies in a race to the bottom of true transparency and top of claimed performance, as each takes steps to outdo the last based on percentages massaged for the better marketing messages but unsupported by any rigorous data or by any independent audit under the eyes of regulators or the public. Health AI needs innovative concepts like the CHAI Model Card, and even graphical ‘nutrition labels’ for patients, but it also deserves to have these well-validated, integrated with regulatory labelling, and most importantly, containing verified auditable and open information.

Responses